Abstract

Climatic change is widely acknowledged to have played a role in the dispersal of modern humans out of Africa, but the timing is contentious. Genetic evidence links dispersal to climatic change ~60,000 years ago, despite increasing evidence for earlier modern human presence in Asia. We report a deep seismic and near-continuous core record of the last 150,000 years from Lake Tana, Ethiopia, close to early modern human fossil sites and to postulated dispersal routes. The record shows varied climate towards the end of the penultimate glacial, followed by an abrupt change to relatively stable moist climate during the last interglacial. These conditions could have favoured selection for behavioural versatility, population growth and range expansion, supporting models of early, multiple dispersals of modern humans from Africa.

Introduction

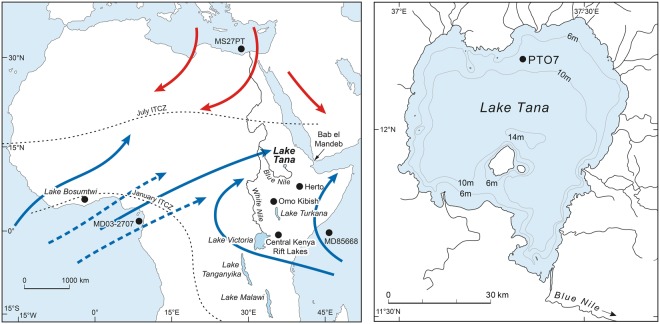

Understanding the role of climatic change in the emergence of Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans, AMH) in eastern Africa and their subsequent expansion into Asia requires continuous, well-dated terrestrial records for the relevant time range, currently lacking from the region. Palaeontological1–3 and genetic4,5 data indicate that AMH emerged around 200–300,000 years ago (ka), but there is much debate about the timing of their dispersal out of Africa6,7. Early dispersals during Marine Isotope Stage 5 (MIS 5; 130–90 ka) may be inferred from 90–120 kyr fossils in the Levant8,9, 80–120 kyr human teeth from Fuyan Cave, China10, 73–63 kyr teeth from Sumatra11, a 63 kyr cranium from Tam Pa Ling, Laos12, from neurocranial shape diversity13, and from stone artefacts at Jebel Faya, U.A.E., dated to 95–127 ka14. However, most phylogenetic estimates from living Eurasian populations point to their origin from a single late exodus at around 80–40 ka15,16 initiating AMH expansion across south Asia to Australia by ~65 ka17, although the data do not preclude earlier migrations whose lineages are now extinct18. Late AMH dispersal beyond Africa is sometimes linked to wetter, more stable climate at ~70 ka following episodes of severe aridity, apparent in the records from lakes Malawi, Tanganyika and Bosumtwi19. Those lakes are distant from and in different climatic regimes to the AMH fossil localities. In contrast, Lake Tana, northern Ethiopia, is close to the earliest eastern African AMH sites Herto1 and Omo Kibish2, and to postulated dispersal routes (Nile corridor, Saharan and Arabian watercourses20,21, Red Sea coasts and Bab el Mandeb strait14,22; Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Location and climatic context of Lake Tana. Blue arrows indicate paths of rain-bearing monsoon air masses in boreal summer, when the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ICTZ) moves northward. From October to May, the ITCZ shifts southwards and dry airflows dominate (red arrows). Marine and lacustrine core sites, earliest Homo sapiens sites (Herto, Omo), and Bab el Mandeb strait are also shown. (b) Position of core PT07 in Lake Tana at 12°N, 37° 15′ E. Maps generated in Adobe Illustrator CS6 Version:16.0.4. https://www.adobe.com/uk/.

Summer monsoon rains, derived from the Indian Ocean and from the Atlantic via the Congo Basin23, feed four perennial and numerous ephemeral rivers entering Lake Tana. At 1785 m on the Tertiary flood basalts of the Ethiopian plateau, the lake occupies a 60–80 km diameter steep-sided basin, interpreted as an Oligocene caldera24. At its only outflow, the Blue Nile crosses scoraceous basalt with an 40Ar/39Ar age of 33 ± 5 ka24. Runoff from these highlands contributes most of the lower Nile discharge and a vastly greater proportion of its transported sediment25. Desiccation of Lake Tana at the time of Heinrich Stadial 1 (H1, ~16 ka)26,27 coincided with drying of Lake Victoria, source of the White Nile28, underlining the sensitivity of the entire Nile basin to climate extremes.

Results

Seismic and geochemical data

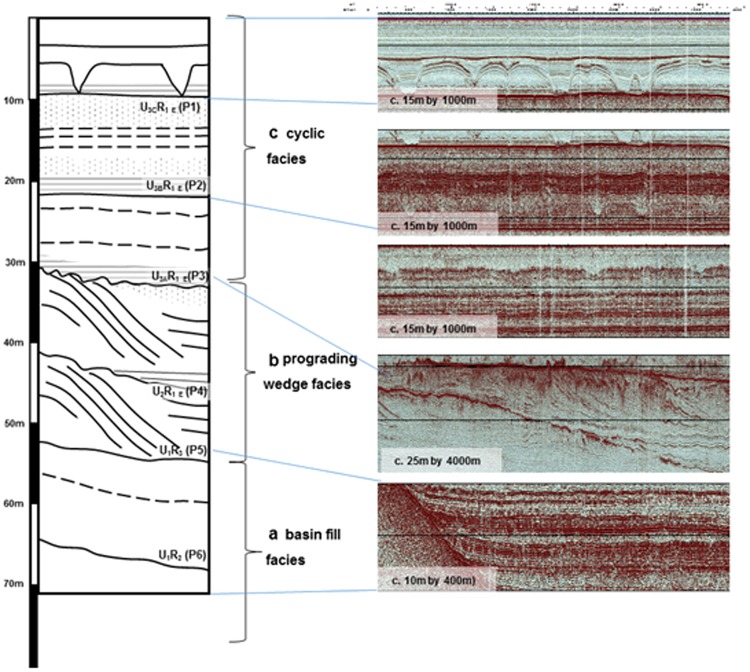

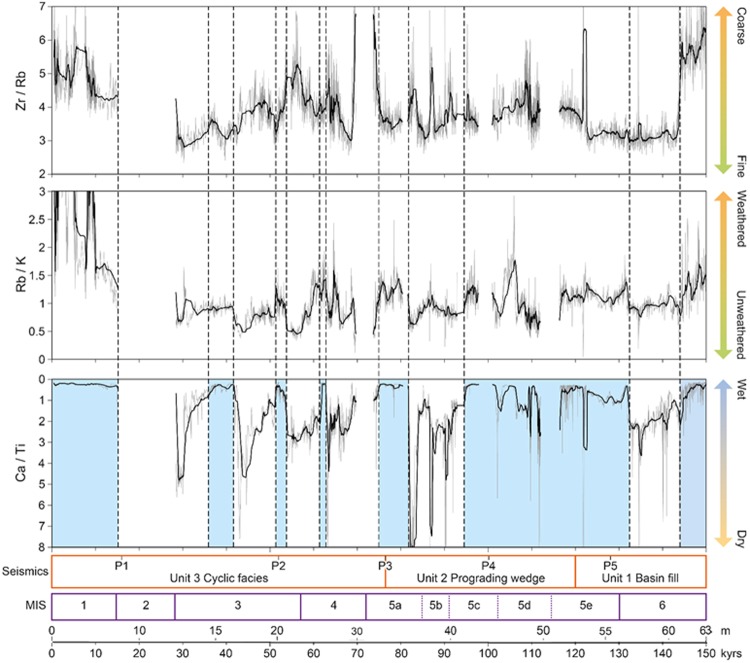

Seismic data from Lake Tana reveal >100 m of unconsolidated sediments punctuated by strong continuous reflectors, with no apparent faulting (Fig. 2; Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Fig. 1, 13–17; Supplementary Table 3). Three seismic units contain desiccation surfaces, truncated deltaic structures, and cut-and-fill features interpreted as channels, indicating a complex sedimentation history resulting from lake-level fluctuations. The deepest seismic unit 1 onlaps the acoustic basement, interpreted as basalt bedrock, and shows a sequence of basin fill with horizontal planar reflectors, succeeded by unit 2 in which the basin fill is disrupted by unconformities and prograding wedges. The uppermost seismic unit 3 shows a repeated sequence of fill with downcutting events similar to those reported previously in the section from 18 ka to present25,26. Core PT07-2 reached a depth of 91.8 m. Fifteen post-IR IRSL and four radiocarbon ages indicate that the core extends to 250 ka (Supplementary Methods). Overall core recovery was 80% with most of the missing sediments from below 63 mbss. We focus here on the uppermost 62.7 m, representing the last ~150 ka. The elemental ratios Zr/Rb, Rb/K and Ca/Ti (Fig. 3) may be interpreted as proxies for sediment grain size, degree of chemical weathering, and effective moisture (precipitation minus evaporation) respectively29. Ti is an unambiguous indicator of allochthonous inputs, so higher values of Ca/Ti identify within-lake Ca precipitation during evaporative concentration of the lake water, lower lake levels, and thus drier climate. The catchment erosion proxies Zr/Rb and Rb/K show elevated values since ~5 ka, probably as a result of anthropogenic disturbance. In contrast, low Holocene values of Ca/Ti indicate lake overflow conditions, making a useful baseline for interpreting the older record. Short-term variations in the data reflect the hydrological sensitivity of a shallow lake, and the proximity of the core site to the lake shore (Fig. 1b).

Figure 2.

Type-section data extracts of the three major seismic facies in the vicinity of core PT07. (a) Basin fill facies of unit 1 showing conformable strata onlapping onto seismic basement. (b) Wedge facies of unit 2, showing progradational phase. (c) Cyclic facies of unit 3 showing repeating reflectors, and pronounced cut-and-fill features. Reflector labels as in Supplementary Table 3. Only the uppermost 70 m of the >100 m seismic profile is shown here. Seismic acquired using SonatWiz, v5, Chesapeake Inc. (https://chesapeaketech.com/) and processed with Kingdom, IHS Markit https://kingdom.ihs.com/.

Figure 3.

Selected elemental ratios determined by Itrax® XRF scanning of core PT07 at 2 mm intervals, plotted as 25-point running means against a 150 kyr timescale and a non-linear depth scale, with approximate boundaries of the major seismic units and Marine Isotope Stages (MIS). Blue shading indicates intervals of predominantly high lake level. Note reversed scale for Ca/Ti ratios. Figure generated in Adobe Illustrator CS6 Version:16.0.4. https://www.adobe.com/uk/.

Within age uncertainties, the seismic and Ca/Ti data are mutually reinforcing, supporting an interpretation of climate-driven lake-level change (Fig. 3). The basin fill facies (seismic unit 1, ≥55 m, ≥120 ka), interpreted as deep-water sedimentation, corresponds to initially low Ca/Ti values (high lake-level) with relatively high input of coarse and weathered sediment. At ~144 ka grain size and weathering diminish abruptly and Ca/Ti increases, indicating a drying trend with reduced erosive input. Moisture increases abruptly at 132 ka, marking the onset of generally stable high lake-level conditions during MIS 5e to 5c (~132 ka to ~95 ka), punctuated by brief dry episodes. The corresponding seismic data show conformable infill, prograding wedge phases and unconformities. In combination, the data imply increased amount and intensity of rainfall during MIS 5e–5c, causing both high lake levels and increased sediment transport to the lake.

From ~95 ka until ~28 ka (MIS 5b to MIS 2) five asymmetric intervals of increasing aridity, typically lasting 8–12 kyrs, are each followed by an abrupt change to high lake levels, which last 2–5 kyrs. The oldest and longest of these dry-wet cycles, from ~95 to ~76 ka, shows the most extreme Ca/Ti variation, recording the driest episodes of the entire record. It corresponds to the most prominent prograding wedge complex in the seismic sequence (top of unit 2b), which lies above an erosive surface (reflector P3; Supplementary Table 3), indicating that low lake level was accompanied by erosion of the underlying sediments. Subsequently, sediment transport to the lake was enhanced by aridity and reduced catchment vegetation. This cycle concludes with wet, stable conditions of approximately 5 kyrs duration, the longest such interval in the cycle set. The subsequent asymmetric Ca/Ti cycles correlate to patterns of cyclicity in the seismic facies.

Regional comparisons

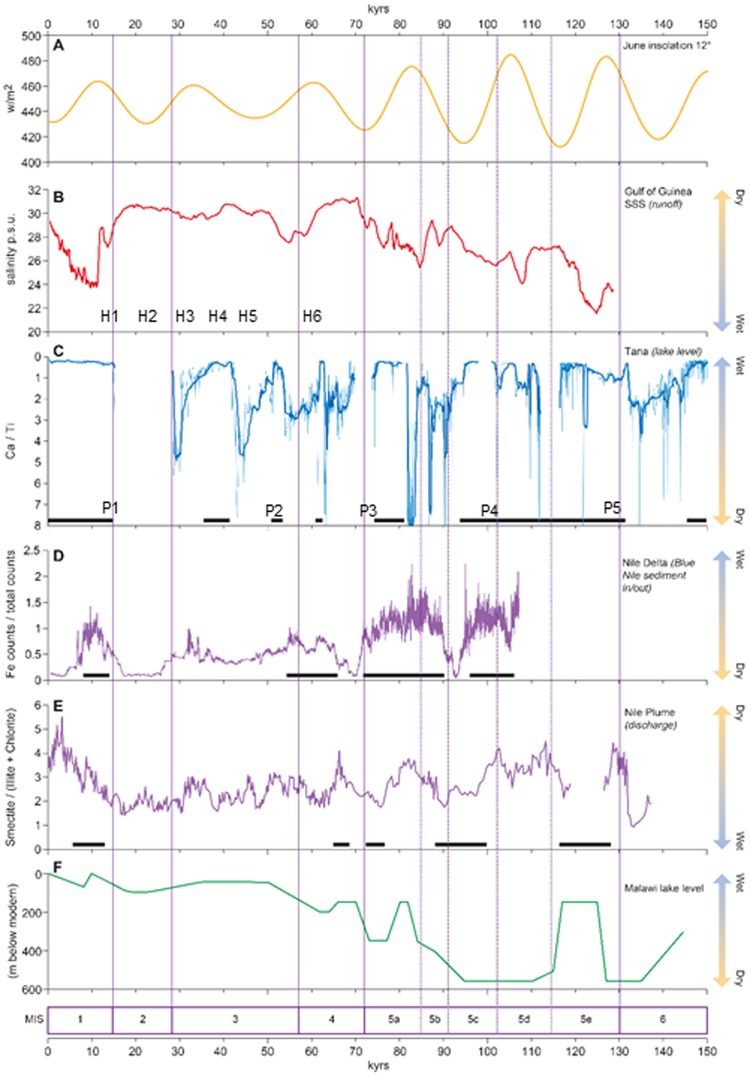

Regional expression of the climatic changes recorded at Lake Tana is evident from similar patterns of change in west Africa and in Nile discharge records from the delta and east Mediterranean Sea, where precession-driven insolation ultimately controls millennial-scale rainfall variation and Nile discharge respectively30–32 (Fig. 4). These comparisons are subject to chronological uncertainties and lack of independent dating in most other records. June insolation at 12°N shows maximum amplitude during the wettest interval (132–95 ka; MIS 5e–5c) at Lake Tana, fitting models in which strong insolation increases the temperature-pressure gradient between oceans and continent, thus intensifying the north African summer monsoon. Strong fluvial runoff into the Gulf of Guinea, reflected in lowered sea-surface salinity, is also apparent during this interval30. Stable hydrogen isotope composition of leaf waxes in a core from the Gulf of Aden also show moist conditions in northeast Africa during MIS 533. Rising values of Ca/Ti at ~82 ka indicate drought in the Blue Nile headwaters; runoff into the Gulf of Guinea was low at about the same time30.

Figure 4.

Regional expression of the climate changes at Lake Tana. (A) June insolation at 12° N. (B) Sea-surface salinity in the Gulf of Guinea, core MD03-270728. (C) Ca/ Ti ratios, Lake Tana. (D) Fe XRF counts in core MS27PT, Nile delta margin29. (E) Smectite/(chlorite + illite) ratios in core Geo Tü SL110, Nile plume, eastern Mediterranean30. (F) Lake Malawi18. Solid bars indicate high lake levels (C), and high Nile discharge (D,E). Approximate positions of Heinrich events (H1–H6) and P-reflectors (P1–P5) shown. Figure generated in Adobe Illustrator CS6 Version:16.0.4. https://www.adobe.com/uk/.

The 100 kyr record of river discharge at the Nile delta30 shows similarities with effective moisture variation at Lake Tana, in the Nile’s principal headwaters. Nile discharge at the delta was high from >100 to 70 ka, interrupted by a dry episode at ~92 to 88 ka. Wet conditions at Lake Tana are apparent over a similar interval (~132–70 ka), but Tana’s dry episode appears to have been longer (~94–82 ka). After 70 ka, Nile discharge was generally lower than before, with two muted ‘pluvials’29 at ~60–50 ka and 38-30 ka. Tana also shows mostly low lake levels over this period; overspill from the lake occurred at ~54 ka and at ~42 ka, and the seismic data at 42–31 ka indicate higher lake levels; these may be linked to the delta’s ‘pluvials’. Core Geo Tü SL110 from the Nile plume in the eastern Mediterranean32 also shows enhanced Nile discharge during MIS 5; the abrupt increase at 132 kyr coincides with the sharp rise in the level of Lake Tana. The erosion events in Lake Tana (indicated by reflectors P4 and P3; Supplementary Table 3) occur at the end of humid intervals defined in the Nile plume record. However, Heinrich events H6–H2, marked by low Nile discharge, are not clearly apparent in the Tana record; their dates fall in a part of the record where there are many reflectors.

Glacial-age instability at Tana may be explained by diminishing eccentricity and lower precessional amplitude, with high-latitude influences increasing as ice volumes expanded. The variability of high-latitude glacial climate was apparently propagated to Tana, as shown by the frequent lake-level changes in this interval. The mechanism for this tele-connection probably involved a weaker thermohaline circulation during high-latitude stadials leading to reduced heat transport from the tropics and consequent warming of the low-latitude Atlantic, causing drought via diminished monsoon strength as the ocean-continent temperature-pressure gradient diminished. While there is a general correspondence between dry intervals in the Tana record, and ‘cold’ marine isotope stages (Fig. 4), there is less concordance with North Atlantic Heinrich and Greenland Stadials.

Where Lake Tana shows a relatively stable moist climate during MIS 5e–5c, the corresponding period at Lake Malawi (135–90 ka) is marked by two intervals when lake level fell by ~500 m, coinciding with insolation minima at this latitude19. Both lakes record climatic change at the start of MIS 5e, but in opposite directions: Malawi fell to 550 m below the modern level at ~135 ka, whereas Tana rose to overflow at ~132 ka. Similarly, the lakes behaved in opposite directions in MIS 5b: the level of Tana fell, while that of Malawi rose. A revised chronology for Malawi lake-level history also shows low lake level for this interval, but with less detail34. The contrasting but approximately coincident behaviour of the lakes can be attributed to the opposing pattern of precessional forcing in the northern and southern hemispheres: peak insolation values at 12°N coincide with minima at 12°S, their amplitude enhanced by high orbital eccentricity during MIS 5. Both records change character from late MIS 5, but again in opposite directions: Malawi shifts to wetter, more stable conditions from ~70 ka, whereas Tana shows unstable, predominantly arid conditions since ~95 ka.

Implications for modern human dispersal

The shift to wetter conditions at ~70 ka in lakes Malawi, Tanganyika (~97.3 ka) and Bosumtwi (77.9 ka)19 has been linked to the expansion of early modern humans within and out of Africa. Some authors35 attribute population expansion and major behavioural advance within Africa between 80 and 60 ka, with subsequent dispersal to Asia, to selective pressures from varying climate at the MIS 5 - MIS 4 transition, regarding the earlier presence of modern humans in the Levant as short-lived. However, molecular data provide a wide range of dates, ~144 ka to 30 ka, for human expansion and dispersal36.

One model of human evolutionary response to climate variability37 indicates that a period of stable climate following an abrupt transition from relatively unstable conditions would favour the expansion of refugial AMH populations with the capacity to exploit marginal environments through behavioural versatility. Using similar quantitative criteria (see Supplementary Methods) we identified four stable wet intervals from the Ca/ Ti record of Lake Tana (Supplementary Fig. 18): >150–144 ka (MIS 6), 125–93 ka (MIS 5e–5c), 82-73 ka (MIS 5a), and 42–34ka (MIS 3) closely resembling simulated human dispersal intervals38. The longest of these, MIS 5e–5c, was preceded by an abrupt transition from variable climate in late MIS 6 that could have provided the selective pressure for versatility, and then presented long-lasting, relatively stable, moist, resource-rich conditions conducive to the demographic increase and range expansion of innovative populations into a wide range of habitats, including the Levant and Arabia21. The long (32 ka) duration of this interval could have allowed multiple dispersal events39. A similar abrupt transition at ~82 ka, from the most severe arid episode recorded to a shorter interval of stable wet conditions in MIS 5a may again have promoted population expansion and dispersal. Subsequent relatively brief wet phases at ~62 ka, ~55 ka and ~40 ka may have favoured further expansions40.

The early, multiple dispersal model supported here dispenses with the anomalously long time gap between modern human emergence and behavioural, technological advances in southern Africa that could have driven demographic expansion within Africa at ~80–60 ka, with subsequent dispersal into Asia35. The contrast between favourable interglacial conditions at Tana and contemporaneous mega-droughts at Malawi supports the view that north-eastern rather than southern Africa was the principal region of AMH increase and dispersal. Lake Tana, despite its shallow depth, shows little evidence of complete and prolonged desiccation during the ensuing glacial, suggesting that human populations could have survived in highland refugia. Overall, the Tana record shows interglacial conditions favourable for AMH increase and dispersal during the time windows suggested by recent palaeontological, archaeological and genetic data, close to likely dispersal routes into SW Asia.

Methods

Cores 07TL-1 (10-810 cm below sediment surface), PT07-1 (2289–4202 cm bss) and PT07-2 (1315–9180 cm bss) were drilled in close proximity in January 2007 at E37° 19′ 24.3″, N12°11′56.3″, 2 km SSW of the port of Gorgora on Lake Tana’s north shore. Archive sections of the cores were scanned with an Itrax® XRF core scanner at 2 mm intervals, using a Mo X-ray tube operating at 30 kV, 50 mA with 10 second exposure times (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Fig. 4). In the absence of terrestrial macrofossils, bulk sediment was used for radiocarbon analysis (Supplementary Methods). Results are reported as % modern 14C and 14C years BP (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 1). Samples were prepared for luminescence dating according to standard methods for polymineral fine-grains (i.e. 4–11 μm diameter grains) as described in41. A post-IR infrared stimulated luminescence (pIRIRSL)42 protocol was used for dating the sediments, similar to that of 43. The luminescence ages (ka) (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 2) were determined using the pIRIR225 signal calculated using the dose rates (Gy/ka) and the equivalent dose (Gy) values also shown in the table. These 15 pIRIR225 ages, plus four calibrated radiocarbon ages (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 1), were combined to give the age-depth model (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Fig. 5) constructed using the R-software package Bchron v. 4.1.1.

Seismic survey around the core site was undertaken using an IKB- SEISTECTM boomer operated at 105 Joules, providing a vertical resolution of 5–10 cm in the uppermost 10 m of sediments, reducing to around 50 cm at maximum penetration depth (c. 170 m). Ages were assigned to reflectors by converting the seismic two-way-travel times (TWT) of the reflectors to depths, and then converting the depths to ages using the age-depth model for the core. Detail of these procedures and the seismic results are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by grants from the UK Natural Environmental Research Council (NERC; grant nos NER/B/S/2002/00540 and NE/DO12996/1) and NERC Radiocarbon Facility support (NRCF010001 allocation number 1201.1006). We thank members of the Department of Earth Sciences at Addis Ababa University for scientific and logistical support, especially the late Mohammed Umer; Addis Zeleke of Addis Geosystems plc; and the Amhara Region Agricultural Research Institute. Data are archived at the UK National Geoscience Data Centre, http://www.bgs.ac.uk/services/ngdc/home.html.

Author Contributions

H.F.L., C.R.B., S.J.D., and D.H. planned the project and undertook fieldwork in Ethiopia. M.H.M. undertook fieldwork and carried out XRF scans and laboratory analyses. H.M.R. determined luminescence dates and constructed the age model; C.B. carried out radiocarbon analyses. H.T. assisted with fieldwork and in the laboratory. All authors discussed the results and interpretation. H.F.L. wrote the manuscript with input from C.R.B., S.J.D., D.H. and H.M.R.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are deposited at the UK National Geoscience Data Centre (http://www.bgs.ac.uk/services/ngdc/).

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

12/17/2018

A correction to this article has been published and is linked from the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has been fixed in the paper.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-19601-w.

References

- 1.White TD, et al. Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia. Nature. 2003;423:742–747. doi: 10.1038/nature01669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aubert M, et al. Confirmation of a late middle Pleistocene age for the Omo Kibish 1 cranium by direct uranium-series dating. J Hum Evol. 2012;63:704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hublin JJ, et al. New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens. Nature. 2017;546:289–292. doi: 10.1038/nature22336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu Q, et al. A revised timescale for human evolution based on ancient mitochondrial genomes. Curr Biol. 2013;23:553–559. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scozzari R, et al. An unbiased resource of novel SNP markers provides a new chronology for the human Y chromosome and reveals a deep phylogenetic structure in Africa. Genome Research. 2014;24:353–344. doi: 10.1101/gr.160788.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groucutt HS, et al. Rethinking the Dispersal of Homo sapiens out of Africa. Evol Anthropol. 2015;24:149–164. doi: 10.1002/evan.21455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groucutt HS, et al. Stone tool assemblages and models for the dispersal of Homo sapiens out of Africa. Quaternary International. 2015;382:8–30. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2015.01.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stringer C. The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens. Philos T R Soc B. 2016;371:20150237. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grun R, et al. U-series and ESR analyses of bones and teeth relating to the human burials from Skhul. Journal of Human Evolution. 2005;49:316–334. doi: 10.1016/jjhevol.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu W, et al. The earliest unequivocally modern humans in southern China. Nature. 2015;526:696–699. doi: 10.1038/nature15696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westaway KE, et al. An early modern human presence in Sumatra 73,000-63,000 years ago. Nature. 2017;548:322–325. doi: 10.1038/nature23452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demeter F, et al. Anatomically modern human in Southeast Asia (Laos) by 46 ka. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:14375–14380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208104109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunz P, et al. Early modern human diversity suggests subdivided population structure and a complex out-of-Africa scenario. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6094–6098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808160106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armitage SJ, et al. The southern route “out of Africa”: evidence for an early expansion of modern humans into Arabia. Science. 2011;331:453–456. doi: 10.1126/science.1199113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malaspinas AS, et al. A genomic history of Aboriginal Australia. Nature. 2016;538:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature18299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mallick S, et al. The Simons Genome Diversity Project: 300 genomes from 142 diverse populations. Nature. 2016;538:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature18964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarkson C, et al. Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago. Nature. 2017;547:306–310. doi: 10.1038/nature22968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pagani L, et al. Genomic analyses inform on migration events during the peopling of Eurasia. Nature. 2016;538:238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature19792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scholz CA, et al. East African megadroughts between 135 and 75 thousand years ago and bearing on early-modern human origins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16416–16421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703874104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larrasoana JC, Roberts AP, Rohling EJ. Dynamics of green Sahara periods and their role in hominin evolution. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breeze P, et al. Palaeohydrological corridors for hominin dispersals in the Middle East∼ 250–70,000 years ago. Quat Sci Rev. 2016;144:155–185. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boivin N, Fuller DQ, Dennell R, Allaby R, Petraglia MD. Human dispersal across diverse environments of Asia during the Upper Pleistocene. Quaternary International. 2013;300:32–47. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2013.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costa K, Russell J, Konecky B, Lamb H. Isotopic reconstruction of the African Humid Period and Congo Air Boundary migration at Lake Tana, Ethiopia. Quaternary Science Reviews. 2014;83:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.10.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prave AR, et al. Geology and geochronology of the Tana Basin, Ethiopia: LIP volcanism, super eruptions and Eocene–Oligocene environmental change. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2016;443:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2016.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams M, et al. Abrupt return of the summer monsoon 15,000 years ago: new supporting evidence from the lower White Nile valley and Lake Albert. Quaternary Science Reviews. 2006;25:2651–2665. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lamb HF, et al. Late Pleistocene desiccation of Lake Tana, source of the Blue Nile. Quaternary Science Reviews. 2007;26:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.11.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marshall MH, et al. Late Pleistocene and Holocene drought events at Lake Tana, the source of the Blue Nile. Global and Planetary Change. 2011;78:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2011.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stager JC, Ryves DB, Chase BM, Pausata FS. Catastrophic drought in the Afro-Asian monsoon region during Heinrich event 1. Science. 2011;331:1299–1302. doi: 10.1126/science.1198322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies, S. J., Lamb, H. F. & Roberts, S. J. In Micro-XRF Studies of Sediment Cores Developments in Paleoenvironmental Research (ed R. G. Rothwell I. W. Croudace) (Springer, 2015).

- 30.Weldeab S, Lea DW, Schneider RR, Andersen N. 155,000 years of West African monsoon and ocean thermal evolution. Science. 2007;316:1303–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1140461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Revel M, et al. 100,000 Years of African monsoon variability recorded in sediments of the Nile margin. Quaternary Science Reviews. 2010;29:1342–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehrmann W, Schmiedl G, Seidel M, Kruger S, Schulz H. A distal 140 kyr sediment record of Nile discharge and East African monsoon variability. Climate of the Past. 2016;12:713–727. doi: 10.5194/cp-12-713-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tierney JE, demenocal PB, Zander PD. A climatic context for the out-of- Africa migration. Geology. 2017;45:1023–1026. doi: 10.1130/G39457.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ivory SJ, et al. Environmental change explains cichlid adaptive radiation at Lake Malawi over the past 1.2 million years. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:11895–11900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611028113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mellars P. Why did modern human populations disperse from Africa ca. 60,000 years ago? A new model. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9381–9386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510792103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reyes-Centeno H, Hubbe M, Hanihara T, Stringer C, Harvati K. Testing modern human out-of-Africa dispersal models and implications for modern human origins. J Hum Evol. 2015;87:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grove M, et al. Climatic variability, plasticity, and dispersal: a case study from Lake Tana, Ethiopia. J Hum Evol. 2015;87:32–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timmermann A, Friedrich T. Late Pleistocene climate drivers of early human migration. Nature. 2016;538:92–95. doi: 10.1038/nature19365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tassi F, et al. Early modern human dispersal fromAfrica: genomic evidence for multiple waves of migration. Investig Genet. 2015;6:13. doi: 10.1186/s13323-015-0030-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jennings, R. et al. Human occupation of the northern Arabian interior during early Marine Isotope Stage 3. J Quat Sci 31.8 953–966, 10.1002/jqs.2920 (2016)

- 41.Roberts HM. Testing Post-IR IRSL protocols for minimising fading in feldspars, using Alaskan loess with independent chronological control. Radiat Meas. 2012;47:716–724. doi: 10.1016/j.radmeas.2012.03.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomsen KJ, Murray AS, Jain M, Botter-Jensen L. Laboratory fading rates of various luminescence signals from feldspar-rich sediment extracts. Radiat Meas. 2008;43:1474–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.radmeas.2008.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buylaert JP, Murray AS, Thomsen KJ, Jain M. Testing the potential of an elevated temperature IRSL signal from K-feldspar. Radiat Meas. 2009;44:560–565. doi: 10.1016/j.radmeas.2009.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are deposited at the UK National Geoscience Data Centre (http://www.bgs.ac.uk/services/ngdc/).