Abstract

Objective

To assess the 5-year risk and timing of repeat stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse procedures.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study, using a nationwide database, the 2007–2014 Marketscan Commercial Claims and Encounters and Medicare Supplemental Databases (Truven Health Analytics), which contain de-identified health care claims data from approximately 150 employer-based insurance plans across the United States. We included women aged 18–84 years and used CPT codes to identify surgeries for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP). We identified index procedures for SUI or POP after at least three years of continuous enrollment without a prior procedure. We defined three groups of women based on the index procedure: 1) SUI surgery only, 2) POP surgery only, 2) Both SUI+POP surgery. We assessed the occurrence of a subsequent SUI or POP procedure over time for women < 65 years and ≥ 65 years with a median follow-up time of 2 years (IQR 1,4).

Results

We identified a total of 138,003 index procedures: SUI only n=48,196, POP only n=49,120, and both SUI+POP n=40,687. The overall cumulative incidence of a subsequent SUI or POP surgery within 5 years after any index procedure was 7.8% (95%CI: 7.6, 8.1) for women < 65 and 9.9% (95%CI: 9.4, 10.4) for women ≥ 65 years. The cumulative incidence was lower if the initial surgery was SUI only and higher if an initial POP procedure was performed, whether POP only or SUI+POP.

Conclusions

The 5-year risk of undergoing a repeat SUI or POP surgery was < 10%, with higher risks for women ≥ 65 years and for those who underwent an initial POP surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) are prevalent conditions that are often managed surgically.1–4 In fact, the lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for either SUI or POP is 20.0% by the age of 80 years.5 Unfortunately, surgery is not definitive, as the recurrence of SUI or POP may occur.6–8

The risk of reoperation after SUI or POP has been reported to be as high as 29.2%.8 However, this estimate was based on only 400 women who underwent surgery in 1995 in the Northwest region of the United States. Thus, this high reoperation rate may not be representative of current surgical practices nationally. Furthermore, the risk of reoperation was based on past surgical history versus starting with a cohort of women undergoing their initial surgery and assessing subsequent procedures and when those repeat procedures occur.

Overall, limited data exist regarding current nationwide US risks for reoperation for SUI and POP, and details regarding when these surgeries occur are needed. In addition, SUI and POP procedures are commonly performed concurrently, and the risk of reoperation may vary based on the initial procedure performed, whether SUI only, POP only or both SUI and POP. Lastly, information on age-specific rates of reoperation is not available. Collectively, these data would be a valuable asset when counseling patients. Thus, our objectives were to estimate the cumulative incidence of subsequent surgery for SUI and POP and to assess the timing of these repeat procedures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study, using 2004 to 2014 data from the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database and Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits database (copyright © 2015 Truven Health Analytics Inc. All rights reserved).10,11 These data were comprised of de-identified, adjudicated, health care claims from approximately 150 payers in the United States, and Truven Health Analytics has validated the claims and enrollment data to ensure completeness, accuracy, and reliability. These databases include individuals with commercial, employment-based insurance such as employees, their spouses, dependents, as well as retirees. In 2014, these databases included approximately 50.9 million individuals. Of note, in 2014, 55.4% of the U.S. population, or 174.4 million individuals, had employment-based insurance; thus, this database includes a significant proportion of those with employer-based insurance.12 Unique individuals can be followed over time using encrypted identification numbers, and detailed enrollment data ensure that only individuals who could generate a claim were included in the population at risk at any given time. This study was determined to be exempt from further review by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill as only de-identified data were available.

We identified index procedures by requiring a claim for a SUI or POP procedure in 2007–2014 after at least three years of continuous enrollment without a prior procedure. For SUI, we included the following current procedural terminology (CPT) codes: 57288; 51840, 51841, 58152, 57220, 51845, 57289, 51990, 51992, 58267 or 58293. For POP, we included the following CPT codes: 57200, 57210, 57230, 57240, 57250, 57260, 57265, 57268, 57270, 56810, 57284, 57285, 57423, 57267, 57282, 57283, 57280, 57425, 57106, 57107, 57109, 57110, 57111, 57112, 57120, or 58400. We also included hysterectomy as a POP surgery if there was a primary diagnosis of prolapse associated with the hysterectomy which occurred on the same date as surgery. A diagnosis of POP was based on the International Classification of Disease (ICD-9) diagnosis code of 618.x. The above codes do not include revision of mesh (CPT 57295, 57296, 57426) or removal or revision of sling (CPT 57287) as we chose to focus on repeat surgeries for SUI and POP. Women aged younger than 18 or older than 84 years were excluded due to the rare use of these procedures among children and very elderly women.

We wanted to describe the proportion of women who had been treated with urethral bulking agents (CPT 51715) prior to or around the time of their index surgery. Thus, we identified “prior bulking agent” based on one or more claims for a urethral injection that occurred within the three-year look back period prior to the index surgery and “concurrent bulking agent” based on a claim for a urethral injection within 30 days before or after to the index surgery. Women who underwent urethral bulking agents during follow-up were not counted as having a repeat SUI procedure, as it is well-accepted that repeat injections may be needed.

We defined three cohorts of women based on their claims within 30 days of their index procedure: 1) SUI surgery only, 2) POP surgery only, 2) Both SUI and POP surgery. Follow-up began 31 days after the index procedure. Repeat procedures were defined using the list of CPT and ICD-9 diagnosis codes stated above. After identifying the index procedures, we assessed the occurrence of any subsequent SUI or POP procedure over time. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate the cumulative incidence of subsequent surgery. We estimated the cumulative rate of subsequent surgery separately by index procedure for women <65 years of age and women ≥65 years in the Marketscan Commercial Claims and Encounters data and the Medicare Supplemental Coordination of Benefits data, respectively. Because the relative number of women included in the Medicare Supplemental data compared to those in the Commercial Claims and Encounters data does not reflect the true age distribution of women in the US, we chose not to report overall estimates across all age groups as this would have under-represented women > 65 in an overall estimate of the cumulative incidence of repeat surgery. Therefore, we presented the data for women < 65 and those ≥ 65 years separately.

In addition to the overall cumulative incidence of subsequent surgery, we also estimated the age-specific rates of subsequent surgery for the following age groups: 18–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, and 75–84. In order to evaluate the impact of age, US region and prior/concurrent bulking agent on subsequent surgeries, we used Cox regression analysis to adjust for these variables. We developed separate Cox models based on the type of index procedure, whether SUI only, POP only or SUI+POP.

For our primary analysis, the index surgery was based on excluding women who had had any prior SUI or POP surgery in the past three years. For our sensitivity analysis, we repeated this analysis using a 5-year look-back period, such that we evaluated women with five years of continuous enrollment and no SUI or POP procedures during that period. A longer look-back period increased the likelihood that the surgeries identified as the index procedure were truly incident (rather than repeat) procedures, the trade-off was that fewer women had five years of continuous enrollment; thus, our estimates of subsequent surgery based on these data were less precise.

RESULTS

From 2007–2014, there were 15,911,106 women 18 to 84 years of age who contributed an average of 2.67 years of follow-up for a total of 42,486,372 person-years. Among these eligible adult women, there were a total of 138,003 women who underwent an index SUI or POP surgery; the breakdown by type of index procedure was as follows: 48,196 women with SUI only, 49,120 women with POP only, and 40,687 who underwent both SUI+POP procedures. For the overall study population, the median follow-up time was 2 years (IQR 1, 4). One reason for the lower median follow-up time is that one third of the study population had their procedure performed during 2012–2014 (Table 1). Overall, the procedures were relatively equally distributed in each year of the study period from 2007–2014. A higher percentage of procedures was performed in the South and the lowest percentage was in the Northeast (Table 1). The proportion of women with a prior collagen or concurrent collagen was extremely low at < 0.5% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study population who underwent initial stress incontinence only (SUI only), pelvic organ prolapse only (POP only) or combined (SUI+POP) index procedures

| Characteristic | SUI only N=48,196 | POP only N=49,120 | SUI + POP N=40,687 | Total N=138,003 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years Follow-up, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) |

| Year | ||||

| 2007 | 10.6 | 9.7 | 10.6 | 10.3 |

| 2008 | 12.3 | 10.3 | 12.1 | 11.6 |

| 2009 | 17.3 | 13.5 | 16.2 | 15.6 |

| 2010 | 14.9 | 11.9 | 13.9 | 13.5 |

| 2011 | 15.5 | 14.0 | 14.9 | 14.8 |

| 2012 | 11.5 | 13.7 | 12.2 | 12.5 |

| 2013 | 10.7 | 15.0 | 11.5 | 12.5 |

| 2014 | 7.2 | 11.9 | 8.5 | 9.3 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–44 | 26.6 | 20.7 | 15.0 | 21.1 |

| 45–54 | 37.0 | 25.3 | 27.2 | 30.0 |

| 55–64 | 25.0 | 31.9 | 33.5 | 29.9 |

| 65–74 | 7.7 | 14.5 | 15.6 | 12.5 |

| 75–84 | 3.6 | 7.6 | 8.7 | 6.5 |

| Region | ||||

| North Central | 27.8 | 27.6 | 27.0 | 27.5 |

| Northeast | 8.5 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 8.6 |

| South | 48.1 | 46.8 | 46.8 | 47.2 |

| West | 15.7 | 16.7 | 17.9 | 16.7 |

| Prior Collagen | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Concurrent Collagen | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

Data are presented as % unless otherwise specified

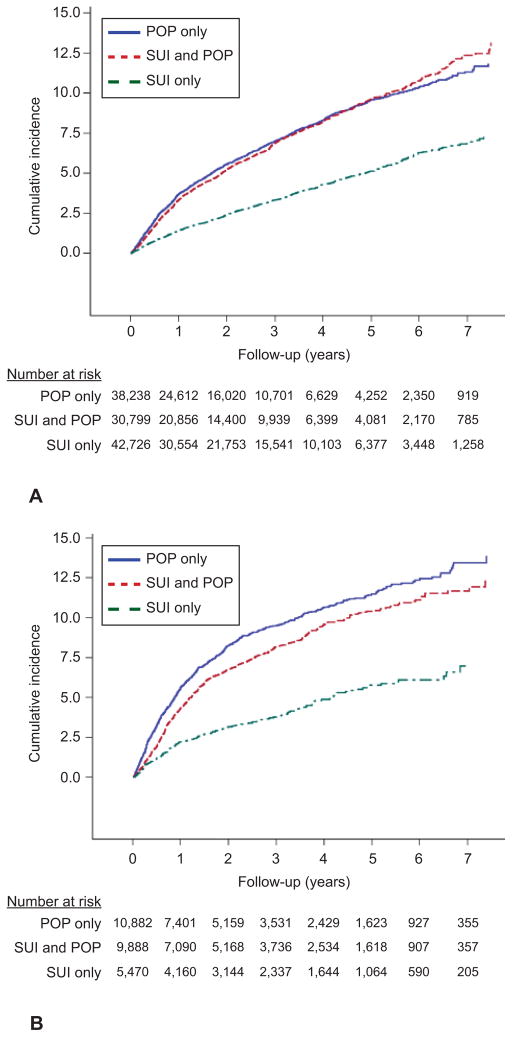

The overall cumulative incidence of a subsequent SUI or POP surgery within five years after any index procedure was 7.8% (95%CI: 7.6, 8.1) for women < 65 and 9.9% (95%CI: 9.4, 10.4) for women ≥ 65 years. The 7-year cumulative incidence of any repeat procedure was 9.9% (95%CI 9.5, 10.3) and 11.5% (95%CI 10.8, 12.2) for women < 65 and ≥ 65 years, respectively. Based on the type of index surgery, the 5-year risk of a subsequent procedure was 5.2%, 9.6%, and 9.7% after SUI only, POP only, or both SUI+POP surgeries, respectively for women < 65 years (Table 2 & Figure 1a). The 5-year estimates were higher for women ≥ 65 years at 5.9%, 11.5% and 10.5% after SUI only, POP only, or both SUI+POP surgeries, respectively (Table 2 & Figure 1b). Thus, the 5-year risk of a repeat surgery was higher if a POP surgery was performed initially, whether POP only or SUI+POP (Figures 1a & 1b). At five years, there still remained a total of 14,710 women < 65 years, with 6,377 at risk for the SUI only group, 4,252 for POP only and 4,081 for the SUI+POP group (Figure 1a). Overall, there were fewer older women ≥ 65 years who underwent POP and SUI surgery initially; thus, at five years, there were fewer older women at risk compared to younger women (Figure 1b).

Table 2.

5-year cumulative incidence with 95% confidence intervals of any subsequent procedure (SUI or POP) for women < 65 and ≥ 65 years of age based on type of index procedure (any index surgery, SUI only, POP only or SUI + POP surgery). Data using a 3-year look back period to define the index surgery or 5-year look back period are presented.

| 5-year cumulative incidence (95%CI) with 3-year look back period | 5-year cumulative incidence (95%CI) with 5-year look back period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Index Procedure | Age < 65 | Age ≥ 65 | Age < 65 | Age ≥ 65 |

| Any index procedure | 7.8 (7.6–8.1) | 9.9 (9.4–10.4) | 7.7 (7.3–8.1) | 9.7 (9.0–10.4) |

| SUI only | 5.2 (4.8–5.5) | 5.9 (5.0–6.8) | 5.0 (4.5–5.6) | 6.3 (4.5–8.8) |

| POP only | 9.6 (9.1–10.1) | 11.5 (10.7–12.4) | 9.4 (8.7–10.3) | 12.0 (10.7–13.3) |

| SUI + POP | 9.7 (9.2–10.2) | 10.5 (9.7–11.3) | 9.8 (8.9–10.7) | 9.8 (8.6–11.1) |

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of any subsequent procedure (stress urinary incontinence [SUI] or pelvic organ prolapse [POP]) over time after an index SUI only, POP only, or SUI and POP surgery for women <65 years of age (A) and women ≥65 years of age (B) with the number of women at risk in each year of follow-up based on the index surgery.

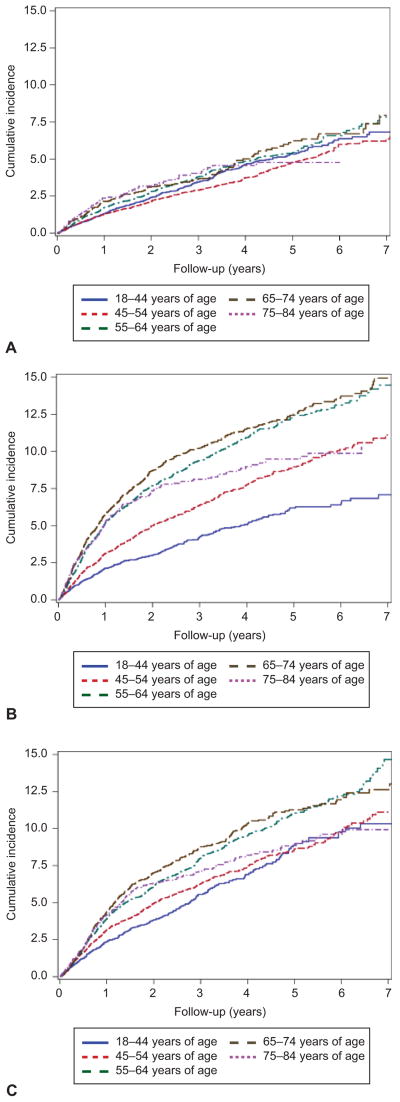

Next we evaluated the impact of age, US region and bulking agent procedures on the cumulative incidence of any subsequent SUI or POP procedure based on the type of index surgery. For SUI only, there were no differences in cumulative incidence of subsequent surgery for any age group when compared to women aged 18–44 or when different regions of the US were compared to the Northeast (Figure 2a, Table 3). For POP only, the cumulative incidence of subsequent surgery increased with each older age group when compared to the reference group of age 18–44 years and the South and West had highercumulative incidence compared to the Northeast (Figure 2b, Table 3). For SUI+POP, women aged 55–64, 65–74 and 75–84 had higher cumulative incidence of subsequent surgery compared to women aged 18–44, and there were no differences across regions of the US (Figure 2c, Table 3). Prior or concurrent bulking agents were associated with a higher rate of repeat surgery after an initial POP only procedure, but not for SUI only or SUI+POP. Due to the infrequent use of bulking agents, we were not able to assess the effects of prior and concurrent injections separately.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of any subsequent procedure (stress urinary incontinence [SUI] or pelvic organ prolapse [POP]) after an initial SUI only procedure (A), POP only procedure (B), and SUI and POP procedures (C) by age group.

Table 3.

Results of Cox regression model for any subsequent surgery after an initial SUI only, POP only and SUI+POP index procedures adjusted for age, region and prior/concurrent bulking agent.

| SUI only HR (95% CI) |

POP only HR (95% CI) |

SUI+POP HR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age 18–44 | -- | -- | -- |

| Age 45–54 | 0.89 (0.78–1.02) | 1.54 (1.35–1.76) | 1.13 (0.98–1.30) |

| Age 55–64 | 1.11 (0.96–1.28) | 2.29 (2.02–2.59) | 1.43 (1.25–1.64) |

| Age 65–74 | 1.14 (0.93–1.38) | 2.48 (2.17–2.85) | 1.53 (1.31–1.77) |

| Age 75–84 | 1.01 (0.77–1.34) | 2.00 (1.69–2.36) | 1.28 (1.07–1.53) |

| Northeast Region | -- | -- | -- |

| North Central Region | 1.16 (0.94–1.43) | 1.09 (0.94–1.27) | 1.02 (0.86–1.20) |

| South Region | 1.05 (0.86–1.29) | 1.15 (1.00–1.33) | 1.07 (0.91–1.25) |

| West Region | 1.11 (0.89–1.40) | 1.17 (1.00–1.37) | 1.07 (0.90–1.28) |

| Prior/concurrent bulking agent | 1.45 (0.92–2.28) | 2.09 (1.27–3.42) | 0.95 (0.45–2.01) |

We conducted a sensitivity analysis using a 5-year (rather than a 3-year) look-back period to define our index procedures in order to assess the robustness of our findings. With the five-year look-back period, the overall 5-year cumulative rate for any subsequent procedure was 7.7% and 9.7% for women < 65 and ≥ 65 years respectively, which were similar to the estimates using the 3-year look back (Table 2). The overall similarity of the 5-year look back results to the 3-year look back estimates affirms the robustness of our findings. The cumulative incidences based on type of index surgery for both age groups are presented in Table 2, and the 5-year and 3-year look back results based on the type of index surgery were also similar.

DISCUSSION

We found that the overall 5-year risk of a subsequent surgery for either SUI or POP was 7.8% for women < 65 years and higher at 9.9% for women ≥ 65 years within five years. Our cumulative incidence of reoperation was lower than prior US estimates, which may be due to changes in surgical practice as well as our assessment of a large nationwide cohort of women. A commonly cited article by Olsen et al. noted that the risk of reoperation was 29.2%8. This study reported on 400 women in a large health maintenance organization who underwent surgery in 1995. In contrast, we assessed a cohort of approximately 138,000 women who underwent an initial SUI or POP surgery. Even at five years of follow-up, there remained more than 14,000 women under observation in our study population for reliable estimates of the rates of repeat surgery. In addition, our repeat surgery rates may be lower as surgical practice has changed dramatically over the last 20 years,1,4 especially with the introduction of the midurethral sling for SUI.13,14

Our estimates for the cumulative incidence of reoperation for POP are consistent with data from high quality, multicenter trials from the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. In the Colpopexy and Urinary Reduction Efforts (CARE) trial, POP failure rates gradually increased during seven years of follow-up, with rates of symptomatic POP failure of 24% and 29% for the Burch urethropexy and no urethropexy groups, respectively.15 By year seven, 11/215 (5.1%) had had surgery for recurrent POP. In the Operations and Pelvic Muscle Training in the Management of Apical Support Loss (OPTIMAL) trial, 18.0% developed bothersome POP symptoms after either a sacrospinous ligament suspension or uterosacral ligament suspension, and 5.1% underwent retreatment with either a pessary or surgery by two years.16

For SUI, we previously reported on the long-term outcomes after SUI surgery with a cumulative incidence of repeat surgery of 14.5% at 9-years using data from 2000–2009. In this prior analysis, we included urethral bulking agents, which often require more than one injection.9 Thus, in the current study, we opted to not count urethral bulking agents as a repeat surgery, which likely explains the lower cumulative incidence of subsequent SUI surgery. Data from Denmark found that the risk of reoperation was 10% by five years, with the highest risk for urethral injection of 44% and the lowest risk of 6% for pubovaginal sling, retropubic midurethal slings and Burch colposuspensions.7 Rates of SUI reoperation was 3.85% at a mean follow-up of 86 months in Taiwan.17 Thus, our results regarding reoperation after an initial SUI only procedure are fairly consistent with prior studies. Repeat surgery is costly and may be more complicated, leading to higher morbidity. As the population ages 18 and the number of women undergoing SUI and POP surgery rises19, it is increasingly important to know the risk of repeat surgery, to identify those patients at highest risk for reoperations, and to accurately assess the effectiveness of various treatment options. Our study provides valuable information that will enable providers to counsel patients appropriately, allowing them to make informed and individualized decisions about their care. Recent studies on how best to assess postoperative outcomes agree on the importance of including the risk of retreatment in a composite outcome assessment.20,21 Of note, our study only focused on surgery for recurrent SUI or POP. We did not assess subsequent procedures due to mesh complications, and counseling patients regarding these potential risks is also important. 22,23

A major strength of this study is the analysis of a nationwide cohort of over 138,000 SUI and POP initial procedures which reflects recent surgical practices from 2007–2014. This cohort is substantially larger than current studies in the literature. Given our data source, we were also able to present detailed information regarding the timing of subsequent procedures and the number of women at risk at each follow-up time point. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis using a longer look-back period for identifying the initial procedure, and this analysis confirmed the robustness of our findings.

Because we analyzed claims data, we were unable to assess the impact of variables not included in the datasets such as race, comorbidities, body mass index, or smoking on the risk of subsequent procedures. In addition, our data source is comprised of individuals with employer-based insurance. Although 55% of Americans have employer-based insurance, our results may not be generalizable to those who are uninsured or underinsured.12 Our analysis also focused on the cumulative incidence of reoperation and does not represent the risk of recurrent symptoms or how often women may pursue nonsurgical options for recurrent SUI or POP, such as a physical therapy or a pessary.

Given that the lifetime risk of undergoing at least one procedure for SUI or POP is 20% 5 coupled with cumulative incidence of repeat procedures, these surgeries represent a significant public health issue. Furthermore, these estimates highlight the importance of identifying more effective long-term treatments as well as prevention strategies for these highly prevalent conditions.

PRECIS.

The 5-year risk of repeat stress incontinence or prolapse surgery is 7.8% and 9.9% for women younger than 65 and 65 years or older, respectively.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Jonsson Funk is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR001111. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.”

Footnotes

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Presented at the 36th Annual Meeting of the American Urogynecologic Society, Seattle, WA, Oct 13–17, 2015.

Financial Disclosures: Jennifer M. Wu has received grant funding from Pelvalon and Boston Scientific. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jonsson Funk M, Edenfield AL, Pate V, Visco AG, Weidner AC, Wu JM. Trends in use of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:79.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonsson Funk M, Levin PJ, Wu JM. Trends in the surgical management of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:845–51. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824b2e3e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley SL, Weidner AC, Siddiqui NY, Gandhi MP, Wu JM. Shifts in national rates of inpatient prolapse surgery emphasize current coding inadequacies. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17:204–8. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e3182254cf1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones KA, Shepherd JP, Oliphant SS, Wang L, Bunker CH, Lowder JL. Trends in inpatient prolapse procedures in the United States, 1979–2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:501.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Jonsson Funk M. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:1201–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdel-Fattah M, Familusi A, Fielding S, Ford J, Bhattacharya S. Primary and repeat surgical treatment for female pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence in parous women in the UK: a register linkage study. BMJ Open. 2011;1:e000206. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen MF, Lose G, Kesmodel US, Gradel KO. Repeat surgery after failed midurethral slings: a nationwide cohort study, 1998–2007. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:1013–9. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2925-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501–6. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonsson Funk M, Siddiqui NY, Kawasaki A, Wu JM. Long-term outcomes after stress urinary incontinence surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:83–90. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318258fbde. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Truven Health Analytics MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters Database. Source: MarketScan® is a registered trademarks of Truven Health Analytics formerly. Thomson Reuters (Healthcare) Inc; Available at: http://truvenhealth.com/markets/life-sciences/products/data-tools. Retrieved on October 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.MarketScan Data in Action: Epidemiology Studies. White paper. 2015 Available at: http://truvenhealth.com/markets/life-sciences/products/data-tools/marketscan-databases. Retrieved on October 12, 2016.

- 12.Smith JC, Medalia CUS Census Bureau. Current Population Reports, P60-253, Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2014. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, D.C: 2015. Available at: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p60-253.pdf. Retrieved on October 11, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward K, Hilton P. Prospective multicentre randomised trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ. 2002;325:67. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7355.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nilsson CG, Kuuva N, Falconer C, Rezapour M, Ulmsten U. Long-term results of the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure for surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(Suppl 2):S5–8. doi: 10.1007/s001920170003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nygaard I, Brubaker L, Zyczynski HM, et al. Long-term outcomes following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. JAMA. 2013;309:2016–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1023–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu MP, Long CY, Liang CC, Weng SF, Tong YC. Trends in reoperation for female stress urinary incontinence: A nationwide study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015;34:693–8. doi: 10.1002/nau.22648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States. Washington, D.C: U.S. Census Bureau; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu JM, Kawasaki A, Hundley AF, Dieter AA, Myers ER, Sung VW. Predicting the number of women who will undergo incontinence and prolapse surgery, 2010 to 2050. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:230.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barber MD, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al. Defining success after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:600–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b2b1ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker-Autry CY, Barber MD, Kenton K, Richter HE. Measuring outcomes in urogynecological surgery: “perspective is everything”. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:15–25. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1908-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonsson Funk M, Siddiqui NY, Pate V, Amundsen CL, Wu JM. Sling revision/removal for mesh erosion and urinary retention: long-term risk and predictors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:73.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonsson Funk M, Visco AG, Weidner AC, Pate V, Wu JM. Long-term outcomes of vaginal mesh versus native tissue repair for anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1279–85. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2043-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]