Abstract

F1-ATPase is a rotary motor protein driven by ATP hydrolysis. Among molecular motors, F1 exhibits unique high reversibility in chemo-mechanical coupling, synthesizing ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate upon forcible rotor reversal. The ε subunit enhances ATP synthesis coupling efficiency to > 70% upon rotation reversal. However, the detailed mechanism has remained elusive. In this study, we performed stall-and-release experiments to elucidate how the ε subunit modulates ATP association/dissociation and hydrolysis/synthesis process kinetics and thermodynamics, key reaction steps for efficient ATP synthesis. The ε subunit significantly accelerated the rates of ATP dissociation and synthesis by two- to fivefold, whereas those of ATP binding and hydrolysis were not enhanced. Numerical analysis based on the determined kinetic parameters quantitatively reproduced previous findings of two- to fivefold coupling efficiency improvement by the ε subunit at the condition exhibiting the maximum ATP synthesis activity, a physiological role of F1-ATPase. Furthermore, fundamentally similar results were obtained upon ε subunit C-terminal domain truncation, suggesting that the N-terminal domain is responsible for the rate enhancement.

Introduction

FoF1-ATP synthase (FoF1) is one of the most ubiquitous enzymes, which mediates energy conversion among heterogeneous energy sources; in particular, by catalyzing ATP synthesis from ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi) by using the proton motive force (pmf) across biomembranes (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). The prominent feature of FoF1 is that mechanical rotation of the inner rotor complex mediates heterogeneous energy conversion with high efficiency and reversibility. FoF1 comprises two rotary motors (6), Fo and F1. Fo, the membrane-embedded component of FoF1, is a rotary motor driven by the proton flux down the pmf (7, 8). F1, the water-soluble element of FoF1, is an ATP-driven rotary motor protein, in which the rotary shaft rotates against the surrounding stator upon ATP hydrolysis. In a cell, Fo and F1 are connected by a common rotary shaft and peripheral stalk that transmit their competing rotary torques. When the pmf is sufficiently large, Fo rotates the rotor against F1, leading to ATP synthesis in F1. When the pmf is diminished, F1 hydrolyses ATP to rotate the rotor complex in reverse, enforcing Fo to pump the protons.

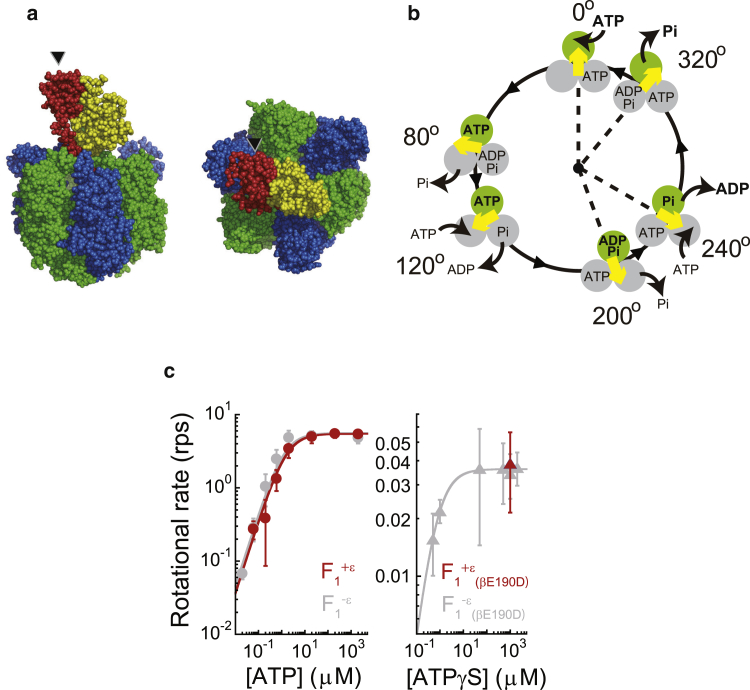

F1, the main target of this study, is composed of α3β3γδε; the minimum complex as a rotary motor is the α3β3γ subcomplex (Fig. 1 a). Of these, three α and three β subunits form the α3β3 stator ring with a central cavity that accommodates the central rotary shaft γ (9, 10, 11). The catalytic reaction centers for ATP hydrolysis/synthesis reside at the αβ interfaces, mainly on the β subunit. Upon ATP hydrolysis, F1 rotates in the anticlockwise direction (12) (when viewed from the membrane side), in which the three β subunits cooperatively change their conformation (13), generating a rotary torque of 40 pN·nm for the F1 from thermophilic Bacillus PS3 (14) and 20–74 pN·nm for the F1 from Escherichia coli (15, 16, 17). The energy required for the mechanical work for one γ rotation is mostly equivalent to the hydrolysis of three ATP molecules (14, 18). Therefore, F1 is extremely efficient in converting chemical energy to mechanical work; i.e., the catalysis is tightly coupled to the mechanical work. To elucidate the fundamental rotation properties, single-molecule studies have been extensively carried out for F1 from thermophilic Bacillus PS3 (19), which was also used in this study. Fig. 1 b shows the presently accepted scheme of chemo-mechanical coupling of F1 from thermophilic Bacillus PS3 (20). Hydrolysis or turnover of a single ATP molecule at each catalytic site is coupled to one revolution of the γ subunit, with the angle between the three catalytic sites differing by 120° during each catalytic phase. The unitary step size of the rotation of F1 is 120° and each step is coupled to a single turnover of ATP hydrolysis (14). The 120° step is further divided into 80 and 40° substeps (21, 22). The 80° substep is triggered by ATP binding and ADP release, each of which occurs on different β subunits. The 40° substep is triggered by ATP hydrolysis and the release of Pi, which also occurs on different β subunits. The angular positions of F1 before the 80 and 40° substeps are referred to as the ATP-binding and catalytic angles, respectively. When the β subunit ATP-binding angle is 0° (green circle in Fig. 1 b), it executes a hydrolysis reaction after the γ subunit rotates by 200° and releases ADP and Pi at 240 and 320°, respectively (20, 23, 24, 25). When the γ subunit returns to the original angular position, the β subunit initiates the next round of catalysis by binding to a new ATP. Thus, the reaction sequences among the three β subunits are well coordinated at the resolution of elementary reaction steps, which contributes to the reversibility of the chemo-mechanical coupling on F1.

Figure 1.

Rotary catalysis of F1-ATPase. (a) Crystal structure of the α3β3γε complex, F1+ε, from thermophilic Bacillus PS3 (PDB: 4XD7). The α, β, γ, and ε subunits are colored in blue, green, yellow, and red, respectively. The black arrowheads indicate the ε subunit. (b) Chemo-mechanical coupling scheme of F1 at low ATP concentration. The circles and yellow arrows represent the catalytic state of the β subunits and the angular positions of the γ subunit. Each β subunit completes one turnover of ATP hydrolysis in a turn of the γ subunit, where the three β subunits vary in their catalytic phase by 120°. Regarding the catalytic state of the top β subunit (green), ATP binding, hydrolysis, ADP release, and inorganic phosphate (Pi) release occur at 0, 200, 240, and 320°, respectively. (c) The rotational velocity (V) of F1+ε (red, left panel), F1−ε (gray, left panel), F1+ε(βE190D) (red, right panel), and F1−ε(βE190D) (gray, right panel) obtained using magnetic beads at various ATP or ATPγS concentrations. The curves represent Michaelis–Menten fits with V = Vmax[ATP]/([ATP] + Km), where Vmax = 5.5 and 5.6 s−1, Km = 2.0 and 1.2 μM, and the corresponding ATP-binding rate, kon = 3 × Vmax/Km; 0.8 × 107 and 1.4 × 107 M−1·s−1 for F1+ε and F1−ε, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

The reversible chemo-mechanical coupling is regulated by several mechanisms that differ among species (26); e.g., in bacteria, the ε subunit functions as a main regulator of the reversible coupling. The ε subunit, which is intrinsically bound to the γ subunit as a part of the rotor complex (Fig. 1 a) (10, 27), has been known as an endogenous inhibitor of ATP hydrolysis (28, 29) as well as enhancing the coupling efficiency upon ATP synthesis by almost fivefold (30, 31). The ε subunit has a two-domain structure, N-terminal β-sandwich and C-terminal dual α-helices (32). The C-terminal domain shows a conformational transition between “hairpin-folded” and “extended” states upon ATP association or dissociation, such that the hairpin-folded state is stabilized upon ATP binding (33, 34), whereas the N-terminal domain is itself stable, forming a binding interface toward the protruding part of the γ subunit. The extensive studies related to the ε subunit have shown that, in general, the C-terminal domain inhibits ATP hydrolysis by extending its conformation, whereas conversely, the hairpin-folded state does not affect the kinetic and rotation properties of F1 in ATP hydrolysis mode; however, the correlation between ε subunit conformation and its effect on ATP synthesis has remained elusive. Moreover, the mechanism by which the ε subunit regulates the chemo-mechanical coupling at the resolution of elementary reaction steps has not been well characterized.

To evaluate kinetic properties during γ rotation, in previous studies we developed, to our knowledge, a novel method, the stall-and-release experiment, to measure the rate and equilibrium constant of the F1 reaction at an elementary step resolution (20, 35, 36). Through this method, we arrested F1 in the transient conformation using magnetic tweezers and observed the behavior of F1 immediately after release from arrest. The analysis of the behavior of F1 allowed us to simultaneously determine the rate constant for each forward and reverse step of the reaction at various rotational angles; e.g., ATP binding and release, or hydrolysis and synthesis. Thus, we could also measure the equilibrium constant of each reaction step in the catalytic cycle. Because the equilibrium constant is a measure of the difference in the free energy of the pre- and postreaction states, ΔG(θ) = −kBT·lnKE(θ), the torque generated during each reaction step could also be estimated from the derivative of the free energy, dΔG(θ)/dθ.

In this study, we performed the stall-and-release experiment to elucidate how the ε subunit modulates or its conformation affects the rate and equilibrium constants of hydrolysis or synthesis at an elementary step resolution to achieve the highly reversible chemo-mechanical coupling. The results revealed that the ε subunit increased the rate constants of the reverse reaction steps, and ATP release and synthesis, by two- to fivefold, which was also observed using ε without its C-terminal domain (εΔc), whereas it did not affect those of the forward reaction steps, i.e., ATP binding and hydrolysis (29, 37). These findings have important implications for the molecular mechanisms of the highly reversible chemo-mechanical coupling of F1, as exclusively achieved among molecular motor proteins driven by ATP hydrolysis.

Materials and Methods

Rotation assay

The samples of F1 and ε subunits were prepared as previously reported (31). To visualize the rotation of F1, the stator subunits (α3β3), which carried His-tags at the N-terminus, were fixed on a glass surface modified with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid, and a streptavidin-coated magnetic bead (ϕ = ∼0.2 μm; Seradyn, Indianapolis, IN) was attached on the top of a biotinylated rotor subunit (γ) to probe rotation. The procedures were as follows. First, the flow chamber was constructed from an uncoated top coverglass and a bottom coverglass modified with Ni-nitrilotriacetic for immobilization of His-tagged F1. F1 was diluted with buffer A (50 mM 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid-KOH and 50 mM KCl, pH 7.0) to a final concentration of 200 pM and then infused into the flow chamber. After 5 min, unbound F1 molecules were washed out with buffer A containing 10 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, then streptavidin-coated beads in buffer A were infused. After 10 min, unbound beads were washed out with buffer A. Finally, buffer A containing the indicated amount of Mg-ATP and Mg-ATPγS was infused. The rotating beads were observed under a phase-contrast microscope (IX-70 or IX-71; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a 100× objective lens. The rotation assay was performed at 25 ± 3°C.

Manipulation with magnetic tweezers

The microscope stage was equipped with magnetic tweezers controlled by custom software (Celery, Library, Japan) (36). The rotary motion of the bead was imaged at 30 frames/s (FC300M; Takex America, Inc., Takex, Kyoto, Japan) for the experiments in Figs. 3, 4, and 5 or at 1000 frames/s (FASTCAM 1024PCI-SE; Photron, Tokyo, Japan) for the experiments in Fig. 1 d. Images were stored in the hard disk drive of a computer as audio video interleave files and analyzed using custom software (36).

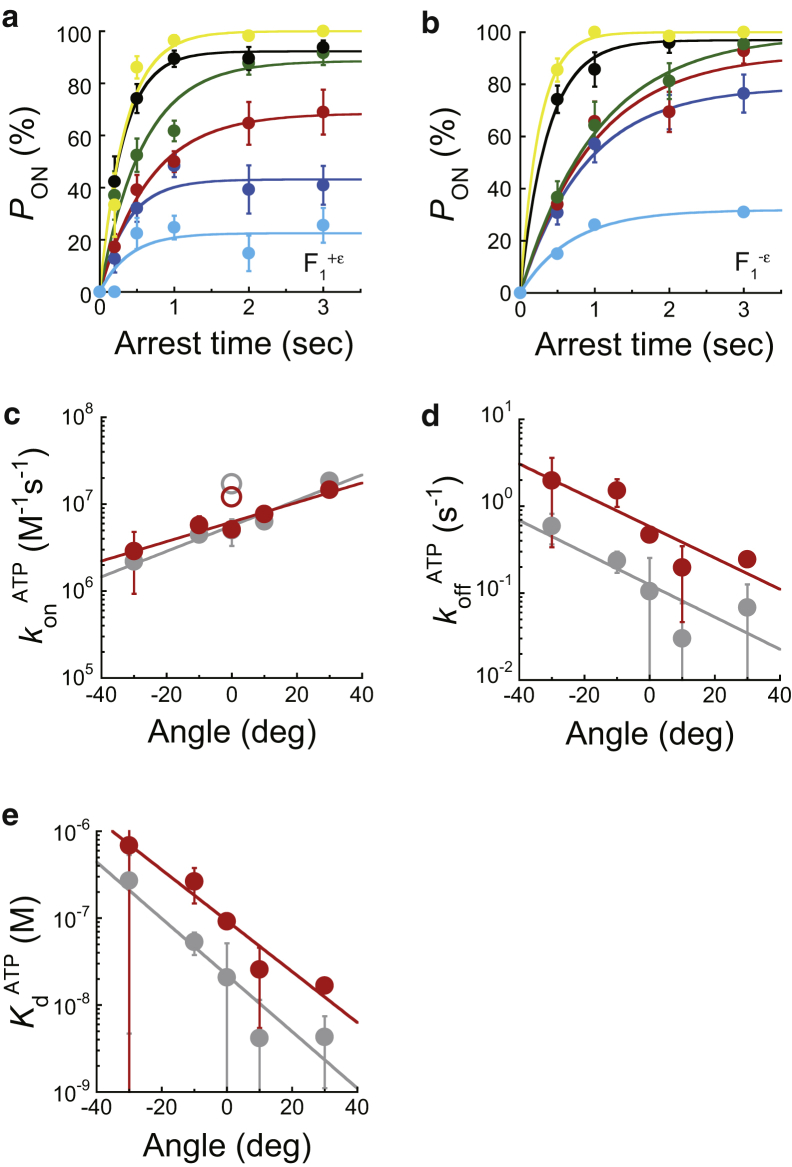

Figure 3.

Angle dependence of ATP binding and release. (a and b) Time courses of pON of F1+ε (a) and F1−ε (b) at 200 nM ATP after stalling at −30° (cyan), −10° (blue), 0° (red), +10° (green), +30° (black), or +50° (yellow) from the original ATP-binding angle. konATP and koffATP were determined by fitting to a single exponential function: pON = (konATP·[ATP]/(konATP[ATP] + koffATP)) × (1 − exp(−(konATP[ATP] + koffATP) × t)), according to the reversible reaction scheme, F1 + ATP ⇄ F1∙ATP. Each data point was obtained from 29 to 80 trials using more than five molecules. The error in pON is given as , where N is the number of trials for each stall measurement. (c–e) Angle dependence of konATP, koffATP, and KdATP plotted against the arrest angle. Zero degrees corresponds to the ATP-binding angle in Fig. 1b. The open symbols represent the konATP determined from freely rotating F1. Red and gray symbols represent the values for F1+ε and F1−ε, respectively. deg, degree. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 4.

Angle dependence of ATPγS hydrolysis, synthesis, and Thio-Pi release. (a and b) Time courses of pON of F1+ε(βE190D) (a) and F1−ε(βE190D) (b) at 1 mM ATPγS after stalling at −50° (blue), +10° (red) or +50° (green) from the original hydrolysis waiting angle (200° in Fig. 1b). khydATPγS, ksynATPγS, KEATPγS, and koffThio-Pi were determined by fitting to a consecutive reaction model. Each data point was obtained from 12 to 78 trials using more than five molecules. The error in pON is given as , where N is the number of trials for each stall measurement. (c–f) Angle dependence of khydATPγS, ksynATPγS, KEATPγS, and koffThio-Pi plotted against arrest angle. Zero degrees corresponds to the hydrolysis angle in Fig. 1b. Red and gray symbols represent the values for F1+ε(βE190D) and F1−ε(βE190D), respectively. deg, degree. To see this figure in color, go online.

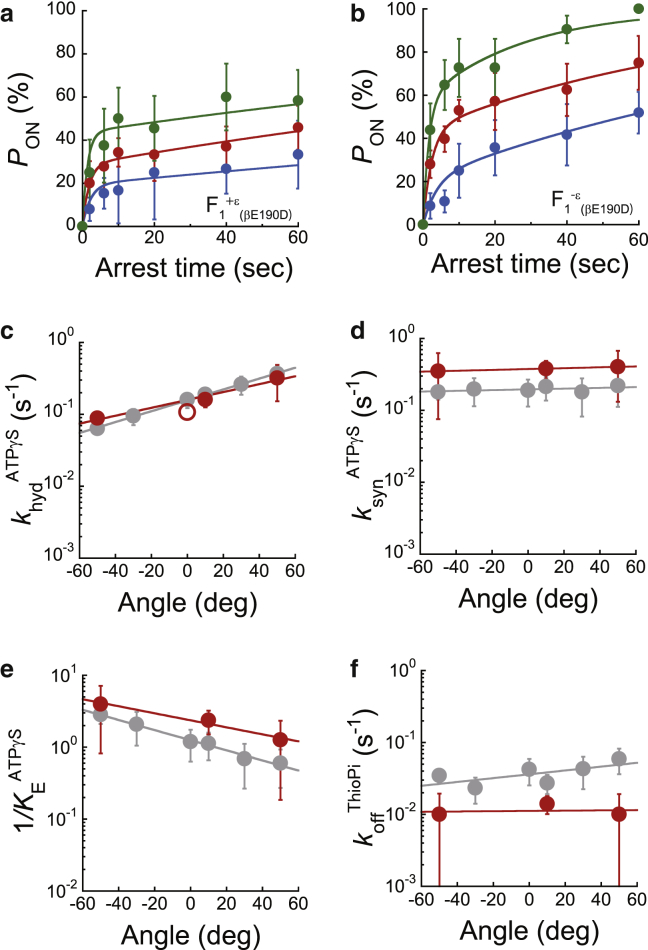

Figure 5.

Buffer exchange experiments. (a) Schematic of buffer exchange experiments: pON measured for a target F1 molecule, exchanged with the buffer including 50 nM ε subunits for the reconstitution of F1+ε or F1+ε(βE190D) complex, and then pON measured again. (b) Left panel shows the time course of pON of F1+ε (red) and F1−ε (gray) at 200 nM ATP determined from the ensemble average at ± 0°. pON at 3 s was highlighted using a yellow bar. Right panel shows pON determined by buffer exchange experiments, with a stall at ± 0° for 3 s for the same rotating molecules before (gray) and after reconstitution of the ε subunit (red). The pON for each molecule is displayed using different symbols. The open circles represent the averages of seven molecules. (c) Left panel shows the time course of pON of F1+ε(βE190D) (red) and F1−ε(βE190D) (gray) at 1 mM ATPγS determined from the ensemble average at ± 0°. pON at 20 s was highlighted using a yellow bar. Right panel shows PON determined by buffer exchange experiments, with a stall at ± 0° for 20 s for the same rotating molecules before (gray) and after reconstitution of the ε subunit (red). The pON for each molecule is displayed using different symbols. The open circles represent the averages of four molecules. w/o, without; w/, with. To see this figure in color, go online.

Results

Rotary motion of F1 in the presence of the ε subunit

All of the subunit components for F1 used in this study were originated from F1 from thermophilic Bacillus PS3 (TF1). The α3β3γε complex of F1, which is referred as to F1+ε for simplicity, was reconstituted by mixing the ε subunit with the α3β3γ complex (Fig. 1 a). The α3β3γ complex is subsequently referred as to F1−ε. The binding of the ε subunit to F1−ε was confirmed using gel-filtration chromatography and single-molecule fluorescence analysis (Figs. S1 and S2). In the rotation assay with magnetic beads as a rotation probe (ϕ = ∼200 nm), actively rotating particles that showed continuous rotation without lapsing into ε inhibition were selectively observed in the presence of ATP in the range from 60 nM to 2 mM. The rotation rate of F1+ε obeyed a Michaelis–Menten curve with a maximum rotational rate, Vmax, of 5.5 s−1 and a Michaelis constant, Km, of 1.5 μM (red, Fig. 1 c). The rate constant of ATP binding, konATP, was determined as 3 × Vmax/Km to be 1.1 × 107 M−1·s−1, which is almost the same as that for F1−ε, 1.4 × 107 M−1·s−1 (gray, Fig. 1 c); i.e., the ε subunit does not affect the kinetic property of freely rotating F1.

In this study, we used the βE190D mutant, F1 (βE190D), which retards the rate constant of ATP hydrolysis by 300-fold, to facilitate the stall-and-release experiment for the hydrolysis step (21, 36). To investigate the effect of the ε subunit on this mutant, we conducted a rotation assay for F1+ε(βE190D). At 1 mM ATPγS, where the rate-limiting step is the hydrolysis of ATPγS, the rotational rate of F1+ε(βE190D) was 0.039 revolutions/s (Fig. 1 c), which is almost the same as that for F1−ε(βE190D). Thus, it was shown that the ε subunit does not affect the kinetic property of the hydrolysis step for the freely rotating βE190D mutant.

Manipulation of single F1 rotation

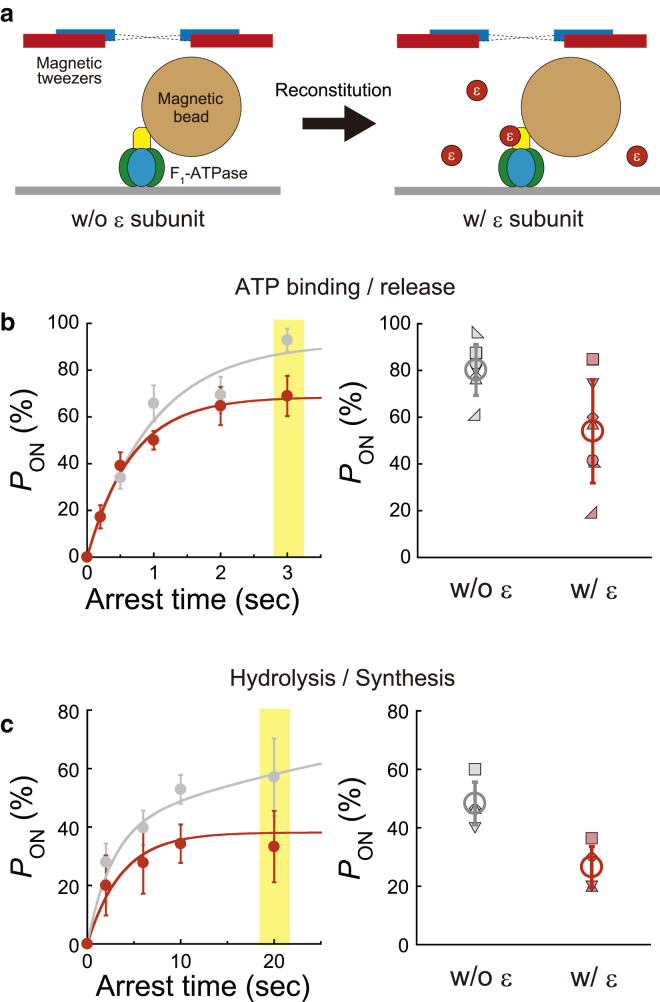

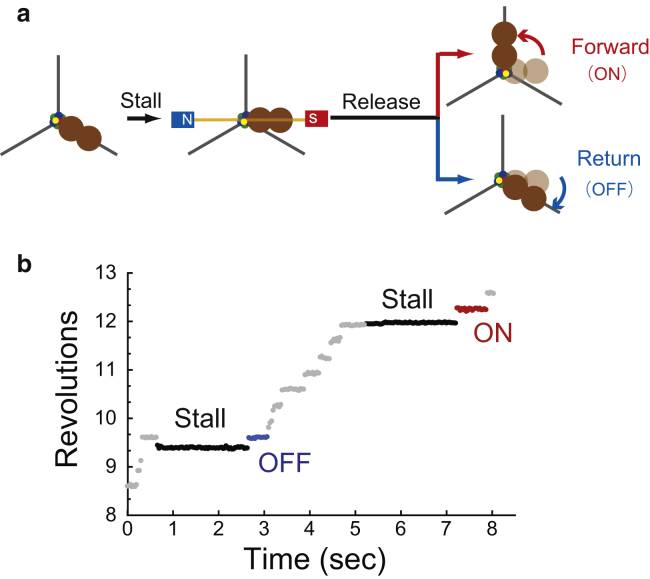

To investigate how the ε subunit affects the angle-dependent affinity change of ATP binding and equilibrium change of hydrolysis, we conducted stall-and-release experiments using F1+ε to measure ATP binding and F1+ε(βE190D) to measure hydrolysis. Experimental procedures were essentially the same as for previous stall-and-release experiments (Fig. 2 a) (36, 38). First, we turned on the magnetic tweezers to arrest F1 at the target angle when F1 paused for ATP binding or hydrolysis (Fig. 2 a). At the designated time, we turned off the magnetic tweezers to release F1 from arrest. After release, F1 showed one of two behaviors: a forward 120° step (“ON” event) or a resumed pause at the original pause angle (“OFF” event) (Fig. 2). The ON event indicates that F1 completed the waiting reaction and exerted a torque on the magnetic probes (red, Fig. 2); conversely, the OFF event shows that the waiting reaction had not been completed (blue, Fig. 2). F1 was stalled at the angle range of ± 50°. Note that we defined the stall angle of “0°” as the original pause angle, which corresponds to 0 and 200° in Fig. 1 b for ATP binding and hydrolysis, and assigned the positive value to the stall angle in counterclockwise fashion. The subsequent sections discuss analysis of the probability of ON events against total trials, pON.

Figure 2.

Single-molecule manipulation with magnetic tweezers. (a) Schematic of manipulation procedures. When F1 paused at the ATP-binding or hydrolysis dwell, the magnetic tweezers were turned on to stall F1 at the target angle then turned off to release the motor after the set time. Released F1 either steps forward (ON) or returns to the original pause angle (OFF). These behaviors indicate that the reaction under investigation has completed or not, respectively. (b) Examples of stall-and-release traces for ATP binding of F1+ε at 200 nM ATP. During a pause, F1+ε was stalled for 2 s and then released. After release, F1+ε stepped to the next binding angle without moving back (red), indicating that ATP had already bound to F1+ε before release. When stalled for 2 s, F1+ε rotated back to the original binding angle (blue), indicating that no ATP binding had occurred. To see this figure in color, go online.

Angle dependence of ATP binding/release

The stall-and-release experiments were conducted using F1+ε at 200 nM ATP where the ATP-waiting time was 0.41 s (yellow, Fig. S3 a). As shown in Fig. 3 a, pON increased with both the stall angle and stall time, which is similar to our previous finding of ATP binding by F1−ε (36). In addition, pON was not always 100% saturated, although it converged to a certain value within 3 s. The values of pON at 3 s obtained using F1+ε were smaller than those of F1−ε; e.g., 69 and 93% for ± 0° stall of F1+ε and F1−ε, respectively (red lines in Fig. 3, a and b). These observations imply that ATP binding is reversible in this time range, such that ATP release also occurs during stalling. Accordingly, the plateau level indicates the equilibrium level between ATP binding/release.

To confirm that F1 transits the catalytic states between the ATP-waiting or ATP-bound state without lapsing into an unexpected state such as ADP or ε inhibition, we analyzed the dwell time of F1+ε to spontaneously conduct a 120° step after an OFF event (blue, Fig. 2 b). Here, only experiments with longer stalling times in which pON achieved a plateau were analyzed to avoid including data before the equilibrium. The obtained dwell time histogram showed a single exponential decay, providing the rate constant (green, Fig. S3 a). As expected, the determined rate constant corresponded to that for free rotation (yellow, Fig. S3 a). This correspondence excluded the possibility of unexpected inactivation; e.g., ε inhibition. We also plotted a histogram of the dwell time to conduct the second 120° step after the ON event (red, Fig. 2 b). The histogram was also in good agreement with that of free rotation (red, Fig. S3 a), confirming that manipulation did not alter the kinetic properties of F1+ε at the ATP hydrolysis condition.

By fitting time courses of pON based on a reversible reaction scheme, F1 + ATP ⇄ F1·ATP, the rate constants of ATP binding and release, konATP and koffATP, were determined for each stall angle. The konATP increased exponentially with stall angle by 1.7-fold per 20° (red, Fig. 3 c), the koffATP decreased exponentially by 2.2-fold per 20° (red, Fig. 3 d), and the dissociation constant of ATP, KdATP, accordingly decreased 3.9-fold per 20° (red, Fig. 3 e), which was a similar trend as that of F1−ε (gray, Fig. 3, c–e). In contrast to the similar angle dependence, the koffATP of F1+ε was almost fivefold larger than that of F1−ε, independent of the rotary angle, showing that the ε subunit enhances the rate constant of ATP release; i.e., inclines the equilibrium toward ATP release.

Angular dependence of hydrolysis/synthesis

For the wild-type F1, the dwell time for ATP hydrolysis is only 1 ms, which is too short for stalling with magnetic tweezers. Therefore, we conducted the stall-and-release experiment using the hydrolysis reaction of the ATP analog, ATPγS, and a mutant, F1+ε(βE190D), both of which retard the hydrolysis rate by 10,000-fold (21), such that F1+ε(βE190D) showed a 120° stepping rotation, yielding hydrolysis-waiting pauses of 9.3 s (yellow, Fig. S3 b) (21, 36). Then, F1+ε(βE190D) in the hydrolysis pause was stalled for 2–60 s with magnetic tweezers to determine pON. As shown previously (36), pON increased in two phases (Fig. 4 a); however, the slope of the second increase was more gradual than that obtained using F1−ε(βE190D) (Fig. 4 b). The first increase was nearly complete within 20 s, which is consistent with the time constant of ATPγS hydrolysis. The subsequent increase was extremely slow for an effective catalytic reaction. We previously showed that this slow increase results from the release of thio-phosphate (Thio-Pi) by the β subunit that hydrolyzed the bound ATPγS (Fig. 1 b, 200° state) during stalling (36). To confirm that F1 does not lapse into an unexpected state before Thio-Pi release, we analyzed the dwell time of F1 to spontaneously conduct a 120° step after an OFF event. Here, experimental stalling for 20 s, in which the first increase of pON achieved a plateau whereas the second increase rarely occurred, was analyzed to avoid including data under a nonequilibrium state owing to Thio-Pi release. The obtained dwell time histogram showed a single exponential decay, providing the rate constant (green, Fig. S3 b). As expected, the determined rate constant corresponded to that for free rotation (yellow, Fig. S3 b). This correspondence excluded the possibility of unexpected inactivation; e.g., ADP inhibition. We also plotted a histogram of the dwell time to conduct the second 120° step after the ON event. The histogram was also in good agreement with that of free rotation (red, Fig. S3 b), confirming that manipulation did not alter the kinetic properties of F1+ε(βE190D) in the hydrolysis condition.

By fitting time courses of pON based on a consecutive reaction model with a reversible hydrolysis step followed by irreversible Thio-Pi release at 200°, F1(βE190D)·ATPγS ⇄ F1(βE190D)·(ADP + Thio-Pi) → F1(βE190D)·ADP + Thio-Pi, the rate constants of ATPγS hydrolysis, synthesis, and Thio-Pi release—khydATPγS, ksynATPγS, and koffThio-Pi—were determined for each stall angle. The khydATPγS increased exponentially with stall angle (red, Fig. 4 c), whereas the ksynATPγS remained constant (red, Fig. 4 d). The equilibrium constant of hydrolysis, (khydATPγS/ksynATPγS = KEATPγS) showed relatively weak angle dependence when compared with that of ATP binding KdATP (red, Fig. 4 e), which was a similar trend as that of F1−ε(βE190D) (gray, Fig. 4, c–e). In contrast to the similar angle dependence, the ksynATPγS was almost twofold larger than that of F1−ε(βE190D), independent of the rotary angle, showing that the ε subunit enhances the rate constant of ATPγS synthesis; that is, inclines the equilibrium to ATPγS synthesis. The koffThio-Pi was constant around 0.01 s−1; i.e., almost fourfold smaller than that of F1−ε(βE190D) (Fig. 4 f), showing that the ε subunit suppresses the Thio-Pi release at around 200°.

Buffer exchange experiment

To confirm the equilibrium shift owing to the ε subunit, we measured pON, a barometer of the equilibrium level, before and after reconstitution of the ε subunit for F1 molecules under observation by conducting buffer exchange experiments: we measured pON for a target F1 molecule (F1−ε or F1−ε(βE190D) complex), exchanged the buffer including 50 nM ε subunits for reconstitution of the F1+ε or F1+ε(βE190D) complex, and then again measured pON (Fig. 5 a). For the ATP-binding step, we conducted the stall-and-release experiment at ± 0° for 3 s, where the ensemble averages of pON were 93% and 69% for F1−ε and F1+ε, respectively (left, Fig. 5 b). The buffer exchange experiment showed that all F1 molecules exhibited decreased pON for ATP binding by ∼26% after reconstitution of the ε subunit (right, Fig. 5 b), which corresponds to the ensemble results (left, Fig. 5 b). In addition, we conducted the stall-and-release experiment for the hydrolysis step of F1−ε(βE190D) at +10° for 20 s, where the ensemble averages of pON were 52 and 34% for F1−ε(βE190D) and F1+ε(βE190D), respectively (left, Fig. 5 c). The buffer exchange experiment showed that all F1(βE190D) molecules exhibited decreased PON for hydrolysis by ∼22% after reconstitution of the ε subunit (right, Fig. 5 c), which also coincided with the ensemble results (left, Fig. 5 c). Thus, it was again confirmed that the ε subunit inclined the equilibrium toward ATP synthesis at the resolution of elementary reaction steps, which would contribute to highly efficient synthesis of ATP, a prominent feature of F1 among molecular motor proteins.

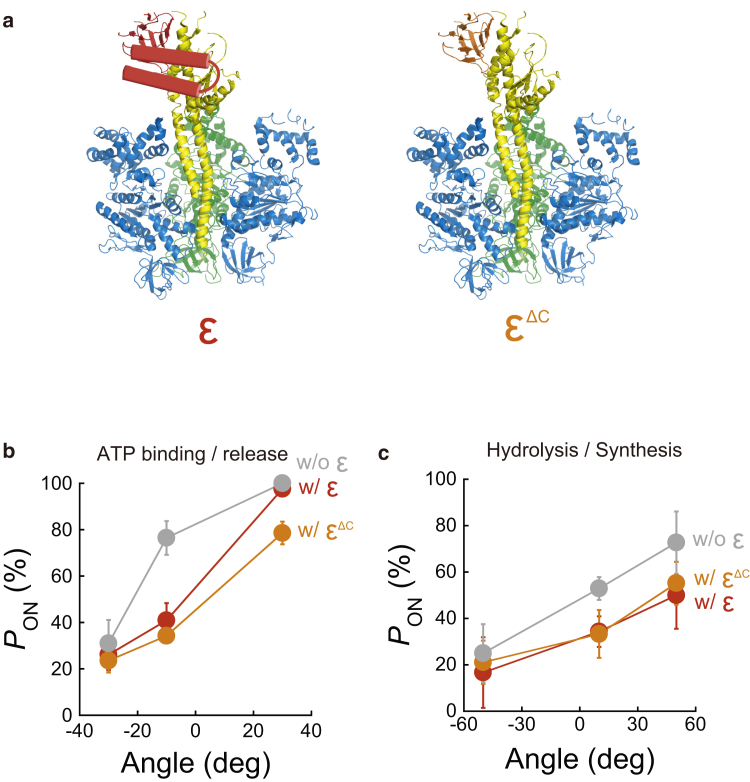

The role of individual domains on the ε subunit for rotary catalysis

The ε subunit has a two-domain structure consisting of an N-terminal β-sandwich and C-terminal α-helices (Fig. 6 a). To understand the role of individual domains on the regulatory mechanism, we again measured pON using a truncated ε subunit (εΔc) that did not contain the C-terminal α-helices (orange in Fig. 6 a) (39). For the ATP-binding step, we conducted the stall-and-release experiment at ± 30° for 3 s, where the equilibrium of ATP binding achieved a plateau level as mentioned above (Fig. 3 a). The pON of F1+εΔc almost coincided with that of F1+ε, being smaller than F1−ε (Fig. 6 b). In addition, we conducted the experiment for the hydrolysis step of F1−ε(βE190D) at ± 50° for 20 s, where the equilibrium of hydrolysis also achieved a plateau level (Fig. 4 a). The pON of F1+εΔc(βE190D) also coincided with that of F1+ε(βE190D) (Fig. 6 c), showing that the N-terminal β-sandwich of the ε subunit contributes to highly efficient synthesis of ATP, whereas the C-terminal α-helices do not. This result is consistent with that of a previous biochemical study using chloroplast F1, in which the effect of the N-terminal domain of the ε subunit was found to be higher than that of the C-terminal domain (40).

Figure 6.

C-terminal domain of the ε subunit. (a) Cross section view of F1+ε (left) and F1+εΔc (right) from thermophilic Bacillus PS3 (PDB: 4XD7). The C-terminal α-helices of the ε subunit are illustrated using cylindrical diagrams. The ε subunits with (ε) or without C-terminal α-helices (εΔc) are colored in red and orange, respectively. (b) pON at 200 nM ATP for F1−ε (gray), F1+ε (red), and F1+εΔc (orange) were plotted against the arrest angle. (c) pON at 1 mM ATPγS for F1−ε(βE190D) (gray), F1+ε(βE190D) (red), and F1+εΔc(βE190D) (orange) were plotted against the arrest angle. deg, degree; w/o, without; w/, with. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

The ε subunit modulates the catalytic reaction rate of F1 in an asymmetric manner; i.e., ATP release and the phosphoester bond formation of ATP on the catalytic site are accelerated, whereas ATP binding and the cleavage of ATP are not significantly changed. As previously reported, the major rate-limiting step of ATP synthesis is thought to be the ATP release step (41). Thus, the enhancement of ATP release by the ε subunit should improve the overall chemo-mechanical coupling efficiency of ATP synthesis. Consistent with this, it was previously reported that the coupling efficiency of ATP synthesis on F1 during the forcible reverse rotation at 10 Hz was enhanced by almost fivefold when F1 was reconstituted with the ε subunit (31).

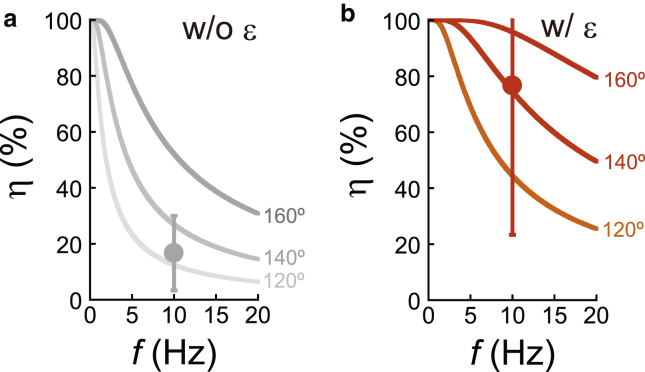

Here, we quantitatively estimated how the ε subunit enhances the probability of ATP release (η) during the forcible reverse rotation of F1, using the determined angle dependence of koffATP in the presence of the ε subunit (Fig. 7). The calculation is similar to our previous numerical analysis of the ATP-binding probability upon forcible forward rotation (42). In this calculation, we assume that F1 has a chance to release bound ATP until γ reaches 120–160° in the clockwise direction (synthesis direction) from the ATP-binding angle. This assumption is based on the observation that the catalytic site again enhances the affinity toward ATP or ADP from −160° to −120° (200–240° in Fig. 1 b) (20, 43). Hereafter, the maximum angle displacement from the ATP-binding angle where F1 can release ATP is expressed as θoff. When the forcible rotation is considered as a stepwise rotation with a step size of Δθ, the probability that F1 releases ATP at θ is expressed as poff(θ) = 1 − exp(−koffATP(θ)·Δt), where koffATP(θ) is the angle dependence of koffATP determined in this study; koffATP(θ) = 0.12 × exp(−0.043·θ) and 0.58 × exp(−0.042·θ) for F1−ε and F1+ε, respectively (Fig. 3 d); and Δt is the step duration at f Hz rotation; Δt = Δθ/(360·f). The coupling efficiency (η) is accordingly expressed as η = , where koffATP(θ) is given as koffATP(θ) = koffATP(0°) × exp(−α·θ). The solid lines in Fig. 7 represent the calculated coupling efficiencies (η) for F1−ε and F1+ε at θoff = 120, 140, and 160, which were markedly enhanced by incorporation with the ε subunit from 13–52 to 45–96% for F1−ε and F1+ε at f = 10 Hz. We previously reported that the ε subunit enhanced the net efficiency of ATP synthesis from 17 ± 13% to 77 ± 53% when the γ subunit was forcibly rotated in the clockwise direction at 10 Hz (31). Thus, the numerical estimation based on this study well explains our previous ATP synthesis experiment with the ε subunit. We further note that the maximum rate of ATP synthesis for thermophilic FoF1 at room temperature was biochemically determined to be ∼30 ATP molecules s−1 (44), which corresponds to ∼10 Hz rotation of the γ subunit, assuming that the rotation and catalysis are tightly coupled. Our result therefore implies that the enhancement of ATP release by the ε subunit is critical for the maximum ATP synthesis activity.

Figure 7.

Chemo-mechanical coupling efficiency during ATP synthesis. (a) The coupling efficiency of forcible rotation with ATP release in the absence of the ε subunit. The gray lines represent the results of numerical calculation based on koffATP(θ) = 0.12 × exp(−0.043·θ) determined for F1−ε in Fig. 3d at θoff = 120° (light gray), 140° (gray), and 160° (thick gray). The gray circle represents the net coupling efficiency of F1−ε during ATP synthesis, as experimentally determined in the previous study (31). (b) The coupling efficiency of forcible rotation with ATP release in the presence of the ε subunit. The colored lines represent the results of numerical calculation based on koffATP(θ) = 0.58 × exp(−0.042·θ) determined for F1+ε in Fig. 3 d at θoff = 120° (orange), 140° (pink), and 160° (red). The red circle represents the net coupling efficiency of F1+ε as determined in the previous study (31). w/o, without; w/, with. To see this figure in color, go online.

This study determined the equilibrium constants of ATP binding/release and hydrolysis/synthesis as the function of the rotary angle (Figs. 3 e and 4 e). As previously reported, the slopes of the equilibrium constants reflect the magnitude of torque generated upon each reaction step, N ∝ dΔG(θ)/dθ = kBT·[ln(KE(θ))], where N represents the generated torque (38, 45). These results show that kBT·[ln(KE(θ))] for the ATP-binding or hydrolysis process is not different between F1−ε and F1+ε, whereas koff or ksyn was enhanced in the presence of the ε subunit. This suggests that the ε subunit does not affect torque generation, which is consistent with the previous report (46). For further understanding, direct measurement of the thermodynamic efficiency of F1+ε using single molecule manipulation is awaited in future studies (18, 47).

The chemo-mechanical coupling of F1 is mediated via interfaces between rotor and stator subunits (9, 48, 49, 50). It was revealed that when the rotor-stator interface is engineered and the resultant rotary potential of the rotor in the stator ring is largely affected (38, 51), the rate and equilibrium constants of catalysis are also significantly modulated (52, 53). Considering these reports, one possible molecular mechanism of the ε-assisted kinetic modulation of ATP binding and synthesis is the enhancement of rotor stiffness by the ε subunit, which presumably improves the chemo-mechanical coupling efficiency via rotor-stator interactions by the enhancement of rotary potential. Although the comparison of rotary potentials between F1−ε and F1+ε (Fig. S4) did not support this explanation, we consider that this possibility is not completely excluded as our analysis might not be sensitive enough to detect a subtle change in the stiffness or the rotary potential. We note that the apparent rotary fluctuation should include not only the rotary diffusion or the stiffness of the rotor in the stator ring, but also the rotary fluctuation of the whole F1 molecule owing to the flexible His-tag linkers. On the other hand, chloroplast F1 may provide some insights regarding this issue. It is known that F1 from chloroplast or photosynthetic bacteria significantly modulates the catalytic activity of hydrolysis or synthesis upon disulphide bond formation or cleavage between two intrinsic cysteines of the γ subunit (54, 55, 56). However, because the cysteine residues are located at the distal part from the stator-ring interface, how the disulphide bond formation can affect the catalytic activity remains elusive (54).

A possible role of the C-terminal domain in the observed ε subunit-associated ATP release and synthesis rate enhancement may be considered because it is well recognized that the ε subunit C-terminal domain blocks ATP hydrolysis and resultant rotation by extending into the cleft between the γ subunit and the stator ring (27, 28). However, it should be emphasized that the ε subunit should not assume the inhibitory extended state under our experimental conditions, because we selectively investigated only the actively rotating molecules. In addition, it should be noted that the noninhibitory state of the ε subunit should be very stable within the observation time according to the previous kinetic analysis of the conformational transition of the ε subunit from TF1 (33). Thus, the extended state of the C-terminal domain of the ε subunit is unlikely to be involved in the observed rate enhancement. Consistent with this argument, the mutant ε subunit from which the C-terminal domain was truncated exhibited similar rate constant enhancement as observed for the intact ε subunit.

F1 frequently lapses into MgADP inhibition, a common feature of F1-ATPases from various species. We previously proposed the following reaction scheme for ADP inhibition: TF1 lapses into the MgADP inhibited form when Pi or Thio-Pi, which should be released at around 320° during active turnover, are occasionally released before ADP release at around 240° (57). These results showed that the ε subunit suppresses the occasional release of Thio-Pi release at around 200° by almost fourfold. This finding is suitably consistent with the previous biochemical study that the MgADP inhibition of TF1 was suppressed by incorporation with a truncated ε subunit (εΔc) (39). The effect of the ε subunit on MgADP inhibition is different among species (58) and, therefore, single-molecule analysis for other species would help to understand the universal principle underlying the mechanism of MgADP inhibition.

In vivo, F1 forms FoF1-ATP synthase and synthesizes ATP by coupling with a rotary motion driven by Fo. Recently, the rotary motion and proton translocation of the FoF1 complex on a lipid bilayer membrane was visualized at the single-molecule level (7, 8, 59). For further understanding of the effect of the ε subunit on catalysis at physiological conditions, verification by single-molecule measurement of the FoF1 complex is desirable in the future.

Author Contributions

R.W. and M.G. designed and performed experiments and analyzed data. Y. K. provided technical support. H.N. designed experiments. H.N. and R.W wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (JP15H05591) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, by a PRESTO grant (JPMJPR13LC) from the Japan Science and Technology Agency, and by a research grant from the Nagase Science Technology Foundation (to R.W.).

Editor: Kazuhiro Oiwa.

Footnotes

Four figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)31211-0.

Contributor Information

Rikiya Watanabe, Email: wrikiya@nojilab.t.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Hiroyuki Noji, Email: hnoji@appchem.t.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Yoshida M., Muneyuki E., Hisabori T. ATP synthase--a marvellous rotary engine of the cell. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:669–677. doi: 10.1038/35089509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Junge W., Sielaff H., Engelbrecht S. Torque generation and elastic power transmission in the rotary F(O)F(1)-ATPase. Nature. 2009;459:364–370. doi: 10.1038/nature08145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber J. Structural biology: toward the ATP synthase mechanism. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:794–795. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noji H., Ueno H., McMillan D.G.G. Catalytic robustness and torque generation of the F1-ATPase. Biophys. Rev. 2017;9:103–118. doi: 10.1007/s12551-017-0262-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukherjee S., Warshel A. The FOF1 ATP synthase: from atomistic three-dimensional structure to the rotary-chemical function. Photosynth. Res. 2017;134:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11120-017-0411-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morales-Rios E., Montgomery M.G., Walker J.E. Structure of ATP synthase from Paracoccus denitrificans determined by X-ray crystallography at 4.0 Å resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:13231–13236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517542112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe R., Tabata K.V., Noji H. Biased Brownian stepping rotation of FoF1-ATP synthase driven by proton motive force. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1631. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diez M., Zimmermann B., Gräber P. Proton-powered subunit rotation in single membrane-bound F0F1-ATP synthase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nsmb718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrahams J.P., Leslie A.G., Walker J.E. Structure at 2.8 A resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Nature. 1994;370:621–628. doi: 10.1038/370621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cingolani G., Duncan T.M. Structure of the ATP synthase catalytic complex (F(1)) from Escherichia coli in an autoinhibited conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2011;18:701–707. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kabaleeswaran V., Puri N., Mueller D.M. Novel features of the rotary catalytic mechanism revealed in the structure of yeast F1 ATPase. EMBO J. 2006;25:5433–5442. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noji H., Yasuda R., Kinosita K., Jr. Direct observation of the rotation of F1-ATPase. Nature. 1997;386:299–302. doi: 10.1038/386299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masaike T., Koyama-Horibe F., Nishizaka T. Cooperative three-step motions in catalytic subunits of F(1)-ATPase correlate with 80 degrees and 40 degrees substep rotations. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:1326–1333. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasuda R., Noji H., Yoshida M. F1-ATPase is a highly efficient molecular motor that rotates with discrete 120 degree steps. Cell. 1998;93:1117–1124. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spetzler D., Ishmukhametov R., Frasch W.D. Single molecule measurements of F1-ATPase reveal an interdependence between the power stroke and the dwell duration. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7979–7985. doi: 10.1021/bi9008215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cherepanov D.A., Junge W. Viscoelastic dynamics of actin filaments coupled to rotary F-ATPase: curvature as an indicator of the torque. Biophys. J. 2001;81:1234–1244. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75781-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bilyard T., Nakanishi-Matsui M., Berry R.M. High-resolution single-molecule characterization of the enzymatic states in Escherichia coli F1-ATPase. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2012;368:20120023. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toyabe S., Watanabe-Nakayama T., Muneyuki E. Thermodynamic efficiency and mechanochemical coupling of F1-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:17951–17956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106787108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe R., Noji H. Chemomechanical coupling mechanism of F(1)-ATPase: catalysis and torque generation. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1030–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe R., Iino R., Noji H. Phosphate release in F1-ATPase catalytic cycle follows ADP release. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:814–820. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimabukuro K., Yasuda R., Yoshida M. Catalysis and rotation of F1 motor: cleavage of ATP at the catalytic site occurs in 1 ms before 40 degree substep rotation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:14731–14736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434983100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasuda R., Noji H., Itoh H. Resolution of distinct rotational substeps by submillisecond kinetic analysis of F1-ATPase. Nature. 2001;410:898–904. doi: 10.1038/35073513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ariga T., Muneyuki E., Yoshida M. F1-ATPase rotates by an asymmetric, sequential mechanism using all three catalytic subunits. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adachi K., Oiwa K., Kinosita K., Jr. Coupling of rotation and catalysis in F(1)-ATPase revealed by single-molecule imaging and manipulation. Cell. 2007;130:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishizaka T., Oiwa K., Kinosita K., Jr. Chemomechanical coupling in F1-ATPase revealed by simultaneous observation of nucleotide kinetics and rotation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:142–148. doi: 10.1038/nsmb721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krah A. Linking structural features from mitochondrial and bacterial F-type ATP synthases to their distinct mechanisms of ATPase inhibition. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2015;119:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shirakihara Y., Shiratori A., Suzuki T. Structure of a thermophilic F1-ATPase inhibited by an ε-subunit: deeper insight into the ε-inhibition mechanism. FEBS J. 2015;282:2895–2913. doi: 10.1111/febs.13329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber J., Dunn S.D., Senior A.E. Effect of the epsilon-subunit on nucleotide binding to Escherichia coli F1-ATPase catalytic sites. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:19124–19128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato Y., Matsui T., Yoshida M. Thermophilic F1-ATPase is activated without dissociation of an endogenous inhibitor, epsilon subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:24906–24912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cipriano D.J., Dunn S.D. The role of the epsilon subunit in the Escherichia coli ATP synthase. The C-terminal domain is required for efficient energy coupling. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:501–507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509986200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rondelez Y., Tresset G., Noji H. Highly coupled ATP synthesis by F1-ATPase single molecules. Nature. 2005;433:773–777. doi: 10.1038/nature03277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uhlin U., Cox G.B., Guss J.M. Crystal structure of the epsilon subunit of the proton-translocating ATP synthase from Escherichia coli. Structure. 1997;5:1219–1230. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iino R., Murakami T., Yoshida M. Real-time monitoring of conformational dynamics of the epsilon subunit in F1-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:40130–40134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506160200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saita E., Iino R., Yoshida M. Activation and stiffness of the inhibited states of F1-ATPase probed by single-molecule manipulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:11411–11417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.099143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirono-Hara Y., Ishizuka K., Noji H. Activation of pausing F1 motor by external force. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:4288–4293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406486102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe R., Okuno D., Noji H. Mechanical modulation of catalytic power on F1-ATPase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;8:86–92. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iizuka S., Kato S., Kato-Yamada Y. gammaepsilon Sub-complex of thermophilic ATP synthase has the ability to bind ATP. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;349:1368–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watanabe R., Koyasu K., Noji H. Torque transmission mechanism via DELSEED loop of F1-ATPase. Biophys. J. 2015;108:1144–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kato-Yamada Y., Bald D., Yoshida M. Epsilon subunit, an endogenous inhibitor of bacterial F(1)-ATPase, also inhibits F(0)F(1)-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:33991–33994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.33991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cruz J.A., Harfe B., McCarty R.E. Molecular dissection of the epsilon subunit of the chloroplast ATP synthase of spinach. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:1379–1388. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.4.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyer P.D., Cross R.L., Momsen W. A new concept for energy coupling in oxidative phosphorylation based on a molecular explanation of the oxygen exchange reactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1973;70:2837–2839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.10.2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iko Y., Tabata K.V., Noji H. Acceleration of the ATP-binding rate of F1-ATPase by forcible forward rotation. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3187–3191. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adachi K., Oiwa K., Kinosita K., Jr. Controlled rotation of the F1-ATPase reveals differential and continuous binding changes for ATP synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:1022. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soga N., Kinosita K., Jr., Suzuki T. Kinetic equivalence of transmembrane pH and electrical potential differences in ATP synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:9633–9639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.335356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watanabe R., Noji H. Characterization of the temperature-sensitive reaction of F1-ATPase by using single-molecule manipulation. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4962. doi: 10.1038/srep04962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kato-Yamada Y., Noji H., Yoshida M. Direct observation of the rotation of epsilon subunit in F1-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:19375–19377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saita E., Suzuki T., Yoshida M. Simple mechanism whereby the F1-ATPase motor rotates with near-perfect chemomechanical energy conversion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:9626–9631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422885112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang H., Oster G. Energy transduction in the F1 motor of ATP synthase. Nature. 1998;396:279–282. doi: 10.1038/24409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mukherjee S., Warshel A. Electrostatic origin of the mechanochemical rotary mechanism and the catalytic dwell of F1-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:20550–20555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117024108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mukherjee S., Warshel A. Dissecting the role of the γ-subunit in the rotary-chemical coupling and torque generation of F1-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:2746–2751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500979112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sielaff H., Rennekamp H., Junge W. Domain compliance and elastic power transmission in rotary F(O)F(1)-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:17760–17765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807683105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tanigawara M., Tabata K.V., Noji H. Role of the DELSEED loop in torque transmission of F1-ATPase. Biophys. J. 2012;103:970–978. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Usukura E., Suzuki T., Yoshida M. Torque generation and utilization in motor enzyme F0F1-ATP synthase: half-torque F1 with short-sized pushrod helix and reduced ATP synthesis by half-torque F0F1. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:1884–1891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.305938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim Y., Konno H., Hisabori T. Redox regulation of rotation of the cyanobacterial F1-ATPase containing thiol regulation switch. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:9071–9078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.200584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Evron Y., Johnson E.A., McCarty R.E. Regulation of proton flow and ATP synthesis in chloroplasts. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2000;32:501–506. doi: 10.1023/a:1005669008974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bald D., Noji H., Hisabori T. ATPase activity of a highly stable alpha(3)beta(3)gamma subcomplex of thermophilic F(1) can be regulated by the introduced regulatory region of gamma subunit of chloroplast F(1) J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:12757–12762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watanabe R., Noji H. Timing of inorganic phosphate release modulates the catalytic activity of ATP-driven rotary motor protein. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3486. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shah N.B., Hutcheon M.L., Duncan T.M. F1-ATPase of Escherichia coli: the ε- inhibited state forms after ATP hydrolysis, is distinct from the ADP-inhibited state, and responds dynamically to catalytic site ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:9383–9395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.451583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watanabe R., Soga N., Noji H. Arrayed lipid bilayer chambers allow single-molecule analysis of membrane transporter activity. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4519. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.