Introduction

The Institute of Medicine and Food and Drug Administration recognize that activating clinical trials in the United States is lengthy and inefficient. Downstream consequences include increased expense, suboptimal accrual, move of clinical trials overseas and delayed availability of treatments for patients. An in-tandem processing initiative is here highlighted that transformed the activation of clinical trials (TACT), reduced the activation time by 70%, and offers a paradigm for enhanced translational readiness.

Transforming the Process

National academies and regulatory agencies have identified a major need in expediting the launch of clinical trials to ensure an optimized, competitive and cost-effective translational process.(1, 2) A plan-do-study-act (PDSA) process (3), Design for Six Sigma, and Lean 3P methodologies were used to redesign the entire process (Table 1), which was tested in selected pilot trials, then implemented institution-wide (final phase) at Mayo Clinic sites in Rochester, Minnesota; Jacksonville, Florida; and Scottsdale, Arizona. The project was limited to industry-funded trials, where process flows, activation timelines, and funding are more predictable than federally-sponsored trials.

Table 1.

Comprehensive Changes to Ingredients of Activating Clinical Trials

| No. | Subproject | Previous State | Current State |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Process transformation | Sequential process with lag time between process steps, rework needed and no central coordination | Parallel process with emphasis on first-time quality and central coordination Overall process changes

|

| 2 | Contract signature | Sequential process between IRB approval and contract signature results in delayed activation timeline |

|

| 3 | Budgets and coding solutions | Complex procedure code identification process | Simplified process of identifying procedure codes Reduction in duration of budget negotiation timeline Code and coverage analysis

|

| 4 | Facilitation | Clinical trial activation managed by individual study teams | Central coordination of clinical trial activation Facilitator coordinated the process, with emphasis on open communication, timeline expectations, and accountability |

| 5 | Prioritization | No prioritization criteria established |

|

| 6 | IT coding solutions | Electronic system enhancements to support outcomes of other subprojects

|

Abbreviations: ACTA, accelerated clinical trial agreements; CCA, code and coverage analysis; IRB, institutional review board; IT, information technology; LCA, Legal Contract Administration; OSPA, Office of Sponsored Projects Administration.

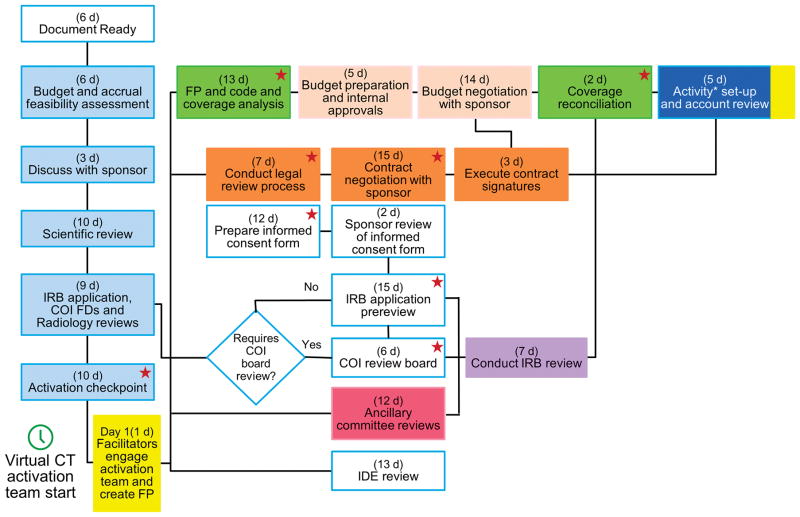

The fundamental change was a process in which the financial, contractual and regulatory steps occur in parallel rather than in series (Figure 1). Other changes were the creation of integrated work teams, less complexity, improved quality, more effective communication among business units, and the elimination of redundant work, barriers, and waste while ensuring that protection of research participants remained the leading priority. Every trial had a facilitator, i.e. a project manager, who ensured, at the outset, that the sponsor and study teams were committed to the process and timeline. Most studies (ACT1 studies, 38 of 40 pilot and 71 of 105 final trials) adhered to a 65 day timeline. For the remaining (ACT2) studies, the actual timeline was negotiated on a case-by-case basis with study sponsors. Extensive face-to-face training and new electronic tools were provided to all participants. For all trials, the total time for all steps from submission of the funding proposal to account creation was measured in calendar days. During the pilot phase, the actual work time was also measured.

Figure 1.

Transformed Process Flow for Transforming the Activation of Clinical Trials at a Single Site. In each box, the exhibits represent maximum duration (business days) assigned to each process step. This exhibit represents the flow for part 1 studies. For part 2 studies, the design was modified slightly on the basis of the plan-do-study-act process. All activities affecting the consent form are designated with the star icon. Asterisk indicates 39 business days from creation of FP to financial activation. The colors corresponds to colors for corresponding steps in Supplementary Table 1. COI indicates conflict of interest; CT, clinical trial; FD, financial disclosure; FP, funding proposal; IDE, Investigational Device Exemption; IRB, institutional review board.

Expedited Outcomes

Before TACT, the median (IQR) activation times were 189 (134–264) calendar days in 2013 (277 trials), 166 (126–251) days in 2014 (296 trials), and 168 (123–244) days in 2015 (333 trials). By comparison, 109 ACT1 trials were activated in 59 [43–63] days, P<.001). Of these 109 trials, 91 were drug trials, 17 included a device, and 1 evaluated a behavioral intervention. Among drug studies, 17 were phase 1, 10 were phase 1–2, 34 were phase 2, 1 was phase 2–3, 24 were phase 3, and 5 were phase 4 studies. The 34 ACT2 studies were activated in 63 (49–95) days. It took longer (P=.002) for studies to be activated at 2 or 3 Mayo Clinic sites than at 1 site. During the pilot phase, actual work time for individual steps was considerably shorter than time required to process these steps (Supplementary Table 1).

Lessons Learned and Relevance to Implementing TACT

Through a transformed and unique process that works in parallel (rather than in series), the time required to activate clinical trials was reduced by 70% at 3 geographically diverse and distant Mayo Clinic sites. Because the actual work time was a fraction of the total time taken for individual steps, the gains from TACT were achieved primarily by reducing the non–value-added time (i.e., wait or rework time) between steps (4), reducing rework, and eliminating unnecessary steps, rather than shortening the actual time required to conduct scientific and regulatory reviews or longer work hours. All units, including the Institutional Review Board, were represented on the project team, thereby ensuring that TACT did not affect the protection of human subjects.

Challenging several assumptions in the existing processes, the TACT project actualized meaningful and sustainable change and harmonized procedures across all 3 Mayo Clinic sites. For example, before TACT, radiation safety reviews were conducted separately at each campus for a 3-site study because of differences in state laws. Through effective collaboration, each site’s radiation safety officers agreed on standard committee intake forms and a single videoconference Radiation Safety review meeting that satisfied all state laws. Indeed, within TACT, all Mayo Clinic sites have an identical timeline (Figure 1), scientific review processes, and, where possible, a single review and legal contract for all sites. Nonetheless, there are differences in the organization of study teams, expenses, and some processes among 3 sites, which may explain why it took longer to activate multi-site studies.

In the United States, the protocol, scientific review process, business and legal requirements for multicenter clinical trials are similar across institutions. Hence, the TACT process flow and timeline should be widely implementable, aided by other new nationwide initiatives (eg, Accelerated Clinical Trial Agreements, Smart IRB) that employ uniform, and often one, process across institutions for multi-center trials. Facilitating these studies cost $148,262, which is modest and less than 0.5% of the contracted (not earned) revenue of $38,669,301. Over time, processes have been refined and streamlined; facilitation is more efficient and costs less. While the TACT process is now defined, implementing TACT in other institutions will require teamwork, disciplined project management, the ability to challenge assumptions, and a compulsive reliance on data and metrics.

It took 3 months to build a team that took ownership of the problem and for team members to recognize that the pre-TACT process was broken but could be revamped. Comingling principal investigators, research coordinators, managers, and directors from business units fostered joint ownership in the TACT team. Through active discussion and examples, the principal investigators shared their experiences and the pitfalls of the existing process (e.g. patients who sought access to clinical trials at other institutions because of delayed activation at our institution and of multisite trials that were closed to enrollment shortly after activation at our institution - a considerable expenditure for the institution without the benefit of enrolling even 1 participant).

Before TACT, efforts by individual business units to shorten their turnaround times failed because the units worked in isolation and redefined their inputs. For example, previously, the IRB agreed to reduce its process time provided submissions were pristine. However, these improvements did not shorten the overall activation time because additional time was required to proof the documents before IRB submission. Further, when business units work in isolation, opportunities to eliminate steps or move steps from sequential to parallel can be missed. One striking example was a long-standing practice of not executing contracts until IRB approval was obtained. Legal Contract Administration (LCA) was concerned that IRB members may feel coerced to approve an application if a contract was already signed. The IRB believed that the protocol could not be changed after contracts were signed. Through discussion, LCA learned that IRB members were not aware of contract status during their review and thus LCA was comfortable with signing the contracts prior to IRB approval, including contingencies in the contract to address failure of IRB approval, eliminating several days from the process.

The addition of a trained project manager (or facilitator) to each trial was the change that had the most impact on the process. Earlier efforts, which focused on reducing the actual work time for individual steps, did not meaningfully reduce the overall activation time because the total actual work time was only approximately 60 hours over several months. Rather, TACT, and specifically the facilitator, focused on reducing wait and rework time. By aligning the multidisciplinary activation team toward a shared schedule, the facilitator ensured the trial flowed through the activation process without unnecessary delays.

Finally, TACT introduced a web-based application that provides real-time updated information on timelines and metrics for each study, accessible to all study staff and business units. This transformation provided transparency to the activation process.

Impact

The outcome of TACT is aligned with the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative, which emphasized the need to minimize delays in study start-up time.(5) Likewise, the European Union’s Clinical Trial Regulation EU 536/2014, effective 2019, specifically calls for the avoidance of administrative delays for starting a clinical trial with a procedure that is “flexible and efficient, without compromising patient safety or public health.”(6) The TACT process is focused on the activating clinical trials in a timely manner rather than on the design or the conduct of clinical trials, which also needs to be streamlined. While this project was limited to industry-funded trials, it is currently being extended to trials supported by other sponsors. By comparison to industry-funded studies, the ACT process for federally-funded trials begins after funding is received; the process and timeline need to more flexible.

Supplementary Material

Times for Individual Steps in TACT

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported in part by Grant Number 1 UL1 RR024150-01* from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. The funding source had no involvement with the study design; collecting, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviations

- ACT

accelerated clinical trial

- IQR

interquartile range

- IRB

institutional review board

- PDSA

plan-do-study-act

- TACT

transforming the activation of clinical trials

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: There are no personal financial interests to declare.

References

- 1.Nass S, Moses H, Mendelsohn J. A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. National Academies Press; Washington (DC): 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler J, et al. Improving cardiovascular clinical trials conduct in the United States: recommendation from clinicians, researchers, sponsors, and regulators. Am Heart J. 2015;169:305–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langley G, Moen R, Nolan K, Nolan T, Norman C, Provost L. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. 1. Jossey-Bass Publishers; San Francisco (CA): 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dilts DM, Sandler AB. Invisible barriers to clinical trials: the impact of structural, infrastructural, and procedural barriers to opening oncology clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4545–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed 9/7/17];Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (U19) 2009 < https://www.fda.gov/scienceresearch/specialtopics/criticalpathinitiative/spotlightoncpiprojects/ucm167886.htm>.

- 6.European Parliament and Council. [Accessed 9/7/17];Regulation (EU) no 536/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on Clinical Trials on Medicinal Products for Human Use, and repealing Directive 2001/20/EC. 2014 < https://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol-1/reg_2014_536/reg_2014_536_en.pdf>.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Times for Individual Steps in TACT