Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of fractional carbon dioxide laser use in the treatment of mature burn scars. DESIGN: This was an uncontrolled, open-label clinical trial. SETTING: The setting for this study was Dermatology Department at Cairo University in Cairo, Egypt. PARTICIPANTS: Twenty patients with mature burn scars were included in the study. MEASUREMENTS: Three fractional carbon dioxide laser sessions were given, 4 to 8 weeks apart. Primary outcome was measured using two scar scales, the Vancouver Scar Scale and the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale. Secondary outcomes included evaluation of collagen and elastic fibers using routine hematoxylin and eosin, Masson’s trichrome, and orcein stains. Outcomes were measured two months after the last laser session. RESULTS: Both Vancouver Scar Scale and Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale showed significant reduction following treatment (p<0.001). Scar relief and pliability improved most followed by vascularity. Pigmentation improved the least. Percent improvement in Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale patients’ overall assessment was 44.44 percent. The pattern and arrangement of collagen and elastic fibers showed significant improvement (p<0.001, p=0.001, respectively), together with significant improvement in their amounts (p=0.020, p<0.001, respectively). No significant correlation existed between clinical and histopathological/histochemical scores. Side effects and complications were mild and tolerable. CONCLUSION: Fractional carbon dioxide laser use is an effective and safe method for treating burn scars with a significant change in the opinion of the patients about their scar appearance.

Keywords: Fractional carbon dioxide (CO2) laser, burn scars, collagen, elastic fibers, Masson’s trichrome, orcein

Burn scars represent a major challenge in clinical and aesthetic dermatology. In addition to their significant morbidity, the side effects and lengthy courses of many therapeutic modalities for the treatment of burn scars place an additional burden on the patients.1

Conventional ablative lasers, particularly conventional erbium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet laser, erbium YAG (Er:YAG) and conventional CO2 lasers have been proven to be very effective in scar treatment by ablating the bulk of the tissue and inducing collagen remodeling and regenerative mechanisms.2 However, the associated side effects and prolonged recovery period can limit patient satisfaction with these devices.3

With the introduction of fractional photothermolysis, fractional ablative lasers have combined the impressive results of ablative lasers with the low side effects profile of nonablative lasers.3 The use of fractional ablative CO2 laser in treating burn scars has increased, with some investigators considering it to be the treatment of choice, particularly for scars due to third-degree burns. Fractional ablative CO2 lasers are considered superior to fractional nonablative lasers due to their ability to release contracted scars and their unique chemical pathways that contribute to proper healing.4

The aim of this present study was to assess the efficacy of fractional ablative CO2 lasers in the treatment of mature burn scars according to clinical, histopathological, and histochemical perspectives.

METHODS

This uncontrolled, open-label clinical trial was approved by the Dermatology Department Research Ethical Committee (DermaREC) of the Cairo University in Cairo, Egypt, and informed consent forms were signed by enrolled subjects.

Subjects. Subjects with burn scars presenting to the outpatient clinic of the Dermatology Department at Cairo University from March 2014 to August 2014 were screened for eligibility of enrollment in the trial. Included in the trial were subjects with at least 20cm2 burn scars that were at least one year old. Subjects who received any form of treatment (specifically systemic retinoids) within the past six months, with a previous history of adverse outcomes related to laser therapy, or with a contraindication to treatment with fractional CO2 laser were excluded. Also, subjects with burn scars present only in the head and neck areas were excluded. Ultimately, twenty patients (16 women [80%] and 4 men [20%]; mean ± standard deviation [SD] age: 26.35±9.85 years, range: 13–50 years) were enrolled. Information on cause, site, duration of the burn scars, and previous treatment modalities used was documented for each subject.

Laser treatment. The target scars underwent three treatment sessions using a fractional ablative 10,600 nm CO2 laser (SmartXide DOT®; DEKA, Florence, Italy). Sessions were performed 4 to 8 weeks apart. Topical anesthesia (lidocaine 2.5% and prilocaine 2.5%) was applied to the target area 30 to 60 minutes before the procedure, and then the area was washed off and properly dried before laser application. The following parameters were used in a single pass (in all cases): stacking, 3; power, 18 Watts; dwell time, 600µsec; and spacing, 200µm. Post-laser home treatment included topical application of panthenol 2% twice daily for four weeks. Patients were also instructed to use sunscreen regularly (for scars in sun-exposed sites) and to avoid removal of the crust.

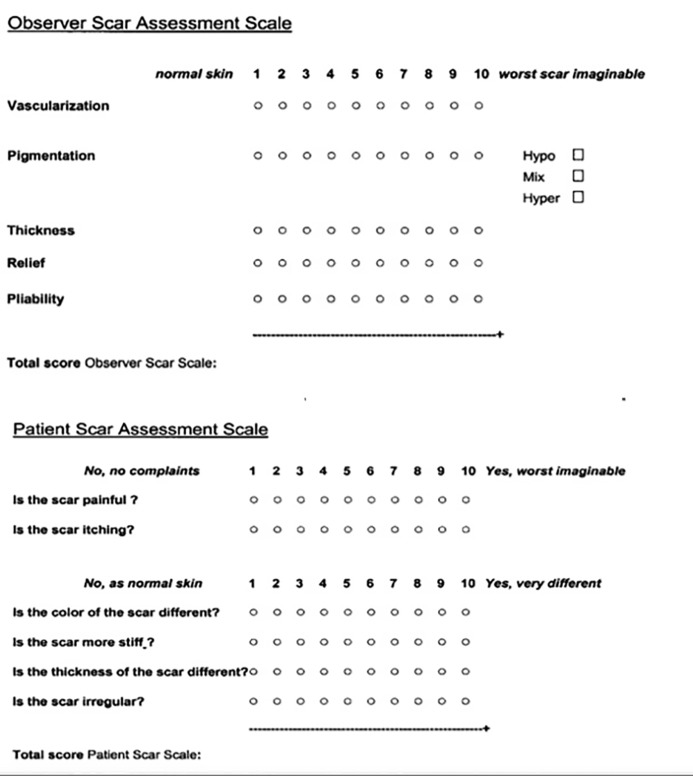

Primary outcome measures. The Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) (Table 1)1,5 and the Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS) (Figure 1)6,7 were used for measuring primary outcome. Both were calculated at baseline and two months after the last laser treatment. The principal investigator calculated the VSS score and the observer’s portion of the POSAS. Each participating subject completed the patient’s portion of the POSAS. Patient overall assessment scores on a scale from 1 to 10 were also calculated.6 Total POSAS scores were then calculated.

TABLE 1.

Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS)1

| 1. PIGMENTATION | 2. VASCULARITY |

|---|---|

| 0= Normal color (resembles nearby skin) | 0= Normal |

| 1= Hypopigmentation | 1= Pink |

| 2= Hyperpigmentation | 2= Red |

| 3= Purple | |

| 3. PLIABILITY | 4. HEIGHT (MM) |

| 0= Normal | |

| 1= Supple (flexible with minimal resistance) | |

| 2= Yielding (giving way to pressure) | |

| 3= Firm (solid/inflexible, not easily moved, resistant to manual pressure) | 0= Normal (flat) 1= <2mm |

| 4= Banding (rope-like, blanches with extension of scar, does not limit range of motion) | 2= >2mm and <5mm 3= >5 mm |

| 5= Contracture (permanent shortening of scar producing deformity or distortion, limits range of motion) |

FIGURE 1.

Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale (POSAS)

Secondary outcome measures. Secondary outcomes included histological and histochemical evaluation of collagen and elastic fibers. A pre-treatment, 4mm punch biopsy was taken from the target scar of each subject and the site of the biopsy was marked and photographed. A post-treatment biopsy was taken adjacent to the pre-treatment biopsy two months after the last laser treatment. Biopsies were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin blocks. Sections were prepared for routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Masson’s trichrome staining for collagen fibers, and orcein staining for elastic fibers. All sections were examined using a Primo Star™ microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) with an integrated camera by which photomicrographs depicting the various histopathological and histochemical findings were obtained.

Routinely stained H&E sections and orcein stained sections were blindly graded with regard to the appearance and pattern of dermal collagen and the appearance of dermal elastic tissue (Table 2).7 Collagen fibers in Masson’s trichrome-stained sections and elastic fibers in orcein-stained sections were quantitatively evaluated using image analysis by measuring the area percent of blue color and black color at magnification × 100 in five nonoverlapping fields using the Leica QWin image analysis software (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

TABLE 2.

Scoring of collagen fibers (routine H&E stain) and elastic fibers (Orcein stain)7

| SCORE | COLLAGEN FIBERS | ELASTIC FIBERS |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Normal | Normal |

| 1 | Collagen is fine and fibrillar | Short fragmented elastic fibers |

| 2 | Combination of 1 and 3 | Intermediate between 1 and 3 |

| 3 | Collagen is fibrotic, vessels are perpendicular to the epidermis | Fibrillar eleastic fibers, parallel to the epidermis |

| 4 | Combination of 3 and 5 | Intermediate between 3 and 5 |

| 5 | Collagen is extremely sclerotic and compacted in thick bundles | Absent or nearly absent |

Monitoring of side effects or complications. Patients were assessed at each laser session and at the end of the study for any side effects, including prolonged erythema (erythema lasting more than 3 days), pain (using a 0–10 visual analog scale, where 0=no pain and 10=worst imaginable pain, with mild pain scored 1–3, moderate pain scored 4–6, and severe pain scored 7–10), swelling, infection, hyperpigmentation, and hypopigmentation.

Statistical methods. Data were statistically described in terms of mean ± SD and range or frequencies (number of cases) and percentages, when appropriate. Comparison between preand post-treatment values was done using paired t-tests in normally distributed data and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired (matched) samples, when data were not normally distributed. The comparison between VSS and POSAS items was done using the Freidman test with post-hoc multiple pairwise comparison tests. The comparison between different scar sites was done using Kruskal-Wallis test. Correlation between various variables was evaluated using the Pearson moment correlation equation for linear relation in normally distributed variables and Spearman’s rank correlation equation for non-normal variables/non-linear monotonic relation. P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All statistical calculations were done using computer program SPSS version 15 for Microsoft Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, United States)

RESULTS

The cause of burn scars included thermal burns from heated fluids in 11 patients (55%) and fire in nine patients (45%). Treated burn scars were located on the arms in 14 patients (70%), the thighs in two patients (10%), the chest in two patients (10%), the breast in one patient (5%), and the abdomen in one patient (5%). Scar duration ranged from 1 to 30 years (mean: 12.30±8.70 years). Previous treatment modalities included intralesional steroids, grafting, surgical release, and topical treatment (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Clinical data of the patients

| NO. | AGE (years) | SEX | SCAR DURATION (years) | BURN TYPE | SITE | FITZPATRICK SKIN TYPE | PREVIOUS TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | F | 3 | Scald | Thigh | III | none |

| 2 | 23 | F | 10 | Fire | Arm | III | none |

| 3 | 20 | F | 3 | Scald | Arm | IV | Intralesional steroids |

| 4 | 31 | F | 2 | Fire | Arm | II | Intralesional steroids |

| 5 | 15 | M | 2 | Scald | Arm | V | none |

| 6 | 29 | F | 19 | Fire | Arm | III | none |

| 7 | 46 | M | 2 | Fire | Arm | IV | Intralesional steroids |

| 8 | 19 | F | 17 | Scald | Arm | IV | none |

| 9 | 27 | F | 1 | Fire | Breast | III | none |

| 10 | 18 | F | 10 | Scald | Abdomen | III | none |

| 11 | 22 | M | 15 | Scald | Arm | IV | Topical therapies |

| 12 | 40 | F | 5 | Fire | Chest | IV | none |

| 13 | 32 | F | 30 | Scald | Arm | II | Grafting |

| 14 | 27 | F | 12 | Fire | Arm | III | none |

| 15 | 26 | F | 21 | Fire | Thigh | III | none |

| 16 | 13 | F | 12 | Scald | Arm | III | Surgical release |

| 17 | 18 | F | 17 | Scald | Arm | III | none |

| 18 | 20 | F | 20 | Scald | Arm | II | none |

| 19 | 50 | F | 24 | Fire | Chest | III | none |

| 20 | 21 | M | 21 | Scald | Arm | IV | none |

Seventeen patients completed the entire treatment and follow-up protocol. One patient dropped out after the second treatment session due to personal issues and two patients were not able attend the final follow-up session (which ocurred two months after the last session) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

A flow chart demonstrating the subjects recruited in the study

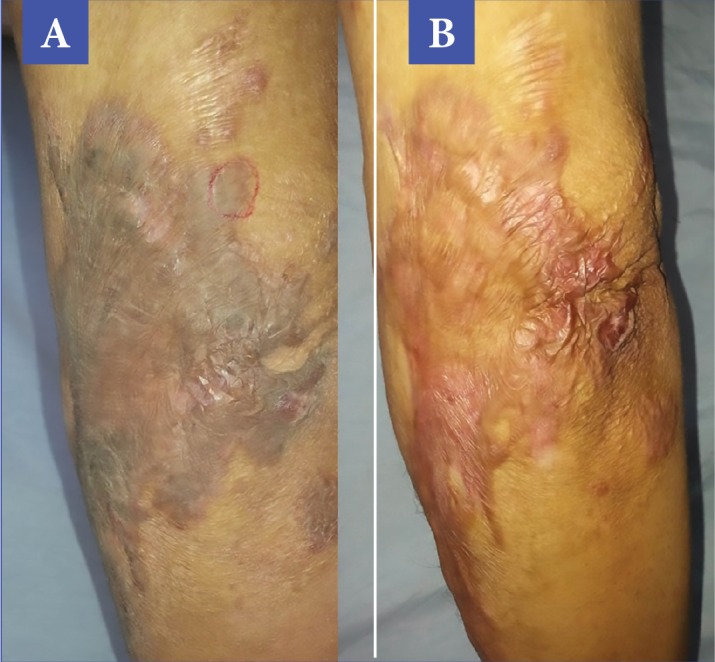

Clinical results. Primary outcome scores showed significant reduction (p<0.001) (Figure 3, Table 4). The percentage improvement of each score is listed in Table 5. The percentage improvement in each variable of VSS is listed in Table 6, with pliability being the most significantly improved item (p<0.0001). The percentage improvement in each variable of the POSAS is listed in Table 7, with relief being the most significantly improved item (p=0.0071).

FIGURE 3.

Demonstration of clinical response, before treatment (A) and after treatment (B)—The patient showed a 31% improvement in VSS and a 40 percent improvement in total POSAS, with relief being the most improved parameter.

TABLE 4.

Results of VSS, total POSAS, and POSAS patients’ overall assessment before and after treatment

| SCALE | RANGE | MEAN±SD |

|---|---|---|

| Total POSAS | ||

| Before treatment | 5–11 | 7.76±2.07 |

| After treatment | 2.5–7 | 5.18±1.18 |

| P value* | <0.001 | |

| Total POSAS | ||

| Before treatment | 51–87 | 65.71±11.23 |

| After treatment | 26–56 | 38.35±9.92 |

| P value* | <0.001 | |

| POSAS patient overall assessment | ||

| Before treatment | 6–10 | 3–7 |

| After treatment | 9.12±1.26 | 5.12±1.16 |

| P value* | <0.001 | |

VSS: Vancouver Scar Scale: POSAS: Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale; SD: standard deviation

p value significant if less than 0.05

TABLE 5.

Percentage improvement in VSS, total POSAS, and POSAS patients’ overall assessment

| SCALE | RANGE | MEAN±SD |

|---|---|---|

| VSS | 0–38.46 | 19.90±12.17 |

| Total POSAS | 12.12–40.91 | 27.62±7.75 |

| POSAS patient overall assessment | 11.11–66.66 | 44.44±12.42 |

VSS: Vancouver Scar Scale; POSAS: Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale; SD: standard deviation

TABLE 6.

Percentage improvement in each variable in Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS)

| VARIABLE | RANGE | MEAN±SD |

|---|---|---|

| Pigmentation | 0.0–0.0 | 0.00±0.00 |

| Vascularity | -(50.0)–100.0 | 39.21±46.00 |

| Pliability | 0–100.0 | 53.43±22.26 |

| Height | 0–100.0 | 29.4±30.92 |

| p value* | < 0.0001 | |

SD: standard deviation

p value significant if <0.05

TABLE 7.

Percentage improvement in each variable in Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale Observer Scale

| VARIABLE | RANGE | MEAN±SD |

|---|---|---|

| Vascularity | -(50.0)–80.0 | 38.25±31.43 |

| Pigmentation | -(10.0)–66.7 | 37.07±19.81 |

| Thickness | 10.0–66.7 | 47.42±14.66 |

| Relief | 21.4–66.7 | 53.43±11.18 |

| Pliability | 33.3–78.6 | 49.06±13.99 |

| p value* | 0.0071 | |

SD: standard deviation

p value significant if <0.05

Scar duration negatively influenced the percentage improvement in VSS, but not the percentage improvement in total POSAS (r= -0.608, p=0.010 and r= -0.465, p=0.06, respectively). However, neither the age of the patient nor site of the scar affected the percentage improvement of both scores.

Prolonged erythema was experienced by four patients (23.5%). Seven patients experienced pain following the laser session, with four patients (23.5%) experiencing mild pain and three patients (17.6%) experiencing moderate pain. The pain was generally tolerable, lasting 1 to 6 days (mean: 2.71±1.70 days). Transient swelling following sessions was experienced by three patients (17.6%) lasting from 1 to 3 days (mean: 2±1 days). Hyperpigmentation developed in three patients (17.6%) and improved with the application of topical bleaching creams. Hypopigmentation developed in two patients (11.8%) and was persistent at the two-month follow-up visit. One patient experienced lightening of her scar, where the treated area appeared lighter as a consequence of rejuvenation of the skin.

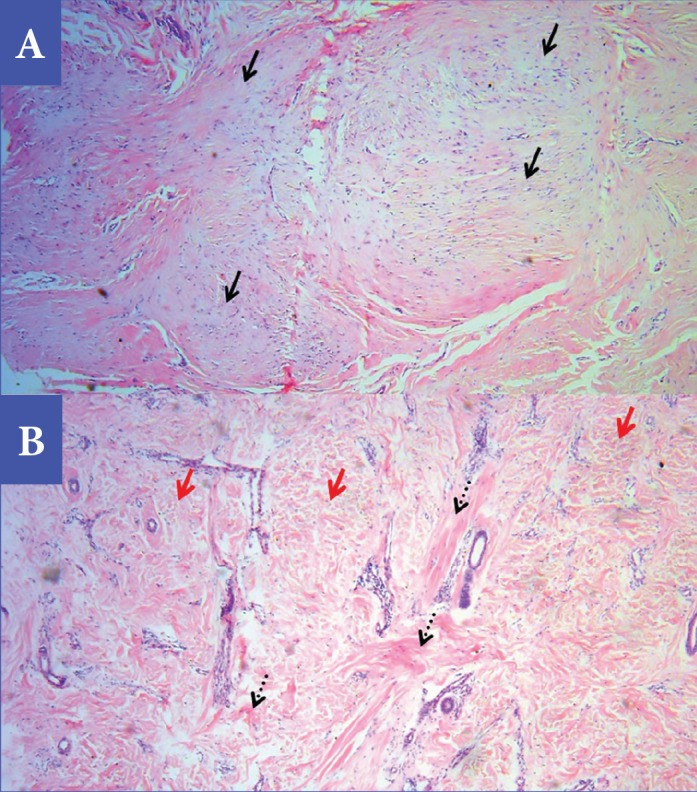

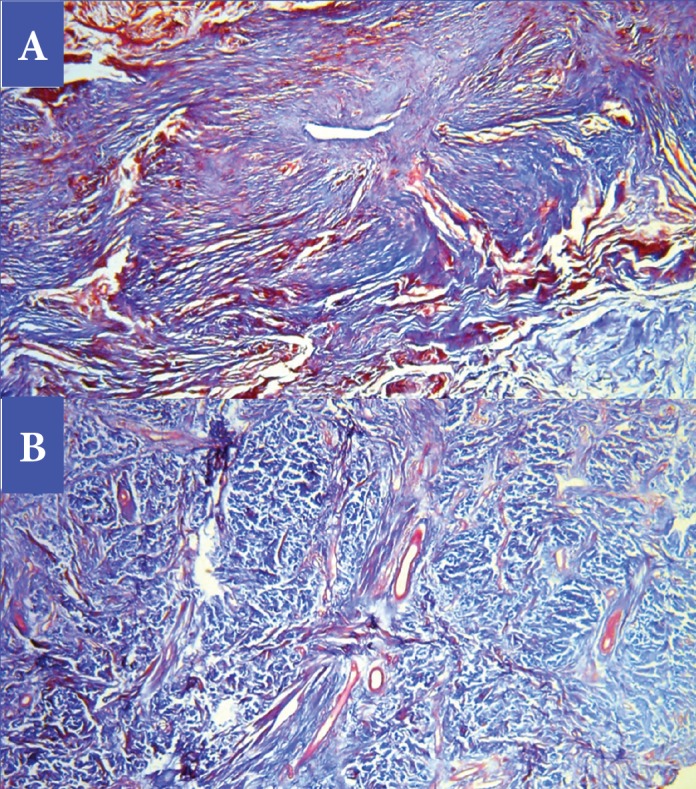

Histopathological and histochemical results. After treatment, both the H&E grading score of collagen fibers and the area percentage of collagen fibers (stained with Masson’s trichrome) showed a significant reduction (i.e., improvement) (p<0.001 and p=0.020, respectively) (Table 8, Figures 4 and 5). The orcein stain grading score showed a significant reduction (i.e., improvement) and the mean area percentage of elastic fibers (based on orcein stain results) showed a significant increase (i.e., improvement) after treatment (p=0.001 and p<0.001 respectively) (Table 9, Figure 6).

TABLE 8.

Comparison of H&E grading score and mean area percent of collagen (Masson’s trichrome) before and after treatment

| STAIN | RANGE | MEAN±SD |

|---|---|---|

| H&E grading score of collagen fibers | ||

| Before treatment | 2–5 | 4.12±0.78 |

| After treatment | 2–4 | 2.71±0.92 |

| p value* | < 0.001 | |

| Mean area % of collagen (Masson’s trichrome) | ||

| Before treatment | 6.44–35.19 | 18.69±7.70 |

| After treatment | 2.62–21.64 | 11.52±6.16 |

| p value* | 0.020 | |

H&E: haemotoxylin and eosin; SD: standard deviation

p value significant if <0.05.

FIGURE 4.

Photomicrographs demonstrating histopathological grading of collagen fibers using routine H&E stain, before treatment (A) and after treatment (B)—The thick sclerotic collagen bundles (solid black arrows) in the scar tissue before treatment (Grade 5) changed to a combination of fibrotic (dotted black arrows) and fibrillar (red arrows) collagen, with vessels starting to appear in the scar tissue perpendicular to the epidermis after treatment (grade 2) (H&E staining original magnification × 40).

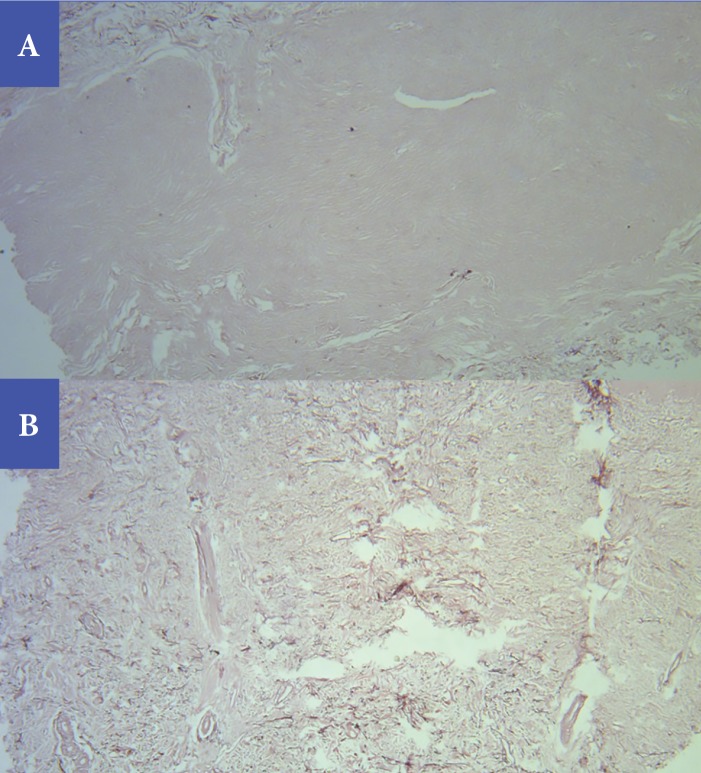

FIGURE 5.

Photomicrographs representing results of Masson’s trichrome staining for collagen fibers for the same case presented in Figure 4, before treatment (A) and after treatment (B)—Reduction in collagen density (16% by image analysis) and improved collagen quality. (Masson’s trichrome stain, original magnification × 40).

TABLE 9.

Comparison of orcein stain grading score and the mean area % of elastic fibers (orcein stain) before and after treatment.

| STAIN | RANGE | MEAN ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Orcein stain grading score | ||

| Before treatment | 2–5 | 3.71±1.26 |

| After treatment | 1–5 | 2.88±1.31 |

| p value* | 0.001 | |

| Mean area % of elastic fibres (orcein stain) | ||

| Before treatment | 0.17–3.65 | 1.41±0.97 |

| After treatment | 2.46–13.75 | 7.06±3.30 |

| p value* | <0.001 | |

SD: standard deviation

p value significant if <0.05.

FIGURE 6.

Photomicrographs representing results of orcein staining for elastic fibers for the same case presented in Figure 4, before treatment (A) and after treatment (B). Elastic fibers were completely absent from the scar tissue before treatment (Grade 5). Following treatment, elastic fibers started to appear as a combination of short fragmented and fibrillar fibers (Grade 2) (Orcein stain, original magnification × 40).

Clinicopathological correlations. The percentage improvement in the H&E grading score of collagen fibers and the percentage improvement in the mean area percentage of collagen showed no significant correlation with the percentage improvement in VSS (r= -0.268, p=0.313 and r= -0.084, p=0.749, respectively) or total POSAS (r= 0.169, p=0.517 and r= -0.112, p=0.669, respectively). Similarly, the percentage improvement in elastic fibers grading score and the percentage improvement in mean area percentage of elastic fibers showed no significant correlation with the percentage improvement in VSS (r=0.28, p=0.276 and r=0.212, p=0.414, respectively) or total POSAS (r=0.393, p=0.119 and r=0.476, p=0.053, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Objective measures showed significant improvement of the burn scars following fractional CO2 laser treatment and a significant change in the opinion of the patients about their scar appearance. This was in agreement with the findings of several researchers using different parameters.4,7–10

In the current study, improvement was significantly higher for relief and pliability, followed by vascularity and pigmentation. This was similar to the finding by Kim et al,11 who reported that ablative fractional CO2 laser use was more effective in improving pliability and thickness of surgical scars, while pulsed dye laser (PDL) use was superior regarding treating vascularity and pigmentation. This suggests that firm, irregular scars are the best candidates to respond to fractional CO2 laser use rather than erythematous, hyperpigmented ones. The initial management of hyperemic scars by PDL targeting the vasculature, followed by the fractional CO2 laser, might be a more suitable plan for managing hyperemic scars.

The significant improvement in scar thickness, pliability, and relief achieved by fractional CO2 use in our study was shown by histological and histochemical analysis to be due to its effect on collagen and elastic fibers.

The irregular sclerotic collagen fibers significantly changed to less sclerotic, finer, more fibrillar collagen, with a significant reduction in the amount of collagen fibers assessed morphometrically. Our findings were in agreement with Ozog et al,7 Makboul et al,12 and El-Zawahry et al.10 Fractional CO2 laser induces matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which clear the damaged collagen and allow for collagen remodeling to take place, with the formation of new, healthy collagen.13 Similar effects were reported after fractional ablative and nonablative Er:YAG treatment of photodamaged skin.14 A significant improvement in the grading score of elastic fibers was detected in the current study, and morphometrically, the amount of elastic fibers increased significantly after treatment. Although not statistically significant, Ozog et al reported similar changes.7 In contexts other than burn scars, Shin et al reported increased density of elastic fibers following fractional CO2 laser treatment of striae distensae.15 Also, Jiang et al performed a single pass fractional CO2 laser session on mice dorsal skin and detected the replacement of lumps of old elastic fibers by slender elastic fibers with a wider distribution within few hours of fractional CO2 resurfacing.16

Improvement in scar vascularity by fractional CO2 lasers occurred in our cases and this might be explained by the dermal blood vessels becoming less trapped and more perpendicular to the epidermis as a result of collagen remodeling. This observation was also reported by both Ozog et al7 and Makboul et al.12

In accordance with El-Zawahry et al,10 our study showed no correlation between clinical and histological indices. This probably indicates that the clinical improvement in burn scars does not depend solely on the improvement of the arrangement and the amount of collagen and elastic fibers. It can be presumed that complex biochemical pathways elicited by fractional CO2 laser, including changes at the cytokine level, also contribute to an improvement in scar pigmentation, vascularity, and patients’ perception of their scars.

We found that the shorter the scar duration, the better the improvement with fractional CO2 laser. This finding is reiterated in the observation reported by Niwa et al, stating that scars less than one year in duration improve more noticeably.17 This is mostly due to the effect of cytokines and growth factors that influence fibroblast activity early on in wound healing. On the other hand, neither the age of the patient, nor the scar site have been found to influence the percentage of clinical improvement. Haedersdal et al18 found no differences in the efficacy of treatment with respect to subject age, anatomical location of the scar, or duration of the scar. In treating different types of scar, El Taweel and Abd El-Rahman found that clinical improvement was better in younger patients.19

Regarding side effects and complications, the pain was generally tolerable.

Hyperpigmentation was observed in three patients (17.6%), with skin type III. This was mostly attributed to the close spacing and non-adjuvant use of bleaching agents. El Taweel and Abd El-Rahman19 reported the development of hyperpigmentation in three out of 25 patients with mature scars (12%) treated by fractional CO2 laser. As in our cases, hyperpigmentation improved with bleaching agents. In the current study, one patient experienced a significant lightening of her scar, which can be a consequence of skin rejuvenation.20 Actual hypopigmentation developed in only two cases (11.7%). In one patient, it was in the form of a widening of an initially hypopigmented area, which may have been attributed to deep stacking causing thermal injury. The other case developed hypopigmentation following early removal of the crust by the patient. The incidence of hypopigmentation in the current study is much lower than that reported by Salles et al.21 Generally, the developed side effects did not affect patients’ satisfaction with the achieved results as indicated by significant reduction in POSAS patients’ overall assessment scores.

In conclusion, fractional CO2 laser can be an effective and safe modality in the treatment of post-burn scars. It achieves significant change in the opinion of the patients about their scar appearance. Limitations of our study included its small sample size and the relatively short follow-up period. More sessions are needed to reach the ultimate response. Wider spacing can be used to avoid confluent thermal damage and reduce side effects. The concomitant use of bleaching creams can also reduce the incidence of hyperpigmentation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brusselaers N, Pirayesh A, Hoeksema H et al. Burn scar assessment: a systematic review of different scar scales. J Surg Res. 2010;164(1):e115–e123. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanzi EL, Alster TS. Single-pass carbon dioxide versus multiple-pass Er:YAG laser skin resurfacing: a comparison of postoperative wound healing and side-effect rates. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(1):80–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexiades-Armenakas MR, Dover JS, Arndt KA. The spectrum of laser skin resurfacing: nonablative, fractional, and ablative laser resurfacing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5):719–737. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waibel J, Beer K. Ablative fractional laser resurfacing for the treatment of a third-degree burn. J Drug Dermatol. 2009;8(3):294–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan T, Smith J, Kermode J et al. Courtemanche DJ. Rating the burn scar. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1990;11(3):256–260. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draaijers LJ, Tempelman FR, Botman YA et al. The patient and observer scar assessment scale: a reliable and feasible tool for scar evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(7):1960–1967. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000122207.28773.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozog DM, Liu A, Chaffins ML et al. Evaluation of clinical results, histological architecture, and collagen expression following treatment of mature burn scars with a fractional carbon dioxide laser. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(1):50–57. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamadermatol.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qu L, Liu A, Zhou L et al. Clinical and molecular effects on mature burn scars after treatment with a fractional CO(2) laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2012;44(7):517–524. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clementoni MT, Patel T. A new treatment for severe burn and post-traumatic scars: a preliminary report. Treatment Strategies - Dermatology. 2013;2(2):44–48. [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Zawahry BM, Sobhi RM, Bassiouny DA, Tabak SA. Ablative CO2 fractional resurfacing in treatment of thermal burn scars: an open-label controlled clinical and histopathological study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2015;14(4):324–331. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim DH, Ryu HJ, Choi JE et al. A comparison of the scar prevention effect between carbon dioxide fractional laser and pulsed dye laser in surgical scars. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(9):973–978. doi: 10.1097/01.DSS.0000452623.24760.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makboul M, Makboul R, Abdelhafez AH et al. Evaluation of the effect of fractional CO2 laser on histopathological picture and TGF-β1 expression in hypertrophic scar. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014;13(3):169–179. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reilly MJ, Cohen M, Hokugo A et al. Molecular effects of fractional carbon dioxide laser resurfacing on photodamaged human skin. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2010;12(5):321–325. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2010.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borges J, Cuzzi T, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA et al. Fractional Erbium laser in the treatment of photoaging: randomized comparative, clinical and histopathological study of ablative (2940nm) vs. non-ablative (1540nm) methods after 3 months. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(2):250–258. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin JU, Roh MR, Rah DK et al. The effect of succinylated atelocollagen and ablative fractional resurfacing laser on striae distensae. J Dermatologic Treat. 2011;22(2):113–121. doi: 10.3109/09546630903476902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang X, Ge H, Zhou C et al. The role of transforming growth factor β1 in fractional laser resurfacing with a carbon dioxide laser. Lasers Med Sci. 2014;29(2):681–687. doi: 10.1007/s10103-013-1383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niwa AB, Mello AP, Torezan LA et al. Fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of hypertrophic scars: clinical experience of eight cases. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(5):773–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haedersdal M, Moreau KE, Beyer DM et al. Fractional nonablative 1540nm laser resurfacing for thermal burn scars: a randomized controlled trial. Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41(3):189–195. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Taweel AI, Abd El-Rahman SH. Assessment of fractional CO2 laser in stable scars. Egypt J Dermatol Venerol. 2014;34:74–80. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chwalek J, Goldberg DJ. Ablative skin resurfacing. In: Bogdan Allemann I, Goldberg DJ., editors. Basics in Dermatological Laser Applications. Karger Publishers; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salles AG, Remigio AFDN, Zacchi VBL et al. Treatment of facial burn sequelae using fractional CO2 lasers in patients with skin phototypes III to VI. Brazilian Journal of Plastic Surgery. 2012;27(1):9–13. [Google Scholar]