Abstract

To aid primary care providers in identifying people at increased risk for cognitive decline, we explored the relative importance of health and demographic variables in detecting potential cognitive impairment using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Participants were 94 older African Americans coming to see their primary care physicians for reasons other than cognitive complaints. Education was strongly associated with cognitive functioning. Among those with at least 9 years of education, patients with more vascular risk factors were at greater risk for mild cognitive impairment. For patients with fewer than 9 years of education, those with fewer prescribed medications were at increased risk for dementia. These results suggest that in addition to the MMSE, primary care physicians can make use of patients’ health information to improve identification of patients at increased risk for cognitive impairment. With improved identification, physicians can implement strategies to mitigate the progression and impact of cognitive difficulties.

Keywords: mild cognitive decline, MMSE, cognitive impairment

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is increasingly recognized to be associated with an elevated risk of dementia, especially Alzheimer’s disease (AD; Farias, Mungas, Reed, Harvey, & DeCarli, 2009; Unverzagt et al., 2007). A patient meets the diagnostic criteria for MCI if he or she meets the following: a subjective cognitive complaint (by the patient or an informant), impaired cognitive functioning that is not normative among similar-aged individuals, no diagnosis of dementia, and otherwise normal functioning activities (Petersen, 2004). MCI is estimated to affect approximately 14% to 18% of people 70 years and older (Petersen et al., 2009). The impact of MCI on older adults may be even more substantial among older African Americans, who are disproportionately affected by MCI. A number of community-based studies in the United States have shown that the prevalence rates of MCI and AD are higher among African Americans than non-Hispanic Whites (Demirovic et al., 2003; Heyman et al., 1991; Husaini et al., 2003). An epidemiological study showed that nearly one in four community-dwelling elderly African Americans is affected by MCI, and that the prevalence increases with advancing age (Unverzagt et al., 2001).

The disproportionate rates of cognitive impairment among African American elders may be attributable to higher rates of comorbid health issues, such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity (Baker, 1992; Mehta et al., 2004), and differences in the quantity and quality of education (Albert & Teresi, 1999; Manly, Jacobs, Touradji, Small, & Stern, 2002; Manly, Touradji, Tang, & Stern, 2003; Shadlen et al., 2006). Others have suggested that the elevated prevalence rates of MCI among African American elders may also be due to lower income and disparities in access to medical care among African Americans (Husaini et al., 2003; Mehta et al., 2004).

A recent review found that ethnic minority elders (non-English speaking/non-Australian born, non-European Americans) were more likely to access diagnostic services at later stages of dementia, when they are more cognitively impaired, than nonethnic minority elders (Cooper, Tandy, Balamurali, & Livingston, 2010). Others have suggested that African Americans delay seeking medical attention because of different expectations of changes in cognitive function associated with normal aging (Chin, Negash, & Hamilton, 2011). African Americans were more likely than Whites to attribute substantial memory loss as a normal aspect of aging (Connell, Scott Roberts, McLaughlin, & Akinleye, 2009); therefore, individuals experiencing minor cognitive difficulties may be less likely to seek treatment. Cultural differences have also been found in caregivers’ perceptions of their care recipient’s cognitive functioning (Burns, Nichols, Graney, Martindale-Adams, & Lummus, 2006; Potter et al., 2009).

Due to the disproportionate rates of cognitive impairment among older African Americans (Demirovic et al., 2003; Heyman et al., 1991; Husaini et al., 2003; Unverzagt et al., 2001), dementia was likely to be seen as normal aging among African Americans than among non-Hispanic Whites (Demirovic et al., 2003). Furthermore, minorities were less likely to seek medical attention for AD, compared with non-Hispanic Whites (Barnes & Bennett, 2014). Individuals with memory problems did not recognize signs of cognitive decline, thus failed to seek help for memory difficulties (Wilkins et al., 2007). Difficulties associated with undiagnosed cognitive impairment may extend beyond memory problems to everyday functioning. For example, older individuals with memory deficits were less likely to adhere to their medication regimens (Cooper et al., 2005; Hayes, Larimer, Adami, & Kaye, 2009), which may have contributed to a downward spiral of poor health management, increased complications of comorbid diseases, and higher health care costs. Among patients with dementia, health care costs were much higher for African Americans than Caucasians, partly due to increased use of inpatient and emergency services (Husaini et al., 2003).

Considering that African American elders are less likely to seek medical attention for memory problems, it is important for their primary care physicians to recognize signs of cognitive decline among this vulnerable population. Attention to patients’ cognitive abilities and risk factors associated with cognitive decline by primary care doctors could aid the early detection of cognitive impairment and initiate appropriate treatments to help manage reversible causes of dementia (Wilkins et al., 2007), with referral to specialists when applicable. By being more cognizant of patients’ declining cognitive abilities, physicians could initiate strategies to improve medical adherence, leading to improved overall health outcomes.

Developed to be easily administered in a timely manner, the Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) is often used to screen for patients with cognitive deficits suggestive of dementia. However, there are concerns regarding whether MMSE scores could identify MCI patients at increased risk dementia (Arevalo-Rodriguez et al., 2015). The MMSE has been found to have low specificity in screening for cognitive deficits among African Americans versus Whites (Fillenbaum, Heyman, Williams, Prosnitz, & Burchett, 1990; Stephenson, 2001), and culture bias has been reported (Tappen, Rosselli, & Engstrom, 2012). Although demographically adjusted MMSE scores have been proposed for African Americans, the use of adjusted MMSE cutoff scores provided only modest improvement over unadjusted cutoff scores (Pedraza et al., 2012). Although the MMSE is not an ideal measure to detect impairment among African American, it remains widely used and therefore it may be useful to better understand the utility of MMSE among African American elders.

Previous studies have examined the extent to which age and education influence MMSE performance among older African Americans (Marcopulos & McLain, 2003; Marcopulos, McLain, & Giuliano, 1997). After controlling for age and education level, African American elders with diabetes were reported to have worse performance than those without diabetes, whereas no association was found for hypertension (Hawkins, Cromer, Piotrowski, & Pearlson, 2011). These findings suggest that MMSE performance of older African Americans may be influenced by demographic (e.g., age, education) and health variables (e.g., chronic illness, number of medications).

In most of the previous studies, multiple regression models were used. Although multiple regression models allow researchers to delineate the independent effects of certain variables on the outcome variable (e.g., the effect of diabetes on MMSE, after controlling for age and education), it is difficult to interpret results from multiple regression models for clinical applications (Lemsky, Smith, Malec, & Ivnik, 1996). Beta (β) weights derived from multiple regression models may have limited use in clinical practice for primary care physicians conducting assessment of patients’ cognitive status. Considering that primary care physicians may have difficulty in identifying patients with MCI (Mitchell, Meader, & Pentzek, 2011), a set of decision rules which can be easily implemented in clinical practice using demographic and health variables to identify individuals at higher risk for cognitive impairment, may be particularly helpful for clinical application.

The goals of the current study have real-life clinical applicability and are threefold. First, we aimed to examine cognitive functioning, as measured by the MMSE, of older African Americans with no prior cognitive or memory deficits visiting their primary care physicians for nonmemory-related reasons. Second, to better understand factors that may affect patients’ cognitive performance on the MMSE, we investigated how patients’ demographic and health characteristics (e.g., number of medications, vascular risk factors) are associated with their cognitive performance. We hypothesized that cognitive performance would be negatively associated with age, participants with higher education levels were expected to have better cognitive performance than those with lower education levels, and patients with poorer health were expected to show worse cognitive functioning than those who were healthier. Finally, we explored which of the demographic and health variables were the most relevant in identifying patients with concerns for cognitive impairment using classification tree modeling.

Classification tree modeling was used to develop a set of decision rules to estimate patients’ cognitive status based on their demographic and health characteristics. Advantages of classification tree models include allowing the simultaneous exploration of linear and nonlinear associations between the independent and dependent variables, as well as all possible interactions among independent variables. Furthermore, results from the classification tree analyses are easy to interpret, and may be directly applied in clinical practice.

Method

Participants

Participants were African American adults 60 years or older who were visiting their primary care physicians for routine visits at an academic medical center primary care clinic. None of the participants were being seen for cognitive complaints and none reported any memory problems to their primary care physicians at the current or prior visits. None of the patients had been previously diagnosed with dementia, MCI, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression per their medical records. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Virginia and followed procedures in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants gave written informed consent. Participants were recruited at visits to the primary care clinic. The study was designed to have minimal impact and time demands on the participants. Immediately following the visit with their primary care physician, participants were administered a cognitive screening including the MMSE, filled out demographic questionnaires, and gave permission for access to their medical records for additional medical information.

Demographic variables of interest included age, gender, and education. Patients’ medical records were reviewed.1 Health variables recorded for this study included the number of medications prescribed and vascular risk factors as documented in the patients’ medical records. Vascular risk factors obtained from the medical records included smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, and history of stroke. Smoking referred to current smokers and/or those who had quit smoking within the last 10 years. Hypertension referred to patients with documented diagnosis according to the ICD9 (International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision) code for stroke, and with prescribed hypertension medication. Diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia were ascertained with the diagnoses indicated in the patients’ medical records, and stroke was defined with the ICD9 code for stroke, including ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Body mass index (BMI) was computed by dividing weight (kg) by height2 (m2), and obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 30, as per the World Health Organization’s classification.

A total of 96 African American patients participated in this study. After removing two patients with 30 or more prescribed medications,2 who represented clear outliers, the remaining 94 (36 men, 58 women) patients were included in the subsequent analyses. Demographic characteristics of the patients and prevalence of vascular risk factors in this sample are shown in Table 1. Patients were categorized into three groups of varying cognitive functioning: normal (MMSE > 26), concerns for MCI (MMSE ≤ 26; Folstein et al., 1975), and concerns for dementia (MMSE ≤ 20; as cited in Wood, Giuliano, Bignell, & Pritham, 2006). Considering the poor specificity of MMSE for African Americans (Fillenbaum et al., 1990; Stephenson, 2001), we opted for a conservative cutoff score for dementia (MMSE ≤ 20) to include only patients with the most severe cognitive impairment.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants in the Current Study.

| Demographics | Total (N = 94) | Men (n = 36) | Women (n = 58) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | 69.18 (6.8) [60–92] | 69.92 (7.04) [60–92] | 68.72 (6.66) [60–83] |

| Educationb | 10.5 (3.16) | 9.89 (3.89) | 10.88 (2.57) |

| No. medicationsc | 10 [0–22] | 9.5 [0–21] | 10.5 [0–22] |

| No. vascular risk factorsc | 3 [0–4] | 2 [0–4] | 3 [1–4] |

Note. No statistically significant differences between genders. No. medications: Number of medications documented in medical records. No. vascular risk factors: The total number of vascular risk factors.

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean (standard deviation) [range].

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean (standard deviation).

Descriptive statistics are presented as median [range].

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.2.1 (R Development Core Team, 2015). First, we examined the prevalence of vascular risk factors in this study sample. Each vascular risk factor was treated as a dichotomous variable; a value of 1 was given if present and a value of 0 if absent. Vascular risk factors were treated as dichotomous variables to examine the cumulative effects of multiple risk factors on cognitive functioning. The total number of vascular risk factors was computed by summing the vascular risk factors present for each participant; the total possible number of vascular risk factors could range from 0 (no vascular risk factor present) to 6 (all vascular risk factors present). We examined the associations between patients’ demographic and health characteristics (i.e., number of medications and vascular risk factors) with their MMSE scores using linear regression models.

Classification tree models were used to explore the relative importance of patients’ demographic and health variables in identifying patients with normal cognitive functioning (MMSE > 26), concerns for MCI (20 < MMSE ≤ 26), or concerns for dementia (MMSE ≤ 20). Classification tree model is a nonparametric statistical method used to formulate decision rules, with no prior assumption regarding the distribution of the predictor variables. The classification tree model is fitted by recursively partitioning the data into increasingly homogeneous subgroups until no further improvements can be made (Clark & Pregibon, 1992).

The classification tree models were conducted using the “rpart” package (Therneau, Atkinson, & Ripley, 2015) in R, implementing the classification and regression tree (CART; Breiman, Friedman, Stone, & Olshen, 1984) methodology. The optimum tree models were derived using 10-fold cross-validation, and 20 minimum cases in parent node. “rpart” utilizes the Gini index to determine which variable (i.e., the primary splitter) gives the best split.3 After the data are separated, the process is applied to each subgroup, and continued recursively until no further improvement can be made or the subgroups reached a minimum size (seven in these data). In addition to the primary splitters (i.e., the variable that provides the best split at the node), candidate splitters (i.e., variables that give the second and third splits at the node) are also identified. These candidate splitters are considered as important variables, but are not used in the actual splitting of the classification tree. In this study, only the variable that provided the best split at a node was presented.

Because of the hierarchical structure of classification tree models, it is possible to identify the relative importance of each variable included in the fitted tree models (Qian, 2010). The importance of the predictor variables was estimated using varImp() in the “caret” package (Knuh, 2016). The measure of variable importance is computed as the sum of the improvement measure attributable to each predictor variable in each split for which it was a primary or candidate (i.e., important but not used in a split) splitter. The variable importance measure is scaled to be between 0 (the least important) and 100 (the most important).

Results

There were no statistically significant differences in age, level of education, number of medications, or the total number of vascular risk factors between men and women. Closer examination of the six vascular risk factors showed that women were significantly more likely to be obese than men, χ2(1) = 5.1, p = .02). The proportion of patients with any of the remaining vascular risk factors (smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and history of stroke) did not differ by gender.

The average MMSE score for the total sample was 25.51 (SD = 3.54), which is slightly lower than the cutoff for MCI (MMSE ≤ 26) (Folstein et al., 1975). As expected, patients with higher levels of education also had significantly higher MMSE scores than those with lower levels of education (t = 6.46, p < .0001). Simple linear regression showed that women had significantly higher MMSE scores than men (t = 3.24, p = .002). There was no interaction between education level and gender such that when the interaction term was included in the multivariate linear regression, only the main effect of education remained statistically significant (t = 4.93, p < .0001), indicating that education level is associated with higher MMSE scores. There were no significant differences in MMSE scores by patients’ age, number of medications, or the total number of vascular risk factors.

Using the cognitive cutoffs described above, patients were categorized as having normal cognitive functioning (MMSE > 26), concern for MCI (20 < MMSE ≤ 26), or concern for dementia (20 ≤ MMSE), based on their MMSE scores. Of the sample, 47 (50%) participants were identified as having normal cognitive functioning, 37 (39.36%) as having concerns for MCI, and 10 (10.64%) as having concerns for dementia. We further aggregated patients in the MCI and dementia groups into a “nonnormal” group (MMSE ≤ 26), indicating that these patients (n = 47) fell below normal expectation of cognitive functioning, as assessed with the MMSE.

Next, we used classification tree models to identify demographic and health variables associated with cognitive impairment, as assessed with the MMSE. As not all candidate variables are equally important in explaining the variation of cognitive impairment, classification tree models can serve as a means of variable selection to determine (a) the importance of each demographic and health characteristic to the classification of a patient within the MMSE cognitive diagnosis (normal, MCI, dementia) and (b) the importance of each demographic and health characteristic to the classification of patients within the normal versus nonnormal categories.

Model 1: Normal/MCI/Dementia Classification

A three-level classification tree was constructed when demographic and health characteristics (patients’ age, gender, education level, number of medications, and number of vascular risk factors) were used to statistically classify patients into normal, MCI, or dementia groups (Figure 1). Each node on the classification tree represents the most likely classification outcome in the observations (normal, MCI, or dementia). The numbers below each node indicate the number of observations in the normal, MCI, and dementia class, respectively. The sum of the numbers below each node represents the number of patients who are in the corresponding branch. Starting from the top of the figure, the node “Normal” indicates that the majority of the patients were classified as normal. The numbers 47/37/10 below the node indicate that, among the 94 patients (47 + 37 + 10) in the study, 47 patients were classified as normal, 37 as MCI, and 10 as in the dementia category.

Figure 1.

Classification tree categorizing normal, MCI, and dementia cognitive functioning using demographic and characteristics (age, gender, education, number of medications, and number of vascular risk factors).

Note. The numbers below each classification outcome indicate the number of observations in the normal, MCI, and dementia class, respectively. For example, 47/37/10 in the first node indicates that, among the 94 patients (47 + 37 + 10) in the study, 47 patients were classified as having normal cognitive functioning, 37 as having MCI, and 10 as having dementia. Normal: Normal cognitive functioning (MMSE > 26); MCI: concern for mild cognitive impairment (20 < MMSE ≤ 26); Dementia: Concern for dementia (20 ≤ MMSE). MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

Education was the variable used for the first split, separating patients into those with at least 9 years of education (left branch) and those with less than 9 years of education (right branch). This is considered to be the first level of the classification tree. The “Normal” node (left branch) indicates that 67 patients (41 + 26 + 0) had at least 9 years of education. Among them, the majority (41 out of 67) was classified as normal, 26 were classified as MCI, and none were classified as dementia. The “MCI” node (right branch) indicates that 27 patients (6 + 11 + 10) had less than 9 years of education. Among these patients, six were classified as normal, 11 as MCI, and 10 as dementia.

Focusing on the patients with at least 9 years of education (left branch), education was also used for the second split, further separating patients with at least 9 years of education into those with at least 12 years of education (left branch) and those with less than 12 years of education (right branch). Among the 39 patients (28 + 11) with at least 12 years of education, 28 were classified as normal and 11 as MCI. There were 28 patients (13 + 15) with between 9 and 11 years of education: 13 of them were classified as normal and 15 as MCI. This group of patients was further split using the number of vascular risk factors. Among the 12 patients who had less than three vascular risk factors, nine were classified as normal and three as MCI. As for the 16 patients who had three or more vascular risk factors, four were classified as normal and 12 in the MCI group.

Turning to the patients with less than 9 years of education (right branch on first level), the number of medication was used to further split these patients into those with at least 10 medications (left branch) and those with less than 10 medications (right branch). Of the 11 patients who had at least 10 medications, two were classified as normal, seven as MCI, and two in the dementia group. Among the 16 patients with fewer than 10 medications, four were classified as normal, four as MCI, and eight in the dementia group.

According to this model, individuals with less than 9 years of education and fewer than 10 prescribed medications were most likely to fall into the concerns for dementia group. Individuals with more than 12 years of education were more likely to be in the normal group.

Of the five demographic and health characteristics, patients’ education level was the most important variable used for classification in this model. This finding is consistent with the strong correlation found between MMSE scores and education level described in the above section. The misclassification rate of this classification tree model is 31.91%, indicating that more than two thirds of the patients were correctly classified into different cognitive functioning groups (normal/MCI/dementia) using only their demographic and health features.

Model 2: Normal/Nonnormal Classification

When demographic and health characteristics were used to classify patients as having normal versus nonnormal cognitive function, a three-level classification tree was also constructed (Figure 2). Consistent with the first model, education was used as the first and second splits; 39 patients (28 + 11) had at least 12 years of education (left branch) and 55 (19 + 36) had less than 12 years of education (right branch). For patients who had at least 12 years of education, the majority was classified as normal (28 out of 39) and fewer as nonnormal (11 out of 39). As for patients with less than 12 years of education, more than half (36 out of 55) were classified as nonnormal and fewer (19 out of 55) as normal. These patients were further split into those with less than 9 years of education (right branch) and those with at least 9 years of education (left branch). Among the patients who had less than 9 years of education, the majority (21 out of 27) had nonnormal cognitive function and few (6 out of 27) had normal cognitive function. As for patients who had between 9 and 12 years of education, 13 were classified as normal and 15 as nonnormal. The number of vascular risk factors was used to further split this group of patients. Among the 12 patients with less than three vascular risk factors, nine were classified as normal and three as nonnormal. As for those with at least three vascular risk factors, four were classified as normal and 12 as nonnormal.

Figure 2.

Classification tree categorizing normal and nonnormal cognitive functioning using demographic and health characteristics (age, gender, education, number of medications, and number of vascular risk factors).

Note. The numbers below each classification outcome indicate the number of observations in the normal and nonnormal class, respectively. For example, 28/11 in the left-mode node indicates that, among the 39 patients (28 + 11) who have at least 12 years of education, 28 were classified as having normal cognitive functioning, whereas 11 were classified as having nonnormal cognitive functioning. Normal: Normal cognitive functioning (MMSE > 26); Nonnormal: Concern for mild cognitive impairment or dementia (MMSE ≤ 26). MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

Overall, this model showed that patients with more education (at least 12 years of education) were more likely to have normal cognitive functioning, whereas those with less education (less than 9 years of education) were more likely to demonstrate nonnormal cognitive functioning, as measured with the MMSE. For patients with between 9 and 12 years of education, those with fewer than three vascular risk factors were more likely to have normal cognitive functioning, whereas those with at least three vascular risk factors were more likely to show nonnormal cognitive functioning. With only two categories of cognitive functioning to classify, this model’s rate of misclassification was 25.53%, meaning that only one quarter of the patients were incorrectly classified into different cognitive functioning groups (normal/MCI/dementia) when only their demographic and health features were available.

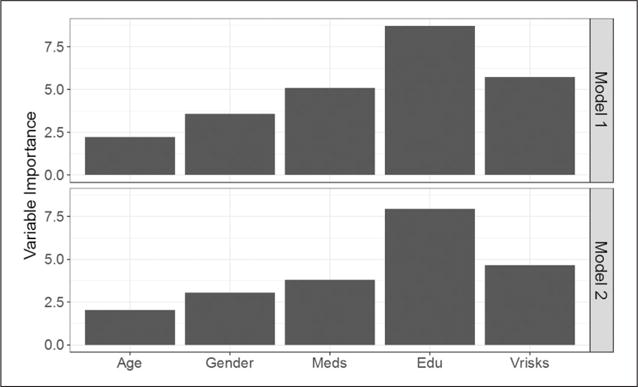

The relative importance of the predictor variables (age, gender, education level, number of medications, and number of vascular risk factors) was evaluated for both Models 1 and 2. The measure of importance was scaled to have a maximum value of 100, with higher scores indicating more importance. As shown in Figure 3, education level was the most important variable for both models, followed by the number of vascular risk factors and the number of medications. However, patients’ gender and age were relatively less important in classifying patients into varying degrees of cognitive functioning, and were not used in the construction of the classification trees.

Figure 3.

Variable importance estimated for each classification tree model. Model 1: Normal/MCI/dementia classification. Model 2: Normal/nonnormal classification.

Note. Meds = number of medication; Edu = education level; Vrisks = number of vascular risk factors.

Discussion

The aims of this study were to provide real-life clinical applicability in the relationship between MMSE scores, demographic and health variables that are important in identifying older African American patients with increased risk for cognitive impairment. The current study adds to the existing literature by providing guidelines to help primary care physicians identify patients with higher concerns for cognitive impairment using classification tree modeling, which investigates nonlinear associations and interactions among variables. The participants included older African Americans coming to see their primary care physicians for reasons other than cognitive complaints.

Among our sample of older African American adults, the average MMSE scores were slightly lower than the traditional cutoff point of 26 for MCI (Folstein et al., 1975), with approximately half of the individuals scoring below the cutoff point. It is possible that MMSE is not the ideal instrument to screen for cognitive deficits among African Americans, as previous studies suggested that the rates of false positive were higher among African Americans than Caucasians (Fillenbaum et al., 1990; Stephenson, 2001). However, it is possible that some of the patients who scored lower than the cutoff for normal cognitive functioning (MMSE > 26) had cognitive impairment that was undetected or unreported by their primary care physicians. Recent evidence showed that primary care physicians had difficulty identifying patients with early signs of cognitive impairment and were poor at recording such observations in medical records (Mitchell et al., 2011).

Consistent with previous studies (Callahan et al., 1996; Crum, Anthony, Bassett, & Folstein, 1993; Marcopulos et al., 1997), the current sample MMSE performance was strongly influenced by years of education; less-educated individuals were more likely to score lower on the MMSE than those with more education. Although age is often associated with increased cognitive impairment (Bachman et al., 1992; Evans et al., 1989; Hawkins et al., 2011; Marcopulos & McLain, 2003; Marcopulos et al., 1997; Unverzagt et al., 2001), MMSE performance was not associated with participants’ ages in the current study. This null finding suggests that older African American adults did not necessarily have worse cognitive performance than their younger counterparts; age was not predictive of worse performance. Medication and the total number of vascular risk factors did not influence MMSE performance, suggesting that the sheer number of either medications prescribed or vascular risks may not be directly associated with participants’ cognitive health.

Consistent with previous studies, results from classification tree models showed that education was the most important variable in identifying African American individuals with potential risk for poor performance on the MMSE. In our study, older African Americans with less than 9 years of education were more likely to score below the MMSE cutoff for normal cognition, whereas MMSE performance for individuals who had at least high school–level education is most likely to be within the range of normal cognition. Given the strong association between education level and MMSE scores in the literature (Callahan et al., 1996; Crum et al., 1993; Marcopulos et al., 1997) and the present study, this finding was not surprising. These results suggest that education may potentially be a protective factor against cognitive impairment (Stern et al., 1994), by providing a reserve of brain capacity that buffers against cognitive and functioning impairment (Callahan et al., 1996).

However, the detection of cognitive impairment may be more difficult among individuals with higher educational attainment (Stern et al., 1994). It is possible that the MMSE lacks the sensitively to detect early signs of dementia (Simard, 1998), especially among those with high education levels. It is possible that the recognition of cognitive impairment among higher educated patients may be delayed or even unrecognized by their primary care physicians, resulting in inadequate recognition, documentation, and/or reporting of potentially treatable conditions. Treatment may be further delayed as African Americans, in comparison with Whites, were more likely to associate cognitive impairment as a typical aspect of aging (Burns et al., 2006; Connell et al., 2009; Potter et al., 2009). Downstream effects could be poorer adherence to treatment by patients, higher rates of inpatient services, and increased Medicare costs among African Americans due to more severe cognitive impairment (Husaini et al., 2003). Because treatment is started later in the progression of the disease, it may be more difficult to manage for both the patients and their caregivers. With evidence suggesting people with higher education experience faster cognitive decline after the onset of AD (Roselli et al., 2009; Scarmeas, 2005; Stern, Albert, Tang, & Tsai, 1999), it is crucial for primary care physicians to be aware of signs of cognitive impairment among this group of older adults to initiate treatment at earlier stages of the disease.

Using classification tree models, our findings showed that the number of medications and number of vascular risk factors were important in identifying individuals with potential concerns for cognitive impairment among those with less than a high school–level education. Among African American individuals with less than 9 years of education, the number of prescribed medications was important in distinguishing those who were more demented versus those who had MCI. We speculate that less-educated patients taking more medications may experience better control of vascular risk factors, and possibly other health issues, enabling them to maintain MCI status. In contrast, less-educated patients with fewer medications may have uncontrolled and/or undiagnosed vascular risk factors associated with cognitive impairment, which may have contributed to the substantial cognitive impairment. It is also possible that less-educated patients with dementia may be less likely to report medical problems, do not receive appropriate treatment for them, and therefore are taking fewer medications. To understand the link between the number of medications and dementia among older African Americans with limited education, longitudinal research is needed to examine whether, and how, specific medications may be contributing to the delay of cognitive impairment among this group of elders.

The number of vascular risk factors was found to be important in distinguishing between normal and suboptimal MMSE scores among African American patients who finished middle school but not high school. Our results indicate that moderately educated African Americans with 9 to 12 years of education and fewer vascular risk factors were likely to demonstrate normal cognitive functioning. However, African Americans with the same amount of education but more vascular risk factors were less likely to demonstrate cognitive functioning within the normal range. This is consistent with findings that vascular risk factors are associated with impaired cognitive functioning and dementia (Duron & Hanon, 2008; Unverzagt et al., 2007). The current findings suggest that the comorbidities of vascular risk factors might have a more substantial impact on cognitive functioning among older African Americans with moderate levels of education than those with higher levels of education, highlighting the treatment of vascular risk factors as a promising means for the prevention of dementia.

Our finding that health variables were important for specific groups of elderly African American has practical implications. Due to the strong correlation between education level and MMSE scores, it may be reasonable to use education level as a proxy for cognitive reserve to identify individuals who may be more at risk for severe cognitive impairment, such as dementia. Nonetheless, in response to concerns about education bias in MMSE scores (Jones & Gallo, 2001), our results suggest that the number of prescribed medications may be useful in screening for those who may be experiencing cognitive difficulties among less-educated individuals. Among less-educated African American elderly, prescription of fewer medications may suggest undocumented medical difficulties. For instance, patients with dementia may underreport medical problems during outpatient visits relative to individuals without dementia, despite having similar levels of medical comorbidity (McCormick et al., 1994). Among a sample of older outpatients evaluated for dementia, approximately half of the patients were found to have a treatable medical problem that was previously undiagnosed (Larson, Reifler, Featherstone, & English, 1984). Taken together with the findings of the current study, physicians need to be especially alert to cognitive impairment and underreported medical problems in less-educated patients to avoid missed diagnoses and subsequent lack of treatment.

In the current sample, African American individuals with some high school education are likely to demonstrate cognitive functioning within the range indicative of MCI on the MMSE. However, as the cognitive performance of people with MCI overlaps with that of people with normal functioning and dementia (Morris et al., 1991; Rubin, Morris, Grant, & Vendegna, 1989; Storandt & Hill, 1989), it is more difficult to project the trajectories of cognitive decline for elders with MCI. Our findings suggest that the number of vascular risk factors may be a health variable to aid screening for those at increased risk for cognitive difficulties among those who have some high school education but did not graduate. With a moderate amount of education, elderly African Americans with more vascular risk factors may be at increased risk for cognitive impairment, as compared with those with fewer vascular risk factors. One may also posit that patients with impaired cognitive functioning may have difficulties with health management, thus resulting in more vascular risk factors than those with normal cognition. This finding adds to existing literature by showing that vascular risk factors may be especially important in identifying cognitive impairment among African American patients with 9 to12 years of education. Nonetheless, longitudinal studies are needed to further investigate the extent to which the number of vascular risk factors may be associated with cognitive impairment among African American elders with a moderate amount of education.

Due to the shortage of primary care physicians (Altschuler, Margolius, Bodenheimer, & Grumbach, 2012), physicians are often burdened by the large number of patients to be seen with limited appointment time allocated for each patient (Wilkins et al., 2007). Primary care physicians may only be able to attend to the most pressing problems at any one visit. Previous studies have suggested higher MMSE cutoff scores to increase the diagnostic accuracy of the MMSE among patients with higher education (O’Bryant et al., 2008; Spering et al., 2012). Increased knowledge of sociodemographic and health risk factors among specific groups of individuals may further help physicians become aware of patients at increased risk for cognitive impairment, warranting further dementia screening.

The use of classification tree models in the current study allows us to identify variables that are important in classifying African American elders with different levels of cognitive functioning. Results of the classification tree models suggest that the number of medications and vascular risk factors documented on a patients’ medical chart may help primary care physicians identify patients who are more at risk of cognitive impairment. A major advantage of the classification tree models is that they provide a set of decision rules that can be easily implemented in clinical practice. For instance, if a patient has at least 9 years of education, and has at least three vascular risk factors, the primary care physician should be aware that the patient is at increased risk for MCI. Similarly, if a patient with less than 9 years of education and is taking fewer than 10 medications, the primary care doctor should be aware that the patient is at high risk for dementia and a dementia evaluation may be in order.

Considering the recent Medicare requirement for primary care physicians to conduct cognitive assessment in their elderly patients, findings from this study elucidate a set of key variables that can help physicians identify patients with concerns for cognitive impairment. Because the variables identified are typically readily available in patients’ medical records (e.g., vascular risk factors, number of medications), primary care physicians can make use of the classification tree models in this study to identify patients’ cognitive status, even without using specific cognitive assessment tools.

Limitations

A few limitations of the current study should be noted. First, given the cross-sectional nature of the study, it is unclear whether the associations between health variables and low MMSE scores are indicative of cognitive impairment or life-long functioning, and whether the importance of the variables remains consistent over time. A follow-up study with participants in the current study is in place to explore these questions. Second, the current sample consisted of a convenience sample of African American elders who were visiting their primary care physicians for routine care. Before we can generalize our findings to other older African Americans, replications using larger, representative samples are needed.

Third, education was operationalized as years of education in this study. The quality of education, rather than just year of education, has been found to be important in relation to cognitive impairment among African Americans (Carvalho, Rea, Parimon, & Cusack, 2014; Chin, Negash, Xie, Arnold, & Hamilton, 2012; Manly, Schupf, Tang, & Stern, 2005; Manly et al., 2003). Further research is warranted to investigate whether health variables found to be important for individuals with different levels of education are also important for those with different quality of education.

We also recognize that, by dichotomizing the presence and absence of vascular risk factors, the severity of different vascular risk factors was not taken into account. Nonetheless, the use of dichotomous indicators allowed us to examine the cumulative effect of multiple risk factors on African American elders’ cognitive functioning and offer practical suggestions to primary care physicians who primarily use the MMSE when screening for dementia. With our findings that the number of vascular risk factors is associated with African American elders’ cognitive performance, it is important to further investigate how the severity of different vascular risk factors may have differential impact on elders’ cognitive ability. In addition, future work is needed to better understand the specific classes of medications that are associated with cognitive impairment.

Conclusion

Among a sample of older African Americans, with no previous diagnosis of cognitive or memory problems, who were visiting their primary care physicians for nonmemory-related reasons, average cognitive performance was slightly below the MMSE cutoff for normal cognition. Consistent with existing studies, education level was strongly associated with cognitive functioning. For patients with different levels of education, the total number of prescribed medications and vascular risk factors were found to be important variables in identifying those with cognitive difficulties. Our findings suggest that the MMSE may be used to detect signs of cognitive impairment among individuals with low to moderate levels of education, but may not be sensitive enough to detect cognitive impairment among individuals with high levels of education. Although the MMSE may be a crude instrument to screen for cognitive impairment and dementia, the MMSE is widely used in clinical practice, and poor MMSE performance may represent inadequate health management, poorer health outcomes, and decreased ability to adhere to medical treatment plans. Taking into account the number of prescribed medications and vascular risks may improve the ability to identify individuals at increased risk for cognitive impairment and help them take steps to mitigate the progression and impact of cognitive difficulties. Among patients with at least high school–level education, primary care physicians should be aware that patients with more than three vascular risk factors are potentially at higher risk for cognitive difficulties. As for patients with less than high school–level education, those who are taking fewer medications may be at risk for more severe cognitive impairment than those who are taking more medications.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported in part by Award 13-4 from the Commonwealth of Virginia’s Alzheimer’s and Related Diseases Research Award Fund, administered by the Virginia Center on Aging, School of Allied Health, Virginia Commonwealth University. This study was also supported in part by Hoos for Memory at the University of Virginia. Siny Tsang is supported by the research training grant 5-T32-MH 13043 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Biographies

Siny Tsang, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow in the Psychiatric Epidemiology Training program in the Department of Epidemiology at Columbia University. Her research focuses on measurement issues in assessing personality disorders and health, as well as examining the change and stability of personality across the life span.

Scott A. Sperling is a clinical neuropsychologist and assistant professor of clinical neurology at the University of Virginia. His clinical specialties include neuropsychological assessment in neurodegenerative diseases and behavioral/environmental management of cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms. His clinical research interests include evaluation of the relationships between cognition, behavior, and health variables, as well as evaluation of new initiatives aimed at improving dementia care.

Moon-Ho Park, MD, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Neurology at the Korea University College of Medicine, Republic of Korea. His research focuses on aging health issue and design, testing, and scaling methods for older population.

Ira M. Helenius, MD, MPH, is an associate professor of medicine in the Division of General Medicine at the University of Virginia. Since 2011, she has served as the medical director of University Medical Associates, the University of Virginia’s Internal Medicine Teaching clinic. Her scholarly work focuses on ambulatory clinic redesign and training in ambulatory medicine.

Ishan C. Williams, PhD, is an assistant professor at the University of Virginia, School of Nursing. Her current research focuses on quality of life issues among older adults with dementia and their family caregivers, chronic disease management for older adults with type 2 diabetes, and a study on the link between cognition and vascular problems among older African American adults.

Carol Manning, PhD, ABPP-CN, is the director of the Memory Disorders Clinic, director of the Neurobehavioral Assessment Laboratory, associate professor of Neurology and Vice Chair for Faculty Development in the Department of Neurology at the University of Virginia. She was appointed by the governor of Virginia to the Commonwealth of Virginia Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Commission.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The patients completed the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) on the same day of their visit to their primary care physicians. The primary care physician examined the patient, performed necessarily tests, and reviewed the medical records to ensure they were correct and up to date.

Upon reviewing the patients’ medical records, we were unable to determine whether all the medications were current prescriptions or not. It is possible that some prescriptions were expired but were not removed from the documentation.

Gini index is defined as , where Di is the deviance (or “impurity”) for the ith node, gi is the number of classes in the node, and pk is the proportion of observations in class k. For a pure node, in which all observations belong to one class, Di = 0.

References

- Albert SM, Teresi JA. Reading ability, education, and cognitive status assessment among older adults in Harlem, New York City. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:95–97. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler J, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Estimating a reasonable patient panel size for primary care physicians with team-based task delegation. Annals of Family Medicine. 2012;10:396–400. doi: 10.1370/afm.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Smailagic N, Roqué i, Figuls M, Ciapponi A, Sanchez-Perez E, Giannakou A, Cullum S. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015:CD010783. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010783.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman DL, Wolf PA, Linn R, Knoefel JE, Cobb J, Belanger A, White LR. Prevalence of dementia and probable senile dementia of the Alzheimer type in the Framingham Study. Neurology. 1992;42:115–119. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker FM. Ethnic minority elders: A mental health research agenda. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1992;43:337–338342. doi: 10.1176/ps.43.4.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Alzheimer’s disease in African Americans: Risk factors and challenges for the future. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2014;33:580–586. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L, Friedman J, Stone C, Olshen R. Classification and regression trees. Belmont, CA: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Burns R, Nichols LO, Graney MJ, Martindale-Adams J, Lummus A. Cognitive abilities of Alzheimer’s patients: Perceptions of Black and White caregivers. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2006;62:209–219. doi: 10.2190/3GG6-8YV1-ECJG-8XWN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Hall KS, Hui SL, Musick BS, Unverzagt FW, Hendrie HC. Relationship of age, education, and occupation with dementia among a community-based sample of African Americans. Archives of Neurology. 1996;53:134–140. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550020038013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho A, Rea IM, Parimon T, Cusack BJ. Physical activity and cognitive function in individuals over 60 years of age: A systematic review. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2014;9:661–682. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S55520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin AL, Negash S, Hamilton R. Diversity and disparity in dementia: The impact of ethnoracial differences in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2011;25:187–195. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318211c6c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin AL, Negash S, Xie S, Arnold SE, Hamilton R. Quality, and not just quantity, of education accounts for differences in psychometric performance between African Americans and White non-Hispanics with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2012;18:277–285. doi: 10.1017/s1355617711001688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Pregibon D. Tree-based models. In: Chambers JM, Hastie TJ, editors. Statistical models in S. Pacific Grove, CA: Wadsworth & Brooks; 1992. pp. 377–419. [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Scott Roberts J, McLaughlin SJ, Akinleye D. Racial differences in knowledge and beliefs about Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2009;23:110–116. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318192e94d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Carpenter I, Katona C, Schroll M, Wagner C, Fialova D, Livingston G. The AdHOC Study of older adults’ adherence to medication in 11 countries. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13:1067–1076. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.12.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Tandy AR, Balamurali TB, Livingston G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of ethnic differences in use of dementia treatment, care, and research. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;18:193–203. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181bf9caf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;269:2386–2391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirovic J, Prineas R, Loewenstein D, Bean J, Duara R, Sevush S, Szapocznik J. Prevalence of dementia in three ethnic groups: The South Florida program on aging and health. Annals of Epidemiology. 2003;13:472–478. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(02)00437-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duron E, Hanon O. Vascular risk factors, cognitive decline, and dementia. Vascular Health and Risk Management. 2008;4:363–381. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DA, Funkenstein HH, Albert MS, Scherr PA, Cook NR, Chown MJ, Taylor JO. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in a community population of older persons. Higher than previously reported. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;262:2551–2556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Harvey D, DeCarli C. Progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia in clinic- vs community-based cohorts. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66:1151–1157. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum G, Heyman A, Williams K, Prosnitz B, Burchett B. Sensitivity and specificity of standardized screens of cognitive impairment and dementia among elderly Black and White community residents. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1990;43:651–660. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90035-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatry Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins KA, Cromer JR, Piotrowski AS, Pearlson GD. Mini-Mental State Exam performance of older African Americans: Effect of age, gender, education, hypertension, diabetes, and the inclusion of serial 7s subtraction versus “world” backward on score. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2011;26:645–652. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acr054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes TL, Larimer N, Adami A, Kaye JA. Medication adherence in healthy elders: Small cognitive changes make a big difference. Journal of Aging and Health. 2009;21:567–580. doi: 10.1177/0898264309332836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman A, Fillenbaum G, Prosnitz B, Raiford K, Burchett B, Clark C. Estimated prevalence of dementia among elderly black and white community residents. Archives of Neurology. 1991;48:594–598. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530180046016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husaini BA, Sherkat DE, Moonis M, Levine R, Holzer C, Cain VA. Racial differences in the diagnosis of dementia and in its effects on the use and costs of health care services. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:92–96. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RN, Gallo JJ. Education bias in the mini-mental state examination. International Psychogeriatrics. 2001;13:299–310. doi: 10.1017/s1041610201007694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuh M. caret: Classification and Regression Training. 2016 (Version R package version 60-73). Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/package=caret.

- Larson EB, Reifler BV, Featherstone HJ, English DR. Dementia in elderly outpatients: A prospective study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1984;100:417–423. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-3-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemsky CM, Smith G, Malec JF, Ivnik RJ. Identifying risk for functional impairment using cognitive measures: An application of CART modeling. Neuropsychology. 1996;10:368–375. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.10.3.368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Touradji P, Small SA, Stern Y. Reading level attenuates differences in neuropsychological test performance between African American and White elders. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2002;8:341–348. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702813157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Schupf N, Tang MX, Stern Y. Cognitive decline and literacy among ethnically diverse elders. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2005;18:213–217. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Touradji P, Tang MX, Stern Y. Literacy and memory decline among ethnically diverse elders. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2003;25:680–690. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.680.14579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcopulos BA, McLain C. Are our norms “normal?” A 4-year follow-up study of a biracial sample of rural elders with low education. Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2003;17:19–33. doi: 10.1076/clin.17.1.19.15630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcopulos BA, McLain CA, Giuliano AJ. Cognitive impairment or inadequate norms? A study of healthy, rural, older adults with limited education. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1997;11:111–131. doi: 10.1080/13854049708407040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick WC, Kukull WA, van Belle G, Bowen JD, Teri L, Larson EB. Symptom patterns and comorbidity in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1994;42:517–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb04974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta KM, Simonsick EM, Rooks R, Newman AB, Pope SK, Rubin SM, Yaffe K. Black and White differences in cognitive function test scores: What explains the difference? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:2120–2127. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Pentzek M. Clinical recognition of dementia and cognitive impairment in primary care: A meta-analysis of physician accuracy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2011;124:165–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, McKeel DW, Jr, Storandt M, Rubin EH, Price JL, Grant EA, Berg L. Very mild Alzheimer’s disease: Informant-based clinical, psychometric, and pathologic distinction from normal aging. Neurology. 1991;41:469–478. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Bryant SE, Humphreys JD, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Graff-Radford NR, Petersen RC, Lucas JA. Detecting dementia with the Mini-Mental State Examination in highly educated individuals. Archives of Neurology. 2008;65:963–967. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.7.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza O, Clark JH, O’Bryant SE, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Graff-Radford NR, Lucas JA. Diagnostic validity of age and education corrections for the Mini-Mental State Examination in older African Americans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60:328–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Geda YE, Ivnik RJ, Ivnik RJ., Jr Mild cognitive impairment: Ten years later. Archives of Neurology. 2009;66:1447–1455. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter GG, Plassman BL, Burke JR, Kabeto MU, Langa KM, Llewellyn DJ, Steffens DC. Cognitive performance and informant reports in the diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia in African Americans and Whites. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2009;5:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.04.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian SS. Environmental and ecological statistics with R. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2010. Applied Environmental Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. Available from http://www.r-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Roselli F, Tartaglione B, Federico F, Lepore V, Defazio G, Livrea P. Rate of MMSE score change in Alzheimer’s disease: Influence of education and vascular risk factors. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2009;111:327–330. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin EH, Morris JC, Grant EA, Vendegna T. Very mild senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. I. Clinical assessment. Archives of Neurology. 1989;46:379–382. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520400033016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarmeas N. Education and rates of cognitive decline in incident Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2005;77:308–316. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.072306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadlen MF, Siscovick D, Fitzpatrick AL, Dulberg C, Kuller LH, Jackson S. Education, cognitive test scores, and Black-White differences in dementia risk. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:898–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard M. The Mini-Mental State Examination: Strengths and weaknesses of a clinical instrument. The Canadian Alzheimer Review. 1998;2:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Spering CC, Hobson V, Lucas JA, Menon CV, Hall JR, O’Bryant SE. Diagnostic accuracy of the MMSE in detecting probable and possible Alzheimer’s disease in ethnically diverse highly educated individuals: An analysis of the NACC Database. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2012;67:890–896. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson J. Racial barriers may hamper diagnosis, care of patients with Alzheimer disease. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286:779–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y, Albert S, Tang MX, Tsai WY. Rate of memory decline in AD is related to education and occupation: Cognitive reserve? Neurology. 1999;53:1942–1947. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y, Gurland B, Tatemichi TK, Tang MX, Wilder D, Mayeux R. Influence of education and occupation on the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271:1004–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storandt M, Hill RD. Very mild senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. II. Psychometric test performance. Archives of Neurology. 1989;46:383–386. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1989.00520400037017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappen RM, Rosselli M, Engstrom G. Use of the MC-FAQ and MMSE-FAQ in cognitive screening of older African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and European Americans. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;20:955–962. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31825d0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therneau T, Atkinson B, Ripley B. rpart: Recursive Partitioning and Regression Trees (Version R package version 4.1-10) 2015 Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/package=rpart.

- Unverzagt FW, Gao S, Baiyewu O, Ogunniyi AO, Gureje O, Perkins A, Hendrie HC. Prevalence of cognitive impairment: Data from the Indianapolis Study of Health and Aging. Neurology. 2001;57:1655–1662. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.9.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unverzagt FW, Sujuan G, Lane KA, Callahan C, Ogunniyi A, Baiyewu O, Hendrie HC. Mild cognitive dysfunction: An epidemiological perspective with an emphasis on African Americans. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2007;20:215–226. doi: 10.1177/0891988707308804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins CH, Wilkins KL, Meisel M, Depke M, Williams J, Edwards DF. Dementia undiagnosed in poor older adults with functional impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:1771–1776. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RY, Giuliano KK, Bignell CU, Pritham WW. Assessing cognitive ability in research: Use of MMSE with minority populations and elderly adults with low education levels. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2006;32:45–54. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20060401-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]