Abstract

Glioblastomas are brain tumors with extensive vascularization that are associated with tumor malignancy. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) signaling pathway is activated in endothelial cell tumors, although its exact function in glioblastoma neovascularization is poorly characterized. The present study identified that endothelial cells derived from human glioblastomas exhibit increased permeability and motility compared with normal brain vascular endothelial cells. Furthermore, the phosphorylation of AKT was significantly induced in glioblastoma-derived endothelial cells and glioblastoma vessels. To the best of our knowledge, the present study demonstrated for the first time that the cell-cell adhesion junction protein Afadin is phosphorylated and re-localized in glioblastoma-derived endothelial cells, and the phosphorylation and re-localization of Afadin is PI3K/AKT pathway-dependent. AKT-mediated phosphorylation and re-localization of Afadin may be critically involved in the modulation of brain endothelial permeability and migration. Therapies targeting the PI3K/AKT/Afadin pathway may therefore be beneficial for reducing the angiogenic potential of glioblastoma.

Keywords: glioblastoma, protein kinase B signaling, Afadin, vascularization, endothelial cells

Introduction

Glioblastomas (GBMs) are brain tumors with extensive vascularization that are associated with tumor malignancy (1). Tumor vasculature is structurally and functionally abnormal, and the vessels are highly permeable, tortuous, dilated, saccular and are poorly covered by pericytes (2). Excessive blood leakage associated with vessel immaturity increases the interstitial pressure in the tumor and facilitates invasive tumor cell penetration into the circulation, allowing the metastatic spread of cancer (3). A key feature of GBMs is the extensive network of abnormal vasculature, characterized by glomeruloid structures and endothelial hyperplasia (4). Due to the location of GBM in the brain, the primary clinical problem is the edematous swelling and dramatic increase of intracerebral pressure caused by the disrupted blood brain barrier (BBB) and leaky blood vessels (5,6). A current therapeutic approach against GBMs is targeted against this vascularization process (7). Targeting endothelial cells (ECs) is a major focus of anti-vascular therapy (1). However, targeting glioma angiogenesis by vascular endothelial growth factor inhibition has only exhibited a minor effect on patient survival (8). At present, the biological characteristics of ECs in GBMs are poorly characterized, and the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the vascularization in GBMs require additional study.

Endothelial cell-cell junctions are critical for vascular integrity, EC growth, vascular development and the maintenance of vascular function (9). Endothelial junctional proteins also control multiple signaling events intracellularly via membrane proteins, clustering of signaling molecules and growth factor receptors (10). Afadin, originally identified as an actin-binding protein, is localized at adherens junctions and is expressed in epithelial cells, neurons, fibroblasts and ECs (11,12). Afadin is an adaptor protein that binds to numerous scaffolding and actin-binding proteins, and contributes to the association of immunoglobulin-like cell adhesion molecule nectins with other cell-cell adhesion molecules and intracellular signaling systems (11). Afadin has multiple functions in cell-cell adhesion and in cell movement, proliferation, survival and polarization (13). Afadin has also been demonstrated to regulate integrin-mediated cell adhesion and cell migration, although it appears that the function of Afadin in the positive or negative regulation of cell motility is context-dependent (14,15). Afadin also directly interacts with the tight junction-associated protein junction adhesion molecule-A, thereby affecting tight junction assembly during progression of the polarity program (16).

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) pathway is a complex and central regulator of a number of fundamental cellular processes (17) and regulates all phenotypes that contribute to the progression of human cancer, including GBM (17,18). The AKT pathway was previously demonstrated to be activated in EC tumors (19,20). Sustained endothelial AKT activation mediated increased blood vessel size and generalized edema caused by chronic vascular permeability (21). AKT signaling in the tumor vasculature was sensitive to rapamycin, suggesting that rapamycin may affect tumor growth in part by acting as a vascular AKT inhibitor (21). A previous study indicated that Afadin is phosphorylated by all AKT isoforms and that this phosphorylation elicits a re-localization of Afadin from the adherens junctions to the nucleus (15). The present study attempted to clarify the functions of the PI3K/AKT pathway and Afadin in the GBM tumor vasculature.

Materials and methods

Reagents

The PI3K inhibitor, LY294002 (Calbiochem; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was used at a final concentration of 10 µM. The antibodies used for immunostaining and western blotting were anti-cluster of differentiation (CD) 31 (cat. no. 910003; BioLegend, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), anti-Afadin (cat. no. ab11337; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-phosphorylated (phospho)-Afadin Ser1718 (cat. no. 5485; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), anti-AKT (cat. no. 9272; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-phospho-AKT Ser473 (cat. no. 4060; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin (cat. no. AF938; R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), anti-p-endothelial nitric oxide synthase (cat. no. 9571; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-p-ERK (cat. no. 9101; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and anti-ERK (cat. no. 4695; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.).

Isolation of primary ECs

GBM or general traumatic surgical specimens were collected in accordance with a protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of Clinical Investigation of Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China). These specimens were obtained subsequent to the procurement of written informed consent by the neurosurgical team at the Children's Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China). Surgical samples from 9 GBM patients (7 males and 2 females) were included. The median age was 9 years and the age range was between 2 and 13 years. Inclusion criteria included confirmation of a histopathological diagnosis of classic GBM by two independent pathologists (Chongqing Medical University). Pediatric patients with histopathological diagnosis of other types of tumor were excluded from the present study. Control human brain vascular ECs (HBVECs) were obtained from 5 pediatric brain traumatic cases that had not previously been diagnosed with cancer. All tissues were collected between January and November 2014. ECs were derived from GBM tissues (GBM-ECs) or general traumatic surgical specimens (HBVECs) and characterized as previously described (22). Briefly, GBM tumors or general traumatic brain tissues were disaggregated using 1-mg/ml collagenase IV (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 60 min at 37°C. Isolated cells and vessel fragments were passed through a 70-µm mesh, collected by centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and seeded into 100-mm dishes with modified M-199 medium (9.87 g/l medium M-199; cat. no. 11150059; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), 10 ml/l 100X basal medium Eagle vitamin solution (cat. no. 21010046; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 1 g/l glucose and 2.2 g/l NaHCO3 containing 20% heat-inactivated low-endotoxin fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 µg/ml neomycin, 20 U/ml nystatin and 2 mmol/l L-glutamine (complete medium), and cultured for a week at 37°C with 5% CO2. Culture medium was changed twice a week. To purify the ECs, the cultured cells were subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting for CD31-positive cells using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD31 (1:100; cat. no. 303103, BioLegend, Inc.). Cells were incubated with anti-CD31 antibody at 400 µg/ml for 30 min at 4°C at a volume of 2 µl of antibody per 105 cells. The sorted cells were then collected in EC growth medium (EGM2; Lonza Group Ltd., Basel, Switzerland), plated in 24-well tissue culture plates and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Immunocytofluorescence analysis

Cells were grown on Lab-Tek II chamber slide systems (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C, rinsed with PBS and blocked with PBS containing 5% BSA (cat. no. A2058; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 30 min at room temperature. Primary antibodies against VE-cadherin [cat. no. sc-9989; 1:100 dilution in PBS containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 (T-PBS); Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA]; cluster of differentiation (CD) 31 (cat. no. 550389; 1:200; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA); Afadin (cat. no. ab11337; 1:100; Abcam) and phospho-AKT Ser473 (cat. no. 4060; 1:300; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) were applied to the surface of the slide and incubated overnight at 4°C. The following day, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 594- or 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) [heavy and light (H+L)] or anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (cat. no. A-11037 and A-11001; 1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, cells were counterstained with DAPI (1:5,000 dilution in T-PBS; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 10 min at room temperature. Negative controls, consisting of secondary antibodies alone, were performed on each section of tissue studied. Immunofluorescence photomicrographs were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

EC low-density lipoprotein (LDL) uptake

The ability of isolated ECs to take up acetylated (Ac) -LDL was examined using Ac-LDL labeled with 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (Dil). The primary cells were seeded at an initial density of 2×105 cells/cm2. Cultures grown on Lab-Tek II chamber slide systems (cat. no. 154526, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were incubated with 15 µg/ml Dil-Ac LDL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) in EGM2 for 20 min, washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and immediately observed by inverted fluorescence microscopy using a rhodamine filter.

Permeability assay

HBVECs or GBM-ECs (2×105 cells) were seeded on Transwell filters (0.4-µm pore size, Costar; Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) in 24-well dishes and grown in EGM2 until they reached 100% confluence. For the inhibition assay, GBM-ECs were pre-incubated for 24 h in the presence of LY294002 (10 µM) or with 1 µl of dimethylsulfoxide as a vehicle control. Then, FITC-dextran (70,000 Da; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml was added to the upper chamber. At 30 min, 50 µl samples were removed from the lower chamber. The fluorescence of these samples was measured at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm using a fluorescence plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

Transwell migration assay

Cell migration was evaluated using a Transwell system (Costar; Corning Incorporated) comprised of 8-µm polycarbonate filter inserts in 24-well plates. Briefly, HBVECs and GBM-ECs (passaged 2–3 times) were harvested using trypsin in EGM2. Next, 600 ml EGM2 medium was added to the lower chambers, while 1×105 HBVECs or GBM-ECs were plated in the upper chambers in EGM2. After 4 h of incubation, cells on the bottom of the Transwell membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 37°C for 20 min and stained with 1% crystal violet at 37°C for 10 min; the non-migrating cells in the upper chamber were removed with blunt-end swabs. The membranes were washed three times with PBS and images were captured under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Finally, the level of cell migration was quantified by counting four fields of view. The mean count of triplicated chambers is presented.

Western blot analysis

HBVECs and GBM-ECs were cultured in 6-cm dishes. Proteins were extracted using 2X SDS sample buffer (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and quantified using a Bradford protein assay kit (P0006C; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The extracted proteins (30 µg/lane) were separated using 4–15% Protean® TGX™ Precast Protein gels (cat. no. 4561083; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). Proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Following blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin overnight at 4°C, the membranes were incubated with the aforementioned antibodies overnight at 4°C. anti-Afadin (1:1,000; cat. no. ab11337; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-phosphorylated (phospho)-Afadin Ser1718 (1:1,000; cat. no. 5485; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), anti-AKT (1:1,000; cat. no. 9272; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-phospho-AKT Ser473 (1:1,000; cat. no. 4060; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-p-endothelial nitric oxide synthase (1:1,000; cat. no. 9571; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and anti-p-ERK (1:1,000; cat. no. 9101; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). GAPDH (1:2,500; cat. no. 2118; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) was used as loading control. Membranes were subsequently incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (cat. nos. ab97040 and ab7090; 1:2,500; Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature. Following two membrane washes, membranes were developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride and imaged/quantified using a Sigma-Aldrich microDOC gel documentation system (cat. no. Z692557; Merck KGaA).

Statistical analysis

Independent Student's t-tests were used to determine statistical significance. Statistical tests were performed in Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). All P-values were derived from at least three independent experiments. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

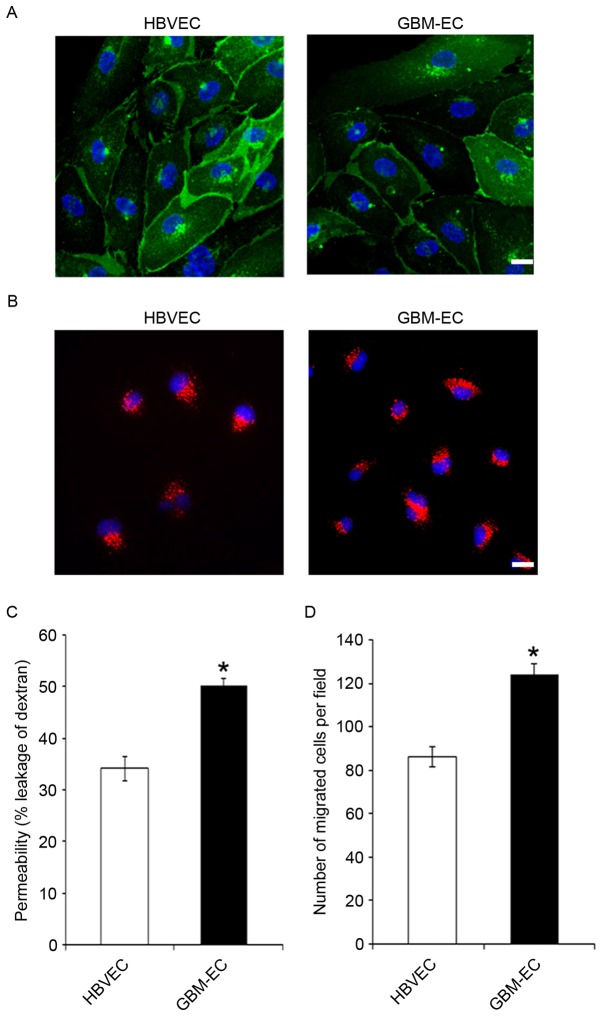

ECs isolated from human GBM tumors demonstrate increased permeability and motility

To characterize the phenotype of GBM-derived ECs, primary GBM-ECs and HBVECs were isolated from 9 and 5 patients, respectively. CD31 immunostaining (Fig. 1A) and uptake of Dil-acetylated LDL (Fig. 1B) demonstrated the purity of primary isolated brain ECs. The results indicate that these two types of ECs were positive for CD31, and that GBM-ECs exhibit a similar morphology and LDL uptake activity to HBVECs (Fig. 1A and B). Permeability of the EC barrier was assessed by comparing the transport of 70 kDa fluorescent dextran across the endothelial monolayer. HBVECs or GBM-ECs were seeded into the upper chamber of 0.4 µm Transwell filters. The degree of leakage was determined by measuring the intensity of FITC-dextran fluorescence in the lower chamber. The results demonstrate that FITC-dextran leakage was significantly increased in GBM-ECs compared with HBVECs (Fig. 1C), indicating significantly disrupted endothelial barrier function in GBMs. Cell motility is of particular interest in the design of anti-cancer therapeutics, as endothelial migration is required for tumor angiogenesis (23). Next, EC migration was evaluated using the Transwell migration assay. HBVECs or GBM-ECs were plated onto the upper chambers of an 8-µm Transwell system. Cells were allowed to migrate for 4 h through the 8-µm pores of the polycarbonate filters. As indicated in Fig. 1D, compared with HBVECs, a significantly increased number of GBM-ECs migrated to the lower side of the filter. This result demonstrated that endothelial migration is induced in GBMs.

Figure 1.

Increased permeability and motility in GBM-EC. (A) Cluster of differentiation 31 (green) immunostaining of primary isolated brain ECs from normal HBVECs and GBM-ECs. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (B) Accumulation of acetylated low-density lipoprotein (red) by primary HBVECs and GBM-ECs. (C) HBVECs and GBM-ECs were grown to confluence on Transwell filters. Permeability for FITC-dextran (70 kDa) was measured using a fluorescence plate reader (λ excitation 485 nm; λ emission 530 nm). (D) A Transwell motility assay using HBVCEs and GBM-ECs was performed using 8-µm Transwell chambers. Migrated cells were quantified by counting crystal violet stained cells in 4 random fields of view/filter. Results are the mean ± standard error of three independent experiments. Scale bars, 10 µm. *P<0.05 vs. HBVECs. HBVEC, human brain vascular endothelial cells; GBM-ECs, glioblastoma endothelial cells; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

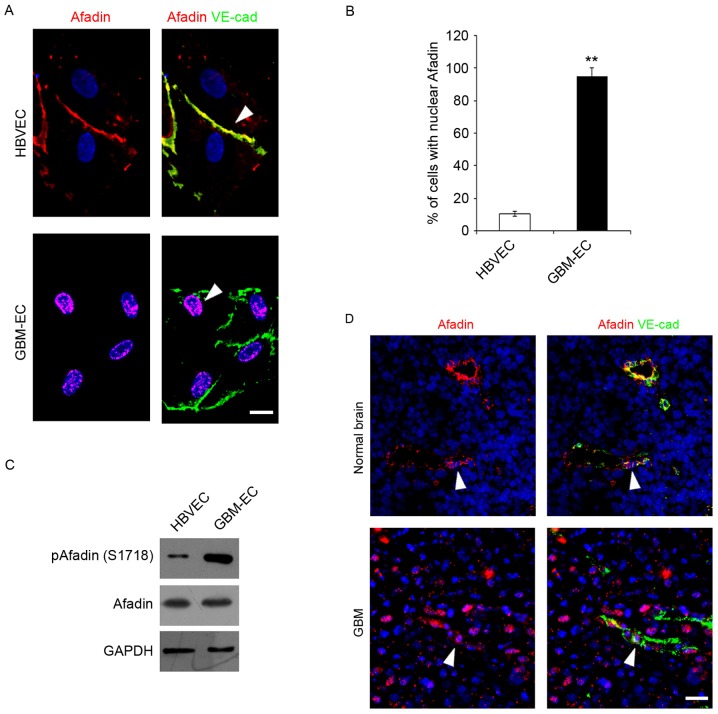

Adherens junction protein Afadin is phosphorylated and re-localized in GBM-ECs

The integrity of intercellular junctions is a major determinant of permeability of the brain endothelium (24). The adherens junction protein, Afadin, participates in the initial step of junction formation and serves a fundamental role in the regulation of cell-cell contact (25). The expression and localization of Afadin was detected in ECs Immunofluorescence microscopy indicated that total Afadin exhibited a predominantly membrane-restricted localization in HBVECs and was concentrated at the cell-cell contact sites between adjacent HBVECs, which was co-localized with a marker of endothelial cell-cell contact, VE-cadherin (Fig. 2A). However, Afadin membrane localization and its distribution along the cell borders was markedly decreased, accompanied by the appearance of its nuclear localization in GBM-ECs (Fig. 2A). Quantification of the nuclear translocation was evaluated using co-staining with DAPI and this revealed that a significantly higher percentage of GBM-ECs stained positive for nuclear Afadin compared with HBVECs (Fig. 2B). Notably, western blot analysis revealed that total Afadin protein expression did not change in GBM-ECs, while phosphorylation of Afadin at serine 1718 (Ser1718) was markedly induced in GBM-ECs compared with HBVECs (Fig. 2C). Finally, Afadin localization in human GBMs was assessed. GBM tumors and normal brain tissue obtained from archival pathology specimens were used for localization analysis and evaluated using immunofluorescence. Afadin expression in ECs was assessed by co-immunostaining for Afadin and VE-cadherin. A marked increase in the nuclear localization of Afadin in the ECs of GBM vessels compared with normal brain tissue was identified. Fig. 2D presents representative images of normal brain tissue and GBM specimens. Taken together, these results suggest that Afadin is phosphorylated and re-localized in GBM-ECs.

Figure 2.

Immunocytofluorescence analysis and western blot assay detecting phosphorylation and localization of Afadin. (A) Immunofluorescence was performed with the indicated antibodies: Afadin (red); VE-cadherin (green); and DAPI (blue). HBVECs exhibited Afadin cell junction distribution (arrow), while GBM-ECs exhibited Afadin nuclear location (arrow). Images are representative of multiple fields of view and of three independent experiments. Scale bars, 10 µm. (B) Quantification of the nuclear staining is presented in the bar graph. Error bars are the mean ± standard error. (C) Western blotting indicated the phosphorylation and expression of Afadin in HBVECs and GBM-ECs. (D) Afadin demonstrated nuclear localization in GBM vessels (arrows) as compared with cell membrane distribution in normal brain tissue (arrows). Afadin (red), VE-cadherin (green) and DAPI (blue). Representative images are presented, with scale bars, 50 µm. **P<0.01 vs. HBVECs, assessed using Student's t-test. VE-cad, vascular endothelial cadherin; HBVEC, human brain vascular endothelial cells; GBM-ECs, glioblastoma endothelial cells.

AKT pathway is activated in GBM-ECs

A previous study has indicated that the PI3K/AKT pathway serves a critical function in the pathogenesis of vasculature and BBB interruption in tumors (26). Whether the PI3K/AKT pathway is activated in human GBM-ECs was next examined. To investigate the level of AKT activation, AKT phosphorylation was analyzed using the immunofluorescence staining of human GBMs. The results demonstrated that numerous tumor ECs expressed phospho-AKT in GBMs, while quiescent vessels in the normal brain did not exhibit a high intensity of phospho-AKT (Fig. 3A). Western blot analyses of cell lysates confirmed the immunostaining results by demonstrating elevated levels of phospho-AKT, standardized to the level of total AKT, in GBM-ECs compared with HBVECs (Fig. 3B). Additionally, AKT activation was associated with the activation of downstream signaling pathways, as evidenced by the increased phosphorylation of extracellular signal-related kinase and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (Fig. 3B). These results demonstrated that the PI3K/AKT pathway is activated in GBM-ECs.

Figure 3.

Immunocytofluorescence analysis and western blot assay detecting phosphorylation of AKT. (A) Phosphorylation levels of AKT in normal brain vessels and GBM vessels. P-AKT (red), CD31 (green) and DAPI (blue). Representative images are presented. Scale bars, 100 µm. (B) Western blotting demonstrated phosphorylation levels of AKT, ERK, eNOS, and total expression level of AKT in HBVECs and GBM-ECs. p, phosphorylated; AKT, protein kinase B; CD31, cluster of differentiation; ERK, extracellular signal-related kinase; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; HBVEC, human brain vascular endothelial cells; GBM-ECs, glioblastoma endothelial cells.

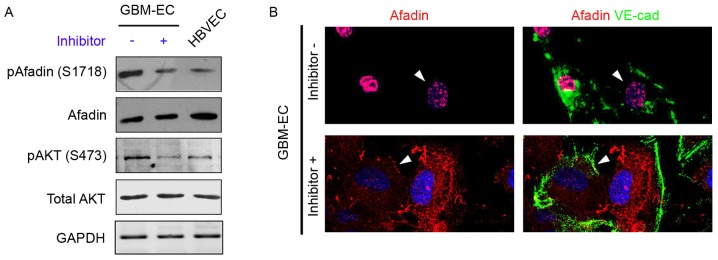

Phosphorylation and re-localization of Afadin is regulated by the PI3K/AKT pathway in GBM-ECs

A previous study demonstrated that PI3K/AKT signaling phosphorylates Afadin at Ser1718 in cancer epithelial cells (15); therefore, our group hypothesized that the induction of Afadin phosphorylation and re-localization is mediated by the PI3K/AKT pathway in GBM-ECs. To examine this hypothesis, GBM-ECs were treated with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (10 µM) for 4 h, which decreased AKT activity (Fig. 4A). The inhibition of AKT in GBM-ECs prevented the Ser1718-phosphorylation of Afadin (Fig. 4A). The effect of AKT on Afadin localization was investigated. Notably, the nuclear localization of Afadin was reversed by LY29400 treatment in GBM-ECs. Afadin protein accumulated at cell-cell junctions in LY29400-treated GBM-ECs. In contrast, Afadin accumulation was not observed at cell-cell junctions in untreated cells (Fig. 4B). The cellular localization of Afadin in the LY29400-treated GBM-ECs was in agreement with the localization observed in HBVECs.

Figure 4.

Effects of PI3K/Akt inhibition on phosphorylation and localization of Afadin. (A) Western blotting revealed the phosphorylation and expression of Afadin and AKT in LY294002 inhibitor or dimethylsulfoxide (control)-treated GBM-ECs and HBVECs. (B) Afadin (red) and VE-cad (green) double immunostaining on LY294002 inhibitor-treated GBM-ECs exhibited Afadin cell membrane and junction distribution (arrows), while control GBM-ECs exhibited Afadin nuclear location (arrows). VE-cad, vascular endothelial cadherin; HBVEC, human brain vascular endothelial cells; GBM-ECs, glioblastoma endothelial cells; p, phosphorylated; AKT, protein kinase B.

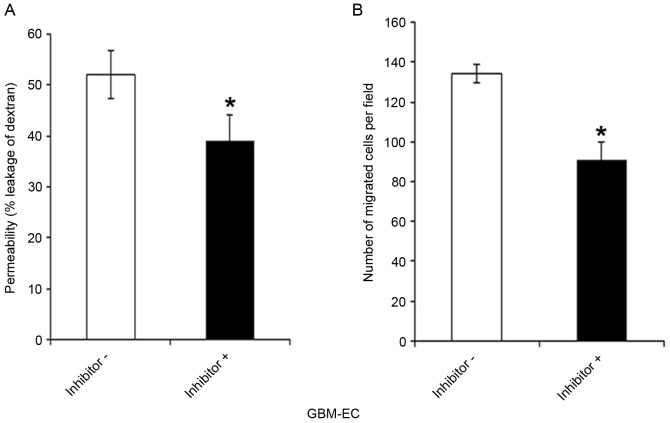

Effects of the PI3-K/AKT/Afadin pathway on the permeability and migration of GBM-ECs

Whether the PI3K/AKT/Afadin pathway regulates brain endothelial permeability and motility, which are dependent on intact adherens junctions, was next investigated. GBM-ECs were pretreated with LY294002 inhibitor or control vehicle for 4 h. LY294002 exposure significantly decreased the FITC-Dextran leakage of GBM-ECs compared with those treated with the DMSO control (Fig. 5A). As indicated in Fig. 5B, pre-treatment of cells with LY294002 inhibitors significantly reduced GBM-EC migration in the Transwell experiments. Taken together, these results suggest that the nuclear localization of Afadin and phosphorylation at Ser1718 by the AKT pathway is relevant for high permeability and pathological angiogenesis in GBM vessels.

Figure 5.

Permeability assay and Transwell migration assay. (A) GBM-ECs were pretreated with LY294002 inhibitor or DMSO as control. Then, the cells were grown to confluence on Transwell filters. Permeability for fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran (70 kDa) was measured using a fluorescence plate reader (λ excitation 485 nm; λ emission 530 nm). (B) Inhibitor or DMSO (control)-treated GBM-ECs were plated onto the upper chamber of an 8-µm Transwell system. Cells were allowed to migrate for 4 h. Migrated cells were quantified by counting crystal violet-stained cells in 4 random fields/filter. Results are presented as the mean ± standard error of 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs. negative control. GBM-ECs, glioblastoma endothelial cells; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide.

Discussion

To develop novel and effective strategies against GBMs, which are highly vascularized, it is mandatory to understand the biological characteristics of ECs in GBMs. Considering the different vascular biology of different tumors and organs, and that ECs tend to change their phenotype in response to culture conditions (27), there are significant benefits associated with the use of freshly isolated ECs from GBMs for the investigation of GBM-induced angiogenesis. In the present study, GBM-ECs were established using 9 patient-derived GBM EC cultures and HBVECs were isolated from normal brain tissues. There were no apparent differences in EC morphology between the HBVECs and GBM-ECs. However, a significantly higher permeability and a marked increase in migration of GBM-ECs compared with HBVECs were observed, indicating that ECs are abnormally activated in GBMs.

The intercellular junctions of ECs serve an important barrier function that regulates permeability to small molecules (25). Previous studies have indicated that Afadin regulates migration and cell-cell adhesion in other cell types, including fibroblasts and epithelial cells (28,29). A previous study indicated that Afadin is associated with angiogenesis through Rap1 signaling (30). The present study has demonstrated that Afadin is phosphorylated and re-localized in GBM-ECs compared with HBVECs in human brain tissues and in vitro cultures, suggesting the potential of phosphorylation and nuclear localization of Afadin as a novel marker of pathological angiogenesis in GBMs.

The PI3K/AKT pathway is a frequently unregulated pathway in cancer; with 86% of GBM clinical samples exhibiting alterations in the receptor tyrosine kinases/PI3K pathway (31,32). Furthermore, sustained endothelial activation of AKT1 has been demonstrated to induce the formation of structurally abnormal blood vessels that recapitulate the aberrations of tumor vessels (31). However, downstream mediators of AKT in brain tumor vasculatures remain poorly understood. AKT induces phosphorylation of Afadin in epithelial cells (15). However, the involvement of AKT-Afadin in angiogenesis is unknown. The present study revealed that the phosphorylation of AKT was significantly induced in GBM-ECs compared with HBVECs, indicating that the PI3K/AKT pathway is activated in GBM-ECs. Notably, to the best of our knowledge, these data demonstrate for the first time that the phosphorylation and re-localization of Afadin is PI3K/AKT pathway-dependent in human brain ECs. The inhibition of AKT by a PI3K inhibitor was revealed to prevent Ser1718-phosphorylation and the nuclear localization of Afadin in GBM-ECs.

The present study demonstrated that AKT-mediated phosphorylation and re-localization of Afadin was critically involved in the modulation of brain endothelial permeability. The pharmacological inhibition of AKT activity was associated with a decreased permeability in GBM-ECs, as evidenced by the decreased passage of 70 kDa dextran. GBM-EC migration was revealed to be downregulated by inhibition of AKT activity. Therefore, the present study has identified a function for the PI3K/AKT/Afadin pathway in the regulation of EC permeability and migration. These data on the molecular interactions of the PI3K/AKT pathway and Afadin may assist to explain an important regulatory mechanism of AKT-mediated function, including the control of EC permeability and migration.

In conclusion, the data of the present study demonstrated that AKT-mediated phosphorylation and re-localization of Afadin is an important mechanism for the regulation of GBM endothelial permeability and motility. Dysregulation of AKT activity contributes to Afadin-associated defects in vascular permeability or angiogenesis associated with GBM metastasis or chronic edema. Therefore, treatment with drugs targeting the PI3K/AKT/Afadin pathway may be beneficial in reducing the angiogenic potential of GBMs. Additional studies are required to understand how this pathway is integrated into the various signaling networks that regulate brain EC permeability and migration.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the special fund of Chongqing Key Laboratory (grant no. cstc2012gg-yyjs0838), from Chongqing Science and Technology Commission Scientific and Technological Projects, and from the Chongqing Natural Science Foundation (grant no. cstc2015jcyjBX0144).

References

- 1.Norden AD, Drappatz J, Wen PY. Antiangiogenic therapies for high-grade glioma. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:610–620. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain RK. Normalization of tumor vasculature: An emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goel S, Duda DG, Xu L, Munn LL, Boucher Y, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Normalization of the vasculature for treatment of cancer and other diseases. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:1071–1121. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00038.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang R, Chadalavada K, Wilshire J, Kowalik U, Hovinga KE, Geber A, Fligelman B, Leversha M, Brennan C, Tabar V. Glioblastoma stem-like cells give rise to tumor endothelium. Nature. 2010;468:829–833. doi: 10.1038/nature09624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolburg H, Noell S, Fallier-Becker P, Mack AF, Wolburg-Buchholz K. The disturbed blood-brain barrier in human glioblastoma. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33:579–589. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mrugala MM. Advances and challenges in the treatment of glioblastoma: A clinician's perspective. Discov Med. 2013;15:221–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerstner ER, Batchelor TT. Antiangiogenic therapy for glioblastoma. Cancer J. 2012;18:45–50. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3182431c6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pàez-Ribes M, Allen E, Hudock J, Takeda T, Okuyama H, Viñals F, Inoue M, Bergers G, Hanahan D, Casanovas O. Antiangiogenic therapy elicits malignant progression of tumors to increased local invasion and distant metastasis. Cancer cell. 2009;15:220–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bazzoni G, Dejana E. Endothelial cell-to-cell junctions: Molecular organization and role in vascular homeostasis. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:869–901. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta D, Malik AB. Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:279–367. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takai Y, Ikeda W, Ogita H, Rikitake Y. The immunoglobulin-like cell adhesion molecule nectin and its associated protein afadin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:309–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandai K, Nakanishi H, Satoh A, Obaishi H, Wada M, Nishioka H, Itoh M, Mizoguchi A, Aoki T, Fujimoto T, et al. Afadin: A novel actin filament-binding protein with one PDZ domain localized at cadherin-based cell-to-cell adherens junction. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:517–528. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogita H, Rikitake Y, Miyoshi J, Takai Y. Cell adhesion molecules nectins and associating proteins: Implications for physiology and pathology; Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci; 2010; pp. 621–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su Li, Hattori M, Moriyama M, Murata N, Harazaki M, Kaibuchi K, Minato N. AF-6 controls integrin-mediated cell adhesion by regulating Rap1 activation through the specific recruitment of Rap1GTP and SPA-1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15232–15238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elloul S, Kedrin D, Knoblauch NW, Beck AH, Toker A. The adherens junction protein afadin is an AKT substrate that regulates breast cancer cell migration. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12:464–476. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takai Y, Nakanishi H. Nectin and afadin: Novel organizers of intercellular junctions. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:17–27. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arcaro A, Guerreiro AS. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in human cancer: Genetic alterations and therapeutic implications. Curr Genomics. 2007;8:271–306. doi: 10.2174/138920207782446160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDowell KA, Riggins GJ, Gallia GL. Targeting the AKT pathway in glioblastoma. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:2411–2420. doi: 10.2174/138161211797249224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keunen O, Johansson M, Oudin A, Sanzey M, Rahim SA, Fack F, Thorsen F, Taxt T, Bartos M, Jirik R, et al. Anti-VEGF treatment reduces blood supply and increases tumor cell invasion in glioblastoma; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2011; pp. 3749–3754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phung TL, Ziv K, Dabydeen D, Eyiah-Mensah G, Riveros M, Perruzzi C, Sun J, Monahan-Earley RA, Shiojima I, Nagy JA, et al. Pathological angiogenesis is induced by sustained Akt signaling and inhibited by rapamycin. Cancer cell. 2006;10:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhai X, Liang P, Li Y, Li L, Zhou Y, Wu X, Deng J, Jiang L. Astrocytes regulate angiogenesis through the Jagged1-mediated notch1 pathway after status epilepticus. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:5893–5901. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eccles SA. Parallels in invasion and angiogenesis provide pivotal points for therapeutic intervention. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:583–598. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041820se. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dejana E, Tournier-Lasserve E, Weinstein BM. The control of vascular integrity by endothelial cell junctions: Molecular basis and pathological implications. Dev Cell. 2009;16:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallez Y, Huber P. Endothelial adherens and tight junctions in vascular homeostasis, inflammation and angiogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:794–809. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Posada-Duque RA, Barreto GE, Cardona-Gomez GP. Protection after stroke: Cellular effectors of neurovascular unit integrity. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:231. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudley AC. Tumor endothelial cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006536. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Severson EA, Lee WY, Capaldo CT, Nusrat A, Parkos CA. Junctional adhesion molecule a interacts with afadin and PDZ-GEF2 to activate Rap1A, regulate beta1 integrin levels and enhance cell migration. Mol Biolo Cell. 2009;20:1916–1925. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fournier G, Cabaud O, Josselin E, Chaix A, Adélaïde J, Isnardon D, Restouin A, Castellano R, Dubreuil P, Chaffanet M, et al. Loss of AF6/afadin, a marker of poor outcome in breast cancer, induces cell migration, invasiveness and tumor growth. Oncogene. 2011;30:3862–3874. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tawa H, Rikitake Y, Takahashi M, Amano H, Miyata M, Satomi-Kobayashi S, Kinugasa M, Nagamatsu Y, Majima T, Ogita H, et al. Role of afadin in vascular endothelial growth factor-and sphingosine 1-phosphate-induced angiogenesis. Cir Res. 2010;106:1731–1742. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.216747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karar J, Maity A. PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in angiogenesis. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4:51. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prasad G, Sottero T, Yang X, Mueller S, James CD, Weiss WA, Polley MY, Ozawa T, Berger MS, Aftab DT, et al. Inhibition of PI3K/mTOR pathways in glioblastoma and implications for combination therapy with temozolomide. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13:384–392. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]