Abstract

Background

Pyruvate kinase isozymes M2 (PKM2), as a member of pyruvate kinase family, plays a role of glycolytic enzyme in glucose metabolism. It also functions as protein kinase in cell proliferation, signaling, immunity, and gene transcription. In this study, the role of PKM2 in neuropathic pain induced by chronic constriction injury (CCI) was investigated.

Methods

Rats were randomly grouped to establish CCI models. PKM2, extracellular regulated protein kinases (EKR), p-ERK, signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT3), p-STAT3, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) and p-PI3K/AKT proteins expression in spinal cord was examined by Western blot analysis. Cellular location of PKM2 was examined by immunofluorescence. Knockdown of PKM2 was achieved by intrathecal injection of specific small interfering RNA (siRNA). Von Frey filaments and radiant heat tests were performed to determine mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia respectively. Lactate and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) contents were measured by specific kits. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) levels were detected by ELISA kits.

Results

CCI markedly increased PKM2 level in rat spinal cord. Double immunofluorescent staining showed that PKM2 co-localized with neuron, astrocyte, and microglia. Intrathecal injection of PKM2 siRNA not only attenuated CCI-induced ERK and STAT3 activation, but also attenuated mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia induced by CCI. However, PKM2 siRNA failed to inhibit the activation of AKT. In addition, PKM2 siRNA significantly suppressed the production of lactate and pro-inflammatory mediators.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that inhibiting PKM2 expression effectively attenuates CCI-induced neuropathic pain and inflammatory responses in rats, possibly through regulating ERK and STAT3 signaling pathway.

Keywords: PKM2, Neuropathic pain, Chronic constriction injury, Lactate, p-ERK, p-STAT

Background

Neuropathic pain, which is caused by heterogeneous etiology, remains a Gordian knot for pain management practitioners [1]. Despite numerous investigations focused on nociceptors, modulators and downstream signaling pathways in the past few decades [2, 3], we still can’t elucidate the underlying mechanisms of neuropathic pain very well.

According to the agreed definition, issued by the International Association for the Study of Pain, neuropathic pain is caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system. The lesion or dysfunction results in the localized release of neurotransmitters, neurotrophic factors, cytokines and chemokines. These substances increase the sensitivity and excitability of primary sensory neurons by lowering the activation threshold of peripheral nociceptors, which results in peripheral sensitization [4, 5]. Increased outputs from primary afferent terminals triggers synaptic plasticity and long lasting transcriptional and post-translational changes in central nervous system, which is defined as central sensitization [6, 7]. Peripheral and central sensitization are considered important mechanism in neuropathic pain and contribute to hypersensitive pain behaviors [7]. Inflammatory process and metabolic dysregulation are two sides of the same coin in central sensitization [8, 9]. After peripheral nerve injury, glial cells are initially activated and subsequently generate numerous pro-inflammatory mediators, contributing to the development of neuropathic pain [10, 11]. The pro-inflammatory phenotype of glial cells request enhanced energy supply [12, 13], displaying a glycolytic metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis [14]. The enhanced glycolysis in cells provides biosynthetic precursors for pro-inflammatory proteins [15].

Glucose metabolism is precisely regulated by a number of glycolytic enzymes, including hexokinases, pyruvate kinase, and pyruvate dehydrogenase. Pyruvate kinase is a rate limiting enzyme catalyzing the final step of glycolysis, converting phosphoenolpyruvic acid and ADP to pyruvate and ATP [16]. PKM2 is one of the four pyruvate kinase isoforms, and mainly expresses in normal proliferating cells and cancer cells [16]. Under catalysis of PKM2, glucose entering glycolytic pathway is metabolized to lactate and ATP rather than oxidized in mitochondria [17]. ATP, ligand of P2X family receptor, is an important pain mediator [18]. Lactate is an energy substrate for neurons [19] and has been identified as an important signaling molecule in neuro-immune, neuronal plasticity, neuron-glia interactions, as well as nociception [9, 20–22]. Lactate can also furtherly promote glial cells to release the pro-inflammatory cytokines under pathological conditions [23]. With the deepening of research, PKM2 is found to be a generalist, which can also function as a protein kinase by nuclear translocation under pathological stimulation [24]. PKM2 can phosphorylates ERK1/2, STAT-3 and PI3K/AKT, enhancing cell proliferation and subsequent related gene transcription [25–27]. These signaling pathways are activated in spinal cord (SC) after nerve injury and contribute to the development of neuropathic pain [28–30]. PKM2 also interacts with hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha(HIF-1α) and upregulates the expression of IL-1β [31] in LPS-activated macrophages. Although PKM2 plays an important role in metabolism, gene transcription and inflammation, whether or not it participates in the process of neuropathic pain remains unknown.

In this study, we developed a clinically relevant model of neuropathic pain induced by CCI and investigated the potential role of PKM2 in neuropathic pain. We were confirmed that CCI induced significant upregulation of PKM2 in SC. We also demonstrated that inhibiting PKM2 by intrathecal injection of specific siRNA effectively attenuated CCI-induced rat neuropathic pain and inflammatory responses, possibly through regulating ERK and STAT3 signaling pathway. This research may represent a novel strategy for treating neuropathic pain.

Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighed 200–240 g were obtained from Experimental Animal Center, Nantong University. Rats were housed on a 12:12 light-dark cycle at 22 ± 1 °C with free access to food and water. The experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nantong University and were conducted in accordance with guidelines of the International Association for the Study of Pain.

Establishment of the neuropathic pain model

CCI model of sciatic nerve injury was established according to procedures described by Ding Y et al. [32]. In brief, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, and the left sciatic nerve was loosely ligated by 4-0 chromic gut sutures at four segments with 1 mm apart. The sutures were gently tightened until a brisk twitch of the left hind limb was observed. The same surgical procedure was performed in the sham groups except ligating the sciatic nerve.

Behavioral testing

Mechanical allodynia was measured by von Frey filaments. Rats were placed into a transparent plexiglas compartments upon a metal mesh. The plantar surface of left paw was perpendicularly subjected to a series of von Frey hairs with logarithmically incrementing stiffness (0.4-26 g) until the filaments bowed slightly. Rapid paw withdrawal or flinching were considered positive responses. The 50% paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) was determined using Dixon’s up-down method [33]. Thermal hyperalgesia was tested by radiant heat using Hargreaves apparatus (IITC Life Science Inc., Woodland Hills, CA) and represented as paw-withdrawal latency (PWL). The rats were placed in hyaline plastic compartments and the plantar surface of the left hind paw was exposed to a radiant heat source through the glass plate. Mean PWL was averaged from latency of three successive tests. A cut-off time of 20s was set to prevent tissue damage.

PKM-2 siRNA and lumbar intrathecal injection

The siRNA was commercially synthesized (Genepharma, Shanghai, China). siRNA duplexes that specifically targeted PKM2 were: sense 5’-CAUCUACCACUUGCAAUUATT-3′ and anti-sense 5′- UAAUUGCAAGUGGUAGAUGTT-3′. Non-targeting siRNA (NT-siRNA) was synthesized by a scrambled sequence of nucleotides as a control siRNA. Before intrathecal injection, siRNA was dissolved by RNase-free water to a concentration of 0.75μg/μl and then mixed with polyethyleneimine (PEI, dissolved in 5% glucose, 1 μg of siRNA was mixed with 0.18 μl of PEI) for 10 min. Intrathecal injection was performed with a micro syringe between L5 and L6 intervertebral spaces to deliver the reagents (20 μl) into the cerebral spinal fluid [34]. Once the needle inserted subarachnoid space successfully, a brisk tail flick could be observed.

Western blot analysis

Lumbar SC (L4–L5) were excised rapidly from deeply anesthetized rats. Total proteins were extracted by protein extraction kits, separated by 8% SDS–PAGE and then transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The membranes were blocked with 5% milk and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody against PKM-2 (anti-mouse, 1:500, Santa Cruz, USA), Stat3 (anti-mouse, 1:500, Santa Cruz, USA), p-Stat3 (anti-mouse, 1:500, Santa Cruz, USA), ERK (anti-mouse, 1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, American), p-ERK (anti-mouse, 1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, American), AKT (anti-mouse, 1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, American), p-AKT (anti-mouse, 1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, American) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (anti-mouse, 1:1000, Santa Cruz, USA). After washed with PBST containing 20% Tween-20, the membranes were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:5000, Southern Biotech, USA). Immunoblots were visualized and quantified using an enhanced chemiluminescence system. Relative protein levels were normalized to GAPDH, which was used as a loading control for total protein.

Measurement of lactate and ATP

The Lumbar SC (L4–L5) were excised rapidly from deeply anesthetized rats, and then the tissues were homogenized into 500 μl lactate assay buffer (Lactate Colorimetric kit, Abcam) and centrifuged at 10,000×g for 4 min. Samples were tested according to the manufacturer’s protocol and lactate levels were normalized to control samples. ATP levels were measured using a ATP assay kit (Beyotime, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All operations were performed on ice to precisely determine the ATP concentration.

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Protein samples were prepared in the same way as Western blot. Levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in each group were detected by ELISA kits (Jiancheng Biotech, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistochemistry

Under deep anesthesia with pentobarbital sodium, rats were transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The L4-L5 SC were dissected out and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C. After consecutively dehydrated in 20% and 30% sucrose, SC sections were crosscut into 8 um thick in a cryostat and blocked with 10% donkey serum, 3% bovine serum albumin and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 2 h at room temperature. Then, the sections were incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C: PKM-2(anti-mouse, 1:50, Santa Cruz, USA), neuronal nuclei (NeuN) (anti-rabbit, 1:300, Cell Signaling Technology, American), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (anti-rabbit, 1:200; Sigma, USA) and ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba1) (anti-rabbit, 1:500, Wako, Japan). The sections were incubated with FITC-conjugated Donkey or CY3-conjugated Donkey secondary antibodies or a mixture of both for double staining. After washed three times in PBS, the sections were examined with a Leica fluorescence microscope.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 software and results were expressed as means ± SEM. Image J was used to process the density of specific bands and fluorescence intensity. Behavioral date was analyzed by a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni test as the multiple comparison analysis. Differences between two groups were analyzed with Student t test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

CCI produced neuropathic pain accompanied by the upregulation of PKM2 in SC

As is shown in Fig. 1a, b, there were no statistical differences in PWT or PWL between groups 1 day before surgery (p > 0.05). In CCI group, PWT and PWL decreased at day 1 after CCI and then gradually reduced to the minimum at day 7 and maintained at a low level until day 21 compared with sham group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1a, b). These behavioral changes suggested that CCI produced a progressive development of neuropathic pain. Western blot analysis showed that CCI rapidly and persistently increased PKM2 expression in SC compared with naïve rats (P < 0.05), starting at day 3, peaking at day 7 and maintaining until day 21 (Fig. 1c, d). However, sham surgery had no significant effect on PKM2 expression in SC at day 7 as compared to naïve rats (p > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Changes of mechanical allodynia, heat hyperalgesia and PKM2 expression in rats after CCI. a, b CCI induced a significant decrease in PWT (a) and PWL (b). *P < 0.05 versus sham group. Five rats per group. c, d Western blot was performed to detect PKM2 expression in spinal cord. Each group comprised four corresponding spinal cord segments. Representative PKM2 protein bands were exhibited on the left (c), and statistical analysis histogram was shown on the right (d). *P < 0.05 versus sham group

CCI enhanced PKM2 expression in neurons and glia cells

We then invested the expression and cellular distribution of PKM2 in SC dorsal horn after CCI by immunofluorescence staining. As is shown in Fig. 2a, PKM2 presented low basal expression level in ipsilateral SC dorsal horn in naïve animals. However, a marked increase of PKM2 immunoreactivity at day 7 and day 10 could be observed in CCI rats (Fig. 2a). We performed double staining of PKM2 with three major spinal nerve cell-specific markers at day 7: NeuN (for neurons), GFAP (for astrocytes) and Iba-1(for microglia). As is shown in Fig. 2b, PKM2 co-localized with NeuN, GFAP and Iba-1. These results suggested that PKM2 widely expressed in neurons, astrocytes and microglia cells after CCI.

Fig. 2.

Expression and distribution of PKM2 in spinal cord dorsal horn after CCI. A Immunofluorescence showed that expression of PKM2 (red) was increased at day 7 and day 10. B Double staining showed that PKM2 co-localized with neuron marker NeuN (a-d), microglia marker Iba-1 (e-h), and astrocyte marker GFAP (i-l)

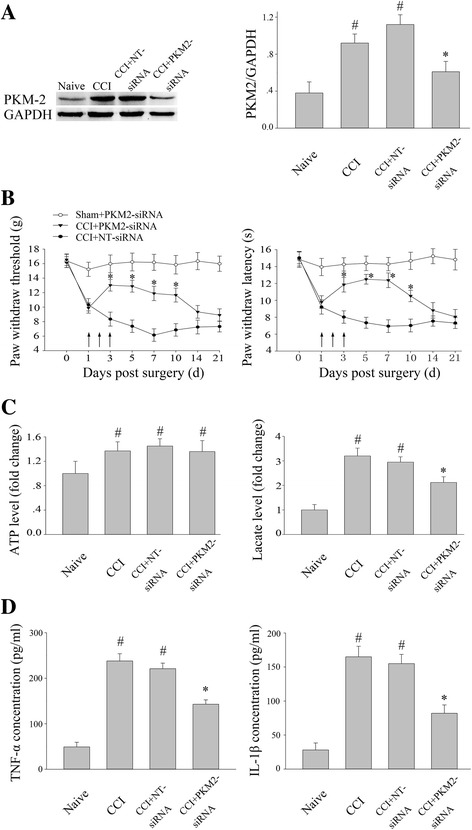

PKM2 siRNA attenuated not only pain hypersensitivity but also the production of lactate, TNF-α and IL-1β in SC after CCI

To investigate the function of PKM2 in neuropathic pain, we performed intrathecal injection of 15 μl PKM2 siRNA or NT siRNA (0.75 μg/μl) for three continuous days (day 1, 2, 3) after CCI. Western blot analysis was used to confirm the knock-down efficiency at day 3, 6 h after the last injection. As is shown in Fig. 3a, PKM2 siRNA (P < 0.05) significantly decreased PKM2 expression, while NT-SiRNA didn’t. PKM2 siRNA partially restrained the downtrend of PWT and PWL for approximately 7 days in CCI rats (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3b). However, PKM2 siRNA did not affect normal pain sensation in sham group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3b). CCI induced significant increase in ATP and lactate level in L4-5 SC (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3c). The increased lactate level was inhibited by PKM2 siRNA (P < 0.05), while the ATP level was not influenced (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3c). Besides, in view of the important role of PKM-2 in the process of inflammation, we performed ELISA to exam the change of inflammatory factors in SC. CCI induced notable increase in TNF-α and IL-1β in SC (P < 0.05), and the increase was significantly inhibited by PKM-2 siRNA (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Intrathecal PKM2 siRNA treatment attenuated pain hypersensitivity and the production of lactate and pro-inflammatory transmitter induced by CCI. a The expression of PKM2 following intrathecal injection of siRNAs after CCI; PKM2 siRNA and NT siRNA (daily for 3 consecutive days, 15 μl each time, 0.75 μg/μl) were intrathecally injected. Tissues were harvested at day 3, 6 h after the last injection. *P < 0.05 versus NT siRNA group, #P < 0.05 versus naïve group. Four rats per group. b Intrathecal injection of PKM2 siRNA for three consecutive days (day 1, 2, 3) increased paw withdraw threshold and latency for almost 7 days (day 3 to day 10). c PKM2 siRNA significantly attenuated lactate production, while ATP production were not influenced. d Meanwhile, both TNF-α and IL-1β production were also inhibited by PKM2 siRNA. *P < 0.05 versus NT siRNA group. #P < 0.05 versus naïve group. Four rats per group

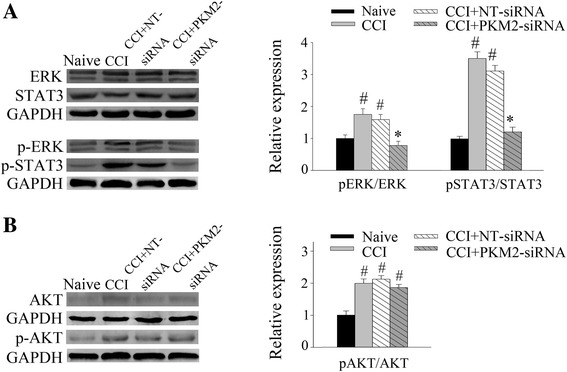

Reducing PKM2 expression inhibited the activation of STAT3 and ERK signaling induced by CCI

In an effort to clarify the potential mechanism of PKM2 in the process of neuropathic pain, we examined the phosphorylation level of several classic signaling pathways in neuropathic pain model after treatment with PKM2 siRNA. Increased PKM2 in CCI group was coincided with elevated pSTAT3/STAT3 (P < 0.05), pERK/ERK (P < 0.05) and pAKT/AKT (P < 0.05) expression (Fig. 4a, b). PKM2 siRNA treatment significantly reduced the pSTAT3/STAT3 (P < 0.05) and pERK/ERK (P < 0.05) ratios (Fig. 4a). However, the pAKT/AKT ratio was not influenced by PKM2 siRNA (p > 0.05) (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

PKM2 siRNA reversed the phosphorylation of ERK and STAT3 in the spinal cord L4–5 segments induced by CCI. Western blot was performed to evaluate the levels of phosphorylated ERK, STAT3, and AKT in protein extracted from the L4–5 segment of spinal cord in each group. GAPDH was used as an internal control. a Treatment with PKM2 siRNA significantly reduced the pERK/ERK and pSTAT3/STAT3 ratios. *P < 0.05 versus NT siRNA group. #P < 0.05 versus naïve group. Four rats per group. b PKM2 siRNA failed to inhibit the phosphorylation of AKT. #P < 0.05 versus naïve group. Four rats per group

Discussion

In present study, we investigated the analgesic effect of intrathecal injection of PKM2 siRNA in a neuropathic pain animal model induced by sciatic nerve ligation. An appropriate animal model is important for the preclinical study of pain. We established CCI model by ligating sciatic nerve as described by Ding Y [32] for mirroring features of clinical neuropathic pain. The progressive mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia, which were characterized by the reduction of PWT and PWL, indicated that we successfully established the neuropathic pain model.

After peripheral nerve injury, glial cells were activated immediately and secreted massive inflammatory and neurotransmitter mediators, which sensitized neuron and furtherly aggravated central sensitization [35, 36]. Sensitized neuron and activated glial cells underwent metabolic changes to meet the enhanced energy demand and to respond to the disorders of nervous system better [13, 37]. The alterations of metabolism promoted pro-inflammatory phenotype conversion, transcription regulation, as well as posttranscriptional events in these immune cells [38]. In previous studies, CCI produced significant increases in glucose utilization and metabolic rate in spinal dorsal horns [39, 40]. Decades of researches have shown that PKM2 seems to be an important linker between metabolism and inflammation [38, 41]. In a proteomics study, Komori et al. found that PKM2 was significantly upregulated in dorsal root ganglions in a ligation spinal nerve induced-neuropathic pain model [42]. Hence, whether PKM2 participates in neuropathic pain has caught our most attention. In our study, we found that PKM2 quickly increased in SC after CCI, accompanied by behavioral changes. It indicates that PKM2 may participate in the process of neuropathic pain. To prove our speculation, we performed intrathecal injection of PKM2 siRNA in rats. Our results showed that siRNA not only suppressed the PKM2 protein expression, but also obviously alleviated CCI induced pain hypersensitivity. These data suggested that PKM2 plays a critical role in the development of neuropathic pain.

To explore the detailed mechanisms by which PKM2 contributed to neuropathic pain, we then investigated the downstream events of PKM2. PKM2 exists in two forms-- enzymatic active tetramer and protein kinase active dimeric. The tetramer form drives glucose towards oxidative metabolism via the tricarboxylic acid cycle, accompanied by the generation of large amounts of ATP [43]. Although the dimers form of PKM2 does not exert metabolic enzyme activity, it can regulate cell metabolism via its non-metabolic functions [44]. When epidermal growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor are activated, the dimeric PKM2 translocates into the nucleus and interacts with hypoxia inducible factor-1 and β-catenin to promote the expression of target genes, including GLUT1, SLC2A1, LDHA and PDK1. Upregulation of these glycolysis genes enhances glucose consumption and lactate production [44, 45]. ATP and lactate are important energy substance [19] involved in central sensitization and mediate allodynia in multiple pain models [20, 21]. In our study, we observed increases in ATP and lactate in SC. Interestingly, lactate significantly decreased after intrathecal injection of PKM2 siRNA, while the ATP concentration was not obviously affected.

In addition to the well-known role in glucose metabolism, PKM2 can also translocate into the nucleus in a dimeric form and function as protein kinase to regulate gene transcription under certain pathophysiological conditions. Nuclear PKM2 can phosphorylate the transcription factor STAT3, ERK1/2 and PI3K/ATK signaling pathway to promote cell proliferation and invasion [24, 26, 27]. Additionally, PKM2 increased strongly in LPS-activated macrophages, translocated into the nucleus and bounded with HIF-1α and STAT3 to promote the expression of inflammatory cytokines Il-1β and TNF-α [31, 46]. Inhibiting these signaling pathways can effectively suppress the generation of pro-inflammatory and neuropathic pain [28–30]. Accordingly, we examined the phosphorylation of these signaling pathways after intrathecal injection of PKM2 siRNA. PKM2 siRNA inhibited the phosphorylation of STAT3 and ERK signaling, but did not influence AKT signaling. Furthermore, IL-1β and TNF-α were down-regulated in SC. These results indicated that PKM2 contributes to neuropathic pain and inflammatory responses, possibly through regulating ERK and STAT3 signaling pathway as a protein kinase.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that oxidative stress plays an important role in central sensitization [47]. Reducing oxidative stress level by inhibiting nuclear factor E2-related factor 2, a critical endogenous protective factor in antioxidant defense, can effectively alleviate neuropathic pain [48]. Under stimuli of oxidative stress, PKM2 translocates into nucleus to function as a protein kinase [49]. So, weather PKM2 is involved in oxidative stress during the process of neuropathic pain needs further study in future.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that CCI induced significant increase of PKM2 in SC. RNAi-mediated down-regulation of PKM2 effectively attenuated CCI-induced rat neuropathic pain and inflammatory responses, possibly through regulating ERK and STAT3 signaling pathway. Therefore, reducing PKM2 levels in SC using siRNA might be an effective therapeutic approach for relieving neuropathic pain.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81401365); a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD); Nantong science and technology project (MS12015056).

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are within the paper.

Abbreviations

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- CCI

Chronic constriction injury

- ELISA

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- ERK

Extracellular regulated protein kinases

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HIF-1α

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha

- Iba-1

Ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1 beta

- NeuN

Neuronal nuclei

- NT-siRNA

Non-targeting siRNA

- PKM2

Pyruvate kinase isozymes M2

- PL3K/AKT

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase inhibitor

- PWL

Paw-withdrawal latency

- PWT

Paw withdrawal threshold

- SC

Spinal cord

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

- STAT3

Signal transducers and activators of transcription 3

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

Authors’ contributions

BBW, SYL, ZLX and XJL conceived and designed the experiments. BBW, BBF, XGX, YLC and RXL performed the experiments. BBW, ZLX, XJL analyzed the data. BBW, SYL contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nantong University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhongling Xu, Email: jsrdwbb1@sohu.com.

Xiaojuan Liu, Email: lxj@ntu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, McNicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, Gilron I, Haanpaa M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, Kamerman PR, Lund K, Moore A, Raja SN, Rice AS, Rowbotham M, Sena E, Siddall P, Smith BH, Wallace M. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:162–173. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70251-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiguchi N, Kobayashi Y, Kishioka S. Chemokines and cytokines in neuroinflammation leading to neuropathic pain. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2012;12:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uceyler N, Sommer C. Cytokine regulation in animal models of neuropathic pain and in human diseases. Neurosci Lett. 2008;437:194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silva RL, Lopes AH, Guimaraes RM, Cunha TM. CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling in pathological pain: role in peripheral and central sensitization. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;105:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyengar S, Ossipov MH, Johnson KW. The role of calcitonin gene-related peptide in peripheral and central pain mechanisms including migraine. Pain. 2017;158:543–559. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark AK, Malcangio M. Fractalkine/CX3CR1 signaling during neuropathic pain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:121. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao YJ, Ji RR. Chemokines, neuronal-glial interactions, and central processing of neuropathic pain. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;126:56–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stemkowski PL, Smith PA. Sensory neurons, ion channels, inflammation and the onset of neuropathic pain. Can J Neurol Sci. 2012;39:416–435. doi: 10.1017/S0317167100013937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahman MH, Jha MK, Kim JH, Nam Y, Lee MG, Go Y, Harris RA, Park DH, Kook H, Lee IK, Suk K. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-mediated glycolytic metabolic shift in the dorsal root ganglion drives painful diabetic neuropathy. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:6011–6025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.699215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narita M, Yoshida T, Nakajima M, Narita M, Miyatake M, Takagi T, Yajima Y, Suzuki T. Direct evidence for spinal cord microglia in the development of a neuropathic pain-like state in mice. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1337–1348. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao B, Pan Y, Xu H, Song X. Hyperbaric oxygen attenuates neuropathic pain and reverses inflammatory signaling likely via the Kindlin-1/Wnt-10a signaling pathway in the chronic pain injury model in rats. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:1. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0713-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Q, Bian G, Chen P, Liu L, Yu C, Liu F, Xue Q, Chung SK, Song B, Ju G, Wang J. Aldose reductase regulates microglia/macrophages polarization through the cAMP response element-binding protein after spinal cord injury in mice. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:662–676. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-9035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jha MK, Lee WH, Suk K. Functional polarization of neuroglia: implications in neuroinflammation and neurological disorders. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;103:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orihuela R, McPherson CA, Harry GJ. Microglial M1/M2 polarization and metabolic states. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:649–665. doi: 10.1111/bph.13139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang L, Xie M, Yang M, Yu Y, Zhu S, Hou W, Kang R, Lotze MT, Billiar TR, Wang H, Cao L, Tang D. PKM2 regulates the Warburg effect and promotes HMGB1 release in sepsis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4436. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang W, Lu Z. Pyruvate kinase M2 at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2015;128:1655–1660. doi: 10.1242/jcs.166629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Chen K, Sloan SA, Bennett ML, Scholze AR, O'Keeffe S, Phatnani HP, Guarnieri P, Caneda C, Ruderisch N, Deng S, Liddelow SA, Zhang C, Daneman R, Maniatis T, Barres BA, Wu JQ. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2014;34:11929–11947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton SG, McMahon SB. ATP as a peripheral mediator of pain. J Auton Nerv Syst. 2000;81:187–194. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1838(00)00137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schurr A, Payne RS, Miller JJ, Rigor BM. Brain lactate is an obligatory aerobic energy substrate for functional recovery after hypoxia: further in vitro validation. J Neurochem. 1997;69:423–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69010423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jha MK, Song GJ, Lee MG, Jeoung NH, Go Y, Harris RA, Park DH, Kook H, Lee IK, Suk K. Metabolic connection of inflammatory pain: pivotal role of a pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-pyruvate dehydrogenase-lactic acid axis. J Neurosci. 2015;35:14353–14369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1910-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang J, Ruchti E, Petit JM, Jourdain P, Grenningloh G, Allaman I, Magistretti PJ. Lactate promotes plasticity gene expression by potentiating NMDA signaling in neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:12228–12233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322912111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang F, Lane S, Korsak A, Paton JF, Gourine AV, Kasparov S, Teschemacher AG. Lactate-mediated glia-neuronal signalling in the mammalian brain. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3284. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersson AK, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Lactate induces tumour necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6 and interleukin-1beta release in microglial- and astroglial-enriched primary cultures. J Neurochem. 2005;93:1327–1333. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao X, Wang H, Yang JJ, Liu X, Liu ZR. Pyruvate kinase M2 regulates gene transcription by acting as a protein kinase. Mol Cell. 2012;45:598–609. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao X, Wang H, Yang JJ, Chen J, Jie J, Li L, Zhang Y, Liu ZR. Reciprocal regulation of protein kinase and pyruvate kinase activities of pyruvate kinase M2 by growth signals. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:15971–15979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.448753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller KE, Doctor ZM, Dwyer ZW, Lee YS. SAICAR induces protein kinase activity of PKM2 that is necessary for sustained proliferative signaling of cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2014;53:700–709. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang C, Jiang J, Ji J, Cai Q, Chen X, Yu Y, Zhu Z, Zhang J. PKM2 promotes cell migration and inhibits autophagy by mediating PI3K/AKT activation and contributes to the malignant development of gastric cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7:2886. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03031-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen NF, Chen WF, Sung CS, Lu CH, Chen CL, Hung HC, Feng CW, Chen CH, Tsui KH, Kuo HM, Wang HM, Wen ZH, Huang SY. Contributions of p38 and ERK to the antinociceptive effects of TGF-beta1 in chronic constriction injury-induced neuropathic rats. J Headache Pain. 2016;17:72. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0665-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuda M, Kohro Y, Yano T, Tsujikawa T, Kitano J, Tozaki-Saitoh H, Koyanagi S, Ohdo S, Ji RR, Salter MW, Inoue K. JAK-STAT3 pathway regulates spinal astrocyte proliferation and neuropathic pain maintenance in rats. Brain. 2011;134:1127–1139. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo JR, Wang H, Jin XJ, Jia DL, Zhou X, Tao Q. Effect and mechanism of inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signal pathway on chronic neuropathic pain and spinal microglia in a rat model of chronic constriction injury. Oncotarget. 2017;8:52923. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palsson-McDermott EM, Curtis AM, Goel G, Lauterbach MA, Sheedy FJ, Gleeson LE, van den Bosch MW, Quinn SR, Domingo-Fernandez R, Johnston DG, Jiang JK, Israelsen WJ, Keane J, Thomas C, Clish C, Vander Heiden M, Xavier RJ, O'Neill LA. Pyruvate kinase M2 regulates Hif-1alpha activity and IL-1beta induction and is a critical determinant of the warburg effect in LPS-activated macrophages. Cell Metab. 2015;21:65–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding Y, Yao P, Hong T, Han Z, Zhao B, Chen W. The NO-cGMP-PKG signal transduction pathway is involved in the analgesic effect of early hyperbaric oxygen treatment of neuropathic pain. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:51. doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0760-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hylden JL, Wilcox GL. Intrathecal morphine in mice: a new technique. Eur J Pharmacol. 1980;67:313–316. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raghavendra V, Tanga FY, DeLeo JA. Complete Freunds adjuvant-induced peripheral inflammation evokes glial activation and proinflammatory cytokine expression in the CNS. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:467–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vallejo R, Tilley DM, Vogel L, Benyamin R. The role of glia and the immune system in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain. Pain Pract. 2010;10:167–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rahman MH, Jha MK, Suk K. Evolving insights into the pathophysiology of diabetic neuropathy: implications of malfunctioning glia and discovery of novel therapeutic targets. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22:738–757. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666151204001234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alves-Filho JC, EM P-MD. Pyruvate kinase M2: a potential target for regulating inflammation. Front Immunol. 2016;7:145. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mao J, Hayes RL, Price DD, Coghill RC, Lu J, Mayer DJ. Post-injury treatment with GM1 ganglioside reduces nociceptive behaviors and spinal cord metabolic activity in rats with experimental peripheral mononeuropathy. Brain Res. 1992;584:18–27. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90873-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mao J, Price DD, Coghill RC, Mayer DJ, Hayes RL. Spatial patterns of spinal cord [14C]-2-deoxyglucose metabolic activity in a rat model of painful peripheral mononeuropathy. Pain. 1992;50:89–100. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90116-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Harris MH, Ramanathan A, Gerszten RE, Wei R, Fleming MD, Schreiber SL, Cantley LC. The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature. 2008;452:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature06734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komori N, Takemori N, Kim HK, Singh A, Hwang SH, Foreman RD, Chung K, Chung JM, Matsumoto H. Proteomics study of neuropathic and nonneuropathic dorsal root ganglia: altered protein regulation following segmental spinal nerve ligation injury. Physiol Genomics. 2007;29:215–230. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00255.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong N, De Melo J, Tang D. PKM2, a central point of regulation in cancer metabolism. Int J Cell Biol. 2013;2013:242513. doi: 10.1155/2013/242513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo W, Semenza GL. Pyruvate kinase M2 regulates glucose metabolism by functioning as a coactivator for hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2011;2:551–556. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang W, Xia Y, Ji H, Zheng Y, Liang J, Huang W, Gao X, Aldape K, Lu Z. Nuclear PKM2 regulates beta-catenin transactivation upon EGFR activation. Nature. 2011;480:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature10598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang P, Li Z, Li H, Lu Y, Wu H, Li Z. Pyruvate kinase M2 accelerates pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and cell proliferation induced by lipopolysaccharide in colorectal cancer. Cell Signal. 2015;27:1525–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee I, Kim HK, Kim JH, Chung K, Chung JM. The role of reactive oxygen species in capsaicin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and in the activities of dorsal horn neurons. Pain. 2007;133:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Di W, Shi X, Lv H, Liu J, Zhang H, Li Z, Fang Y. Activation of the nuclear factor E2-related factor 2/anitioxidant response element alleviates the nitroglycerin-induced hyperalgesia in rats. J Headache Pain. 2016;17:99. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0694-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo D, Gu J, Jiang H, Ahmed A, Zhang Z, Gu Y. Inhibition of pyruvate kinase M2 by reactive oxygen species contributes to the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;91:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.