Abstract

Purpose: To assess the safety and effectiveness of the MDT-2113 (IN.PACT Admiral) drug-coated balloon (DCB) for the treatment of de novo and native artery restenotic lesions in the superficial femoral and proximal popliteal arteries vs percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) with an uncoated balloon in a Japanese cohort. Methods: MDT-2113 SFA Japan (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01947478) is an independently adjudicated, prospective, randomized, single-blinded trial that randomized (2:1) 100 patients (mean age 73.6±7.0 years; 76 men) from 11 Japanese centers to treatment with DCB (n=68) or PTA (n=32). Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups, including mean lesion length (9.15±5.85 and 8.89±6.01 cm for the DCB and PTA groups, respectively). The primary effectiveness outcome was primary patency at 12 months, defined as freedom from clinically-driven target lesion revascularization (CD-TLR) and freedom from restenosis as determined by duplex ultrasonography. The safety endpoint was a composite of 30-day device- and procedure-related death and target limb major amputation and clinically-driven target vessel revascularization within 12 months. Results: Patients treated with DCBs exhibited superior 12-month primary patency (89%) compared to patients treated with PTA (48%, p<0.001). The 12-month CD-TLR rate was 3% for DCB vs 19% for PTA (p=0.012). There were no device- or procedure-related deaths, major amputations, or thromboses in either group. Quality-of-life measures showed sustained improvement from baseline to 12 months in both groups. Conclusion: Results from the MDT-2113 SFA Japan trial showed superior treatment effect for DCB vs PTA, with excellent patency and low CD-TLR rates. These results are consistent with other IN.PACT SFA DCB trials and demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of this DCB for the treatment of femoropopliteal lesions in this Japanese cohort.

Keywords: angioplasty, claudication, drug-coated balloon, femoropopliteal segment, paclitaxel, peripheral artery disease, popliteal artery, randomized controlled trial, superficial femoral artery

Introduction

Treatment guidelines for femoropopliteal lesions have been updated significantly in the past decade because of improved outcomes associated with the use of novel endovascular devices, particularly nitinol stents. Self-expanding nitinol stents have shown superior efficacy over standard percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) in the superficial femoral artery (SFA) and/or proximal popliteal artery (PPA).1–4 Randomized trials have demonstrated superiority of primary stenting with bare nitinol stents over PTA, with 1-year patency rates ranging from 63% to 81%.1–3 Similarly, advances in drug elution technology have proven that drug-eluting stents (DES) are better than PTA in this challenging vessel segment.4 Positive results have been reported with DES in a large cohort of Japanese patients.5

Despite the sustained benefits of stents, therapeutic success has been shown to correlate with underlying disease and lesion complexity, including lesion length, chronic total occlusions, and calcification.6,7 Moreover, even with newer stent designs concerns still remain regarding how best to treat in-stent restenosis and late stent-related adverse events, including stent fracture.8–10 Given these challenges, an effective “leave nothing behind” treatment strategy that circumvents the use of metallic implants while preserving future therapeutic options is attractive.

In recent years, the use of drug-coated balloons (DCB) in femoropopliteal lesions has become widespread. To date, randomized clinical trials have demonstrated superior patency with DCBs compared to PTA11–16; however, these studies were limited to patients with short and intermediate lesions defined as TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus (TASC) A or B lesions, for which guidelines recommend an endovascular approach as first-line therapy.17 Initial results from single-center experiences and small randomized trials demonstrating a reduction in restenosis rates and the need for reinterventions with DCBs compared with standard PTA12,18–20 have paved the way for larger randomized studies. The IN.PACT SFA trial reported superior primary patency and a reduction in CD-TLR with DCB vs PTA at 12 months11 and more recently demonstrated sustained benefit with the DCB at 24 months.21

The evidence base showing positive treatment outcomes with DCB is founded almost exclusively on Caucasian patients in European and American populations. Pathophysiological differences in the presentation of PAD have been reported between ethnic groups,22,23 which may adversely impact response to treatment. A recent subanalysis of the Zilver PTX registry reported no ethnic differences in the performance of DES in Japanese patients.24 In the present trial, the efficacy and safety of the MDT-2113 DCB vs conventional PTA in patients with TASC A, B, and C lesions was evaluated in a Japanese population.

Methods

Study Design

MDT-2113 SFA Japan is a prospective, multicenter, randomized, single-blinded, phase III trial aimed at evaluating the safety and efficacy of the MDT-2113 device (IN.PACT Admiral; Medtronic, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) compared with standard PTA in Japanese patients with symptomatic de novo or native vessel restenotic lesions in the SFA/PPA. The trial was designed to be part of a series including IN.PACT SFA I (conducted in Europe) and IN.PACT SFA II (conducted in the United States), collectively known as the IN.PACT SFA trial. Although not independently powered, the MDT-2113 SFA Japan trial, with a planned enrollment of 100 subjects and a design identical to the IN.PACT SFA trial,11,21 was intended to demonstrate consistent effectiveness and safety outcomes for a Japanese cohort compared to other measured geographies in the IN.PACT SFA trial. The MDT-2113 SFA Japan trial was registered on the National Institutes of Health website (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01947478).

The trial included independent oversight by a Data Safety Monitoring Board and Clinical Events Committee (CEC), which reviewed and adjudicated all major adverse events through 12 months postintervention. Independent ultrasound (VasCore; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA) and angiography (SynvaCor, Springfield, IL, USA) core laboratories analyzed procedure and follow-up images. The independent core laboratories and CEC were blinded and remain blinded to the treatment assignments through the 36-month follow-up duration. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, good clinical practice guidelines, and applicable laws as specified by all relevant government authorities. Prior to enrollment, written informed consent was obtained from all patients according to the protocols approved by the institutional review boards at each of the 11 investigational sites.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Patients between the ages of 20 and 85 years with symptoms of claudication and/or ischemic rest pain (Rutherford category 2–4) were eligible for inclusion in the trial if they had a 70% to 99% stenosis measuring between 4 and 20 cm or occlusions ≤10 cm long in the SFA and/or PPA. The lesions ranged in complexity from TASC A to C.

Patient Enrollment and Randomization

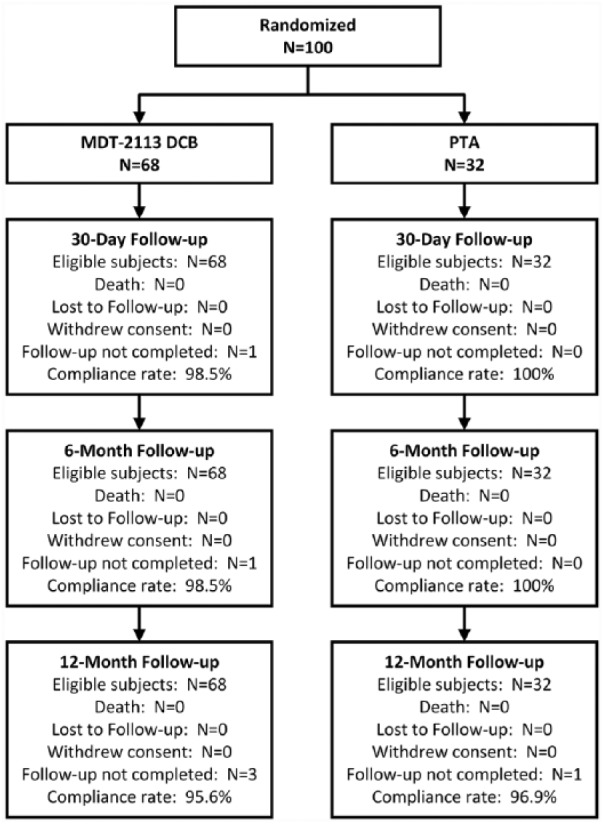

One hundred patients (mean age 73.6±7.0; 76 men) were enrolled at 11 centers in Japan. Patient flow through the 12-month follow-up is described in Figure 1. Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to treatment with DCB (n=68) or PTA (n=32) during the procedure providing all eligibility criteria were met, including successful predilation.

Figure 1.

One hundred patients enrolled in the MDT-2113 SFA Japan trial were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to treatment with DCB or standard PTA. Deaths, lost to follow-up, visits not completed, and withdrawals through 1 year are shown. DCB, drug-coated balloon; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty.

Study Device

Patients randomized to the test arm were treated with the single-inflation MDT-2113 DCB (IN.PACT Admiral), which is coated with paclitaxel, an antiproliferative agent, at a dose of 3.5 µg/mm2 in a urea excipient. Multiple balloon diameters (4, 5, 6, and 7 mm) and lengths (20, 40, 60, 80, and 120 mm) were available in the study (the 7-mm diameter device was not available in the 120-mm length). To avoid geographic miss, DCB length was chosen to exceed the target lesion length by 10 mm at the proximal and distal edges. If treatment required multiple balloons, a 10-mm overlap was applied for contiguous balloon inflations.

Treatment and Medical Therapy

Premedication included aspirin (minimum of 81 mg daily for at least 5 consecutive days prior to the procedure) and clopidogrel (according to the manufacturer’s instructions for use). Heparin was administered at the time of the procedure to maintain an activated clotting time of 250 seconds. A minimum balloon inflation time of 180 seconds was required for both the test and control (uncoated balloon) groups. Postdilation with a standard PTA balloon was allowed at the discretion of the operator. In both treatment groups, provisional stenting was allowed only in case of residual stenosis ≥50% or major (≥grade D) flow-limiting dissection confirmed by a peak translesion gradient >10 mm Hg despite repeated and prolonged PTA inflations.

In both arms, postprocedure medical therapy included aspirin (minimum 81 mg/d for a minimum of 6 months) and clopidogrel daily for a minimum of 1 month for nonstented patients and 3 months for patients who received stents.

Follow-up

For primary endpoint reporting, patients were followed by the treating physician at 30 days, 6 months, and 12 months, including office visits with duplex ultrasound, functional testing, and adverse event assessment. Reinterventions, if required within 12 months of the procedure, were performed according to standard practice using PTA balloons and provisional stenting.

Study Outcome Measures

The primary efficacy outcome was primary patency at 12 months following the index procedure, defined as freedom from clinically-driven target lesion revascularization (CD-TLR) and freedom from restenosis as determined by duplex-derived peak systolic velocity ratio (PSVR) ≤2.4.25 Each component of the endpoint was independently adjudicated by the blinded CEC (for CD-TLR) or by the core laboratories (for restenosis). CD-TLR was defined as reintervention at the target lesion due to symptoms or decrease in ankle-brachial index (ABI) ≥20% or >0.15 compared with the postprocedure ABI. The primary safety outcome was a composite of freedom from 30-day device- and procedure-related death and freedom from target limb major amputation and clinically-driven target vessel revascularization (CD-TVR) through 12 months.

The secondary endpoints included major adverse events (MAEs) defined as death from any cause, CD-TVR, major target limb amputation, and thrombosis at the target lesion site at 12 months. Thrombosis was defined as a rapidly evolving total thrombotic occlusion with sudden onset of symptoms and documented by duplex and/or angiography.

Additional assessments at 12 months included individual components of the MAE composite endpoint; binary restenosis (PSVR >2.4) of the target lesion; sustained primary clinical improvement (defined as no target limb amputation or TVR and an improvement shift of 1 Rutherford category at 12 months); device success; procedure success; and clinical success. Functional assessments included general appraisal through administration of the EuroQOL (EQ-5D), a 5-dimension generic health status questionnaire,26 a 6-minute walking test,27 and specific evaluation of walking capacity using the Walking Impairment Questionnaire (WIQ).28 Additionally, data on intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) usage were analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were based on the intent-to-treat principle. For baseline characteristics, continuous variables were described as mean ± standard deviation and were compared using t tests; dichotomous and categorical variables were described as counts and proportions and were compared with the Fisher exact test or Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, respectively. A 2-sample Z-test was used to compare 12-month primary patency between the 2 groups. In addition, the Kaplan-Meier method was used to evaluate time-to-event data for primary patency and CD-TLR over the 12-month follow-up period. The difference in the survival curves between groups was assessed using the log-rank test. For all endpoints, the level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05 with no correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline and Procedure Characteristics

The treatment groups were well matched at baseline with similar demographics, comorbidities, and lesion characteristics (Tables 1 and 2). The mean lesion length was 9.15±5.85 cm in the DCB group vs 8.89±6.01 cm in the PTA group (p=0.838); 11 (16%) of 68 DCB-treated lesions and 5 (16%) of 32 PTA-treated lesions were occlusions. Percent diameter stenosis was 80.2%±14.1% and 80.7%±12.5% (p=0.861) for DCB and PTA, respectively. The provisional stent rate was low and similar between groups (4% DCB vs 3% PTA, p=0.759). During the index procedure, IVUS was used in 27 (40%) DCB cases and 28 (5%) PTA patients to optimize vessel size (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient and Lesion Characteristics.a

| Characteristics | DCB (n=68) | PTA (n=32) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 73.3±7.4 | 74.2±6.1 | 0.539 |

| Men | 50/68 (74) | 26/32 (81) | 0.461 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m²) | 3/68 (4) | 0/32 (0) | 0.549 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40/68 (59) | 18/32 (56) | 0.831 |

| Insulin dependent | 10/68 (15) | 6/32 (19) | 0.771 |

| Current smoker | 18/68 (26) | 10/32 (31) | 0.639 |

| Carotid artery disease | 12/65 (18) | 5/31 (16) | >0.999 |

| Coronary heart disease | 34/68 (50) | 16/32 (50) | >0.999 |

| Renal Insufficiency | 6/68 (9) | 4/32 (13) | 0.722 |

| Previous peripheral revascularization | 39/68 (57) | 19/32 (59) | >0.999 |

| BTK involvement | 23/68 (34) | 11/32 (34) | >0.999 |

| Previous limb amputation | 1/68 (1) | 0/32 (0) | >0.999 |

| ABI/TBI | 0.76±0.15 | 0.74±0.17 | 0.384 |

| Rutherford category | |||

| 2 | 37/68 (54) | 19/32 (59) | 0.623 |

| 3 | 28/68 (41) | 12/32 (38) | |

| 4 | 3/68 (4) | 1/32 (3) | |

| Angiographic characteristics | |||

| De novob | 62/68 (91) | 32/32 (100) | 0.085 |

| Restenotic (nonstented)b | 6/68 (9) | 0/32 (0) | |

| Proximal popliteal involvementc | 1/68 (1) | 1/32 (3) | 0.540 |

| Severe calcificationc | 5/68 (7) | 3/32 (9) | 0.708 |

| Lesion length, cmc,d | 9.15±5.85 | 8.89±6.01 | 0.838 |

| Total occlusionsc | 11/68 (16) | 5/32 (16) | >0.999 |

| TASC II classificationc | 0.852 | ||

| A | 39/68 (57) | 18/32 (56) | |

| B | 16/68 (23) | 7/32 (22) | |

| C | 13/68 (19) | 7/32 (22) | |

| RVD, mmc | 4.84±0.75 | 4.68±0.66 | 0.280 |

| MLD, mmc | 0.97±0.73 | 0.90±0.59 | 0.610 |

| Diameter stenosis, %c | 80.2±14.1 | 80.7±12.5 | 0.861 |

Abbreviations: ABI, ankle-brachial index; BMI, body mass index; DCB, drug-coated balloon; MLD: mean lesion diameter; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; RVD, reference vessel diameter; TASC, TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus II; TBI, toe-brachial index.

Continuous data are presented as the means ± standard deviation; categorical data are given as the count/sample (percentage).

Site-reported.

Per lesion assessment reported by the core laboratory.

Normal-to-normal by core laboratory quantitative vascular analysis.

Table 2.

Procedure Characteristics.a

| Characteristics | DCB (n=68) | PTA (n=32) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predilationb | 68/68 (100) | 32/32 (100) | >0.999 |

| Postdilationb | 16/68 (24) | 6/32 (19) | 0.796 |

| Provisional stentingb | 3/68 (4) | 1/32 (3) | 0.759 |

| Index procedure IVUS use | 27/68 (40) | 8/32 (25) | 0.181 |

| DCBs per subjectb | 1.4±0.5 | 1.1±0.2 | <0.001 |

| Dissection | |||

| None | 18/68 (26) | 9/32 (28) | 0.235 |

| A-C | 50/68 (74) | 23/32 (72) | |

| D-F | 0/68 (0) | 0/32 (0) | |

| Hospitalization, db | 2.0±1.0 | 2.1±1.2 | 0.778 |

| Lesion length treated, cmc | 13.4±5.1 | 13.7±5.6 | 0.800 |

| Device success | 97/97 (100) | 33/34 (97) | 0.260 |

| Procedure success | 66/68 (97) | 32/32 (100) | >0.999 |

| Clinical success | 66/68 (97) | 32/32 (100) | >0.999 |

Abbreviations: DCB, drug-coated balloon; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty.

Continuous data are presented as the means ± standard deviation; categorical data are given as the count/sample (percentage).

Site-reported.

Per lesion assessment reported by the core laboratory.

Efficacy Outcomes

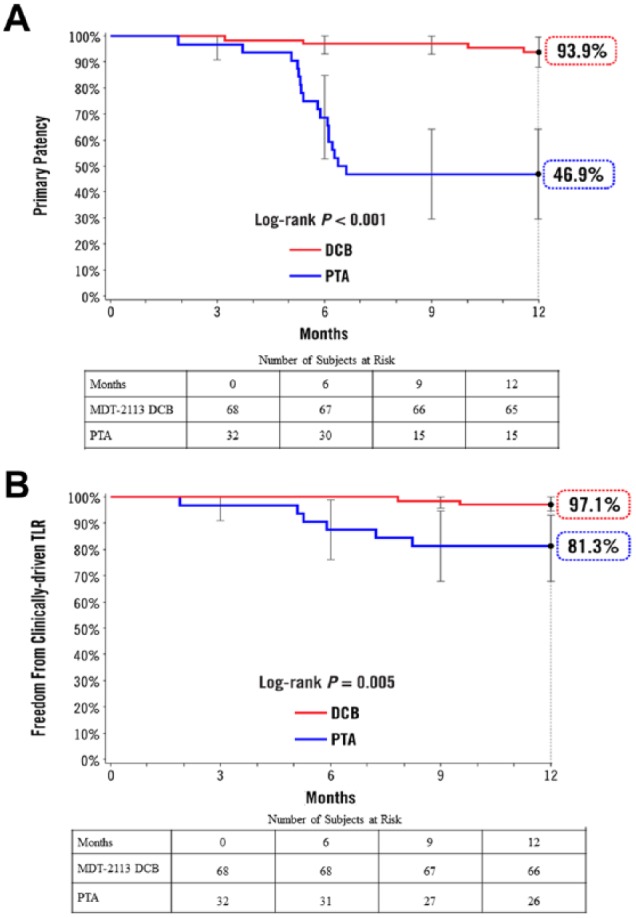

Procedure success, defined as residual diameter stenosis ≤50% for nonstented patients or ≤30% for stented patients, was achieved in 97% of subjects in the DCB group and 100% of patients in the PTA group (p>0.99). The primary patency rate at 12 months was significantly higher with DCB than PTA (89% vs 48%, p<0.001; Table 3). The Kaplan-Meier estimate of primary patency was 93.9% for DCB compared to 46.9% for PTA (p<0.001; Figure 2A). An ad hoc evaluation of patency by IVUS use during the index procedure showed that in patients whose vessels were viewed by IVUS outperformed non-IVUS studied counterparts. In the DCB group, patency was 96% for IVUS use vs 85% for no-IVUS use, while in the PTA group, patency was 71% vs 42% for IVUS vs no-IVUS use, respectively.

Table 3.

Key Efficacy and Safety Outcomes at 12 Months.

| Outcome | DCBa | PTAa | Difference, %b | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary patencyc | 58/65 (89) | 15/31 (48) | 38 [19, 57] | <0.001 |

| By IVUS use during index procedure | — | — | ||

| Yes | 25/26 (96) | 5/7 (71) | — | — |

| No | 33/39 (85) | 10/24 (42) | — | — |

| 12-Month efficacy outcomes | ||||

| Binary restenosisd | 6/64 (9) | 10/25 (40) | — | 0.002 |

| All TLRe | 2/68 (3) | 6/32 (19) | −16 [−32, −4] | 0.012 |

| CD-TLRf | 2/68 (3) | 6/32 (19) | — | 0.012 |

| By IVUS use during index procedure | ||||

| Yes | 1/27 (4) | 1/8 (13) | ||

| No | 1/41 (2) | 5/24 (21) | ||

| CD-TVR | 3/68 (4) | 6/32 (19) | — | 0.028 |

| By IVUS use during index procedure | ||||

| Yes | 1/27 (4) | 1/8 (13) | ||

| No | 2/41 (5) | 5/24 (21) | ||

| Sustained primary clinical improvementg | 61/65 (94) | 22/31 (71) | — | 0.004 |

| By IVUS use during index procedure | ||||

| Yes | 25/26 (96) | 6/7 (86) | ||

| No | 36/39 (92) | 16/24 (67) | ||

| ABI/TBI | 0.93±0.12 (68) | 0.92±0.14 (32) | — | 0.722 |

| 12-month safety outcomes | ||||

| Primary safety compositeh | 65/68 (96) | 26/32 (81) | 14 [2, 31] | 0.028 |

| 30-day device- and procedure-related death | 0/68 (0) | 0/32 (0) | — | |

| Target limb major amputation | 0/68 (0) | 0/32 (0) | — | |

| All-cause death | 0/68 (0) | 0/32 (0) | — | |

| Thrombosis | 0/68 (0) | 0/32 (0) | — | |

Abbreviations: ABI, ankle-brachial index; CD-TLR, clinically-driven target lesion revascularization; CD-TVR, clinically-driven target vessel revascularization; DCB, drug-coated balloon; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; TBI, toe-brachial index; TLR, target lesion revascularization; TVR, target vessel revascularization.

Continuous data are presented as the means ± standard deviation (sample); categorical data are given as the count/sample (percentage).

Difference is presented with the 95% confidence interval in brackets.

Defined as freedom from CD-TLR and freedom from restenosis as determined by duplex ultrasound peak systolic velocity ratio (PSVR) ≤2.4.

Defined as duplex restenosis (PSVR >2.4) of the target lesion at 12 months or at the time of reintervention.

Includes clinically-driven and incidental or duplex-driven TLR.

Defined as any reintervention within the target vessel due to symptoms or drop in ABI/TBI ≥20% or >0.15 compared with postprocedure ABI/TBI.

Defined as no target limb amputation or TVR and an increase in Rutherford class at 12 months postprocedure.

Defined as no 30-day device- and procedure-related death, target limb major amputation, or CD-TVR through 12 months.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of (A) primary patency and (B) clinically-driven target lesion revascularization (TLR) at 12 months. Bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. DCB, drug-coated balloon; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty Number at risk represents the number of evaluable subjects at the beginning of the 30-day window prior to each follow-up interval.

DCB-treated patients demonstrated significantly lower CD-TLR rates at 12 months (3% vs 19%, p=0.012) compared with patients treated with PTA (Figure 2B, Table 3). Significantly higher sustained primary clinical improvement was observed in the DCB group compared with PTA (94% vs 71%, p=0.004).

Safety Outcomes

Safety outcomes through 12 months are reported in Table 3. The primary safety composite endpoint of freedom from 30-day device- and procedure-related death and 12-month target limb major amputation and CD-TVR was 96% in the DCB group vs 81% in the PTA group (p=0.028). There were no procedure- or device-related deaths, major amputations, thromboses, or all cause deaths through 12 months in either group.

Functional Outcomes

At 12 months, both treatment groups showed similar improvement from baseline in all functional outcomes assessed, including the quality of life assessment by EQ-5D index, WIQ, and 6-minute walk test. The mean change in the EQ-5D index from baseline to 12 months was 0.081±0.149 for DCB vs 0.095±0.157 for PTA (p=0.705). Using the 6-minute walk test, the distance traveled at baseline was similar between groups (350.4±97 m for DCB vs 354.5±71.9 m for PTA; p=0.825). At 12 months, both groups showed similar improvement in walking distance (23.7±37.8 m DCB vs 8.8±29.8 m PTA; p=0.156). Despite improvement in functional outcomes in both groups, patients treated with DCB required 77% fewer reinterventions than their PTA-treated counterparts.

Discussion

Several randomized trials have shown superior benefit with DCB over PTA in patients with femoropopliteal disease.12,14–16,18–20 These reports indicate higher patency rates for DCB in comparison with uncoated balloons. Although these studies provide valuable insights into the benefits of DCB, the patients studied have been exclusively Caucasian, European, and American populations. To date, this is the first randomized trial evaluating DCB in a specific cohort of Japanese patients undergoing treatment for symptomatic femoropopliteal disease.

Japanese patients in the phase III MDT-2113 SFA Japan trial had significantly greater primary patency and fewer reinterventions of the target lesion at 12 months compared to those treated with an uncoated balloon. In terms of safety outcomes, no difference was observed between the groups in the incidence of death, limb amputation, or transition to surgical treatment within 30 days or at 12 months. The MDT-2113 SFA Japan trial was modeled after the randomized IN.PACT SFA trial in terms of design, DCB device evaluated, and outcomes assessed. At 12 months, Kaplan-Meier estimates in the IN.PACT SFA trial11,21 were 87.5% for patency rate and 2.4% for CD-TLR, which were quite similar to the 89% and 3% rates, respectively, from the present study.

There were important differences between the MDT-2113 SFA Japan cohort and patient groups from other similarly conducted studies. Japanese patients were on average older at the time of the procedure. The average age was 74 years in this cohort vs ~68 years in the IN.PACT SFA11 and LEVANT II13 randomized trials but identical (73.5 years) to the Japanese study population in the Zilver PTX registry.5 The proportion of patients with diabetes was also higher [59% (DCB) and 56% (PTA)] in comparison with the 40% to 49% enrolled in other studies.11,13 The present trial planned to enroll patients with lesions of up to 20 cm in length. The 9-cm mean lesion length for the DCB arm was similar to lengths in the IN.PACT SFA DCB group (9 cm) but longer than lesions in the LEVANT II (6 cm) and Zilver PTX DES (7 cm)4 trials. Despite longer lesions and a sicker patient population in this study, outcomes were still favorable for DCB, while those treated with PTA were relatively poor.

In our trial, the provisional stent rate was very low despite the presence of longer lesions. Possible explanations for this low rate include optimal PTA technique, the use of IVUS, and exclusion of severe calcification per the study protocol, which likely limited the occurrence of severe dissections that may require stent use. In general, procedures for achieving optimal PTA at medical centers have changed in recent years. For one, the use of prolonged balloon inflations may have contributed to the low provisional stent rate we observed. Also, in recent years, IVUS has been incorporated in many institutions in Japan for endovascular procedures. IVUS was not mandated by the study protocol; its use was at the discretion of the implanting physician and per institutional practice. In the present study IVUS was used in 40% of DCB vs 25% of PTA patients, which allowed detailed assessment of vessel diameter and morphology, possibly leading to treatment without an excessive pressure load. Importantly, there was a trend toward improved outcomes in patients whose vessels were evaluated with IVUS before the procedure. Despite smaller numbers, there were marked differences in the PTA group with 12-month patency rates of 71% vs 42% for IVUS use vs no IVUS use, respectively. Additional studies are needed to provide insights regarding this observation.

While the MDT-2113 DCB was shown to be superior to PTA in this trial, it is important to note that these results may not be generalizable to other DCBs. Each DCB is unique in terms of the paclitaxel dose (2.0–3.5 µg/mm2) on the balloon, the excipient, and the coating process employed to get the drug on the balloon. Each feature has the potential to influence the dose of paclitaxel delivered to the vessel wall and thus the effectiveness of the treatment. Each technology must be evaluated critically and stand on its own merit.

Limitations

Although this randomized controlled trial was rigorously conducted with blinding and extensive oversight by core laboratories and a CEC, it enrolled only a limited number of patients. However, statistically significant superiority of DCB treatment effect was demonstrated in this small sample size, positively reinforcing the impact of DCBs.

The study is restricted to Japanese patients and thus is not generalizable to other patient populations. That said, outcomes were consistent with those reported in other studies, which could demonstrate that the therapeutic effect of DCBs is not affected by racial differences.

Conclusion

Results from the MDT-2113 SFA Japan trial showed superior treatment effect with DCB vs PTA, with remarkably high patency and low CD-TLR rates. These results are consistent with other IN.PACT SFA DCB trials and demonstrate the safety and efficacy of this DCB for the treatment of complex femoropopliteal lesions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients for their participation in this clinical study. The authors also recognize the principal investigators (in parentheses) and institutions in Japan that enrolled patients in the study: Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, Kamakura (Shigeru Saito, MD); Toho University Medical Center, Ohashi Hospital, Tokyo (Masato Nakamura, MD); Yokohama Tobu Hospital, Yokohama (Keisuke Hirano, MD); Kansai Rosai Hospital, Amagasaki (Osamu Iida, MD); Tokeidai Memorial Hospital, Sapporo (Kazushi Urasawa, MD); Sendai Kousei Hospital, Sendai (Naoto Inoue, MD); Kasukabe Chuo General Hospital, Kasukabe (Hiroshi Ando, MD); Kikuna Memorial Hospital, Yokohama (Junko Hone, MD); and Omihachiman Community Medical Center, Omihachiman (Takuo Nakagami, MD). The authors thank Azah Tabah, PhD, for medical writing assistance.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This study was presented in various forms at LINC 2017 (Leipzig, Germany; January 24–27, 2017); JET 2017 (Shinagawa, Japan; February 17–19, 2017); and CRT 2017 (Washington, DC; February 18–21, 2017).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Hong Wang and Hiroko Ookubo are full-time employees of Medtronic. Michael R. Jaff is a noncompensated advisor for Medtronic, an equity investor in PQ Bypass, and a compensated board member of VIVA Physicians, a 501c3 not-for-profit education and research organization.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by Medtronic plc.

ORCID iD: Osamu Iida  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5424-3946

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5424-3946

References

- 1. Schillinger M, Sabeti S, Loewe C, et al. Balloon angioplasty versus implantation of nitinol stents in the superficial femoral artery. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1879–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dick P, Wallner H, Sabeti S, et al. Balloon angioplasty versus stenting with nitinol stents in intermediate length superficial femoral artery lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;74:1090–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laird JR, Katzen BT, Scheinert D, et al. Nitinol stent implantation vs. balloon angioplasty for lesions in the superficial femoral and proximal popliteal arteries of patients with claudication: three-year follow-up from the RESILIENT randomized trial. J Endovasc Ther. 2012;19:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dake MD, Ansel GM, Jaff MR, et al. Paclitaxel-eluting stents show superiority to balloon angioplasty and bare metal stents in femoropopliteal disease: twelve-month Zilver PTX randomized study results. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:495–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yokoi H, Ohki T, Kichikawa K, et al. Zilver PTX post-market surveillance study of paclitaxel-eluting stents for treating femoropopliteal artery disease in Japan: 12-month results. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Soga Y, Iida O, Hirano K, et al. Mid-term clinical outcome and predictors of vessel patency after femoropopliteal stenting with self-expandable nitinol stent. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rocha-Singh KJ, Bosiers M, Schultz G, et al. for the DURABILITY II Investigators. A single stent strategy in patients with lifestyle limiting claudication: 3-year results from the DURABILITY II trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;86:164–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scheinert D, Scheinert S, Sax J, et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of stent fractures after femoropopliteal stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:312–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schlager O, Dick P, Sabeti S, et al. Long-segment SFA stenting–the dark sides: in-stent restenosis, clinical deterioration, and stent fractures. J Endovasc Ther. 2005;12:676–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Laird JR, Yeo KK. The treatment of femoropopliteal in-stent restenosis: back to the future. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:24–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tepe G, Laird J, Schneider P, et al. ; IN.PACT SFA Trial Investigators. Drug-coated balloon versus standard percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for the treatment of superficial femoral and popliteal peripheral artery disease: 12-month results from the IN.PACT SFA randomized trial. Circulation. 2015;131:495–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scheinert D, Duda S, Zeller T, et al. The LEVANT I (Lutonix paclitaxel-coated balloon for the prevention of femoropopliteal restenosis) trial for femoropopliteal revascularization: first-in-human randomized trial of low-dose drug-coated balloon versus uncoated balloon angioplasty. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosenfield K, Jaff MR, White CJ, et al. ; LEVANT 2 Investigators. Trial of a paclitaxel-coated balloon for femoropopliteal artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scheinert D, Schulte KL, Zeller T, et al. Paclitaxel-releasing balloon in femoropopliteal lesions using a BTHC excipient: twelve-month results from the BIOLUX P-I randomized trial. J Endovasc Ther. 2015;22:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krishnan P, Faries P, Niazi K, et al. Stellarex drug-coated balloon for treatment of femoropopliteal disease: twelve-month outcomes from the randomized ILLUMENATE pivotal and pharmacokinetic studies. Circulation. 2017;136: 1102–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schroeder H, Werner M, Meyer DR, et al. ; ILLUMENATE EU RCT Investigators. Low-dose paclitaxel-coated versus uncoated percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty for femoropopliteal peripheral artery disease: one-year results of the ILLUMENATE European randomized clinical trial (Randomized Trial of a Novel Paclitaxel-Coated Percutaneous Angioplasty Balloon). Circulation. 2017;135:2227–2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. TASC Steering Committee, Jaff MR, White CJ, et al. An update on methods for revascularization and expansion of the TASC lesion classification to include below-the-knee arteries: a supplement to the Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). J Endovasc Ther. 2015;22:663–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tepe G, Zeller T, Albrecht T, et al. Local delivery of paclitaxel to inhibit restenosis during angioplasty of the leg. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:689–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Werk M, Langner S, Reinkensmeier B, et al. Inhibition of restenosis in femoropopliteal arteries: Paclitaxel-coated versus uncoated balloon: femoral paclitaxel randomized pilot trial. Circulation. 2008;118:1358–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Werk M, Albrecht T, Meyer DR, et al. Paclitaxel-coated balloons reduce restenosis after femoro-popliteal angioplasty: evidence from the randomized PACIFIER trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:831–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laird JR, Schneider PA, Tepe G, et al. ; IN.PACT SFA Investigators. Durability of treatment effect using a drug-coated balloon for femoropopliteal lesions: 24-month results of IN.PACT SFA. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2329–2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hobbs SD, Wilmink AB, Bradbury AW. Ethnicity and peripheral arterial disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003;25:505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bennett PC, Silverman S, Gill PS, et al. Ethnicity and peripheral artery disease. QJM. 2009;102:3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ohki T, Yokoi H, Kichikawa K, et al. Two-year analysis of the Japanese cohort from the Zilver PTX randomized controlled trial supports the validity of multinational clinical trials. J Endovasc Ther. 2014;21:644–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schlager O, Francesconi M, Haumer M, et al. Duplex sonography versus angiography for assessment of femoropopliteal arterial disease in a “real-world” setting. J Endovasc Ther. 2007;14:452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chetter IC, Spark JI, Dolan P, et al. Quality of life analysis in patients with lower limb ischaemia: suggestions for European standardisation. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1997;13:597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McDermott MM, Ades PA, Dyer A, et al. Corridor-based functional performance measures correlate better with physical activity during daily life than treadmill measures in persons with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:1231–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Regensteiner JG, Panzer RJ, Hiatt WR. Evaluation of walking impairment by questionnaire in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Med Biol. 1990;2:142–152. [Google Scholar]