Abstract

Objective. The Hiring Intent Reasoning Examination (HIRE) was designed to explore the utility of the CAPE 2013 outcomes attributes from the perspective of practicing pharmacists, examine how each attribute influences hiring decisions, and identify which of the attributes are perceived as most and least valuable by practicing pharmacists.

Methods. An electronic questionnaire was developed and distributed to licensed pharmacists in four states to collect their opinions about 15 CAPE subdomains plus five additional business related attributes. The attributes that respondents identified were: necessary to be a good pharmacist, would impact hiring decisions, most important to them, and in short supply in the applicant pool. Data were analyzed using statistical analysis software to determine the relative importance of each to practicing pharmacists and various subsets of pharmacists.

Results. The CAPE subdomains were considered necessary for most jobs by 51% or more of the 3723 respondents (range, 51% to 99%). The necessity for business-related attributes ranged from 21% to 92%. The percentage who would not hire an applicant who did not possess the attribute ranged from 2% to 71.5%; the percentage who considered the attribute most valuable ranged from 0.3% to 35%; and the percentage who felt the attribute was in short supply ranged from 5% to 36%. Opinions varied depending upon gender, practice setting and whether the pharmacist was an employee or employer.

Conclusion. The results of this study can be used by faculty and administrators to inform curricular design and emphasis on CAPE domains and business-related education in pharmacy programs.

Keywords: CAPE 2013, gainful employment, social and administrative science, business management

INTRODUCTION

The Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) designed the 2013 Educational Outcomes to guide pharmacy programs to produce graduates who are practice-ready. Released at the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Annual Meeting in July 2013, these outcomes were updated from previous versions in 2004, 1998, and 1992.1 The major difference between CAPE 2013 and previous versions was the addition of educational outcome goals outside the traditional boundaries of foundational, pharmaceutical, and clinical sciences. The outcomes were “…intentionally expanded beyond knowledge and skills to include the affective domain, in recognition of the importance of professional skills and personal attributes to the practice of pharmacy.”1

The new CAPE outcomes were constructed around four domains to guide the academy in educating pharmacists who possess: foundational knowledge that is integrated throughout pharmacy curricula, essentials for practicing pharmacy and delivering patient-centered care, effective approaches to practice and care, and the ability to develop personally and professionally. These domains are further divided into 15 specific subdomains, which are identified by one-word descriptors: learner, caregiver, manager, promoter, provider, problem solver, educator, advocate, collaborator, includer, communicator, self-aware, leader, innovator, and professional.1

Developed by a panel appointed by AACP and the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners, the CAPE outcomes have been formally incorporated into the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Standards 2016 (Section I, Standards 1-4).2 Together these set a new expectation for doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) programs to develop skills and abilities outside of foundational knowledge and clinical skills to develop practice-ready pharmacists who are employable and add value to the health care system.

The purpose of this project was to survey a broad sample of practicing pharmacists to determine their opinions and perceived value of the CAPE 2013 subdomains in determining the employability of a pharmacist candidate. Since the CAPE outcomes were created to focus PharmD programs on the knowledge, skills, abilities, and attitudes necessary to become competent, practicing pharmacists, it is important to gather evidence about the value and utility of these measures from practicing pharmacists. In recent years, pharmacy education has undergone significant transformation. The scope and level of education required to practice pharmacy in the US has increased as has the training provided to prepare pharmacists to better serve the increasingly complex therapeutic needs of patients. These changes along with significant economic shifts brought forth by a recession and an increase in the number of pharmacy graduates have combined to dramatically change the nature of the job market for entry-level practitioners. Large sign-on bonuses and generous tuition reimbursement programs have all but disappeared, and the pharmacy job market has shifted from a shortage situation to one where supply and demand are more equal.3 These educational and economic changes provide stimuli for pharmacy educators to take a step back and investigate how educational changes are or are not providing the training necessary to assure that pharmacy school graduates can be gainfully employed.

The Hiring Intent Reasoning Examination (HIRE) survey was designed to explore the utility of the CAPE 2013 outcomes by practicing pharmacists and employers, examine how each measure influences hiring decisions, and identify which of the CAPE subdomains are perceived as most and least valuable by practicing pharmacists. These data will provide valuable information to help guide the academy in developing better curricula to advance the quality of pharmacy graduates who are ready to practice when entering the profession.

METHODS

The research study was submitted and approved at the respective IRBs at four universities. Email lists of licensed pharmacists in four states (Arkansas, California, Ohio and North Carolina), were obtained from either a state board of pharmacy or from a list of alumni kept from a pharmacy program within a state. No attempt was made to check the lists for duplications if a pharmacist was licensed in more than one of the four states. The survey was administered from September 2014 to early December 2014. Each of the four schools separately administered the questionnaire to the pharmacists on their list through an electronic survey tool. Three schools used SurveyMonkey (Palo Alto, CA) and one used Qualtrics (Provo, UT). No incentives were provided to respondents. Follow-up emails were made after 30 days to non-responders to increase the response rate. Upon closure of individual surveys, results were compiled into one spreadsheet.

The questionnaire was divided into three sections: demographics, hiring characteristics, and CAPE outcomes. There were 15 demographic questions, five hiring characteristics questions, and six questions related to the CAPE outcomes. In addition to the 26 questions, the questionnaire began with an additional qualifying question to ensure that no one responded to the questionnaire multiple times. This helped to account for any situation in which a pharmacist was simultaneously licensed in more than one of the four states. The draft questionnaire was pilot tested by faculty and alumni from one of the schools participating in this project, after which minor adjustments were made.

The five hiring characteristic questions focused on 48 traits that pharmacy candidates might possess. Twenty-four of the characteristics were character strengths as defined by Martin Seligman.4 Examples of these character strengths included “demonstrates respect for feelings of others,” “actively listens to others,” and “is eager to explore new things.” The remaining 24 characteristics were typical markers of academic success as defined by the authors. Examples of the academic traits included: pharmacy grade point average, North American Pharmacist Licensure Examination (NAPLEX) score, and completion of a post-graduate year one (PGY1) residency.

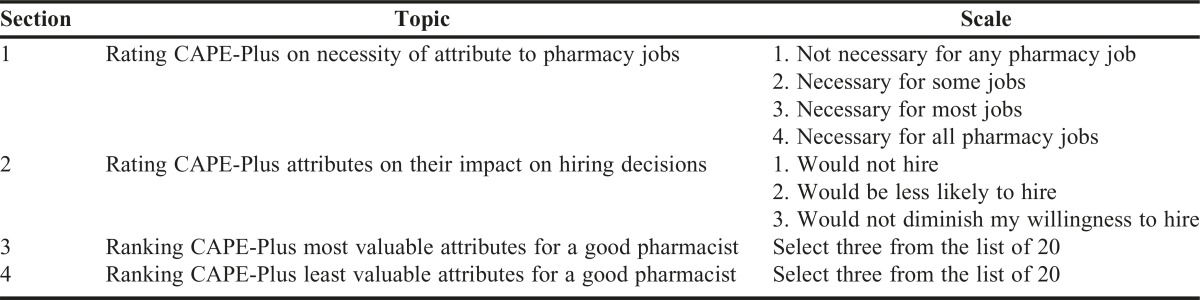

The last section dealing with the CAPE outcomes included the 15 attributes from the CAPE outcomes and an additional five business related attributes determined by the authors to be necessary to answer the research questions posed. These additional attributes were: marketer/ sales builder, business manager, producer, team builder, and business operator. The full list of 20 surveyed attributes will be referred to as CAPE-Plus for the remainder of this paper. The blueprint for the questionnaire questions and the dimensions upon which they were rated are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

The Blueprint for the Questionnaire Questions Used to Assess the CAPE-Plus Attributes’ Impact on Pharmacists Hiring for Entry-level Positions

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 21 (Chicago, IL). For all analyses, an alpha of 0.05 was considered significant. Due to the large sample size, an additional criterion of a greater than 8% difference in group favorability/ranking was used to determine “practical” significance between groups compared. Chi-square tests were used to compare the five questions dealing with the CAPE-Plus attributes to demographic characteristics.

RESULTS

The questionnaire was sent to a total of 36,817 licensed pharmacists, including 5,423 pharmacists licensed in Arkansas, 3,126 licensed in California, 14,704 licensed in North Carolina, and 13,564 licensed in Ohio. There were 3,723 total responses to the questionnaire received, producing an overall response rate of approximately 10%. Response rates were 22% for Arkansas, 5% for California, 9% for North Carolina, and 7% for Ohio.

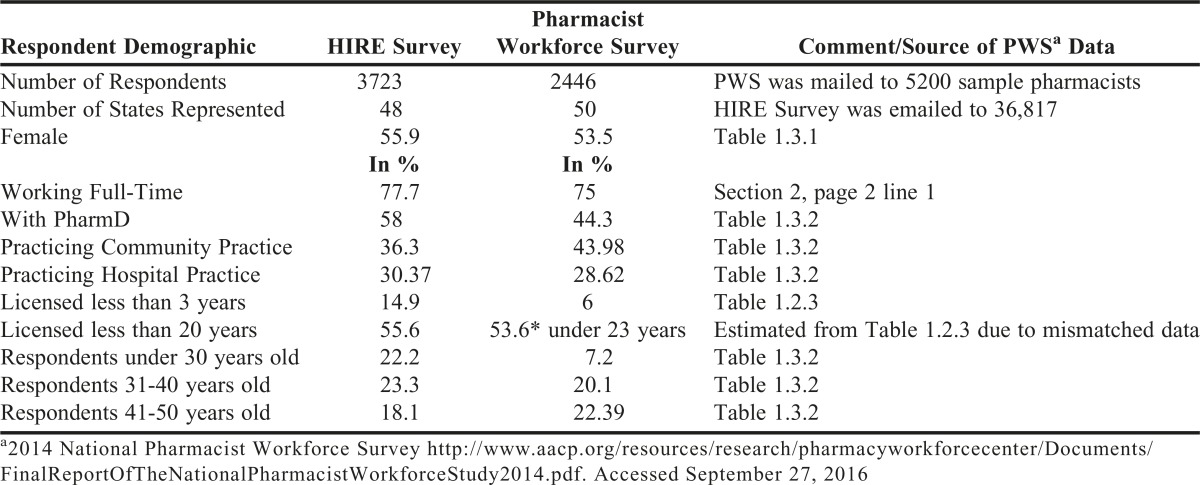

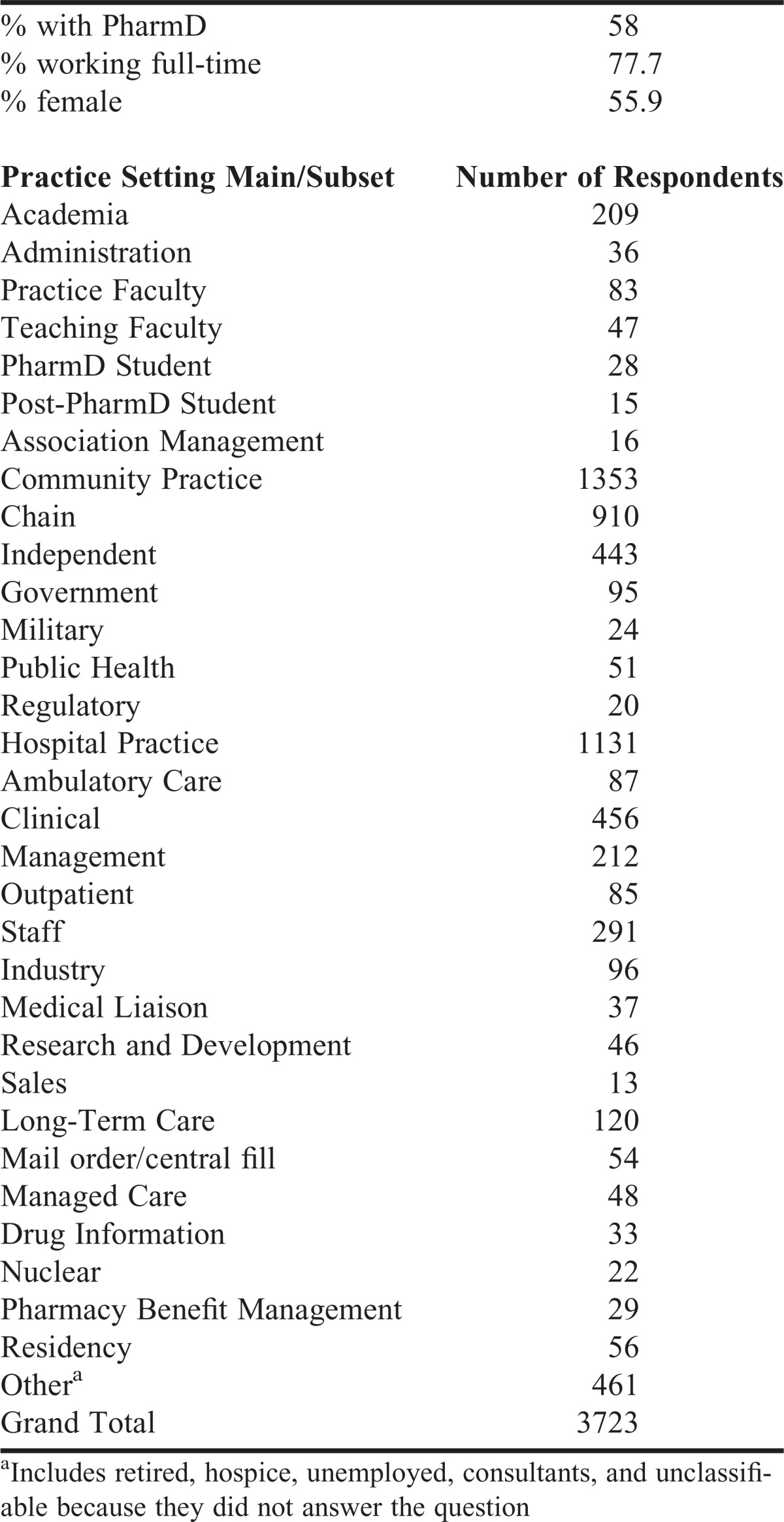

Responses were received from pharmacists living in 48 states and the District of Columbia. The two states for which no respondent reported currently living were Vermont and Rhode Island. The basic demographics of the respondent group are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographics of Respondents to the HIRE Survey 2014

In response to the question on how many pharmacists they have worked with long enough during their career to judge their professional competence, 39% of respondents selected 11-30 pharmacists, 30.4% selected 31-100 pharmacists, and less than 1% indicated that they had worked with zero pharmacists for which they could judge their professional competence. With respect to involvement in the hiring process at their current job, 33% indicated they make the decision to hire, 36% are part of hiring process, and 31% are not involved in the process. When asked how many pharmacists they had worked with who had been terminated against their will from their place of employment, 34% of respondents indicated zero, 55% indicated one to five, and 11% indicated six or more. Twenty percent of respondents indicated that they had been personally terminated against their will from a job at some point in their career.

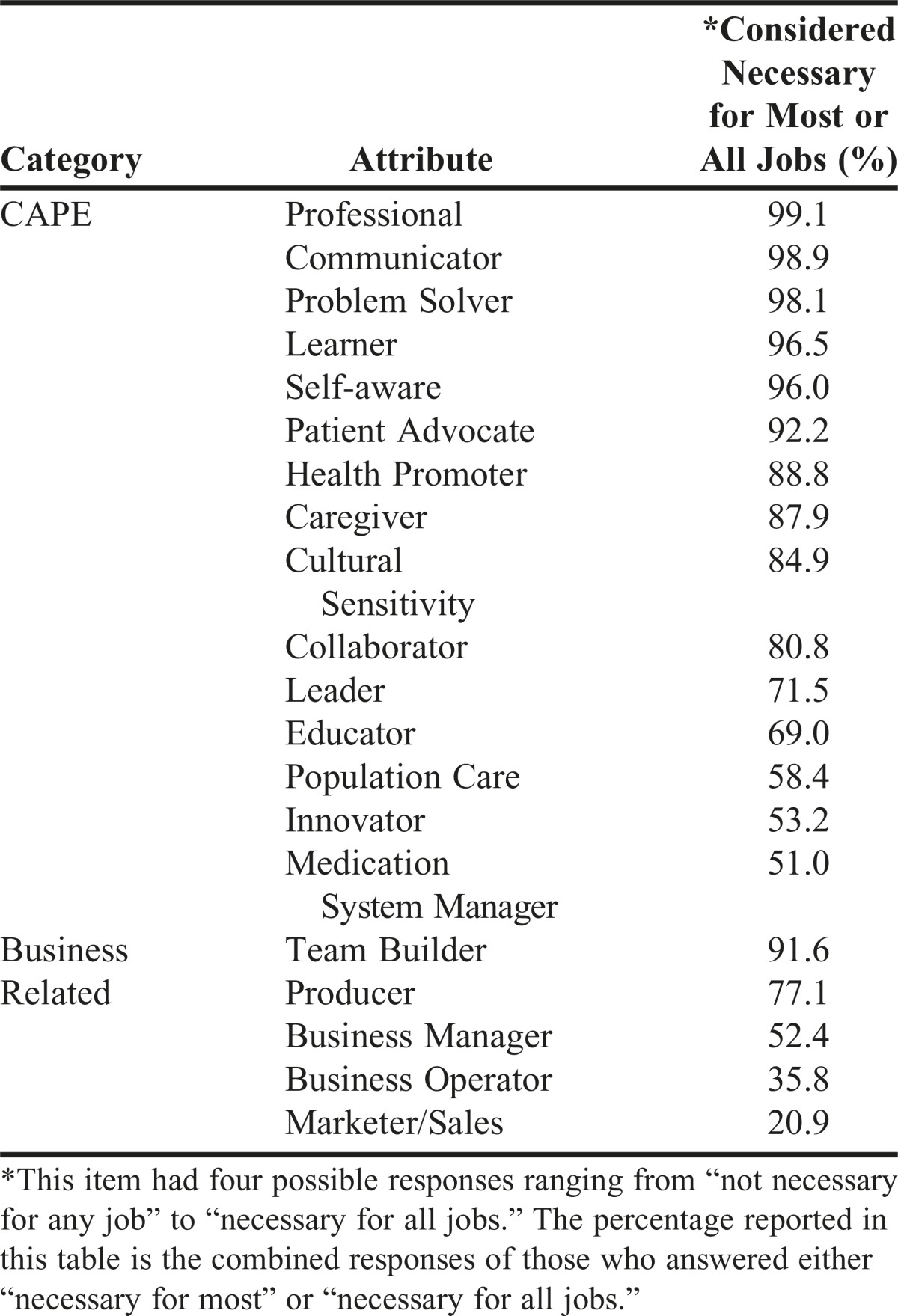

Respondents were asked to determine whether a CAPE-Plus attribute is necessary to be a good pharmacist. The four categories (not necessary for any job, necessary for some jobs, necessary for most jobs and necessary for all jobs) were collapsed into the following two major categories: “Considered Necessary for Most or All Jobs” and “Not Considered Necessary for Most or All Jobs” and sorted in descending order of the first category (Table 4). Of the CAPE-Plus attributes, 10 were ranked as being considered necessary for most or all pharmacist jobs by 80% or more of respondents, with the highest rankings given to professional, communicator, problem solver, learner, self-aware, and patient advocate attributes. Of the five non-CAPE attributes included in the CAPE-Plus list of attributes, only the team builder attribute was ranked as being considered necessary for most or all pharmacist job by 80% or more of respondents. The CAPE-Plus attributes considered necessary by 53.2% or less of the respondents were all business-related attributes such as innovator, medication system manager, manager, business operator, and marketer/sales.

Table 4.

Ratings by Respondents on Attributes Considered Necessary for Most or All Pharmacist Jobs

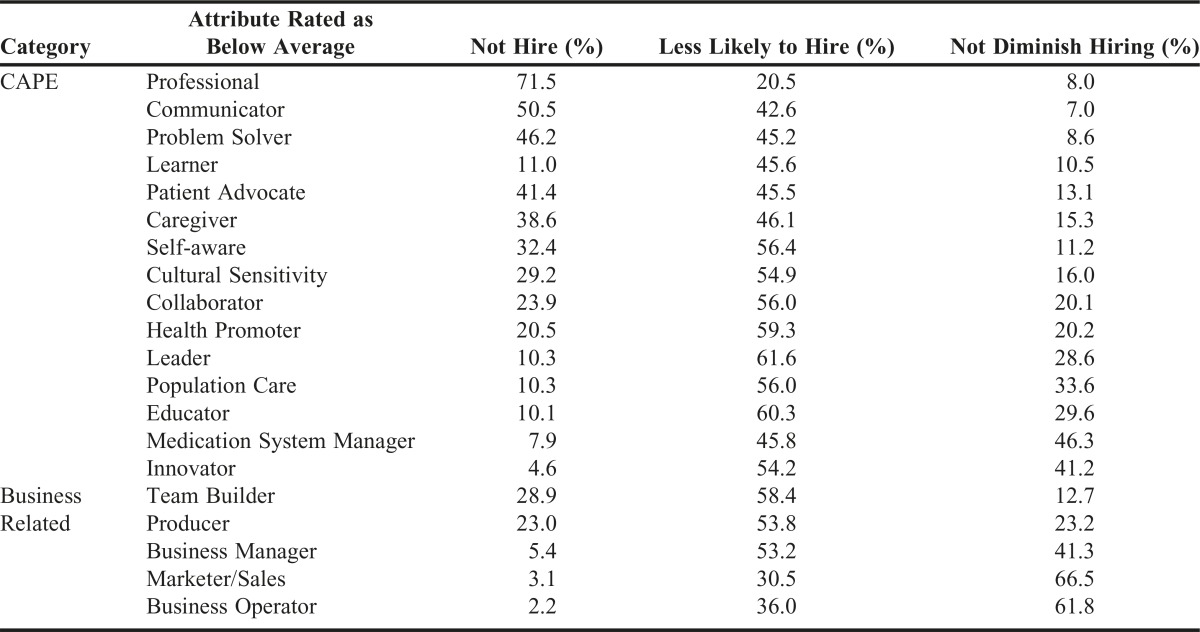

Respondents were asked to indicate the impact on hiring decisions if a candidate was determined to be below average on a CAPE-Plus attribute (Table 5). At least 50% of respondents would “not hire” or were “less likely to hire” candidates who were below average in any of the 15 CAPE Outcomes and in three of the five non-CAPE attributes. The CAPE-Plus attributes with the most positive impact (90% or higher) on hiring decisions appear to be professional, communicator, problem solver, learner, self-aware, patient advocate, and team builder. Those with the least impact on disqualifying an applicant appear to be the business skills such as medication system manager, business operator, marketing/sales, and innovator.

Table 5.

Respondents’ Indications of the Impact on Hiring Decision if a Candidate was Determined to be Below Average on an Attribute

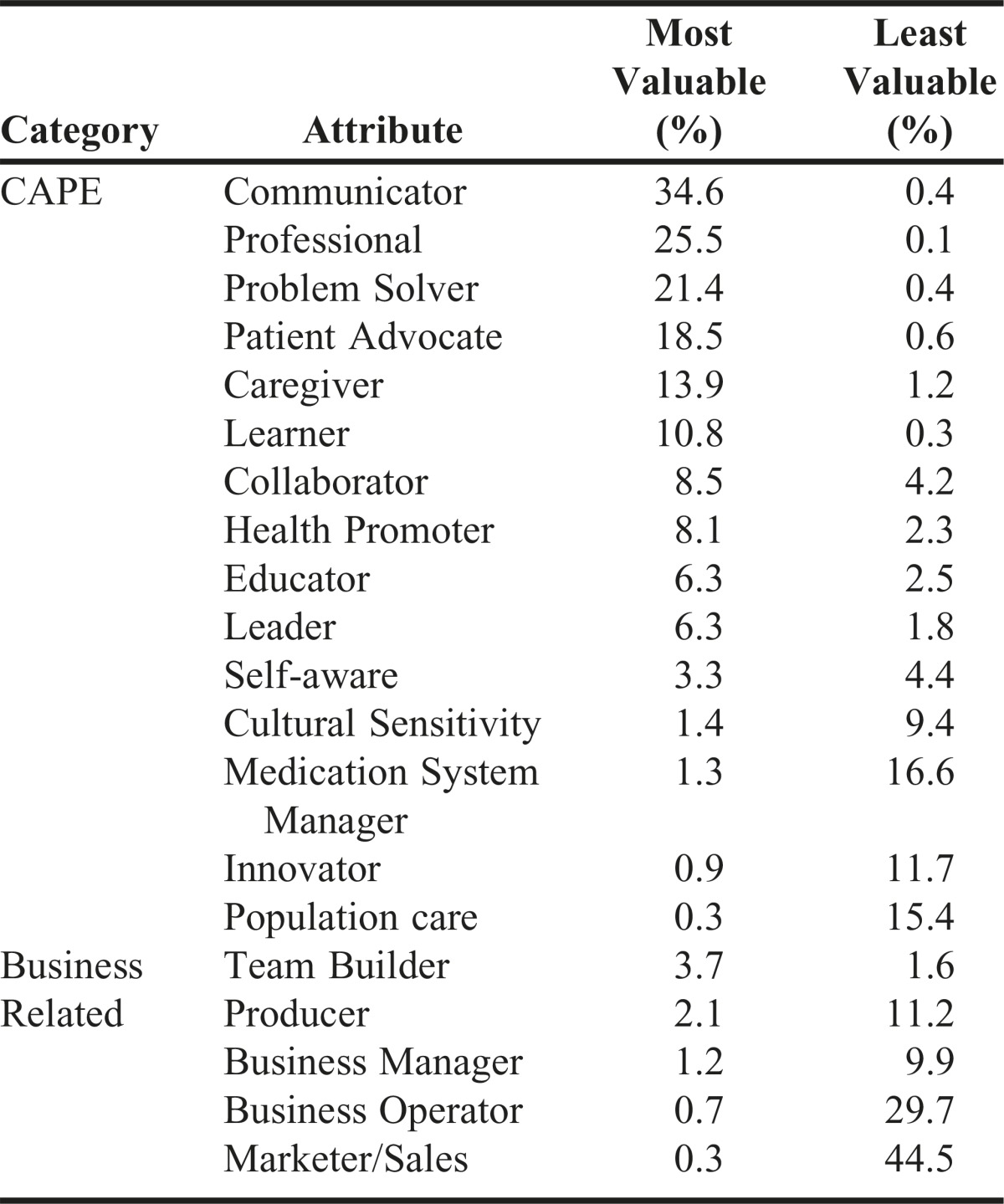

Respondents were also asked to select the three attributes that they considered the most and least valuable (Table 6). The highest rankings were given to the following attributes, in descending order: communicator, professional, problem solver, patient advocate, caregiver, and learner. The attributes ranked by less than 4% of respondents as being among the most valuable included self-aware, cultural sensitivity, medication system manager, innovator, population care, and all five non-CAPE attributes. Those attributes ranked as least valuable by at least 10% of respondents included three of the 15 CAPE Outcomes (innovator, population care, medication system) and three of the five added business-related attributes (producer, business operator, marketer/sales).

Table 6.

Percentage of Times an Attribute Was Listed as One of the Respondents’ Three Most and Least Valuable Choices

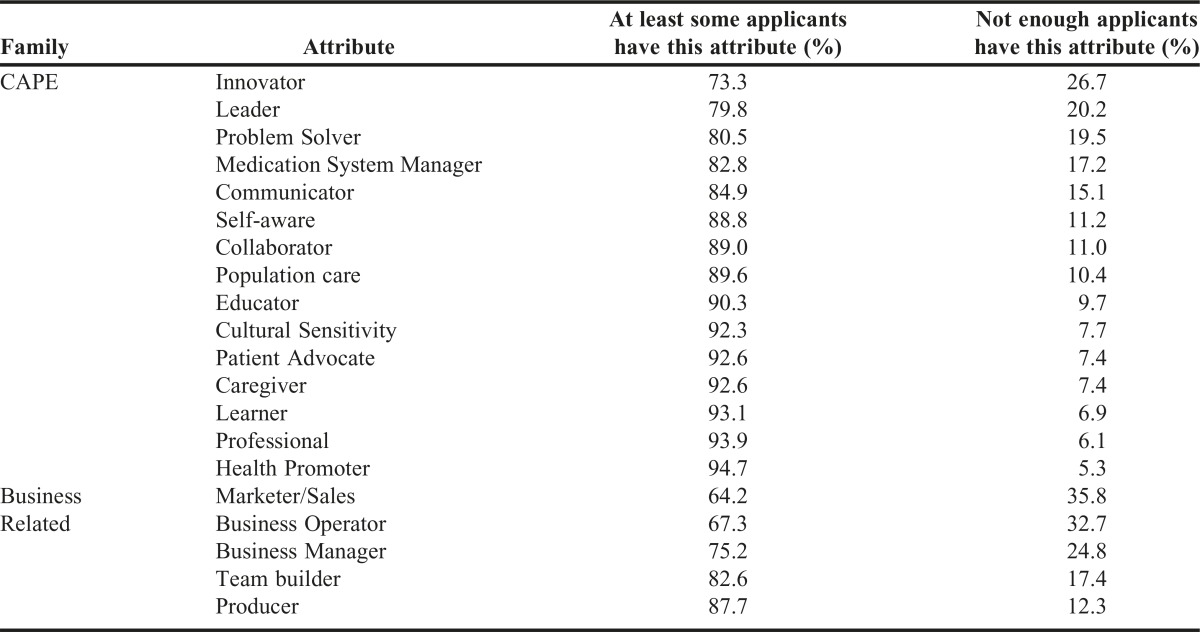

For the questionnaire item dealing with the supply of attributes within the pharmacist candidate pool, the responses indicating that every, most or some applicants having the attribute were combined into one group designated as “at least some applicants” and were compared to “not enough applicants” having the attribute (Table 7). The attributes that at least 15% of respondents considered lacking in the applicant pool include five of the 15 CAPE Outcomes (innovator, leader, problem solver, medication system manager, and communicator) and four of the five non-CAPE attributes (marketer/sales, business operator, business manager, and team builder).

Table 7.

Respondents’ Rating of Attributes as Found in at Least Some (some, most or all) Applicants or in Not Enough Applicants

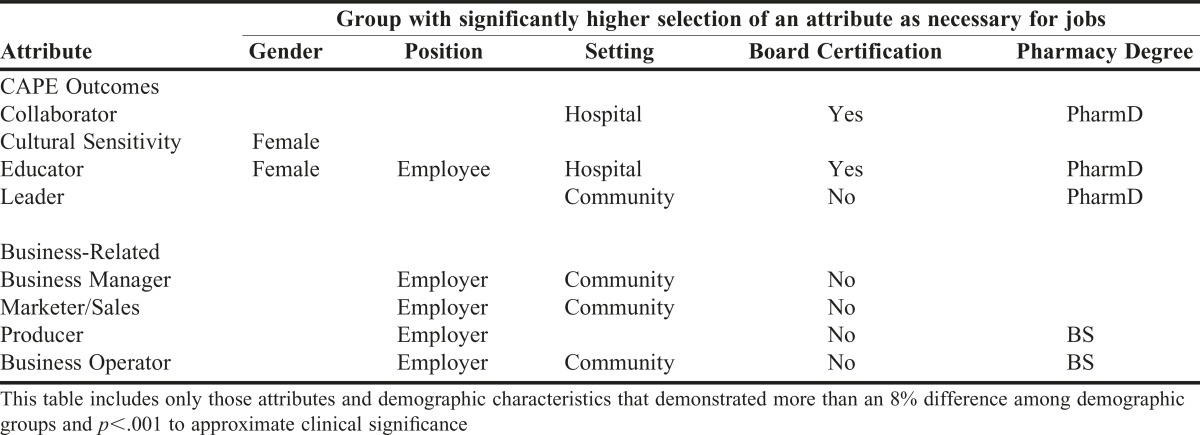

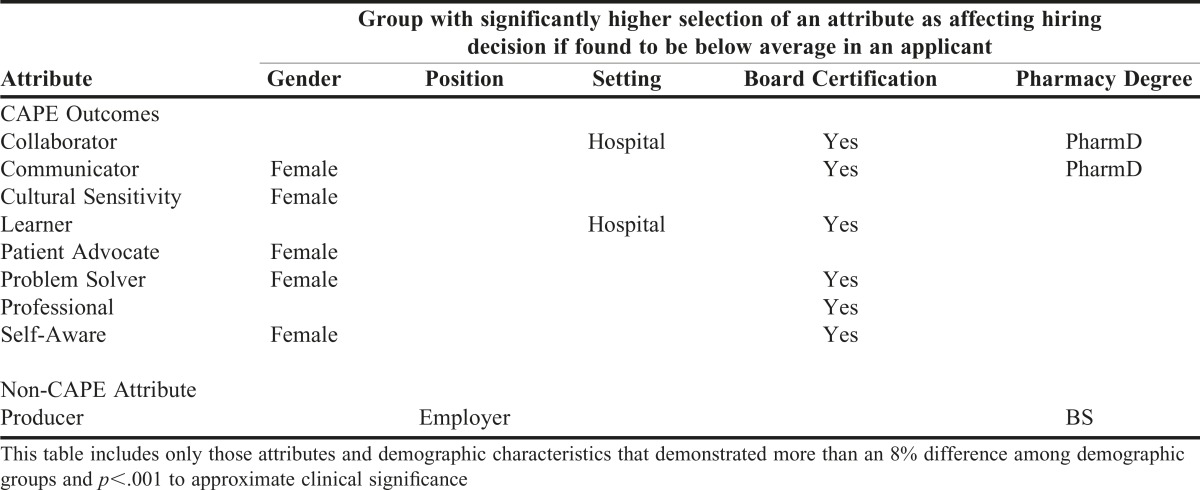

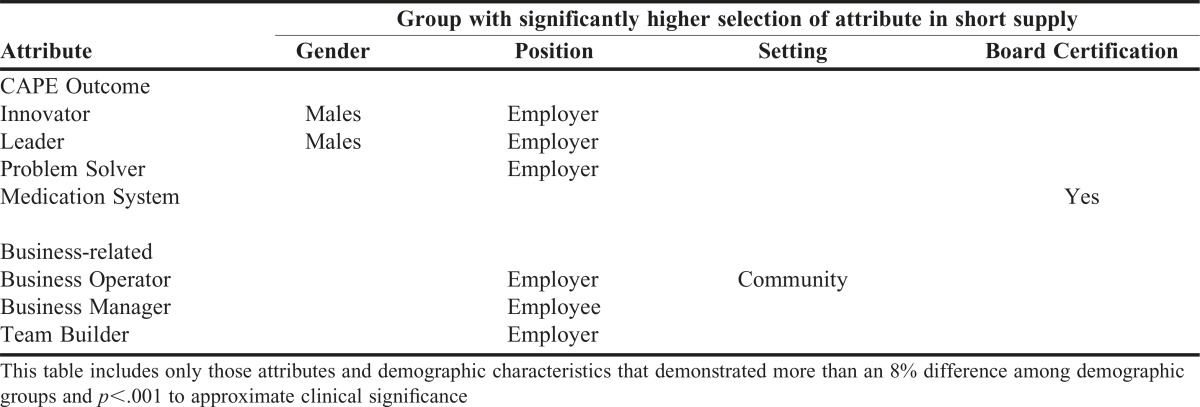

Responses to the questionnaire items on attributes necessary for pharmacist jobs, attributes that affect hiring decisions, and attribute supply in applicants were further analyzed to determine whether those responses differed by demographic characteristics (gender, position, setting, board certification, highest pharmacy degree) of the respondents (Tables 8, 9, and 10). These tables only include those attributes and those demographic characteristics that were associated with a meaningful difference, which was defined as having a difference between the demographic groups of greater than 8% and p<.001 for the attribute listed. Because of the large sample size even small differences were statistically significant. An 8% differential was used to approximate clinical significance. For example, the educator attribute was ranked as being more important as an attribute for a pharmacist job by females, employees, and those working in hospital, board certified or with a PharmD degree (compared to males, employers, and those working in non-hospital settings, not board certified, and with a bachelor of pharmacy [BPharm] degree) (Table 8). The collaborator attribute was ranked as being more important as an attribute for a pharmacist job (Table 8) and as being a factor that would impact a hiring decision if a candidate was below average in that attribute (Table 9) by those working in hospital settings, those with board certification, and those with a PharmD degree. Additionally, employers ranked business operator, innovator, leader, manager, problem solver, and team builder as attributes being most likely to be not seen in enough applicants (Table 10). The non-CAPE attributes appeared to be more highly ranked in each instance by employers (vs employees) and at times by those in the community pharmacy setting or with a BPharm degree (Tables 8, 9, and 10). Additional associations among respondent characteristics and attributes considered necessary for pharmacist jobs, important in hiring decisions, and in short supply in the applicant pool are also important and are noted in Tables 8, 9, and 10.

Table 8.

Respondent Demographic Characteristics Associated With Attributes That Were Ranked as Being Necessary for a Pharmacist Job

Table 9.

Respondent Demographic Characteristics Associated With Attributes That Would Affect Hiring Decision if Found to be Below Average in an Applicant

Table 10.

Respondent Demographic Characteristics Associated With Attributes That Were Not Seen in Enough Applicants

DISCUSSION

Because the survey response rate was only 10%, key demographic data are compared with the demographics of the 2014 National Pharmacist Workforce Study (PWS)5 to provide evidence that the respondent sample is substantially similar to the sample used to complete this widely quoted survey (Table 3). The HIRE Survey response rate was lower but the actual sample size was 52% larger. The percent of respondents who were female, licensed less than 20 years, and working full-time were within a 3% variance. And both surveys captured results from more than 1000 community practice and hospital pharmacists respectively. The HIRE survey appears to have captured more respondents who have practiced less than three years.

Table 3.

Comparison of Key Respondent Demographics Between HIRE Survey and the 2014 National Pharmacist Workforce Survey

The respondents to the questionnaire represented a wide spectrum of pharmacists based on age, gender, setting, position, certification, and highest pharmacy degree earned. Although the invitation lists were generated from only four state license rolls, respondents were from 48 states and the District of Columbia and appeared to mirror the basic age, sex, and practice setting distinctions as the widely respected PWS (Table 3).5

The development of the 2013 CAPE Outcomes and their full incorporation into ACPE Standards 2016 has provided the incentive for pharmacy programs to fully embrace the development of the CAPE Outcomes in their graduates. However, the importance and usefulness of those outcomes has not been evaluated by practicing pharmacists. Therefore, this study collected perceptions from 3,723 pharmacists on the CAPE Outcomes and select business-related attributes with respect to the following: importance as being necessary for all pharmacy jobs, importance as a factor that would impact hiring if a candidate was below average in an attribute, relative rankings of the top three most important or the three least important attributes, and whether there is a shortage of these attributes in candidates for jobs.

There were several consistencies among those attributes ranked as being most necessary for any pharmacist job and those that would adversely affect a hiring decision if an applicant was rated as below average in that attribute (Tables 4 and 5). The CAPE-Plus attributes rated highest in those two survey items included professional, communicator, problem solver, learner, self-aware, patient advocate, caregiver, and cultural sensitivity. The only business-related attribute that was rated highest on those two items was team builder. The rankings for the three most important and three least important attributes (Table 5) reconfirm that these are critical when it comes to hiring decisions. The consensus across all practice settings indicates the importance of these attributes in the hiring of pharmacists regardless of practice setting.

However, the attributes rated as not being found in enough applicants included five of 15 CAPE Outcomes (innovator, leader, problem solver, medication system manager, and communicator) and four of five non-CAPE attributes (marketer/sales, business operator, manager, and team builder) (Table 7). Given that the survey asked about hiring for an entry-level pharmacist position, schools may wish to consider the time and attention they devote to basic business skills such as the five business-related attributes surveyed.

Those rated as highly necessary for pharmacist jobs, impacting hiring decisions, but not found in enough applicants included two CAPE Outcomes (communicator and problem solver) and one business-related attribute (team builder). This information should stimulate pharmacy programs to consider methods to enhance the development of these abilities in their graduates to correct the actual or perceived deficiency in these attributes in graduates.

Perspective is very important as noted in the analyses of the associations among attributes and respondent characteristics. Pharmacists from different background or practice settings tended to value different attributes. Women were more likely than men to value cultural sensitivity, educator, communicator, patient advocate, problem solver and self-aware attributes – all of which are CAPE Outcomes. Employers were more likely to value manager, marketer/sales, producer, and business operator attributes – all of which were business-related attributes. Employees were more likely to value the educator attribute. Community pharmacists were more likely to value leader, manager, marketer/sales, and business operator attributes. Hospital pharmacists were more likely to value collaborator, learner, and educator attributes. Board certified pharmacists were more likely to value collaborator and educator attributes as being necessary for a pharmacist job, while those without board certification were more likely to value leader, manager, marketer/sales, producer, and business operator. Finally, those with a PharmD degree were more likely to value collaborator, educator, and leader attributes compared to those with a BPharm degree, who were more likely to value producer and business operator attributes. In general, these trends appear to indicate that select CAPE Outcome attributes are rated as more important by women, employees, and those in hospital pharmacy settings, with board certification, and with PharmD degrees. Select non-CAPE attributes used in this study appear to be ranked higher by employers and those in community pharmacy settings, without board certification and with BPharm degrees.

Additional trends were also remarkable. When asked to select the top three most important attributes, there was considerable spread with only four attributes being selected at least once by more than 20% of respondents. It is also interesting that given the major focus currently placed on interprofessional collaboration in education and practice settings by both ACPE Standards 20162 and the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) core competencies,6 the collaborator and team building attributes were not rated most important by practitioners.

The potential limitations of this study include the response rate, selection of the limited number of states, length of the questionnaire, potential lack of a common definition of certain attributes or other terms, and the perceptual nature of this study. The response rate varied by state from 5 to 22%, despite repeated efforts to enhance the response rate through follow-up emails. While the response rate of this questionnaire is low at 10%, the N (3,723) is large and the demographics are substantially similar to the widely respected 2014 National Pharmacist Workforce Survey. The length of the questionnaire may have led to a decreased response rate or to survey fatigue, but there is no evidence to support either of those concerns. The terms used for the CAPE Outcomes were taken directly from the 2013 CAPE Outcomes to maintain consistency. The results from this study are based on the perceptions of pharmacists. Those perceptions are felt to be reasonably accurate, but may differ from the actual importance and abilities of graduates in these attributes.

All CAPE Outcomes were rated important by at least 51% of respondents, suggesting that the subdomains chosen by the CAPE 2013 committee are all relevant to practice. However, the estimate of necessity for all jobs, the impact on hiring decisions, the forced ranking of the most important or least important three attributes, and the estimates of whether the attribute was available in the current supply of applicants all showed substantial variability. Additionally, the perspective on importance of individual attributes was influenced by the pharmacist’s demographics, position, practice setting, certification, and highest degree earned. This suggests that the pharmacist community has some variability in the importance of these attributes, most likely based on the type of practice setting or position being considered.

The results of this study serve to confirm the importance of the skills and abilities set forth by the CAPE outcomes and provide pharmacy educators with confirmation that these characteristics are important to include and reinforce in our curricula. They also provide a means for us to emphasize to our trainees that a marketable pharmacist practitioner must demonstrate not only technical knowledge, but the skills and abilities described here to compete for the jobs they want.

CONCLUSION

The results of this investigation suggest that the 15 subdomains of CAPE 2013 seem to be validated as important by the sample of pharmacists who responded to the questionnaire. However, the subdomains do not appear to be considered equally important for all jobs that pharmacists may hold. There is significant variation in the relative importance to good practice and successful hiring decisions. Pharmacy educators may wish to review this study to help them decide the proper allocation of resources and effort to appropriately develop these abilities within their graduates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 educational outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):Article 162. doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree, 2016. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- 3.The Aggregate Demand Index http://pharmacymanpower.com/summary.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2017.

- 4.KIPP. Character strengths and corresponding behaviors. http://www.kipp.org/our-approach/strengths-and-behaviors. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- 5.Gaither CA, Schommer JC, Doucette WR, Kreling DH, Mott DA. 2014 National Pharmacist Workforce Survey, 2015. https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/finalreportofthenationalpharmacistworkforcestudy2014.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- 6.Interprofessional Educational Collaborative. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: 2016 Update. https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/ipec_2016_updated_core_competencies_report.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2017.