Abstract

The repair of large tracheal segmental defects remains an unsolved problem. The goal of this study is to apply tissue engineering principles for the fabrication of large segmental trachea replacements. Engineered tracheal replacements composed of autologous cells (“neotracheas”) were tested in a New Zealand White rabbit model. Neotracheas were formed in the rabbit neck by wrapping a silicone tube with consecutive layers of skin epithelium, platysma muscle and an engineered cartilage sheet, and allowing the construct to mature for 8–12 weeks. In total, 28 rabbits were implanted and the neotracheas assessed for tissue morphology. In 11 cases, neotracheas deemed sufficiently strong were used to repair segmental tracheal defects. Initially, the success rate of producing structurally sound neotracheas was impeded by physical disruption of the cartilage sheets during animal handling, but by the end of the study, 15 of 18 neotracheas (83.3%) were structurally sound. Of the 15 structurally sound neotracheas, 11 were used for segmental reconstruction and were left in place for up to 21 days. Histological examination showed the presence of variable amounts of viable epithelium, a vascularized platysma flap, and a layer of safranin O-positive cartilage along with evidence of endochondral ossification. Rabbits that had undergone segmental reconstruction showed good tracheal integration, had a viable epithelium with vascular support, and the cartilage was sufficiently strong to maintain a lumen when palpated. The results demonstrated that viable, tri-layered, scaffold-free neotracheas could be constructed from autologous cells and could be integrated into native trachea to repair a segmental defect.

Introduction

Severe damage to the trachea that necessitates replacement is rare, but for patients who have long-segment tracheal stenosis or atresia the outcomes are grim, with a mortality rate of 77% for stenosis patients and a 100% mortality rate for patients with tracheal atresia (abnormally closed or absent trachea). (1) To address this issue, multiple groups have turned to the field of tissue engineering to develop a systematic methodology to produce a functional, living tracheal replacement. The approaches are quite varied, with some groups taking the approach of seeding decellularized tissues, including tracheas, bladders and aortas, to produce functional replacement tissue, while others have turned to synthetic materials, with and without the addition of host cells. (Reviewed by Bogan et. al. (2, 3)) It turns out that several tracheal implant strategies have been used in people, including the first successful use of a decellularized trachea in 2008. (4) However, the use of decellularized organs is limited by availability and multiple studies using this methodology have had mixed results, including both fatalities and the need for multiple follow-up operations (reported by Vogel et al., 2013(5)). To date, there is no reproducible method to fabricate a functional tracheal replacement for large segmental defects.

This laboratory has pioneered the use of a scaffold-free methodology to produce cartilage sheets used to either repair focal defects (6), or for the fabrication of tracheal replacement units, termed “neotracheas” that are used to repair segmental defects. (7, 8) While these neotracheas were shown to be structurally sound, they eventually failed because of the development of a fibrous plug. (8) While the implants failed with respect to air flow, none of the implants failed due to loss of structural integrity, non-integration or as a results of infection. Based on these results, it was hypothesized that an epithelial lining would be required to impede the fibrosis of the engineered construct. The primary goal of this study was to develop a surgical means of producing a pedicled tri-layered engineered neotrachea construct that consisted of an outer cartilage layer, to provide structural support, an intermediate vascular layer, to provide nutrients, and an inner layer of epithelium to inhibit fibrosis. The results of this study show that a viable epithelium-lined tissue engineered neotrachea can be formed with the use of in vitro cartilage fabrication methods in combination with precise surgical methodologies. Over the course of this study, several improvements were made in the expansion and differentiation of chondrocytes and in the surgical approaches used to produce viable, implantable tri-layered neotracheas.

Materials and Methods

Chondrocyte Cell Culture

Chondrocytes were obtained from the ear cartilage of White New Zealand rabbits, as previously described. (9) Briefly, cartilage pieces, ~1 mm3, were sequentially digested with 660 units/mL of testicular hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) for 15 min, in trypsin/EDTA (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 30 min, and overnight in DMEM/FBS containing 580 units/mL collagenase Type II (Worthington Biochemical Corp, Lakewood, NJ), all at 37°C. Chondrocytes were then passed through a 70 μm filter, centrifuged at 690g for 10 min, resuspended in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (lot#1256415, InVitrogen), and plated at 5.7 × 103 cells/cm2. Cells at 80–90% confluence were passaged with trypsin/EDTA and cells at second passage were used to fabricate cartilage sheets.

Cartilage Sheet Fabrication

Cartilage sheets were fabricated as previously described (9), with minor modifications. Briefly, chondrocytes from second passage were typsinized and plated at 1.9 × 106 cells/cm2 into custom stainless steel biochambers consisting of a 4.0 × 4.0 cm upper chamber with a porous (10 μm) base consisting of a porous polyester membrane (PET1009030; Sterlitech, Kent, WA) coated with human fibronectin (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), which suspended the cells above the lower chamber which was either a 100 mm tissue culture plate or a custom cylindrical chamber with sufficient capacity to allow the addition of sufficient medium volume to totally immerse the biochamber (~300 ml). The large container allowed the cells in the upper chamber to be exposed to much more medium, thus avoiding medium depletion, as evinced by yellowing medium.

Cartilage Sheet Assessment

Cartilage samples were quantified for glycosaminoglycan (GAG), collagen and DNA content as described previously(9). Briefly, 3 mm punches were taken, wet weights (WW) obtained, and then digested in 200 μl of 25 μg/ml of papain in 50 mM sodium phosphate, 2 mM cysteine and 2 mM EDTA, pH 6.5 for 3 hr at 65°C. For collagen assays, a 100 μl aliquot of the papain digest was hydrolyzed in 1 mL of 6 N hydrochloric acid at 110°C overnight, opened and evaporated to dryness at 65°C and then resuspended in 200 μl of water. 100 μl of the sample was combined with 100 μl of 0.15 M copper sulfate and 100 μl of 2.5 N sodium hydroxide, incubated for 5 min at 40°C, and then 100 μl of 6% hydrogen peroxide was added and incubated for an additional 10 min at 40°C. 400 ul of 3N sulfuric acid plus 200 ul of 5% p-dimethyl-amino-benzaldehyde were added and the sample incubated at 70 C for 16 min. Triplicate samples were read for absorbance at 492 nm.

For GAG/DNA assays, a 100 μl aliquot of the papain digest (above) was combined with 200 μL of 100 mM sodium hydroxide and incubated for 30 min at room temperature, and then neutralized with 200 μL of 100 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2. Then, 100 μL of 66.7 ng/ml of Hoeschst 33258 in 0.2 M pH 8.0 sodium phosphate buffer was combined with 50 μL of the sample and read, in triplicate, at 340 nm. The same sample was also assessed for GAG content by safranin O absorbance at 536 nm, as described previously. (10)

Surgical Approaches

All animal studies were conducted under an approved protocol of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Washington. All procedures were performed under general anesthesia, which was induced with ketamine hydrochloride (70 mg/Kg) and xylazine (7 mg/Kg) and maintained with 2% isoflurane. A summary of the procedure for fabricating, implanting and conducting the segmental reconstruction operation is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Surgical method for neotrachea formation.

Ear chondrocytes are harvested, expanded and fabricated into sheets (1). A split-thickness skin graft is wrapped around a silicone tube (2) which is wrapped with platysma muscle (3) followed by the cartilage sheet (4A). The construct is allowed to mature in vivo for approximately 3 months (4B) and is then implanted into a segmental defect (5–7). The implant is first freed of excess fibrous material and the ends cut (5A and B). A segment of native trachea is then removed, sutures put in place, the silicon tube removed (6) and sutured into the tracheal defect (7).

Split Thickness Skin Harvest

While under general anesthesia, rabbit skin was shaved dorsally, 1 cc of Marcaine injected sub-cutaneously, and a ~2 cm incision made caudally. Silk retaining sutures were placed at the incision for retraction and a malleable retractor placed under the skin. A dermatome set at 0.0125” was used to harvest an approximately 2 cm × 4 cm piece of skin, which was then placed into sterile saline. The harvest site was ellipsed out and the remaining skin primarily closed with vicryl.

Two-Step Neotrachea Epithelialization

A 2 cm long cervical skin incision is made to expose the pre-laryngeal strap muscles and the trachea. Next, a rectangular-shaped platysmal flap was developed respecting a lateral vascular supply. Silk sutures were placed at the medial-rostral and medial-caudal corners of the flap to facilitate handling. (Figure 2A). The silicone tube was then wrapped with the platysmal flap and secured with vicryl sutures (Figure 2C). In the latter implants, the ends of the silicone tube were first splayed by heating to impede tissue slippage. A cartilage sheet fabricated with autologous chondrocytes (Figure 2D) was then wrapped around the platysma and secured with vicryl sutures wrapped around the construct (Figure 2E). The skin was then closed in layers with interrupted sutures and a running monocryl intradermal suture. At 8 weeks after the initial operation, the neotrachea consisting of platysma and cartilage is exposed and the construct is opened. The split-thickness skin graft was sutured to the silicone tube (Figure 2B) and the neotrachea was re-closed around the skin graft. The trilaminar construct was allowed to mature approximately 4 more weeks in situ.

Figure 2. Neotrachea fabrication in vivo.

The platysma muscle is formed into a pedicled flap and sutured at the lateral edges (A). A split thickness skin graft is sutured to a silicone tube (B) and then covered and sutured with platysma muscle (C). An engineered cartilage sheet (D) is then wrapped around the platysma/skin/silicone tube construct (E), and the wound closed in layers.

One-Step Neotrachea Epithelialization

Using the same surgical approach as in the two-step method, a split-thickness skin graft is wrapped and sutured around the silicone tube prior to being wrapped with platysma muscle. The platysma muscle/skin graft is then wrapped with an autologous cartilage sheet and sutured in place, and the wound closed as described above.

Outer Platysmal Flap

In a subset of 3 rabbits, a one-step epithelialization procedure was performed wherein a cartilage sheet was wrapped around directly onto the skin graft, instead of the skin graft being opposed to the platysma muscle, and the cartilage sheet was then wrapped on the outside with platysma muscle. Several 2–3 mm holes were punched into the cartilage sheets to facilitate vascularization and support of the skin graft.

Segmental Reconstruction

The matured and vascularized neotrachea was approached through a cervical incision. The construct was dissected carefully to maintain the lateral vasculature. The ends of the neotrachea were trimmed and the silicone tube removed. The neotrachea was palpated to assess structural integrity. An approximately 2 cm long segment of the native trachea was then removed. The superior tracheal incision was made between the 2nd and 3rd tracheal ring below the cricoid ring. The rabbit was able to breathe spontaneously through the lower tracheal opening. The neotrachea was then mobilized into the defect over a trimmed 6 mm pediatric t-tube (approximately 3 cm in length). The rostral and caudal ends of the construct were anastomosed to native trachea using 4–0 vicryl sutures. A preliminary study on two rabbits showed that the rabbits could tolerate T-tube implantations without excessive granulation formation or mucous plugging (Data not shown).

Histology

Samples were fixed in 10% formalin in neutral buffered saline for a minimum of 24 h, and most were decalcified with RDO Decal (Apex Engineering, Aurora, IL) prior to dehydration in a graded series of ethanol and embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with safranin O and Fast Green or hematoxylin and eosin, as described. (7)

Results

Engineered Cartilage Characterization

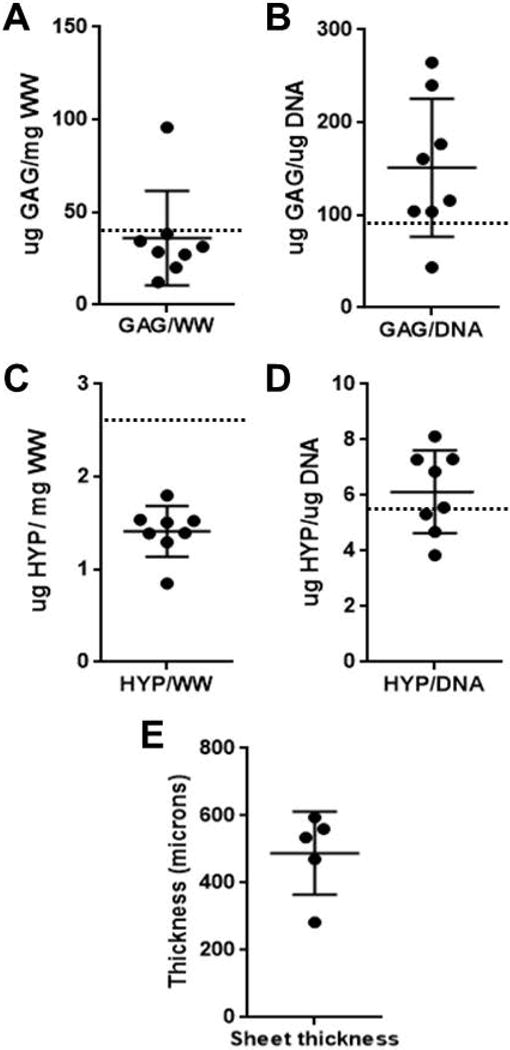

Sheets of cartilage were fabricated from auricular chondrocytes using a biochamber as previously described. A subset of cartilage sheets were assessed for thickness (490 +/− 120 microns), glycosaminoglycan (GAG) and collagen (hydroxyproline [HYP]) content, DNA content, and stiffness. The GAG content per wet weight (WW) and HYP content per wet weight were fairly consistent between samples, with the exception of one outlier (Figure 3). When compared to previous results on rabbit auricular chondrocytes (9), the current set of sheets contained approximately 60% more GAG per WW and approximately 50% less HYP per WW (Figure 3 A and C). In general, the GAG content per DNA was more highly variable between samples than was HYP per DNA (Figure 3B and D).

Figure 3. Glycosaminoglycan and collagen content of engineered cartilage sheets.

(A) shows the mean glycosaminoglycan (GAG) per wet weight (WW); (B) shows GAG per DNA; (C) shows hydroxyroline (HYP) per WW and (D) shows HYP per DNA. Sheet thickness is shown in (E). N = 8 for all samples. Dotted lines indicate values previously obtained in this laboratory for similarly prepared cartilage sheets. (9)

Surgical Summary

A series of implantations were conducted to evaluate different methodologies to produce viable replacement neotracheas for segmental tracheal replacement. The surgical and methodological issues that were tested included: 1) Structural integrity and viability of split thickness grafts performed using a two-step procedure and for 2) a one-step lining procedure; 3) The utility of promoting vascular ingrowth by punching holes into the cartilage sheath; 4) Examination of the structural integrity and epithelium status after segmental reconstruction;. A summary of those implantations are listed in Table 1. To date, 28 rabbits have been implanted. To assess the ability to fabricate neotracheas with a viable epithelial lining, 15 rabbits were lined using a two-step split-thickness skin graft lining approach where a skin lining is applied 6–8 weeks post implantation when the implant has become fully vascularized. A shorter, one-step method was tested in 3 rabbits were the implant is lined with skin at the same time as the initial implantation. Histological examination demonstrated that the epithelium of the rabbits using the one-step method was just as effective as the two-step method. The use of a one-step method has implications for clinical translation where the formation of a neotrachea could be accomplished in a single operation, and the total time for the implant to mature is significantly reduced. As a result, all but one of the rabbits used for tracheal reconstruction (11) had neotracheas fabricated using the one-step method.

Table 1.

Rabbit Surgery Summary

| Rabbit Number | One-Step | Two-step | SR | D Post-SR | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M9106 | √ | 4 | |||

| M9107 | √ | 4 | |||

| M9641 | √ | 4 | |||

| M9642 | √ | 4 | |||

| M9758 | √ | 4 | |||

| M9759 | √ | ||||

| N716 | √ | ||||

| N717 | √ | 4 | |||

| N718 | √ | 4 | |||

| N719 | √ | 4 | |||

| N835 | √ | 4 | |||

| N836 | √ | 4 | |||

| N5752 | √ | 1 | |||

| N2056 | √ | 1 | |||

| M7949 | √ | ||||

| N837 | √ | ||||

| N2055 | √ | 1 | |||

| N5753 | √ | √ | 8 | ||

| N6004 | √ | √ | 21 | ||

| N6005 | √ | √ | 1 | 2,3 | |

| N6006 | √ | √ | 11 | 2 | |

| N6007 | √ | √ | 8 | 2 | |

| 9766 | √ | √ | 7 | ||

| 9765 | √ | √ | 7 | ||

| 9767 | √ | √ | 21 | ||

| 9768 | √ | √ | 21 | ||

| 8476 | √ | √ | 7 | ||

| 8477 | √ | √ | 8 |

1-Weak/compromised neotrachea; 2-Cartilage sheets punched with holes; 3-T-tube displaced;4-cartilage displaced to one side; NT = Neotrachea; SR = Segmental Reconstruction; D = Days.

A total of 10 rabbits underwent segmental reconstruction, all with the use of T-tubes to stabilize the lumen. The reconstruction group also included 3 rabbits where the platysmal flap was wrapped outside of the cartilage sheet and whose cartilage sheets were punched with 3 mm or 4 mm holes to promote vascular ingrowth. This sub-study tested whether it was necessary to use the platysma muscle placed on the inside of the cartilage sheet as a source of vascularization for the epithelial layer (Table 1, Note 4) or whether vascular ingrowth through the holes was sufficient to support the overlying epithelium. Of the remaining 7 that had undergone tracheal reconstruction, the implants were left in place for 7–21 days before the animals were sacrificed for histologic examination. Prior to sacrifice, several of the tracheas were examined by a laryngoscope to evaluate the repair in situ. In each case, the engineered tracheas had a normal lumen and no adverse fibrosis was observed when examined by a laryngoscope (data not shown). Of the 10 tracheas used for tracheal reconstruction, 7 had a viable layer of epithelium and while 3 did not. Two of the samples without a viable epithelium were from the cartilage hole-punch group, where only one of three had a viable epithelium. Therefore, of the analyzable set of 7 tracheas not prepared with punched cartilage sheets, 6 of 7 (85.7%) had a viable epithelium.

It is noted that three of the tracheas scheduled for tracheal resection were, at the time of surgery, deemed insufficiently strong to maintain a patent airway (Table 1, Note 1). In addition, several of the neotracheas prepared using the 2-step lining procedure had insufficient neotracheal strength due to improper scruffing of the animals that lead to the cartilage sheet being displaced (Table 1, Note 4; Suppl. Fig. 1). A total of 27 neotracheas were palpated to assess whether there was sufficient structural integrity to undergo tracheal reconstruction. Overall, the success rate of fabricating neotracheas with structural integrity deemed appropriate for segmental repair was 55.6% (15 of 27). If the rabbits whose cartilage sheets had been compromised by inappropriate handling are discounted, the success rate was 88.2% (15 of 17).

Gross and Histologic Evaluation

Gross inspection of the neotracheas showed a patent lumen, with a thick, dense ring of tissue that was flexible and resilient when placed under compression (Figure 4A–C). Upon histological examination, 18 of 24 (75%) neotracheas – excluding 3 with the platysma muscle on the inside - exhibited a multi-layered tissue that included an inner epithelial layer, an intervening source of vasculature (platysma muscle) and an outer structural support layer composed of cartilage (Figure 4D). In some instances the cartilage layer became disrupted due, as was described above, to rough handling of the animals. It was also noted that in every neotrachea examined, as least some areas appeared to have undergone endochondral ossification (Figure 4E), with the presence of bone, and bone marrow, proximal to the implanted cartilage. The split thickness skin grafts showed the presence of healthy epithelial cells, including sweat glands (Figure 4F) and, when the grafts were too thick, the presence of growing hair follicles and sebaceous glands (not shown). The split thickness skin grafts did not always cover the entire circumference of the lumen and, in some areas, was quite sparse.

Figure 4. Gross examination and histology of neotracheas post-implantation.

Neotracheas showed a patent lumen (A) that can be fully compressed (B) and return to its original shape (C). Histological examination often showed that the cartilage sheet encompassed most of the lumen (D). Higher magnification revealed that some of the cartilage has undergone endochondral ossification where bone and marrow elements were visible (E). Split thickness skin grafts retained a viable epithelium (Ep) as well as sweat glands (SG). L = lumen; Cart = cartilage; BM = bone marrow.

While the use of platysma muscle was effective in supplying sufficient vasularization to support survival of the skin epithelium, it was hypothesized that if there were holes in the cartilage, a sufficient amount of fibrous tissue containing vasculature would form proximal to the silicone tube so that an epithelial layer would survive using the two-step implantation method. However, examination of these samples with holes in the cartilage showed inconsistent levels of surviving epithelium (1 of 3 showed viable epithelium) even though the holes did, indeed, provide a path for vascular ingrowth (Figure 5D and E).

Figure 5. Segmental Reconstruction.

An example of a skin-lined neotrachea reconstruction is shown in A–C. The neotrachea abuts the native trachea containing native cartilage (NC) and native columnar epithelium (NCE); sutures (ST) are evident on the neotrachea side. Asterisks mark skin epithelium in A and B. A neotrachea with the platysma muscle on the outside of the cartilage layer is shown in D and E, where only fibrous tissue (FT) is located on the luminal (L) surface. F shows a high magnification of the native tissue proximal to the neotrachea. B = bone; SE = skin epithelium; EC = engineered cartilage; PL = platysma layer; arrows in D and E point to vascular ingrowth.

Segmental Reconstruction

Eleven rabbits underwent segmental reconstruction, with the amount of time ranging from 1 to 21 days. The rabbit having a segmental reconstruction for only 1 day expired because of a displaced t-tube (Table 1). An example of a reconstructed skin-lined neotrachea is shown in Figure 5 (A–C and F) from rabbit 9766, which was harvested 7 days post-implantation. The engineered cartilage showed what appears to be a viable skin epithelium (Fig. 4 B and C) adjacent to native columnar epithelium (Fig. F). A neotrachea with the platysma muscle on the outside of the cartilage instead of the inside is shown in Figure 5 (D and E), where the luminal side shows only fibrous tissue. In all reconstructions the engineered cartilage was less intensely stained for proteoglycans than was native cartilage or the engineered cartilage tissue that had not undergone segmental reconstruction (Figure 4E). None of the rabbits showed any signs of infection and there was no evidence of failure at the interface between the native and engineered tissues (Figure 5 A–C).

Discussion

The results shown here demonstrate the feasibility of using a combined surgical and tissue engineering approach to fabricate a functional neotracheal tissue composed of multiple distinct layers of cartilage, muscle and epithelium. It was demonstrated that a tri-layered trachea replacement tissue, a “neotrachea”, could be fabricated from tissue engineered cartilage sheets combined with a vascularized support tissue, in this case, platysma muscle, that has been lined with a split-thickness skin graft. These studies set the stage for future studies that focus on the development of methods to line the neotrachea with autologous mucosal cells. The key elements in this study were that the implanted cartilage retains its structural integrity, the epithelial lining becomes engrafted and remains viable, and the surgical methods have been refined to optimize outcomes.

Multiple laboratories have approached the issue of engineering neotracheas using different techniques, including the use of biomaterials, decellularized cadaveric tracheas, and a combination of biomaterials or decellularized tissues with progenitor cells (3). The use of decellularized cadaveric trachea was first attempted in people as a compassionate use where a patient with end-stage bronchomalacia was implanted with a decellularized cadaveric trachea that was seeded with autologous cells. (4) While this particular case worked out well for the patient, the process was not standardized and the outcomes in other patients having similar implants entailed multiple surgeries and even some fatalities. (5, 11) These results emphasize the need to develop a standardized method to produce a functional trachea replacement that is, ideally, free of severe complications.

The completely synthetic approach has not, as yet, proved to be successful as the implants suffer from multiple detriments, including bio-incompatibility, some inflammatory reactions (12, 13), inability to integrate effectively into native tissue (14), and the inability to grow with the patient. Examples of synthetic materials that have been investigated for tracheal engineering include polyglycolic acid (PGA), and polyglycolic acid/poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PGLA), poly (ethylene oxide)-terephathalate/poly(butylene terephathalate), polyethylene oxide/polypropylene oxide copolymer (Pluronic F-127), polyester urethane, gelatin sponge and polytetrafluoroethylene (reviewed in (3)). These implant materials have shown some limited success, but have always fallen short of providing a fully functional tracheal replacement. PGA(12) and PGLA (13) elicited an inflammatory reaction, while polyester urethane was never tested in vivo (15) and polytetrafluoroethylene was only tested in an ectopic site in rat model. (16) Gelatin sponge, combined with BMP-2, was only tested in hemi-segments trachea in a dog model, but did show cartilage and bone formation – the status of the epithelium was not reported. (17) The Pluoronic F-127 study showed some promise for patching tracheas in a pig model, but no follow-up study demonstrated its effectiveness to repair a segmental defect. (18) One study avoided the issue of inflammation caused by scaffold material, in this case polyglycolic/polylactic acid (PGA/PLA) fibers, by pre-incubating the PGA/PLA fibers with chondrocytes two weeks prior to implantation. (19) This study also used a post-implantation maturation process similar to the one described here, except that the stenohyoid muscle was used to wrap the construct instead of the platysma muscle used in this case. Interestingly, this publication by Luo et al. (19) showed that significant mucosal epithelium ingrowth can occur if the lumen stabilized with a silicone tube for 8 weeks.

This laboratory, and others, have taken a scaffold-free, autologous cell approach to fabricating a neotrachea as another means to avoid problems with inflammation. Tani et al. (21) showed that rabbit chondrocytes could be used to form sheets of cartilage that, after being wrapped around a silicone tube for 6 weeks, has 72% of the mechanical strength of native cartilage. Interestingly, when another group tested a similar method to fabricate cartilage sheets and examined sheets implanted in rabbits for 8 weeks, they also found that the implants had 72% the mechanical strength of native tissue. (20) However, the construct was never tested in a tracheal reconstruction model, nor was there any attempt to fabricate an epithelium. Another study from this laboratory (6) used a scaffold-free method to produce cartilage patches in a rabbit model, which formed the basis for expanding the methodology to repair larger segmental defects.

Interestingly, while the source of chondrocytes used in two of these studies(19–21) was identical to ours - auricular chondrocytes from New Zealand rabbits - there was no mention of endochondral ossification, which was observed here in every instance (Figure 4D and E). The observed formation of endochondral bone is interesting in that auricular cartilage is known to express high levels of type X collagen (22), a common but not a definitive marker of hypertrophic chondrocytes, but native ear cartilage never ossifies. One possibility is that the anatomic location of the ear impedes hypertrophy. However, when native pieces of auricular cartilage were implanted proximal to neotracheas implanted in the neck region, no endochondrial ossification was observed in native ear cartilage even after 12 weeks in vivo (unpublished observations), thus indicating that there is an inherent difference between native auricular chondrocytes and auricular chondrocytes that have been culture expanded.

The identification of endochondral bone formation raises the question as to the clinical applicability of a neotrachea construct that becomes calcified and, in fact, ossified. There is some indication that rigidity might not be a major concern because calcification of tracheal tissue is actually quite common and increases with age in both men and women. (23) However, flexibility may be important for mucous clearance during coughing, head movement and during swallowing. To account for these potentially important mechanical properties, alternative methods for fabrication include the use of a different source of chondrocytes, such as nasal or articular, and the use of cartilage implant segments interspersed with fibrous layers that mimic the ring structure of native trachea.

Weaknesses

There are several weaknesses to this study. For one, the use of skin epithelium is less than ideal as it provides no mucus production or cilia to allow mucus clearance and, as a result, is a likely source of obstruction. Also, while the epithelium coverage was complete in some specimens, most had at least some regions devoid of any epithelium. While some reparative ingrowth from the edges is expected (6, 24–26), the amount of ingrowth is often limited to only 2–3 millimeters. In addition, several of the implanted tracheas were lined with skin grafts that were too thick and contained hair follicles. Another weakness is that this study was restricted to the segmental reconstruction with neotracheas lined with T-tubes. While all of the neotracheas showed good cellular integration and were able to retain their shape when palpated at harvest, the ability of the neotracheas to function independently was not fully tested. One key issue that has yet to be addressed is delamination of the skin layer, which was observed to occur quite easily when the neotracheas were harvested. This delamination issue will need to be addressed in any future studies. Finally, mechanical testing was not conducted because the cross sections of the samples were complex, containing variable amounts of cartilage, muscle, connective tissue and, most importantly, bone, which precluded obtaining meaningful material properties.

Conclusions

The method outlined here shows how engineered cartilage can be used to provide structural support to an engineered neotrachea lined with skin epithelium and where both layers are supported by a platysma muscle flap. The surgical methods outline both a means to fabricate the neotrachea proximal to the trachea and a surgical method for conducting the segmental reconstruction. These results provide the foundation for developing a functional neotrachea construct with the vascular support necessary for maintenance of cartilage integrity and for the support of a viable epithelial layer. The challenge now is to produce neotracheas with an integrated layer of mucosal epithelium.

Supplementary Material

Safranin O/Fast Green-stained histological section showing cartilage (C) in folds at one edge the lumen (L) instead of circumferentially. HF = Hair follicles.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shenna Washington at the Benaroya Research Institute for histology processing and staining, Alex Yazdi for biochemical assays, and Kathleen Wagner and Jordan Peitz for the illustrations.

References

- 1.Fuchs JR, Terada S, Ochoa ER, Vacanti JP, Fauza DO. Fetal tissue engineering: in utero tracheal augmentation in an ovine model. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1000. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.33829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogan SL, Teoh GZ, Birchall MA. Tissue Engineered Airways: A Prospects Article. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2016;117:1497. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ott LM, Weatherly RA, Detamore MS. Overview of tracheal tissue engineering: clinical need drives the laboratory approach. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2011;39:2091. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0318-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macchiarini P, Jungebluth P, Go T, Asnaghi MA, Rees LE, Cogan TA, Dodson A, Martorell J, Bellini S, Parnigotto PP, Dickinson SC, Hollander AP, Mantero S, Conconi MT, Birchall MA. Clinical transplantation of a tissue-engineered airway. Lancet. 2008;372:2023. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61598-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogel G. Trachea transplants test the limits. Science. 2013;340:266. doi: 10.1126/science.340.6130.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilpin DA, Weidenbecher MS, Dennis JE. Scaffold-free tissue-engineered cartilage implants for laryngotracheal reconstruction. The Laryngoscope. 2010;120:612. doi: 10.1002/lary.20750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weidenbecher M, Tucker HM, Awadallah A, Dennis JE. Fabrication of a neotrachea using engineered cartilage. The Laryngoscope. 2008;118:593. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318161f9f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weidenbecher M, Tucker HM, Gilpin DA, Dennis JE. Tissue-engineered trachea for airway reconstruction. The Laryngoscope. 2009;119:2118. doi: 10.1002/lary.20700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitney GA, Mera H, Weidenbecher M, Awadallah A, Mansour JM, Dennis JE. Methods for producing scaffold-free engineered cartilage sheets from auricular and articular chondrocyte cell sources and attachment to porous tantalum. BioResearch open access. 2012;1:157. doi: 10.1089/biores.2012.0231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrino DA, Arias JL, Caplan AI. A spectrophotometric modification of a sensitive densitometric Safranin O assay for glycosaminoglycans. Biochem Int. 1991;24:485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler C, Birchall M, Giangreco A. Interventional and intrinsic airway homeostasis and repair. Physiology (Bethesda) 2012;27:140. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00001.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kojima K, Ignotz RA, Kushibiki T, Tinsley KW, Tabata Y, Vacanti CA. Tissue-engineered trachea from sheep marrow stromal cells with transforming growth factor beta2 released from biodegradable microspheres in a nude rat recipient. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:147. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo X, Zhou G, Liu W, Zhang WJ, Cen L, Cui L, Cao Y. In vitro precultivation alleviates post-implantation inflammation and enhances development of tissue-engineered tubular cartilage. Biomed Mater. 2009;4:1. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/4/2/025006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toomes H, Mickisch G, Vogt-Moykopf I. Experiences with prosthetic reconstruction of the trachea and bifurcation. Thorax. 1985;40:32. doi: 10.1136/thx.40.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang L, Korom S, Welti M, Hoerstrup SP, Zund G, Jung FJ, Neuenschwander P, Weder W. Tissue engineered cartilage generated from human trachea using DegraPol scaffold. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2003;24:201. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matloub HS, Yu P. Engineering a composite neotrachea in a rat model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:123. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000185607.96476.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Igai H, Chang SS, Gotoh M, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto M, Tabata Y, Yokomise H. Tracheal cartilage regeneration and new bone formation by slow release of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-2. ASAIO J. 2008;54:104. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e31815fd3d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamil SH, Eavey RD, Vacanti MP, Vacanti CA, Hartnick CJ. Tissue-engineered cartilage as a graft source for laryngotracheal reconstruction: a pig model. Archives of otolaryngology–head & neck surgery. 2004;130:1048. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.9.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo X, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Tao R, Liu Y, He A, Yin Z, Li D, Zhang W, Liu W, Cao Y, Zhou G. Long-term functional reconstruction of segmental tracheal defect by pedicled tissue-engineered trachea in rabbits. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3336. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu W, Cheng X, Zhao Y, Chen F, Feng X, Mao T. Tissue engineering of trachea-like cartilage grafts by using chondrocyte macroaggregate: experimental study in rabbits. Artif Organs. 2007;31:826. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2007.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tani G, Usui N, Kamiyama M, Oue T, Fukuzawa M. In vitro construction of scaffold-free cylindrical cartilage using cell sheet-based tissue engineering. Pediatric surgery international. 2010;26:179. doi: 10.1007/s00383-009-2543-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naumann A, Dennis JE, Awadallah A, Carrino DA, Mansour JM, Kastenbauer E, Caplan AI. Immunochemical and mechanical characterization of cartilage subtypes in rabbit. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry: official journal of the Histochemistry Society. 2002;50:1049. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lloyd DC, Taylor PM. Calcification of the intrathoracic trachea demonstrated by computed tomography. Br J Radiol. 1990;63:31. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-63-745-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erjefalt JS, Erjefalt I, Sundler F, Persson CG. In vivo restitution of airway epithelium. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;281:305. doi: 10.1007/BF00583399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zahm JM, Kaplan H, Herard AL, Doriot F, Pierrot D, Somelette P, Puchelle E. Cell migration and proliferation during the in vitro wound repair of the respiratory epithelium. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1997;37:33. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1997)37:1<33::AID-CM4>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chopra DP, Kern RC, Mathieu PA, Jacobs JR. Successful in vitro growth of human respiratory epithelium on a tracheal prosthesis. The Laryngoscope. 1992;102:528. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199205000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Safranin O/Fast Green-stained histological section showing cartilage (C) in folds at one edge the lumen (L) instead of circumferentially. HF = Hair follicles.