Abstract

This study investigated how well components of the psychopathy trait are measured among college students with the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (LSRP), the Personality Assessment Inventory–Antisocial Features Scale (PAI ANT), the Psychopathic Personality Inventory–Short Form (PPI-SF), and the Self-Report Psychopathy Scale-II (SRP-II). Using Samejima (1969)’s graded response model (GRM), the subscales were found to vary in their ability to measure the corresponding latent traits. The LSRP primary psychopathy factor is more precise in measuring the latent trait than the secondary psychopathy factor. The PAI ANT items show coherent psychometric properties, whereas the PPI-SF factors differ in their precision to measure the corresponding traits. The SRP-II factors are effective in discriminating among individuals with varying levels of the latent traits. Results suggest that multiple self-report measures should be used to tap the multidimensional psychopathy construct. However, there are concerns with respect to using negatively worded items to assess certain aspects of psychopathy.

Keywords: psychopathy, item response theory, self-report psychopathy measure

Conceptualized as a personality disorder with distinctive interpersonal-affective and behavioral characteristics, the majority of research on the latent trait of psychopathy was conducted among forensic samples using the Psychopathy Checklist (PCL; Hare, 1980) and its revision, the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R; Hare, 1991, 2003). Earlier factor analytic studies of the PCL and the PCL-R among adult samples suggested the latent psychopathy trait is underpinned by a two-factor structure, reflecting interpersonal/affective traits and antisocial behavioral characteristics (e.g., Hare, 1980, 1991; Harpur, Hare, & Hakstian, 1989). However, subsequent research has suggested a three-factor model that excluded the antisocial behavior items (Cooke & Michie, 2001), and a four-factor model (Hare, 2003; Vitacco, Roger, Neumann, Harrison, & Vincent, 2005), which reincorporated antisocial content. In addition to the controversies of the number of dimensions underlying the construct of psychopathy (Neumann, Kosson, & Salekin, 2007), concerns have been raised regarding whether antisocial behavior should be included as a core feature of the latent psychopathy trait (Hare & Neumann, 2010; Skeem & Cooke, 2010).

In response to the burgeoning interest in the study of the psychopathy trait among nonforensic populations (e.g., community, college), a number of self-report psychopathy measures have been developed, including the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (LSRP; Levenson, Kiehl, & Fitzpatrick, 1995), the antisocial features subscale in the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI ANT; Morey, 2007), the Psychopathic Personality Inventory–Short Form (PPI-SF; Lilienfeld, 1990), and the Self-Report Psychopathy-II (SRP-II; Hare, Harpur, & Hemphill, 1989). As self-report measures of psychopathy become more widely available, they are increasingly used in research studies. In fact, among the psychopathy studies published between 2000 and February 2014, more than half of the studies did not include the PCL-R and/or its variants in their abstracts or keywords, suggesting that self-report psychopathy measures may have been used instead of the PCL-R and its variants (Kelsey, Rogers, & Robinson, 2014). A brief review of the four self-report psychopathy measures is provided below.

Self-Report Measures of Psychopathy

The 26-item LSRP was developed to measure psychopathy in noninstitutionalized samples; two factors were generated from initial factor analysis, representing primary and secondary psychopathy (Levenson et al., 1995). Primary psychopaths are posited to be manipulative, callous, and extremely selfish, whereas secondary psychopaths tend to be impulsive and engage in antisocial behavior (Karpman, 1948). However, later studies were unable to replicate the original two-factor structure of the LSRP without modification (Brinkley, Schmitt, Smith, & Newman, 2001; Lynam, Whiteside, & Jones, 1999). Recently, a three-factor structure proposed to measure egocentricity, callousness, and antisocial features, using 19 of the 26 LSRP items, was found to fit well among samples of incarcerated inmates (Brinkley, Diamond, Magaletta, & Heigel, 2008; Sellbom, 2011), college students (Brinkley et al., 2008; Salekin, Chen, Sellbom, Lester, & Mac-Dougall, 2014; Sellbom, 2011), and community participants (Somma, Fossati, Patrick, Maffei, & Borroni, 2014). Despite promising model fit indices, the convergent and discriminant validity of the three-factor model remains questionable, whereas the convergent and discriminant validity of the two-factor model holds some value (Salekin et al., 2014).

To the best of our knowledge, only two published studies have examined the psychometric properties of the LSRP with an item response theory (IRT) framework. Gummelt, Anestis, and Carbonell (2012) found that the LSRP items vary in their ability to distinguish among undergraduate students with varying levels of psychopathy, with more than half of the items demonstrating differential item functioning (DIF) between genders. Using a Brazilian community sample, Hauck-Filho and Teixeira (2014) evaluated the extent to which items in the primary and secondary psychopathy subscales fit the Unidimensional Rating Scale model (RSM; Andrich, 1978). Results showed support for the two-factor model in this sample, with minimal DIF between genders. However, the authors did not further explore whether certain items are better or worse at discriminating respondents with varying levels of the latent trait.

The Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI; Morey, 1991, 2007) is a multiscale self-report instrument designed to measure an array of psychopathological constructs. Among the 11 PAI clinical scales, the Antisocial Features Scale (ANT) consists of items that assess features of antisocial personality, psychopathy, and criminality. Developed using Cleckley (1941) and Hare’s (1980, 1991) conceptualizations of the disorder, the PAI ANT emphasizes the personological features of the disorder (Morey, 2003), making the scale a favorable choice when assessing psychopathic characteristics in a nonoffending population. As with all the PAI subscales, the ANT items were written at a relatively low reading level (fourth grade), making it appealing for use in a wide variety of settings (Morey, 1996), especially when assessing psychopathy traits among community samples. Although there is limited research evaluating the ANT as a measure of psychopathy, the scale was found to have adequate psychometric properties (Morey, 2007; Siefert, Sinclair, Kehl-Fie, & Blais, 2009). Among offenders, ANT was reported to be positively associated with the total PCL-R and PPI scores, though the correlations were mainly driven by the antisocial/lifestyle factor (Edens, Hart, Johnson, Johnson, & Olver, 2000; Edens, Poythress, & Watkins, 2001). In addition, the ANT subscales were found to be associated with other self-report psychopathy measures among community samples (Benning, Patrick, Salekin, & Leistico, 2005; Salekin, Trobst, & Krioukova, 2001).

Lilienfeld (1990) developed the Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI) to measure central psychopathy characteristics in nonclinical samples. The 187 self-report items assess eight factor-analytically developed domains of psychopathy: (a) blame externalization, (b) social potency, (c) Machiavellian egocentricity, (d) fearlessness, (e) coldheartedness, (f) impulsive nonconformity, (g) stress immunity, and (h) carefree nonplanfulness. Selecting the seven items that had the highest factor loadings on each of the eight dimensions, an abbreviated version of the PPI, the 56-item PPI-SF, was constructed (see Lilienfeld, 1990). Subsequent studies showed that the eight PPI-SF domains can be combined into two higher order dimensions paralleling the two-factor structure of the PCL-R, however, the PPI-SF two-factor models derived have not always been consistent (e.g., Benning, Patrick, Hicks, Blonigen, & Krueger, 2003; Lilienfeld, 1990; Smith, Edens, & Vaughn, 2011; Wilson, Frick, & Clements, 1999). Although the PPI-SF was found to be highly correlated with the original version with adequate to high internal consistencies (Lilienfeld & Hess, 2001), concerns have been raised regarding the item selection process for the PPI-SF. For example, the underlying latent trait may be underrepresented by the abbreviated scales (Smith, McCarthy, & Anderson, 2000), and rarely endorsed items that are highly discriminating at either ends of the latent trait continuum may be excluded (Tonnaer, Cima, Sijtsma, Uzieblo, & Lilienfeld, 2012).

Adapted from the first version of the Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (SRP; Hare et al., 1989), the 60-item SRP-II was revised to parallel the two factors in the PCL-R (Hare, 1991), with items designated to measure interpersonal/affective features (nine items), social deviance characteristics (13 items), and both domains (nine items). However, there is limited research examining the factor structure of the SRP-II in community populations, and among those, results have been mixed. Although some studies identified a two-factor structure of the SRP-II, these models failed to mirror the structure of the PCL-R from which the SRP-II was derived (e.g., Benning et al., 2005; Williams & Paulhus, 2004). After making substantial revisions to the SRP-II, a four-factor solution that parallels the four-factor model of the PCL-R was proposed (Williams, Paulhus, & Hare, 2007). More recently, Lester, Salekin, and Sellbom (2013) proposed a rationally derived four-factor model from exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. This 36-item four-factor SRP-II maps well onto the PCL-R’s four-factor structure, assessing features of interpersonal, disinhibition/impulsivity, fearlessness, and coldheartedness. Although a third edition of the SRP has been developed (Paulhus, Neumann, & Hare, in press), this revision focused on adding items to assess antisocial behavior (Williams, Nathanson, & Paulhus, 2003), which is less relevant in nonforensic samples. The SRP-II has been found to remain useful in tapping the Cleckley psychopathic personality among nonforensic samples (Lester, Salekin, & Sellbom, 2013).

Collectively, the majority of the research on self-report psychopathy measures has focused on evaluating how well the self-report instruments map onto the factor structures of the PCL-R, and investigating whether correlates of psychopathic traits are similar among forensic and nonforensic populations. Thorough examination of how individual items function within these self-report measures of psychopathy has been lacking. With the exception of one study investigating the item properties of the LSRP (Hauck-Filho & Teixeira, 2014), we are unaware of any published IRT studies that examined the psychometric properties of the PAI ANT, PPI-SF, or SRP-II. Thus, whether self-report items assessing psychopathy among community populations are able to assess the different components of the psychopathy trait remains unknown. As these psychopathy measures rely on individuals’ self-reports, rather than trained clinicians’ assessments, it is critical to investigate if some items are more sensitive to varying levels of the latent trait than others, and whether certain items are more frequently endorsed than others.

The Current Study

In the present study, we utilized data from a large undergraduate student sample in which participants completed four self-report measures of psychopathy to explore how well the underlying trait of psychopathy is measured by each self-report instrument. Using an item response theory (IRT) approach, we attempted to answer two main questions:

Assuming the subscales within each instrument are measuring components of the underlying psychopathy trait, are the different domains of psychopathy measured equally well by the different subscales within an instrument?

As the four self-report instruments were developed to assess characteristics indicative of the latent psychopathy trait, are the latent constructs measured with different self-report instruments similar to one another?

To answer the first question, we examined (a) whether the items in different subscales (within the same instrument) are similarly discriminating; and (b) the range of the latent trait in which the items were positively endorsed. An optimal instrument for assessing the features indicative of the underlying psychopathy trait should mostly consist of items that are discriminating, as well as items that are endorsed in a wide range on the latent trait continuum. We aim to investigate whether certain subscales in the self-report psychopathy instruments are better at assessing features associated with the psychopathy trait, and whether the use of subscales can tap a broad range of psychopathic tendencies among nonforensic samples.

The second question is addressed by examining the extent to which the subscales (within and between different instruments) are associated with one another. For respondents who completed all four self-report measures, we explored such relations using (a) the total scores on each subscale computed by summing the item scores in each corresponding subscale, and (b) the underlying latent trait estimated from the item response theory analysis for each subscale. We expected moderate to strong correlations between subscales from different instruments that are assessing similar domain.

Method

Participants

The current study is a secondary data analysis of data collected from 1,257 (378 men, 869 women) undergraduate students enrolled in a southeastern university in the United States (see Lester et al., 2013), with ages between 17- and 51-years-old (M = 19.3, SD = 2.3). Most participants self-identified as Caucasians (81.54%), with 10.90% African Americans, and 5.01% of other racial/ethnic groups. Participants received course credit in exchange for their participation in the initial study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the university (IRB #02-JCH-037).

Measures

Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale (LSRP)

The LSRP (Levenson et al., 1995) is a 26-item instrument modeled after the PCL-R items; each item was scored on a 4-point ordinal scale (1 = disagree strongly, 2 = disagree somewhat, 3 = agree somewhat, 4 = agree strongly). Initial factor analysis showed that the LSRP consists of 16 items measuring the manipulative and uncaring attitude of primary psychopathy (PP), and 10 items assessing impulsivity and antisocial lifestyle of secondary psychopathy (SP).1

Personality Assessment Inventory-Antisocial Features Scale (PAI ANT)

The 24-item PAI ANT Scale (Morey, 2007) can be divided into three factors of eight items each, assessing antisocial behavior (A), egocentricity (E), and stimulus seeking (S). Each item was rated on a 4-point scale (0 = false/not at all true, 1 = somewhat true, 2 = mainly true, 3 = very true).

Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Short Form (PPI-SF)

The 56-item PPI-SF consists of items that have the highest factor loadings on the original PPI (Lilienfeld, 1990). The PPI-SF is comprised of eight 7-item factors: blame externalization (BE), social potency (SP), Machiavellian (ME), fearlessness (F), cold-heartedness (C), impulsive nonconformity (IN), stress immunity (SI), and carefree nonplanfulness (CN). Each item was scored on a 4-point scale (1 = false, 2 = mostly false, 3 = mostly true, 4 = true).

Self-Report Psychopathy Scale-II (SRP-II)

The SRP-II (Hare et al., 1989) includes a total of 60 items, in which each item was scored on a 7-point scale (1 = disagree strongly, 2 = disagree moderately, 3 = disagree slightly, 4 = neutral, 5 = agree slightly, 6 = agree moderately, 7 = agree strongly). A rationally derived 36-item four-factor model (Lester et al., 2013) was adopted in this study. The four factors are interpersonal (IP = 16 items), disinhibition/impulsivity (DI = nine items), fearlessness (F = five items), and coldheartedness (C = six items).

IRT Model

Considering that ordinal response categories are used in all four self-report measures of psychopathy, Samejima’s (1969) graded response model (GRM) was used. In the GRM, each item i with mi + 1 response categories is described by a slope parameter (αi) and j = 1 … mi category threshold parameters (βij). The estimated parameters can be represented graphically as category response curves (CRCs), where the number of CRCs corresponds to the number of response categories for each item i. The αi parameter can be considered as a discrimination parameter; it reflects how quickly the expected item score varies as a function of the latent trait level (Embretson & Reise, 2000). An item with a larger α has more narrow and peaked CRCs, whereas the CRCs of an item with a smaller α are flatter. The category thresholds (βij parameters) indicate the underlying trait levels needed to respond above the corresponding thresholds with 50% probability, which are reflected by the intersection points between two consecutive CRCs for item i, at which the probability of the next response category (mi) becomes equally likely as the previous category (mi−1).

The probability that a respondent’s score (x) on item i is at or above a category threshold (j = 1… mi), conditional on the latent trait level (θ), is computed as

where x = j = 1 …, mi. The probabilities of a respondent scoring in each response category conditional on the latent trait level are estimated separately as

As the LSRP, PAI ANT, and PPI-SF are scored on a 4-point ordinal scale, three βij parameters are estimated for each item in these measures. Six βij parameters are estimated for each of the SRP-II items, corresponding to the seven response categories. All GRM analyses were performed using Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012).

In IRT, the precision of measurement at different levels of the latent trait can be estimated with information functions (Embretson, 1996). Conceptually, item information function can be computed by taking the inverse of the square of the standard error of estimate (Baker, 1992; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). The sum of the corresponding item information functions in a scale constitutes a test information function (TIF), which reflects the collective measurement precision provided by the items that make up the scale (Bolt, Hare, Vitale, & Newman, 2004). The TIFs can also be graphically presented as test information curves (TICs), where the amount of information provided by a scale is plotted against the latent trait continuum. Across the latent trait continuum, locations in which the scale is precise in measuring the latent construct are reflected by high TICs, whereas the TICs are low in locations where the scale is not very precise. A TIC with a narrow peak suggests that the scale is precise, or able to distinguish respondents above or below a certain latent trait level, but not as precise at the extremes. On the other hand, a TIC that is smooth and flat indicates that the scale is able to measure respondents across a wide range of latent trait level with similar precision.

Comparisons Across Measures

Mann–Whitney U tests and Kruskal-Wallis H tests are used to compare the estimated IRT parameters (αis and βijs) across the self-report measures. Nonparametric tests are used as there is no underlying assumption that the residuals of the estimated IRT parameters follow a normal distribution.

The differences in measurement precision across measures are explored through inspection of the TIFs and TICs. We examined the amount of information provided by different measures, as well as the ranges of the latent trait in which various instruments are better at assessing the respective latent traits.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics of the self-report measures are presented in Table 1. For each of the self-report psychopathy measures in this study, a total score can be computed, with higher scores representing higher levels of psychopathy traits. Because these self-report measures of psychopathy were initially developed with varying factor structures to tap different components in the psychopathy construct, factor scores can also be generated by summing the items in each factor, reflecting strengths of endorsement in different domains of the psychopathy measures. This information can also be located in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Four Self-Report Measures of Psychopathy and Their Subscales

| Scale | Measure | Items | Mean (SD) | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSRP | Primary psychopathy | 16 | 29.44 (8.07) | 16 | 60 |

| Secondary psychopathy* | 9 | 19.77 (4.46) | 9 | 35 | |

| Total | 25 | 49.20 (10.74) | 25 | 89 | |

| PAI ANT | Antisocial behavior | 8 | 7.53 (5.22) | 0 | 24 |

| Egocentricity | 8 | 5.49 (3.80) | 0 | 24 | |

| Stimulus seeking | 8 | 8.18 (4.72) | 0 | 24 | |

| Total | 24 | 21.23 (11.33) | 0 | 71 | |

| PPI-SF | Blame externalization | 7 | 14.60 (4.48) | 7 | 28 |

| Social potency | 7 | 20.15 (4.18) | 7 | 28 | |

| Machiavellian | 7 | 14.94 (3.64) | 7 | 27 | |

| Fearlessness | 7 | 15.64 (5.04) | 7 | 28 | |

| Coldheartedness | 7 | 13.84 (3.19) | 7 | 27 | |

| Impulsive nonconformity | 7 | 13.80 (3.69) | 7 | 27 | |

| Stress immunity | 7 | 18.15 (4.28) | 7 | 28 | |

| Carefree nonplanfulness | 7 | 12.89 (3.12) | 7 | 24 | |

| Total | 56 | 124.04 (14.88) | 84 | 187 | |

| SRP-II | Interpersonal | 16 | 62.57 (15.72) | 20 | 109 |

| Disinhibition/Impulsivity | 9 | 22.38 (9.51) | 9 | 61 | |

| Fearlessness | 5 | 19.82 (6.54) | 5 | 35 | |

| Coldheartedness | 6 | 14.55 (6.37) | 6 | 36 | |

| Total | 36 | 119.31 (28.52) | 45 | 233 |

Note. LSRP = Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale; PAI ANT = Personality Assessment Inventory—Antisocial Features Scale; PPI-SF = Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Short Form; SRP-II = Self- Report Psychopathy Scale-II.

Item 17: “I find myself in the same kinds of trouble, time after time” is missing from the dataset.

Unidimensionality

It should be noted that evaluating the factor structures of the self-report measures was not the primary goal of the present study. Although the self-report measures are all assumed to assess the underlying psychopathy construct, all four measures have been proposed to consist of correlated factor structures. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were used to examine whether the unidimensional models are better fit than the theoretically driven factor models. For the LSRP, PAI ANT, and PPI-SF, the original factor structures were tested. The factor structure of the SRP-II was previously examined with the sample used in the current study (Lester et al., 2013); neither Hare et al.’s (1989) original two-factor model nor Benning, Patrick, Salekin, and Leistico (2005); 23-item two-factor model was found to achieve adequate fit in this sample. Thus, Lester et al.’s (2013) rationally derived 36-item four-factor model was used to test against a unidimensional SRP-II model. Across all four self-report measures, the factor models showed better fit than the unidimensional model; model fit indices are presented in supplementary material Appendix 1, Table 1.

We further examined the unidimensionality of each factor with the self-report measures using two criteria: (a) principal component analyses (PCAs) with polychoric correlations, and (b) the fit of a one-factor model to the polychoric correlation matrix. The first three eigenvalues (λ1, λ2, and λ3) from the PCAs are shown in Table 2. Using the UNIDI index: (λ1 − λ2)/(λ2 − λ3) > 5 (Martínez Arias, 1995, p. 297), all but three of the factors (LSRP’s SP, ANT-E, and PPI-SF’s CN) showed good support of unidimensionality. One-factor models were fit using the diagonally weighted least squares estimator in the “lavaan” package (Rosseel, 2012). Goodness of fit was assessed using comparative fit index (Bentler, 1990), Tucker-Lewis index (Tucker & Lewis, 1973), and root-mean-square error of approximation index (Steiger, 1990). With the exception of three factors (LSRP’s SP, ANT-E, and PPI-SF’s CN), all factors achieved good fit on at least two of the fit indices. Subsequent IRT analyses were conducted separately for each of the factors in the corresponding instrument. Adopting a conservative approach, we refrained from conducting IRT analyses on the subscales that did not meet the unidimensionality criteria. IRT results for ANT-E and PPI-SF’s CN are included in the supplementary material (Appendix 1, Tables 2, and 3) for references only. However, IRT results for LSRP’s SP are presented for comparison with LSRP’s PP.

Table 2.

Results From PCA and CFA Each of the Four Self-Report Measures of Psychopathy

| Scale | λ1 | λ2 | λ3 | UNIDI | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | WRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSRP | ||||||||

| Primary psychopathy | 5.05 | 1.42 | .98 | 8.16 | .97 | .96 | .07 | 2.07 |

| Secondary psychopathy | 2.36 | 1.33 | 1.09 | 4.11 | .83 | .77 | .13 | 2.91 |

| PAI ANT | ||||||||

| Antisocial behavior | 3.14 | 1.08 | .85 | 8.88 | .96 | .90 | .10 | 3.15 |

| Egocentricity | 2.53 | 1.28 | .95 | 3.90 | .91 | .88 | .13 | 2.82 |

| Stimulus seeking | 3.32 | 1.10 | .84 | 8.45 | .99 | .99 | .06 | 1.49 |

| PPI-SF | ||||||||

| Blame externalization | 3.41 | .78 | .75 | 76.78 | .99 | .99 | .08 | 1.61 |

| Social potency | 3.15 | .93 | .75 | 12.36 | .97 | .96 | .12 | 2.38 |

| Machiavellian | 2.54 | .97 | .93 | 36.17 | .97 | .96 | .07 | 1.50 |

| Fearlessness | 2.95 | .96 | .74 | 9.06 | .99 | .99 | .05 | 1.20 |

| Coldheartedness | 2.03 | 1.06 | .96 | 9.78 | .93 | .90 | .07 | 1.50 |

| Impulsive nonconformity | 2.33 | 1.06 | .97 | 13.78 | .94 | .91 | .08 | 1.75 |

| Stress immunity | 3.15 | .83 | .79 | 68.00 | .99 | .99 | .05 | 1.13 |

| Carefree nonplanfulness | 2.26 | 1.25 | .95 | 3.46 | .88 | .81 | .14 | 2.92 |

| SRP-II | ||||||||

| Interpersonal | 4.92 | 1.45 | 1.10 | 9.73 | .96 | .95 | .08 | 2.06 |

| Disinhibition/Impulsivity | 3.30 | .98 | .96 | 139.75 | .99 | .99 | .05 | 1.08 |

| Fearlessness | 2.21 | .86 | .84 | 64.91 | .99 | .99 | .06 | .75 |

| Coldheartedness | 2.74 | .86 | .75 | 17.30 | 1.00 | .99 | .05 | .82 |

Note. λ1, λ2, λ3 = first three eigenvalues of the polychoric correlation matrix from principal component analyses (PCAs); UNIDI = UNIDI index, where UNIDI index > 5 shows good support of unidimensionality (Martínez Arias, 1995, p. 297); CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation; WRMR = weighted root-mean-square residual; LSRP = Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale; PAI ANT = Personality Assessment Inventory—Antisocial Features Scale; PPI-SF = Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Short Form; SRP-II = Self-Report Psychopathy Scale-II.

Estimated Item Parameters

LSRP

Item parameters for the LSRP were estimated separately for the PP and SP factors (see Table 3). Items assessing primary psychopathy had, on average, higher α parameters, than those assessing secondary psychopathy (U = 120, p = .007). The higher α parameters in the PP factor suggest that primary psychopathy features are more discriminating than characteristics associated with secondary psychopathy. That is, items assessing primary psychopathy features are better at differentiating between individuals with varying levels of psychopathic traits than items measuring secondary psychopathy features. Items in the PP factor had, on average, higher β parameters than those in the SP factor (U = 118, p = .008; U = 119, p = .007; U = 133, p < .001, for β1, β2, and β3, respectively). With higher category thresholds, items assessing primary psychopathy are rarely endorsed, especially among individuals with lower levels of the latent trait. On the other hand, items tapping secondary psychopathy are frequently endorsed even among respondents with low levels of the latent trait.

Table 3.

LSRP Estimated Parameters From GRM

| Factor | Item | α | β1 | β2 | β3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary psychopathy | 1 | 1.14 (.07) | −1.24 (.08) | .36 (.07) | 2.53 (.11) |

| 2 | 2.74 (.17) | .46 (.12) | 2.99 (.17) | 5.53 (.27) | |

| 3 | 2.62 (.16) | .02 (.11) | 2.48 (.15) | 5.14 (.25) | |

| 4 | 1.71 (.11) | .23 (.09) | 1.88 (.11) | 3.75 (.16) | |

| 5 | 1.16 (.08) | −.94 (.08) | .34 (.07) | 2.74 (.12) | |

| 6 | 1.16 (.08) | −.26 (.07) | 1.43 (.08) | 3.33 (.14) | |

| 7 | 1.25 (.08) | −.20 (.07) | 1.58 (.09) | 3.39 (.14) | |

| 8 | 1.12 (.07) | −1.24 (.08) | .18 (.07) | 2.32 (.10) | |

| 9 | 1.68 (.10) | −.47 (.09) | 1.55 (.10) | 4.14 (.18) | |

| 10 | .87 (.07) | −.17 (.07) | 1.47 (.08) | 3.07 (.13) | |

| 11 | 1.12 (.08) | −.38 (.07) | .96 (.08) | 2.66 (.11) | |

| 12 | 1.05 (.08) | −.68 (.07) | 2.38 (.11) | 3.50 (.15) | |

| 13 | 1.56 (.11) | 1.39 (.10) | 2.85 (.14) | 4.22 (.20) | |

| 14 | 1.12 (.09) | 1.11 (.08) | 2.37 (.11) | 3.57 (.16) | |

| 15 | 1.03 (.08) | −.23 (.07) | 1.33 (.08) | 3.18 (.13) | |

| 16 | 1.06 (.08) | .23 (.07) | 1.59 (.09) | 3.37 (.14) | |

| AIC = 41,826; BIC = 42,155 (Chi-square test not available) | |||||

|

| |||||

| 18 | .72 (.08) | −1.93 (.09) | −.52 (.07) | 1.17 (.07) | |

| Secondary psychopathy | 19 | .56 (.08) | −.76 (.07) | 1.25 (.07) | 2.86 (.12) |

| 20 | .88 (.10) | −1.29 (.08) | .20 (.07) | 1.99 (.10) | |

| 21 | 1.39 (.15) | −1.84 (.12) | .44 (.08) | 2.68 (.16) | |

| 22 | .91 (.08) | −.93 (.07) | .57 (.07) | 2.26 (.10) | |

| 23 | .63 (.08) | −1.10 (.07) | 1.02 (.07) | 2.65 (.11) | |

| 24 | 1.01 (.14) | −.79 (.08) | .62 (.07) | 2.17 (.12) | |

| 25 | 1.17 (.15) | −.78 (.08) | .65 (.08) | 2.39 (.14) | |

| 26 | .73 (.08) | .24 (.06) | 1.26 (.08) | 2.53 (.11) | |

| AIC = 28,151; BIC = 28,346; χ2 (26,1624) = 24,361, p = 1.00 | |||||

Note. α = estimated slope parameters; β1, β2, and β3 = estimated category threshold parameters. Standard errors of the estimated parameters are presented in parentheses.

PAI ANT

Two GRMs were performed to estimate the item parameters for the ANT-A and ANT-S factors of the PAI (see Table 4). There were no differences in the averaged item parameters between different factors, H (1) = 0.04, p = .83; H (1) = 0.89, p = .34; H (1) = 0.54, p = .46; H (1) = 1.10, p = .29, for α, β1, β2, and β3, respectively. Results suggest that the PAI ANT items in the two factors are similar at differentiating individuals with different levels of latent trait traits, with similar frequencies at which the items are endorsed.

Table 4.

PAI ANT Estimated Parameters From GRM

| Factor | Item | α | β1 | β2 | β3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antisocial behavior | 1 | 1.25 (.10) | .23 (.07) | 2.12 (.11) | 4.04 (.19) |

| 2 | 1.65 (.12) | .41 (.09) | 2.16 (.12) | 3.07 (.15) | |

| 3 | 1.83 (.12) | −2.70 (.14) | .12 (.09) | 1.19 (.10) | |

| 4 | 1.29 (.09) | −1.27 (.09) | 1.10 (.08) | 2.14 (.10) | |

| 5 | 1.21 (.09) | −.49 (.07) | 1.73 (.09) | 2.94 (.13) | |

| 6 | 1.22 (.11) | 1.60 (.10) | 1.87 (.11) | 2.19 (.12) | |

| 7 | 1.33 (.10) | .57 (.08) | 1.20 (.09) | 1.93 (.10) | |

| 8 | 1.42 (.10) | −.03 (.08) | .78 (.08) | 1.79 (.10) | |

| AIC = 20,637; BIC = 10,801; χ2 (65,373) = 12,468, p = 1.00 | |||||

|

| |||||

| Stimulus seeking | 17 | 3.07 (.18) | −.27 (.12) | 3.24 (.19) | 5.13 (.26) |

| 18 | 5.96 (.70) | −.73 (.23) | 4.96 (.57) | 8.48 (.91) | |

| 19 | 2.07 (.12) | −.84 (.10) | 1.92 (.12) | 3.42 (.16) | |

| 20 | .73 (.07) | .37 (.07) | 1.80 (.09) | 2.97 (.13) | |

| 21 | .70 (.08) | 1.16 (.07) | 2.20 (.10) | 3.01 (.13) | |

| 22 | .82 (.07) | −2.00 (.09) | −.21 (.07) | .94 (.07) | |

| 23 | 1.44 (.09) | −.53 (.08) | 1.70 (.10) | 3.31 (.14) | |

| 24 | 1.15 (.08) | −2.37 (.11) | −1.04 (.08) | .98 (.08) | |

| AIC = 20,665; BIC = 20,830; χ2 (65,379) = 10,410, p = 1.00 | |||||

Note. α = estimated slope parameters; β1, β2, and β3 = estimated category threshold parameters. Standard errors of the estimated parameters are presented in parentheses. Results for the egocentricity subscale is not available as the subscale did not meet the unidimensional assumption for IRT analyses.

PPI-SF

The estimated item parameters of the eight factors in the PPI-SF are presented in Table 5. On average, the estimated α parameters vary across the seven factors, H (6) = 15.05, p = .02. The α parameters were higher for items loading on BE and SP than those on ME, C, and IN; items in the SI and F factors had higher α parameters than those in the C factor. There were also differences in the estimated β parameters across the eight factors, H (6) = 28.47, p < .001; H (6) = 29.86, p < .001; H (6) = 23.64, p < .001, for β1, β2, and β3, respectively. Items in the SP and SI factors had, on average, lower β1 parameters, indicating lower category thresholds, than items in the other factors. On the other hand, items in the C and ME factors had, on average, higher β3 parameters, than those in the other factors. Taken together, results suggest that social potency and stress immunity features are frequently endorsed, whereas characteristics indicative of coldheartedness and Machiavellian are rarely endorsed among these participants.

Table 5.

PPI-SF Estimated Parameters From GRM

| Factor | Item | α | β1 | β2 | β3 | Factor | Item | α | β1 | β2 | β3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blame externalization | 1 | 2.63 (.17) | −1.60 (.13) | 2.27 (.15) | 4.49 (.23) | Coldheartedness | 1 | 1.09 (.11) | −.31 (.07) | 1.90 (.10) | 3.92 (.19) |

| 2 | 2.73 (.17) | −1.99 (.14) | 2.12 (.15) | 4.47 (.23) | 2 | 1.25 (.12) | .54 (.08) | 2.69 (.13) | 3.93 (.19) | ||

| 3 | 1.90 (.12) | −.55 (.09) | 2.13 (.12) | 3.69 (.17) | 3 | 1.20 (.11) | −.67 (.08) | 1.90 (.10) | 3.77 (.18) | ||

| 4 | 1.11 (.08) | −1.18 (.08) | 1.20 (.08) | 2.49 (.11) | 4 | 1.12 (.11) | .49 (.07) | 2.19 (.11) | 3.66 (.17) | ||

| 5 | 1.44 (.09) | −.47 (.08) | 1.25 (.09) | 2.49 (.11) | 5 | .45 (.07) | −.92 (.07) | .92 (.07) | 2.35 (.10) | ||

| 6 | 1.58 (.09) | −1.62 (.10) | 1.32 (.09) | 3.06 (.13) | 6 | 1.03 (.10) | −.92 (.08) | 1.26 (.08) | 3.16 (.14) | ||

| 7 | 1.32 (.08) | −2.20 (.10) | .53 (.08) | 2.21 (.10) | 7 | .52 (.08) | −2.27 (.10) | −1.00 (.07) | .48 (.06) | ||

| AIC = 19,278; BIC = 19,422; χ2 (16,286) = 8,144, p = 1.00 | AIC = 19,543; BIC = 19687; χ2 (16,304) = 7,838, p = 1.00 | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Social potency | 1 | 1.59 (.11) | −5.21 (.27) | −3.00 (.14) | .62 (.08) | Impulsive nonconformity | 1 | 1.04 (.10) | −.07 (.07) | 1.98 (.10) | 3.49 (.16) |

| 2 | 1.70 (.11) | −3.51 (.16) | −.99 (.09) | 1.66 (.10) | 2 | 1.19 (.10) | −1.11 (.08) | 1.32 (.09) | 2.95 (.14) | ||

| 3 | 1.64 (.11) | −3.23 (.15) | −.70 (.09) | 1.85 (.11) | 3 | 1.16 (.09) | −1.50 (.09) | .79 (.08) | 2.87 (.13) | ||

| 4 | 1.79 (.11) | −2.68 (.13) | −.77 (.09) | 1.49 (.10) | 4 | 1.36 (.11) | −1.52 (.10) | .76 (.08) | 2.79 (.13) | ||

| 5 | 1.90 (.12) | −3.19 (.15) | −1.26 (.10) | 1.18 (.10) | 5 | 1.26 (.12) | .59 (.08) | 1.89 (.11) | 3.29 (.16) | ||

| 6 | 1.27 (.09) | −3.34 (.14) | −1.05 (.08) | 1.46 (.09) | 6 | 1.13 (.11) | .47 (.07) | 1.52 (.09) | 2.45 (.12) | ||

| 7 | 1.10 (.08) | −2.55 (.11) | −.85 (.08) | 1.43 (.08) | 7 | .37 (.07) | −1.24 (.07) | .57 (.06) | 2.00 (.09) | ||

| AIC = 19,734; BIC = 19,878; χ 2 (16,291) = 7,339, p = 1.00 | AIC = 20,169; BIC = 20,313; χ 2 (16,291) = 10,264, p = 1.00 | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Machiavellian | 1 | 1.94 (.14) | −2.08 (.13) | 1.19 (.10) | 3.67 (.19) | Stress immunity | 1 | 1.89 (.11) | −1.97 (.11) | −.10 (.09) | 2.66 (.13) |

| 2 | 1.84 (.13) | −1.30 (.10) | 1.54 (.11) | 3.70 (.18) | 2 | 2.33 (.14) | −3.44 (.17) | −.78 (.11) | 2.65 (.15) | ||

| 3 | .88 (.08) | −1.51 (.08) | .72 (.07) | 2.83 (.12) | 3 | 2.16 (.13) | −4.22 (.20) | −1.36 (.11) | 2.10 (.13) | ||

| 4 | .68 (.07) | −2.08 (.09) | −.17 (.06) | 2.03 (.09) | 4 | 1.26 (.08) | −2.27 (.10) | −.38 (.07) | 1.85 (.09) | ||

| 5 | .99 (.09) | .11 (.07) | 1.89 (.09) | 3.37 (.15) | 5 | 1.47 (.09) | −3.41 (.15) | −1.40 (.09) | 1.42 (.09) | ||

| 6 | 1.08 (.08) | −1.31 (.08) | 1.21 (.08) | 2.70 (.12) | 6 | 1.07 (.07) | −2.02 (.09) | −.17 (.07) | 1.84 (.09) | ||

| 7 | 1.23 (.09) | −1.57 (.09) | .97 (.08) | 3.23 (.14) | 7 | 1.02 (.07) | −.96 (.07) | .85 (.07) | 2.88 (.12) | ||

| AIC = 20,255; BIC = 20,399; χ 2 (16,281) = 7,937, p = 1.00 | AIC = 20,422; BIC = 20,566; χ 2 (16,286) = 8,088, p = 1.00 | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Fearlessness | 1 | .93 (.07) | −.82 (.07) | .14 (.07) | 1.45 (.08) | ||||||

| 2 | 2.06 (.14) | −.65 (.10) | .82 (.10) | 2.74 (.15) | |||||||

| 3 | 1.52 (.10) | −.93 (.09) | .23 (.08) | 1.76 (.10) | |||||||

| 4 | 1.21 (.09) | −.01 (.07) | 1.16 (.08) | 2.57 (.12) | |||||||

| 5 | 1.47 (.10) | −1.33 (.09) | −.01 (.08) | 1.60 (.09) | |||||||

| 6 | 1.90 (.13) | −.61 (.09) | .61 (.09) | 1.82 (.11) | |||||||

| 7 | 1.09 (.08) | −1.01 (.08) | .73 (.07) | 2.57 (.11) | |||||||

| AIC = 21,691; BIC = 21,835; χ 2 (16,330) = 14,900, p = 1.00 | |||||||||||

Note. α = estimated slope parameters; β1, β2, and β3 = estimated category threshold parameters. Standard errors of the estimated parameters are presented in parentheses. Results for the carefree nonplanfulness subscale is not available as the subscale did not meet the unidimensional assumption for IRT analyses.

SRP-II

The estimated item parameters of the four factors in the SRP-II are presented in Table 6. As the SRP-II items consist of seven response categories, six β parameters were estimated to indicate the threshold for each transition between response categories. There were no differences between items from different factors with respect to the α parameters, H (3) = 4.00, p = .26, suggesting items loaded on different factors are similar in discriminating across individuals with varying trait levels. With respect to the β parameters, there were substantial differences between items loaded on different factors, H (3) = 22.84, p < .001; H (3) = 24.98, p < .001; H (3) = 25.75, p < .001; H (3) = 25.38, p < .001; H (3) = 22.77, p < .001; H (3) = 16.41, p < .001, for β1, β2, β3, β4, β5, and β6, respectively. Items in the C and DI factors had, on average, higher β parameters than those in the IP and F. These findings suggest that coldheartedness and disinhibition/impulsivity features of psychopathy are less frequently endorsed than interpersonal and fearlessness features among participants in this study.

Table 6.

SRP-II Estimated Parameters From GRM

| Factor | Item | α | β1 | β2 | β3 | β4 | β5 | β6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal | 1 | 1.16 (.07) | −3.10 (.13) | −1.93 (.09) | −1.41 (.08) | −.44 (.07) | .99 (.08) | 2.35 (.10) |

| 2 | 1.29 (.08) | −1.06 (.08) | −.11 (.07) | .44 (.07) | 1.37 (.08) | 2.25 (.10) | 3.28 (.14) | |

| 3 | 2.10 (.11) | −3.19 (.15) | −1.96 (.11) | R1.16 (.10) | .04 (.09) | 2.02 (.12) | 3.75 (.16) | |

| 4 | 1.38 (.08) | −3.02 (.13) | −1.79 (.10) | −.87 (.08) | .05 (.08) | 1.61 (.10) | 3.07 (.13) | |

| 5 | 1.86 (.10) | −3.08 (.14) | −1.68 (.10) | −.97 (.09) | .15 (.09) | 1.81 (.10) | 3.34 (.14) | |

| 6 | .68 (.06) | −2.98 (.13) | −2.09 (.09) | −1.40 (.08) | −.33 (.06) | .85 (.07) | 2.10 (.09) | |

| 7 | .94 (.07) | −2.56 (.11) | −1.45 (.08) | −.64 (.07) | .20 (.66) | 1.68 (.08) | 2.89 (.12) | |

| 8 | 1.36 (.08) | −2.84 (.12) | −1.80 (.09) | −.86 (.08) | .22 (.08) | 1.52 (.09) | 2.86 (.12) | |

| 9 | .72 (.07) | −2.61 (.11) | −1.66 (.08) | −1.02 (.07) | −.03 (.06) | .89 (.07) | 2.04 (.09) | |

| 10 | .83 (.07) | −2.32 (.10) | −1.46 (.08) | −.77 (.07) | .17 (.07) | 1.30 (.08) | 2.63 (.11) | |

| 11 | 1.11 (.07) | −1.49 (.09) | −.45 (.07) | .18 (.07) | 1.09 (.08) | 2.00 (.10) | 3.08 (.13) | |

| 12 | .69 (.06) | −1.69 (.08) | −.88 (.07) | −.32 (.06) | .77 (.07) | 1.41 (.08) | 2.19 (.10) | |

| 13 | 1.19 (.07) | −1.72 (.09) | −.51 (.07) | .28 (.07) | 1.17 (.08) | 2.07 (.10) | 3.30 (.14) | |

| 14 | 1.31 (.08) | −1.49 (.09) | −.59 (.08) | .03 (.07) | .89 (.08) | 2.20 (.10) | 3.39 (.14) | |

| 15 | .84 (.07) | −1.93 (.09) | −.90 (.07) | −.04 (.07) | .64 (.07) | 1.26 (.08) | 2.43 (.11) | |

| 16 | 1.75 (.09) | −1.95 (.11) | −.55 (.09) | .49 (.09) | 1.58 (.10) | 2.97 (.13) | 4.43 (.19) | |

| AIC = 68,839; BIC = 69,412 (Chi-square test unavailable) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Disinhibition/Impulsivity | 17 | .79 (.07) | −1.07 (.07) | .05 (.06) | .72 (.07) | 1.67 (.08) | 2.75 (.12) | 4.00 (.19) |

| 18 | .67 (.06) | −1.76 (.08) | −.38 (.06) | .79 (.07) | 1.39 (.08) | 2.32 (.10) | 3.26 (.13) | |

| 19 | 1.99 (.12) | .15 (.09) | 1.40 (.11) | 2.06 (.12) | 2.62 (.13) | 3.34 (.15) | 4.16 (.18) | |

| 20 | 1.19 (.08) | −.53 (.07) | .37 (.07) | .84 (.08) | 1.44 (.09) | 2.53 (.11) | 3.43 (.14) | |

| 21 | 1.39 (.10) | .83 (.09) | 1.36 (.09) | 1.68 (.10) | 2.06 (.11) | 2.67 (.12) | 3.28 (.14) | |

| 22 | 4.57 (.44) | 1.75 (.24) | 3.37 (.34) | 4.48 (.41) | 5.81 (.50) | 7.29 (.59) | 8.39 (.67) | |

| 23 | 1.61 (.10) | −.53 (.08) | .67 (.09) | 1.38 (.10) | 2.26 (.11) | 3.30 (.14) | 4.36 (.19) | |

| 24 | 1.56 (.10) | .41 (.09) | 1.22 (.09) | 1.72 (.10) | 2.58 (.12) | 3.58 (.15) | 4.49 (.21) | |

| 25 | 1.44 (.10) | .82 (.09) | 1.41 (.10) | 1.89 (.11) | 2.58 (.12) | 3.31 (.15) | 4.00 (.18) | |

| AIC = 31,527; BIC = 31,849 (Chi-square test unavailable) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Fearlessness | 26 | .76 (.07) | −1.85 (.09) | −1.32 (.08) | −.99 (.07) | −.45 (.07) | .39 (.06) | 1.57 (.08) |

| 27 | 3.10 (.30) | −2.28 (.20) | −.91 (.14) | −.00 (.12) | 1.07 (.15) | 2.69 (.23) | 4.57 (.35) | |

| 28 | 1.35 (.09) | −2.96 (.13) | −1.97 (010) | −1.16 (.08) | −.22 (.08) | 1.16 (.09) | 2.67 (.12) | |

| 29 | 1.05 (.08) | −2.02 (.10) | −1.14 (.08) | −.51 (.07) | .20 (.07) | 1.02 (.08) | 2.15 (.10) | |

| 30 | 1.47 (.10) | −1.24 (.09) | −.17 (.08) | .45 (.08) | 1.24 (.09) | 2.25 (.11) | 3.40 (.15) | |

| AIC = 22,243; BIC = 22,422; χ2 (16725) = 14556, p = 1.00 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Coldheartedness | 31 | 2.42 (.16) | −.76 (.11) | 1.40 (.12) | 2.76 (.16) | 3.90 (.20) | 4.74 (.24) | 5.57 (.28) |

| 32 | 1.90 (.12) | −.51 (.09) | 1.74 (.11) | 2.70 (.14) | 3.60 (.17) | 4.39 (.21) | 5.21 (.25) | |

| 33 | .97 (.07) | −1.21 (.08) | .08 (.07) | .85 (.07) | 1.67 (.09) | 2.58 (.11) | 3.67 (.17) | |

| 34 | 1.35 (.09) | −1.16 (.09) | .21 (.08) | 1.39 (.09) | 2.25 (.11) | 2.94 (.13) | 3.82 (.17) | |

| 35 | 1.90 (.12) | −1.19 (.10) | .69 (.09) | 1.85 (.11) | 2.96 (.15) | 3.73 (.17) | 4.78 (.22) | |

| 36 | 1.35 (.10) | .73 (.08) | 1.59 (.10) | 2.03 (.11) | 3.03 (.14) | 3.72 (.17) | 4.39 (.21) | |

| AIC = 21,131; BIC = 21,346; χ2 (117356) = 11387, p = 1.00 | ||||||||

Note. α = estimated slope parameters; β1, β2, β3, β4, β5, and β6 = estimated category threshold parameters. Standard errors of the estimated parameters are presented in parentheses.

Test Information

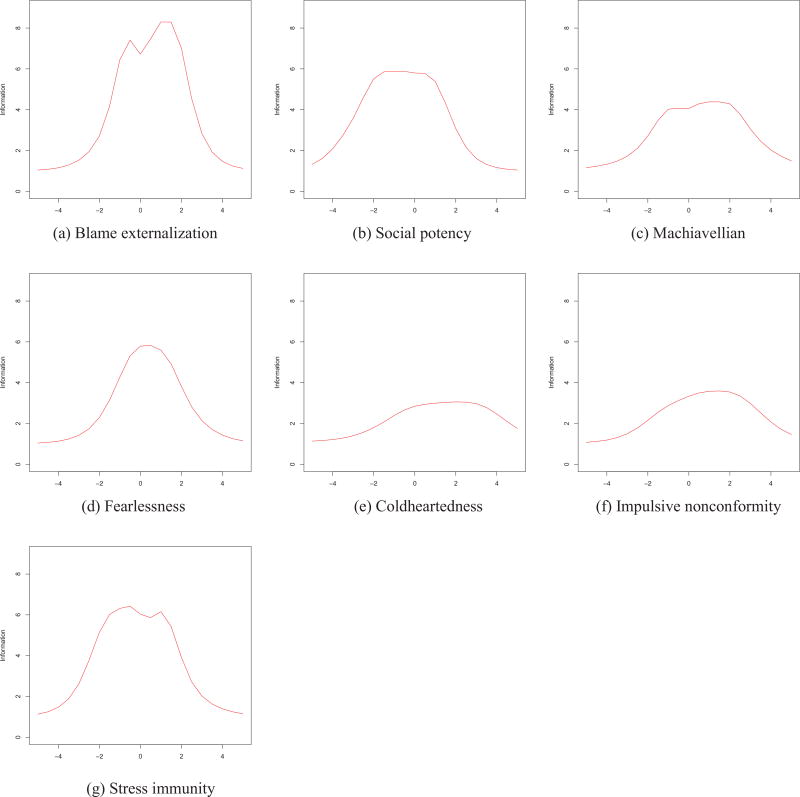

The TIFs of each factor in the four self-report measures of psychopathy across the latent trait continuum are shown in Table 7, and the corresponding TICs are presented in Figures 1 to 4. The TICs reflect the amount of information provided by the subscales across the whole range of the latent trait continuum. The latent trait is estimated with relative precision at the peak of the TIC, where a maximum amount of information is provided by the subscale. A TIC with a narrow peak indicates that the scale is relatively precise around the corresponding latent trait levels, but not as precise at the extremes. On the other hand, a TIC that is smooth and flat indicates that the scale is able to measure respondents across a wide range of latent trait level with similar, albeit less, precision.

Table 7.

Information Functions Across the Latent Trait Continuum

| Information at different levels of latent trait (θ) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Measure | −3.0 | −2.5 | −2.0 | −1.5 | −1.0 | −.5 | 0 | .5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

| LSRP | |||||||||||||

| Primary psychopath | 1.71 | 2.17 | 2.86 | 3.89 | 5.47 | 7.88 | 10.32 | 11.03 | 11.36 | 11.16 | 11.06 | 9.26 | 6.91 |

| Secondary psychopath | 1.88 | 2.20 | 2.55 | 2.88 | 3.09 | 3.21 | 3.27 | 3.30 | 3.28 | 3.25 | 3.17 | 2.95 | 2.63 |

| PAI ANT | |||||||||||||

| Antisocial behavior | 1.44 | 1.85 | 2.47 | 3.14 | 3.76 | 4.45 | 5.16 | 5.56 | 5.53 | 5.15 | 4.50 | 3.68 | 2.91 |

| Stimulus seeking | 1.54 | 1.73 | 2.01 | 2.51 | 3.65 | 9.14 | 13.86 | 10.03 | 14.57 | 14.90 | 6.22 | 3.38 | 2.32 |

| PPI−SF | |||||||||||||

| Blame externalization | 1.52 | 1.94 | 2.70 | 4.17 | 6.44 | 7.41 | 6.72 | 7.47 | 8.30 | 8.29 | 7.02 | 4.56 | 2.83 |

| Social potency | 3.58 | 4.60 | 5.51 | 5.86 | 5.87 | 5.88 | 5.80 | 5.78 | 5.39 | 4.31 | 3.08 | 2.16 | 1.61 |

| Machiavellian | 1.72 | 2.11 | 2.72 | 3.48 | 4.03 | 4.07 | 4.07 | 4.29 | 4.39 | 4.38 | 4.29 | 3.77 | 3.05 |

| Fearlessness | 1.42 | 1.74 | 2.29 | 3.14 | 4.27 | 5.32 | 5.79 | 5.83 | 5.60 | 4.92 | 3.82 | 2.82 | 2.14 |

| Coldheartedness | 1.40 | 1.57 | 1.80 | 2.09 | 2.40 | 2.66 | 2.84 | 2.94 | 3.00 | 3.04 | 3.06 | 3.05 | 2.97 |

| Impulsive nonconformity | 1.50 | 1.78 | 2.16 | 2.55 | 2.88 | 3.13 | 3.34 | 3.50 | 3.58 | 3.60 | 3.54 | 3.35 | 2.98 |

| Stress immunity | 2.61 | 3.77 | 5.14 | 6.02 | 6.32 | 6.42 | 6.03 | 5.86 | 6.16 | 5.44 | 3.92 | 2.72 | 2.02 |

| SRP-II | |||||||||||||

| Interpersonal | 4.12 | 5.44 | 7.02 | 8.33 | 8.99 | 9.20 | 9.19 | 9.09 | 9.07 | 8.95 | 8.44 | 7.27 | 5.81 |

| Disinhibition/Impulsivity | 1.37 | 1.54 | 1.84 | 2.35 | 3.19 | 4.57 | 7.82 | 11.95 | 12.57 | 12.52 | 10.61 | 6.30 | 4.61 |

| Fearlessness | 1.80 | 2.10 | 2.51 | 3.30 | 4.83 | 5.77 | 5.91 | 5.81 | 5.69 | 5.37 | 3.97 | 2.79 | 2.17 |

| Coldheartedness | 1.30 | 1.54 | 1.99 | 2.82 | 4.14 | 5.49 | 6.04 | 6.32 | 6.57 | 6.68 | 6.64 | 6.08 | 4.80 |

Note. LSRP = Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale; PAI ANT: Personality Assessment Inventory—Antisocial Features Scale; PPI-SF = Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Short Form; SRP-II = Self- Report Psychopathy Scale-II.

Figure 1.

Test information curves for LSRP subscales. See the online article for the color version of this figure.

Figure 4.

Test information curves for SRP-II subscales. See the online article for the color version of this figure.

LSRP

The TIFs of the PP factor varied across the latent trait continuum, as reflected in the relatively steep TIC in Figure 1a. Such variation indicates that the primary psychopathy trait is measured with unequal precision at varying latent trait levels. In comparison, the TIC of the SP factor was relatively flat over the range θ = −1 to 1.5 (Figure 1b), suggesting that the latent trait of secondary psychopathy is measured with similar precision within this range, whereas measurement precision decreases outside the range. Overall, the TIFs of the PP factor were higher than those of the SP factor across the latent trait continuum, meaning that the latent primary psychopathy trait is measured with greater precision than characteristics indicative of the latent secondary psychopathy construct.

PAI ANT

As shown in Figure 2a, the TIC of the ANT-A is relatively symmetric around θ = 0.5 to 1.5, suggesting that the latent antisocial behavior trait is estimated with some precision around moderate to moderately high levels of the latent trait. A spike in test information was observed in the TIC for the ANT-S in the range of θ = −1 and 2 (Figure 2b), indicating that relative precise estimation of the stimulus seeking trait may also be limited to individuals with moderate to moderate high levels of stimulus seeking. Of note, the maximum values of TIFs were much higher in the ANT-S than those in the ANT-A, suggesting that the assessment of stimulus seeking is relatively more precise than antisocial behavior.

Figure 2.

Test information curves for PAI ANT subscales. See the online article for the color version of this figure.

PPI-SF

The TICs for the BE and F factors had the highest peaks (Figures 3a and 3d), suggesting that the estimation of these two latent traits are relatively precise, especially within the range of θ = −1.5 to 2.5 and θ = −1 to 1.5, respectively. There are relatively flat TIC peaks for the SP, ME, and SI factors (θ = −2 to 1, θ = −1 to 2, and θ = −2 to 1.5 in Figures 3b, 3c, and 3g, respectively), meaning that the corresponding latent traits are measured with similar precision within these ranges, but decrease rapidly beyond them. In comparison, the TICs of the C and IN factors were relatively flat (Figures 3e and 3f), indicating that these respective latent traits are measured with similar precision. However, the relatively low levels of TIFs indicate that the C and IN factors yield small amount of information, suggesting that these two corresponding traits are estimated with limited precision.

Figure 3.

Test information curves for PPI-SF subscales. See the online article for the color version of this figure.

SRP-II

The TIC of the DI factor showed a tall, narrow peak between θ = 0 and 2 (Figure 4b), indicating that this latent trait is measured very precisely within this range of the disinhibition/impulsivity trait continuum. Beyond this narrow range, measurement precision of the disinhibition/impulsivity trait decreases markedly. As for the IP, F, and C factors, the TICs are relatively flat over θ = −1.5 to 2, θ = −1 to 1.5, and θ = −0.5 to 2.5, respectively (Figures 4a, 4c, and 4d). Results suggest that these respective latent traits are measured with similar precision within the flat TIC ranges, and decrease as the TIC slopes decrease toward both ends of the corresponding latent trait continuums.

Comparison Among Measures

Of the 1,257 participants in this study, 1,065 respondents completed all four self-report measures of psychopathy with no missing data. For these participants, two estimates of the latent trait underlying each subscale were available: the total score (Ts) and the estimate from the GRM (θs). We used these estimates to examine the extent to which the factors are associated with one another. In Table 8, the correlation coefficients among Ts (rT) are presented in the lower diagonal, and those among θs (rθ) are displayed in the upper diagonal.

Table 8.

Correlation Matrix of Total Scores and Estimated Latent Traits (θ) Between Subscales of Self-Report Measures of Psychopathy

| LSRP | PAI | PPI-SF | SRP-II | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| PP | SP | ANT-A | ANT-S | BE | SP | ME | F | C | IN | SI | IP | DI | F | C | |

| LSRP | |||||||||||||||

| PP | .42*** | .49*** | .45*** | .30*** | .03 | .59*** | .21*** | .24*** | .22*** | .00 | .59*** | .54*** | .37*** | .55*** | |

| SP | .43*** | .44*** | .38*** | .37*** | −.05 | .42*** | .14*** | .03 | .33*** | −.20*** | .36*** | .47*** | .28*** | .33*** | |

| PAI | |||||||||||||||

| ANT-A | .49*** | .44*** | .59*** | .28*** | .09** | .50*** | .31*** | .14*** | .40*** | .05 | .48*** | .62*** | .45*** | .38*** | |

| ANT-S | .46*** | .44*** | .56*** | .22*** | .20*** | .34*** | .59*** | .12*** | .47*** | .14*** | .45*** | .52*** | .71*** | .30*** | |

| PPI-SF | |||||||||||||||

| BE | .31*** | .39*** | .31*** | .25*** | −.03 | .32*** | .06 | −.06* | .24*** | −.19*** | .26*** | .19*** | .16*** | .17*** | |

| SP | .04 | −.06 | .09** | .20*** | −.05 | .02 | .13*** | .00 | .01 | .23*** | .14*** | .09** | .22*** | .01 | |

| ME | .56*** | .40*** | .45*** | .32*** | .35*** | −.01 | .11*** | .09** | .27*** | −.12*** | .52*** | .43*** | .27*** | .37*** | |

| F | .20*** | .15 | .30*** | .58*** | .06* | .13*** | .09** | .12*** | .42*** | .27*** | .24*** | .29*** | .58*** | .13*** | |

| C | .21*** | .00 | .11*** | .11*** | −.10*** | .06* | .01 | .07* | .09** | .32*** | .20*** | .22*** | .09** | .40*** | |

| IN | .18*** | .30*** | .36*** | .46*** | .22*** | .02 | .15*** | .43*** | .08* | .05 | .30*** | .40*** | .36*** | .23*** | |

| SI | .03 | −.18** | .06* | .15*** | −.21*** | .24*** | −.16*** | .27*** | .35*** | .13*** | .16*** | .03 | .18*** | .09** | |

| SRP-II | |||||||||||||||

| IP | .57*** | .34*** | .45*** | .44*** | .28*** | .15*** | .48*** | .25*** | .16*** | .24*** | .16*** | .41*** | .49*** | .35*** | |

| DI | .54*** | .47*** | .61*** | .52*** | .20*** | .10** | .39*** | .26*** | .20*** | .37*** | .05 | .38*** | .42*** | .61*** | |

| F | .33*** | .27*** | .40*** | .69*** | .17*** | .22*** | .20*** | .58*** | .08* | .33*** | .22*** | .48*** | .03*** | .19*** | |

| C | .54*** | .32*** | .38*** | .30*** | .17*** | .04 | .36*** | .13*** | .33*** | .21*** | .11*** | .32*** | .62*** | .15*** | |

Note. Correlation coefficients between total scores (rT) are presented in the lower diagonal; correlation coefficients between estimated underlying latent traits (rθ) are presented in the upper diagonal. Bolded values indicate significant differences between rT and rθ. LSRP = Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale; PP = Primary Psychopathy; SP = Secondary Psychopathy; PAI = Personality Assessment Inventory; ANT-A = Antisocial Features Scale, Antisocial Behavior; ANT-S = Antisocial Features Scale, Stimulus Seeking; PPI = Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Short Form; BE = Blame Externalization; SP = Social Potency; ME = Machiavellian; F = Fearlessness; C = Coldheartedness; IN = Impulsive Nonconformity; SI = Stress Immunity; SRP-II = Self-Report Psychopathy Scale-II; IP = Interpersonal; DI = Disinhibition/Impulsivity.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The two factors in the LSRP were moderately correlated with each other (rT = .43; rθ = .42). The correlations among the two PAI ANT factors were moderate (rT = .56; rθ = .59). Among the seven PPI-SF factors, the associations varied (rs = −.19 to .43), suggesting that some of the factors may not be tapping the same underlying construct of psychopathy as the others. Most of the correlations among the SRP-SF factors were moderate to strong (rs = .32 to .61), with the exception of the weak association between F and C.

There are some noteworthy associations between the four self-report measures. For example, LSRP PP is strongly associated with PPI-SF ME, SRP-II IP, SRP-II DI, and SRP-II C (rs = .54 to .60), suggesting that these features may be indicative of primary psychopathy. Participants who endorsed positively on ANT-S also had high levels of F and DI on the SRP-II (rs = .40 to .62). The moderate to strong correlations between ANT-A, PPI-SF IN, and SRP-II DI (rs = .36 to .62) suggest that antisocial behavior endorsed by these respondents may mostly be impulsive actions. The F and C factors in the PPI-SF are moderately associated with the corresponding SRP-II factors (rs = .33 to .58), indicating that there are some differences in the latent traits measured by the PPI-SF and SRP-II items.

Inspection of Table 8 reveals that the directions of the associations among factors are the same between the Ts and the θs. However, there are differences in the correlation magnitudes between some factors. Fisher’s z tests were used to compare the two correlation coefficients (rT and rθ); significant differences are illustrated in bold in Table 8. Such differences suggest that the associations between sum scores (rT) may not represent the relations between underlying latent traits (rθ) estimated by different factors.

Discussion

The current study investigated how well the latent construct of psychopathy is measured among a large undergraduate sample, in which the levels of psychopathy are presumably quite low. The LSRP, PPI-SF, PAI ANT, and the SRP-II were initially developed to assess the underlying psychopathy construct by tapping different components of the latent psychopathy trait. Although it has been argued that these measures are best suited for nonforensic community samples, this is the first study to investigate and compare how well these self-report items assess the varying dimensions of the psychopathy construct among undergraduate students using IRT models.

Overall, items in the LSRP PP factor were moderately to highly discriminating (all αs > .8; Baker, 2001), suggesting that LSRP items indicative of primary psychopathy features (e.g., emotional detachment, selfishness, manipulativeness) are relatively good at distinguishing among individuals with varying levels of the latent primary psychopathy trait. The PP factor showed high levels of test information at moderate to moderately high levels of the latent trait, indicating that the latent primary psychopathy trait is estimated with relative precision among individuals with moderate to moderately high levels of the trait.

On the other hand, five out of the nine LSRP SP items (Items 20, 21, 22, 24, and 25) were at least moderately discriminating, suggesting that some of the SP items may not be sensitive enough to distinguish individuals with different levels of the latent secondary psychopathy trait. The general low levels of information provided by the SP factor suggest that the underlying trait of secondary psychopathy is estimated with limited precision among undergraduate students in the current study.

One possible explanation is that behavior identified to be characteristic of secondary psychopathy (e.g., impulsivity and antisocial behavior) is normative behavior among young adults, and thus are heavily endorsed by normal college students. It is possible that these behavioral characteristics are not particularly sensitive in distinguishing among individuals with varying levels of secondary psychopathy, especially among college students who may endorse these behaviors regardless of their underlying psychopathic tendencies. Taken together, it is questionable whether the LSRP SP factor is an informative measure of secondary psychopathy traits within an undergraduate student sample such as the current one.

Results showed moderate to high discrimination ability for the items in the PAI ANT (all αs > 1.21 for ANT-A; all αs > .70 for ANT-S). The frequencies at which items are endorsed are relatively similar between the two factors, suggesting that the PAI ANT items are informative in the assessment of their respective underlying traits within similar trait levels. However, the two PAI ANT factors estimate their respective latent trait levels with differing degrees of precision, even within the trait range at which the amount of test information is at maximum. The general level of the TIF is the highest for ANT-S, suggesting that the latent trait is estimated with relative precision across varying levels of stimulus seeking trait. This corresponds to the observation that ANT-S contains some of the most discriminating items measuring thrill-pursuing behavior (e.g., Items 17 and 18). The low general TIF level for ANT-A indicates that the items may not be as precise in assessing the construct of social deviance among individuals with different levels of antisocial behavior. In fact, many of the behavior assessed in ANT-A may be normative adolescent behavior (e.g., Items 3 and 4), which the majority of the college students in this study may have endorsed in the past.

Given that the seven factors in the PPI-SF were developed to tap different aspects of the latent psychopathy construct, results revealing differences in item discrimination and category threshold levels suggest that the factors vary in their ability to assess their respective underlying latent traits. With higher discrimination, the BE and SP factors are more effective in distinguishing among respondents who differ in their respective trait levels; the C factor is less effective in doing so as it showed lower discrimination. The items in the SP and SI factors are more frequently endorsed, whereas those in the CN and C are less frequently endorsed. The TIC graphs show that the PPI-SF factors are informative at varying levels along their corresponding latent trait continuums, meaning that the respective latent traits are estimated with different degrees of precision. Across the PPI-SF factors, the PPI-SF C factor, with all reverse-scored items, had the smallest TIFs, indicating that the coldheartedness construct is estimated with relatively low accuracy.

These findings have theoretical implications. Assuming that the latent construct of psychopathy is made up of the eight dimensions assessed by the PPI-SF factors, the current results indicate that some components (e.g., blame externalization, social potency) may be more effective in distinguishing individuals who differ in the latent trait levels. At best, the subscales were only moderately correlated with each other, providing further evidence that the PPI-SF is a multidimensional measure of psychopathy. In addition, extending the current study of the PPI-SF to forensic and other nonforensic samples may help delineate why differential correlates between the PPI-SF subscales in offenders (Neumann, Malterer, & Newman, 2008) and college students (Lilienfeld, 1990) were previously reported. With the development of the revised versions of the PPI and PPI-SF, the PPI-R (Lilienfeld & Widows, 2005) and the PPI-R-40 (Eisenbarth, Lilienfeld, & Yarkoni, 2015), further research is needed to examine the item properties of these revised measures, and whether the items in different subscales vary in their ability to assess the different components of psychopathy.

Items in the four SRP-II factors have similar ability to distinguish among respondents with different levels of the respective latent traits. Results provide some evidence that the rationally derived four factors for the SRP-II (Lester et al., 2013) are equally good at discriminating across individuals with different levels of the respective latent traits. Items in the IP and F factors are more frequently endorsed than those in the C and DI factors, indicating that some features (e.g., coldheartedness) of the psychopathy construct may be rarely endorsed among college students. With the exception of the weak association between the C and F factors, the moderate to strong correlations between the SRP-II factors suggest relative uniformity in factor associations.

There is evidence to suggest that some components of the psychopathy construct are more associated with each other. For example, respondents who were estimated to have high levels of primary psychopathy (in the LSRP) also had high tendencies of psychopathic features such as egocentricity (in the PAI ANT), Machiavellian (in the PPI-SF), interpersonal (in the SRP-II), and coldheartedness (in the SRP-II). The latent trait of stimulus seeking (in the PAI ANT) is associated with characteristics of fearlessness and disinhibition/impulsivity (both in the SRP-II), suggesting that individuals who are fearless and impulsive may be more likely to pursue activities that give them excitement or “thrills.” Likewise, features of impulsive nonconformity (in the PPI-SF) and disinhibition/impulsivity (in the SRP-II) may be strongly associated with the possibly of engaging in social deviant behavior (in the PAI ANT). Two latent traits, fearlessness and coldheartedness, are both measured in the PPI-SF and the SRP-II. The corresponding factors are, at best, moderately correlated. Thus, it is questionable whether the corresponding subscales are tapping the same underlying latent constructs, and whether the estimation of the latent traits can be improved by combining the respective subscales.

Further examination of the estimated item parameters reveals that items’ abilities to measure the underlying latent traits, within each factor, may differ between those that are regular- and reverse-scored. For instance, the negatively worded items in the LSRP SP factor (Item 19: “I find that I am able to pursue one goal for a long time” and Item 23: “Before I do anything, I carefully consider the possible consequences”) are the least discriminating items as compared to the rest of the items in the factor. Our results raised questions as to whether these items are working as they intended to be. The only reverse-scored item in the PPI-SF IN factor (“Fitting in and having things in common with other people my age has always been important to me”) is the least discriminating item in the subscale. All items in the PPI-SF C factor are reverse-scored; the absence of empathy characteristics is inferred to represent the latent trait of coldheartedness, yet they are among the ones with the worst discrimination parameters within the PPI-SF. The PPI-SF C factor also had the smallest TIF values among all the factors examined in this study, suggesting that the coldheartedness trait is estimated with little precision.

A regular-scored item measures the presence of the latent trait, with higher scores indicating higher levels of the underlying trait, whereas a reverse-scored is worded negatively, with lower scores representing higher levels of the latent trait. Our finding that these reverse-scored items may have limited ability in distinguishing among respondents with varying levels of the latent trait adds to the growing body of literature reporting problems with negatively worded items in personality assessment (e.g., Crego & Widiger, 2014; Ebesutani et al., 2012; Lindwall et al., 2012; Ray, Frick, Thornton, Steinberg, & Cauffman, 2016; Rodebaugh, Woods, & Heimberg, 2007; Stansbury, Ried, & Velozo, 2006). These results raise two practical questions. First, is the absence of a trait (e.g., empathy) the same as the endorsement of its supposedly opposing trait (e.g., coldheartedness)? As both traits are latent constructs, it is unclear how well the absence of one indicates the presence of the other (Crego & Widiger, 2014). Second, to what extent is the different discrimination ability between regular- and reverse-scored items a method bias? The methodological literature has identified many potential sources of method bias, such as acquiescence and confirmation bias (see Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003 for a review). However, whether the observed difference in the estimated parameters observed between regular- and reverse-scored items in these self-report psychopathy measures is due to method bias or true difference in discrimination ability is not yet known. Considering that many of the items in the self-report psychopathy measures are worded negatively, studies investigating whether the response bias is present between differently keyed items are much warranted to validate the psychometric properties of these instruments.

In addition to the above findings regarding item properties of the four self-reported psychopathy measures, our results showed that two of the subscales (PAI ANT-E and PPI-SF’s CN) were not unidimensional. The lack of unidimensionality suggests that these two subscales may not be assessing one underlying construct (egocentricity and carefree nonplanfulness, respectively). Future studies should further examine the dimensionality of these subscales to determine whether the items in the subscale were assessing one underlying construct, and whether certain items need to be excluded for scale refinement. In the meantime, we recommend caution when interpreting and using composite scores from these two subscales in clinical and research settings.

This study examined the item functioning of four self-report psychopathy measures using an IRT framework, however, several limitations should be noted. The current sample consisted of college students, in which the average levels of psychopathy are likely to be relatively low. It is unclear whether some of the more frequently endorsed features (e.g., impulsiveness, antisocial behavior) are indicative of endorsement of certain psychopathic components or reflect normative young adult behavior. In addition, some of the items may have different meanings for college students versus adults in the community and/or criminal justice-involved individuals and whether this possibility exists needs further examination. Replication of this study in offender samples is much needed, and future studies should consider examining the item-level psychometric properties of these self-report measures using forensic and prison samples. Nonetheless, it should be noted that we identified some items with good discriminating parameters (e.g., Item 18 in PAI ANT: “Engage in wild activities for fun;” Item 31 in SRP-II: “Not hurting others’ feelings is important to me”), which suggests that some items are able to distinguish respondents with different trait levels, even at the lower end of the trait continuums.

In conclusion, the current study provides some insight concerning the statements developed to assess different components of the psychopathy construct among a large college sample, in which the average levels of psychopathy are assumed to be lower than those among forensic and offending respondents. Results from the IRT analyses suggest that the factors in the four self-report psychopathy instruments differ in their ability to measure the respective latent traits. Considering that the factors were developed to assess various psychopathy dimensions, different factors within each instrument may actually complement each other by providing information at across different latent trait ranges. Our findings reveal that, although some of the latent constructs assessed by the different factors are correlated with one another, none of the associations are exceptionally strong, suggesting that the instruments may be measuring different but related domains of psychopathy. Thus, it appears that the construct of psychopathy may be best conceptualized as a multidimensional construct. In practice, clinicians and researchers may wish to use multiple measures in order to best tap the broader concept of psychopathy. In addition to the total scores of the self-report psychopathy measures, individual factor scores should be used to better understand how the different dimensions of psychopathy is associated with one another.

Supplementary Material

Public Significance Statement.

This study examines the item properties of 4 self-report measures of psychopathy among college students, with results showing that the factors in the instruments differ in their ability to measure the respective latent traits. Findings suggest that multiple measures should be used to tap the multidimensional concept of psychopathy, and raise concerns regarding the use of negatively worded items to assess certain aspects of psychopathy.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by the research training grant 5-T32-MH 13043 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Due to technical error, one item measuring secondary psychopathy (Item 17: “I find myself in the same kinds of trouble, time after time”) was not included in this dataset. However, our findings with respect to the LSRP would likely not be different if the missing item had been included.

Contributor Information

Siny Tsang, Department of Epidemiology, Columbia University.

Randall T. Salekin, Department of Psychology, University of Alabama

C. Adam Coffey, Department of Psychology, University of Alabama.

Jennifer Cox, Department of Psychology, University of Alabama.

References

- Andrich D. A rating formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika. 1978;43:561–573. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02293814. [Google Scholar]

- Baker FB. Item response theory: Parameter estimation techniques. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Baker FB. The basics of item response theory. College Park, MD: ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Benning SD, Patrick CJ, Hicks BM, Blonigen DM, Krueger RF. Factor structure of the psychopathic personality inventory: Validity and implications for clinical assessment. Psychological Assessment. 2003;15:340–350. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.3.340. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.15.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benning SD, Patrick CJ, Salekin RT, Leistico AM. Convergent and discriminant validity of psychopathy factors assessed via self-report: A comparison of three instruments. Assessment. 2005;12:270–289. doi: 10.1177/1073191105277110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1073191105277110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt DM, Hare RD, Vitale JE, Newman JP. A multigroup item response theory analysis of the Psychopathy Checklist— Revised. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:155–168. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.2.155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.16.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley CA, Diamond PM, Magaletta PR, Heigel CP. Cross-validation of Levenson’s Psychopathy Scale in a sample of federal female inmates. Assessment. 2008;15:464–482. doi: 10.1177/1073191108319043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1073191108319043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley CA, Schmitt WA, Smith SS, Newman JP. Construct validation of a self-report psychopathy scale: Does Levenson’s self-report psychopathy scale measure the same constructs as Hare’s Psychopathy Checklist-Revised? Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:1021–1038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00178-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cleckley HM. The mask of sanity an attempt to reinterpret the so-called psychopathic personality. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke DJ, Michie C. Refining the construct of psychopathy: Towards a hierarchical model. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:171–188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.13.2.171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crego C, Widiger TA. Psychopathy, DSM–5, and a caution. Personality Disorders. 2014;5:335–347. doi: 10.1037/per0000078. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/per0000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebesutani C, Drescher CF, Reise SP, Heiden L, Hight TL, Damon JD, Young J. The Loneliness Questionnaire-Short Version: An evaluation of reverse-worded and non-reverse-worded items via item response theory. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2012;94:427–437. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2012.662188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2012.662188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens JF, Hart SD, Johnson DW, Johnson JK, Olver ME. Use of the Personality Assessment Inventory to assess psychopathy in offender populations. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:132–139. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edens JF, Poythress NG, Watkins MM. Further validation of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory among offenders: Personality and behavioral correlates. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2001;15:403–415. doi: 10.1521/pedi.15.5.403.19202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/pedi.15.5.403.19202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbarth H, Lilienfeld SO, Yarkoni T. Using a genetic algorithm to abbreviate the Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Revised (PPI-R) Psychological Assessment. 2015;27:194–202. doi: 10.1037/pas0000032. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pas0000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embretson SE. The new rules of measurement. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8:341–349. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.8.4.341. [Google Scholar]

- Embretson SE, Reise SP. Item response theory for psychologists. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gummelt HD, Anestis JC, Carbonell JL. Examining the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale using a graded response model. Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;53:1002–1006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.014. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. A research scale for the assessment of psychopathy in criminal populations. Personality and Individual Differences. 1980;1:111–119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(80)90028-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. The Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised PCL-R. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. The Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised PCL-R. 2. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, Harpur TJ, Hemphill JD. Scoring pamphlet for the Self-Report Psychopathy Scale: SRP-II. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Simon Fraser University; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD, Neumann CS. The role of antisociality in the psychopathy construct: Comment on Skeem and Cooke (2010) Psychological Assessment. 2010;22:446–454. doi: 10.1037/a0013635. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0013635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpur TJ, Hare RD, Hakstian AR. Two-factor conceptualization of psychopathy: Construct validity and assessment implications. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;1:6–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.1.1.6. [Google Scholar]

- Hauck-Filho N, Teixeira MA. Revisiting the psychometric properties of the Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2014;96:459–464. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2013.865196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.865196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpman B. The myth of the psychopathic personality. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1948;104:523–534. doi: 10.1176/ajp.104.9.523. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/ajp.104.9.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey KR, Rogers R, Robinson EV. Self-report measures of psychopathy: What is their role in forensic assessments? Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2014;37:380–391. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10862-014-9475-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lester WS, Salekin RT, Sellbom M. The SRP-II as a rich source of data on the psychopathic personality. Psychological Assessment. 2013;25:32–46. doi: 10.1037/a0029449. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0029449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]