Abstract

This post hoc exploratory analysis of Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders (LIFE) trial data examines the association between the trial’s physical activity intervention and sedentary time in older adults.

Excessive sedentary time is associated with myriad negative health consequences, regardless of exercise participation, especially in older adults who accumulate the most sedentary volumes and have the highest risk of comorbidities. Furthermore, accumulating sedentary time in prolonged bouts (eg, binge television watching) exacerbates these deleterious effects. Although behavioral interventions can increase moderate-intensity activity, the transfer to sedentary behaviors remains unclear.

Methods

Institutional review boards at all sites approved the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was a post hoc exploratory analysis of the Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders (LIFE) study, a blinded randomized clinical trial conducted in 8 US centers between February 2010 and December 2013 (protocol for exploratory analysis is available in the Supplement). A moderate-intensity physical activity intervention (PA group) with a goal of 150 minutes per week of walking, in addition to strength, flexibility, and balance training, compared with a health education program (HE group) focused on elderly health, reduced the risk of major mobility disability in adults aged 70 to 89 years with mobility impairments. The PA group primarily focused on increasing overall activity levels; it did not specifically target reducing sedentary behaviors such as television viewing.

Participants were instructed to wear an accelerometer on the hip for 7 consecutive days during waking hours at baseline and 6, 12, and 24 months after randomization. Total sedentary time was defined as minutes registering fewer than 100 activity counts per minute per waking day. Total sedentary time was divided into bout lengths of 10 minutes or more, 30 minutes or more, and 60 minutes or more—each overlapping bout length represents a consecutively smaller segment of total sedentary time because longer bouts are less frequently observed. Mean differences in sedentary outcomes were estimated using linear mixed-effects modeling using the intention-to-treat approach in which participants were grouped according to randomization assignment. An α of .05 and 2-tailed alternative hypothesis testing was used for models adjusted for baseline sedentary value, age, sex, clinical site, and accelerometer wear time. Missing values were treated as missing completely at random. Accelerometer data were processed using R (R Foundation), version 3.4.0, and statistical analyses were performed using STATA (StataCorp), version 13.

Results

Of the 1635 participants, 1341 had valid accelerometer data at baseline (≥10 hours/d for ≥3 days), 669 in the PA group and 672 in the HE group. Over 24 months, 1271 had at least 1 follow-up assessment and 1164 participants had data collected at the 24-month visit. Mean age was 79 years, 67% were women, 76% were non-Hispanic white, mean body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) was 30, and 42% had a walking speed less than 0.8 m/s.

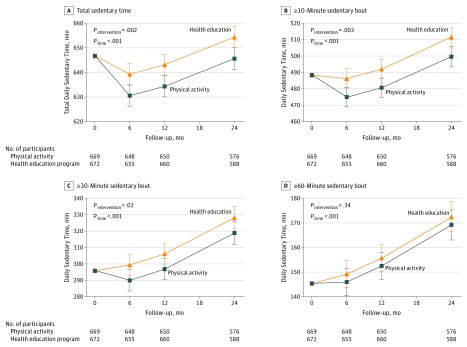

At baseline, participants wore the accelerometer for a mean of 870 minutes per day, spending 647 minutes per day in total daily sedentary time (Figure). At 6 months, the PA group accrued 630 total sedentary minutes per day and the HE group accrued 639 total sedentary minutes per day (group difference, −9 minutes [95% CI, −14 to −3]; P = .002). This difference persisted over the following 18 months (intervention × time interaction P = .61), although both groups became increasingly sedentary.

Figure. Total Daily Sedentary Time Overall and by Sedentary Bout Among Elderly Adults Receiving Physical Activity vs a Health Education Program.

All models adjusted for baseline sedentary measure, age, sex, clinical site, and accelerometer wear time. Error bars indicate 95% CIs of the predicted mean.

At baseline, participants spent a mean of 488 minutes per day in sedentary bouts of 10 minutes or more; 296 minutes per day in sedentary bouts of 30 minutes or more, and 145 minutes per day in sedentary bouts of 60 minutes or more (Figure). At 6 months, the PA group accumulated less sedentary time than the HE group in bouts of 10 minutes or more (475 minutes in the PA group vs 487 minutes in the HE group; group difference, −12 minutes [95% CI, −19 to −4]; P = .003) and bouts of 30 minutes or more (290 minutes in the PA group vs 299 minutes in the HE group; group difference, −9 minutes [95% CI, −17 to −1]; P = .02). Intervention differences were maintained over 24 months (intervention × time interaction P > .37 for both). No intervention differences were detected for bouts of 60 minutes or more. Both groups became increasingly sedentary across all bouts.

Discussion

In older adults with mobility impairments, long-term, moderate-intensity physical activity was associated with a small reduction in total sedentary time, reflected in shorter bout lengths. Limitations include the inability to detect posture, napping, behavior types (eg, television watching), and whether changes in sedentary time were clinically meaningful. Overall, traditional approaches to increasing moderate-intensity physical activity have little transfer to reductions in total sedentary time and no transfer to prolonged bouts lasting an hour or longer. Additional behavioral approaches are needed to target and reduce sedentary behaviors.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

Life Exploratory Analysis Plan

References

- 1.de Rezende LFM, Rodrigues Lopes M, Rey-López JP, Matsudo VK, Luiz OdoC. Sedentary behavior and health outcomes. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e105620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunlop DD, Song J, Arnston EK, et al. Sedentary time in US older adults associated with disability in activities of daily living independent of physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(1):93-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzgerald JD, Johnson L, Hire DG, et al. Association of objectively measured physical activity with cardiovascular risk in mobility-limited older adults. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(2):e001288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biswas A, Oh PI, Faulkner GE, et al. Sedentary time and its association with risk for disease incidence, mortality, and hospitalization in adults. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):123-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pahor M, Guralnik JM, Ambrosius WT, et al. Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of major mobility disability in older adults. JAMA. 2014;311(23):2387-2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fielding RA, Rejeski WJ, Blair S, et al. The lifestyle interventions and independence for elders study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(11):1226-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Life Exploratory Analysis Plan