Summary

Objective

Histopathological grading of osteochondral (OC) tissue is widely used in osteoarthritis (OA) research, and it is relatively common in post-surgery in vitro diagnostics. However, relying on thin tissue section, this approach includes a number of limitations, such as: (1) destructiveness, (2) sample processing artefacts, (3) 2D section does not represent spatial 3D structure and composition of the tissue, and (4) the final outcome is subjective. To overcome these limitations, we recently developed a contrast-enhanced μCT (CEμCT) imaging technique to visualize the collagenous extracellular matrix (ECM) of articular cartilage (AC). In the present study, we demonstrate that histopathological scoring of OC tissue from CEμCT is feasible. Moreover, we establish a new, semi-quantitative OA μCT grading system for OC tissue.

Results

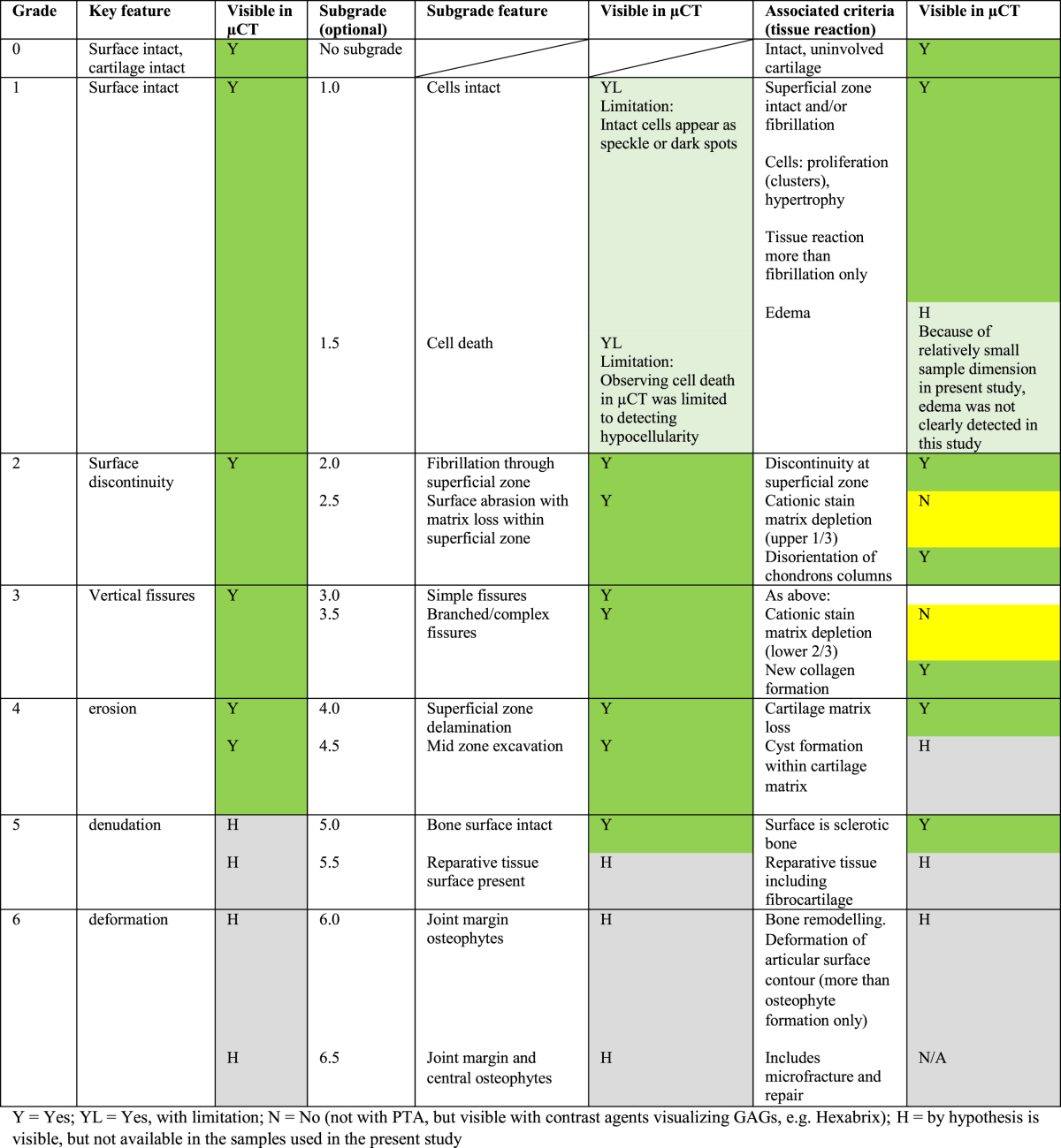

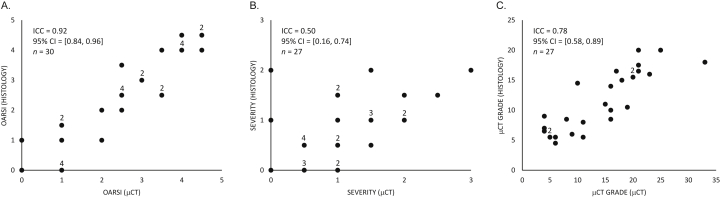

Pathological features were clearly visualized in AC and subchondral bone (SB) with μCT and verified with histology, as demonstrated with image atlases. Comparison of histopathological grades (OARSI or severity (0–3)) across the characterization approaches, CEμCT and histology, excellent (0.92, 95% CI = [0.84, 0.96], n = 30) or fair (0.50, 95% CI = [0.16, 0.74], n = 27) intra-class correlations (ICC), respectively. A new μCT grading system was successfully established which achieved an excellent cross-method (μCT vs histology) reader-to-reader intra-class correlation (0.78, 95% CI = [0.58, 0.89], n = 27).

Conclusions

We demonstrated that histopathological information relevant to OA can reliably be obtained from CEμCT images. This new grading system could be used as a reference for 3D imaging and analysis techniques intended for volumetric evaluation of OA pathology in research and clinical applications.

Keywords: Micro-computed tomography, Imaging, Osteoarthritis, Histology, Pathology

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) exhibits morphological and macromolecular changes in articular cartilage (AC) and subchondral bone (SB) as well as mild chronic inflammation in the synovium1. Because of these micro- and macrostructural changes in the structure and composition of osteochondral (OC) tissue, it has become common practice to visually evaluate the degenerative state of AC and SB based on optical imaging of stained tissue sections under the light microscope. The sections are typically stained with optical stains (e.g., hematoxylin & eosin (H&E), toluidine blue, Masson's trichrome, safranin O, picrosirius red)2 for histopathological evaluation. Based on visual evaluation criteria, scoring methods, such as grading Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) grading3, Mankin score4, O'Driscoll score5, 6, International Cartilage Repair Society scores (ICRS I7 and ICRS II8), aim to provide a semi-quantitative grade that represents tissue degeneration in the OC tissue. Typically, different features associated with tissue reaction or disease progression are separately graded and often summed as a final score. While these methods are widely employed, they have limitations, such as: (1) destructiveness including sample processing artifacts, (2) one or even several consecutive 2-dimensional (2D) sections represent only local degeneration in those sections (3), 2D section does not represent spatial 3-dimensional (3D) structure and composition, and (4) the final outcome is subjective.

Currently, 3D micro-level imaging technologies, based on optics9, sound10, 11, ionizing radiation12 and magnetic resonance13, can visualize relatively large tissue volumes (millimeters to centimeters). Such technologies could provide significant benefits over conventional section-based histopathology, such as: (1) minimal destructiveness, (2) no sectioning artefacts and (3) assessment of volumes (3D tissue structure, and composition). Moreover, digital data could potentially be automatized for reader-independency. Importantly, such 3D approaches could serve as a reference to 3D clinical imaging modalities relevant for OA, such as MRI14, cone-beam computed tomography (CT)15 and ultrasound16.

Future candidates for 3D micro-level imaging, which permit histopathological evaluation of OC structure, include optical coherence tomography (OCT)9, photo-acoustic imaging11, ultrasound biomicroscopy (USBM)10, scanning electron microscopy (SEM)17, transmission electron microscopy (TEM)18, and micro-magnetic resonance imaging (μMRI)13. However, currently their resolution and contrast mechanism are either insufficient to visualize structural or compositional details reliably in a large volume (few mm3) with sub-cellular resolution (1–10 μm) or they essentially miss one spatial dimension (SEM, TEM). Confocal microscopy19, can visualize fine details in 3D at micrometer scale, but light penetration into tissue is limited to ∼100 μm permitting only limited access into the AC volume.

We recently developed a contrast-enhanced micro-computed tomography (CEμCT) method to image AC12. This technique employs phosphotungstic acid (PTA) as a contrast agent that primarily bonds ionically with collagen in a low pH environment. Because PTA contains tungsten, it attenuates X-rays and, therefore, provides contrast to visualize structure and composition of the collagenous extracellular matrix (ECM). The spatial resolution of CEμCT can be smaller than the chondrocyte dimensions (<10 μm); therefore CEμCT potentially enables imaging of OC histopathology. Compared to conventional histology, this approach requires no decalcification of the tissue and, therefore, it also permits comprehensive evaluation of calcified tissues. There are a few limitations in CEμCT including relatively long imaging times (tens of minutes to hours), the requirement of contrast agents to visualize soft tissues and the cost of the technology.

The aims of this study were to:

-

(i)

identify morphological features of degenerated OC tissue that are visible on CEμCT,

-

(ii)

demonstrate that histopathological grading from CEμCT images is feasible (OARSI grade and severity score), and

-

(iii)

propose a new μCT grading system for OC tissue including comprehensive image atlases. The rationale for establishing a μCT grading system, is that 3D digital imaging potentially provides future means to quantify, user-independently, different OA features in large tissue volumes.

Materials and methods

Samples

Human OC cylinders (n = 30, diameter = 4.0 mm) were surgically excised from the femoral condyle (n = 15, one sample per joint) and from the tibial plateau (n = 15, one sample per joint) of 15 patients (age range: 51–89 years) undergoing total knee arthroplasty (ethics approval PPSHP 78/2013; consents obtained). One quarter per OC cylinder was randomly selected and subjected to the experiments in this study. This procedure was applied to (1) minimize the spatial sample size in order to maximize the spatial resolution in the μCT volume (sample dimensions affect the geometric magnification) and (2) to minimize the PTA staining time by minimizing the PTA diffusion path to the sample center.

CEμCT

The samples underwent formalin-fixation for 5 days. This was followed by immersion in 70% EtOH containing 1% w/v PTA for 48 h to achieve PTA staining of AC. The samples were then imaged with μCT using X-ray attenuation as contrast mechanism (Nanotom 180NF, Phoenix X-ray Systems/GE; 80 kV, 150 μA, 1600 projections, 750 ms/frame, 5 frames/projection, isotropic 3.0 μm voxel). The obtained projections were then reconstructed into volumes using datos|x (version 1.3.2.11, GE Measurement & Control Solutions/Phoenix X-ray, Fairfield, CT, USA).

Conventional histology

PTA was removed from the CEμCT samples prior to histopathological evaluation: samples were washed for 5 days in pH ∼10 solution, i.e., ion-exchanged water containing 0.1 M/L of Na2HPO4, 137 mM/L NaCL, 2.7 mM/L KCL, and 0.55 mM/L NaOH. The samples were subsequently decalcified for 17–18 days. This was followed by paraffin-embedding and preparation of each sample into 5 μm sections (at ∼200 μm spacing throughout the sample block). The sections were then stained with safranin O20, H&E21 or picrosirius red21 (see Supplement I for stain descriptions) and then subjected to light microscopy (LM): 1× microscope slide scanner (Pathscan Enabler IV, Meyer Instruments, Houston, TX, USA) and 40× LM (Aristoplan, Ernst Leitz Wetzlar, Wetzlar, Germany) with digital camera (MicroPublisher 5.0 RTV, Qimaging, Surrey, BC, Canada). The demonstrative histology images (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4) were subjected to minor histogram stretching, which was linear, manual, and subjective (same settings per stain in each figure).

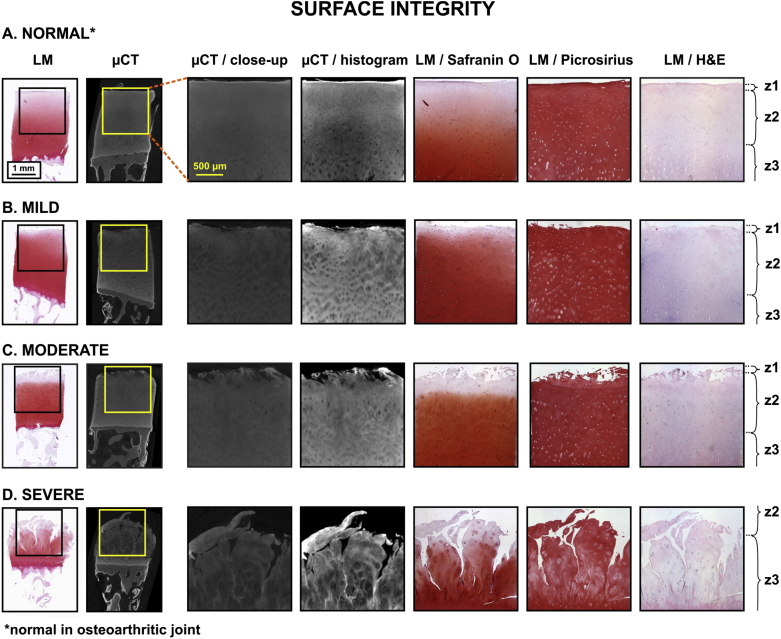

Fig. 1.

Image atlas for Surface integrity of human OC tissue as detected with CEμCT (μCT or μCT with histogram stretching for enhanced contrast) or optical LM of stained tissue sections (safranin O, picrosirius, and H&E) in different samples with different OA severity: A. normal, B. mild, C. moderate, and D. severe. Similar surface morphology of AC was present in μCT compared to histological sections. Labels: z1 = zone 1, i.e., superficial AC, z2 = zone 2, i.e., middle zone, z3 = zone 3, i.e., deep AC.

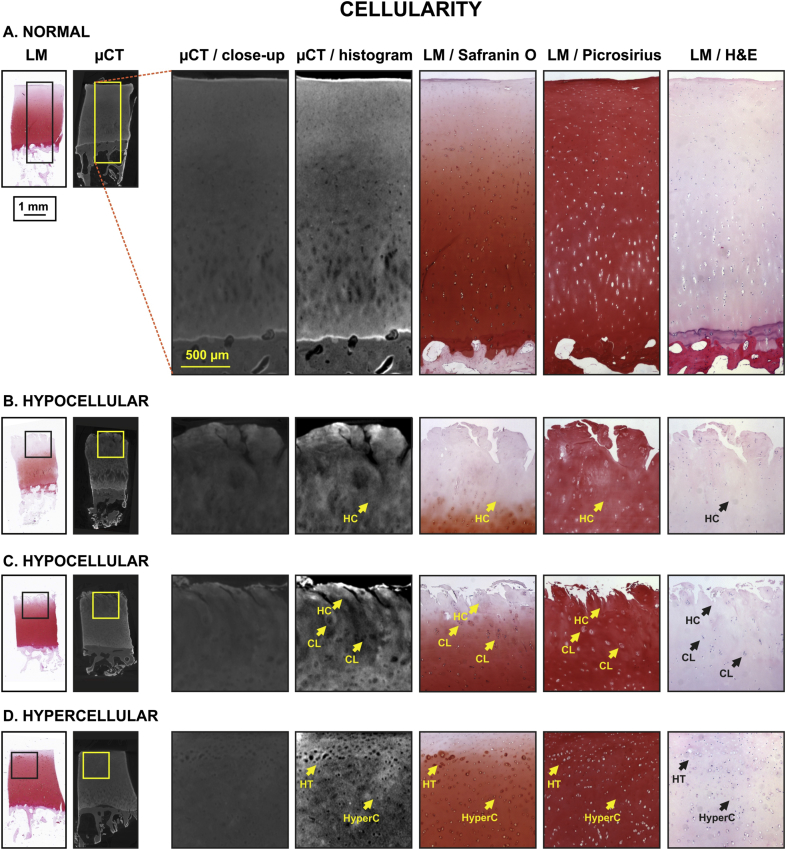

Fig. 2.

Image atlas for Cellularity of human OC tissue as detected with CEμCT (μCT or μCT with histogram stretching for enhanced contrast) or LM of stained tissue sections (safranin O, picrosirius, and H&E). The exemplary samples exhibited no pathological cells (A.), hypocellularity (B., C.), clustering (C.), hypertrophy (D.) or hypercellularity (D.). Similar cell characteristics were identifiable in μCT compared to histology, with the following limitations: some cells in μCT appear as speckle rather than individual cells. Labels: HC = hypocellular, CL = clustering, HT = hypertrophic, HyperC = hypercellular.

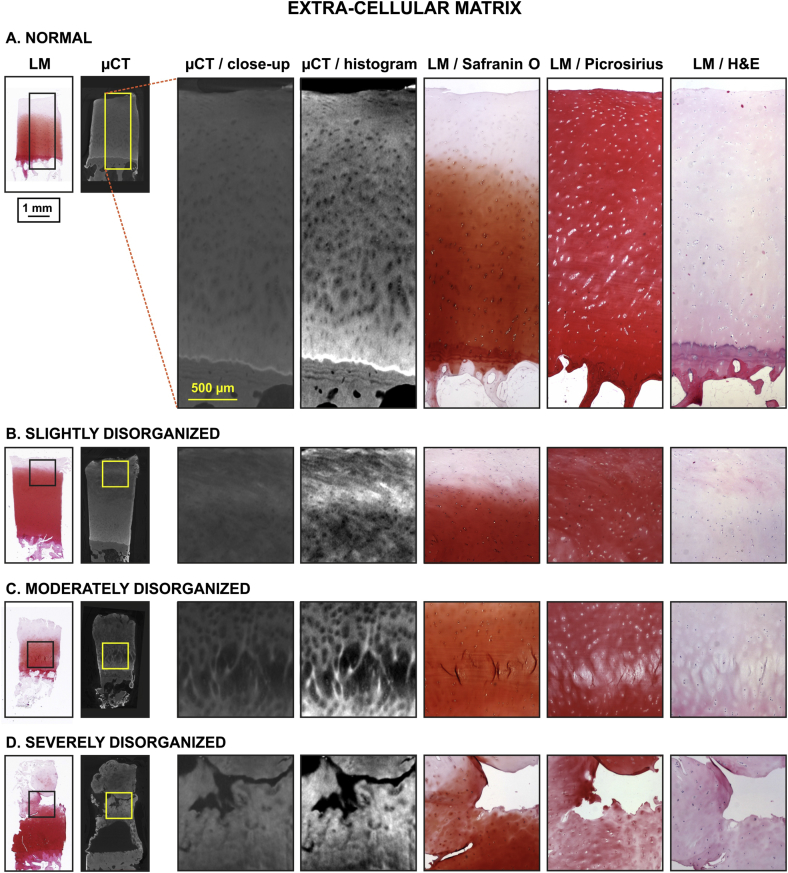

Fig. 3.

Image atlas for ECM organization of human OC tissue as detected with CEμCT (μCT or μCT with histogram stretching for enhanced contrast) or LM of stained tissue sections (safranin O, picrosirius, and H&E). μCT was efficient in visualizing the heterogeneity of ECM in normal ECM (A) to severely disorganized ECM (D), potentially more sensitive than histology.

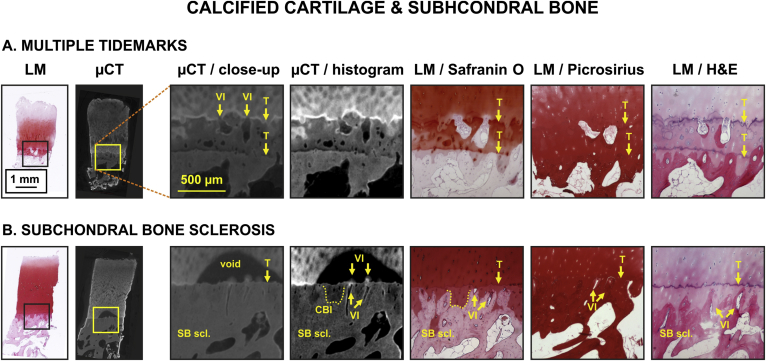

Fig. 4.

Image atlas for Calcified cartilage and SB changes in human OC tissue as detected by CEμCT (μCT or μCT with histogram stretching for enhanced contrast) or LM of stained tissue sections (safranin O, picrosirius, and H&E). μCT visualized clearly vascular infiltration (VI), tidemark (T), multiple tidemarks and SB sclerosis (SB scl.) (A. and B.). While not very clear, the cartilage-bone interface (CBI) was also visible in μCT (B.). As reported before12, we also in this study observed a contrast void near the tidemark in the μCT image (B.), corresponding to a slow diffusion area for the contrast agent (potentially due to high proteoglycan content in this region). The information complementary to conventional histology is the clear visualization of vascular infiltration, i.e., contrast agent diffuses from SB into cartilage through blood vessel cavities and into the void highlighting the locations of diffusion (B., VI + arrows pointing downwards).

Conventional histopathological scoring: μCT and LM

To demonstrate the capability of CEμCT images to serve as source images for histopathological grading, we first graded the μCT image stacks according to OARSI grading criteria on consensus basis (S.S., L.R., S.S.K.). The grading was applied by viewing all images of a 3D image stack that covered the entire tissue block. OARSI grading was then conducted for histology sections obtained from the same tissue block (S.S., L.R., S.S.K.). Similarly, the overall severity of degeneration was scored on a 0–3 point scale (scale: normal = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2, severe = 3) for samples characterized with both CEμCT (H.K.G.) and histology (H.K.G.) approaches. The OARSI grades obtained with different imaging methods were compared using intra-class correlation (ICC) analysis, i.e., ICC(3,1) (individual agreement). The samples were assumed to be randomly obtained from a large population and method was considered to be a fixed effect. Similar correlation analysis was repeated for the severity score. The micro-CT images were subjected to histogram stretching, which was linear, manual, and subjective, to visualize pathological features of interest.

Establishment of new μCT grading system

Histopathologically relevant morphological features of OC tissue were identified in μCT images based on authors' pathology expertise and features described in OARSI grading (Table III in Pritzker et al.3). Based on the examination of μCT images and using the reference histology, the new μCT grading system for osteoarthritic OC tissue was established with representative image atlases for separate features. The grading system aimed for evaluating morphology associated with both OA progression and OA activity. The system featured sub-components for specific assessment.

Validation of μCT grading system

The established μCT grading system was applied to grade all samples from the μCT image stacks (H.N.). The grading was applied by viewing all images of a 3D image stack that covered the entire tissue block. Subsequently, the same new grading system was applied to microscopy and histology sections by a blinded independent reader (H.K.G.). The agreement between the μCT grades obtained with different imaging methods were quantified by ICC(3,1) analysis similar to what described for OARSI and severity score.

Results

Conventional histopathological scoring

Pathological features associated with superficial AC, fibrillation, fissures, cellularity, ECM heterogeneity, fibrous tissue, vascular infiltration, tidemark and SB were identified in μCT (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). The AC lesions revealed by μCT were visually comparable to those observed in histology (Table I). Comparison of OARSI grading from μCT and histology sections revealed an excellent agreement (ICC = 0.92, 95% CI = [0.84, 0.96], n = 30) [Fig. 5(A)]. Similarly, a comparison for the severity score (μCT vs histology sections) showed a fair agreement (ICC = 0.50, 95% CI = [0.16, 0.74], n = 27) [Fig. 5(B)]. Based on this evaluation, the establishment of μCT grading criteria was considered possible.

Table I.

Pathological features defined in OARSI grading that are visible in CEμCT using PTA

Fig. 5.

Excellent ICC between the OARSI grade evaluated from conventional histopathology and OARSI grade evaluated from CEμCT was observed (same three readers in both methods) (A.). Similarly, a fair ICC between the severity score (normal = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2, severe = 3) evaluated from histology and μCT was demonstrated (same reader in both methods) (B.). The μCT score evaluated from μCT images by one reader and the μCT score evaluated form histology sections by a second blinded reader demonstrated an excellent ICC (C.). These results altogether (A.–C.) suggest that histopathological scoring from μCT images is possible and feasible. The number of overlapping data points has been indicated adjacent to such data points.

Description of μCT grading criteria

Based on the histopathological features visible in μCT, μCT grading criteria were established (Table II). The possible μCT grade values ranged from 0 (normal) to 42 (highest grade of Severe OA). We present in the following the evaluation criteria for the established μCT grading system.

Table II.

The CEμCT grading criteria of OA. The detailed description of the grading criteria is presented in Appendix I

| OA μCT grading system in OC plugs (v.1.0) | |

|---|---|

| A. AC surface | B. AC – zone 1 |

| Surface structure (continuity) | Cellularity |

| Smooth and continuous (0) | Normal (0) |

| Slightly discontinuous (1) | Diffuse hypercellular (1) |

| Moderately discontinuous (2) | Cloning/clustering (2) |

| Severely discontinuous (3) | Hypocellular (3) |

|

Fibrillation(s) Absent (0) Few (1) Several (2) Fissure(s) Absent (0) Present (1) Fibrous tissue Absent (0) Present (1) |

|

| C. AC – zone 2 | D. AC – zone 3 |

| Cellularity | Cellularity |

| Normal (0) | Normal (0) |

| Diffuse hypercellular (1) | Diffuse hypercellular (1) |

| Cloning/clustering (2) | Cloning/clustering (2) |

| Hypocellular (3) | Hypocellular (3) |

| ECM | ECM |

| Normal (0) | Normal (0) |

| Slightly disorganized (1) | Slightly disorganized (1) |

| Moderately disorganized (2) | Moderately disorganized (2) |

| Severely disorganized (3) | Severely disorganized (3) |

| Fissure(s) | Fissure(s) |

| Absent (0) | Absent (0) |

| Present only Z2 upper half (1) | Present only Z3 upper half (1) |

| Present up to Z2 lower half (2) | Present up to Z3 lower half (2) |

| Fibrous tissue | Fibrous tissue |

| Absent (0) | Absent (0) |

| Present – focal area (1) | Present – focal area (1) |

| Present – throughout (2) | Present – throughout (2) |

| E. AC – zone 4 | F. Tidemark |

| ECM | Present – only one (0) |

| Normal (0) | Multiple (1) |

| Slightly disorganized (1) | |

| Moderately disorganized (2) | G. SB evaluation |

| Severely disorganized (3) | Subchondral sclerosis |

| Vascular infiltration | None (0) |

| No vascularization (0) | Mild (1) |

| Mild vascularization (1) | Moderate (2) |

| Moderate vascularization (2) | Severe (3) |

| Severe vascularization (3) | |

| Fibrous tissue | |

| Absent (0) | |

| Present – focal area (1) | |

| Present – throughout (2) | |

Surface structure

Integrity/continuity: Early signs of OA include fraying and softening of the cartilage surface.

-

•

Smooth and continuous: Refer to intact, uninvolved superficial AC (zone 1) which appears smooth and without indentations.

-

•

Slightly discontinuous: AC features few protrusions attributed to cartilage surface edema, which occurs in early OA.

-

•

Moderately discontinuous: AC surface appears discontinuous due to presence of fibrillation throughout the zone 1 and simple fissures extending to the upper part of zone 2.

-

•

Severely discontinuous: AC shows superficial zone fraying and delamination with extensive, branched fissures extending deep into the zone 2/zone 3 with extensive ECM loss.

AC – zones 1, 2, 3

AC is heterogeneous and its material properties change as a function of depth. Based on its morphology and biochemical constitution, uncalcified AC features three zones (1–3): superficial zone (or lamina splendens), middle (or transitional) zone, and deep (or radial) zone. The fourth zone, which is subjacent to the tidemark, is the calcified cartilage zone.

-

•

Cellularity: Chondrocyte hypercellularity and cloning or clustering indicates an attempt to repair the injured/degraded ECM; whereas hypocellularity is a consequence of chondrocytic necrosis and/or apoptosis (cell death).

-

•

ECM (structural integrity): Progression of ECM degradation (Slight, moderate or severely disorganized) along its depth (zones) provides an index of the OA severity. This appears as heterogeneity or loss of organization.

-

•

Fibrillation and fissure(s): Mild damage occurs as fibrillation or fissures, which are restricted to the cartilage surface; whereas, severe damage involves full thickness loss of cartilage and damage to the underlying bone.

-

•

Fibrous tissue: Normal AC mainly consists of collagen Type II and proteoglycans. However, in an attempt to repair damaged AC, fibrous tissue can be formed, which is composed of collagen types I and III.

Calcified AC – zone 4

-

•

ECM (structural integrity): The calcified cartilage can be normal, slightly, moderately or severely disorganized.

-

•

Vascular infiltration: Blood vessels are absent from normal adult AC. However, channels containing cellular elements, including blood vessels, invade from the SB into the calcified cartilage and breach the tidemark in OA. Vascular invasion of the calcified cartilage zone is a critical component in the progression of OA.

-

•

Fibrous tissue: In an attempt to repair damaged AC, fibrous tissue can be formed.

Tidemark integrity

Structural changes in the osteoarthritic AC include tidemark duplication and multiplication.

SB integrity

Structural changes in the OA SB includes subchondral sclerosis. SB sclerosis seen with progressive cartilage degradation is considered to be the hallmark of OA most commonly seen in late-stage OA. Subchondral sclerosis is a repair response to injury that results in increased bone density and thickening in the subchondral layer of a joint. There is a positive association between the subchondral sclerosis and OA severity.

If a zone was missing, maximum sub-scores associated with that zone were given.

Validation of μCT grading criteria

The μCT grading was finally validated by comparing the μCT scores obtained by one reader using μCT volumes with μCT scores obtained by a blinded reader using histology sections; this comparison yielded an excellent agreement (ICC = 0.78, 95% CI = [0.58, 0.89], n = 27) [Fig. 5(C)].

Discussion

Morphological features relevant to OA were identified by CEμCT and verified against conventional histopathology (Table I, Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). These features included surface discontinuity, fibrillation, fissures, AC excavation, cellularity (chondrocyte clustering, hypocellularity, hypercellularity, cell hypertrophy, and chondron hypertrophy), disorganization of ECM, fibrous tissue, vascular infiltration, tidemark (also duplicate and multiple tidemarks), and subchondral changes such as bone sclerosis. Regarding the morphological and compositional features described in the OARSI grading system (Table III in Pritzker et al.3), μCT provides means to identify all key features and most subgrades and associated features of the OARSI (see Table I). This explains the observed excellent agreement between OARSI grades determined by μCT and by histology (ICC = 0.92, 95% CI = [0.84, 0.96], n = 30). Our initial hypothesis that CEμCT images could be used for 3D histopathological grading is further supported by fair agreement (ICC = 0.50, 95% CI = [0.16, 0.74], n = 27) between the severity score determined from μCT images and conventional histology.

While the OARSI histopathological grading system was originally established by relying on principles of simplicity, utility, scalability, extendability, and comparability, our new μCT grading system aims to provide 3D morphological details in a large tissue volume to study relationships between OA progression and OA activity in AC and underlying SB. Moreover, as the μCT data is 3D, it supports development of user-independent analysis tools, e.g., based on image analysis and artificial intelligence, to quantify features associated with OA activity and progression. Importantly, μCT provides information complementary to that provided by standard histology. This is because the μCT approach is less destructive and requires no decalcification and virtual tissue sections can be generated in any orientation. This is different from standard histology that is destructive, requires decalcification, and where tissue is cut irreversibly typically along a single orientation. According to our knowledge, histopathological evaluation of AC and SB has not previously been conducted based on 3D μCT data, even though many studies have used 3D μCT data to evaluate their characteristics22, 23, 24, 25, 26.

Since histopathological grading was found to be feasible and reliable when based on the CEμCT images, we established a new μCT grading system for evaluation of pathological features in AC and SB. The system exhibited excellent cross-method inter-reader agreement (μCT vs histology, ICC = 0.78, 95% CI = [0.58, 0.89], n = 27), which further validates this grading system. The rationale for establishing a new μCT grading system is to provide access to pathological features associated with OA activity and progression3 from 3D data recorded digitally. This grading system could serve as a pathological reference for future 3D applications assessing OA pathology based on volumetric data.

There were minor discrepancies between μCT and histology grades, which we consider to arise from limitations either in conventional histopathological grading or in μCT imaging: (1) histological sections cover only a limited portion of the entire tissue volume; thus, some pathologically relevant features can be missed; (2) conventional histology is subjected to core drilling and tissue sectioning artifacts, whereas μCT is subjected only to core drilling artifacts; (3) the chosen sample dimensions (sample size affects the spatial resolution of μCT due to geometric magnification) for μCT imaging result in spatial resolution inferior to optical microscopy (individual cells in histology appear sometimes as speckle in μCT; minor fibrillation can be of sub-voxel sized and, thus, not visible); (4) the anionic PTA does not provide the information provided by the cationic stain preferred in OARSI grading. However, this could be overcome by applying a negatively charged X-ray contrast agent such as ioxaglic acid or gadopentetate dimeglumine27; and (5) with μCT, one can browse the image stack virtually along any dimension to exclude potential artifacts arising e.g., from sample preparation – something that is impossible with standard histology. Despite the minor shortcomings, the information in both imaging modalities, microscopy and μCT, are essentially the same as demonstrated by the excellent or fair ICC for OARSI grade and severity score, respectively. Based on the above reasoning, we conclude that OARSI grading and severity scoring based on CEμCT images is possible and provides a reliable way to evaluate AC degeneration. Since the lower 95% CI boundary of ICC (histology vs μCT) for OARSI grade was excellent, i.e., 0.84, clinical applicability of OARSI grading in vitro from μCT volumes can already be foreseen. The rather wide 95% CIs in μCT score or severity may be associated with using single readings by single readers, instead of consensus by 3 readers, leaving more space for subjective interpretations.

As reported PTA does not always penetrate all the way to the tidemark12 (Fig. 3(D), zone 3; Fig. 4(B), zone 3). High proteoglycan content slows down diffusion of molecules from AC surface towards deep tissue and from sides towards the center of the OC plug22, 28, which might explain that the PTA does not have sufficient time to reach all parts of the AC, especially near tidemark. This might explain the observed voids. Therefore, these voids might be indicators of high proteoglycan content in these regions. Moreover, the void provides clear visualization of vascular infiltration, when PTA diffuses through blood vessel cavities within SB extruding into the boundary of the void near calcified AC. This extrusion shows as a bright contrast against dark contrast of the void [Fig. 4(B)], which makes the vascular infiltration clearly visible and easily detectable.

Limitations of this study include the following: One sample out of 30 lacked the SB as confirmed in μCT and histology. Four out of 30 samples featured partial detachment of AC from the calcified cartilage or SB (laterally about 5–70% of full OC plug width) as confirmed in μCT or histology. This detachment artifact may relate to sample preparation, formalin fixation or PTA-staining. Shrinkage of soft tissue induced by aldehyde-based fixatives is widely recognized29, 30, 31, 32, also in OC tissue33. Considering (1) that ethanol was used as base medium in PTA staining, and (2) that ethanol may contribute to AC deformation33, 34, PTA-staining-induced deformation of AC may not be excluded. However, as can be seen in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, major differential lateral shrinkage of SB/non-calcified AC vs calcified AC was not observed in μCT suggesting that the deformation is not histopathologically significant. Furthermore, one technical limitation of the study is potential bias in histology staining due to possible PTA residues in AC after PTA washout, although not found significant during preliminary experiments. Another limitation relates to diffusion of PTA into the bone: the rate of diffusion of PTA into the bone appears significantly slower than in AC. Therefore, PTA induces a thin high contrast boundary in μCT in regions, where PTA had been in direct contact with bone (e.g., Fig. 4). Where PTA does not penetrate into the bone (most of the calcified tissues), bone can be subjected to μCT-based evaluation of SB characteristics relevant to its pathology25, 26. It is, however, a limiting factor that the X-ray attenuation contrast can be compromised when identifying the boundary between calcified AC and SB (Fig. 4), when assessing e.g., the thickness of the SB plate.

In terms of time and economy, the proposed 3D-histopathological grading in the clinic would have advantages and disadvantages compared to conventional section-based histopathological grading. In principle, the proposed method can provide short duration from tissue extraction to analysis: following 5-days formalin fixation, the PTA-staining would take 2 days followed by 2–3 h for imaging and reconstruction; for one sample this would yield a nominal 1–1.5 weeks from extraction of a sample to obtain the data set. To generate similar data for conventional histology (considering the protocols applied in this study), one would require 5-days formalin fixation, 2–3 weeks decalcification, followed by 1 day for paraffin embedding, sectioning, staining and microscopy/imaging; this would yield a nominal 3–4 weeks form tissue extraction to analysis for one sample. While standard histology equipment would be relatively inexpensive, a μCT system capable to achieve a resolution equivalent to that in this study can be several times the cost of conventional histology equipment. However, with rather rapid detector development (greater detector element density; greater sensitivity yielding shorter exposure times), the price-to-resolution ratio is expected to improve. Nevertheless, in spite of the higher cost, the μCT approach provides several major advantages compared conventional histology, as elaborated in the following.

The high-resolution and high contrast provided by the used μCT system and CEμCT protocol offers a comprehensive approach to volumetrically evaluate OA lesions. It also offers easy use for browsing large image stacks slice-by-slice, analogous to viewing clinical MRI or CT image stacks. Clinical in vitro diagnostics and OA research would benefit e.g., from the reduced bias from sample preparation artifacts and possibility to significantly increase the number of “histology sections” to provide more representative data. Particularly, the strengths of the μCT grading approach include:

-

(i)

minimal destructiveness compared to conventional histology, e.g., no sectioning artifacts,

-

(ii)

assessment of volumes (3D tissue structure and composition) instead of cross-sections representing small volumes,

-

(iii)

no decalcification is required (provides information about calcification that is complementary to conventional histology, which requires decalcification), and

-

(iv)

the approach is time-efficient (samples can be assessed within days instead of weeks from extraction).

In the future, once the cost of μCT technology is reduced and the detection of small structures, like cells, is improved, there would be compelling reasons to replace some conventional histopathology diagnostics by 3D-histopathology using μCT. Importantly, the digital μCT data could potentially be computerized and automated for reader-independent histopathological evaluation tools, a subject for our future research.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that histopathological evaluation of OC tissue is feasible and reliable using 3D CEμCT images. Furthermore, we established a new μCT grading system, which could serve as a 3D reference for developing volumetric image analyses of OC tissue, for both in vitro and in vivo applications. In future, this μCT grading system could replace some of the standard histological methods that suffer greatly from sampling issues.

Author contributions

H.J.N., H.K.G., K.P.H.P., S.K., T.Y., P.L., and S.S. contributed to the conception and design of the study. H.J.N., H.K.G., K.P.H.P., S.K., T.Y., L.R., P.L., E.H. and S.S. participated in acquisition and analysis of the data. All authors contributed to interpreting the data, drafting or revising the manuscript, and have approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

H.J.N., T.Y., E.H., and S.S. are inventors in a patent application related to image analysis of AC. Other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Role of the funding source

Funding sources are not associated with the scientific contents of the study.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Academy of Finland (grants no. 268378 and 273571); European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007–2013)/ERC Grant Agreement no. 336267; and the strategic funding of the University of Oulu are acknowledged. We thank Dr. Maarit Valkealahti for providing the human OC samples, Ms. Iida Kestilä and Mr. Sami Kauppinen for assistance in light microscopy and Ms. Tarja Huhta for preparing histology sections.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2017.05.021.

Contributor Information

H.J. Nieminen, Email: heikki.j.nieminen@aalto.fi.

H.K. Gahunia, Email: harpal.gahunia@utoronto.ca.

K.P.H. Pritzker, Email: kenpritzker@gmail.com.

T. Ylitalo, Email: tuomo.ylitalo@helsinki.fi.

L. Rieppo, Email: lassi.rieppo@oulu.fi.

S.S. Karhula, Email: sakari.karhula@oulu.fi.

P. Lehenkari, Email: petri.lehenkari@oulu.fi.

E. Hæggström, Email: edward.haeggstrom@helsinki.fi.

S. Saarakkala, Email: simo.saarakkala@oulu.fi.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

Comparison of histology sections (left) and μCT volume (slice-by-slice presentation, right) in osteochonral tissue with OARSI grade 4.

Comparison of histology sections (left) and μCT volume (slice-by-slice presentation, right) in osteochonral tissue with OARSI grade 4.5.

References

- 1.Buckwalter J.A., Mankin H.J., Grodzinsky A.J. Articular cartilage and osteoarthritis. Instr Course Lect. 2005;54:465–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyllested J.L., Veje K., Ostergaard K. Histochemical studies of the extracellular matrix of human articular cartilage – a review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;10:333–343. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pritzker K.P., Gay S., Jimenez S.A., Ostergaard K., Pelletier J.P., Revell P.A. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.07.014. S1063-4584(05)00197-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mankin H.J., Dorfman H., Lippiello L., Zarins A. Biochemical and metabolic abnormalities in articular cartilage from osteo-arthritic human hips. II. Correlation of morphology with biochemical and metabolic data. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53:523–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Driscoll S.W., Keeley F.W., Salter R.B. The chondrogenic potential of free autogenous periosteal grafts for biological resurfacing of major full-thickness defects in joint surfaces under the influence of continuous passive motion. An experimental investigation in the rabbit. J Bone Joint Surg Ser A. 1986;68:1017–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Driscoll S.W., Keeley F.W., Salter R.B. Durability of regenerated articular cartilage produced by free autogenous periosteal grafts in major full-thickness defects in joint surfaces under the influence of continuous passive motion. A follow-up report at one year. J Bone Joint Surg Ser A. 1988;70:595–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mainil-Varlet P., Aigner T., Brittberg M., Bullough P., Hollander A., Hunziker E. Histological assessment of cartilage repair: a report by the histology endpoint committee of the International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) J Bone Joint Surg Ser A. 2003;85:45–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mainil-Varlet P., Van Damme B., Nesic D., Knutsen G., Kandel R., Roberts S. A new histology scoring system for the assessment of the quality of human cartilage repair: ICRS II. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:880–890. doi: 10.1177/0363546509359068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Malley M.J., Chu C.R. Arthroscopic optical coherence tomography in diagnosis of early arthritis. Minim Invasive Surg. 2011;2011:671308. doi: 10.1155/2011/671308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schone M., Mannicke N., Somerson J.S., Marquass B., Henkelmann R., Mochida J. 3D ultrasound biomicroscopy for assessment of cartilage repair tissue: volumetric characterisation and correlation to established classification systems. Eur Cell Mater. 2016;31:119–135. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v031a09. vol031a09 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun Y., Sobel E.S., Jiang H. First assessment of three-dimensional quantitative photoacoustic tomography for in vivo detection of osteoarthritis in the finger joints. Med Phys. 2011;38:4009–4017. doi: 10.1118/1.3598113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nieminen H.J., Ylitalo T., Karhula S., Suuronen J.P., Kauppinen S., Serimaa R. Determining collagen distribution in articular cartilage using contrast-enhanced micro-computed tomography. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23:1613–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia Y. MRI of articular cartilage at microscopic resolution. Bone Joint Res. 2013;2:9–17. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.21.2000135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raynauld J.P., Martel-Pelletier J., Berthiaume M.J., Labonte F., Beaudoin G., de Guise J.A. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of knee osteoarthritis progression over two years and correlation with clinical symptoms and radiologic changes. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:476–487. doi: 10.1002/art.20000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kokkonen H.T., Suomalainen J.S., Joukainen A., Kroger H., Sirola J., Jurvelin J.S. In vivo diagnostics of human knee cartilage lesions using delayed CBCT arthrography. J Orthop Res. 2014;32:403–412. doi: 10.1002/jor.22521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moller I., Bong D., Naredo E., Filippucci E., Carrasco I., Moragues C. Ultrasound in the study and monitoring of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(Suppl 3):S4–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes L.C., Archer C.W., ap Gwynn I. The ultrastructure of mouse articular cartilage: collagen orientation and implications for tissue functionality. A polarised light and scanning electron microscope study and review. Eur Cell Mater. 2005;9:68–84. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v009a09. vol009a09 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Rosier D.J., Klug A. Reconstruction of three dimensional structures from electron micrographs. Nature. 1968;217:130–134. doi: 10.1038/217130a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Youn I., Choi J.B., Cao L., Setton L.A., Guilak F. Zonal variations in the three-dimensional morphology of the chondron measured in situ using confocal microscopy. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:889–897. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.02.017. S1063-4584(06)00047-1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiviranta I., Jurvelin J., Tammi M., Saamanen A.M., Helminen H.J. Microspectrophotometric quantitation of glycosaminoglycans in articular cartilage sections stained with safranin O. Histochemistry. 1985;82:249–255. doi: 10.1007/BF00501401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmitz N., Laverty S., Kraus V.B., Aigner T. Basic methods in histopathology of joint tissues. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(Suppl 3):S113–S116. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karhula S.S., Finnila M.A., Lammi M.J., Ylarinne J.H., Kauppinen S., Rieppo L. Effects of articular cartilage constituents on phosphotungstic acid enhanced micro-computed tomography. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lakin B.A., Grasso D.J., Shah S.S., Stewart R.C., Bansal P.N., Freedman J.D. Cationic agent contrast-enhanced computed tomography imaging of cartilage correlates with the compressive modulus and coefficient of friction. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mittelstaedt D., Xia Y. Depth-dependent glycosaminoglycan concentration in articular cartilage by quantitative contrast-enhanced micro-computed tomography. Cartilage. 2015;6:216–225. doi: 10.1177/1947603515596418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finnila M.A., Thevenot J., Aho O.M., Tiitu V., Rautiainen J., Kauppinen S. Association between subchondral bone structure and osteoarthritis histopathological grade. J Orthop Res. 2016 doi: 10.1002/jor.23312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts B.C., Thewlis D., Solomon L.B., Mercer G., Reynolds K.J., Perilli E. Systematic mapping of the subchondral bone 3D microarchitecture in the human tibial plateau: variations with joint alignment. J Orthop Res. 2016 doi: 10.1002/jor.23474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer A.W., Guldberg R.E., Levenston M.E. Analysis of cartilage matrix fixed charge density and three-dimensional morphology via contrast-enhanced microcomputed tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19255–19260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606406103. 0606406103 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maroudas A. Distribution and diffusion of solutes in articular cartilage. Biophys J. 1970;10:365–379. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(70)86307-X. S0006-3495(70)86307-X [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tran T., Sundaram C.P., Bahler C.D., Eble J.N., Grignon D.J., Monn M.F. Correcting the shrinkage effects of formalin fixation and tissue processing for renal tumors: toward Standardization of pathological reporting of tumor size. J Cancer. 2015;6:759–766. doi: 10.7150/jca.12094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boonstra H., Oosterhuis J.W., Oosterhuis A.M., Fleuren G.J. Cervical tissue shrinkage by formaldehyde fixation, paraffin wax embedding, section cutting and mounting. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1983;402:195–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00695061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jonmarker S., Valdman A., Lindberg A., Hellstrom M., Egevad L. Tissue shrinkage after fixation with formalin injection of prostatectomy specimens. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:297–301. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeap B.H., Muniandy S., Lee S.K., Sabaratnam S., Singh M. Specimen shrinkage and its influence on margin assessment in breast cancer. Asian J Surg. 2007;30:183–187. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(08)60020-2. S1015-9584(08)60020-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunziker E.B., Lippuner K., Shintani N. How best to preserve and reveal the structural intricacies of cartilaginous tissue. Matrix Biol. 2014;39:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunziker E.B., Schenk R.K. Physiological mechanisms adopted by chondrocytes in regulating longitudinal bone growth in rats. J Physiol. 1989;414:55–71. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Comparison of histology sections (left) and μCT volume (slice-by-slice presentation, right) in osteochonral tissue with OARSI grade 4.

Comparison of histology sections (left) and μCT volume (slice-by-slice presentation, right) in osteochonral tissue with OARSI grade 4.5.