Abstract

Gating of the mammalian inward rectifier Kir1.1 at the helix bundle crossing (HBC) by intracellular pH is believed to be mediated by conformational changes in the C-terminal domain (CTD). However, the exact motion of the CTD during Kir gating remains controversial. Crystal structures and single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer of KirBac channels have implied a rigid body rotation and/or a contraction of the CTD as possible triggers for opening of the HBC gate. In our study, we used lanthanide-based resonance energy transfer on single-Cys dimeric constructs of the mammalian renal inward rectifier, Kir1.1b, incorporated into anionic liposomes plus PIP2, to determine unambiguous, state-dependent distances between paired Cys residues on diagonally opposite subunits. Functionality and pH dependence of our proteoliposome channels were verified in separate electrophysiological experiments. The lanthanide-based resonance energy transfer distances measured in closed (pH 6) and open (pH 8) conditions indicated neither expansion nor contraction of the CTD during gating, whereas the HBC gate widened by 8.8 ± 4 Å, from 6.3 ± 2 to 15.1 ± 6 Å, during opening. These results are consistent with a Kir gating model in which rigid body rotation of the large CTD around the permeation axis is correlated with opening of the HBC hydrophobic gate, allowing permeation of a 7 Å hydrated K ion.

Introduction

The Kir1.1 family of inward rectifier K channels (encoded by the KCNJ1 gene) is found primarily at the apical membrane of the renal thick ascending limb, distal tubule, connecting tubule, and cortical collecting duct. The three isoforms, Kir1.1a, Kir1.1b, and Kir1.1c (often referred to as ROMK for renal outer medullary K) have similar function but somewhat different distribution along the mammalian nephron (1). Although Kir1.1 is an inward rectifier, it nonetheless carries significant outward current, enabling it to both secrete K and recycle it in the thick ascending limb, thereby facilitating the NKCC2 triple cotransporter that accounts for 25% of Na absorption in the nephron. Renal Kir1.1 channels are generally open under physiological conditions, provided specific PKA sites on the channel are phosphorylated (2). However, intracellular acidification or dephosphorylation completely blocks K permeation (2, 3, 4).

The main gate of Kir1.1 is believed to reside at the helix bundle crossing (HBC), which is thought to constrict during channel closure (5, 6), but this is not necessarily the case for other K channels such as MthK (7, 8) or BK (9). Consequently, an experimental determination of HBC motion during inward rectifier gating would help clarify important similarities or differences among K channels. Furthermore, the mechanics of gate closure and its link to the C-terminal domain (CTD) are also controversial. Details of the gating process have begun to emerge from x-ray diffraction studies of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic Kir crystals (10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). However, most of these studies provide information only about the closed (or minimum energy) state of the channel. Much less is known about the open-state conformation or the role of the CTD in the gating process.

Nonetheless, several x-ray diffraction studies have provided snapshots of the open-state and fostered models of the inward rectifier gating process. Crystallization of a bacterial, constitutively open mutant, S129R-KirBac3.1, implied that a 23° rigid body rotation of the CTD around the permeation axis opens the HBC gate in an iris-like fashion (10). Further evidence for the role of the CTD in Kir gating comes from x-ray diffraction of GIRK2, in which the HBC opening was initiated by a 4° rotation of the CTD, followed by additional twisting and widening of the HBC to allow passage of a hydrated K ion (15). In another study, a PIP2-induced translocation of the CTD toward the membrane produced a preopen state of the Kir2 channel (12).

Despite general agreement that the HBC constitutes the primary gate of inward rectifier channels, the role of the CTD in Kir gating is not well understood. For example, closure of GIRK (Kir3.x) channels was associated with C-terminal rotation and an increase in the distance between N- and C-termini (16). This was opposite to a decrease in the N- to C-terminal distance, reported with patch-clamp fluorometry (17).

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements with prokaryotic KirBac1.1 implied that channel closure is accompanied by bending of the inner helices and narrowing of the CTD cytoplasmic pore (18). However, single-molecule FRET (also on KirBac1.1) indicated that HBC closure was associated with a twisting and widening of the CTD (19). Moreover, solution-based, single-molecule FRET on KirBac1.1 in lipid nanodisks indicated that HBC closure was correlated with CTD widening at a site close to the HBC (R151C-KirBac1.1), but CTD narrowing at another site (G249C-KirBac1.1) farther from the HBC (20).

Given the controversy regarding the link between the CTD and the inward rectifier HBC gate, we used lanthanide-based resonance energy transfer (LRET) to address conformational changes in both the CTD and the HBC during Kir1.1 gating. To minimize ambiguity in Förster energy transfer, single-Cys dimers of Kir1.1b were constructed using the method pioneered in (21). The dimers were produced in a cell-free (CF) wheat-germ system (WEPRO 2240), suitable for translation of mammalian integral membrane proteins (22), and functionality was verified by direct injection of CF proteoliposomes into Xenopus oocytes (23, 24). An important advantage of our experimental approach is that it combines the established techniques of 1) CF translation, 2) single-Cys dimer construction, 3) direct injection of proteoliposomes into oocytes, and 4) LRET lifetime measurements, to obtain structural information about inward rectifier gating.

Methods

Förster energy transfer with single-Cys dimers

We investigated state-dependent conformational changes in the mammalian renal inward rectifier Kir1.1b (ROMK2) using LRET, a variant of fluorescence energy transfer, in which lanthanide donors (e.g., Tb3+ maleimide) transfer energy upon excitation to a sensitized fluorophore acceptor. After removal of native accessible cysteines in Kir1.1b, single cysteines were reintroduced into dimeric constructs of Kir1.1b that subsequently self-assemble as functional tetrameric channels in liposome membranes. C-terminal width was calculated from Förster energy transfer between labeled single-Cys dimers (C189-Kir1.1b and C289-Kir1.1b) on diagonally opposite subunits in the CTD. In addition, the dimensions of the HBC gate (L160-Kir1.1b) were determined from energy transfer between diagonal C161 residues, in which a native Ala had been replaced with a Cys (A161C-Kir1.1b).

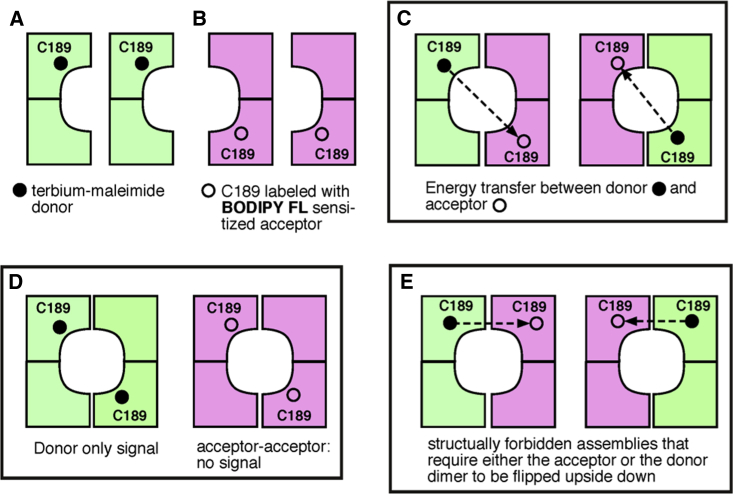

The LRET labeling strategy is illustrated in Fig. 1 for the case of C189-Kir1.1b. In this example, single-Cys dimers were simultaneously labeled with Tb chelate donor (Fig. 1 A) and BODIPY-FL maleimide acceptor (Fig. 1 B). About 50% of the resulting tetrameric channels would transfer energy between C189 residues on opposite subunits, and thereby provide an unambiguous measurement of CTD width (Fig. 1 C). Another 25% of the channels would have only donors, providing a Tb-only time constant (Fig. 1 D), and the remaining 25% of the channels would have only acceptors and contribute no signal (Fig. 1 D). Energy transfer would never occur between donors and acceptors on adjacent subunits (Fig. 1 E) because this would require the dimers to be oriented in opposite directions with the selectivity filter of one dimer adjacent to the C-terminus of the other.

Figure 1.

Possible tetrameric configurations during labeling of C189-Kir1.1b, single-Cys dimers. (A) Dimers labeled with terbium chelate donor, (B) dimers labeled with BODIPY-FL maleimide SE. Upon mixing, dimers (A and B) self-assemble into tetramers having one donor and one acceptor ((C) ∼50%), or tetramers having only donors or only acceptors ((D) ∼25% each). Donors and acceptors on adjacent subunits (E) are not structurally possible. To see this figure in color, go online.

The C289 and A161C single-Cys dimers were constructed and labeled by a protocol similar to Fig. 1. Since different molecular distances require different donor and acceptor labels for optimal energy transfer, we chose a Tb-BODIPY-FL-labeled pair (R0 = 42.7 Å) for C189 and C289, and a Tb-Atto465-labeled pair (R0 = 21–26 Å) for A161C, based on homology model dimensions, where R0 is the distance for half-maximal energy transfer. Further details of the labeling process are given in the Supporting Material.

LRET determination of molecular distances

Both LRET and FRET utilize the principles of Förster energy transfer to determine intramolecular distances. However, LRET offers certain advantages over conventional FRET measurements. First, the unpolarized emission and millisecond lifetime of lanthanides (versus nanosecond for FRET) produce less ambiguity in the orientation factor for LRET (κ2 = 2/3) compared with FRET. Second, lanthanides have highly spiked emission spectra as well as significant overlap with acceptor dyes that bind readily to biological proteins. The spiked spectra of a lanthanide donor like terbium (Tb3+) allows clear separation between Tb donor emission and acceptor sensitized emission. Third, the long luminescence lifetime of lanthanide donors allows delayed collection of the sensitized emission signal, thereby avoiding interference from direct excitation of the acceptor label. Finally, use of LRET donor and acceptor lifetime ratios, rather than absolute FRET energies, permits high-sensitivity structural determinations from a small batch of proteins that have not been exhaustively purified.

In our experiments, molecular distance information (r) was extracted from the energy transfer (E) between labeled cysteines on opposite subunits, as determined by the ratio of sensitized acceptor lifetime (τSE) to donor-only lifetime (τDO) according to

| (1) |

The distance (r) between donor and acceptor labels is related to the Förster energy transfer according to

| (2) |

where R0 (the distance for half-maximal energy transfer) was calculated from first principles (25, 26), as outlined in the Supporting Material. The above equations are a modification of Förster Energy theory (25), which allows distance determinations from donor and sensitized acceptor lifetimes (26).

In practice, luminescence decay was recorded as a function of time, and the biexponential lifetime decay functions were fit to the data according to

| (3) |

where A is the amplitude factors and tau (τ) is the decay time constants. Since excitation of the Tb maleimide chelate produced both fast (f) and slow (s) donor states (27), two sensitized acceptor time constants (τSE) were determined for each Tb3+ donor state. The resulting donor-only (DO) and sensitized acceptor (SE) time constants were used to calculate intramolecular Cys-Cys distances (Eqs. 1 and 2) for both closed (pH 6) and open (pH 8) conditions. Further details of these calculations are described in the Supporting Material.

CF production and labeling of single-Cys dimers

C189, C289, and A161C single-Cys Kir1.1b dimeric constructs were prepared by linking monomeric single-Cys subunits to Cys-free subunits, formed by replacing the six normally occurring Cys of Kir1.1b as follows: C30V, C156S, C189T, C289V, C336A, and C339A. The single-Cys and the Cys-free inserts were linked together with five amino acids (QQQQS), analogous to the method developed in (21). In addition, a Cys-free monomer was also produced to test the level of background labeling. Finally, the two inaccessible Kir1.1b cysteines that form a disulfide linkage between C132 and C104 were left unchanged in all constructs because they stabilize proper folding of the channel and are not accessible to external labeling.

The single-Cys dimeric open-reading frame was subcloned into a pEU plasmid and used for in vitro transcription of RNA, which directed protein synthesis in a wheat-germ CF dialysis translation system (WEPRO 2240; CFS, Yokohama, Japan), supplemented with extruded POPE plus POPG liposomes (23, 24). During the translation reaction, C189, C289, or A161C protein is incorporated into anionic (POPE plus POPG) liposomes that have been added to the reaction mixture. After 23 h incubation at 23°C, the CF reaction product was centrifuged (18,000 × g for 3 min) and the pellet was washed. The resulting pellet was either resuspended in 158 mM 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (KMOPS) buffer and injected into oocytes to evaluate function, or solubilized in 35 mM 3-((3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio)-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) plus 158 mM KMOPS buffer for labeling and LRET.

In the LRET experiments, single-Cys dimers were simultaneously labeled with terbium chelate and either BODIPY-FL maleimide (C189, C289) or Atto465 maleimide (A161C), followed by desalting to remove any excess label material, and a 2 h incubation period (21°C) with POPE (75%), POPG (23%), and PIP2 (2%) in 35 mM CHAPS plus 158 mM KMOPS. Final LRET proteoliposomes were formed by removal of CHAPS using partially dehydrated G50 columns at either pH 6 or 8 (28). Since the channel orientation in the final proteoliposomes is unknown, this protocol guarantees that all channels in the pH 6 sample will be exposed to pH 6 on both sides, and all channels in the pH 8 sample will be exposed to pH 8 on both sides. Kir1.1 is gated only by internal pH and is unaffected by extracellular pH (pHo), as determined in separate experiments with impermeant external buffers. Further details of the labeling protocol are given in the Supporting Material.

Oocyte functional assay for Kir1.1b proteoliposomes

Functionality of the CF constructs was assessed by direct injection of C189, C289, or A161C proteoliposomes into Xenopus oocytes, and subsequent recording of single-channel or whole-cell currents (23, 24). Proteoliposome suspensions for oocyte injection were prepared by centrifuging the CF reaction product, washing the resulting CF pellet in buffer (vol = 0.6 × translation vol) containing 25 mM HEPES and 100 mM KCl (pH 7.5), and resuspending in 1:20 volume of the original translation mixture. Before injection, the proteoliposomes were treated with 0.01 mg/mL RNase A to eliminate any residual RNA, followed by a second wash to eliminate the added RNase.

Each collagenase-treated, stage 4 Xenopus oocyte (Ecocyte Biosciences, Austin, TX) was injected with 46 nL of the proteoliposome suspension using a Drummond microinjector (Drummond Co., Broomall, PA). The underlying presumption of this methodology is that incorporation of dimeric constructs into liposomes results in self-assembled tetrameric channels that are trafficked to the oocyte surface, where they exhibit the characteristics of functional channels (23, 24). Although there is ample evidence that injected channel protein is indeed trafficked to the oocyte membrane (23), we do not yet understand the details of this process.

Cell-attached patch-clamp recordings or two-electrode voltage clamp recordings were obtained from proteoliposome-injected oocytes using standard electrophysiological methods, as previously reported (5, 23, 24, 29). Oocyte internal pH was controlled with permeant acetate buffers, according to a prior calibration between intracellular pH (pHi) and pHo obtained with ion-selective microelectrodes: pHi = 0.595 × pHo + 2.4 (3). The pHo (6 ≤ pHo ≤ 9) used to control pHi has no direct effect on channel function.

Optical LRET measurements on Kir proteoliposomes

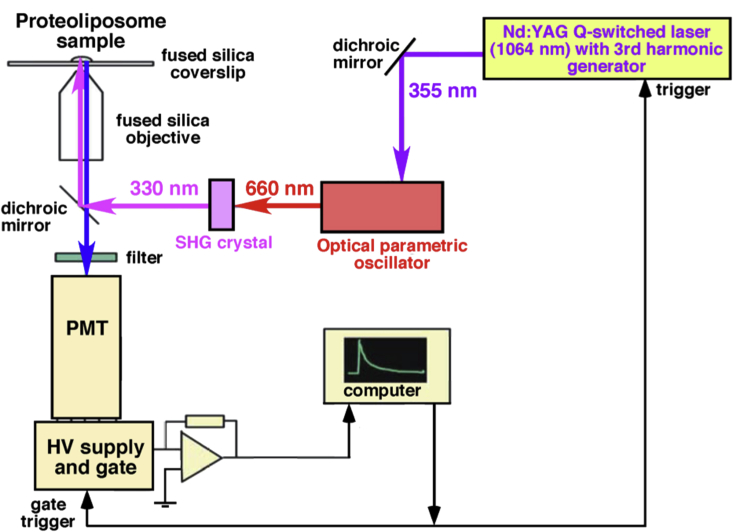

Lifetime decay time constants for the terbium donor τDO and SE τSE, required for Eqs. 1 and 2, were obtained from a custom-designed LRET acquisition system, using an INDI Nd:YAG Q-switched laser (Spectra-Physics) in series, with an optical parametric oscillator (λ = 660 nm) and second harmonic generator crystal to produce a Tb excitation wavelength of 330 nm (Fig. 2). This excitation signal was directed at labeled Kir1.1b proteoliposomes, resting on a fused silica coverslip (Esco Products, Oak Ridge, NJ).

Figure 2.

Optical setup for LRET measurements from Kir1.1b proteoliposomes, resting on a fused silica coverslip in a controlled pH solution. The data acquisition photomultiplier is gated to open 50 μs after the laser pulse, to avoid saturation by the 330-nm excitation signal. To see this figure in color, go online.

DO and SE signals were collected via a 40× glycerol immersion quartz objective (Partec, Münster, Germany), filtered with long pass or band pass filters (488/10, 520/25, and 567/15 nm), and detected by a high gain photomultiplier (Prod for Research Inc, Danvers, MA) gated to open 50 μs after the 330-nm excitation (Fig. 2).

Data were collected as averages of 50 pulses, spaced 500 ms apart. The photomultiplier electrical output was filtered with an eight-pole Bessel filter at a corner frequency of either 100 or 500 kHz, and acquired with a sample period of 1 μs, using a 16-bit analog-to-digital converter (Measurement Computing), as previously reported (30). Since Kir1.1b is gated by pH rather than voltage, it is ideally suited for state-dependent LRET measurements in open-circuited (Vm = 0) proteoliposomes maintained at different pHs.

Homology modeling

Our closed-state homology model for Kir1.1b (ROMK2) was based on the closed x-ray crystal structure of the chicken Kir2.2 (13), and our open-state model was based on the open model developed in (31). Model building and refinement were carried out using the CHARMM molecular modeling program (32) and the CHARMM Param22 force field (33).

In both the open- and closed-state models, each C161-Kir1.1b residue is 3.75 Å farther out from the central axis of the channel than the edge of the HBC hydrophobic gate at L160-Kir1.1b (5). Consequently, the diagonal width of the HBC gate will always be 7.5 Å (2 × 3.75 Å) smaller than the measured C161-C161 distance between diagonally opposite subunits.

Results

Functionality of the single-Cys constructs

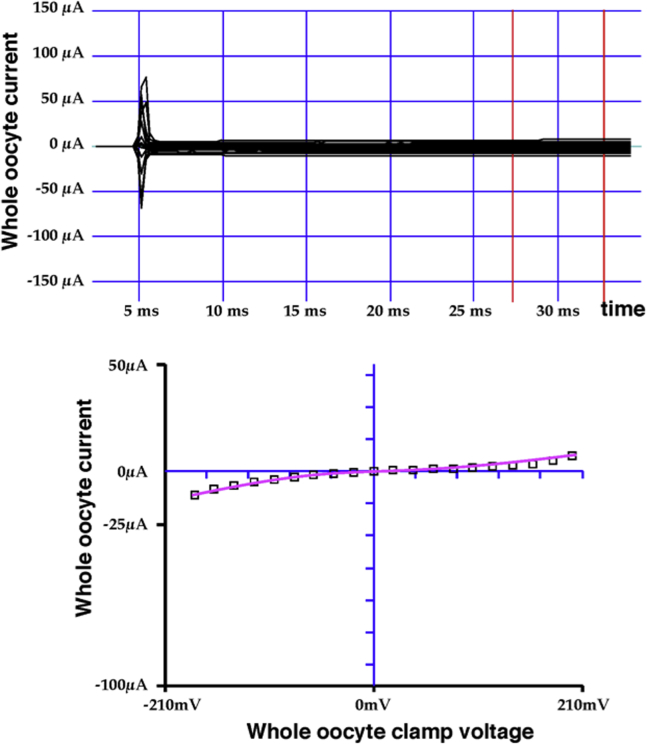

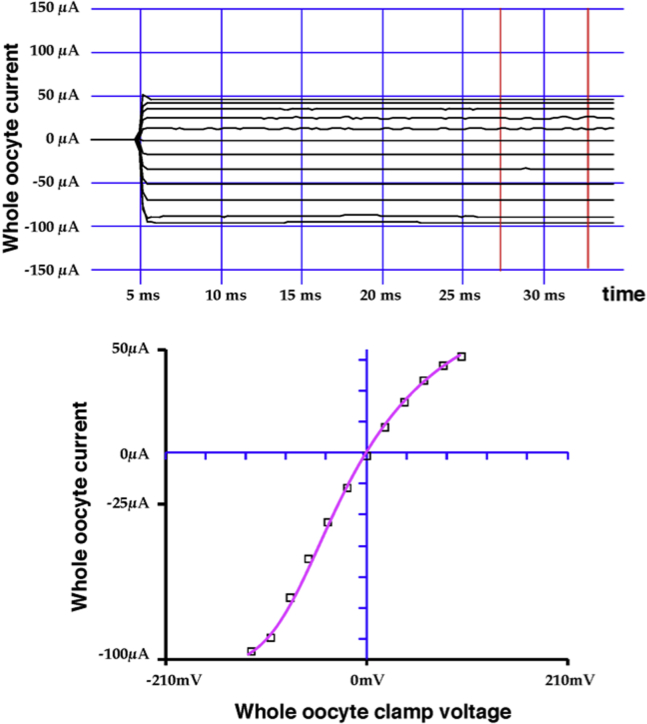

Functionality of C189-Kir1.1b channels was evaluated in Xenopus oocytes 24 h after direct injection of C189 proteoliposomes (24). In these experiments, patch-clamp recordings demonstrated K channels with an average inward conductance (gK) of 36 pS and open probability (Po) of 0.8 (24). In our study, C289 and A161C function was assessed with two-electrode voltage clamp whole-cell recordings on intact oocytes. An example is illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4 for A161C-Kir1.1b in 100 mM K acetate solutions. The presumption is that internal oocyte K is ∼100 mM (although this was not measured in these experiments). At internal pH 6, A161C-Kir1.1b oocytes showed very little inward or outward current, consistent with oocytes having mostly closed channels (Fig. 3). At internal pH 8 (controlled with permeant acetate buffers), inward and outward K current increased in a manner consistent with pH-dependent gating of a weak inward rectifier (Fig. 4). Whole-cell conductance was pH dependent even at zero membrane potential (Figs. 3 and 4), which corresponds to the open-circuit condition of the LRET experiments. In separate patch-clamp experiments, we confirmed that A161C-Kir1.1b single channels were also strongly gated by cytoplasmic side pH.

Figure 3.

Current-voltage data for an A161C-Kir1.1b oocyte at internal pH 6, controlled with a 100 mM K acetate buffer. Whole-cell oocyte currents were recorded with a two-electrode voltage clamp. Conductance (slope) at 0 mV clamp potential indicates a predominance of closed channels at pH 6. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 4.

Current-voltage data for the same A161C-Kir1.1b oocyte as in Fig 3, but with internal pH 8, controlled with a 100 mM K acetate buffer. Conductance (slope) at 0 mV clamp potential indicates a predominance of open channels at pH 8. To see this figure in color, go online.

pH sensitivity of the Cys mutants

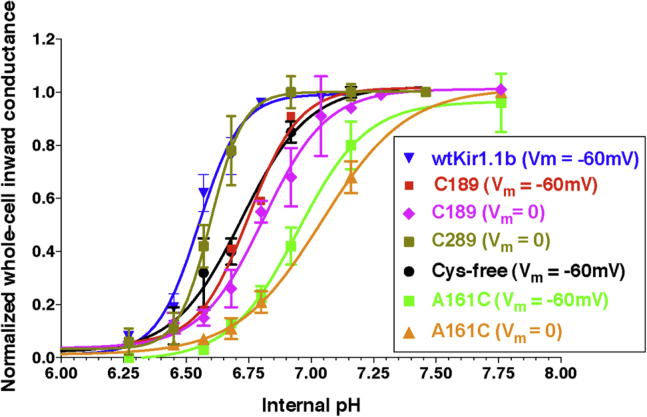

Since it was not possible to measure physiological function during the LRET measurements, the pH sensitivity of single-Cys dimer channels was confirmed in separate oocyte experiments, similar to those of Figs. 3 and 4. Although the family of Cys mutants showed some pKa variability, they were all gated by internal pH similar to wild-type Kir1.1b (Fig. 5). Consequently, LRET experiments on C189, C289, and A161C at pH 6 and pH 8 should accurately reflect the closed and open states of Kir1.1b, respectively.

Figure 5.

pH dependence of wild-type Kir1.1b and cysteine mutants. Whole-cell inward conductance measured with two-electrode voltage clamp in oocytes at the indicated membrane potentials. To see this figure in color, go online.

CTD dimensions at C189-Kir1.1b

C189-Kir1.1b proteoliposome channels, containing both a single donor and a single acceptor, exhibited luminescence lifetime decays at pH 6 and pH 8, corresponding to closed and open states, respectively (Fig. 6). DO and SE time constants, determined from the data of Fig. 6, are summarized in Table 1, where Tb maleimide exhibits both fast and slow donor states (27). Distances between C189 residues on opposite diagonal subunits were calculated from DO and SE time constants using Eqs. 1 and 2 and the half-maximal energy transfer distances for the donor-acceptor pair (Table 1). Combining the r values for the two Tb donor states, the average diagonal distance between opposite C189s was 33.2 ± 6 Å in the (pH 6) closed state and 34.2 ± 6 Å in the (pH 8) open state (Table 1).

Figure 6.

Normalized LRET lifetimes for C189-Kir1.1b dimer proteoliposomes in 158 mM KMOPS. (A) Closed state at pH 6. (B) Open state at pH 8. C189 dimers were labeled with Tb chelate donor and BODIPY-FL acceptor. Black tracings denote Tb donor-only (DO) signal, fitted with fast and slow Tb time constants (red lines). Green tracings are the corresponding sensitized acceptor (SE) lifetimes at (A) pH 6 (closed state) and (B) pH 8 (open state), together with exponential fits (red lines). Time constants are listed in Table 1, and additional calculations are in Supporting Material. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 1.

LRET Lifetime Decays and Calculated C189-Kir1.1b Distances between Diagonally Opposite Subunits in the CTD

|

Data were obtained from energy transfer between Tb donors and BODIPY-FL acceptors on tetrameric C189-Kir1.1b, self-assembled in proteoliposomes from single-Cys Cl89 dimers. τ denotes lifetime decay constants for donors and acceptor sensitized emission, f indicates fast donor state, and s indicates slow donor state. R0 is the distance corresponding to 50% energy transfer, and r is the donor acceptor distance at the designated pH. The average distance between diagonal Cl89 residues in the CTD was 33.2 ± 6 Å at pH 6 and 34.2 ± 6 Å at pH 8.

The similarity in the open and closed C189 distances implies that the CTD does not change shape at position 189 during alkaline-induced opening of the HBC gate. As such, the data are consistent with a model in which the CTD rotates around the permeation axis as a rigid body during channel opening, with no change in relative distance between opposite C189 residues.

It should be noted that the absolute LRET (r) distances in Table 1 are somewhat smaller than the C189-C189 distance (39 Å) predicted by our homology model, derived from Kir2.2 (13) and KirBac3.1 (10). This is not too surprising since LRET measures the distance between donor and acceptor labels attached to Cys, rather than the distance between actual Cys residues.

CTD dimensions at C289-Kir1.1b

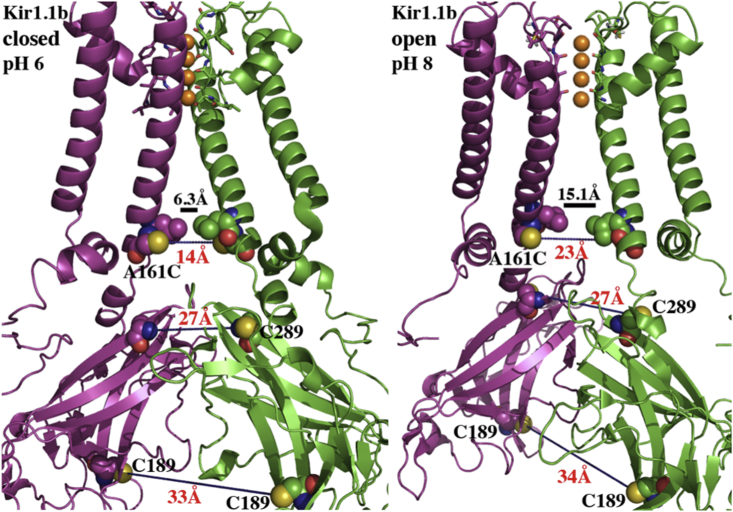

We also determined state-dependent distances at another position (C289-Kir1.1b) in the CTD that is somewhat closer to the HBC than C189 (Fig. 10). LRET lifetimes for both DO and acceptor sensitized emission were similar for the closed state at pH 6 and the open state at pH 8 (Fig. 7). Fits to the lifetime decays of Fig. 7 are summarized in Table 2, together with the calculated distances (r) between C289 residues on opposite diagonal subunits. As with C189, we averaged the distances for fast and slow Tb donor states. This yielded a C289 diagonal distance of: 26.8 ± 3 Å for the closed state (pH 6) and 27.0 ± 4 Å for the open state (pH 8). Again, the similarity in the open and closed state diagonal distances at C289 implies that the CTD does not change shape at this position during alkaline-induced HBC gating. Both values are very close to the 27 Å distance predicted by the homology model for diagonally opposite C289 residues (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

State-dependent Kir1.1b dimensions measured by LRET between paired Cys on opposite subunits. C189: 33 Å (closed) to 34 Å (open). C289: 27 Å (closed) to 27 Å (open). A161C: 14 Å (closed) to 23 Å (open). Solid bar denotes width of actual HBC gate: 6.3 Å (closed, pH 6) and 15.1 Å (open, pH 8), derived from A161C distances. Open and closed state structures were drawn in Pymol from our homology model (Methods).

Figure 7.

Normalized LRET lifetimes for C289-Kir1.1b dimer proteoliposomes in 158 mM KMOPS. (A) Closed state at pH 6. (B) Open state at pH 8. C289 dimers were labeled with Tb chelate donor and BODIPY-FL acceptor. Black tracings denote Tb DO signal, fitted with fast and slow Tb time constants (red lines). Green tracings are the corresponding SE lifetimes at (A) pH 6 (closed state) and (B) pH 8 (open state), together with exponential fits (red lines). Time constants are listed in Table 2, and additional calculations are in Supporting Material. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 2.

LRET Lifetime Decays and Calculated C289-Kir1.1b Distances

|

Data were obtained from energy transfer between Tb donors and BODIPY-FL acceptors on tetrameric C289-Kir1.1b, self-assembled in proteoliposomes from single-Cys C289 dimers. τ denotes lifetime decay constants for donors and acceptor sensitized emission, f indicates fast donor state, and s indicates slow donor state. R0 is the distance corresponding to 50% energy transfer and r is the donor acceptor distance at the designated pH. The average distance between diagonal C289 residues in the CTD was 26.8 ± 3 Å at pH 6 and 27.0 ± 4 Å at pH 8.

In summary, LRET measurements at two separate locations (C189 and C289) in the cytoplasmic domain of Kir1.1b offered no support for a change in CTD width during pH gating of Kir1.1b.

HBC dimensions at A161C-Kir1.1b

The absence of any change in CTD width at either C189 or C289 required a positive control to confirm that our LRET method could resolve a pH-associated change in Kir1.1b conformation. The obvious choice was to use LRET to measure the dimensions of the HBC gate, which should undergo a state-dependent conformational change. To this end, we replaced the Ala residue at position 161 with a Cys and labeled the resultant single-Cys A161C dimers with donors and acceptors, noting that A161C has a pH dependence similar to wild-type Kir1.1b (Fig. 5).

Since A161C is one residue below (cytoplasmic to) the hydrophobic HBC gate at L160-Kir1.1b, it should provide a good measure of the actual HBC dimensions as well as confirming that our LRET method can resolve small changes in distance.

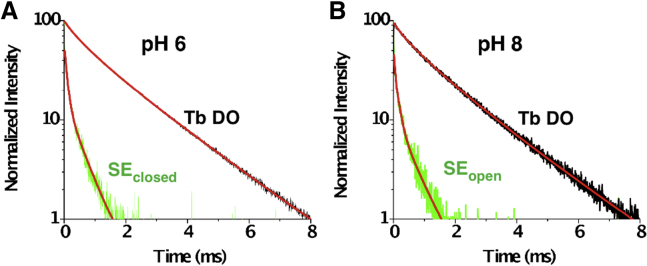

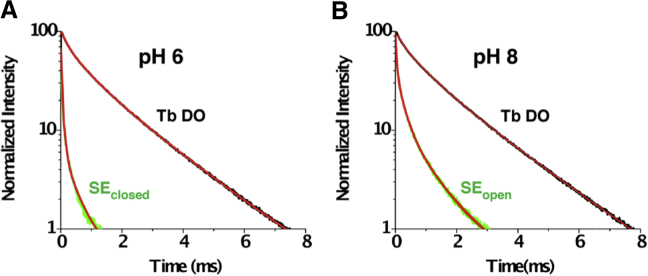

Lifetime luminescence decays (Fig. 8) for DO and SE were used to calculate the state-dependent distance between paired C161 residues on diagonally opposite subunits. These distances (r) are summarized in Table 3 for both fast and slow Tb donor states at pH 6 and pH 8. The half-maximal energy transfer distances (R0) for the Tb-Atto465-labeled pair were 21.1 Å and 26.5 Å for fast and slow Tb donor states, respectively.

Figure 8.

Normalized LRET lifetimes for A161C-Kir1.1b dimer proteoliposomes in 158 mM KMOPS. (A) Closed state at pH 6. (B) Open state at pH 8. A161C dimers were labeled with Tb chelate donor and Atto465 acceptor. Black tracings denote Tb DO signal, fitted with fast and slow Tb time constants (red lines). Green tracings are the corresponding sensitized acceptor (SE) lifetimes at (A) pH 6 (closed state) and (B) pH 8 (open state), together with exponential fits (red lines). Time constants are listed in Table 3, and additional calculations are in Supporting Material. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 3.

LRET Lifetime Decays and Calculated A161C-Kir1.1b Distances between Diagonally Opposite Subunits in the CTD

|

Data were obtained from energy transfer between Tb donors and Atto-465 acceptors on tetrameric A161C-Kir1.1b, self-assembled in proteoliposomes from single-Cys A161C dimers. τ denotes lifetime decay constants for donors and acceptor sensitized emission, f indicates fast donor state, and s indicates slow donor state. R0 is the distance corresponding to 50% energy transfer and r is the donor acceptor distance at the designated pH. The average distance between diagonal Cl61 residues in the CTD was 13.8 ± 2 Å at pH 6 and 22.6 ± 6 Å at pH 8.

Combining results from both donor states, we calculated an average C161 diagonal distance of 13.8 ± 2 Å for the closed state (pH 6) and 22.6 ± 6 Å for the open state (pH 8), implying an 8.8 ± 4 Å widening at C161-Kir1.1b during channel opening (Table 3).

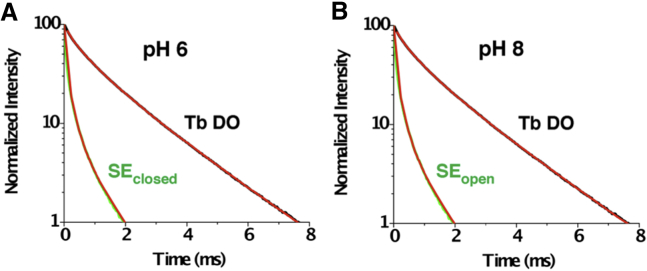

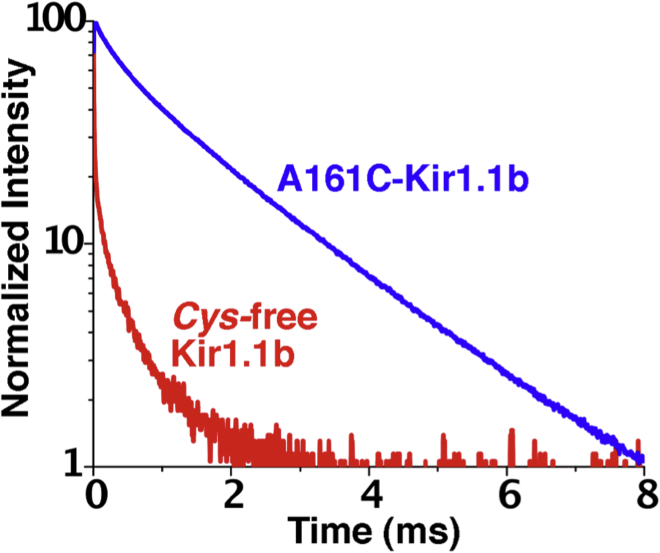

Contribution of background proteins to LRET signals

A possible source of error for LRET experiments utilizing a CF expression system is inadvertent labeling of extraneous proteins in the CF reaction mix (34). Consequently, we assessed the contribution of background proteins to the LRET signal by comparing a Cys-free Kir1.1b mutant to our single-Cys dimer protein (A161C-Kir1.1b). The presumption is that Tb luminescence from a Cys-free Kir1.1b proteoliposomes would reflect Tb maleimide binding to endogenous proteins in the CF wheat-germ system, thereby providing a measure of background contamination.

Cys-free Kir protein and single-Cys A161C dimer protein were produced and labeled with Tb chelate using identical CF protocols. Results of these experiments indicated that the donor signal from our single-Cys A161C dimer sample (blue, Fig. 9) was much stronger than the donor signal from the Cys-free sample (red, Fig. 9). This implies that there was very little contamination of our LRET data from extraneous wheat-germ proteins, even though we did not extensively purify the CF translation product. Furthermore, the absence of the characteristic (fast or slow) DO signals from the Cys-free Kir1.1 preparation indicates that our LRET-based distance measurements with single-Cys dimers were site specific.

Figure 9.

Contribution of background proteins to the terbium donor signal. Comparison of Tb DO signals from Cys-free Kir1.1b and A161C-Kir1.1b proteoliposomes. Both samples were produced using identical CF translation and labeling protocols. Red: Tb luminescence from the Cys-free tetrameric sample, representing background (non-Kir) contamination. Blue: Tb luminescence from the A161C tetrameric channel. To see this figure in color, go online.

Both the Cys-free sample and the single-Cys A161C dimer sample contained similar amounts of final liposomal protein (Fig. S3). In fact, the Cys-free sample had more wheat-germ heat-shock protein, Hsp70 (34), than the A161C dimer sample, but actually had a lower Tb donor luminescence (red, Fig. 9). This suggests that Hsp70 was not significantly labeled in our protocol.

It should be noted that our nominal Cys-free construct still contains two Cys residues (C102-Kir1.1b and C134-Kir1.1b) on each subunit that form a stabilizing sulfhydryl bridge near the extracellular turret of the channel. These residues cannot be removed without disrupting the tertiary structure and function of the channel. However, neither of these Cys appeared accessible to maleimide labeling, as confirmed by the small Tb signal in the nominally Cys-free sample (red, Fig. 9).

Discussion

Although conformational changes in the CTD are believed to initiate HBC gating of Kir1.1, details of this process are not well understood. Previous work with both prokaryotic and eukaryotic inward rectifiers have suggested different and sometimes contradictory mechanisms for the link between the CTD and the putative primary gate at the HBC. In our study, we combined several established techniques to assess state-dependent conformational changes in both the CTD and the HBC of the mammalian inward rectifier, Kir1.1b.

A CF wheat-germ system was used to produce single-Cys dimers that self-assembled into tetrameric channels, having a single donor and a single acceptor on opposite subunits (21). These were incorporated into anionic liposomes and either injected into oocytes or used for LRET (with PIP2). In the LRET experiments, distances between paired Cys in the CTD and near the HBC gate were determined from luminescence lifetime decays measured at pH 6 (closed state) and pH 8 (open state). The use of lifetime decays (26) rather than absolute FRET energies permits high-sensitivity structural determinations from a small batch of labeled CF protein that has not been exhaustively purified.

The LRET measurements with our three dimeric constructs are summarized in Table 4. State-dependent distances in the CTD at C189 and C289 indicated that pH gating was not correlated with expansion or contraction of the CTD. This is consistent with a model in which rigid body rotation of the CTD around the permeation axis produces an iris-like opening of the inward rectifier HBC gate (10). However, this result is at odds with single-molecule FRET studies in KirBac1.1 that indicated an association between HBC closure and either CTD widening (19) or CTD widening at one site and narrowing at another (20). We do not understand the reason for the difference between our macroscopic LRET measurements in Kir1.1b and the single-molecule FRET results in the bacterial KirBac 1.1 channel.

Table 4.

LRET Distances between Paired Diagonal Cys

|

Average LRET distances between Cys residues on diagonally opposite subunits. CTD indicates that the Cys pair is in the C-terminal domain. The C161 locus in the A161C mutant is near the HBC gate. The HBC values were calculated from our Kir1.1b homology model, which indicated that C161 was displaced 3.75 Å farther from the central axis of the channel than the actual hydrophobic gate at L160. Therefore, the HBC gate width will be 7.5 Å smaller than the distance between opposite C161 residues.

We also used LRET to measure Kir1.1b dimensions at one residue (C161) below (cytoplasmic to) the HBC gate at L160. Results indicated a diagonal distance of 13.8 ± 2 Å between opposite C161-Kir1.1b in the closed state (pH 6) and 22.6 ± 6 Å in the open state (pH 8). These values compare reasonably well with our homology model predictions of 11 Å for the closed state and 16.3 Å for the open state.

Since our Kir1.1b homology model indicated that C161 is 3.75 Å farther out from the central axis of the channel than L160, the width of the HBC gate at L160 will be 7.5 Å smaller than the C161-C161 diagonal distance (5). Consequently, the LRET-measured C161 distances of 13.8 ± 2 Å (closed state) and 22.6 ± 6 Å (open state) imply that the actual HBC gate increases from 6.3 ± 2 Å in the closed state to 15.1 ± 6 Å in the open state (Table 4). This would allow permeation of a 7 Å hydrated K ion through the open (but not the closed) state of the channel (Fig. 10).

These LRET measurements also support our hypothesis that the HBC gate is the primary barrier to K permeation in Kir1.1 channels. However, this is at odds with a KirBac1.1 crystallographic study that implicated the selectivity filter (rather than the HBC) as the primary gate of inward rectifier channels (11). Neither our data on Kir1.1b nor data from single-molecule FRET measurements on KirBac1.1 (19, 20) support the idea that the selectivity filter is the primary gate of inward rectifier channels. However, as we did not measure energy transfer between residues near the selectivity filter, we cannot absolutely exclude the filter as contributing to gating.

An unexpected benefit of combining CF protein translation with LRET is that it allows molecular distances to be determined from small quantities of minimally purified protein. Nonetheless, there are potential sources of error inherent in this methodology. First, the precise orientation of donor and acceptor labels on the single-Cys residues is not generally known and could produce a systematic error in absolute LRET distance. However, since label orientation is not pH dependent, orientation uncertainty cannot explain why the CTD dimensions at C189 and C289 are essentially unchanged during gating.

A second source of error in LRET measurements is inadvertent labeling of endogenous material in our CF system. We examined this possibility by translating and labeling a Cys-free sample of Kir1.1b, which provides a measure of endogenous CF material that could be inadvertently labeled. Results of these studies (Fig. 9) indicated very little labeling of endogenous CF components in our LRET proteoliposomes.

In conclusion, our LRET measurements at two locations in the CTD of the mammalian renal inward rectifier, Kir1.1b, indicated no significant contraction or expansion of the CTD during pH gating. This supports the hypothesis that rigid body rotation of the CTD around the pore axis is associated with opening of a primary gate at the HBC of inward rectifiers (10). Furthermore, LRET measurements between diagonally opposite Cys residues adjacent to the HBC indicated an 8.8 ± 4 Å widening of the L160-Kir1.1b hydrophobic gate from 6.3 ± 2 to 15.1 ± 6 Å during channel opening, allowing permeation of a 7 Å hydrated K.

Author Contributions

M.N. constructed the mutant DNA and produced, labeled, and verified the Kir proteoliposomes. J.E.S.-R., B.F., and H.S. ran the LRET and analyzed the data. F.B. designed hardware and software of the LRET system. H.S. designed the research plan and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK046950 (to H.S.), and GM030376 and U54GM087519 (to F.B.).

Editor: Baron Chanda.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, three figures, and three tables are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)31208-0.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Hebert S.C., Desir G., Wang W. Molecular diversity and regulation of renal potassium channels. Physiol. Rev. 2005;85:319–371. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00051.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNicholas C.M., Wang W., Giebisch G. Regulation of ROMK1 K+ channel activity involves phosphorylation processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:8077–8081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choe H., Zhou H., Sackin H. A conserved cytoplasmic region of ROMK modulates pH sensitivity, conductance, and gating. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;273:F516–F529. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.4.F516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNicholas C.M., MacGregor G.G., Giebisch G. pH-dependent modulation of the cloned renal K+ channel, ROMK. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:F972–F981. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.6.F972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sackin H., Nanazashvili M., Walters D.E. Structural locus of the pH gate in the Kir1.1 inward rectifier channel. Biophys. J. 2005;88:2597–2606. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.051474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y.Y., Sackin H., Palmer L.G. Localization of the pH gate in Kir1.1 channels. Biophys. J. 2006;91:2901–2909. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.087700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Posson D.J., McCoy J.G., Nimigean C.M. The voltage-dependent gate in MthK potassium channels is located at the selectivity filter. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:159–166. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Posson D.J., Rusinova R., Nimigean C.M. Calcium ions open a selectivity filter gate during activation of the MthK potassium channel. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8342. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson J., Begenisich T. Selectivity filter gating in large-conductance Ca(2+)-activated K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2012;139:235–244. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bavro V.N., De Zorzi R., Tucker S.J. Structure of a KirBac potassium channel with an open bundle crossing indicates a mechanism of channel gating. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:158–163. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke O.B., Caputo A.T., Gulbis J.M. Domain reorientation and rotation of an intracellular assembly regulate conduction in Kir potassium channels. Cell. 2010;141:1018–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen S.B., Tao X., MacKinnon R. Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature. 2011;477:495–498. doi: 10.1038/nature10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tao X., Avalos J.L., MacKinnon R. Crystal structure of the eukaryotic strong inward-rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2 at 3.1 Å resolution. Science. 2009;326:1668–1674. doi: 10.1126/science.1180310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whorton M.R., MacKinnon R. Crystal structure of the mammalian GIRK2 K+ channel and gating regulation by G proteins, PIP2, and sodium. Cell. 2011;147:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whorton M.R., MacKinnon R. X-ray structure of the mammalian GIRK2-βγ G-protein complex. Nature. 2013;498:190–197. doi: 10.1038/nature12241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riven I., Kalmanzon E., Reuveny E. Conformational rearrangements associated with the gating of the G protein-coupled potassium channel revealed by FRET microscopy. Neuron. 2003;38:225–235. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J.R., Shieh R.C. Structural changes in the cytoplasmic pore of the Kir1.1 channel during pHi-gating probed by FRET. J. Biomed. Sci. 2009;16:29–35. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang S., Lee S.J., Nichols C.G. Structural rearrangements underlying ligand-gating in Kir channels. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:617–624. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang S., Vafabakhsh R., Nichols C.G. Structural dynamics of potassium-channel gating revealed by single-molecule FRET. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016;23:31–36. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadler E.E., Kapanidis A.N., Tucker S.J. Solution-based single-molecule FRET studies of K(+) channel gating in a lipid bilayer. Biophys. J. 2016;110:2663–2670. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faure É., Starek G., Blunck R. A limited 4 Å radial displacement of the S4-S5 linker is sufficient for internal gate closing in Kv channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:40091–40098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.415497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Endo Y., Sawasaki T. Cell-free expression systems for eukaryotic protein production. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2006;17:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarecki B.W., Makino S., Chanda B. Function of Shaker potassium channels produced by cell-free translation upon injection into Xenopus oocytes. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1040–1046. doi: 10.1038/srep01040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sackin H., Nanazashvili M., Makino S. Direct injection of cell-free Kir1.1 protein into Xenopus oocytes replicates single-channel currents derived from Kir1.1 mRNA. Channels (Austin). 2015;9:196–199. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2015.1063752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lakowicz J.R. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Springer Science; Berlin, Germany: 2006. Theory of Energy transfer for a donor-acceptor pair; pp. 445–448. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selvin P.R. Principles and biophysical applications of lanthanide-based probes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2002;31:275–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.101101.140927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J., Selvin P.R. Thiol-reactive luminescent chelates of terbium and europium. Bioconjug. Chem. 1999;10:311–315. doi: 10.1021/bc980113w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nimigean C.M. A radioactive uptake assay to measure ion transport across ion channel-containing liposomes. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1207–1212. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sackin H., Nanazashvili M., Walters D.E. An intersubunit salt bridge near the selectivity filter stabilizes the active state of Kir1.1. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1058–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandtner W., Bezanilla F., Correa A.M. In vivo measurement of intramolecular distances using genetically encoded reporters. Biophys. J. 2007;93:L45–L47. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.119073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bollepalli M.K., Fowler P.W., Baukrowitz T. State-dependent network connectivity determines gating in a K+ channel. Structure. 2014;22:1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooks B.R., Bruccoleri R.E., Karplus M. CHARMM: a program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 1983;4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacKerell A.D., Bashford D., Karplus M. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goren M.A., Fox B.G. Wheat germ cell-free translation, purification, and assembly of a functional human stearoyl-CoA desaturase complex. Protein Expr. Purif. 2008;62:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.