Abstract

Current uncertainty for the future of the health care landscape is placing an increasing amount of pressure on leadership teams to be prepared to steer their organization forward in a number of potential directions. It is commonly recognized among health care leaders that culture will either enable or disable organizational success. However, very few studies empirically link culture to health care-specific performance outcomes. Nearly every health care organization in the US specifies its cultural aspirations through mission and vision statements and values. Ambitions of patient-centeredness, care for the community, workplace of choice, and world-class quality are frequently cited; yet, little definitive research exists to quantify the importance of building high-performing cultures. Our study examined the impact of cultural attributes defined by a culture index (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88) on corresponding performance with key health care measures. We mapped results of the culture index across data sets, compared results, and evaluated variations in performance among key indicators for leaders. Organizations that perform in the top quartile for our culture index statistically significantly outperformed those in the bottom quartile on all but one key performance indicator tested. The culture top quartile organizations outperformed every domain for employee engagement, physician engagement, patient experience, and overall value-based purchasing performance with statistical significance. Culture index top quartile performers also had a 3.4% lower turnover rate than the bottom quartile performers. Finally, culture index top quartile performers earned an additional 1% on value-based purchasing. Our findings demonstrate a meaningful connection between performance in the culture index and organizational performance. To best impact these key performance outcomes, health care leaders should pay attention to culture and actively steer workforce engagement in attributes that represent the culture index, such as treating patients as valued customers, having congruency between employee and organizational values, promoting employee pride, and encouraging the feeling that being a member of the organization is rewarding, in order to leverage culture as a competitive advantage.

Keywords: culture, employee engagement, patient experience, value-based care, HCAHPS, physician engagement

Video abstract

Introduction

There is a common colloquialism that culture eats strategy for lunch; yet, few studies have concretely identified cultural attributes or linked culture to producing outcomes in health care.1 Many definitions of and perspectives on culture exist, ranging from complex theory to simple articulations such as “the way things are around here”.1–4 After reviewing many positions and definitions of culture, we propose a working definition of culture to guide our research: Culture is an integrated system of learned patterns of behavior, ideas, and products that result in shared philosophies, values, assumptions, beliefs, and attitudes that knit the organizational members together and define the characteristics of everyday life.

Most employees have personally experienced, at various points across their career, the difference between feeling engaged and disengaged within their organization’s culture.5 The sheer magnitude of the complexity of the health care environment requires a constant focus on producing the very best outcomes. Organizational mission and vision statements are likely the single biggest stake in the ground for the cultural aspirations of each organization.6 Rarely do we see organizations strive for mediocrity. Instead, mission, vision, and value declarations create inspiration to point the workforce toward creating environments that heal, serve the community, educate, research, provide leading edge quality, and more.

Stubblefield stated that “Culture will drive strategy or culture will drag strategy”.2 The Baldrige Performance Excellence Program and Just Culture are two examples of frameworks for organizations to leverage their culture to improve organizational performance.7–9 Since most senior teams create accountability for translating their mission and vision into execution via a balanced scorecard and organizational goals, we wanted to understand the interconnected nature of key outcome measures and learn the role that culture can play in driving outcomes.10,11

Background/review of literature

Culture and workforce engagement in health care are intuitively linked to creating environments of patient-centered care. However, there is insufficient research pointing to demonstrable outcomes associated with high-performing cultures and engaged employees on key health care outcome metrics, including safety, patient experience, physician engagement, and value-based purchasing (VBP). We have uncovered several studies that document the interplay among key metrics.

Patient experience

It is fair to say there is room for America’s hospitals and health systems to improve the patient experience. The Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS), the nationwide hospital survey, was implemented in 2006 by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Intended to increase hospital accountability and incentives for quality improvement across the country, the survey gives an “apples to apples” comparison of patients’ perspectives on inpatient hospitalizations.12 According to the Hospital Compare website, only 72% of patients report receiving the best possible care during their hospital stay as measured by the HCAHPS survey.13 To improve transparency, in 2015, CMS launched a Star Program assigning a star rating between one and five stars. In the most recent CMS Hospital Compare release (October 2016) of Star Ratings, there are only 177 out of 4,818 hospitals with five stars.14 Emerging research is shedding light into the connection between patient experiences and quality outcomes. For instance, researchers found statistically significant associations between higher star ratings and lower rates of in-hospital complications, as well as lower rates of unplanned 30-day readmissions to the hospital.15 However, our team could not pinpoint specific research quantifying the connection between an organization’s culture and the patient experience.

Employee engagement

While academics and leaders largely agree that engaged employees have advanced levels of organizational commitment and alignment with their organization and roles, understanding a clear definition of employee engagement in health care is relatively limited.16–18 Systematic reviews of engagement definitions have yielded themes representing employee engagement including: employee support to help the organization succeed, degree of enthusiasm for work, discretionary effort, and a positive relationship between an employee and the mission of the organization.19 More studies have focused on understanding nurse engagement and the linkages to safety and turnover.20 For the purposes of our study, we established a working definition of employee/workforce engagement as an individual’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioral connection with an organization’s mission, vision, and values.

Physician/provider engagement

Similar to employee engagement, physician and provider engagement is typically measured via a questionnaire administered to the workforce. The topics of provider engagement and in particular burnout have increasingly become a part of dialogue by providers and physician/administrative leaders. A 2015 study documented that 46% of physicians reported experiencing burnout (up from 40% in 2013).21 Physician engagement is also cited as a top challenge to improve quality objectives.22 According to a study by Gallup, fully engaged and engaged physicians gave the hospital an average of 3% more outpatient referrals and 51% more inpatient referrals than physicians who were not engaged or who were actively disengaged. Engaged physicians were 26% more productive than their less engaged counterparts, which amounts to an additional $460,000 on average in patient revenue per physician per year.23 Additionally, physician engagement may influence patient compliance and outcomes, as a 2013 study found that patients were much more likely to take their prescribed medications when they were cared for by doctors who are satisfied with their jobs and lives.24

Value-based purchasing

The US health care system exhausts 17% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) – exceeding the expenditures of any other developed country. Due to factors including the high and growing costs of health care, as well as lower than expected quality outcomes, public and private payers are increasingly shifting to value-based payment models.25 Presently, many indicators demonstrate that health care organizations will become increasingly accountable to performance measures. CMS has outlined goals that by 2018, 50% of Medicare payments and 90% of Medicare Fee For Service payments will be tied to performance with value and quality measures.26

According to CMS, VBP financially incentivizes hospitals and health systems for the value of the care provided. In 2016, the VBP program withheld 1.75% of base operating diagnosis-related group payments to hospitals. Hospitals had the opportunity to earn back up to 3.5% based on their total performance score, which is comprised of four domains (Table 1): patient experience of care, clinical process of care, efficiency, and outcomes.27,28

Table 1.

Value-based purchasing FY2016 domains and measures

| Domain | Measures included |

|---|---|

| Patient experience of care | HCAHPS domains: communication with nurses, communication with doctors, responsiveness of hospital staff, hospital cleanliness and quietness, pain management, communication about medicines, discharge information, overall rating of hospital; consistency |

| Clinical process of care | Fibrinolytic therapy received within 30 minutes of hospital arrival, influenza immunization, initial antibiotic selection for community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent patients, prophylactic antibiotic selection for surgical patients, prophylactic antibiotics discontinued within 24 hours after surgery end time, urinary catheter removal on postoperative day 1 or 2, surgery patients on a beta-blocker prior to arrival who received a beta-blocker during the perioperative period, surgery patients who received appropriate venous thromboembolism prophylaxis within 24 hours prior to surgery to 24 hours after surgery |

| Efficiency | Medicare spending per beneficiary |

| Outcomes | 30-day mortality for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia, complication/patient safety for selected indicators, catheter-associated urinary tract infection, central line-associated blood stream infection, and surgical site infection for colon and abdominal hysterectomy |

Note: Data adapted from Wheeler.28

Abbreviation: HCAHPS, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems.

Turnover

Health care turnover (or retention as the inverse of turnover) is often cited as a key balanced scorecard metric and organizational challenge for health care leadership teams.29 Typically defined as the percentage of employees/providers leaving voluntarily or involuntarily in a given time period. Some studies have linked employee and provider turnover to patient experience of care.30 Nurse turnover has also been linked to quality and patient safety.9 Additionally, there is an economic consequence of turnover in terms of replacing staff members who have left the organization. As a case in point, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation estimates the average cost of replacing one nurse between $22,000 and $64,000.31 Some estimates evaluate the cost of turnover on health care between $10,696 and $18,178 per employee.32

Methodology

Each year, HealthStream surveys various people from the health care community: employees, physicians/providers, and patients. We have nationally representative databases and statistically validated surveys allowing benchmarking for employee engagement, patient experience, and physician engagement. Our research team sought to test the impact of culture on these outcome measures, along with VBP and turnover. Due to the size and magnitude of our national databases, we are able to map hospital results across various data sets, compare results, and evaluate performance variations.

One way of comparing is through national percentile rankings. The percentile indicates a hospital’s relative position within a benchmark group in terms of the percentage of hospitals it scores higher than (ranging from the 1st to the 99th percentile). For example, a hospital that is ranked at the 80th percentile of the HealthStream Database for a given measure indicates that this hospital has received a score that is higher than the scores of 80% of the hospitals within the HealthStream Database.

Measuring culture

Based on a review of health care mission statements and studies of health care organizations who have won the Malcolm Baldrige Award, we selected the following items to create a culture index measured through self-reported employee feedback from the HealthStream Employee Engagement Survey:

The extent to which patients are treated as valued customers.

You find that your values are very similar to the values of this organization.

You feel that being a member of this organization is very rewarding.

You are proud to be a part of this organization.

We confirmed the integrity of the culture index using the Cronbach’s alpha test, which measures internal consistency, that is, how closely related a set of items are as a group. It is considered to be a measure of scale reliability. The four-item culture index appears to have good internal consistency, α = 0.88. This score gave our team confidence that these four items measure the same construct of culture.

We then examined hospital level data by comparing those in the top quartile of the database (84 organizations) and the bottom quartile of the database (81 organizations) against metrics for employee engagement, physician engagement, patient experience, value-based purchasing, and turnover.

Findings

Employee engagement

Organizations performing in the top quartile for the culture index outperformed the bottom quartile in every domain of our HealthStream Employee Engagement Survey database with statistical significance (Table 2). Organizations in the top quartile for culture performed above the top 25% of hospitals in every domain – except your immediate supervisor and in the top 15% of the database in the following domains: quality and competence, organizational engagement.

Table 2.

Comparisons of culture index top and bottom quartile performers and national ranking performance on employee engagement survey domains

| HealthStream Employee Engagement Survey | Top quartile, n = 30,817a | Bottom quartile, n = 44,855a | Difference in national ranking | Cronbach’s alpha reliability | Significance testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Your immediate supervisor | 73 | 14 | 59 | 0.945 | t = 48.12, p < 0.01b |

| Pay and benefits | 79 | 10 | 69 | 0.764 | t = 80.75, p < 0.01b |

| Hiring, promotion, and opportunity | 83 | 7 | 76 | 0.903 | t = 98.71, p < 0.01b |

| Upper management | 83 | 5 | 78 | 0.956 | t = 105.30, p < 0.01b |

| Quality and competence | 86 | 5 | 81 | 0.851 | t = 86.66, p < 0.01b |

| Job engagement | 78 | 12 | 66 | 0.895 | t = 46.12, p < 0.01b |

| Organizational engagement | 89 | 6 | 83 | 0.923 | t = 96.60, p < 0.01b |

| Outcomes | 88 | 4 | 84 | 0.931 | t = 113.94, p < 0.01b |

Notes:

n = number of employees in the HealthStream Employee Engagement Survey database responding from hospitals in the top and bottom quartiles of the culture index.

Differences are statistically significant at the level noted.

Physician engagement

We then compared the top and bottom quartile culture index performers against our HealthStream Physician Engagement Survey database (Table 3). Those organizations in the top quartile for culture outperform those in the bottom quartile for every physician engagement domain with statistical significance; most domains outperform those in the bottom quartile by three to four times according to national ranking (the only exceptions being Admission and Discharge Process and Medical Records and Clinical Information).

Table 3.

Comparisons of culture index top and bottom quartile performers and national ranking performance on physician engagement survey domains

| HealthStream Physician Engagement Survey | Top quartile, n = 1,278a | Bottom quartile n = 2,791a | Difference in national ranking | Cronbach’s alpha reliability | Significance testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative team | 68 | 22 | 46 | 0.910 | t = 16.90, p < 0.01b |

| Overall nursing staff | 74 | 13 | 61 | 0.911 | t = 19.23, p < 0.01b |

| Hospital efficiency | 76 | 23 | 53 | 0.805 | t = 16.89, p < 0.01b |

| Medical records and clinical Information | 49 | 31 | 18 | 0.765 | t = 5.77, p < 0.01b |

| Admission and discharge processes | 72 | 25 | 47 | 0.852 | t = 11.33, p < 0.01b |

| Hospital environment | 73 | 14 | 59 | 0.591 | t = 21.67, p < 0.01b |

| Hospital quality | 74 | 16 | 58 | 0.852 | t = 18.82, p < 0.01b |

| Overall satisfaction | 74 | 16 | 58 | – | t = 21.16, p < 0.01b |

| Overall satisfaction with nurses | 76 | 15 | 61 | – | t = 18.81, p < 0.01b |

| Recommendation | 74 | 17 | 57 | – | t = 19.29, p < 0.01b |

Notes:

n = number of physicians and providers in the HealthStream Physician Engagement Survey database responding from hospitals in the top and bottom quartiles of the culture index.

Differences are statistically significant at the level noted.

Patient experience

For our purposes, we used the HCAHPS survey to measure the patient experience. Hospitals in the cultural index top quartile outperformed the bottom quartile in every single HCAHPS domain with statistical significance (Table 4). The largest areas of positive variance include communication with nurses – 51 percentile points, communication about medicines – 53 percentile points, and overall rating of hospital – 53 percentile points.

Table 4.

Comparisons of culture index top and bottom quartile performers and national ranking performance on HCAHPS

| HCAHPS domains | Top quartile, n = 19,231a | Bottom quartile, n = 39,500a | Difference in national ranking | Cronbach’s alpha reliability | Significance testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication with nurses | 63 | 12 | 51 | 0.780 | z = 7.74, p < 0.01b |

| Communication with doctors | 57 | 16 | 41 | 0.824 | z =14.86, p < 0.01b |

| Responsiveness of hospital staff | 60 | 11 | 49 | 0.687 | z = 4.70, p < 0.01b |

| Cleanliness of the hospital environment | 58 | 13 | 45 | – | z = 9.84, p < 0.01b |

| Quietness of the hospital environment | 46 | 19 | 27 | – | z = 6.99, p < 0.01b |

| Pain management | 68 | 23 | 45 | 0.758 | z = 3.28, p < 0.01b |

| Communication about medicines | 65 | 12 | 53 | 0.625 | z = 0.79, p < 0.01b |

| Discharge information | 72 | 37 | 35 | 0.449 | z = 1.37, p < 0.01b |

| Overall rating of hospital | 70 | 17 | 53 | – | z = 5.96, p < 0.01b |

| Willingness to recommend the hospital | 72 | 26 | 46 | – | z = 7.82, p < 0.01b |

| Transition of care | 75 | 33 | 42 | 0.785 | z = 6.68, p < 0.01b |

Notes:

n = number of patients in the HCAHPS database responding from hospitals in the top and bottom quartiles of the culture index.

Differences are statistically significant at the level noted.

Abbreviation: HCAHPS, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems.

Value-based purchasing

We examined the difference between the culture index top quartile and bottom quartile performers and their facility’s performance across each of the domains that represent VBP. In all but one domain, outcomes, the cultural top quartile exceeded performance of the bottom quartile with statistical significance (Table 5). While the bottom quartile performers for the outcomes score had a higher national ranking by 8 points (top performers: 41st percentile vs bottom performers: 49th percentile) the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 5.

Comparisons of culture index top and bottom quartile performers and national ranking performance on value-based purchasing

| Value-based purchasing domains | Top quartile (n = 81 hospitals)a | Bottom quartile (n = 84 hospitals)a | Difference in national ranking performance | Significance testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient experience of care | 68 | 23 | 45 | t = 9.05, p < 0.01b |

| Clinical process of care | 57 | 41 | 16 | t = 2.03, p < 0.05b |

| Efficiency score | 49 | 24 | 25 | t = 3.58, p < 0.01b |

| Outcomes | 41 | 49 | –8 | t = −1.58, p = 0.118 |

| VBP score | 61 | 29 | 32 | t = 4.83, p < 0.01b |

Notes:

n = number of organizations in the HealthStream Employee Engagement Survey database in the top and bottom quartiles of the culture index.

Differences are statistically significant at the level noted.

Abbreviation: VBP, value-based purchasing.

Additionally, hospitals in the cultural top quartile achieved an average earn-back of 2.4% of their VBP withholding compared with an average of only 1.4% for the bottom quartile. Performance across the top and bottom quartiles equates to being profitable or unprofitable, respectively, with VBP.

Turnover

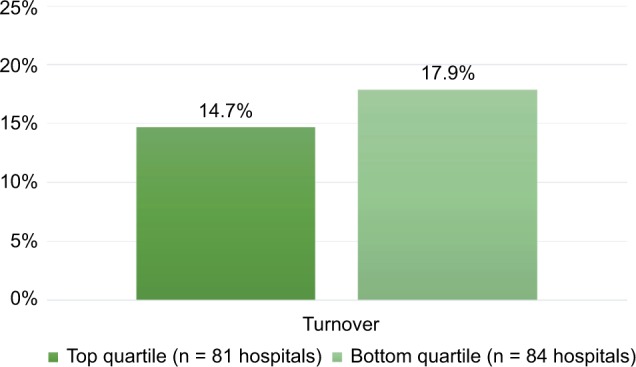

Our research found a 3.2% favorable difference (Figure 1) between the average turnover rates for the cultural top and bottom quartile performers (since lower levels of turnover are more closely linked to positive quality and financial performance). If you are an organization with 4,000 employees, moving from a 17.9% turnover rate to a 14.7% turnover rate could save your organization an average of $2,326,784.32

Figure 1.

Comparisons of culture index top and bottom quartile performers and percentage of self-reported employee turnover.

Recommendations for future study

Our study compares performance across cultural attributes among four nationally representative databases (employee engagement, physician engagement, HCAHPS, and VBP), as well as variance in organizational turnover for these organizations. While HealthStream’s surveys are validated and nationally representative, there may be limited extrapolation to the entire health care workforce due to various ways health systems measure and analyze employee and physician engagement. Since HCAHPS and VBP are nationally comparable “apples to apples” measures, all participating hospitals follow the same standards but the results are focused on the acute care environment. Nevertheless, we do believe leaders should take note of these findings to elevate their focus on leveraging culture to drive outcomes, creating accountability for workforce engagement, and aligning performance standards. As more data become publically available, it will grow our capabilities to assess the impact that culture plays – especially across the continuum of care.

Significance and conclusion

Our team was in a position to establish statistically significant differences in national performance among key indicators of employee engagement, physician/provider engagement, patient experience, VBP, and turnover based on creating top and bottom quartiles for a validated culture index. Our research indicates that attributes of culture can serve as a master lever to steer organizational performance. Cultural attributes representing the degree to which employees believe patients are treated as valued customers, their values are very similar to the values of the organization, being a member of the organization is very rewarding, and they are proud to be a part of this organization are critical to achieving top quartile results across key balanced scorecard metrics. One certainty about health care is its uncertainty – health care will increasingly be a complex and challenging environment. For health care leaders to be successful in the present and future, it is not a matter of “white knuckling” or “holding on tight” through change, they need to harness the power of the people who represent their culture. Culture can seem like an inconvenient truth because it can feel messy, abstract, or difficult to change; however, our findings suggest that leaders should pay close attention to the cultures they are fostering to achieve performance gains. For those who have sought care and been met with employees and providers who have palpable energy, demonstrate compassion, and go above and beyond, those individuals meant the difference between a good or bad experience. Our intent is that these findings will stir a conversation across leadership tables to be intentional about culture. Where hiring and retaining the right individuals, creating clarity of purpose, establishing systems of recognition and performance management, and providing training opportunities to develop the very best workforce are no longer “nice to dos” but performance achievement imperative.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Scott T, Mannion R, Daviews H, Marshall M. Implementing culture change in healthcare: theory and practice. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(2):111–118. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzg021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stubblefield A. The Baptist Health Care Journey to Excellence: Creating a Culture that WOWs. Pensacola: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies H, Nutley S, Mannion R. Organisational culture and quality of health care. Qual Health Care. 2000;9(2):111–119. doi: 10.1136/qhc.9.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Körner M, Wirtz M, Bengel J, Göritz A. Relationship of organizational culture, teamwork and job satisfaction in interprofessional teams. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:243. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0888-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macauley K. Employee engagement: how to motivate your team? J Trauma Nurs. 2015;22(6):298–300. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moghal N. Mission, vision and values statements in healthcare: what are they for? BMJ. 2012;344:e4331. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. nist.gov [webpage on the Internet] How Baldrige Works. 2016. [Accessed January 6, 2017]. Available from: https://www.nist.gov/baldrige/how-baldrige-works.

- 8.DeJong D. Quality improvement using the Baldrige Criteria for Organizational Performance Excellence. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66(11):1031–1034. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boysen P. Just culture: a foundation for balanced accountability and patient safety. Ochsner J. 2013;13(3):400–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trotta A, Cardamone E, Cavallaro G, Mauro M. Applying the balanced scorecard approach in teaching hospitals: a literature review and conceptual framework. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2013;28:181–201. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodak S. 11 Leading Health System CEOs Share Top Goals for 2012. 2011. [Accessed January 3, 2017]. webpage on the Internet. Available from: http://www.becker-shospitalreview.com/hospital-management-administration/11-leading-health-system-ceos-share-top-goals-for-2012.html.

- 12.Owens KM. The HCAHPS Imperative for Patient-Centered Excellence. Pensacola: Baptist Leadership Group; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Medicare.gov [webpage on the Internet] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Compare Hospitals; [Accessed November 20, 2016]. Available from https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/profile.html#profTab=1&ID=100266&cmprID=100266&dist=100&loc=32563&lat=30.3958679&lng=-87.0074423&cmprDist=11.6&Distn=11.6. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Medicare.gov [webpage on the Internet] Datasets. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [Accessed November 20, 2016]. Available from https://data.medicare.gov/data/hospital-compare. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trzeciak S, Gaughan JP, Bosire J, Mazzarelli AJ. Association between medicare summary star ratings for patient experience and clinical outcomes in US hospitals. J Patient Exp. 2016;3(1):6–9. doi: 10.1177/2374373516636681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson MR. Engagement at work: a review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(7):1012–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunetto Y, Xerri M, Shriberg A, et al. The impact of workplace relationships on engagement, well-being, commitment and turnover for nurses in Australia and the USA. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(12):2786–2799. doi: 10.1111/jan.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shuck B, Woolard K. Employee engagement and HRD: a seminal review of the foundations. Human Res Dev Rev. 2010;9(1):89–110. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markos S, Sridevi MS. Employee engagement: the key to improving performance. Int J Bus Manage. 2010;5(12):89–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gelinas LS, Loh DY. The effect of workforce issues on patient safety. Nurs Econ. 2014;22(5):266–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamins C. What Too Many Hospitals Are Overlooking. 2015. [Accessed November 18, 2016]. webpage on the Internet. Available from: http://www.gallup.com/business-journal/181658/hospitals-overlooking.aspx.

- 22.Calayag J. Physician engagement: strengthening the culture of quality and safety. Healthc Exec. 2014;29(2):28–30. 32, 34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henson JW. Reducing physician burnout through engagement. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61(2):86–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiMatteo MR, Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, et al. Physicians characteristics influence patients’ adherence to medical treatments results from medical outcomes study. Health Psychol. 1993;12(2):93–102. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.12.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Latney CR. High reliability organizations: the need for a paradigm shift in healthcare culture. Reflections Nurs Leader. 2016;42(2):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 26. CMS.gov CMS Quality Strategy. [Accessed November 18, 2016]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/Downloads/CMS-Quality-Strategy.pdf.

- 27. CMS.gov [webpage on the Internet] Hospital Value-Based Purchasing. [Accessed November 15, 2016]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/hospital-value-based-purchasing/index.html?redirect=/Hospital-Value-Based-Purchasing/

- 28.Wheeler B. Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 Percentage Payment Summary Report (PPSR) Overview. 2015. [Accessed December 5, 2016]. Available from: http://www.qualityreportingcenter.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/VBP_FY2016_PPSROver-view_NPC_072215_FINAL5081.pdf.

- 29.Collini S, Guidroz A, Perez L. Turnover in health care: the mediating effects of employee engagement. J Nurs Manag. 2015;23(2):169–178. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddy A, Pollack CE. The effect of primary care provider turnover on patient experience of care and ambulatory quality of care. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1157–1162. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. rwjf.org [webpage on the Internet] Princeton: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; [Accessed December 5, 2016]. p. 2009. Available from: http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2009/07/wisdom-at-work-retaining-experienced-nurses/business-case-cost-of-nurse-turnover.html. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waldman JD, Kelly F, Aurora S, Smith HL. The shocking cost of turnover in health care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2014;29(1):2–7. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200401000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]