Abstract

Objective

Our previous randomized controlled trial found that nutrition psychoeducation (NP), an attention-control condition, produced statistically significantly more weight loss than usual care (UC), whereas motivational interviewing (MI) did not. NP, MI, and UC resulted in medium-large, medium, and negligible effects on weight loss, respectively. To examine whether weight loss could be further improved by combining MI and NP, the current study evaluated the scalable combination (MINP) with accessible web-based materials.

Methods

31 adults with overweight/obesity, with and without binge-eating disorder (BED), were enrolled in the 3-month MINP treatment in primary care. Participants were assessed at baseline, post, and 3-month follow-up. Mixed-model analyses examined MINP effects over time and the prognostic significance of BED.

Results

Mixed-model analyses revealed that percentage weight loss was statistically significant at post and 3-month follow-up; d′ =0.59 and 0.53, respectively. BED status did not predict or moderate weight loss. Twenty-one percent (6 of 28) and 26% (7 of 27) of participants attained 5% weight loss by post-treatment and 3-month follow-up, respectively. Participants with BED had statistically significantly greater improvements in disordered eating and depression (in addition to binge-eating reductions) compared to those without BED.

Conclusion

MINP resulted in weight and psychological improvements at post-treatment and through 3-months after treatment completion. There did not appear to be additional benefits to combining basic nutrition information with MI when compared to the previous randomized controlled trial testing nutrition psychoeducation alone.

Keywords: obesity, treatment, motivational interviewing, primary care, binge eating, internet

Introduction

Obesity is a prevalent and costly health problem (1) related to increased risk of early death, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, stroke (2, 3), cancer (4), and dementia (5). This insidious public health issue impacts men and women of all races and ages, (1) and the potential consequences of the obesity epidemic cannot be overstated. To manage the public health challenge that obesity poses, developing weight loss treatments that can be broadly disseminated is critically important (6). For instance, overweight and obesity interventions within primary care offices are a focus of much recent research (7). Of potential interest to busy primary care centers is Motivational Interviewing (MI) for weight loss. MI is an evidence-based, time limited, person-centered counseling approach for strengthening a person’s motivation and commitment to behavior change (8). Fortunately, MI addresses many barriers to providing weight loss treatment in primary care, which include limited time, resources, and training (9, 10), and MI can be implemented effectively by general medical practitioners to treat health-related behavioral concerns (11).

In general, evidence supports the use of MI for weight loss in primary care (12). A recent review of the literature suggested that MI for weight loss interventions incorporating additional support via technology (i.e., computer materials, internet, and/or emails) may further improve weight loss outcomes (12–19). Relatively few studies of MI for weight loss in primary care, however, incorporated such technology. Further, when technology was used, it typically involved computer programs/websites that were not easily or financially accessible to primary care centers. In addition, studies of MI for weight loss in primary care mostly utilized MI clinicians such as dieticians, a resource that may not be readily available in typical primary care centers. These studies also limited recruitment to individuals with obesity only. Due to individuals’ tendency to gain weight annually, (20–23) it is important to include those with obesity and overweight. Further, follow-up assessments were limited to immediately post treatment and did not assess weight loss after a period of treatment cessation, and MI compliance and treatment-fidelity were not included in the studies. Moreover, no studies compared MI to a non-MI attention-control condition, disallowing conclusions about MI’s superiority to other primary care weight loss interventions.

Finally, the role that binge-eating disorder (BED) may play in MI for weight loss in primary care settings has not been sufficiently examined in existing studies. BED is common within primary care, particularly among weight-loss treatment seeking individuals, (19) associated strongly with excess weight and poor health-related outcomes, (24) and may negatively impact weight loss treatment outcomes (25). To our knowledge, only one MI for weight loss in primary care study examined the impact of a BED diagnosis (19) and found no relationship between BED status and weight loss outcomes. Nonetheless, given the possibility that a BED diagnosis may diminish weight loss outcomes when using MI, more work needs to occur in this area.

To address these limitations, we designed and conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) with medical assistants as clinicians, recruited individuals with both overweight and obesity, utilized technology and supporting materials that any primary care provider could easily and currently access, thoroughly assessed for and randomized based on presence of BED, systematically evaluated MI implementation, and included 3- and 12-month follow-up assessments (19, 26). In addition to comparing MI to usual care (i.e., participants attending appointments with their primary care provider as they would have prior to enrollment), we included a nutrition psychoeducation intervention designed as an attention-control comparison condition (19). The attention-control condition (nutrition psychoeducation) included basic nutrition information (e.g., how to read nutrition label, healthy sources of protein and carbohydrates) provided by medical assistants (different medical assistants from those providing MI). Discussing goal setting or behavioral changes during attention-control sessions was proscribed; independent fidelity assessment showed that MI elements were not evident in nutrition psychoeducation sessions (19). The interventions were designed to be scalable and brief (approximately 2 hours and 20 minutes total over 12 weeks). The MI-only intervention did not result in superior weight loss compared to usual care, however, the nutrition psychoeducation intervention led to significantly more weight loss compared to usual care. The weight loss Cohen’s d′ effect sizes for these scalable weight loss interventions in primary care were considered medium (d′ = 0.54), medium-large (d′ = 0.77), and small (d′ = 0.07) for the MI-only, nutrition psychoeducation (attention-control) only, and usual care, respectively. Both MI-only and nutrition psychoeducation, however, resulted in approximately 25% of participants maintaining/achieving 5% weight loss by the 3-month follow-up assessment. In addition to superior weight loss, the nutrition psychoeducation condition also resulted in decreased triglycerides and depression when compared to usual care.

Based on the previous literature and the Barnes and colleague (2014) results, we designed the current follow-up study to test if combining MI and nutrition psychoeducation may bolster the promising outcomes (19). The current trial tested a weight loss intervention in primary care matched for attention to the previously published trial, allowing for comparison of MI plus nutrition psychoeducation with dismantled MI-only and nutritional psychoeducation only. It is important to test this combination as one cannot assume that “more is better” for many reasons. Interventions in primary care need to be time limited, so it was unclear if interventionists could provide MI and nutrition psychoeducation within the same time frame as they previously provided just one or the other. Additionally, it is possible that psychoeducation could be delivered in a manner at odds with MI. MI relies on the individuals’ interests/desires, rather than providing unsolicited information as in psychoeducation. We tested if medical assistants could provide MI-consistent treatment while including nutrition psychoeducation. We followed the same recruitment procedures and eligibility requirements and we monitored enrollment on several demographic variables (i.e., sex, race, age, body mass index, and BED status) to ensure a highly similar participant group. We hypothesized that the MI plus nutrition psychoeducation weight loss trial in primary care would result in significant decreases in weight, and related physiological and psychological improvements.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were 31 adults (body mass index [BMI] between 25–55) with overweight or obesity receiving primary care services at an urban university-based medical healthcare center. They were recruited through primary care provider referrals and flyers placed in waiting/patient rooms. Recruitment continued until the current enrolled sample size was like the previous trial (n = 30 per condition) and current participants’ demographics did not differ significantly from those in the previous trial (19). Recruitment was intended to enhance generalizability by utilizing relatively few exclusionary criteria. Exclusion criteria included over 65 years old, severe psychiatric (e.g., schizophrenia) or medical problems (e.g., cardiac disease), pregnancy/breastfeeding, or uncontrolled liver, thyroid disease, hypertension, or diabetes. The Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) (27) was used to exclude individuals with cardiovascular problems, chest pains, and unexplained/frequency dizziness. Participants endorsing high blood pressure, physical conditions that may prohibit physical activity, or explainable/infrequent dizziness were required to obtain primary care provider consent to participate. Participants were required to have regular internet and telephone access.

Measures

The Eating Disorder Examination (EDE)

The Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) (28), a semi-structured interview for assessing eating disorders including BED, has demonstrated good inter-rater and test-retest reliability with samples of individuals with BED (29, 30). The EDE-Global score provides an overall index of eating disorder symptomatology, with higher scores reflecting greater severity. The EDE also assesses frequency of loss of control over eating with both unusually large amounts of food (objective binge-eating episodes) and regular/small amounts of food (subjective binge-eating episodes). For the current analyses, we examined number of days in the past 28 days that the participants reported these episodes.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (31) is a self-report measure of current depression symptoms with higher scores reflecting increased severity; the BDI has excellent reliability and validity (32).

The Autonomous Motivation (AMQ)

The Autonomous Motivation (AMQ) (33) subscale of the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire is a self-report measure of internal/personal reasons for losing weight with satisfactory reliability. Higher scores reflect higher levels of motivation.

Physical Measurements

Height was measured at baseline only using a wall measure. Weight was measured at all assessment points using a large-capacity digital scale. Blood pressure and resting heart rate were measured using automated blood pressure monitors, recorded readings were an average of two measurements obtained in a standardized manner by the clinicians. Waist circumference was measured using the umbilicus as a reference point. Assessments were completed at baseline, mid-treatment (week 6), post-treatment (week 12), and 3-month follow-up (week 24) except for the EDE which was not administered at mid-treatment (week 6). Fasting blood work was drawn and analyzed by Quest Diagnostics at baseline and post only.

Procedures

The study had IRB approval. All participants provided written informed consent. Participants completed the battery of self-report measures. Master- or doctoral-level psychology clinicians trained in eating/weight disorders completed the pretreatment intake assessments using the EDE to diagnose BED (28). Treatment was provided by medical assistants to increase generalizability to generalist primary-care settings. Participants were reimbursed at assessment points, receiving up to $200 total. This trial was designed to be as similar as possible with the previous trial, including the same participant recruitment (method and primary care offices), assessment process, face-to-face intervention time, incentives, and medical assistant qualifications, training, and supervision. It is important to note that different medical assistants were recruited for the current trial to avoid potential treatment contamination from the previous RCT.

Intervention

Motivational Interviewing and Nutrition Psychoeducation (MINP) was a five session, manualized, 3-month intervention. MINP included guidelines to help medical assistants flexibly apply MI with strategies to motivate participants for weight-related behavior change and allowed focus on BED as needed. The first session was an initial 60-minute in-person individual appointment, which focused on enhancing motivation for weight loss and treatment adherence and ending with participants setting self-identified specific weight-related goals. Clinicians interacted with their participants in a nonjudgmental and collaborative fashion, conveying respect, acceptance, and compassion toward them and a stance toward evoking the participants’ motives for change, consistent with an MI style of interaction (8, 34). Use of MI-inconsistent strategies (e.g., confrontation) was proscribed. At the participants’ discretion, the session also included basic nutrition psychoeducation (e.g., recommended fruit/vegetable intake, healthy portion and serving sizes) based on the recommendations of the American Heart Association and United States Department of Agriculture. In addition, they received training in the use of supplemental materials: (1) a free weight loss website (Livestrong.com) and (2) a LEARN manual (35), a readily available, well-researched weight loss manual. Clinicians taught participants to login to Livstrong.com, enter pertinent information (height, weight, age, activity level) and weekly weight loss and physical activity goals. Livestrong.com then provided participants with daily calorie guidelines for attaining their goals. Participants were shown how to track food, weight, and exercise, and to monitor other nutrition related information (e.g., carbohydrate intake), and if participants desired, they received personalized feedback on food journals at subsequent sessions. Following this first appointment, participants received up to four additional 20-minute MINP sessions (in-person at weeks 6, 12, by phone at weeks 3, 9). If participants were interested, each session started with a discussion of the participants’ specific and measurable behavioral weight-loss goals (e.g., walk 30 minutes 3 times a week, track food intake on Livestrong.com 4 days a week) from the previous session and ended with setting new goals, including problem-solving as necessary for when goals were not reached. Clinicians used MI strategies (e.g., reflections, affirmations, change planning) in these sessions to enhance participant motivation to meet weight-related goals (e.g., decreasing calories, increasing fruit/vegetable intake, increasing physical activity) and provided nutrition psychoeducation.

Training Clinicians and Fidelity

The medical assistants did not have prior weight loss treatment or MI training. Four medical assistants attended two eight-hour training sessions conducted by a member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers. Clinicians needed to demonstrate adequate MI and nutrition psychoeducation skills, based on an a priori criterion-level of performance (36, 37), with three mock sessions and one real session, all audio recorded. All treatment sessions were recorded with the additional permission of participants. Clinicians attended 60- to 90-minute group supervision meetings once every three weeks and received rated session feedback based on the Motivational Interviewing Assessment: Supervising Tools for Enhancing Proficiency (MIA-STEP) protocol (37). Two independent research-clinicians were trained to rate treatment adherence. At random, 15 treatment sessions (10% of total sessions) were selected, with all in-person sessions represented (i.e., treatment sessions 1, 3, and 5). For MI, consistent with standardized protocols (36, 37), we used the Independent Tape Rater Scale to judge the degree to which the medical assistants performed MI (table 1) adequately (i.e., strategy present at least three times per session with adequate skill) and avoided MI-inconsistent techniques. Every statement made by the medical assistants was rated from 1 (very poor) “the therapist handled this in an unacceptable, even ‘toxic’ manner” to 7 (excellent) “the therapist demonstrated a high level of excellence and mastery in this area.” Adequate skill (4) was considered “the therapist handled this in a manner characteristic of an ‘average,’ ‘good enough’ therapist.” Raters were provided examples of adequate skill for reference. Clinicians also were rated in their completion (or not) of the nutrition psychoeducation (if the participants were interested).

Table 1.

Rater agreement on adequate performance in the delivery of intervention strategies.

| Number of Sessions Meeting Criterion(15 sessions rated total) | Rater Agreement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Rater 1 | Rater 2 | ||

| MI-Consistent Strategies | |||

|

|

|||

| MI spirit | 15 | 15 | 100% |

| Open questions | 15 | 15 | 100% |

| Reflections | 15 | 15 | 100% |

| Affirmations | 15 | 14 | 93% |

| Fostering collaboration | 15 | 15 | 100% |

| Motivation for change | 13 | 14 | 93% |

| Client-centered discussion & feedback | 8 | 9 | 93% |

| Exploring pros/cons/ambivalence | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| Developing discrepancies | 0 | 0 | 100% |

| Change planning discussion | 15 | 15 | 100% |

| MI-Inconsistent Strategies | |||

|

|

|||

| Unsolicited advice | 0 | 0 | 100% |

| Direct confrontation | 0 | 0 | 100% |

| Asserting authority | 0 | 0 | 100% |

| Nutrition Psychoeducation | |||

|

|

|||

| Provided information about nutrition topic | 15 | 15 | 100% |

Note: MI=Motivational Interviewing. Adequate MI performance criterion = demonstration of the strategy at least 3 times in the session with adequate skill. Sessions were randomly selected for two trained judges to independently rate.

Statistical Analyses

Linear mixed models with time as a within-subjects predictor were used to analyze each outcome. The best-fitting variance-covariance structure was chosen based on information criteria. Pair-wise comparisons between time points were performed post-hoc to determine the nature of main time effects. Rates of achieving 5% weight loss were analyzed across time using a generalized linear model with a logit link function specified and random subject effects. Subjective and objective binge eating outcomes were highly skewed and could not be successfully transformed. Therefore, these non-normal outcomes were analyzed using the nonparametric approach for repeated measures data (38), where the data were first ranked, and then fitted using a mixed effects model with an unstructured variance-covariance matrix and p-values adjusted for ANOVA-type statistics (ATS). Main and interactive effects of BED status were considered in all models.

Results

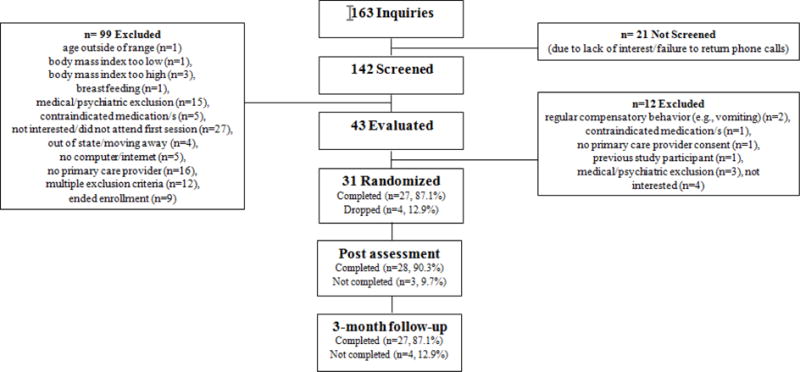

Figure 1 summarizes the flow of study participants. Participant retention was excellent; 87.1%, 90.3%, and 87.1% of participants completed treatment, post-treatment assessment, and 3-month follow-up assessment, respectively. Participants had a mean age of 48.4 years (SD=10.6, range 24–63) and a mean BMI of 36.2 kg/m2 (SD=6.1). The sample was primarily female (87.1%, n=27), and 25.8% (n=8) of participants met DSM-5 BED criteria. Participants were relatively diverse; 41.9% (n=13) of participants identified as White, not Hispanic, 9.7% (n=3) White, Hispanic, 38.7% (n=12) Black, not Hispanic, 3.2% (n=1) bi/multiracial, and 6.5% (n=2) “other.” Participants in this trial did not differ significantly from those enrolled in the previous RCT on the following demographic variables: sex, race, age, body mass index, and BED status (19).

Figure 1.

Participant enrollment.

Treatment Credibility, Satisfaction, Fidelity, and Adherence

Participants completed a five-item treatment credibility measure after randomization, with higher scores indicating more credibility, with possible scores ranging from 5 to 30. The average rating was 25.12 (SD=5.22). Participants completed a seven-item satisfaction measure at post-treatment, with possible scores ranging from 7 to 70 and higher scores reflecting more satisfaction. Participants average satisfaction rating was 65.11 (SD=7.53). Treatment was delivered as intended (see table 1). Eighty-eight percent of participants who were interested in using Livestrong.com at the first session tracked food intake at least once. In the 28 days prior to participants’ post and 3-month follow-up assessments, 48.0% and 16.8% of participants used Livestrong.com to track their food, respectively.

Weight

Overall, percentage weight change from baseline significantly decreased across time (F(2, 51) = 3.97, p = .025) with significant weight loss observed at mid-treatment (t(51) = −2.55, p = .014), post-treatment (t(51) = −3.16, p =.003), and 3-month follow-up (t(51) = −3.07, p =.004). The percentage weight loss at post-treatment ranged from 2.23% gained to −13.17% lost. The percentage weight loss at 3-month follow-up ranged from 3.88% gained to −19.67% lost. An overall main effect of time (x2(2) = 6.29, p=0.043) was observed when analyzing the number of participants reaching 5% weight loss. Compared to the 1 in 28 (3.6%) of participants reaching 5% weight loss by mid-treatment, 6 in 28 (21.4%) and 7 in 27 (25.9%) of participants reached 5% weight loss at post-treatment (x2(1) = 4.75, p = 0.029) and 3-month follow-up (x2(1) = 6.06, p = 0.014), respectively. BED status did not predict or moderate weight loss. Cohen’s d for percentage weight loss (see Table 2) and tabulations of participants reaching 5% weight loss (see Table 3) in the current study are reported for comparison to the previously published RCT that compared MI only to nutrition psychoeducation only and usual care.

Table 2.

Percentage weight loss Cohen’s d′ for the current trial and previous randomized controlled trial (Barnes, White, Martino, & Grilo, 2014).

| Post-treatment (12 weeks) Cohen’s d′ | 3-month follow-up (24 weeks) Cohen’s d′ | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Motivational Interviewing + Nutrition Psychoeducation (current) | 0.59 | 0.53 |

| Barnes and colleagues, 2014 | ||

| Motivational Interviewing | 0.54 | 0.35 |

| Nutrition Psychoeducation | 0.77 | 0.66 |

| Usual Care | 0.07 | 0.01 |

Note. Cohen’s d′ effect size interpretation: 0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, 0.8 = large.

Table 3.

Participants reaching 5% weight loss for the current trial and previous randomized controlled trial (Barnes, White, Martino, & Grilo, 2014).

| Post-treatment (12 weeks) n (%) | 3-month follow-up (24 weeks) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Motivational Interviewing + Nutrition Psychoeducation (current) | 6/28 (21.4) | 7/27 (25.9) |

| Barnes and colleagues 2014 | ||

| Motivational Interviewing | 4/26 (15.4) | 7/26 (26.9) |

| Nutrition Psychoeducation | 5/29 (17.2) | 8/28 (28.6) |

| Usual Care | 2/29 (6.9) | 3/29 (10.3) |

Physical and Metabolic Assessments

Table 4 shows the descriptive data for the physical assessments. Systolic blood pressure decreased significantly across time (F(3, 80) = 2.78, p = .046). Post-hoc analyses showed significant decreases from baseline at both post-treatment (t(80) = 2.04, p = .045) and 3-month follow-up (t(80) = 2.76, p = .007). Similarly, resting heart rate (time effect: F(3, 78)=6.28, p < .001) decreased significantly from baseline at both post-treatment (t(78) = 2.98, p = .004) and 3-month follow-up (t(78) = 3.84, p < .001). Diastolic blood pressure and waist circumference did not change significantly over time. BED status did not predict or moderate changes in physical assessments.

Table 4.

Physical measurement descriptive data.

| Baseline | Mid-treatment (6 weeks) | Post-treatment (12 weeks) | 3-month follow-up (24 weeks) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean |

| Body Mass Index | 31 | 36.2 | 6.1 | 28 | 35.7 | 6.3 | 28 | 35.4 | 6.2 | 27 | 35.0 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | 31 | 85.7 | 7.8 | 28 | 83.1 | 9.1 | 28 | 84.3 | 8.2 | 27 | 81.7 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 31 | 131.5 | 12.4 | 28 | 127.2 | 12.4 | 28 | 126 | 13.9 | 27 | 123.9 |

| Hear Rate | 30 | 78.5 | 10.8 | 27 | 76.4 | 11.9 | 28 | 72.8 | 10.2 | 27 | 70.7 |

| Waist (inches) | 31 | 43.4 | 5.5 | 28 | 42.5 | 5.4 | 28 | 42.5 | 4.5 | 27 | 42.0 |

| Weight (pounds) | 31 | 212.2 | 34 | 28 | 208.9 | 33.7 | 28 | 207.4 | 32.7 | 27 | 204.8 |

Table 5 shows the descriptive data for the metabolic assessments. Fasting lipid profiles (total, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, triglycerides), HbA1c, and glucose did not change significantly between baseline and post-treatment. BED status did not predict or moderate changes in physical assessments.

Table 5.

Metabolic descriptive data.

| Baseline | Post-treatment (12 weeks) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | |

| Glucose | 30 | 129 | 16.7 | 27 | 128 | 15.7 |

| HbA1c | 31 | 5.8 | 0.5 | 27 | 5.8 | 0.4 |

| High-density lipoprotein | 31 | 54.4 | 13.4 | 27 | 53.9 | 13.0 |

| Low-density lipoprotein | 31 | 110.9 | 22.4 | 27 | 111.2 | 20.1 |

| Triglycerides | 31 | 106.9 | 58.3 | 27 | 101.3 | 54.4 |

| Total cholesterol | 31 | 186.7 | 22.4 | 27 | 185.3 | 21.5 |

Psychological and Motivation Assessments

Table 6 shows the descriptive data for the psychological and motivation assessments. Overall eating-disorder psychopathology (EDE-Global) decreased significantly over time (F(2, 53) = 16.36, p < 0.0001). Compared to baseline, the EDE-Global significantly decreased at post-treatment (t(53) = 2.79, p = .007) and 3-month follow-up (t(53) = 5.72, p < 0.0001). When BED status was included in the model, a significant time by BED status interaction (F(2, 51) = 6.36, p = 0.003) was observed. Although significant EDE-Global score decreases were observed in both groups (all p<.005), the interaction was driven primarily by elevated EDE-Global scores among participants with BED at baseline (F(1, 51) = 18.1, p < .0001) and post-treatment (F(1, 51) = 7.3, p = .009), with levels converging to those of participants without BED at 3-month follow-up (F(1, 51) = 0.72, p = .40).

Table 6.

Psychological and motivation descriptive data.

| Baseline | Post-treatment (12 weeks) | 3-month follow-up (24 weeks) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD |

| Eating Disorder Examination-Global | 31 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 28 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 27 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| Objective binge episode days | 31 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 28 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 27 | 0.7 | 2.9 |

| Subjective binge episode days | 31 | 2.7 | 5.8 | 28 | 3.0 | 6.6 | 27 | 0.7 | 2.1 |

| Autonomous Motivation Questionnaire | 31 | 6.8 | 0.4 | 28 | 6.6 | 0.6 | 27 | 6.7 | 0.5 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 31 | 8.7 | 6.5 | 28 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 27 | 5.8 | 5.1 |

Objective binge-eating frequency during the past 28 days (based on the EDE) decreased significantly across time (ATS = 8.31, num df = 1.96, p < .001). Relative to baseline, decreases in objective binge-eating episodes were observed at post-treatment (ATS = 12.8, num df = 1.0, p < .001) and 3-month follow-up (ATS = 10.4, num df = 1.0, p = .001). When BED status was included in the model, a significant time by BED status interaction (ATS = 9.21, num df = 1.96, p < .001) was observed owing to significant overall decreases in objective binge-eating episodes from baseline to post-treatment (ATS = 37.2, num df = 1.0, p < .001) and 3-month follow-up (ATS = 22.0, num df = 1.0, p < .001) among participants with BED, but not among subjects without BED. Similarly, overall significant decreases were observed for subjective binge-eating episodes (based on the EDE) during the past 28 days (ATS = 4.18, num df = 1.77, p = .019). In a separate model including BED status, however, the interaction between time and BED status was not significant (ATS = 1.78, num df = 1.76, p = .17), despite greater subjective binge eating at baseline (ATS = 4.03, num df = 1.0, p = .04) among those with versus those without BED.

There were no overall changes in motivation (AMQ) over time (p = 0.307) and the results did not differ by BED status. Depression symptoms (BDI) decreased significantly across time (F(3,80) = 2.73, p < 0.05) with decreases significant at 6 weeks (t(80) = 2.5, p = 0.015), post-treatment (t(80) = 2.46, p = .016), and 3-month follow-up (t(80) = 2.38, p = 0.020). Including BED diagnosis, however, showed a significant interaction with time (F(3, 77) = 7.0, p < 0.001), owing to significantly higher depression scores at baseline (F(1, 77)=9.92, p = 0.002) among those with BED.

Discussion

A brief and scalable weight loss intervention incorporating MI plus nutrition psychoeducation resulted in statistically significant weight losses for individuals recruited and treated in primary care by generalist medical assistant clinicians. Approximately a quarter of participants (7 of 27) lost/maintained at least 5% of their initial body weight by 3-month follow-up assessment. Medical assistants provided MI alongside nutrition psychoeducation with adequate skill and participants reported high satisfaction with the treatment they received. Weight change and physiological improvements were unrelated to BED status. Depression scores decreased significantly for individuals with BED only, who at baseline had significantly higher depression scores compared to those without BED. Eating disorder psychopathology also decreased significantly over time, with improvements experienced most markedly by individuals with BED. There were no significant motivation changes over time.

Although the current intervention resulted in statistically significant weight loss, the magnitude did not appear to be greater than the weight loss reported for the nutrition psychoeducation-only intervention (attention control) in our previous RCT (19), although obviously comparison across studies is complicated and should be interpreted cautiously. Other than this previous RCT, we are unaware of any other MI for weight loss in primary care studies that tested MI against other specific weight loss treatments beyond usual care/treatment as usual (12). The current initial descriptive comparison may call into question the utility of MI for weight loss in primary care with presumably already motivated treatment-seeking individuals (who in this instance, were also interested and willing to participate in a research study). Scores on the self-report autonomous motivation questionnaire (AMQ) can range from 1 to 7, with higher scores reflecting more motivation. Participants’ average AMQ scores ranged between 6.6 and 6.8 at the three main assessments (baseline, post-treatment, 3-month follow-up), reflecting high levels of desire to participate in the weight loss program. Perhaps these treatment-seeking individuals likely already were committed to weight loss and therefore receptive to nutrition psychoeducation. High AMQ scores, however, do not necessarily translate to behavioral changes and likely there also are other facets of motivation that are differentially related to weight loss outcomes that were not measured in the current trial (39, 40). We do know that the MI in the previous RCT and current trial were provided with adequate skill as reflected in the fidelity monitoring. Moreover, the clinicians providing nutrition psychoeducation-only in the previous trial were not trained in MI and, based on rated nutrition psychoeducation-only sessions, these sessions did not include main MI elements (e.g., intentional efforts to elicit motivations for change, change planning). Additionally, participants were highly satisfied with the current treatment as when they received MI-only or nutrition psychoeducation-only in the previous RCT. The current results require replication in a RCT comparing MI to not only usual care but also other weight loss interventions in primary care before firmer conclusion can be drawn. It is important to understand more specifically the benefits and limitations of MI for weight loss in primary care as the training and supervision to adequately practice MI with patients can be costly.

The current findings add to previous results that the presence of BED is common among patients with overweight/obesity who seek weight loss treatment in primary care settings. Approximately one-quarter of participants met BED criteria. Like the previous RCT, our findings suggest that the presence of BED was unrelated to weight loss outcomes (19, 26, 41). We note that some research has suggested that the presence of BED might dampen obesity treatments with certain medications (i.e., orlistat, 25). Notably, our results did not show this dampening effect on the “behavioral” scalable interventions we tested, which suggests primary care patients with obesity or overweight and BED may not require additional treatment beyond what we offered in our scalable weigh loss interventions. Moreover, brief weight loss interventions involving MI or nutrition education may confer benefits beyond weight loss for this patient population. Compared to those without BED, participants with BED experienced significant declines in depression, eating psychopathology, and objective and subjective binge-eating episodes from baseline to the 3-month follow-up.

It is important to consider the limitations of the current study as context for the findings. This was a small sample with an even smaller number of individuals meeting criteria for BED. While the inclusion/exclusion criteria were meant to be inclusive, the results may not generalize to nontreatment seeking populations or individuals with serious physical or psychological comorbidities. Participants were not randomly assigned to treatment, therefore, there was no direct comparison condition within this trial. Based on other similar trials and the previously published RCT results, participants enrolled in usual care, on average, do not experience significant weight changes (e.g., 14, 19). Similarly, any assumptions based on the comparison of the current trial to the previous RCT need to be made with caution as participants were enrolled into the current treatment whereas they were randomized into the previous RCT treatment.

In conclusion, the current MI plus nutrition psychoeducation weight loss trial in primary care resulted in statistically significant weight losses for individuals with overweight or obesity regardless of BED status. Overall, the current combination trial, however, did not result in additional benefits when descriptively compared to participants receiving nutrition psychoeducation-only in a previous RCT as the effect sizes for the MI plus nutrition psychoeducation were like those for nutrition psychoeducation-only. Considering the resources required for MI, which far exceed those of a basic nutrition psychoeducation, future studies should include a dismantling weight loss RCT within primary care to further clarify the current results.

Highlights.

Brief intervention resulted in statistically significant weight loss in primary care.

Approximately 25% of participants (7/27) reached 5% weight loss by 3-month follow-up.

Weight loss was not superior to previously published nutrition psychoeducation-only.

More research is needed to understand the utility of MI for weight loss in primary care.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by NIH. RDB: R03-DK10400801A1 and K23-DK092279; CMG: K24-DK070052. NIH had no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: RDB, VI, BPP, MP, and SM have no conflicts of interest. CMG reports no relevant conflicts of interest but notes that he has received consultant fees from Shire and Sunovion, honoraria from American Psychological Association, American Academy of CME, Vindico CME, Global Medical Education, Medscape CME, CME Institute of Physicians and Postgraduate Press, and from professional and scientific conferences for lectures and presentations, and book royalties from Guilford Press and Taylor and Francis for academic books.

Clinical Trial Registration: NCT02578199

Competing Interest Statement

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf. RDB, VI, MP BPP, and SM have no conflicts of interest. CMG reports no relevant conflicts of interest but notes that he has received consultant fees from Shire and Sunovion, honoraria from American Psychological Association, American Academy of CME, Vindico CME, Global Medical Education, Medscape CME, CME Institute of Physicians and Postgraduate Press, and from professional and scientific conferences for lectures and presentations, and book royalties from Guilford Press and Taylor and Francis for academic books.

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2012: With Special Feature on Emergency Care. Hyattsville, MD: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001:285. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Jr, Lenfant C, American Heart A et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433–438. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold M, Leitzmann M, Freisling H, Bray F, Romieu I, Renehan A, et al. Obesity and cancer: an update of the global impact. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;41:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedditizi E, Peters R, Beckett N. The risk of overweight/obesity in mid-life and late life for the development of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Age Ageing. 2016;45:14–21. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pagoto SL, Appelhans BM. A call for an end to the diet debates. JAMA. 2013;310:687–688. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.8601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Hong PS, Tsai AG. Behavioral treatment of obesity in patients encountered in primary care settings: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014;312:1779–1791. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. 3rd. New York, NY: Guilford press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai AG, Wadden TA. Treatment of obesity in primary care practice in the United States: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1073–1079. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1042-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Østbye T, Yarnall KS, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Annals Fam Med. 2005;3:209–214. doi: 10.1370/afm.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Söderlund LL, Madson MB, Rubak S, Nilsen P. A systematic review of motivational interviewing training for general health care practitioners. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnes R, Ivezaj V. A systematic review of motivational interviewing for weight loss among adults in primary care. Obesity Reviews. 2015;16:304–318. doi: 10.1111/obr.12264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDoniel SO, Wolskee P, Shen J. Treating obesity with a novel hand-held device, computer software program, and internet technology in primary care: the SMART motivated trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79:185–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett GG, Herring SJ, Puleo E, Stein EK, Emmons KM, Gillman MW. Web-based weight loss in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obesity. 2010;18:308–813. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDoniel SO, Hammond RS. A 24-week randomised controlled trial comparing usual care and metabolic-based diet plans in obese adults. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:1503–1511. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett GG, Warner ET, Glasgow RE, Askew S, Goldman J, Ritzwoller DP, Emmons KM, Rosner BA, Colditz GA. Obesity treatment for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients in primary care practice. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:565–574. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinrich E, Candel MJJM, Schaper NC, de Vries NK. Effect evaluation of a Motivational Interviewing based counselling strategy in diabetes care. Diabetes Res Clin Practice. 2010;90:270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnes RD, White MA, Martino S, Grilo CM. A randomized controlled trial comparing scalable weight loss treatments in primary care. Obesity. 2014;22:2508–2516. doi: 10.1002/oby.20889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He XZ, Baker DW. Changes in weight among a nationally representative cohort of adults aged 51 to 61, 1992 to 2000. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodenlos JS, Brantley PJ, Jones G. Weight gain trajectory over 3-years among low-income predominantly African American medical patients. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35:S55–S55. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes RD, Ivezaj V, Grilo CM. An examination of weight bias among treatment-seeking obese patients with and without binge eating disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;77:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivezaj V, Kalebjian R, Grilo CM, Barnes RD. Comparing weight gain in the year prior to treatment for overweight and obese patients with and without binge eating disorder in primary care. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudson JI, Lalonde JK, Coit CE, Tsuang MT, McElroy SL, Crow SJ, et al. Longitudinal study of the diagnosis of components of the metabolic syndrome in individuals with binge-eating disorder. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1568–73. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grilo CM, White MA. Orlistat with behavioral weight loss for obesity with versus without binge eating disorder: randomized placebo-controlled trial at a community mental health center serving educationally and economically disadvantaged Latino/as. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnes RD, Ivezaj V, Martino S, Pittman BP, Grilo CM. Back to basics? No weight loss from motivational interviewing compared to nutrition psychoeducation at one-year follow-up. Obesity. doi: 10.1002/oby.21972. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shephard RJ. PAR-Q, Canadian Home Fitness Test and exercise screening alternatives. Sports Medi. 1988;5:185–195. doi: 10.2165/00007256-198805030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fairburn C, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorders Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge Eating: Nature, Assesment and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Lozano-Blanco C, Barry DT. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination in patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;35:80–85. doi: 10.1002/eat.10238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnes RD, Masheb RM, White MA, Grilo CM. Comparison of methods for identifying and assessing obese patients with binge eating disorder in primary care settings. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44:157–163. doi: 10.1002/eat.20802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck AT, Steer R. Manual for the revised Beck depression inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levesque CS, Williams GC, Elliot D, Pickering MA, Bodenhamer B, Finley PJ. Validating the theoretical structure of the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (TSRQ) across three different health behaviors. Health Educ Res. 2007;22:691–702. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moyers TB. The relationship in motivational interviewing. Psychotherapy. 2014;51:358–363. doi: 10.1037/a0036910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brownell KD. The LEARN program for weight management: lifestyle, exercise, attitudes, relationships, nutrition. American Health Publishing Company. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Carroll LM. Community program therapist adherence and competence in motivational enhancement therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martino S, Ball S, Gallon S, Hall D, Garcia M, Ceperich S, Farentinos C, Hamilton J, Hausotter W. Motivational Interviewing Assessment: Supervisory Tools for Enhancing Proficiency. Salem, OR: Northwest Frontier Addiction Technology Transfer Center, Oregon Health and Science University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brunner E, Domhof S, Langer F. Nonparametric analysis of longitudinal data in factorial experiments. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Webber KH, Tate DF, Ward DS, Bowling JM. Motivation and its relationship to adherence to self-monitoring and weight loss in a 16-week internet behavioral weight loss intervention. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Webber KH, Gabriele JM, Tate DF, Dignan MB. The effect of motivational intervnetion on weight loss is moderated by level of baseline controlled motivation. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;22:4–12. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blaine B, Rodman J. Responses to weight loss treatment among obese individuals with and without BED: a matched-study meta-analysis. Eat Weight Disord. 2007;12:54–60. doi: 10.1007/BF03327579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]