Abstract

Objective

To test the hypothesis that higher level of purpose in life is associated with lower subsequent odds of hospitalization.

Design

Longitudinal cohort study.

Setting

Participants' residences in the Chicago metropolitan area.

Participants

A total of 805 older persons who completed uniform annual clinical evaluations.

Measurements

Participants annually completed a standard self-report measure of purpose in life, a component of well-being. Hospitalization data were obtained from Part A Medicare claims records. Based on previous research, ICD-9 codes were used to identify ambulatory care-sensitive conditions (ACSCs) for which hospitalization is potentially preventable. The relation of purpose (baseline and follow-up) to hospitalization was assessed in proportional odds mixed models.

Results

During a mean of 4.5 years of observation, there was a total of 2,043 hospitalizations (442 with a primary ACSC diagnosis, 1,322 with a secondary ACSC diagnosis, 279 with no ACSCs). In initial analyses, higher purpose at baseline and follow-up were each associated with lower odds of more hospitalizations involving ACSCs but not hospitalizations for non-ACSCs. Results were comparable when those with low cognitive function at baseline were excluded. Adjustment for chronic medical conditions and socioeconomic status reduced but did not eliminate the association of purpose with hospitalizations involving ACSCs.

Conclusions

In old age, higher level of purpose in life is associated with lower odds of subsequent hospitalizations for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions.

Keywords: purpose in life, well-being, hospitalization, Medicare

Introduction

With the aging of the United States population in the coming decades, expenditure on health care is expected to markedly increase. Hospitalization is a major driver of health care expenditure, with older adults accounting for a large proportion of aggregate costs. In 2008, for example, Americans age 65 and older accounted for 40% of all hospital costs despite comprising less than 13% of the United States population (1), and these costs are likely to increase as the population continues to age. In addition, after hospitalization older persons are at increased risk of disability (2-4), cognitive impairment (5), and cognitive decline (6). Therefore, even a small decrease in the elderly hospitalization rate, which is approximately 350 discharges per 1000 Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older per year (7), could have substantial financial and public health benefits.

Research on psychological factors affecting health care utilization has primarily focused on negative traits such as depression which may increase the need for services, decrease the ability to appropriately access services, or both, but recent research has suggested that positive traits also play a role in health maintenance (8,9). In the present study, we focus on purpose in life, a component of well-being denoting a sense that one's life has direction and meaning (10).

Several factors suggest that purpose in life may be related to hospitalization in old age. First, in prospective studies, higher level of purpose predicts better health outcomes including increased longevity (11,12) and decreased risk of common chronic conditions such as depression (13,14), vascular disease (15,16), and dementia (17). Second, among individuals who already have chronic conditions, higher purpose is associated with more effective management (18) and better outcomes (19). Third, longitudinal research suggests that purpose tends to decline in late life (20). We are aware of one prior study of purpose and hospitalization. It found that higher level of purpose was associated with decreased hospitalization (21), but it did not account for person-specific change in purpose and hospitalization was assessed by retrospective self-report, which may be biased in older persons (22-25), particularly those with lower levels of cognitive function (25,26).

In the present analyses, we use data from a longitudinal cohort study to test the hypothesis that higher level of purpose is associated with lower odds of subsequent hospitalizations. To obviate recall bias, data on hospitalization were obtained from Medicare claims records. Because prior research suggests that purpose is not only related to risk of developing selected medical conditions but also to how effectively medical conditions are managed, we also hypothesized that the association of purpose with hospitalization would persist after adjustment for chronic conditions related to purpose and that the association would be strongest for hospitalizations deemed potentially preventable with proactive outpatient care.

Methods

Participants

Analyses are based on participants in the Rush Memory and Aging Project, a longitudinal cohort study begun in 1997 (27, 28). Recruitment from continuous care retirement communities, subsidized senior housing, social service agencies, and churches in the Chicago metropolitan region is ongoing. After a presentation at each site, interested persons meet with study staff for a more detailed discussion of the project. Eligibility criteria are age >50 at enrollment, absence of a prior dementia diagnosis, and agreement to annual clinical evaluations and brain autopsy at death. For the present analyses, we used data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project collected from 3-22-1999 to 12-31-2010, the period for which Medicare claims data were available. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The project was approved by the institutional review board of Rush University Medical Center.

Assessment of Purpose in Life

Purpose in life was assessed annually with 10 items derived from Ryff's Scales of Psychological Well-Being (13). Participants rated agreement with each item on a 5-point scale (e.g., “I have sense of direction and purpose in life”; “I feel good when I think of what I've done in the past and what I hope to do in the future”). The item scores were averaged to yield a total score ranging from 1 to 5 with higher values indicating higher levels of the trait. In previous research, this scale has shown adequate internal consistency (29) and predicted diverse health outcomes including disability (30), cognitive decline (20), dementia (17), and death (12).

Assessment of Hospitalization

Data on hospital use from 03-22-1999 through 12-31-2010 were obtained from Part A Medicare claims records. We used ICD-9 codes to identify hospitalizations involving ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs), which are potentially preventable with proactive outpatient care (31,32). Based on previously designed classification schemes to identify conditions relevant to the older adult population, the following conditions were classified as ACSCs: angina, asthma, bacterial pneumonia, cellulitis, congestive heart failure exacerbation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation, dehydration, diabetes, duodenal ulcer, ear/nose/ throat infection, gastric ulcer, gastroenteritis, hypertension, hypoglycemia, hypokalemia, influenza, malnutrition, peptic ulcer, seizure disorder, and urinary tract infection (33,34). Examples of non-ACSCs included dysrhythmia, transient ischemic attack, acute myocardial infarction, septicemia, and hip fracture.

Assessment of Covariates

Cognitive function was assessed at baseline with a battery of 17 performance tests in an approximately one hour session. The battery included 7 measures of episodic memory, 3 measures of semantic memory, 3 measures of working memory, 2 measures of perceptual speed and 2 measures of visuospatial ability, as previously described (35-37). Raw test scores were converted to z scores using the baseline mean and standard deviation. The z scores on the individual tests were averaged to yield a composite measure of global cognition. In analyses, we defined low cognitive function as a global cognitive score at or below the 10th percentile at baseline. Further information on the individual tests and composite measure of global cognition has been previously published (35-37).

Each annual clinical evaluation included a structured medical history. Because purpose has been associated with vascular disease (15,16,19), we created summary measures of vascular risk factors (number of 3 risk factors present: hypertension, diabetes, smoking) and vascular conditions (number of 4 conditions present: myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, claudication). Purpose has also been associated with depressive symptoms (13,14) which were assessed with a 10-item version (38) of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (39). The score was the number of 10 symptoms present much of the time in the past week. In analyses, we used the number of vascular risk factors, vascular conditions, and depressive symptoms averaged across annual evaluations to capture the burden of these common chronic health problems during the observation period. Because of the well-established socioeconomic disparities in health (40), we use educational attainment as an indicator of current socioeconomic status and paternal education, maternal education, and number of children in the family were converted to standard scores and averaged to characterize early life socioeconomic status, as previously described (41).

Statistical Analysis

The outcome variable, number of hospitalizations per follow-up year, is discrete and zero-inflated. To provide parsimonious modeling, the hypothesized relation of purpose to more hospitalization was assessed in a series of mixed effect proportional odds models. Mixed effects models have a hierarchical structure that can account for correlations of repeated measures across time within persons. These models allowed us to accommodate time-varying fluctuations in purpose as well as unequally spaced intervals between assessments. We first analyzed all hospitalizations and then subtypes of hospitalizations. All models included terms for age (at baseline, centered at 81 years), sex, and education (centered at 15 years). To make use of all data on purpose, terms were included for purpose at baseline and, to capture temporal fluctuations in purpose, the time varying deviations of purpose on follow-up from purpose at baseline. In subsequent analyses, we excluded those with low cognitive function at baseline and added indicators of health and socioeconomic status. The proportionality assumption was assessed with the score test for proportional odds and the trend odds model (42) and found to be adequately met. Estimates obtained represent the log odds of hospitalizations per year. We illustrate the effect of a high level of purpose in life compared to a typical level of purpose by calculating the log odds ratio of a person with 90th percentile of baseline purpose (score = 4.2) compared to a person with 50th percentile of baseline purpose (score = 3.7). Similarly, we illustrate the effect of a low level of purpose in life compared to a typical level of purpose by calculating the log odds ratio of a person with 10th percentile of baseline purpose (score = 3) compared to a person with 50th percentile of baseline purpose. Analyses were programmed in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A threshold of p<0.05 was set for statistical significance.

Results

The 805 participants had a mean age at baseline of 81.1 years (SD=6.8, range: 64-100), they had a mean of 14.7 years of education (SD=3.1); 600 (74.5%) were women; and 743 (92.3%) were White and not Latino. During up to 9 years of observation (mean=4.5 years, SD=2.3, range: 1-9), there were 2,043 hospitalizations, with 223 persons never hospitalized (27.7%) and 582 hospitalized one or more times over the entire follow-up period (152[1], 125[2], 81 [3], 71[4], 53[5], 100[ ≥ 6]), and an overall mean of 0.41 hospitalizations per year (SD=0.94).

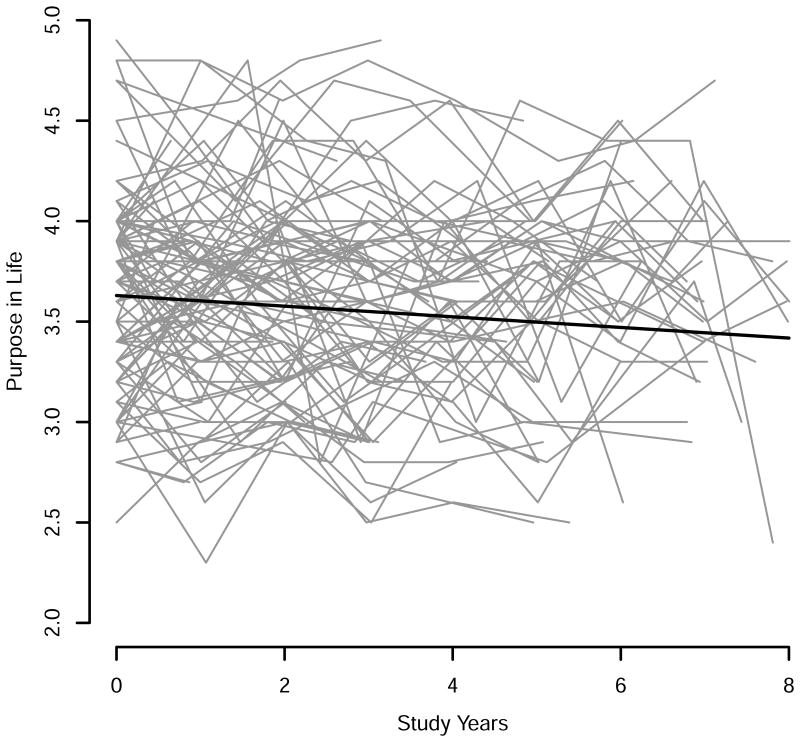

At baseline, level of purpose ranged from a low of 2 to a high of 5 (mean = 3.63, SD = 0.46). As shown in Figure 1, there was much variability in how purpose changed over time (thin gray lines) but an overall tendency for purpose to decline (thick black line), estimated in an unadjusted mixed-effects model to be a mean loss of 0.026-unit per year (SE=0.003, df =3526, t=9.2, p<0.001). To test for the hypothesized association of purpose in life with hospitalization, we constructed a series of mixed effect proportional odds models with odds of more hospitalizations in each follow-up year as the outcome. All of these analyses included terms for the potentially confounding effects of age (at baseline), sex, and years of formal education. Terms were also included for baseline level of purpose and the time-varying deviation of purpose from baseline purpose.

Figure 1. Crude paths of change in purpose in life in a random sample of 100 participants (gray lines) and the mean path estimated from an unadjusted mixed-effects model (black line).

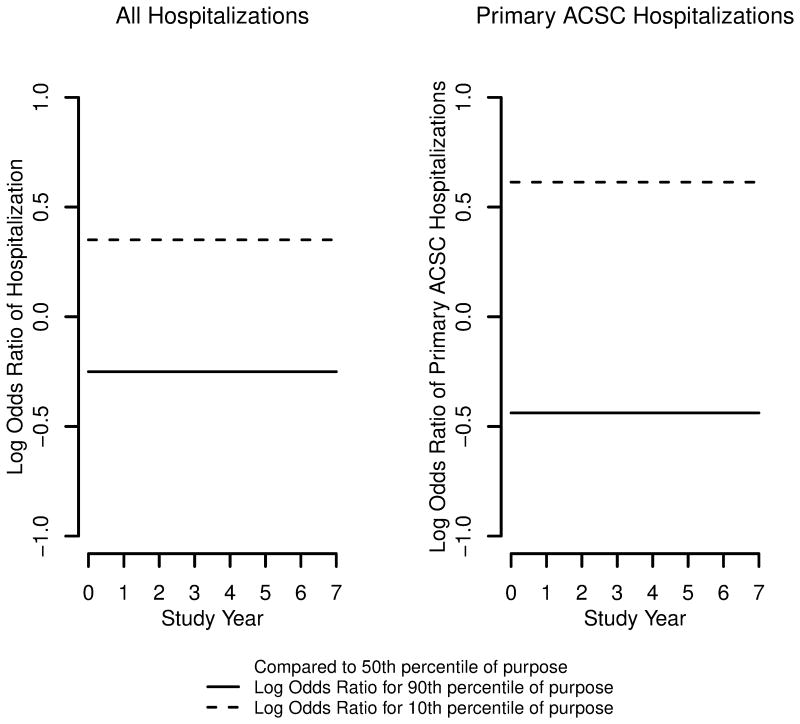

In the initial analysis (Table 1, all hospitalizations), the odds of hospitalization were relatively stable across the observation period as shown by the term for time. There were no sex differences, but older age and fewer years of education were related to higher odds of hospitalization. With these demographic associations accounted for, higher level of purpose at baseline and higher level of purpose during follow-up were each associated with lower odds of hospitalization, with protective effects of purpose in life (in log odds) about 10 times greater than the effects of education. For example, an increase of one unit in purpose at baseline was associated with a 39.4% decrease in the odds of having more hospitalizations in general (all hospitalizations) and an increase of one unit in the time-varying deviation of follow-up purpose from baseline purpose was associated with a 38.6 decrease in the odds of having more hospitalizations. Figure 2 shows the log odds ratio of hospitalization for a person with a high (solid line) or low (dashed line) level of purpose in life compared to a person with a median level of purpose in life. The log odds of hospitalization for a person with a high level of purpose in life was -0.25 (an odds ratio of 0.778); this represents a reduction of 22.2% in odds compared to a person with a median level of purpose in life.

Table1. Relation of purpose to hospitalization*.

| All Hospitalizations | ACSC Primary Diagnoses | ACSC Secondary Diagnoses | No ACSC Diagnoses | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Model term |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Log Odds Ratio |

SE | df | t- value |

P | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Log Odds Ratio |

SE | df | t- value |

p | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Log Odds Ratio |

SE | df | t- value |

p | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Log Odds Ratio |

SE | df | t- value |

P |

| Time | 1.017 (0.981,1.053) | 0.017 | 0.02 | 805 | 0.92 | 0.36 | 1.025 (0.933,1.126) | 0.025 | 0.05 | 804 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 1.034 (0.994,1.074) | 0.033 | 0.02 | 804 | 1.68 | 0.09 | 0.979 (0.8741.096), | -0.021 | 0.06 | 804 | -0.37 | 0.71 |

| Baseline age | 1.039 (1.021,1.057) | 0.038 | 0.01 | 2714 | 4.29 | <0.001 | 1.048 (1.021,1.076) | 0.047 | 0.01 | 2719 | 3.56 | <0.001 | 1.033 (1.016,1.051) | 0.033 | 0.01 | 2717 | 3.8 | <0.001 | 0.999 (0.973,1.025) | -0.001 | 0.01 | 2720 | -0.11 | 0.91 |

| Sex | 1.062 (0.826,1.365) | 0.06 | 0.13 | 2714 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 1.227 (0.845,1.782) | 0.205 | 0.19 | 2719 | 1.08 | 0.28 | 1.017 (0.796,1.298) | 0.016 | 0.13 | 2717 | 0.13 | 0.90 | 1.233 (0.846,1.796) | 0.21 | 0.19 | 2720 | 1.00 | 0.28 |

| Education | 0.957 (0.92, 0.994) | -0.044 | 0.02 | 2714 | -2.26 | 0.02 | 0.951 (0.898,1.008) | -0.05 | 0.03 | 2719 | -1.68 | 0.09 | 0.955 (0.92, 0.992) | -0.046 | 0.02 | 2717 | -2.39 | 0.02 | 0.949 (0.895,1.006) | -0.052 | 0.03 | 2720 | -1.75 | 0.08 |

| Baseline purpose | 0.606 (0.469,0.782) | -0.501 | 0.13 | 2714 | -3.84 | <0.001 | 0.416 (0.284,0.611) | -0.877 | 0.2 | 2719 | -4.48 | <0.001 | 0.614 (0.479,0.788) | -0.487 | 0.13 | 2717 | -3.84 | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.684, 1.52) | 0.02 | 0.2 | 2720 | 0.1 | 0.92 |

| Time varying purpose | 0.615 (0.492,0.768) | -0.487 | 0.11 | 2714 | -4.29 | <0.001 | 0.521 (0.363,0.748) | -0.651 | 0.18 | 2719 | -3.53 | <0.001 | 0.601 (0.473,0.763) | -0.509 | 0.12 | 2717 | -4.18 | <0.001 | 1.684 (1.102,2.573) | 0.521 | 0.22 | 2720 | 2.41 | 0.02 |

From 4 proportional odds models. ACSC, ambulatory care-sensitive conditions; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error; df, degrees of freedom.

Figure 2.

Log odds ratio of hospitalizations per year for those with high (90h percentile, solid line) or low (10th percentile, dashed line) purpose in life compared to those with median purpose (50th percentile), from proportional odds models adjusted for age, sex, and education.

Of the 2,043 hospitalizations, 442 had a primary ACSC diagnosis, 1,322 had a secondary ACSC diagnosis, and 279 had no ACSC diagnoses. The 442 primary ACSC diagnoses were bacterial pneumonia (n=97), congestive heart failure exacerbation (n=87), urinary tract (n=62), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation (n=39), cellulitis (n=33), dehydration (n=25), asthma (n=21), hypertension (n=14), diabetes (n=13), gastroenteritis (n=12), duodenal ulcer (n=10), influenza (n=9), gastric ulcer (n=8), seizure disorder (n=5), angina (n=4), hypokalemia (n=2), and hypoglycemia (n=1).

We repeated the initial analysis separately for each of these hospitalization subtypes (Table 1). Higher levels of purpose at baseline and follow-up were associated with lower odds of ACSC hospitalizations, with a stronger association for primary ACSC diagnoses than secondary ACSC diagnoses. For example, a one unit increase in baseline purpose was associated with a 58.4% decrease in the odds of having more hospitalizations with primary ACSC diagnoses and a 38.6% decrease in the odds of having more hospitalizations with secondary ACSC diagnoses. A one unit increase in purpose on follow-up relative to baseline was associated with a 47.8% decrease in the odds of hospitalizations with primary ACSC diagnoses and a 39.9% decrease in the odds of hospitalizations with secondary ACSD diagnoses. Figure 2 shows that the log odds of hospitalization with a primary ACSC diagnosis for a person with a high level of purpose in life was -0.438 (an odds ratio of 0.645); this represents a reduction of 35.5% in odds compared to a person with a median level of purpose in life. By contrast, baseline purpose was unrelated to non-ACSC hospitalization and higher follow-up purpose was associated with higher odds of non-ACSC hospitalization.

To determine whether lower cognitive functioning might account for the association of purpose with hospitalizations, we repeated the initial analyses after excluding persons who had a low level of global cognitive function at baseline (at or below the 10th percentile). In these analyses, the associations of purpose at baseline and follow-up with odds of more of each type of hospitalization were comparable to the original analyses (data not shown).

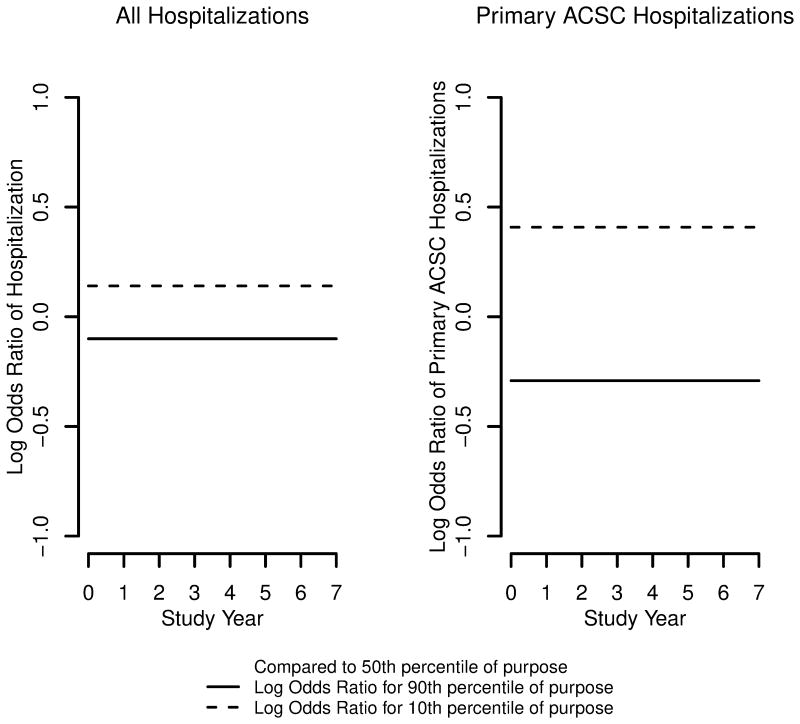

To assess whether depression, vascular disease, or socioeconomic status affected results, we repeated the initial analyses with 4 terms added: mean number of 3 vascular risk factors (mean=1.2, SD=0.8), 4 vascular conditions (mean=0.5, SD=0.7), and 10 depressive symptoms (mean=1.3, SD=1.4) averaged across the full observation period plus a term for early life socioeconomic status (mean=0.0, SD=0.7) (Table 2). In these analyses, higher purpose at baseline was associated with lower odds of hospitalization with a primary ACSC diagnosis, though the level of the association was reduced and purpose was no longer associated with other hospitalization outcomes (Table 2). Higher purpose on follow-up was associated with lower odds of an ACSC hospitalization but not of a non-ACSC hospitalization. Thus, the odds of having more hospitalizations with ACSC primary diagnoses were 44.2% lower for each one unit increase in baseline purpose and 40.2% lower for each one unit increase in purpose on follow-up relative to baseline. Figure 3 shows that the log odds of hospitalization with a primary ACSC diagnosis for a person with a high level of purpose in life was -0.291 (an odds ratio of 0.747); this represents a reduction of 25.3% in odds compared to a person with a median level of purpose in life.

Table 2. Relation of purpose to hospitalization with health-related and socioeconomic covariates*.

| All Hospitalizations | ACSC Primary Diagnoses | ACSC Secondary Diagnoses | No ACSC Diagnoses | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Model term |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Log Odds Ratio |

SE | df | t-value | p | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Log Odds Ratio |

SE | df | t- value |

p | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Log Odds Ratio |

SE | df | t- value |

P | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Log Odds Ratio |

SE | df | t- value |

p |

| Time | 1.047 (1.011,1.084) | 0.046 | 0.02 | 796 | 2.59 | 0.01 | 1.01 (0.918,1.112) | 0.01 | 0.05 | 795 | 0.21 | 0.84 | 1.036 (0.996,1.077) | 0.035 | 0.02 | 795 | 1.78 | 0.08 | 0.982 (0.919,1.048) | -0.019 | 0.03 | 795 | -0.56 | 0.58 |

| Baseline age | 1.035 (1.019,1.052) | 0.035 | 0.01 | 2691 | 4.24 | <0.001 | 1.049 (1.021,1.077) | 0.048 | 0.01 | 2695 | 3.51 | <0.001 | 1.036 (1.019,1.054) | 0.036 | 0.01 | 2693 | 4.11 | <0.001 | 0.991 (0.966,1.018) | -0.009 | 0.01 | 2696 | -0.66 | 0.51 |

| Sex | 1.061 (0.842,1.336) | 0.059 | 0.12 | 2691 | 0.5 | 0.62 | 1.096 (0.752,1.597) | 0.092 | 0.19 | 2695 | 0.48 | 0.63 | 0.962 (0.755,1.226) | -0.038 | 0.12 | 2693 | -0.31 | 0.76 | 1.357 (0.929,1.983) | 0.305 | 0.19 | 2696 | 1.58 | 0.11 |

| Education | 0.951 (0.915,0.988) | -0.051 | 0.02 | 2691 | -2.59 | 0.01 | 0.954 (0.895, 1.016) | -0.048 | 0.03 | 2695 | -1.47 | 0.14 | 0.954 (0.895,1.016) | -0.045 | 0.02 | 2693 | -2.18 | 0.02 | 0.928 (0.87, 0.99) | -0.075 | 0.03 | 2696 | -2.26 | 0.02 |

| Baseline purpose | 0.818 (0.632,1.06) | -0.201 | 0.13 | 2691 | -1.52 | 0.13 | 0.558 (0.366,0.852) | -0.583 | 0.22 | 2695 | -2.71 | 0.01 | 0.832 (0.635,1.091) | -0.184 | 0.14 | 2693 | -1.33 | 0.18 | 1.076 (0.694, 1.668) | 0.073 | 0.22 | 2696 | 0.33 | 0.74 |

| Time varying deviation in purpose | 0.786 (0.63, 0.982) | -0.24 | 0.11 | 2691 | -2.12 | 0.03 | 0.598 (0.411,0.869) | -0.514 | 0.19 | 2695 | -2.69 | 0.01 | 0.711 (0.557,0.907) | -0.341 | 0.12 | 2693 | -2.74 | 0.01 | 1.515 (0.986,2.329) | 0.416 | 0.22 | 2696 | 1.9 | 0.06 |

From 4 proportional odds models adjusted for vascular risk factors, vascular conditions, depressive symptoms, and early life socioeconomic status. ACSC, ambulatory care-sensitive conditions; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error; df, degrees of freedom.

Figure 3.

Log odds ratio of hospitalizations per year for those with high (90h percentile, solid line) or low (10th percentile, dashed line) purpose in life compared to those with median purpose (50th percentile), from proportional odds models adjusted for age, sex, and education, vascular risk factors, vascular conditions, depressive symptoms, and early life socioeconomic status.

Discussion

During a mean of nearly 5 years of observation of a group of approximately 800 older persons, nearly 600 were hospitalized a total of more than 2,000 times. Higher level of purpose in life at baseline and higher purpose during follow-up were each associated with lower subsequent odds of hospitalization after adjustment for chronic vascular conditions, depression, and socioeconomic status, but the association was mainly restricted to hospitalizations for ACSCs. The results suggest that those with a high sense of purpose are less likely to be hospitalized for conditions that can be effectively treated on an outpatient basis.

We are aware of one prior study that found higher purpose to be associated with less self-reported hospitalization using data from the Health and Retirement Study (21). The present results extends knowledge about the association by ascertaining information about hospitalization using Medicare claims data, a method that is independent of recall which can be inaccurate in older people (22-26).

The factors underlying the association of higher purpose with fewer hospitalizations are uncertain. Purpose has been associated with better health as manifested by lower risk of conditions such as coronary heart disease (19), stroke (15), cerebral infarction (16), depression (13,14), disability (29), and dementia (17), and adjustment for vascular health and depression in the present analyses reduced the association of purpose with hospitalization, consistent with the idea that people with a high sense of purpose are less likely to be hospitalized than people with a low sense of purpose partly because they are healthier. However, no association was observed with non-ACSC hospitalizations, suggesting that purpose has a somewhat selective association with hospitalization, perhaps involving more effective management of conditions with high care demands. It is also possible that purpose effects are partly due to factors related to purpose that were not controlled for in analyses such as spirituality (43), quality and quantity of social networks (44), and sleep (45). Another consideration is that older people face multiple challenges, particularly declining health and functional capacity, personal loss, and other external factors which may have contributed to the decline in purpose that was observed in the present study. A key component of resilience in the face of adversity is making meaning out of challenging circumstances and growing as a result (46). This suggests that even with health factors controlled, those with higher in purpose are likely to be more resilient and to respond more adaptively to age related illness, functional loss, and other challenges than those with lower purpose. Finally, although purpose predicted subsequent hospitalization, we cannot rule out the possibility that hospitalization and other health related factors are influencing sense of purpose.

If purpose is contributing to risk of hospitalization, enhancing purpose in life might reduce hospitalization in older people. Importantly, purpose in life is modifiable, and treatments that target purpose and other aspects of well-being are available including mindfulness-based stress reduction (47), positive narrative interventions (48,49), promotion of meaningful social roles (50), and forms of psychotherapy (51). Further research on the feasibility and efficacy of such interventions is needed, as well as research to clarify the potential personal and societal, including economic, implications of such interventions.

Strengths and limitations of these data should be noted. Purpose in life was assessed with a standard psychometrically established scale. The rate of participation in follow-up was high, making it less likely that results were biased by selective attrition. Hospitalization was determined from Medicare claims data rather than participant report and potentially preventable hospitalizations were analyzed separately. The association of purpose with hospitalization was observed for purpose measured at baseline and follow-up, suggesting that the results are reliable. The main limitation is that participants were selected and predominantly White; research in more diverse groups is needed. In addition, there were few non-ACSC hospitalizations during the observation period which may have limited our power to detect an association of purpose with such hospitalizations.

In summary, in a prospective observational study, we found that a stronger sense of purpose in life was associated with less subsequent hospitalization for conditions that can be effectively managed on an outpatient basis. Better understanding of the bases and direction of the association of purpose in life with hospitalization and psychosocial factors that may modify it could suggest novel strategies for reducing health care expenditure.

Highlights.

In older adults, higher sense of purpose in life was associated with lower odds of subsequent hospitalization.

The association of purpose with hospitalization was stronger for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions and was weaker after controlling for common chronic conditions.

Results suggest that higher level of purpose in life is associated with lower odds of subsequent hospitalization for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG17917, R01AG34374, R01AG33678) and the Illinois Department of Public Health

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Facts and Figures 2008. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Oct, 2010. Healthcare cost and utilization poject (Section 1) www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/factsandfigures/2008/section1_TOC.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;51:451–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, et al. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004;292:2115–2124. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.17.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill TM, Allore HG, Gahbauer EA, et al. Change in disability after hospitalization or restricted activity in older persons. JAMA. 2010;304:1919–1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehlenbach WJ, Hough CL, Crane PK, et al. Association between acute care and critical illness hospitalization and cognitive function in older adults. JAMA. 2010;303:763–770. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson RS, Hebert LE, Dong X, et al. Cognitive decline after hospitalization in a community population of older persons. Neurology. 2012;78:950–956. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824d5894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorina Y, Pratt LA, Kramaro EA, et al. National health statistics reports. no 84. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. Hospitalization, readmission, and death experience of non-institutionalized Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries aged 65 and older. https://www.cdc.goc/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr084.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubzansky LD, Kubzanisky PE, Maselko J. Optimism and pessimism in the context of health: Bipolar opposites or separate construct? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 30:943–956. doi: 10.1177/0146167203262086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steptoe A, Dockray S, Wardle J. Positive affect and psychobiological processes relevant to health. Journal of Personality. 2009;77:1474–1776. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00599.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers So Psychol. 1989;57:1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sone T, Nakaya N, Ohmori K, Shimazu T, Higashiguchi M. Sense of life worth living (Ikigai) and mortality in Japan: Ohsaki study. Pschosomatic Medicine. 2008;70:709–715. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817e7e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Buchman AS, et al. Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:574–579. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181a5a7c0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryff CD, Keyes CL. The structure of psychological well-being revisted. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wood AM, Joseph S. The absence of positive psychological (eudemonic) well-being as a risk factor for depression: A ten year cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;122:213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim ES, Sun JK, Park N, et al. Purpose in life and reduced incidence of self-reported stroke in older adults: The Health Retirement Study. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74:427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu L, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, et al. Purpose in life and cerebral infarcts in community dwelling older persons. Stroke. 2015;46:1071–1076. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, et al. Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:304–310. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman EM, Ryff CD. Living well with medical comorbidities: a biopsychosocial perspective. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67:535–544. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim ES, Sun JK, Nansook P. Purpose in life and reduced risk of myocardial infarction among older U.S. adults with coronary heart disease: a two-year follow-up. J Behav Med. 2013;36:124–133. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9406-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Segawa E, Begeny CT, Anagnos SE, Bennett DA. The influence of cognitive decline on well-being in old age. Psychol Aging. 2013;28:314–321. doi: 10.1037/a0031196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim ES, Strecher VJ, Ryff CD. Purpose in life and use preventive health care services. PNAS. 2014;111:16331–16336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414826111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallihan DB, Stump TE, Callahan CM. Accuracy of self-reported health services use and patterns of care among urban older adults. Medical Care. 1999;37:662–670. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Donnell CJ, Glynn RJ, Field TS, et al. Misclassification and under-reporting of acute myocardial infarction by elderly persons: implications for community-based observational studies and clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:745–751. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raina PVTR, Wong M, Woodward C. Agreement between self-reported and routinely collected health-care utilization data among seniors. Health Services Research. 2002;37:751–774. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolinsky FD, Jones MP, Ullrich F, Lou Y, Wehby GL. The concordance of survey reports and Medicare claims in a nationally representative longitudinal cohort of older adults. Med Care. 2015;52:462–468. doi: 10.1097/MLR.000000000000120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolinsky FD, Jones MP, Ullrich F, Lou Y, Wehby GL. Cognitive function and the concordance between survey reports and Medicare claims in a nationally representative cohort of older adults. Med Care. 2015;53:455–462. doi: 10.1097/MLR.000000000000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Mendes de Leon CF, Wilson RS. The Rush Memory and Aging Project: study design and baseline characteristics of the study cohort. Neuroepidemiol. 2005;25:163–175. doi: 10.1159/000087446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview andfindings from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:646–663. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, et al. Correlates of life space in a volunteer cohort ofolder adults. Exp Aging Res. 2007;33:77–93. doi: 10.1080/03610730601006420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Bennett DA. Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident disability among community-dwelling older persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:1093–1102. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d6c259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, et al. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA. 1995;274:305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oster A, Bindman AB, et al. Emergency department visits for ambulatory care sensitive conditions: insights into preventable hospitalizations. Med Care. 2003;41:198–207. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000045021.70297.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phelan EA, Borson S, Grothaus L, et al. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA. 2012;307:165–172. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCall N, Harlow J, Dayhoff D. Rates of Hospitalization for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions in the Medicare+Choice Population. Health Care Financ Rev. 2001;22:127–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Assessment of lifetime participation in cognitively stimulating activities. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2003;25:634–642. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.634.14572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Krueger KR, Hoganson G, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, et al. Early and late life cognitive activity and cognitive systems in old age. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005;11:400–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Yang J, James BD, Bennett DA. Early life instruction in foreign language and music and incidence of mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology. 2015;29:292–302. doi: 10.1037/neu0000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, et al. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 1993;5:179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale = a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hadden WC, Rockswold PD, et al. Increasing differential mortality by educational attainment in adults in the United States. doi: 10.2190/HS.38.1.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson RS, Scherr PA, Hoganson G, et al. Early life socioeconomic status and late life risk of Alzheimer's disease. Neuroepidemiol. 2005;25:8–14. doi: 10.1159/000085307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capuano AW, Dawson JD. The trend odds model for ordinal data. Stat Med. 2013;32:2250–2261. doi: 10.1002/sim.5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kashdan TB, Nezlek JB. Whether, when, and how is spirituality related to well-being? Moving beyond single occasion questionnaires to understanding daily process. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2012;38:1523–1535. doi: 10.1177/0146167212454549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Influence of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2000;15:187–224. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim ES, Hershner SD, Strecher VJ. Purpose in life and incidence of sleep disturbances. J Behav Med. 2015;38:590–597. doi: 10.1007/s10865-015-9635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryff CD. Self-Realization and Meaning Making in the Face of Adversity: A Eudaimonic Approach to Human Resilience. J Psychology Afr. 2014;24:1–12. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2014.904098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moss AS, Reibel DK, Greeson JM, et al. An adaptive mindfulness-based stress reduction program for elders in a continuing care retirement community: quantitative and qualitative results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;34:518–538. doi: 10.1177/0733464814559411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedman EM, Ruini C, Foy R, et al. Lighten UP! A community-based group intervention to promote psychological well-being in older adults. Aging Mental Health. 2015;13:1–7. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1093605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cesetti G, Vescovelli F, Ruini C. The promotion of well-being in aging individuals living in nursing homes: a controlled pilot intervention with narrative strategies. Clin Gerontol. 2017 Feb 8;:1–12. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2017.1292979. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heaven B, Brown LJ, White M, et al. Supporting well-being in retirement through meaningful social roles: systematic review of intervention studies. Milibank Q. 2013;9:222–287. doi: 10.1111/milq.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frankl VE. Man's search for meaning. Boston: Beacon Press; 1959. [Google Scholar]