Abstract

Purpose

To provide clinically useful gadolinium-free whole-body cancer staging of children and young adults with integrated positron emission tomography / magnetic resonance (PET/MR) imaging in less than 1 h.

Procedures

In this prospective clinical trial, 20 children and young adults (11–30 years old, 6 male, 14 female) with solid tumors underwent 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose ([18F]FDG) PET/MR on a 3T PET/MR scanner after intravenous injection of ferumoxytol (5mg Fe/kg) and [18F]FDG (2–3 MBq/kg). Time needed for patient preparation, PET/MR image acquisition and data processing was compared before (n = 5) and after (n = 15) time-saving interventions, using a Wilcoxon test. The ferumoxytol-enhanced PET/MR images were compared with clinical standard staging tests regarding radiation exposure and tumor staging results, using Fisher's exact tests.

Results

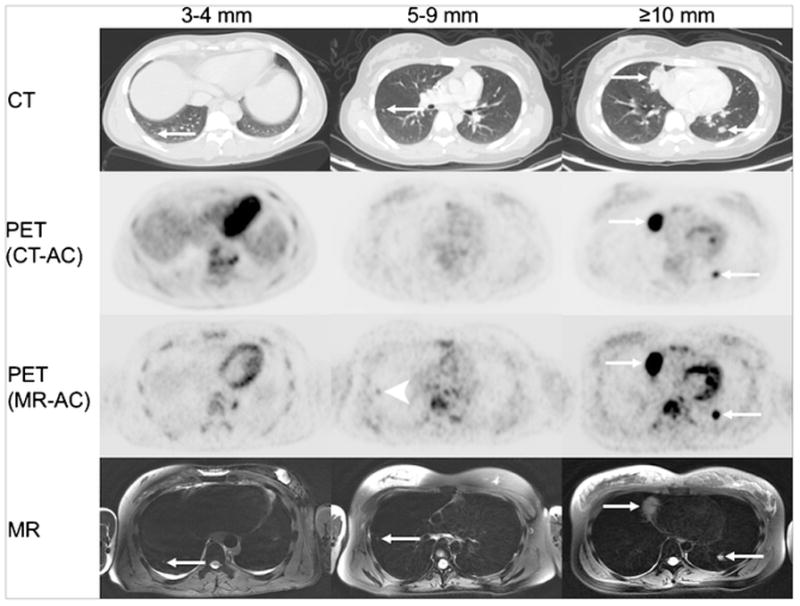

Tailored workflows significantly reduced scan times from 36 to 24 min for head to mid thigh scans (p < 0.001). These streamlined PET/MR scans were obtained with significantly reduced radiation exposure (mean 3.4 mSv) compared to PET/CT with diagnostic CT (mean 13.1 mSv; p = 0.003). Using the iron supplement ferumoxytol “off label” as an MR contrast agent avoided gadolinium chelate administration. The ferumoxytol-enhanced PET/MR scans provided equal or superior tumor staging results compared to clinical standard tests in 17 out of 20 patients. PET/MR had comparable detection rates for pulmonary nodules equal or greater 5 mm (94% vs. 100%), yet detected significantly fewer lung nodules compared to PET/CT for smaller nodules (20% vs 100%) (p = 0.03). [18F]FDG-avid nodules were detected with slightly higher sensitivity on the PET of the PET/MR compared to the PET of the PET/CT (59% vs 49%).

Conclusion

Our streamlined ferumoxytol-enhanced PET/MR protocol provided cancer staging of children and young adults in less than 1 h with equivalent or superior clinical information compared to clinical standard staging tests. The detection of small pulmonary nodules with PET/MR needs to be improved.

Keywords: Positron-Emission Tomography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Nanoparticles, Cancer, Pediatrics

Introdcution

Children and young adults with a newly diagnosed malignant tumor often have to undergo multiple imaging tests, such as an ultrasound, x-rays, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and/or a bone scan, in order to determine the extent of the primary tumor and metastases in the whole body [1–3]. Results of these staging tests help to estimate prognosis and plan the most appropriate therapy. Recent developments aim to provide “one stop” cancer staging in one imaging session – and thereby, improve time-and cost-efficiency, reduce stress for the family and avoid repetitive anesthesia.

2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose ([18F]FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) with integrated computed tomography (CT) has been established as a “one stop” whole body staging test for pediatric patients with lymphomas [4–5]. [18F]FDG PET/CT has been also found valuable for the detection of lung, bone and nodal metastases in pediatric patients with malignant sarcomas [6–7]. However, due to the limited soft tissue contrast of CT, patients with sarcomas often have to undergo an additional MR scan to determine the location and extent of their primary tumor. In either case, [18F]FDG PET/CT is associated with considerable radiation exposure, a particular concern for children with cancer.

Integrated [18F]FDG PET/MR is an attractive alternative to [18F]FDG PET/CT [8] and whole body CT [9–10]. Since it uses MR data for anatomical co-registration of [18F]FDG PET data [11–12], [18F]FDG PET/MR is associated with significantly lower radiation exposure compared to [18F]FDG PET/CT [13]. In addition, in patients with sarcomas, [18F]FDG PET/MR could potentially reduce a current “two stop” staging approach (MRI plus PET/CT) to a “one stop” staging approach. However, the long acquisition times of current [18F]FDG PET/MR tumor staging protocols have generated a major hurdle for pediatric applications: Current PET/MR cancer staging protocols take 1–2 h [8, 14], while a standard PET/CT scan takes about 15–20 min [15]. Furthermore, recent reports about gadolinium deposition in the brain has raised concerns about the safety of gadolinium chelates for MR imaging scans [16]. The goal of our study was to provide gadolinium-free cancer staging of children and young adults with integrated [18F]FDG PET/MR imaging in less than 1 h. To accomplish this goal, we utilized the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved iron supplement ferumoxytol (Feraheme) “off label” as a MR contrast agent, we mapped the workflow for our pediatric [18F]FDG PET/MR exams, applied time-saving interventions and compared tumor staging results with standard staging tests.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population

This prospective, non-randomized, health insurance portability and accountability act (HIPAA)-compliant clinical trial was approved by our institutional review board and was performed under an investigator-initiated investigational new drug (IND) application for “off label” use of ferumoxytol as a contrast agent (IND 111,154). From May 2015 until December 2016, we recruited 20 cancer patients (age 18.9 ± 5.5 years; range:11–30) with the following inclusion characteristics: (1) age 8 to 30 years, (2) solid extracranial tumor (3) willingness to participate in a research PET/MR scan. Exclusion criteria comprised: (1) central nervous system tumor, (2) MRI contraindications, (3) hemosiderosis or hemochromatosis, (4) history of any allergies to contrast agents or any severe allergies to other substances or (5) pregnancy. We recruited 14 females (mean age 19.8 ± 4.8 years; range: 14–29) and 6 males (mean age 16.8 ± 2.6 years; range: 11–30; Supplemental Table 1) with lymphoma (n = 7), Ewing sarcoma (n = 3), osteosarcoma (n=4) or soft tissue sarcoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, ovarian steroid cell tumor (a sex cord-stromal tumor of the ovary with malignant potential, accounting for less than 0.1% of all ovarian tumors) [17], hepatocellular carcinoma, osteoma or recurrent Wilms tumor (n = 1 each).

PET/MR: Technology and Streamlining the Workflow

All patients fasted for at least 4 h before the scan (mean pre-scan blood glucose 84 mg/dl; range: 61–107 mg/dl). The patients had the option to receive the PET/MR directly after their clinical PET/CT scan (single 1[18F]FDG dose: 5 Megabequerel (MBq) per kg bodyweight; containing of one single contrast enhanced CT for both attenuation correction and diagnostic purposes. This technique is called an “expert mode” CT. It is performed in “arms up” position and includes a low dose CT of the head, followed by a diagnostic breath-hold contrast-enhanced CT of the neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis, and a low dose CT of the legs). Alternatively, patients could choose to receive a PET/MR scan on a separate day than their PET/CT scan. In this case, a second, lower radiotracer dose was administered for the PET/MR (the lower dose was possible due to the higher sensitivity of the PET detector in our PET/MR system). All patients chose the second option and underwent an integrated PET/MR scan (3T Signa PET/MR, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA) at 1–72 h after intravenous infusion of ferumoxytol (Feraheme® Injection, AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Waltham, USA; 5 mg Fe/kg bodyweight, diluted 1:4 in saline, administered over 15 min) and 45 min (mean 47.1 ± 16.0 min) after [18F]FDG infusion (2–3 MBq/kg; dose mean: 173.2 ± 68.1 MBq). One patient did not receive ferumoxytol due to an allergic reaction (hives) to CT contrast agent the day before the PET/MR.

To set up a time-efficient protocol, we considered the PET data acquisition the time-limiting step. We first prescribed axial PET acquisition slabs (25 cm axial FOV; 4 min per slab) for whole body staging and filled these slabs with axial in and out-of phase T1-weighted Liver Acquisition with Volume Acquisition (LAVA) (3D Fast Spoiled Gradient Echo) sequences for attenuation correction, higher resolution LAVA sequences for anatomical co-registration, and diffusion-weighted (DWI) sequences (Table 1). We then added T1- and T2-weighted Fast Spin Echo (FSE) sequences in appropriate orientations for local staging of the primary tumor. We adjusted the FOV to the size of the patient. Applied FOVs ranged from 48 cm for the lungs and abdomen, to 24 cm for the extremities and to 18 cm for the scapula. We added axial sequences for pulmonary nodule evaluation: In addition to the above mentioned LAVA sequence, we scanned the chest with an axial T2-weighted FSE sequence and an axial periodically rotated overlapping parallel lines with enhanced reconstruction (PROPELLER) sequence (Table 1). We monitored each patient with a breathing belt. The axial and coronal LAVA sequences were acquired in a 16 s breath-hold in mid-expiration phase. The T2 PROPELLER was acquired during free breathing with special regards to younger children where respiratory gating or breath-holds are difficult and exhausting for the patient.

Table 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging pulse sequence parameters

| Pulse Sequence Parameter | Axial Dixon | Axial LAVA | Axial DWI | Axial/Coronal T2 FSE | Axial PROPELLER |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition Time (min) | 0:18 | 0:16 | 1:47 | 3:42 | 5:48 |

| Echo Time (ms) | 1.1;2.3 | 1.7 | 56 | 64 | 119 |

| Repetition Time (ms) | 4.2 | 4.2 | 7824 | 4000 | 12500 |

| Matrix Size | 256x128 | 320x224 | 80x128 | 320x224 | 384x384 |

| Slice Thickness (mm) | 5.2 | 3.4 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| Field of View (cm) | 50 | 48 | 40 | 38 | 48 |

| Flip Angle (degrees) | 5 | 15 | 90 | 111 | 110 |

| b-value (s/mm2) | - | - | 50, 600 | - | - |

DWI = Diffusion weighted imaging, LAVA = Liver Acquisition with Volume Acquisition, PROPELLER = Periodically rotated overlapping parallel lines with enhanced reconstruction, FSE= Fast spin echo

The PET data was reconstructed using a 3D time of flight iterative ordered subsets expectation maximization algorithm (24 subsets, 3 iterations, temporal resolution = 400 ps, matrix 256 × 256; voxel size 2.8 × 2.8 × 2.8 mm), accounting for attenuation from coils and patient cradle.

We mapped the workflow according to three main components: (1) Patient preparation time, (2) PET/MR scan time and (3) Post-processing time (Figure 1a). We measured the time for each step in this workflow and created questionnaires to evaluate satisfaction with the PET/MR procedure by patients and radiologists (Supplemental Fig. 1a and 1b). Based on initial results from the first five patients, we identified and applied time saving interventions, and then re-evaluated the same metrics in the next 15 patients.

Figure 1.

PET/MR workflow for Cancer Staging of Children and Young Adults at our institution: a Sequence of PET/MR workflow steps during patient preparation, PET/MR scan, and image processing. b Duration of different steps of the workflow before and after time saving interventions. Data are displayed as means and standard deviations of 5 PET/MR studies before and 15 PET/MR studies after time saving interventions. * indicates significant differences between pre and post intervention duration.

Diagnostic Value of PET/MR for Pediatric Cancer Staging

Several studies have shown that PET/MR and PET/CT have comparable sensitivities for tumor detection [8, 18–20]. This is not surprising as PET is more sensitive than CT alone for tumor staging [21–22]. To evaluate, whether our streamlined PET/MR protocol provided equal or improved diagnostic information compared to clinical standard staging tests, we compared our PET/MR data with clinical standard staging tests, obtained within 7 days before or after the PET/MR scan. These included an integrated [18F]FDG PET/CT (n = 7 patients with lymphoma and n = 1 patient with nasopharyngeal carcinoma, osteosarcoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma, respectively; Discovery 690, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA) and a combination of local MRI (Discovery 750, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA), diagnostic CT (Somatom Dual Flash; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) and bone scan (Infinia, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA) in n=11 patients with other tumors, described above. Of note, the PET/CT scan at our institution includes a diagnostic CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, obtained in the expert mode [23]. A board-certified nuclear medicine physician (A.Q.) and a board-certified pediatric radiologist (H.E.D.) recorded in consensus, if PET/MR and standard staging tests provided concordant information (yes/no) regarding: (1) organ of origin (primary tumor), (2) tumor necrosis, (3) infiltration of adjacent organs, (4) encasement of vessels, nerves or ureters, (5) primary tumor diagnosis, (6) lymph node involvement/metastases, (7) pulmonary metastases, (8) other metastases. Finding(s) on PET/MR, not seen on standard imaging tests were recorded as discordant for PET/MR and vice versa. Clinical standard follow up imaging over at least 6 months and histology were employed as standard of reference.

Radiation Dose Calculation

The radiation exposure due to the PET/MR exam was compared with the radiation exposure due to PET/CT and CT exams for tumor staging in our patients: The effective dose from the [18F]FDG injection was calculated using the age-specific conversion factors published by the International commission on radiological protection [24]. To calculate radiation exposure from CT exams, the size specific conversion factors from the dose length product (DLP) to effective dose were calculated for each patient. The lateral length across the mid-liver region was measured on axial CT images, multiplied with established conversion factors [25] and fitted against the lateral width of five phantoms using an exponential equation and Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, USA). The lateral width of each patient was considered to calculate the size specific conversion factor. Lastly, effective dose was obtained by multiplying the DLP and calculated conversion factor.

Lung Nodule Detection

A pediatric radiologists (L.L., 5 y of experience) and a fourth year radiology resident (A.T.) counted pulmonary nodules on PET/MR and PET/CT studies, in a random order and with an interval of at least 2 months between the readings to avoid recall bias. Since current clinical treatment protocols for sarcomas change management for multiple pulmonary nodules ≥ 3 mm or a single nodule ≥ 5 mm [26], we categorized pulmonary nodules with sizes of 1–2 mm, 3–4 mm, 5–9 mm and ≥ 10 mm.

As a first step, the reviewers compared the number and size of pulmonary nodules on LAVA, T2-FSE and T2-PROPELLER sequences. The most sensitive sequence was then used for comparisons of PET/MR and PET/CT. Finally, the reviewers evaluated in consensus, how many pulmonary nodules were missed due to limited anatomical resolution (not visible) or artifacts (obscured).

Statistical Analyses

Time needed for patient preparation, PET/MR image acquisition and data processing was compared before (n=5) and after (n=15) time-saving interventions, using a paired or unpaired exact Wilcoxon test. Comparison of our PET/MR images with clinical standard staging tests regarding radiation exposure and tumor staging results were compared with a Fisher's exact tests. All statistical analyses were done with Stata Release 14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, USA), using a significance level of 0.05.

Results

PET/MR: Technology and Streamlining the workflow

To streamline patient preparation times, we provided patients with a screening form in advance of their appointment, we explained the imaging procedure in detail during the [18F]FDG uptake time and we reduced the waiting time between [18F]FDG injection and entering the scanner room from 60 to 45 min since voiding and coiling of the patient accounted for 15 min. To minimize the patient’s time in the scanner, we instructed patients to practice breath-hold maneuvers during the FDG uptake time; we used an optimized, tumor-type tailored imaging protocol as described above and we ensured real-time scan checks by a radiology resident; Image acquisition time and repetitions decreased with increasing experience of the imaging team. PET and MR data could only be fused on the main PET/MR console and was initially delayed due to interference with other scans. We accelerated the fusion process by scheduling dedicated time for it. To accelerate data transfer to the picture archiving and communication system (PACS), we separated images under two accession numbers: (1) Diagnostic scans containing axial and coronal contrast-enhanced LAVA images of the whole body (similar to a whole body CT scan) with and without [18F]FDG PET, axial DWI, axial attenuation-corrected [18F]FDG PET, maximum intensity projection of FDG-PET, axial propeller sequences of the lungs with and without [18F]FDG PET and dedicated sequences of the tumor with and without [18F]FDG PET and (2) Uncorrected [18F]FDG PET data, Dixon sequences for attenuation correction and any secondarily postprocessed images. The first accession number could be used for a timely report while the second accession number could be left open for several hours to allow later addition of post-processed data sets. To optimize image data review by the radiologist and clinicians, we labeled sequences in a consistent manner and fused axial scans from subsequent slabs such that it was possible to scroll through all images of the same sequence, i.e. from head to toe. This improved radiologist satisfaction with sequence identification and exam loading time significantly (p=0.044 and 0.008, respectively; Supplemental Fig. 1c). Patient satisfaction was high and not significantly different before and after time saving interventions (Supplemental Fig. 1d). ±10844 images and took 23 ± 8 min for patient preparation, 36 ± 6 min for head to mid thigh PET/MR image acquisition and 8.2 ± 7.2 h for data post-processing and PACS transfer (Fig. 1b). After the above mentioned interventions, diagnostic scans consisted of 4938 ± 1325 images and took 11 ± 6 min for patient preparation, 24 ± 4 min for head to mid thigh PET/MR image acquisition and 1.2 ± 0.3 h for data post-processing and PACS transfer. Acquisition times for additional sequences through the primary tumor and the lungs ranged from approximately 20 to 30 min. The time savings of 12 min for patient preparation, 12 min for the PET/MR scan and 7 h for postprocessing were statistically significant (p = 0.011; p = 0.001; p = 0.007, respectively). Exam loading time on the PACS system also significantly decreased from 6 to 1 min (p = 0.012)

Diagnostic Value of PET/MR for Pediatric Cancer Staging

The radiation exposure of PET/MR studies (mean: 3.4 mSv) was significantly lower compared to PET/CT (mean: 13.1 mSv; p = 0.0033). There were no adverse events due to the ferumoxytol injection.

Ferumoxytol provided long-lasting vascular enhancement, which provided excellent vessel and tumor delineation for the duration of the entire scan (Fig. 2–5). The ferumoxytol-enhanced PET/MR scans provided equal or superior tumor staging results compared to clinical standard tests in 17 out of 20 patients. Nine of the 20 patients had concordant diagnostic findings on PET/MR and standard staging tests (Table 2), including six of the nine patients with lymphomas (Fig. 2), two with osteosarcomas, and one patient with steroid cell ovarian tumor. Eight patients had discordant findings on the PET/MR, not seen on the standard imaging test (Table 2): This included a soft tissue sarcoma with hypermetabolic tumor areas close to renal vessels (Fig. 3), a Ewing’s sarcoma of the humerus which could be better delineated from surrounding edema (Fig. 4), and a recurrent Wilms tumor which could be better delineated from adjacent bowel (Fig. 5). This information was considered clinically important for surgical resection. Three patients showed better tumor delineation on PET/MR and better pulmonary nodule detection on CT and would therefore likely have benefitted from a “triple” scan. Six patients had additional findings on standard imaging tests, not seen on the PET/MR. These were all instances of pulmonary nodules. A detailed description of the findings for each patient according to our criteria is listed in Supplemental Table 2a and superior PET/MR findings and the clinical relevance are listed in Supplemental Table 2b.

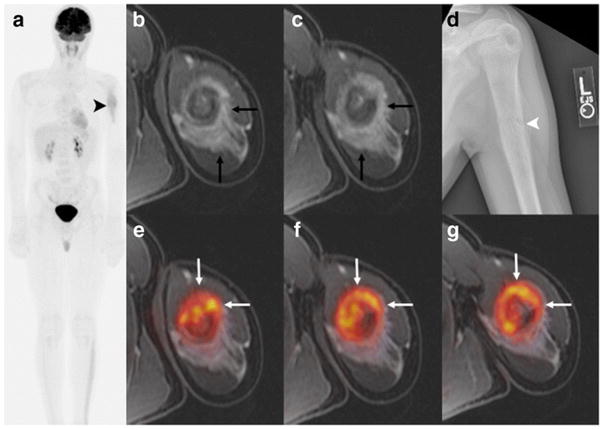

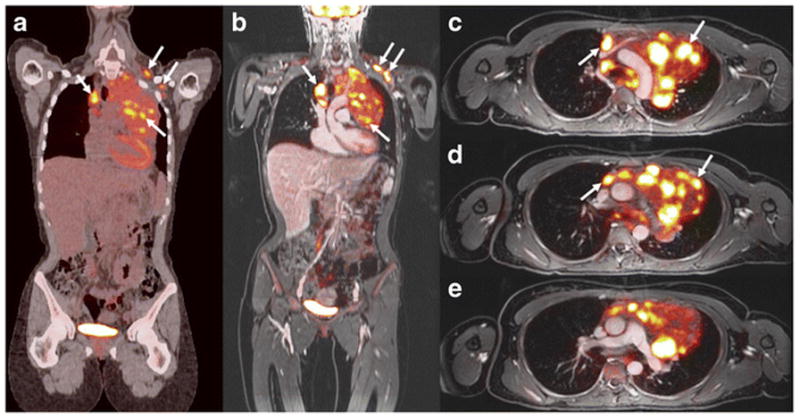

Figure 2.

[18F]FDG PET/CT and PET/MR in a 23-year-old girl with Hodgkin Lymphoma: a Coronal PET/CT shows mediastinal and left infraclavicular [18F]FDG-avid lymph nodes (white arrows). b–e Corresponding coronal and axial T1-weighted LAVA scan (TR/TE/Flip angle: 4.2/1.7/15) after intravenous ferumoxytol injection with superimposed [18F]FDG PET scan demonstrates mediastinal and infraclavicular [18F]FDG-avid lymph nodes (white arrows). The findings on PET/CT and PET/MR are concordant.

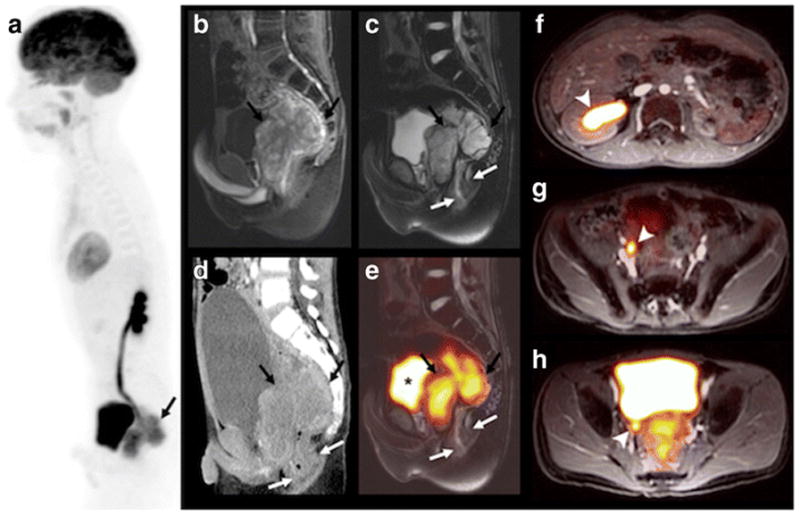

Figure 5.

PET/MR and CT findings in an 11-year-old boy with status post resection of a Wilms tumor of the left kidney and recurrent tumor in the pelvis. This patient with a single, mildly hydronephrotic kidney benefitted from omission of nephrotoxic contrast agent for the scan. a Sagittal maximum intensity projection [18F]FDG PET shows a hypermetabolic mass behind the bladder (black arrow), b sagittal T1-weighted ferumoxytol-enhanced LAVA scan (TR/TE/Flip angle: 4/1.7/15) shows T1-enhancement of the tumor, but not the bladder. c, e T2-weighted ferumoxytol-enhanced FSE scan (TR/TE/Flip angle: 4634/69.2/142) without and with superimposed 18F-FDG PET, shows better tumor delineation of retrovesical tumor (black arrows) from the adjacent rectum (white arrows) and bladder (*), compared to d sagittal contrast-enhanced CT. (f–h) Axial T1-weighted ferumoxytol-enhanced LAVA scans with superimposed [18F]FDG PET (TR/TE/flip angle: 4.2/1.7/15) nicely shows enhancing vessels and a dilated [18F]FDG filled ureter and renal pelvis (white arrowhead) due to tumor obstruction.

Table 2.

Identical or additional diagnostic findings on PET/MR compared to standard imaging tests

| Additional Finding(s) on PET/MR | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Additional Finding(s) on | Yes | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Standard Imaging Test | No | 5 | 9 | 14 |

| Total | 8 | 12 | 20 | |

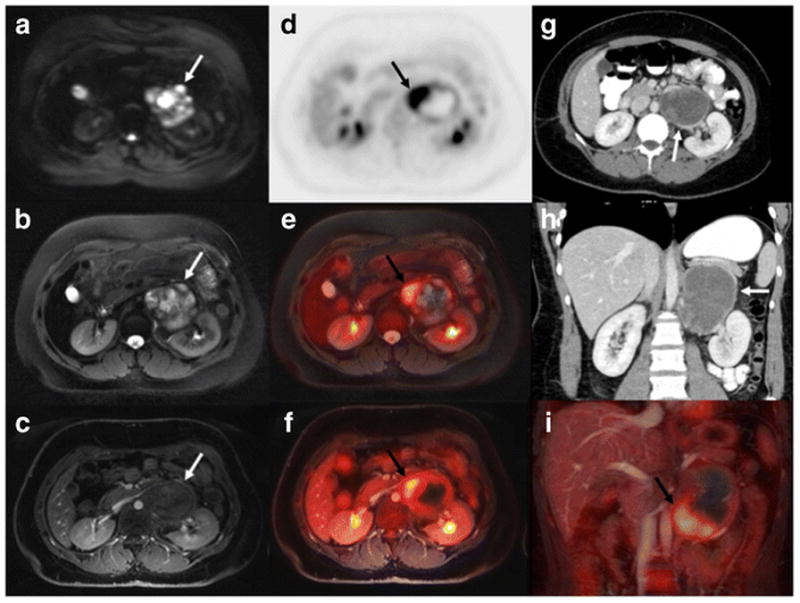

Figure 3.

[18F]FDG PET/MR and CT findings in a 25-year-old female with soft tissue sarcoma in the left retroperitoneum (arrows). a Axial diffusion weighted imaging (TR/TE/b-value: 7770/56.1/50,600) shows restricted diffusion (white arrow) in the tumor, b axial T2 PROPELLER (TR/TE/Flip angle: 8000/95.8/142) shows inhomogeneous hyperintense tumor signal; c ferumoxytol-enhanced T1-weighted LAVA scan (TR/TE/Flip angle: 4.2/1.7/15) shows close relation between the tumor and renal vessels. d Axial [18F]FDG PET, e 1[18F]FDG PET superimposed on T2-weighted FSE scan and f [18F]FDG PET superimposed on T1-weighted LAVA scan show that the tumor contains hypermetabolic medial and caudal areas (black arrow). g, h Axial and coronal CT shows a rather featureless, slightly inhomogeneous mass (white arrow); (i) Coronal [18F]FDG PET superimposed on T1-weighted LAVA scan again shows the hypermetabolic caudal tumor part (black arrow). At surgery, this anterior and caudal tumor part was found to be adherent to adjacent vascular structures.

Figure 4.

[18F]FDG PET/MR and MR only findings in a 14-year-old boy with Ewing Sarcoma of the left humerus. a Maximum intensity projection [18F]FDG PET of the whole-body showing increased uptake in the left humerus (black arrowhead). No skip lesions or metastases are noted. b, c Axial T1-weighted ferumoxytol-enhanced LAVA scan (TR/TE/Flip angle: 4.2/1.7/15) with extensive perilesional contrast-enhanced oedema (black arrow), due to a pathological fracture (white arrowhead), d confirmed on plain radiograph. e–g Axial [18F]FDG PET superimposed on T1-weighted ferumoxytol-enhanced LAVA scan shows improved delineation of the tumor (white arrow) from enhancing peritumoral edema.

Lung Nodule Detection

The sum of all staging tests at baseline and follow up imaging over at least 6 months were employed as standard of reference and detected a total of 148 pulmonary nodules in nine patients. Eight of the nine patients with pulmonary nodules had one to eight pulmonary nodules; while the ninth patient had a total of 117 nodules (Table 3a). The T1-weighted LAVA sequence detected fewer pulmonary nodules (53) compared to the T2-FSE (107) and T2-PROPELLER (107) sequences. The T2-FSE sequence had better vessel contrast yet showed more pronounced breathing artifacts compared to the T2-PROPELLER sequence (Supplemental Fig. 2). Therefore, the T2-PROPELLER sequence was chosen for pulmonary nodule staging in our PET/MR protocol.

Table 3a.

Total pulmonary nodules detected by patient and modality

| ID | CT of PET/CT | PET of PET/CT | MRI of PET/MR | PET of PET/MR | MRI retro |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 117 | 56 | 91 | 67 | 100 |

| 3 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 9 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 10 | 4 | - | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 14 | 5 | - | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 15 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | 2 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

ID = Patient Identification Number; CT = Computed Tomography; PET/CT = Integrated Positron Emission Tomography with CT; MRI = Magnetic Resonance Imaging; PET/MR = Integrated Positron Emission Tomography with Magnet Resonance Imaging

We compared our PET/MR images with standard PET/CT images for pulmonary nodule staging. The CT-part of the PET/CT revealed 144 total nodules, including 56 ≥ 10mm, 48 between 5–9mm, 32 between 3–4mm and 12 < 3mm respectively. The MR-part of the PET/MR detected 107 total nodules with 56 ≥ 10mm, 42 between 5–9mm, 8 between 3–4mm and 1 < 3mm in size, respectively. Considering nodules ≥ 5 mm, detection was 100% (104/104) for PET/CT and 94% (98/104) for PET/MR, while for nodules < 5 mm, detection was 100% (44/44) for PET/CT and only 20% (9/44) for PET/MR (Fig. 6, Table 3b).

FIGURE 6.

Detection of pulmonary nodules with PET/CT and PET/MR. Representative axial CT, PET (CT-attenuation corrected), PET (MR-attenuation corrected) and axial T2-weighted PROPELLER (TR/TE/Flip angle: 12500/119/110) images of pulmonary nodules (white arrows) of different sizes. Improved detection of a 5 mm pulmonary nodule on PET scan of a PET/MR compared to PET scan of a PET/CT (white arrowhead).

Table 3b.

Total pulmonary nodules detection by size and modality

Number of pulmonary nodules detected on CT only, PET-CT (i.e. FDG-avid nodules on PET/CT), PROPELLER MRI only and PET/MR. Column MRI retro represents nodules that were detected with a retrospective approach (i.e. looking for nodules on MRI seen on CT). Two experienced reviewers assessed all imaging studies in consensus through a prospective approach with an interval of at least two months between evaluations of different imaging modalities to avoid recall bias.

| CT of PET/CT | PET of PET/CT | Combined PET/CT | MRI of PET/MR | PET of PET/MR | Combined PET/MR | MRI retro | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodule size (mm) | |||||||

| > 10 | 56 | 52 | 56 | 56 | 54 | 56 | 56 |

| 5–9 | 48 | 9 | 48 | 42 | 18 | 42 | 45 |

| 3–4 | 32 | 0 | 32 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 18 |

| 1–2 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Nodule number | |||||||

| Total | 148 | 61 | 148 | 107 | 72 | 107 | 121 |

| ≥ 5 mm | 104 | 61 | 104 | 98 | 72 | 98 | 101 |

| < 5 mm | 44 | 0 | 44 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 20 |

| % all nodules | 100 | 41 | 100 | 72 | 49 | 72 | 81 |

| % nodules ≥ 5 mm | 100 | 59 | 100 | 94 | 69 | 94 | 97 |

| % nodules <5mm | 100 | 0 | 100 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 45 |

We found more [18F]FDG-avid pulmonary nodules on the PET-scan of the PET/MR (n=72) compared to the PET-scan of the PET/CT (n = 61) (Table 3b), even though we applied a lower [18F]FDG dose (2–3 MBq/kg) for the PET/MR than for the PET/CT (5 MBq/kg). However, PET-data acquisition times for the PET/MR were longer (4 min per bed position) compared to the PET/CT studies (2–3 min per bed position). All nodules with a size of less than 5 mm did not show [18F]FDG-uptake on the corresponding PET-scan. There were no pulmonary nodules seen on the PET-scan and not seen on the corresponding MR.

To determine if nodules missed on the MR-part of the PET/MR were missed due to insufficient anatomical resolution, we checked if CT-visible nodules could be detected retrospectively on the corresponding MR. Supplemental Table 2 shows that our MR scans had an in plane resolution similar to the diagnostic chest CT scans. The difficulty in detecting nodules with a size of less than 5 mm arose from an inability to distinguish small nodules from small vessels, which could not be continuously followed on subsequent slides as in a CT scan as well as respiratory or cardiac motion artifacts (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Discussion

Our streamlined PET/MR protocol for gadolinium-free cancer staging of children and young adults provided superior tumor diagnosis and 74% reduction in effective dose compared to standard clinical imaging tests. Ferumoxytol-enhanced PET/MR provided clinically important detail about the primary tumor, and excellent detection of pulmonary nodules ≥ 5 mm. However, the detection of pulmonary nodules < 5 mm needs to be improved. Interestingly, the PET-part of the PET/MR outperformed the PET-part of the PET/CT in detecting [18F]FDG-avid pulmonary nodules.

Tailored PET/MR tumor staging is important for pediatric patients to ensure high image quality [27], time and cost efficiency [14, 28–29] and to minimize sedation times [30]. Previous PET/MR studies in pediatric patients evaluated the head to mid thighs with T2-weighted sequences in 60 and 45 min, respectively [8, 14]. We covered the same area in 24 min, using axial ferumoxytol-enhanced T1-weighted sequences, which are faster, provide better vessel delineation and anatomical information at a resolution that better matched a PET/CT scan [31]. To cover the whole body head to toe, we added additional beds depending on the patient height, which resulted in additional 4–12 min of scan time. However, this still resulted in shorter time intervals for the whole body and permitted the addition of dedicated high-resolution sequences for pulmonary nodule detection as well as dedicated imaging of the primary tumor without increasing the total scan time.

Previous PET/MR studies in adults [15, 32] and children [8, 18–20] used unenhanced Short Tau Inversion Recovery (STIR) and LAVA sequences for whole body anatomical orientation. Huellner et al. reported inferior tumor delineation on unenhanced STIR and LAVA images compared to PET/CT [15]. Protocols of the Children’s Oncology Group mandate a contrast-enhanced CT of the neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis for patients with lymphoma and a contrast-enhanced MRI for local staging of sarcomas. We used the blood pool agent ferumoxytol to achieve long lasting vascular and tissue contrast on T1-weighted LAVA MR scans throughout the entire duration of a PET/MR scan, i.e. whole body and primary tumor staging. This would be difficult to achieve with gadolinium-based contrast agents. Furthermore, Klenk et al showed that gadolinium based contrast agents are not necessary to evaluate a clinical PET/MR exam except for focal liver lesions [33]. In contrast to gadolinium based contrast agents, ferumoxytol provides improved delineation of tumor in liver, spleen and bone marrow [34–36]. Since phagocytic cells in the bone marrow take up iron, healthy marrow as well as reconverted hypercellular marrow exhibit a hypointense signal on T2-weighted sequences whereas malignant marrow appears hyperintense [34]. While gadolinium chelates have been associated with a risk of nephrogenic sclerosis [37] and gadolinium-deposition in the brain [16] ferumoxytol nanoparticles do not cross the blood brain barrier [38] and can be administered safely in patients with renal insufficiency [39–40]. However, both contrast agents have been associated with a risk of severe allergic reactions [39]. Although different numbers are found in the literature, the overall risk for a severe allergic reaction is very small [41].

In accordance with studies by Ponisio et al. [8], we noted a high concordance of PET/MR and PET/CT findings for patients with lymphoma. This justifies further studies in larger patient populations and potential future conversion to PET/MR staging for this patient population.

We found additional information on PET/MR imaging studies, not seen on PET/CT, CT or MRI, in 8 out of 20 patients (40%). This is in accordance with reports by Schaefer et al. [18], who reported that PET/MR changed initial staging compared to PET/CT in 25% of patients and Hirsch et al. [14], who reported improved delineation of hypermetabolic biopsy sites on PET/MR studies. Since pediatric cancers are rare, a single institution can only acquire limited experience. We initiated a consortium effort with the goal to pool these experiences towards disease-specific conclusions (i.e. who will benefit from a PET/MR as opposed to a PET/CT).

Our PET/MR protocol led to 74% reduced radiation exposure compared to standard clinical imaging tests. This is improved compared to previous studies (39% reduction), which used a dose of 5.55 MBq/kg body weight for the PET/MR and PET/CT [8]. We could administer a lower dose of 2–3 MBq/kg for the PET/MR because of longer PET data acquisition times. Minimized ionizing radiation exposure is important because it can reduce the risk of secondary malignancies later in life [42–43].

We achieved a satisfactory detection of 94% pulmonary nodules ≥ 5 mm. Yet, we missed the majority of pulmonary nodules < 5mm due to an inability to follow vascular structures on PET/MR images. Surprisingly, the PET-part of the PET/MR detected more [18F]FDG-avid pulmonary nodules than the PET-part of the PET/CT. This may be due to the high detector sensitivity and time-of-flight PET capabilities of our PET/MR scanner and longer PET data acquisition times compared to PET/CT [44–45].

Limitations of our study include the relatively small study population. Cancer in children and adolescents is rare, and therefore patient numbers at single institutional studies are inherently small [8, 14], however our sample mirrors the distribution of malignancies in that population [46–47]. Our study only evaluated patients at baseline. Further studies on the value of PET/MR for treatment monitoring are ongoing.

Previous studies have reported that the T2-signal effect of iron oxides can affect MR-based attenuation correction algorithms [48]. All tumors evaluated in our study showed strong [18F]FDG-metabolism. Treatment monitoring in pediatric tumors is dependent on semi-quantitative scores rather than standardized uptake values [49]. Future studies have to show if the specific iron signal in the bone marrow could be leveraged for improved attenuation correction calculations.

Conclusion

We streamlined PET/MR procedures for “one-stop” cancer staging of pediatric patients in less than one hour. Our ferumoxytol-enhanced PET/MR protocol avoided the administration of gadolinium chelates, lead to 74% reduced effective radiation dose compared to PET/CT and provided equal or superior tumor staging results compared to clinical standard tests in 17 out of 20 patients. The detection of pulmonary nodules with a size of less than 5 mm needs to be improved, yet PET/MR provides comparable detection rates for nodules equal or greater 5 mm and detects [18F]FDG-avid nodules better than PET/CT.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1 Patient and radiologist satisfaction questionnaire (a, b) and results of the radiologist and patient questionnaire before and after intervention (c, d). * indicates significant differences between pre and post intervention.

Supplemental Figure 2: Comparison of three different MR pulse sequences for pulmonary nodule detection. (a) Axial T1-weighted breath-hold LAVA (TR/TE/Flip angle: 4.2/1.7/15) does not show a lung nodule on this section. T2-weighted FSE (TR/TE/Flip angle: 5048/116ms/111) and T2-weighted PROPELLER (TR/TE/Flip angle: 12500/119/110) show a 3 mm nodule in the right upper lobe (white arrow). (b) Number of pulmonary nodules detected on the three sequences.

Supplemental Figure 3 Impairment of pulmonary nodule detection through motion artifacts.

Supplemental Table 1 Patient Characteristics

Supplemental Table 2a Diagnostic value of PET/MR compared to standard imaging tests

Supplemental Table 2b Superior findings of PET/MR versus standard clinical imaging

Supplemental Table 3 In-plane resolution of different MR sequences and CT

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, grant number R01 HD081123-01A1. There is no conflict of interest or industry support for this project. We thank Praveen Gulaka, Dawn Holley and Harsh Gandhi from the PET/MR Metabolic Service Centre for their assistance with the acquisition of PET/MR scans. We thank the members of Daldrup-Link lab for valuable input and discussions regarding this project.

References

- 1.Federman N, Feig SA. PET/CT in evaluating pediatric malignancies: a clinician's perspective. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1920–1922. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.046045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleis M, Daldrup-Link H, Matthay K, et al. Diagnostic value of PET/CT for the staging and restaging of pediatric tumors. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:23–36. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0911-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tatsumi M, Miller JH, Wahl RL. 18F-FDG PET/CT in evaluating non-CNS pediatric malignancies. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1923–1931. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.044628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.London K, Cross S, Onikul E, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT in paediatric lymphoma: comparison with conventional imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:274–284. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1619-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng G, Servaes S, Zhuang H. Value of 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan versus diagnostic contrast computed tomography in initial staging of pediatric patients with lymphoma. Leukemia Lymphoma. 2013;54:737–742. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.727416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.London K, Stege C, Cross S, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT compared to conventional imaging modalities in pediatric primary bone tumors. Pediatr Radiol. 2012;42:418–430. doi: 10.1007/s00247-011-2278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walter F, Czernin J, Hall T, et al. Is there a need for dedicated bone imaging in addition to 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in pediatric sarcoma patients? J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:131–136. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3182282825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponisio MR, McConathy J, Laforest R, Khanna G. Evaluation of diagnostic performance of whole-body simultaneous PET/MRI in pediatric lymphoma. Pediatr Radiol. 2016;46:1258–1268. doi: 10.1007/s00247-016-3601-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miglioretti DL, Johnson E, Williams A, et al. The use of computed tomography in pediatrics and the associated radiation exposure and estimated cancer risk. J Am Med Assoc Pediatr. 2013;167:700–707. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiser DA, Kaste SC, Siegel MJ, Adamson PC. Imaging in childhood cancer: a Society for Pediatric Radiology and Children's Oncology Group Joint Task Force report. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1253–1260. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grueneisen J, Nagarajah J, Buchbender C, et al. Positron Emission Tomography/Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Local Tumor Staging in Patients With Primary Breast Cancer: A Comparison With Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Invest Radiol. 2015;50:505–513. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Souvatzoglou M, Eiber M, Takei T, et al. Comparison of integrated whole-body [11C]choline PET/MR with PET/CT in patients with prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:1486–1499. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2467-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uslu L, Donig J, Link M, et al. Value of 18F-FDG PET and PET/CT for evaluation of pediatric malignancies. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:274–286. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.146290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch FW, Sattler B, Sorge I, et al. PET/MR in children. Initial clinical experience in paediatric oncology using an integrated PET/MR scanner. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43:860–875. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2570-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huellner MW, Appenzeller P, Kuhn FP, et al. Whole-body nonenhanced PET/MR versus PET/CT in the staging and restaging of cancers: preliminary observations. Radiology. 2014;273:859–869. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Kallmes DF, et al. Intracranial Gadolinium Deposition after Contrast-enhanced MR Imaging. Radiology. 2015;275:772–782. doi: 10.1148/radiol.15150025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang W, Tao X, Fang F, Zhang S, Xu C. Benign and malignant ovarian steroid cell tumors, not otherwise specified: case studies, comparison, and review of the literature. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:53. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-6-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schafer JF, Gatidis S, Schmidt H, et al. Simultaneous whole-body PET/MR imaging in comparison to PET/CT in pediatric oncology: initial results. Radiology. 2014;273:220–231. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gatidis S, Schmidt H, Gucke B, et al. Comprehensive Oncologic Imaging in Infants and Preschool Children With Substantially Reduced Radiation Exposure Using Combined Simultaneous (1)(8)F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Direct Comparison to (1)(8)F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography. Invest Radiol. 2016;51:7–14. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sher AC, Seghers V, Paldino MJ, et al. Assessment of Sequential PET/MRI in Comparison With PET/CT of Pediatric Lymphoma: A Prospective Study. Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206:623–631. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.15083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricard F, Cimarelli S, Deshayes E, et al. Additional Benefit of F-18 FDG PET/CT in the staging and follow-up of pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:672–677. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318217ae2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kneisl JS, Patt JC, Johnson JC, Zuger JH. Is PET useful in detecting occult nonpulmonary metastases in pediatric bone sarcomas? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;450:101–104. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000229329.06406.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klenk C, Gawande R, Uslu L, et al. Ionising radiation-free whole-body MRI versus 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT scans for children and young adults with cancer: a prospective, non-randomised, single-centre study. The Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:275–285. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70021-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattsson S, Johansson L, Leide Svegborn S, et al. Radiation Dose to Patients from Radiopharmaceuticals: a Compendium of Current Information Related to Frequently Used Substances. Annals ICRP. 2015;44:7–321. doi: 10.1177/0146645314558019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deak PD, Smal Y, Kalender WA. Multisection CT protocols: sex- and age-specific conversion factors used to determine effective dose from dose-length product. Radiology. 2010;257:158–166. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cipriano C, Brockman L, Romancik J, et al. The Clinical Significance of Initial Pulmonary Micronodules in Young Sarcoma Patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015;37:548–553. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciet P, Tiddens HA, Wielopolski PA, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in children: common problems and possible solutions for lung and airways imaging. Pediatr Radiol. 2015;45:1901–1915. doi: 10.1007/s00247-015-3420-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Schulthess GK, Veit-Haibach P. Workflow Considerations in PET/MR Imaging. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:19S–24S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.129239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez-Moller A, Eiber M, Nekolla SG, et al. Workflow and scan protocol considerations for integrated whole-body PET/MRI in oncology. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1415–1426. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.109348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanderby SA, Babyn PS, Carter MW, Jewell SM, McKeever PD. Effect of anesthesia and sedation on pediatric MR imaging patient flow. Radiology. 2010;256:229–237. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aghighi M, Pisani LJ, Sun Z, et al. Speeding up PET/MR for cancer staging of children and young adults. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:4239–4248. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4332-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eiber M, Martinez-Moller A, Souvatzoglou M, et al. Value of a Dixon-based MR/PET attenuation correction sequence for the localization and evaluation of PET-positive lesions. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1691–1701. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1842-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klenk C, Gawande R, Tran VT, et al. Progressing Toward a Cohesive Pediatric 18F-FDG PET/MR Protocol: Is Administration of Gadolinium Chelates Necessary? J Nucl Med. 2016;57:70–77. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.161646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daldrup-Link HE, Rummeny EJ, Ihssen B, et al. Iron-oxide-enhanced MR imaging of bone marrow in patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: differentiation between tumor infiltration and hypercellular bone marrow. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:1557–1566. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1270-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li YW, Chen ZG, Wang JC, Zhang ZM. Superparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for focal hepatic lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4334–4344. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferrucci JT, Stark DD. Iron oxide-enhanced MR imaging of the liver and spleen: review of the first 5 years. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155:943–950. doi: 10.2214/ajr.155.5.2120963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perazella MA. Current status of gadolinium toxicity in patients with kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:461–469. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06011108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varallyay CG, Nesbit E, Fu R, et al. High-resolution steady-state cerebral blood volume maps in patients with central nervous system neoplasms using ferumoxytol, a superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:780–786. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu M, Cohen MH, Rieves D, Pazdur R. FDA report: Ferumoxytol for intravenous iron therapy in adult patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:315–319. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muehe AM, Feng D, von Eyben R, et al. Safety Report of Ferumoxytol for Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Children and Young Adults. Invest Radiol. 2016;51:221–227. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fakhran S, Alhilali L, Kale H, Kanal E. Assessment of rates of acute adverse reactions to gadobenate dimeglumine: review of more than 130,000 administrations in 7.5 years. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:703–706. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearce MS, Salotti JA, Little MP, et al. Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:499–505. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60815-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brenner DJ, Doll R, Goodhead DT, et al. Cancer risks attributable to low doses of ionizing radiation: assessing what we really know. Proc Nat Acad Scie (USA) 2003;100:13761–13766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235592100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Minamimoto R, Levin C, Jamali M, et al. Improvements in PET Image Quality in Time of Flight (TOF) Simultaneous PET/MRI. Mol Imaging Biol. 2016;18:776–781. doi: 10.1007/s11307-016-0939-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grant AM, Deller TW, Khalighi MM, Maramraju SH, Delso G, Levin CS. NEMA NU 2–2012 performance studies for the SiPM-based ToF-PET component of the GE SIGNA PET/MR system. Med Phys. 2016;43:2334. doi: 10.1118/1.4945416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:83–103. doi: 10.3322/caac.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borra RJ, Cho HS, Bowen SL, et al. Effects of ferumoxytol on quantitative PET measurements in simultaneous PET/MR whole-body imaging: a pilot study in a baboon model. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging physics. 2015;2:6. doi: 10.1186/s40658-015-0109-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meignan M, Gallamini A, Meignan M, et al. Report on the First International Workshop on Interim-PET-Scan in Lymphoma. Leuk Lymph. 2009;50:1257–1260. doi: 10.1080/10428190903040048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1 Patient and radiologist satisfaction questionnaire (a, b) and results of the radiologist and patient questionnaire before and after intervention (c, d). * indicates significant differences between pre and post intervention.

Supplemental Figure 2: Comparison of three different MR pulse sequences for pulmonary nodule detection. (a) Axial T1-weighted breath-hold LAVA (TR/TE/Flip angle: 4.2/1.7/15) does not show a lung nodule on this section. T2-weighted FSE (TR/TE/Flip angle: 5048/116ms/111) and T2-weighted PROPELLER (TR/TE/Flip angle: 12500/119/110) show a 3 mm nodule in the right upper lobe (white arrow). (b) Number of pulmonary nodules detected on the three sequences.

Supplemental Figure 3 Impairment of pulmonary nodule detection through motion artifacts.

Supplemental Table 1 Patient Characteristics

Supplemental Table 2a Diagnostic value of PET/MR compared to standard imaging tests

Supplemental Table 2b Superior findings of PET/MR versus standard clinical imaging

Supplemental Table 3 In-plane resolution of different MR sequences and CT