Abstract

Objective. To develop a measure of organizational culture in academic pharmacy and identify characteristics of an academic pharmacy program that would be impactful for internal (eg, students, employees) and external (eg, preceptors, practitioners) clients of the program.

Methods. A three-round Delphi procedure of 24 panelists from pharmacy schools in the U.S. and Canada generated items based on the Organizational Culture Profile (OCP), which were then evaluated and refined for inclusion in subsequent rounds. Items were assessed for appropriateness and impact.

Results. The panel produced 35 items across six domains that measured organizational culture in academic pharmacy: competitiveness, performance orientation, social responsibility, innovation, emphasis on collegial support, and stability.

Conclusion. The items generated require testing for validation and reliability in a large sample to finalize this measure of organizational culture.

Keywords: organizational culture, academic pharmacy, Delphi, strategic planning

INTRODUCTION

References to the concept of organizational culture have become increasingly commonplace in academic pharmacy. Yanchick challenged academic pharmacists to examine the current culture of their organization as they continue to integrate new opportunities into their organization’s strategic plans.1 This corroborates a strong body of research suggesting that strategic planning is almost doomed to fail without first taking an assessment of the organization’s culture.2 This assessment of culture goes beyond a SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats), and is a comprehensive, inclusive, and time-consuming process.

Academic pharmacy has described the need to promote a culture of scholarship,3 assessment,4 diversity and inclusion,5 and one that promotes interconnectedness, camaraderie, and consistency across multi-campus institutions.6 A Council of Deans-Council of Faculty (COD-COF) Task Force of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) identified organizational culture/climate as one of four critical and interrelated elements to promoting a healthy, vibrant, and stable workforce, along with role of the department chair, faculty recruitment/retention, and mentoring as the other three elements.7 Their findings cite evidence that poor relationships with administrators and colleagues are the primary drivers behind academic turnover. They suggest that while faculty value engagement in challenging work, they must feel valued by their employing organization. Additionally, academic organizations must build a sense of community, with effective ones being driven by outcomes, rendering decisions based upon fact, and employ creative and supportive leaders.8 Academia needs transformational leadership that is proactive to a quickly changing landscape while steering diverse organizations with myriad embedded rules, procedures, and ethos in working toward shared goals.9

Despite all this, organizations that have “healthy” cultures remain uncommon, and are often plagued with negative language used to describe organizational direction and quality improvement initiatives.10 Willson found that unresolved conflicts about organizational culture create breakdowns of rules and ensuing pessimistic outlooks among its constituent faculty members,11 while the climate of many academic organizations has been described as troublesome and pessimistic.12

The concept of organizational culture can be unwieldy to grasp and can mean different things to different stakeholders within and outside an organization. Schein defined organizational culture as “a set of basic tacit assumptions about how the world is, and ought to be, that a group of people share and that determines their perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and to some degree their overt behavior.”13 While more in-depth than some, this definition makes the concept of organizational culture more difficult to understand and to measure. Tierney has among the more oft-cited and frequently conceptualized rendering of organizational culture, stating that it simply reflects “how things are done around here” as manifested through language, symbols, rituals, values, beliefs, and behavior.14

The measure of organizational culture is controversial. Most measurement tools adopt either a typological (ie, what type of organization is it?) or a dimensional approach, which describes a culture by its position on several continuous variables.15 The instruments vary considerably in their having a theoretical underpinning. Many examine employee perceptions about their working environment, but only a few try to examine the values and beliefs that inform those views. Two of the latter are the Competing Values Framework and the Organizational Culture Inventory.16,17 A review of many of these measurement approaches suggest strengths and limitations of each.15

Sporn noted that universities are complex and contain multiple variations of organizational culture, such as individual, disciplinary, and institutional levels.18 Kuo argued that organizational cultures in institutions of higher learning are more complex, owing to intellectual purpose and department/discipline-centered structures and that academic organizations are rich in cultural meanings embedded in everyday communication.19 Clark outlined three levels of culture in higher education: the culture of the discipline, the culture of the enterprise, and the culture of the academic profession.20 Sporn argued further that the lack of understanding of organizational culture exhibited by leaders was inhibiting their ability to lead their institutions in effectively addressing the challenges facing higher education.18 Moreover, it is thought that by studying organizational culture, administrators could enhance their decision-making.21 The existence of subcultures in an organization, particularly in the academic setting, make it that much more important to use a comprehensive measure to evaluate organizational culture and make important decisions based upon that evaluation.

Measuring organizational culture in an academic setting is difficult, yet important. In addition to aforementioned reasons, prospective faculty and students are going to gauge the culture even if informally when selecting an institution to study or work.22 Academic pharmacy leaders like deans and chairs face increasingly difficult dilemmas, and in doing so must consider structural, human resource, political, and symbolic frames to guide these decisions.23

One of the more commonly used measures of organizational culture is the Organizational Culture Profile (OCP).24 The OCP uses a dimensional rather than typological approach for capturing nuance and measurement for internal and external outcomes of different facets of culture. Also inherent to its measure is the distinction between climate and culture, where the former is temporal and subject to manipulation by people with power and influence, while the latter can be affected, but involves a more holistic, comprehensive, and evolutionary approach.25 The OCP is also among the few instruments to have provided and demonstrated information on effective internal consistency reliability and construct validity.26 Additionally, it is designed to present an entire profile of an organization.

While employed in a variety of industries, the OCP is not widely used in measuring culture in academic organizations. In fact, perhaps due to the inherent difficulty in measurement, a typological approach has been used more often in academia. A typological approach can be especially useful for describing academic culture, as the different facets of culture can be situated, or placed within context of its three pillars: teaching, scholarship, and service. The OCP also has as its foundation, multidimensional aspects including supportiveness, innovation, stability, and social responsibility, which are all important in the higher education context.

Academic pharmacy has some unique properties within an academic organization, given the professional/post-doctoral nature of its primary product, and like medicine and nursing, its nearly inextricable link with practice. The OCP was able to effectively predict pharmacists’ MTM activities and their wherewithal to engage in prescribing.27,28 The OCP’s domains, including social responsibility, innovation, stability, performance orientation, and others, would appear to lend themselves well for use in measuring academic culture. Thus, the aim of this research was to develop a measure of organizational culture in academic pharmacy, by adapting the OCP, and thus identifying characteristics of an academic pharmacy program that would be impactful for internal (eg, students, employees) and external (eg, preceptors, practitioners) clients of the program.

METHODS

The two Institutional Review Boards of the study investigators reviewed and approved the study under exempt status from full review. A three-iteration (three round) Delphi procedure involving pharmacy faculty was conducted in the summer of 2016. A Delphi technique is a systematic procedure for arriving at a reasoned consensus.29,30 The Delphi has three primary features: anonymity, iteration and controlled feedback, and statistical group response.31 The Delphi was chosen over other face-to-face techniques (eg, a focus group) to minimize the bias of dominating individuals, groupthink, and irrelevant communications.30 A Delphi was particularly useful in this study for two reasons. First, the participants spanned a wide geographic distance. Second, use of a Delphi abated the likelihood that higher or more senior level participants will influence the junior members.32 Overall, Delphi procedures tend to yield more accurate group estimates because of the controlled anonymous feedback.30

The first-round questionnaire of a Delphi consists of open-ended and some close-ended questions to canvass opinions on a particular topic.31 Subsequent group responses are summarized and returned to panelists who may modify their contributions in light of new shared opinions.33 The success of any Delphi procedure hinges upon the characteristics of its composite panel members. Panel members should be willing and able to take part in an iterative process and have the potential to submit valuable contributions to the process.34 As such, the sampling used to gather potential participants is usually purposive. The impetus for selecting potential panelists as a whole should take into account their representativeness, ie, a range of relevant perspectives.35 A Delphi panel may consist of a range of members, with accuracy in group responses said to be maximized at approximately 20 members.30

The authors of the study created a list of possible faculty candidates as full-time academics from colleges/schools of pharmacy in the United States and Canada. Candidates were identified based on their knowledge of organizational culture from literature or actual experience. The potential panelists were selected among those who had published one or more papers in organizational behavior milieu, and/or having experience as an officer in AACP or another professional organization, and/or leadership in some other activity such as committee chair for a national professional organization. Additionally, potential candidates were selected to ensure representation of public and private as well as research versus teaching-intensive institutions. They also were selected to include representation from the biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences, clinical, and social/administrative sciences of pharmacy. The panelists also represented various ranks of academic appointment (assistant, associate, full professor), and with some having administrative responsibility (chair, vice-chair, assistant/associate dean, dean) and others without. A list of 38 candidates was generated, with a target of 20-25 initial participants, knowing that 100% participation even among those who agreed to participate beforehand was unlikely. After contacting 26 potential participants, 24 agreed to do so, signed, and returned the letter of informed consent, which included information that they would receive a $200 honorarium for their time and effort so long as they completed all rounds of the Delphi.

The survey instruments for each Delphi round was created and disseminated using online survey software. The purpose of the first round was to determine whether domains and specific items comprising the OCP were, or were not appropriate for inclusion in a measure of organizational culture in academic pharmacy and to determine additional items and other changes that the Delphi participants deemed appropriate. As such, the Round 1 Delphi instrument provided an operational definition of organizational culture36 that served as a foundation for creating the original OCP and many other adaptations or models of organizational culture. The participants were reminded that in this round like others to follow it, they were to render judgments based upon what they believe is an appropriate measure of organizational culture, and not necessarily what they have, or have not experienced at their institution.

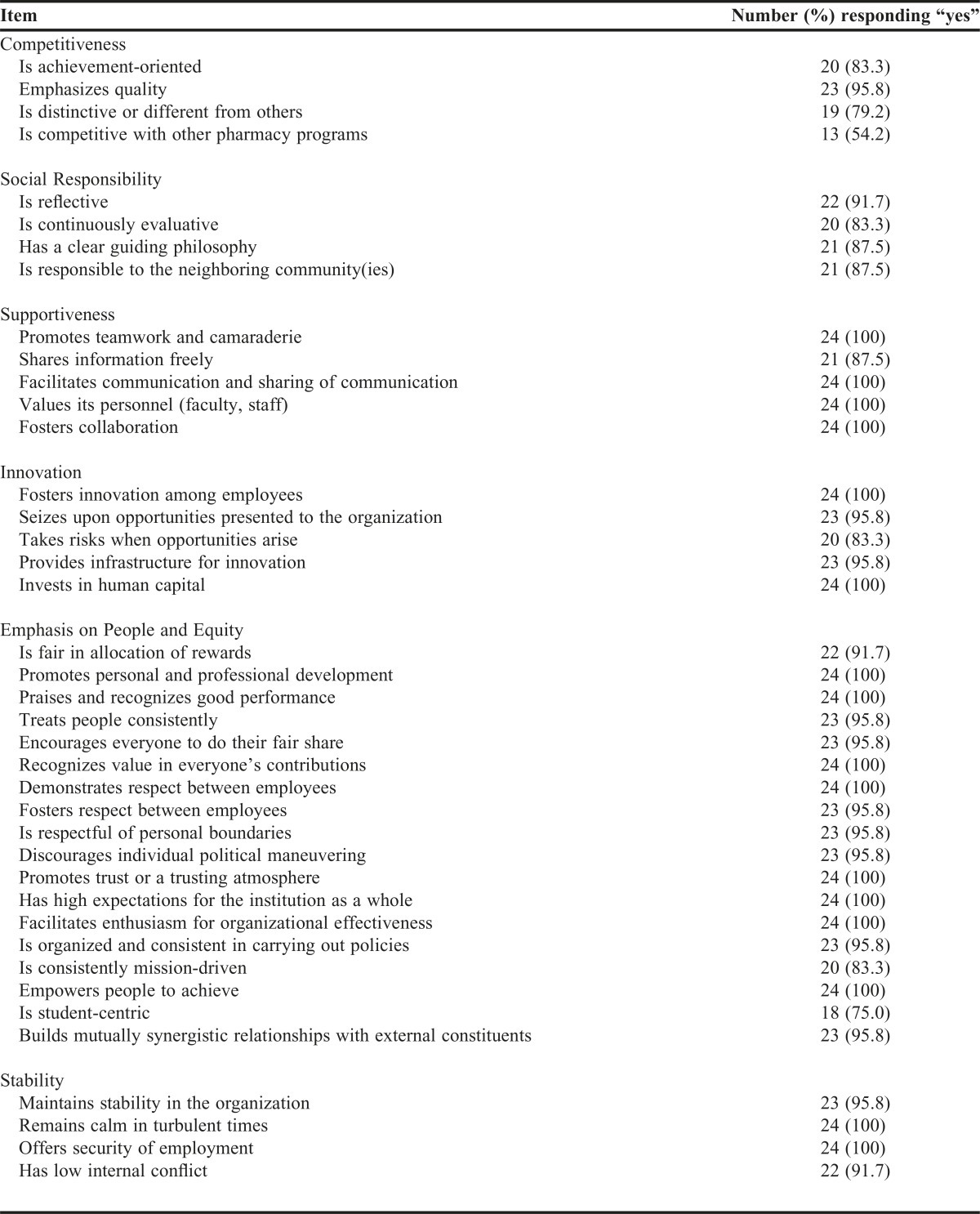

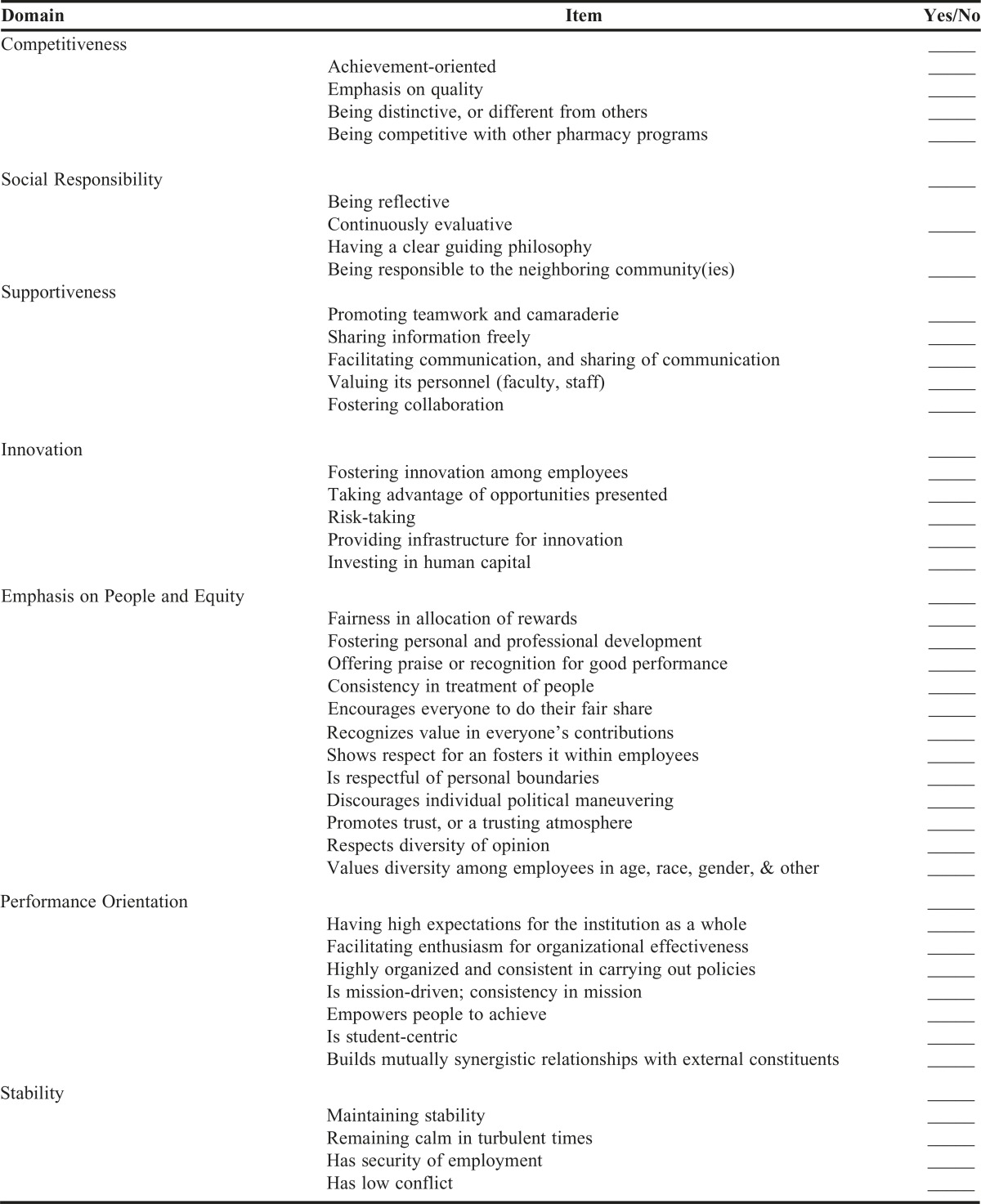

The panelists were asked to provide a yes/no answer as to whether each of the 41 items should remain in the measure for academic pharmacy (Appendix 1). The study investigators made some minimal changes from the OCP, such as making the verb tense of items consistent and the addition of two items on students and on diversity of opinion. These closed questions were accompanied by three open-ended questions asking participants whether any of the items should be considered but reworded or rephrased given the unique academic environment for which it was being created; whether any of the items might belong to another domain, and whether there should be consideration of additional items or domains for the measure of organizational culture in academic pharmacy.

The responses from Round 1 were reviewed for clarity and redundancy, reordered, and tabulated.33 Comments from the open-ended questions were evaluated. While knowledge and principles from the Delphi technique served as a guideline in doing so, there was no systematic attempt to evaluate the qualitative comments, per se, and this is in line with comment review.33 The investigators (all six) reviewed and agreed on evaluation of open-ended comments. These comments combined with the results from responses to the closed questions (Table 1) resulted in an amended set of items comprising the survey for Round 2. This survey proffered a new, putative domain of ‘emphasis on collegial support’ from the previous two “supportiveness” and “emphasis on people and equity” domains. It also included rewording of several items, elimination of two more, and the addition of two new items related to students and to camaraderie between colleagues. This list of items served as the basis for the second round questionnaire. In Round 2, participants were asked to rate the items on two, linear numeric scales of importance ranging from 1 to 4 (1=not important at all, 2=slightly important, 3=important, 4=extremely important) for potential contribution to the measure, and then on a second 4-point scale on potential impact.37 The means and interquartile ranges of responses to each item were calculated prior to initiation of Round 3.

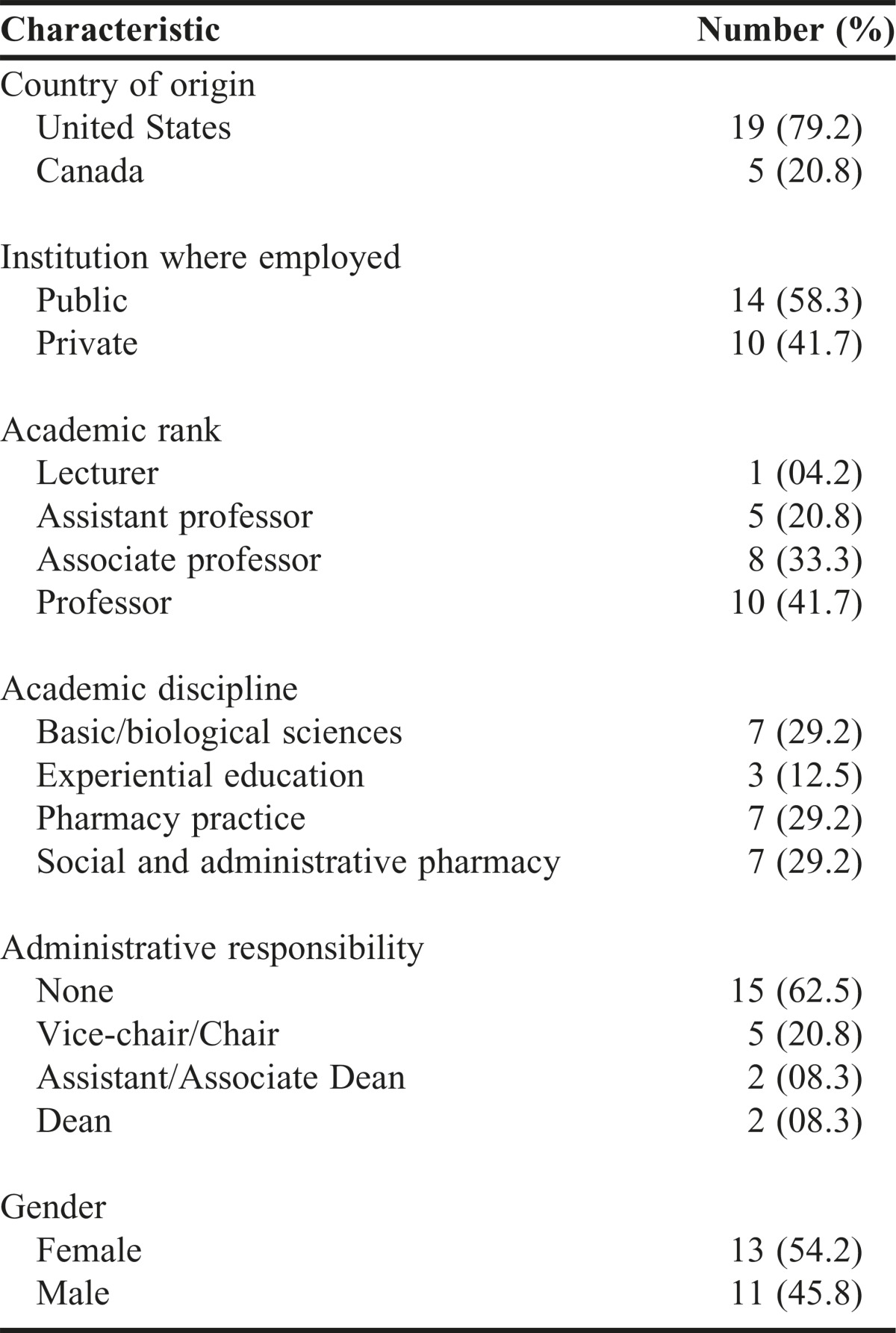

Table 1.

Characteristics of Delphi Panel Participants

Round 3 consisted of the same items in Round 2, with evaluations on the same scales. There were no comments from Round 2 that suggested changes in any of the items in forming the Round 3 survey. The survey for Round 3 was personalized for each participant. Respondents were provided their Round 2 responses, along with the items’ mean and interquartile ranges. Panelists may change their responses to the items on both scales after they have considered the grouped responses from their panelist colleagues. Panelists were asked to provide a qualitative response as to why they elected a response choice outside the interquartile range from their colleagues if they did so. This is to assist in the formation of a consensus and gather information as to why certain members could have differing opinions about the merits of a particular item.38 Additionally, Round 3 asked each participant to self-evaluate their own expertise in the general area of organizational culture, ie, their level of comfort and ease in completing the Delphi tasks, on a numeric scale from 1 to 4.29 There is no gold standard for achieving consensus; however, it is generally accepted that a tightening and overall narrow interquartile ranges are indicative of a consensus.30 The study investigators believed that the responses from Round 3 obviated the need for a fourth round. While subject to interpretation, the study investigators opted that the final instrument (final results) be the list of items whose mean score was at least 3.0 on both scales after Round 3.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the panel participants are provided in Table 1. There were six lecturers and assistant professors, eight associate professors, and 10 professors. Pharmacy sub-discipline was well represented, as were the gender of participants, and the type of institution (public versus private) to which they belonged. Nine of 24 participants had a designated administrative role, spread across vice chair, chair, assistant/associate dean, and dean appointments.

All 24 panelists responded to the Round 1 survey. The qualitative comments dealt with clarity of a few of the items, suggestions for consolidating factors, or domains of the items, concerns about the concept of competitiveness, and caution about use of certain words with potentially various meanings, such as the word “fair” and “distinctive,” along with the need for certain qualifiers such as “appropriate” risk-taking, as opposed to simply “risk-taking.” The quantitative responses to the dichotomous “yes/no” question as to whether the item belongs in the measure are found in Table 2. The majority of respondents supported the inclusion of each item proffered in the Round 1 survey. Specifically, there were a number of items with unanimous support and others with only two to three dissenters. Five of the items had four to six panelists express disapproval toward them. These were several items on competitiveness, and others on risk-taking, and being student-centric. While there is nothing definitive to suggest striking or amending an item based upon the proportion of Delphi panelists who deem it unworthy, the researchers reviewed those items that received the most number of dissenting votes. Moreover, many of the qualitative comments reinforced some of the more “suspect” items, offered advice to amend them. As such, this feedback from the panelists resulted in an amended set of items comprising the Round 2 survey.

Table 2.

Delphi Round 1 Responses to Appropriateness of Item to Measure Organizational Culture

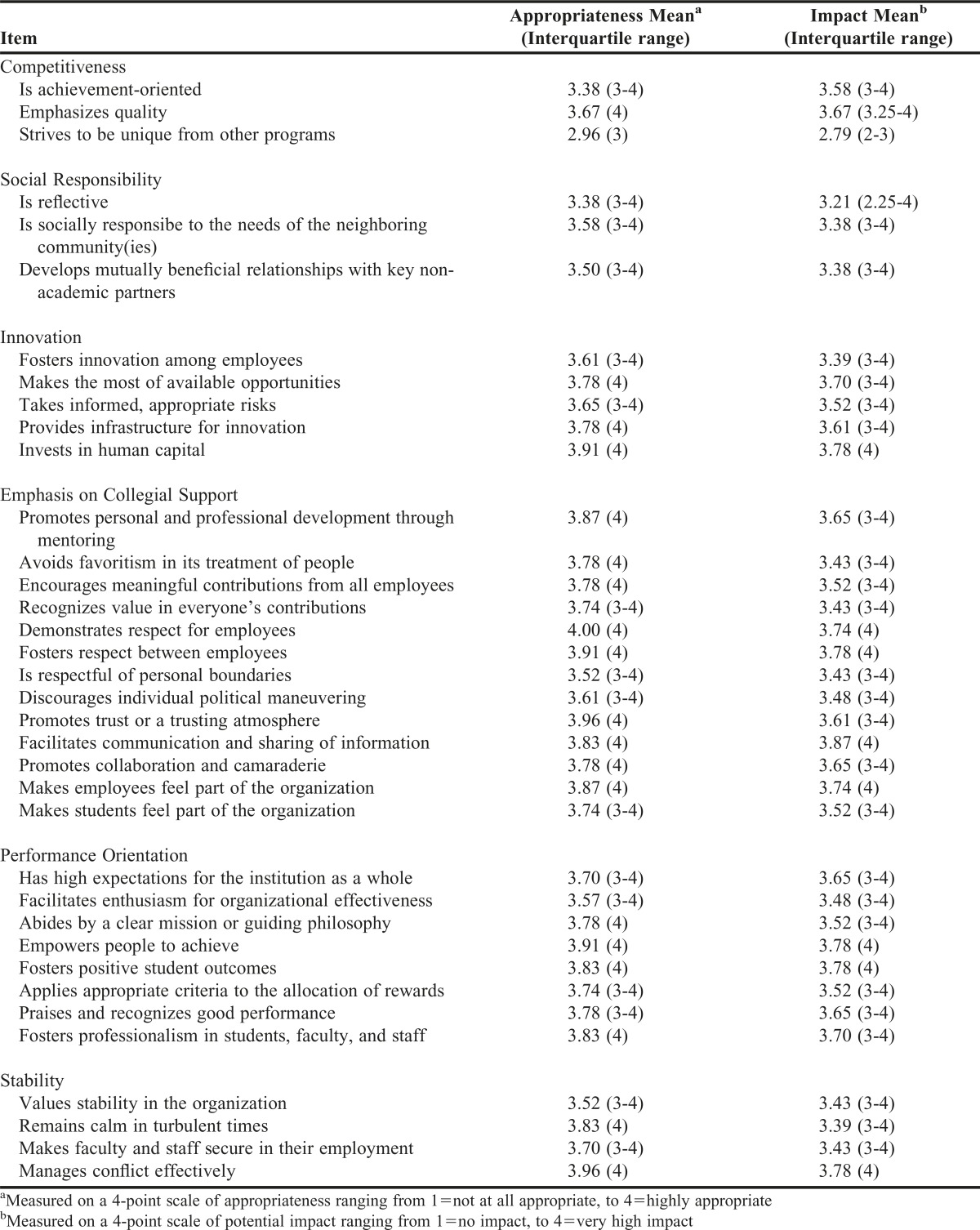

The Round 2 survey scaled participants’ responses to 37 items. All 24 panelists responded to the survey. The items were scaled on appropriateness and impact. The results of these evaluations are provided in Table 3. The mode for each of the items on the appropriateness scale was 4 (very much appropriate) or 3 (moderately appropriate). Items with still favorable yet lower ratings than most other items concerned the organization striving to be unique (changed from previous “competitive” in Round 1), being achievement-oriented, developing relationships with key non-academic partners, fostering innovation among its employees, discouraging political maneuvering, encouraging meaningful contributions from all employees, recognizing value in everyone’s contributions, being respectful of personal boundaries, facilitating enthusiasm for organizational effectiveness, and valuing stability within the organization. Since the responses were favorable overall, the interquartile range of responses (25th to 75th percentile) was already tight for most of the items even in Round 2, with the range for most being 3 to 4 on the 4-point scale. Similar results were observed for evaluation of items on the impact scale. Responses to items on the impact scale were rather similar, generally with slightly lower response means. Some items, though, were viewed more favorably for impact than appropriateness, such as being achievement-oriented and facilitating communication. Lower ratings were accorded to items pertaining to uniqueness, development of external partnerships, taking informed appropriate risks, recognition of everyone’s contributions, respect for personal boundaries, and facilitating enthusiasm for organizational effectiveness. There were few qualitative comments acquired from Round 2. Several panelists said that they had no concerns, were very interested in the project, thought the measure to be extremely effective, although two noted the importance that administrators maintain transparency in dealing with internal clients of the organization. Two panelists commented with their struggle to embrace the concept of measuring competitiveness, or even distinctiveness.

Table 3.

Quantitative Responses from the Delphi Round 2 Survey

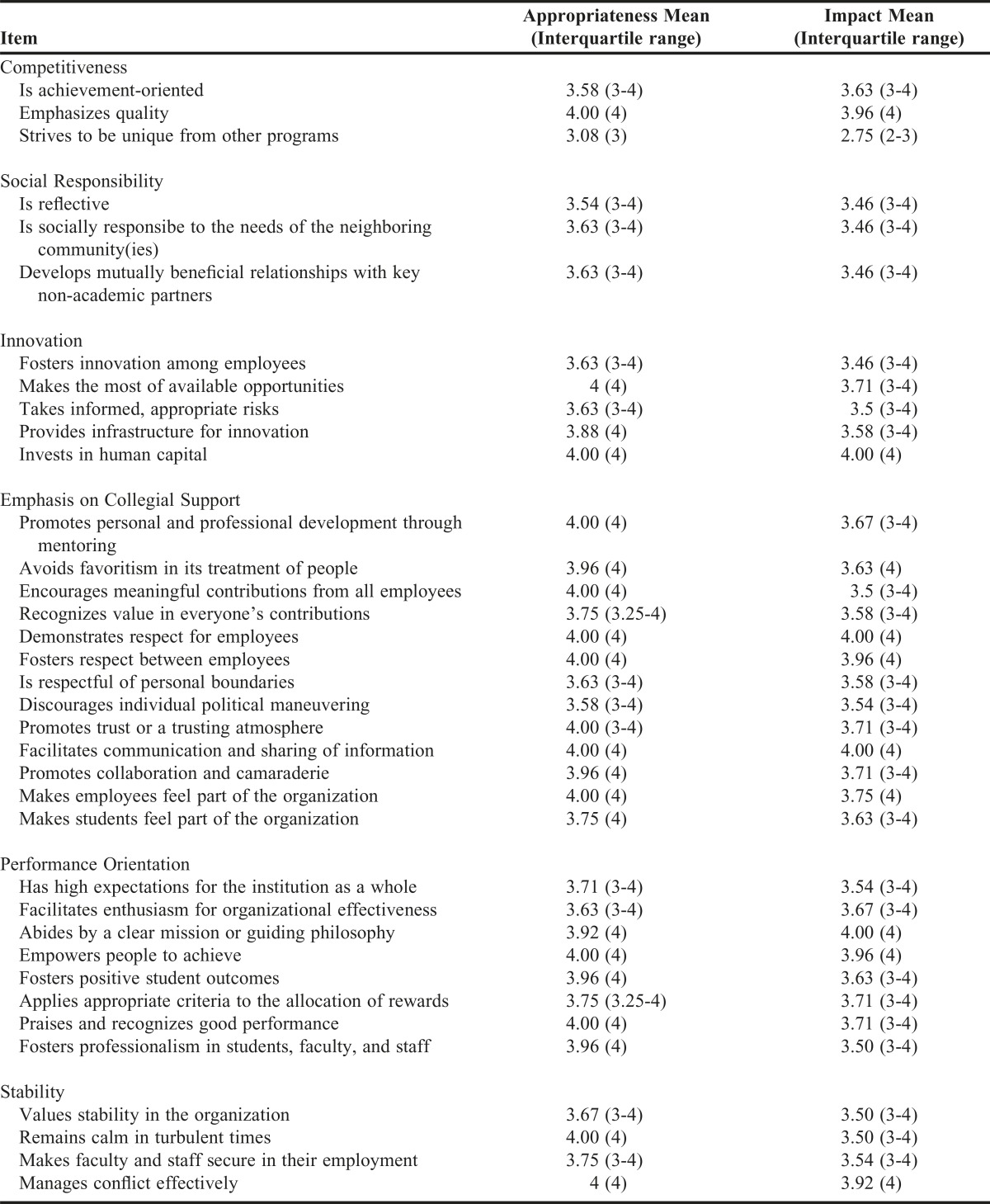

The Round 3 survey quantitative responses are provided in Table 4. All 24 panelists responded to the Round 3 survey. The dispersion of responses to most of the items on both scales was already tight after Round 2. The Round 3 responses indicate even tighter, or smaller dispersion of responses for many of the items on both scales. While often not used in Delphi research, it can be noted that the standard deviation of responses to these items grew smaller as well.

Table 4.

Quantitative Responses from the Delphi Round 3 Survey

Overall, 35 items had a mean of 3.0 or above on both scales. Additionally, the small dispersion of responses was indicative of a consensus having formed around these items. As such, these items across six domains can be said to be aspects of an academic pharmacy organization’s culture and used in a measure of such. The item not rated with a 3.0 dealt with the concept of competiveness, even while the two remaining items in this domain were rated highly. The panelists rated themselves with an overall level of expertise of 2.66 on the 4-point scale, with responses ranging from 1 to 4. Two panelists rated themselves with a 1, while the mode response on the expertise scale was 3. The panelists who deemed their expertise with a value of 1 provided similar input as did others, even while these individuals and the majority of those responding with a 2 were at more junior levels of experience. In total, this process and the self-ratings of expertise observed here have been shown to be a good indication of the appropriateness of the panel’s composition.30

DISCUSSION

A Delphi panel was largely in agreement with the domains and items proffered by Sarros and colleagues24 to measure organizational culture but provided some adjustments and additions to that instrument specific for the academic pharmacy context. The social responsibility, innovation, performance orientation, and stability domains remained similar to the domains proffered in the OCP, albeit with changes in wording in several of the items and the addition of new items/concepts such as empowerment of people, fostering enthusiasm, and several items related to students. Many of the new items dealt more specifically with internal clients, except for one on establishment of relationships with external organizations, presumably for the benefit of student learning in pharmacy practice experiences, for faculty practice sites, and for research collaboration. This corroborates work by Foreman-Kready, which emphasized the willingness and ability of academic entities to form mutually beneficial partnerships and their preference to engage the community as critical components of that institution’s culture.39 Additionally, inclusion of a new item on professionalism is noteworthy and underscores the emphasis placed on this concept by academic pharmacy.40

More dramatic differences were observed with remaining OCP constructs. The panel did not favor the concept of competitiveness, but supported similar items related to those in the OCP domain such as being achievement–oriented. Still, some panelists were hesitant to endorse even the concept of distinctiveness of a program. Inferences can be made from a few qualitative comments, but the reason for such hesitancy as a whole is not known. Comments suggested that pharmacy programs operated under the auspices of accreditation standards and might try to distinguish themselves to be attractive for prospective students but insisted that in essence, all of the schools “worked together” and “all facing the same opportunities and challenges.” Still, the lower ratings for the competitiveness concept was surprising, particularly as prospective student applications are down and as extramural support opportunities are scarce. The lower ratings for competitiveness and/or distinctiveness were spread equally across panelists of different rank and type of institution. Perhaps these results are reflective of a spirit that pharmacy programs do not, or should not strive to be so unique in executing the tripartite mission of teaching, scholarship, and service. This despite evidence suggesting attempts to manage the “symbolic” side of universities and constituent programs given the emergence of a global rivalry among academic institutions and of a related market competition among universities for outstanding researchers, able students, and funds from various sources.41 Still, when applying these items for further use and psychometric testing, it is possible, among many other variations, that the two items remaining in the proposed “competitiveness” domain load into a different factor/domain, such as performance orientation, thus resulting in five domains. Also, rather than separate constructs for supportiveness and emphasis on rewards, the panelists chose to combine many items on those OCP domains into one as “emphasis on collegial support,” thus also stressing the nature of academic organizations’ members sharing responsibility for culture, governance, decision-making, and outcomes.42,43

Organizational culture has been critically examined in the context of academic institutions. The importance of organizational culture on the performance of entire institutions and on outcomes related to faculty (eg, turnover, scholarly productivity) has been inferred frequently.44,45 It has been suggested that both the actual culture and the perceived culture by different entities within the academic organization have an impact on the level of camaraderie and degree of optimism about that institution moving forward, and that perceptions of the culture often vary between people in different positions or rank within the program.36 Additionally, through the process of “teaching” and “learning,” an academic organization’s culture in itself is salient for scholarly productivity and internal client relationships.46 Organizational culture may impact faculty morale, their career aspirations and commitment to their discipline outside more immediate institutional service responsibilities.47 A limitation in these stated implications is that culture is often implied, or sometimes measured crudely, but infrequently inventoried in a valid and reliable fashion to make these assumptions. Additionally, organizational culture in academic institutions rarely takes into account the contribution, or manifestation of such a culture from students attending the institution, even while arguments are made for instilling a culture of interprofessional education.48

It has been argued that a lack of understanding about the role of organizational culture in improving institutional performance inhibits the ability to address the challenges facing higher education; and that because an institution’s culture is a reflection on what and how things are done, and who is involved, it plays a central role in quality improvement.49 Higher education, in general, and specifically academic pharmacy, has called attention to the importance of leadership in shaping culture and organizational success. Two decades ago, Hull pointed out that the highest task of leadership development is to shape a robust culture congruent with the mission of the institution.50 Academic pharmacy programs through self-study are engaged in continuous quality improvement; and striving for excellence and preparation for change management requires that significant attention be accorded to organizational culture paradigms.51 The salience of organizational culture is interwoven throughout an entire academic institution’s makeup, and impacts the larger academy in areas of professionalism, resource allocation, planning for scholarship, and educational programming.52 Maintaining a handle on organizational culture is critical for succession planning and attunes current and future leaders to necessary elements in striving for excellence.53

Sequencing of organizational culture change and leadership development is not linear; they are both concurrent processes requiring concomitant attention.54 It can be said that recruitment for any and all faculty positions demands cognizance of organizational culture, which will be examined by prospective faculty candidates when they are evaluating positions and a fit to match their values with those of an academic institution.55 Even while lacking complete consensus, the majority of findings and expert opinion suggest culture to be malleable, but through an evolutionary and iterative process that requires not only transformative leadership behaviors, but patience and understanding of larger systems.56 Thus, while changes can and should be made to address particular areas of the program (eg, assessment, hiring, facilitating scholarship, increasing the student applicant pool, etc.), these changes should be constructed and implemented in a manner that considers culture, subcultures, resistance to change, and the effects that the changes might have on other working components of the organization.57

When examining organizational culture, one quandary is whether there is only one, or whether there are subcultures throughout the institution. It has been argued that in academic institutions, there are not only subcultures, but even microcultures punctuated by schools/colleges, programs, departments, and even other units.58 As such, the consideration of culture in a particular program, such as pharmacy, is quite appropriate. The considerations and measure of culture offered by this research and resultant instrument can be useful in measuring culture in academic pharmacy, benchmarking changes as a result of intervention and/or leadership initiatives, and even measuring departments or other subcultures within the organization. It allows an academic pharmacy program to move beyond conjecture and assumptions about organizational culture and to codify or track it more empirically.

The results of any Delphi procedure are limited by the expertise of the panel participants and the level of diligence with which they carried out the process. All 24 panelists participated in all three rounds, which is indicative of their investment in the study; however, given their quick convergence on consensus, it cannot be ruled out that at least some participants took a more expeditious approach to their tasks. Panelists were provided a $200 honorarium for participation, more so to recognize the time involved for participating in multiple rounds of a project than to induce response, per se. Given the quality of their contributions, it is unlikely that panelists completed all rounds of the Delphi, but that prospect cannot be entirely ruled out. Several panelists rated themselves as having low expertise in the area of organizational culture, and this could have helped to create such positive reactions toward many of the items. However, it should be noted that many of these items were a part of a widely known organizational culture inventory (OCP), so it might not be surprising that they were viewed with such favor here, particularly after adaption for the academic pharmacy context. No matter how knowledgeable participants are, a different set of participants may have generated a slightly different set of items. A purposive sampling strategy was used to gain representation from the basic, clinical, and social/administrative pharmaceutical sciences, in addition to representation by type of institution, faculty rank, and participation in administrative activities. The fact that consensus was achieved easily by a panel diverse in experience and type of institution underscores a strength of the study design and of the Delphi process in that they all recognized similar phenomena contributing to organizational culture. Despite these limitations, the Delphi procedure incorporates inherent strengths in its design, including mitigation of groupthink. The investigators utilized the operational definitions and initial set of items based upon the OCP.24 Utilizing a more open-ended procedure or an entirely different foundation for Round 1 of the Delphi could have yielded alternative results.

The proposed list of items requires validation and reliability testing for use in a measure of organizational culture. The items generated from this process should be employed in studies with larger sample sizes and validated using quantitative designs. Further refinement of the measure would include factor analysis to evidence construct validity. The use of this study’s procedures to inform item generation followed by the aforementioned quantitative approaches is commensurate with recommendations for the development of measures used in survey research.59 Once completed, this measure should be useful as is or adapted for any of a number of post-secondary professional programs in describing culture.

The panel participants in this process consisted only of pharmacy faculty. As such, it might be said to have some unique properties related to pharmacy; however, given that the participants were not provided instruction nor did they comment overtly on items particular to pharmacy made the items generated here more useful, or at least readily adaptable to faculty in other areas, which lends further strength to this study’s design.

CONCLUSION

A Delphi procedure was used to develop a list of 35 items across six domains to measure organizational culture in academic pharmacy. The generated list contains items that are reflective of previously validated measures but which reflect unique properties of academia and professional programs of learning, specifically, with consideration of the autonomous and collegial environment inherent to higher learning institutions, inclusion of student considerations, and mindfulness of some standardization under the auspices of accreditation. The items generated by the procedure provide not only a mechanism for measuring, but also suggest the properties inherent to a strong culture that serves administrators, faculty, staff, students, and external clients alike.

Appendix 1. Round 1 and Round 2 Delphi Survey Questionnaires

Identifying a Measure of Organizational Culture in Academic Pharmacy: A Delphi Study

Round 1 Survey

Thank you for agreeing to participate in our Delphi process. Your contributions will be invaluable toward describing various facets of organizational culture in academic pharmacy. Once created, we will be able to examine the relationships between a program’s culture with certain aspects of the organization’s success, and various aspects of faculty vitality, productivity, work satisfaction, commitment, and citizenship behaviors. The purpose of Round 1 in the Delphi process is to determine the relevance of previously identified constructs in defining organizational culture in academic pharmacy and to solicit your ideas for additional constructs and particular items that might define it. Again, organizational culture has many definitions, but for our purposes, we will simply refer to it as the values and behaviors that contribute to the unique social and psychological environment of an organization. It includes an organization’s expectations, experiences, philosophy, and values that hold it together, and is expressed in its self-image, inner workings, interactions with the outside world, and future expectations. It is based on shared attitudes, beliefs, customs, and written and unwritten rules that have developed over time. With this background we are asking you to answer the following questions:

1. Please answer “yes” or “no” as to whether you believe the following domains and items are appropriate in describing organizational culture. Remember, this is not a question of whether or not this potential aspect of culture is present in your organization. Rather, it is the extent to which YOU BELIEVE this is an issue that should comprise, or helps us to describe academic culture, in general, given the definition above.

2. Please let us know of any of the above that you think might belong in a measure of organizational culture in academic pharmacy, but believe that it should be reworded, or amended somehow?

3. Please let us know if there are items above that you feel important but perhaps belong in another domain, particularly if reworded a bit.

4. Please tell us of any other domains and/or items you might feel important, or appropriate for inclusion in a measure of organizational culture in academic pharmacy, again, considering the definition given, and not necessarily something you want to point out that is occurring, or not occurring at your current institution.

Identifying a Measure of Organizational Culture in Academic Pharmacy: A Delphi Study

Round 2 Survey*

Part 1.

From your Round 1 responses and a careful review of the literature, we have proposed an initial set of items listed below that are potential items representative of organizational culture in academic pharmacy. The purpose of Round 2 is to determine the appropriateness of these items to compose this measure, and again, NOT to report which of these you have experienced or engaged.

We are asking you to rate each of these items for APPROPRIATENESS and IMPACT to compose the organizational culture measure. In other words, does this characteristic, good or bad, help to describe how the values and behaviors that contribute to the unique social and psychological environment of an academic pharmacy organization? We are also concerned with impact, as there are many possible values and behaviors assumed by an organization, but to measure culture, we are concerned with those that have an actual effect on the organization, and with a broad view of the organization to include both internal and external clients.

Part 2.

Please provide any additional comments regarding the domains, items, their placement, their wording, or other input about the proposed measure or the Delphi process in itself in which you are taking part.

*Not the complete survey. Actual survey listed all items and domains with their respective accompanying scales.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yanchick VA. Thinking off the map. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;72(6):Article 141. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kezar A, Eckek PD. The effect of institutional culture on change strategies in higher education: universal principles or culturally responsible concepts? J High Edu. 2002;73(4):435–460. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy RH, Gubbins PO, Luer M, Reddy IK, Light KE. Developing and sustaining a culture of scholarship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article 92. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piascik P, Bird E. Creating and sustaining a culture of assessment. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5):Article 97. doi: 10.5688/aj720597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yanchick VA, Baldwin JN, Bootman JL, Carter RA, Crabtree BL, Maine LL. Report of the 2013-2014 Argus Commission: Diversity and inclusion in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(10):Article S21. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7810S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison LC, Congdon HB, DiPiro JT. The status of US multi-campus colleges and schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(7):Article 124. doi: 10.5688/aj7407124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desselle SP, Peirce GL, Crabtree BL, Acosta D, et al. Pharmacy faculty workplace issues: findings from the 2009-2010 COD-COF Joint Task Force on Faculty Workforce. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(4):Article 63. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Freed JE, Klugman MR, Fife JD. A Culture for Academic Excellence: Implementing the Quality Principle in Higher Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1997.

- 9.Belias D, Koustelios A. The impact of leadership and change management strategy on organizational culture. Eur Sci J. 2014;10(7):451–470. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meskill VP, McTague MJ. Nurturing new ideas: inhibitors and enhancers in the search for new ideas. Bus Off. 1995;29(5):46–48. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Willson R. The dynamics of organizational culture and academic planning. Plan High Educ. 2006;34(3):5–17. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson MS, Louis KS, Earle J. Disciplinary and departmental effects on observations of faculty and graduate student misconduct. J High Educ. 1994;65(3):331–350. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schein EH. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

- 14.Tierney WG. Organizational culture in higher education: defining the essentials. J High Educ. 1988;59(1):2–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott T, Mannion R, Davies H, Marshall M. The quantitative measurement of organizational culture in health care: a review of the available instruments. HSR: Health Services Research. 2003;38(3):923–945. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameron K, Freeman S. Culture, congruence, strength, and type: relationship to effectiveness. Res Org Change Dev. 1991;5(1):23–58. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cooke R, Lafferty J. Organizational Culture Inventory (OCI). Plymouth, MI: Human Synergistics; 1987.

- 18.Sporn B. Does a university have a culture? Stud High Educ. 2003;32(1):41–61. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuo HM. Understanding relationships between academic staff and administrators: an organizational culture perspective. J High Educ Policy Manage. 2009;31(1):43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark BR. Listening to the professoriate. Change. 1985;17(5):36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 21.St. Onge EL, Suda K, Devaud L, Wilson AF, et al. Approaches to management of dilemmas by leaders in academic pharmacy. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2012;4(2):78–83. [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacLaughlin EJ, Haase MR, Iron BK, McCall KL, et al. Assessing an academic pharmacy position: Guidelines for evaluating an institution and roles for new faculty. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2009;1(1):17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Reilly CA, Chatman J, Caldwell DF. People and organizational culture: a paired comparisons approach to assessing person-organization fit. Acad Manage J. 1991;34(3):487–516. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarros JC, Gray J, Densten IL, Cooper B. The Organizational Culture Profile revisited and revised: An Australian perspective. Aust J Manage. 2005;30(1):159–182. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ashansky NM, Broadfoot LE, Falkus S. Questionnaire measures of organizational culture. In: Handbook of Organizational Culture and Climate. Ashkanasy NM, Wilderom CP, Peterson MF (eds.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000.

- 26.Denison DR. What is the difference between organizational culture and organizational climate? Acad Manage Rev. 1996;21(3):619–654. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenthal M, Holmes E, Banahan B. Making MTM implementable and sustainable in community. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016;12(3):523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenthal MM, Houle SKD, Eberhart G, Tsuyuki RT. Prescribing by pharmacists in Alberta and its relation to culture and personality traits. Res Social Adm. 2015;11(3):401–411. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Helmer O, Brown B, Gordon T. Social Technology. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1966.

- 30. Dalkey NC. The Delphi Method: An Experimental Study of Group Opinion. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp. (RM-5888-PR); 1969 (June).

- 31.McKenna HP. The Delphi technique: a worthwhile research approach for nursing? J Adv Nurs. 1994;19(6):1221–1225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMurray AR. Three decision-making aids: braininstorming, nominal group, and Delphi technique. J Nurses Staff Dev. 1994;10:62–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna HP. A critical review of the Delphi technique as a research methodology for nursing. Int J Nurs Stud. 2001;38:195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(00)00044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Donabedian A. The Criteria and Standards of Quality. Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring. Vol II. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Admin. Press; 1982.

- 35.Mullen PM. Delphi: myths and reality. J Health Organ Manag. 2003;17(1):37–52. doi: 10.1108/14777260310469319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Deal TE, Kennedy A A. Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life. New York: Penguin Books; 1982.

- 37.Desselle SP. Pharmacists’ perceptions of pharmaceutical care practice standards. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1997;NS37(5):529–534. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hassell K, Hibbert D. The use of focus groups in pharmacy research: processes and practicalities. J Soc Adm Pharm. 1996;13(4):169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Foremean Kready S. Organizational Culture and Partnership Process: A Ground Theory Study of Community-Campus Partnerships. Doctoral Dissertation. Virginia Commonwealth University; 2011.

- 40.Berger BA, Butler SL, Duncan-Hewitt W, Felkey BG, et al. Changing the culture: an institution-wide approach to instilling professional values. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1):Article 22. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dill DD. The degredation of the academic ethic: Teaching, research, and the renewal of professional self-regulation. In: Barnett R (ed.), Reshaping the University: New Relationships Between Research, Scholarship, and Teaching. Buckingham, UK: McGraw-Hill/Open University Press; 2005.

- 42.Desselle SP, Semsick GL.Organizational citizenship behaviors in academic pharmacy Am J Pharm Educ 2016In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Folch MT, Jon G. Analyzing the culture of university: two models. High Educ Eur. 2009;34(1):143–154. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Souba WW, Mauger D, Day DV. Does agreement on institutional values and leadership issues between deans and surgery chairs predict their institutions’ performance? Acad Med. 2007;82(3):272–280. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180307e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ponnuswamy I, Manohar HL. Impact of learning organization culture on performance in higher education institutions. Stud High Educ. 2016;41(1):21–36. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Thakur GR. A Study of Organizational Behavior of Colleges of Education of Maharashtra State. Doctoral Dissertation. North Maharashtra University; 2014.

- 47.Lumpkin A. The role of organizational culture on and career stages of faculty. Educ Forum. 2014;78(2):196–205. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lavender C, Miller S, Church J, Chen RC, et al. Fostering a culture of interprofessional education for radiation therapy and medical dosimetry students. Med Dosi. 2014;39(1):50–53. doi: 10.1016/j.meddos.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Crouch JM. An Ounce of Application is Worth a Ton of Abstractions: A Practice Guide to Implementing Total Quality Management. Greensboro, NC: Leads Corp.; 1992.

- 50. Hull WE. The quality culture in academia and its implementation at Samford University. Paper presented at the AAHE Annual Conference on Assessment and Quality. June 12, 1996. Boston, MA.

- 51.Hall PD, DiPiro JT, Rowen RC, McNair D. A continuous quality improvement program to focus a college of pharmacy on programmatic advancement. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(6):Article 117. doi: 10.5688/ajpe776117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Linn AY, Altiere RJ, Harris WT, Sims PJ, et al. Leadership: The nexus between challenge and opportunity: Reports of the 2002-03 Academic Affairs, Professional Affairs, and Research and Graduate Affairs Committees. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3):Article S05. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Amburgh J, Surratt CK, Green JS, Galluci JM, et al. Succession planning in U.S. pharmacy schools. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(5):Article 86. doi: 10.5688/aj740586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ray KW, Goppelt J. Understanding the effects of leadership development on the creation of organizational culture change: A research approach. Intl J Train Develop. 2011;15(1):58–73. [Google Scholar]

- 55.DiPiro JT. A culture of hiring for excellence. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(5):Article 97. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bellot J. Defining and Assessing Organizational Culture. Doctoral Dissertation. Philadelphia, PA: Thomas Jefferson University; 2011.

- 57. Smerek RE. Cultural perspectives of academia: Toward a model of cultural complexity. In J.C. Smart (Ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research. New York: Springer Science+Business; 2010:381–405.

- 58.Martensson K, Roxa Stensaker B. From quality assurance to quality practices: An investigation of strong microcultures in teaching and learning. Stud High Educ. 2014;39(4):534–559. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hinkin TR. A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Org Res Methods. 1998;1(1):104–121. [Google Scholar]