Abstract

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) is an oral precancerous condition characterized by inflammation and progressive fibrosis of the submucosal tissues resulting in marked rigidity and trismus. OSMF still remains a dilemma to the clinicians due to elusive pathogenesis and less well-defined classification systems. Over the years, many classification systems have been documented in medical literature based on clinical, histopathological, or functional aspects. However, none of these classifications have achieved universal acceptance. Each classification has its own merits and demerits. An attempt is made to provide and update the knowledge of classification system of OSMF so that it can assist the clinicians, beneficial in researches and academics in categorizing this potentially malignant disease for early detection, prompt management, and reducing the mortality. Along with this, pathogenesis and management have also been discussed.

Keywords: Areca nut, blanching, collagen, fibrosis, oral submucous fibrosis

INTRODUCTION

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) precancerous condition and is chronic, resistant disease characterized by juxta-epithelial inflammatory reaction and progressive fibrosis of the submucosal tissues. In 1966, Pindborg[1] defined OSMF as “an insidious chronic disease affecting any part of the oral cavity and sometimes pharynx. It is associated with juxta-epithelial inflammatory reaction followed by fibroelastic changes in the lamina propria layer, along with epithelial atrophy which leads to rigidity of the oral mucosa proceeding to trismus and difficulty in mouth opening.” Other terms used to describe this condition are juxta-epithelial fibrosis, idiopathic scleroderma of the mouth, idiopathic palatal fibrosis, submucous fibrosis of the palate and pillars, sclerosing stomatitis, and diffuse OSMF.[2]

It occurs at any age but most commonly seen in young and adults between 25 and 35 years (2nd–4th decade). Onset of this disease is insidious and is often 2–5 years of duration. It is commonly prevalent in Southeast Asia and Indian subcontinent.[3] The prevalence rate of OSMF in India is about 0.2%–0.5%. This increased prevalence is due to increased use and popularity of commercially prepared areca nut and tobacco product - gutkha, pan masala, flavored supari, etc.[4] The malignant transformation rate of OSMF was found to be 7.6%.

ETIOPATHOGENESIS

OSMF was first described by Schwartz in 1952, where it was classified as an idiopathic disorder by the term atrophia idiopathica (tropica) mucosae oris.[5] Since then, many hypotheses are being suggested that OSMF is multifactorial in origin with etiological factors are areca nut, capsaicin in chilies, micronutrient deficiencies of iron, zinc, and essential vitamins. Autoimmune etiological basis of disease with demonstration of various autoantibodies with a strong association with specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) antigens has also been suggested.[6]

Areca nut (betel nut) chewing is one of the most common causes of OMSF which contains tannins (11%–12%) and alkaloids such as arecoline, arecaidine, guvacine, and guvacoline (0.15%–0.67%). Out of all arecoline is the main agent. Arecaidine is an active metabolite in fibroblast stimulation and proliferation, thereby inducing collagen synthesis. With the addition of slaked lime (Ca[OH] 2) to areca nut, it causes hydrolysis of arecoline to arecaidine making this agent available in the oral environment. Tannin present in areca nut reduces collagen degradation by inhibiting collagenases. OSMF is induced as a combined effect of tannin and arecoline by the mechanism of reducing degradation and increased production of collagen, respectively.[5]

Nutritional deficiencies

Deficiency of iron (anemia), Vitamin B complex, minerals, and malnutrition are promoting factors that disturbs the repair process of the inflamed oral mucosa, thus leads to deranged healing and resultant scarring and fibrosis. The resulting atrophic oral mucosa is more susceptible to the effects of chilies, betel nuts, and other irritants.[7]

Genetics and immunology

A genetic component is believed to be involvement in OSMF because there are cases reported in medical literature in people without any history of betel nut chewing or chili ingestion. Patients with OSMF have increased frequency of HLA-A10, HLA-B7, and HLA-DR3.[8]

An immunologic phenomenon is thought to play a role in the etiopathogenesis of OSMF. The increase in CD4 cells and cells with HLA-DR in these diseased tissues shows activation of most lymphocytes and increased number of Langerhans cells. These immunocompetent cells and high of CD4:CD8 ratio in OSMF tissues show the activation of cellular immune response which results in deranged immunoregulation and an altered local tissue morphology. These changes may be due to direct stimulation from exogenous antigens such as areca alkaloids or due to changes in tissue antigenicity leading an autoimmune response.[9] The major histocompatibility complex Class I chain-related gene A (MICA), which is expressed by keratinocytes and epithelial cells, interacts with gamma/delta T cells localized in the submucosa. MICA has got a triplet repeat (guanine, thymine, cytosine) polymorphism in the transmembrane domain, which results in five different allelic patterns. The phenotype frequency of allele A6 of MICA is higher in OSMF.[10] Increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and reduced antifibrotic interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) also contribute to the pathogenesis of OSMF.[11]

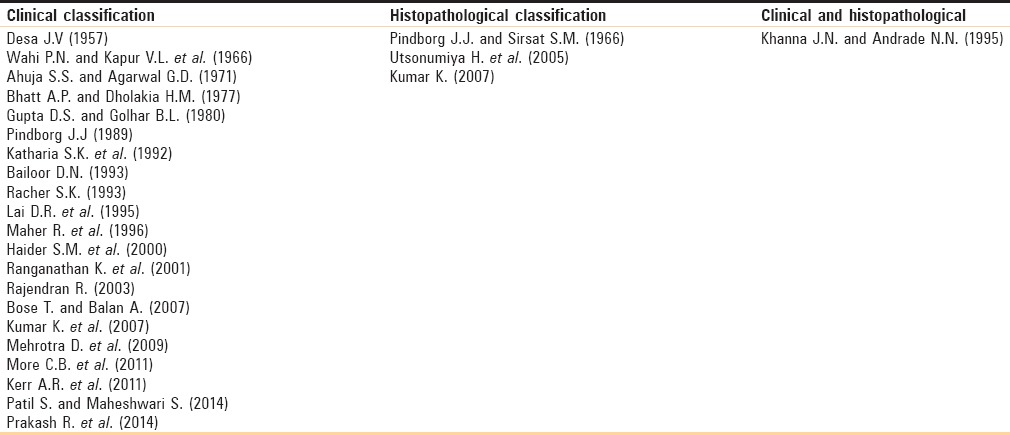

Various staging/grading classification systems have been documented in medical literature by various authors in the past. Some of the staging system is routinely used in the clinical practice and help in early diagnosis and treatment [Table 1].

Table 1.

Different classification, staging, and grading systems

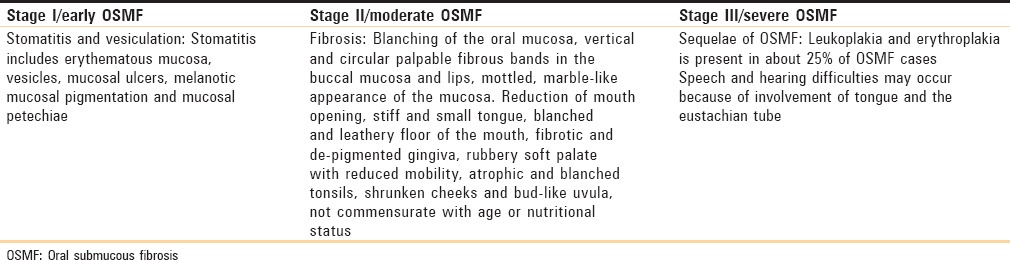

This classification system is based on clinical presentation and progression of the disease only.[12] It has not pointed any functional component (mouth opening), histological component treatment, and prognosis [Table 2].

Table 2.

Clinical staging/classification

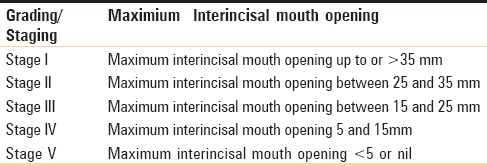

This classification system is based on the functional component.[12] Although commonly used, this classification has not highlighted clinical features, histological features, treatment, and prognosis [Table 3].

Table 3.

Functional staging/classification: Based on mouth opening between upper and lower central incisors

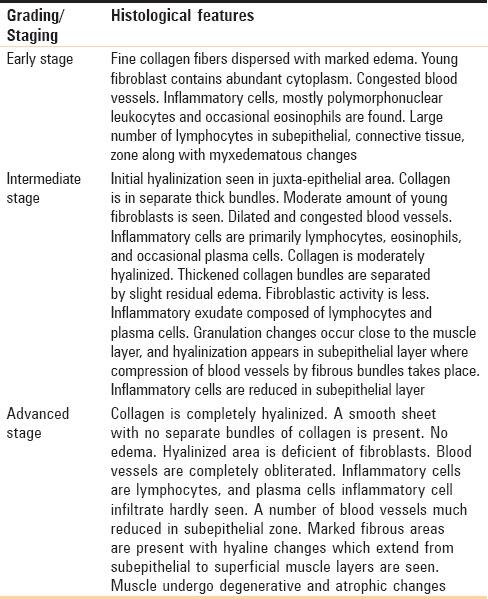

This classification system is based on the histological features of the disease only.[12] No clinical part, functional component, treatment, and prognosis are discussed [Table 4].

Table 4.

Histopathological staging/classification

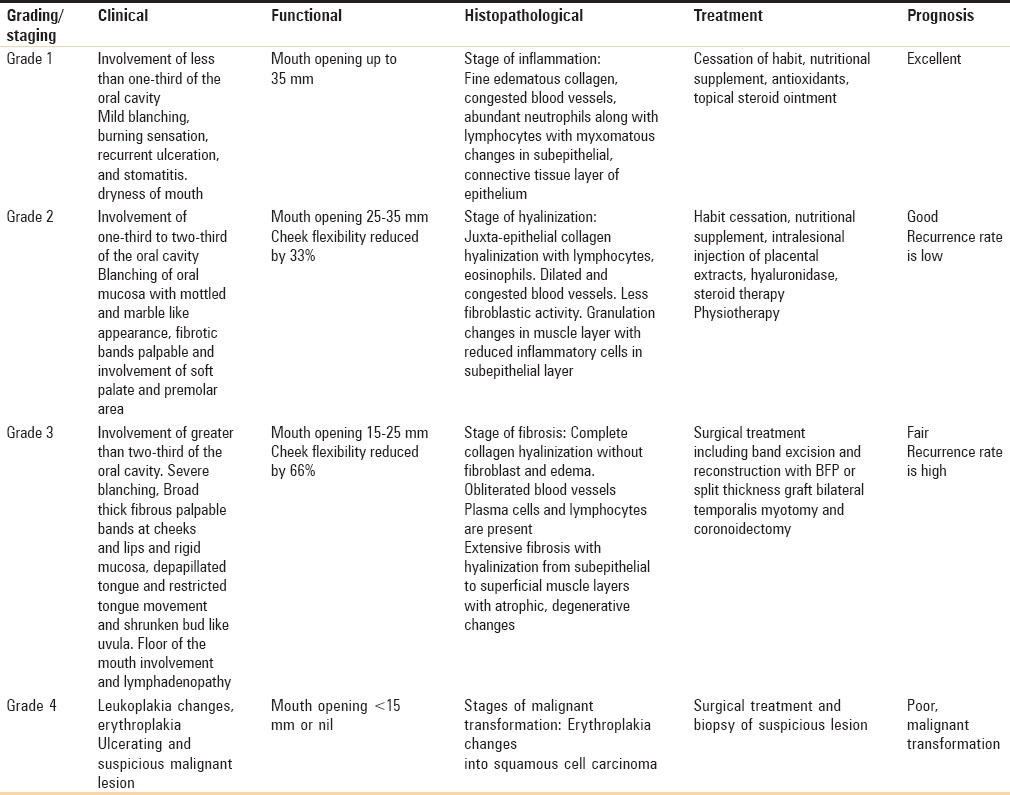

This classification system includes all the parameters/component of OSMF such as clinical features, histopathological features, functional component, treatment part, and prognosis [Table 5]. None of the previous classifications have included all these features in one classification. The main drawback of this classification is that it is bit complex and lengthy to read.

Table 5.

Classification of oral submucous fibrosis: Passi D et al. (2017)

Treatment of oral submucous fibrosis

The treatment of OSMF depends on the degree of disease progression and clinical involvement. At early stages, stopping habit and nutritional supplements are done. At moderate stages, conservative treatment such as intralesional injections along with medical treatment is provided. At advanced stages, surgical interventions are needed.

Cessation of habit

The stoppage of habit such as betel quid, areca nut and other local irritants, spicy and hot food, alcohol, and smoking through education and patient motivation. All affected patients should be educated and warned about the possible malignant transformation.

Supplementary care

Diet rich in iron, vitamins, and minerals should be advised to patients with OSMF. Deficiency of iron plays important role in both etiology and pathogenesis of OSMF. Hence, routine hemoglobin level should be monitored along with iron supplements should be given in diet.[5] Vitamin B deficiency plays an important role in the etiology of degenerative changes in oral mucosa before malignant transformation. Vitamin B complex supplement may relieve glossitis, inflammation of tongue, and cheilosis in OSMF patients.[13]

Antioxidants

Carotenoids (lycopene) induce stimulation of immune system or direct action in tumor cells. Lycopene inhibits hepatic fibrosis genes in LEC rats and also exerts a similar inhibition on the abnormal fibroblasts in OSMF.[14]

Steroid therapy, placental extracts, and chymotrypsin

Steroids → reduction of proliferation of fibroblasts → a number of collagen fibers decreases. Steroids release cellular proteases enzymes in extracellular compartment in connective tissues → activation of collagen and zymogens → ingestion of insoluble collagen → collagen breakdown stimulation.

Steroids also act by reducing inflammatory response. Steroid ointment and intralesional dexamethasone injection are generally used. Placentrex is an aqueous extract of human placenta having nucleotides, enzymes, steroids, vitamins, and amino acids. It acts by biogenic stimulation. It is injected into the body after resistance to pathogenic factors and stimulates the metabolic or regenerative processes. Chymotrypsin is an endopeptidase enzyme which causes hydrolysis of ester and peptide bonds and hence acts as proteolytic and anti-inflammatory agent.[15]

Hyaluronidase

It acts by breaking down hyaluronic acid, lowers the viscosity of intracellular substances, and decreases collagen formation. It produces burning sensation and trismus. Combination of steroids and hyaluronidase shows better long-term results than either used alone.[16]

Pentoxifylline

Pentoxifylline is a tri substituted methyl methylxanithine derivative. It is a rheological modifier; it improves microcirculation and decreased platelet aggregation as well as granulocyte adhesion and also has good improvement in radiation-induced superficial fibrotic lesions of skin and direct effect on inhibiting burn scar fibroblasts. It has also been used to alleviate the symptoms in patients with OSMF.[17]

Interferon-gamma

It has immino-regulatory effect. It is also known as antifibrotic cytokine, patients treated with an intralesional injection of IFN-gamma experienced improvement of symptoms.[18]

Immune milk

Immune milk consists anti-inflammatory component which suppresses the inflammatory process and stimulates the cytokine production. Good symptomatic relief in OSMF patients is due to micronutrients in the immune milk powder.[19]

Turmeric

Turmeric powder provides benzopyrene-induced stimulated production of micronuclei in circulating lymphocytes. It also acts as an excellent scavenger of free radical. Turmeric oil and turmeric resin both act synergistically to protect against DNA damage.[20]

Physiotherapy

Muscle stretching exercises for the mouth are helpful in preventing further reduction in mouth opening. Forceful jaw opening exercise is with mouth gag or heisters jaw opener.

Diathermy, ultrasound, lasers: Microwave diathermy

Microwave diathermy acts by physio-fibrinolysis of fibrous bands through selective heating of juxta-epithelial connective tissue. Ultrasound has a role in deep heating modality. It's selectivity raises the temperature in accumulated areas. CO2 laser techniques involve multiple small incisions which provide surgical relief of restricted oral aperture because the laser beam seals all the blood vessels, thus allowing the surgeon a perfect visibility and accuracy in fibrous band excision.[21]

Cryosurgery

It is the method of locally destroying the abnormal tissue by freezing it in situ and applying liquid nitrogen or argon gas.[22]

Surgical treatment

In patients with severe trismus, surgical intervention is done which includes simple excision of fibrotic bands with reconstruction using buccal fat pad and split thickness graft along with temporalis myotomy and coronoidectomy. The surgery is performed under general anesthesia. The intubation is difficult due to restricted mouth opening. Endotracheal intubation under deep inhalational anesthesia or using muscle relaxants with regional block is preferred. Fiber-optic guided intubation techniques have also been used.

CONCLUSION

OSMF is a premalignant condition and is enigma to maxillofacial surgeon for its chronic, progressive, recurrent, and malignant transformation potential. An attempt is made by us to update the knowledge of the recent developments that enhances the understanding of the etiology of this premalignant condition and its medicinal and surgical management which improves the life expectancy. Furthermore, a newer classification is derived which provides all the components of OSMF functional, clinical, histopathological, treatment, and prognostic component.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pindborg JJ. Oral submucous fibrosis as a precancerous condition. J Dent Res. 1966;45:546–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1984.tb00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prabhu SR, Wilson DF, Daftary DK, Johnson NW. Oral Diseases in the Tropics. New York, Toronto: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 417–22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sabarinath B, Sriram G, Saraswathi TR, Sivapathasundharam B. Immunohistochemical evaluation of mast cells and vascular endothelial proliferation in oral submucous fibrosis. Indian J Dent Res. 2011;22:116–21. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.80009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.More CB, Das S, Patel H, Adalja C, Kamatchi V, Venkatesh R. Proposed clinical classification for oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:200–2. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tilakaratne WM, Klinikowski MF, Saku T, Peters TJ, Warnakulasuriya S. Oral submucous fibrosis: Review on aetiology and pathogenesis. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:561–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajalalitha P, Vali S. Molecular pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis-A collagen metabolic disorder. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:321–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aziz SR. Oral submucous fibrosis: An unusual disease. J N J Dent Assoc. 1997;68:17–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajendran R, Deepthi K, Nooh N, Anil S. A4ß1 integrin-dependent cell sorting dictates T-cell recruitment in oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011;15:272–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.86678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9.Haque MF, Harris M, Meghji S, Speight PM. An immunohistochemical study of oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 1997;26:75–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1997.tb00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu CJ, Lee YJ, Chang KW, Shih YN, Liu HF, Dang CW. Polymorphism of the MICA gene and risk for oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haque MF, Meghji S, Khitab U, Harris M. Oral submucous fibrosis patients have altered levels of cytokine production. J Oral Pathol Med. 2000;29:123–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2000.290304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rangnathan K, Mishra G. An overview of classification schemes for oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2006;10:55–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin H, Koop EC. Precancerous mouth lesions of avitaminosis B; their etiology, response to therapy and relationship to oral cancer. Am J Surg. 1942;57:195. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar A, Bagewadi A, Keluskar V, Singh M. Efficacy of lycopene in the management of oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavina T, Anjana B, Vaishali K. Haemoglobin levels in patients with oral submucous fibrosis. JIAOMR. 2007;19:329–33. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakar PK, Puri RK, Venkatachalam VP. Oral submucous fibrosis-treatment with hyalase. J Laryngol Otol. 1985;99:57–9. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100096286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajendran R, Rani V, Shaikh S. Pentoxifylline therapy: A new adjunct in the treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Indian J Dent Res. 2006;17:190–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.29865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haque MF, Meghji S, Nazir R, Harris M. Interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) may reverse oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:12–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.300103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tai YS, Liu BY, Wang JT, Sun A, Kwan HW, Chiang CP. Oral administration of milk from cows immunised with human intestinal bacteria leads to significant improvements of symptoms and signs in patients with oral sub mucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:618–25. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.301007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hastak K, Lubri N, Jakhi SD, More C, John A, Ghaisas SD, et al. Effect of turmeric oil and turmeric oleoresin on cytogenetic damage in patients suffering from oral submucous fibrosis. Cancer Lett. 1997;116:265–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bierman W. Ultrasound in the treatment of scars. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1954;35:209–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frame JW. Carbon dioxide laser surgery for benign oral lesions. Br Dent J. 1985;158:125–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4805545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]