Abstract

Background

In clinical practice, translating the benefits of a sustained physically active lifestyle on glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is difficult. A walking prescription may be an effective alternative.

Aim

To examine the effect of a 10 000 steps per day prescription on glycaemic control of patients with T2DM.

Design and setting

Forty-six adults with T2DM attending a general outpatient clinic were randomised into two equal groups. The intervention group was given goals to accumulate 10 000 steps per day for 10 weeks, whereas the control group maintained their normal activity habits.

Method

Daily step count was measured with waist-mounted pedometer and baseline and endline average steps per day. Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c), anthropometric, and cardiovascular measurements were also obtained. An intention-to-treat analysis was done.

Results

The average baseline step count was 4505 steps per day for all participants, and the average step count in the intervention group for the last 4 weeks of the study period was higher by 2913 steps per day (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1274 to 4551, F (2, 37.7) = 18.90, P<0.001). Only 6.1% of the intervention group participants achieved the 10 000 steps per day goal. The mean baseline HbA1c was 6.6% (range = 5.3 to 9.0). Endline HbA1c was lower in the intervention group than in the control group (mean difference −0.74%, 95% CI = −1.32 to −0.02, F = 12.92, P = 0.015) after adjusting for baseline HbA1c. There was no change in anthropometric and cardiovascular indices.

Conclusion

Adherence to 10 000 steps per day prescription is low but may still be associated with improved glycaemic control in T2DM. Motivational strategies for better adherence would improve glycaemic control.

Keywords: blood glucose, general practice, Nigeria, physical activity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, walking

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a common, rapidly increasing non-communicable disease globally, with the greatest burden in low- and middle-income countries where 80% of people with DM live, and where about half of those with the disease remain undiagnosed.1 This places a great burden on the already weak healthcare delivery system of these countries, and a likely challenge in the nearest future.2 Nigeria has a rising prevalence of DM, with a rate of 3.9% in 2010, which may not be unconnected to lifestyle changes.3

Regular physical activity is regarded as one of the cornerstones of lifestyle modification in the prevention and management of DM.4–5 Research has reported that increased physical activity significantly improves blood glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).6–7 Although the benefits of regular physical activities are becoming more widely known, people often find it difficult to incorporate structured exercise into their previously sedentary lives.5 Furthermore, people with DM engage in less physical activities than the general populace, which has also been reported by some Nigerian studies.8–11

Global recommendations require adults to do at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week, over and above their regular baseline activities.12,13 Due to difficulty with achieving these recommendations, research has suggested that increased daily walking may be an effective way of achieving a physically active lifestyle. Walking, a natural, simple, accessible, and effective mode of human movement, is an integral part of nearly all forms of daily locomotion. It is the most commonly reported leisure-time physical activity among adults, which can easily be tailored to individual abilities, lifestyle, and preferences.14 Although an arbitrary target, traced to a Japanese business club >40 years ago, accumulating 10 000 steps per day is believed to be a reasonable estimate of daily activity for healthy adults.15

METHOD

The study was carried out at the General Outpatient Clinic at the University College Hospital in Ibadan, Nigeria, between June and November 2014. The study participants were 46 adult T2DM patients, aged 18–64 years, diagnosed at least 12 months previously in the clinic. They were non-insulin dependent, on dietary control with or without oral hypoglycaemic agents, and could walk without limitations or pain. Pregnant women, smokers, and individuals on prescription medications that might impair ability to walk were excluded from the study. Sample size was calculated with a two-sided statistical superiority design, using a standard deviation and change in HbA1c of 0.87% and 0.75%, respectively, derived from a similar intervention study, at a statistical power of 80% and significance level of 0.05.16

How this fits in

Given the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in Nigeria, low adherence to physical activities, and the paucity of studies examining 10 000 steps per day programmes, it is of interest to study the effect of this popular walking prescription on glycaemic control to provide local evidence on the adherence level and effect on patients with T2DM to this physical activity prescription.

Design and procedures

This study used a randomised design with two conditions: an intervention group with a walking prescription goal of 10 000 steps per day, and a control group who continued with their typical daily activities. All eligible participants were recruited consecutively between June and August 2014, and each received instruction on proper placement and use of pedometer, and manual record of daily step count. They wore a waist-mounted Digi-Walker SW-200 electronic pedometer (Yamax Inc., Tokyo, Japan) during waking hours, removing it only for water-based activities and sleeping.

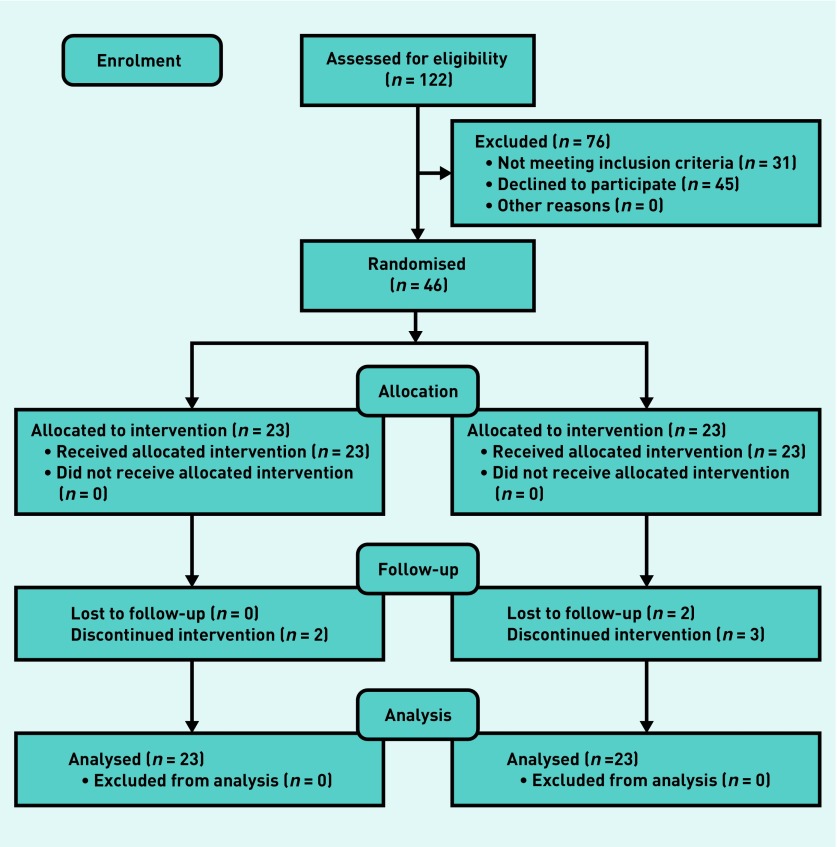

The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. All 46 participants were instructed to record daily step count for an initial 1-week baseline period, while following typical daily activities. Thereafter, at week 1 visit, baseline step counts were recorded. Weight, height, waist and hip circumferences, heart rate, and blood pressure were measured. Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) was measured with the Clover A1c™ analyser (EuroMedix, Leuven, Belgium) and a questionnaire administered. Participants were then randomised into one of two groups (intervention or control) by a simple randomisation method: 46 sealed opaque envelopes (23 identifiers each for intervention and control) were shuffled for each participant to select from a bag. Participants were blinded to the other study conditions.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

The intervention group participants were given the goal of accumulating 10 000 steps per day during the following 10-week intervention period. They were counselled to increase their daily step count by 20% from baseline each week, until the 10 000 steps goal was reached. Possible motivators and barriers to walking were identified. Additional counselling was given at weeks 4 and 8 visit, and telephone follow-up at weeks 2, 6, and 10. Control group participants were asked to maintain their normal activity habits and encouraged to keep daily step count during follow-up. At week 11 visit, baseline measurements were repeated. All measurements and counselling were done by the authors, who were not blinded to the treatment group.

Analysis

Summary statistics are reported as mean ± standard deviation. The primary outcome was the endline HbA1c and secondary outcome was step count. An intention-to-treat analysis was done, and a regression-based multiple imputation method (40 iteration) was adopted to handle missing data in HbA1c and step count measurements, under the assumption of missing at random. The endline HbA1c was compared between the treatment groups, while adjusting for baseline HbA1c, using the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). A linear regression model was used to determine the predictors of HbA1c change in the intervention group only. Analyses done with imputed missing observation are similar to using listwise deletion method. Analysis was performed using SPSS (version 16.00) and STATA/IC (13.1).

RESULTS

Seven of the 46 recruited participants defaulted, as shown in Figure 2. Two of the intervention group participants withdrew consent at weeks 2 and 7. Three participants defaulted at week 1, and one each at weeks 2 and 3 from the control group. Five withdrew consent because of loss of interest in daily step count recording, whereas the other two were lost to follow-up and were unreachable by telephone.

Figure 2.

Recruitment flow diagram.

Participants were aged 33–64 years, with an average age of 53.96 ± 7.7 years. Tables 1 and 2 show the sociodemographic characteristics and baseline clinical parameters of the study participants.

Table 1.

The sociodemographic characteristics of participants by group

| Characteristic type | Subgroup | Intervention, n= 23 | Control, n= 23 | Total, n= 46 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | <40 | 1 | 1 | 2 (4.3) |

| 40–59 | 16 | 16 | 32 (69.6) | |

| 60–64 | 6 | 6 | 12 (26.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Sex | Male | 8 | 9 | 17 (37.0) |

| Female | 15 | 14 | 29 (63.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Religion | Christian | 14 | 16 | 30 (65.2) |

| Islam | 9 | 7 | 16 (34.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Educational level | Below secondary | 7 | 5 | 12 (26.1) |

| Secondary | 5 | 5 | 10 (21.7) | |

| Tertiary | 11 | 13 | 24 (52.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnic group | Yoruba | 20 | 22 | 42 (91.3) |

| Others | 3 | 1 | 4 (8.7) | |

|

| ||||

| Income | <₦18 000 | 1 | 2 | 3 (6.5) |

| ≥₦18 000 | 18 | 16 | 34 (73.9) | |

| Undisclosed | 4 | 5 | 9 (19.6) | |

|

| ||||

| Membership of diabetes association | Yes | 7 | 5 | 12 (26.1) |

| No | 16 | 18 | 34 (73.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Currently living | With family members | 22 | 19 | 41 (89.1) |

| Alone | 1 | 4 | 5 (10.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Duration of diabetes mellitus | <7 years | 16 | 16 | 32 (69.6) |

| ≥7 years | 7 | 7 | 14 (30.4) | |

Table 2.

Baseline clinical parameters of participants

| Clinical parameters | Intervention, mean (SD) | Control, mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 21.73 (3.38) | 23.08 (3.26) | 22.39 (3.35) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 95.69 (11.19) | 97.21 (10.15) | 96.15 (9.65) |

| Waist–hip ratio | 0.939 (0.08) | 0.928 (0.07) | 0.934 (0.07) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 134.28 (20.2) | 125.27 (17.79) | 129.88 (19.4) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 81.17 (10.99) | 79.41 (13.20) | 80.31 (12.02) |

| Heart rate | 84.59 (11.22) | 77.74 (15.68) | 80.97 (14.00) |

SD = standard deviation.

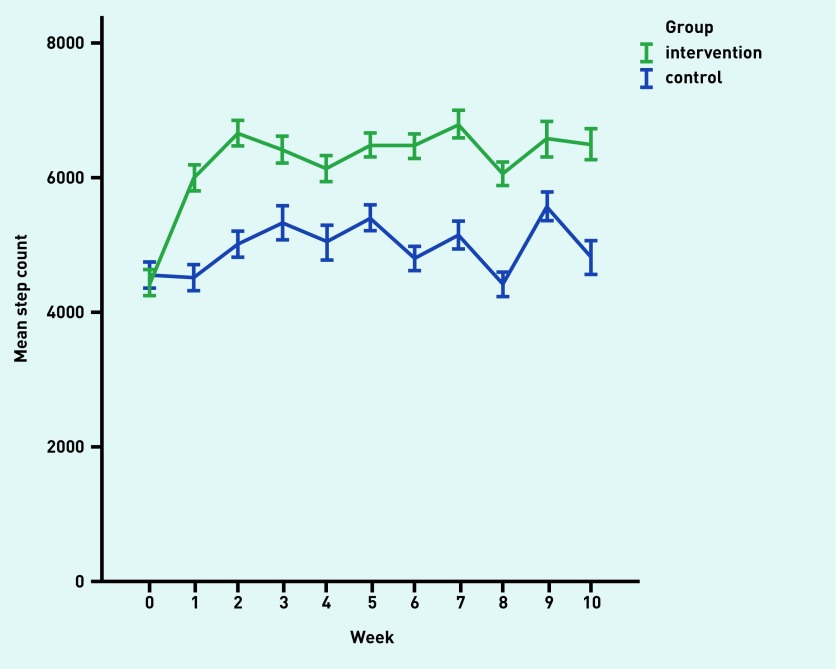

The pattern of step count in the study participants

Figure 3 shows the step count pattern of the study participants. Participants in the intervention and control groups made an average of 4431 ±1822 and 4551 ±2397 steps per day, respectively, at baseline. At the end of week 10, the average daily step count in the intervention and control groups was 6507 ± 2165 steps per day and 4944 ± 2938 steps per day, respectively. The average daily step count in the last 4 weeks of the study period was 6507 ± 1716 steps per day, and 5064 ± 1837 steps per day for the intervention and control groups, respectively. The intervention group step count was higher by 2913 (95% CI = 1274 to 4551, F = 18.90, P = 0.001) compared with the control group when the baseline step count was controlled for with analysis of covariance (ANCOVA).

Figure 3.

Step count pattern of study participants.

In the intervention group participants, the majority (31.2%) achieved an increase of <1000 steps per day; 16.0% achieved step increases of 1000–1999 steps per day; 26.2% of 2000–2999; 20.4% of 3000–3999; and 2.6% achieved ≥5000 steps per day in the study period. In the last 4 weeks of the study period, 6.1% and 18.7% of the intervention group participants achieved an average of 10 000 and 7500 steps per day, respectively.

Pattern of glycosylated haemoglobin, HbA1c, in the study participants

The mean baseline HbA1c was 6.6% (range 5.3–9.0%) for all participants. The endline HbA1c was lower by 0.74% (95% CI = −1.32% to −0.02%, F = 12.92, P = 0.015) in the intervention compared with the control groups, after adjusting for baseline HbA1c levels with ANCOVA, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Analysis of covariance of endline HbA1c of the intervention and control groupsa

| Group | HbA1c baseline (95% CI) | HbA1c endline (95% CI) | Estimated effect size (CI) | F | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 6.84 (6.40 to 7.27) | 6.26 (6.19 to 6.33) | −0.74 (−1.32 to −0.02) | 12.92 | 0.015b |

| Control | 6.36 (5.99 to 6.73) | 6.82 (6.69 to 6.95) |

Dependent variable: HbA1c endline. (HbA1c = glycosylated haemoglobin).

The endline HbA1c was compared between the treatment groups adjusting for baseline HbA1c using ANCOVA.

The baseline HbA1c in the intervention group correlates positively with change in HbA1c (r = 0.30, t = 2.50, P = 0.022), but this association was not sustained in a linear regression model of HbA1c change, which included baseline HbA1c, step count change, age, sex, duration of diabetes, living status, weight, and waist and hip circumferences as independent variables.

Pattern of anthropometric and cardiovascular measurement in the study participants

There was no significant change in the weight, waist circumference, waist–hip ratio, heart rate, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure between the intervention and control groups after the study period.

DISCUSSION

Summary

The study showed that the 10 000 steps per day walking prescription resulted in a 2913 steps per day higher average daily step count among the intervention compared with the control participants in the last 4 weeks of the study period, representing a 64.7% increase from baseline. Adherence was low, with only 6.1% and 18.7% of the intervention participants achieving an average of 10 000 steps per day and 7500 steps per day, respectively. Also, the average endline HbA1c was lower by 0.74% in the intervention compared with the control group, when baseline HbA1c was controlled for with ANCOVA. Although higher baseline HbA1c was associated with better reduction in HbA1c in the intervention group with correlation analysis, this relationship was lost with the inclusion of other probable predictors of change in HbA1c in a linear regression model. Anthropometric and cardiovascular measurements did not change significantly with the intervention.

Despite the participants’ sedentary lifestyle, a 10 000 step count recommendation was associated with significant decrease in HbA1c levels and improved glycaemic control in T2DM individuals. Although attainment of this goal is difficult, individuals with T2DM may still reap health benefits from increases in daily step count over their baseline values. Therefore, some physical activity is still better than none.

Strengths and limitations

This is a single-centre study with little ethnic diversity and may be unrepresentative of the entire Nigerian population, which may reduce the generalisability of the findings. The high attrition rate in a small sample size study is also of concern, but the use of multiple imputation methods to address missing observations from participants and defaulters would help reduce the associated loss of precision, as well as improve validity of the statistical inference of the study. However, the attrition rate may give a true reflection of adherence to the walking prescription in Nigerian clinical practice. Also, participants could have been motivated by the pedometer to increase step count above their habitual level at baseline, as they become aware of their step count. A further limitation is that the authors were not blinded to the endline HbA1c or the treatment groups, and the study was not registered.

Despite its limitations, the study starts to provide an evidence base regarding the use of step count prescription in Nigerian general practice, as there has been no such study so far. A large proportion of health care in Nigeria is provided through general practice and primary healthcare centres. The use of a comparable control group also improves the strength of the study findings.

Comparison with existing literature

The attrition rate of 15.2% in the study is roughly comparable to the 20% noted by Tudor-Locke et al 17 over a 16-week pedometer-based intervention, and the 32% reported by Schneider et al 18 over a 32-week intervention. The majority of the participants (66.3%) in this current study achieved <5000 steps per day at baseline, and were therefore living a sedentary lifestyle according to the step-defined lifestyle index for adults.19 This supports other findings of low levels of physical activity among Nigerian adults, especially those with chronic illnesses.9,10,20,21

The 2913 steps per day (65%) higher step count in the intervention group in this study is much lower than similar studies on 10 000 steps per day walking prescription. A study by Swartz et al 22 in overweight inactive women recorded an 85% change in step count, while Schneider et al 18 reported a 3994 steps per day change in overweight and obese adults over 36 weeks. Likewise, Tudor-Locke et al 17 reported an increase of 3370 steps per day in overweight and obese individuals with T2DM. The low adherence rate of 6.1% in this study may suggest that achieving the 10 000 step goal was a difficult task in this population. This is much lower than the adherence rate of 33% reported by Schneider et al in a 10 000 steps per day intervention goal.18 There are, however, some difficulties in comparison with other studies because of varying definitions of adherence. The walking prescription was intended to give an easy-to-communicate and easy-to-follow prescription, compared with the frequency, duration, and intensity-based physical activity prescription.23 It encouraged individuals to achieve a specified number of walk steps per day, using a pedometer as an objective monitor of the accumulated steps. Since this 10 000 steps per day recommendation may be out of reach for sedentary individuals, a study has advocated incremental increases in steps per day as a viable starting point for sedentary individuals that may find it difficult to initially accumulate 10 000 steps per day.24

The 0.74% lower HbA1c in this study is close to the 0.50% decrease reported by Qiu et al 25 in a meta-analysis of studies that evaluated the association between walking and glycaemic control in individuals with T2DM, although none of these studies investigated a specific walking goal. Despite the small increase in step count and non-attainment of the 10 000 steps per day goal, there was still a significant reduction in the endline HbA1c and improved glycaemic control of participants in this study. This supports the argument of Katzmarzyk that incremental increases in physical activity that are below the recommended moderate level are still beneficial to health.26 This also gives credence to the physical activity recommendation which recognises that some physical activity is better than none.13 Individuals should, therefore, be encouraged to increase their physical activity or daily step count to levels they are comfortable with, and at least reap some health benefits, while they gradually progress to higher levels to reach recommended targets.27

Anthropometric and cardiovascular measurements did not change with the intervention, as was also reported by Tudor-Locke et al 17 and Rooney et al 28 with 10 000 step per day prescription. In contrast, Musto et al 24 reported a significant decrease in body weight, body mass index, and resting heart rate in a 12-week programme to increase daily steps. Likewise, Schneider et al 18 reported a significant improvement in body weight, body mass index, and waist circumference after 36 weeks. The low adherence and short duration of the present study might be a possible reason for the lack of these effects, which may be seen with better adherence and longer duration of intervention.

Implications for research and practice

This study is of significance to Nigerian general practice, which has hitherto given frequency, duration, and intensity-based physical activity prescriptions. Use of step-based, pedometer-monitored prescription may be an effective alternative. However, there is a need for further research on motivational strategies for prescription adherence.

Acknowledgments

Data analysis and writing of this paper were supported by the Medical Education Partnership Initiative in Nigeria (MEPIN).

Funding

None given.

Ethical approval

Oyo State Ministry of Health Research Ethical Review Committee (reference AD13/479/545).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.International Diabetes Federation . IDF diabetes atlas 5th edition. Brussels: IDF; 2011. The global burden. pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olokoba AB, Obateru OA, Olokoba LB. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review of current trends. Oman Med J. 2012;27(4):269–273. doi: 10.5001/omj.2012.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Diabetes Federation . IDF diabetes atlas 5th edition. Brussels: IDF; 2011. Regional overviews. pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes — 2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 1):S11–S66. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):e147–e167. doi: 10.2337/dc10-9990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Wasserman DH, Castaneda-Sceppa C. Physical activity/exercise and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(10):2518–2539. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Umpierre D, Ribeiro PB, Kramer CK, et al. Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305(17):1790–1799. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrato EH, Hill JO, Wyatt HR, et al. Physical activity in US adults with diabetes and at risk for developing diabetes, 2003. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(2):203–209. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adeniyi A, Idowu O, Ogwumike O, Adeniyi C. Comparative influence of self-efficacy, social support and perceived barriers on low physical activity development in patients with type 2 diabetes, hypertension or stroke. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2012;22(2):113–119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Idowu O, Adeniyi A, Atijosan O, Ogwumike O. Physical inactivity is associated with low self-efficacy and social support among patients with hypertension in Nigeria. Chronic Illn. 2013;9(2):156–164. doi: 10.1177/1742395312468012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oyewole O, Odusan O, Oritogun K, Idowu A. Physical activity among type 2 diabetic adult Nigerians. Ann Afr Med. 2014;13(4):189–194. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.142290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United States Department of Health and Human Services 2008 physical activity guidelines for Americans. 2008. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/downloads/pa_fact_sheet_adults.pdf (accessed 4 Dec 2017)

- 14.Schuna JM, Tudor-Locke C. Step by step: accumulated knowledge and future directions of step-defined ambulatory activity. Res Exerc Epidemiol. 2012;14(2):107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tudor-Locke C, Bassett DR., Jr How many steps/day are enough? Preliminary pedometer indices for public health. Sports Med. 2004;34(1):1–8. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shenoy S, Guglani R, Sandhu JS. Effectiveness of an aerobic walking program using heart rate monitor and pedometer on the parameters of diabetes control in Asian Indians with type 2 diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(1):41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tudor-Locke C, Bell RC, Myers AM, et al. Controlled outcome evaluation of the First Step Program: a daily physical activity intervention for individuals with type II diabetes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(1):113–119. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider PL, Bassett DR, Jr, Thompson DL, et al. Effects of a 10 000 steps per day goal in overweight adults. Am J Health Promot. 2006;21(2):85–89. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tudor-Locke C, Craig CL, Thyfault JP, Spence JC. A step-defined sedentary lifestyle index: <5000 steps/day. App Phys Nutr Met. 2012;38(2):100–114. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2012-0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adegoke BO, Oyeyemi AL. Physical inactivity in Nigerian young adults: prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(8):1135–1142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adeniyi A, Ogwumike O, John-Chu C, et al. Links among motivation, sociodemographic characteristics and low physical activity level among a group of Nigerian patients with type 2 diabetes. J Med Biomed Sci. 2013;2(3):8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swartz AM, Strath SJ, Bassett DR, et al. Increasing daily walking improves glucose tolerance in overweight women. Prev Med. 2003;37(4):356–362. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tudor-Locke C, Craig CL, Brown WJ, et al. How many steps/day are enough? For adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:79. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Musto A, Jacobs K, Nash M, et al. The effects of an incremental approach to 10 000 steps/day on metabolic syndrome components in sedentary overweight women. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(6):737–745. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu S, Cai X, Schumann U, et al. Impact of walking on glycemic control and other cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katzmarzyk PT. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and health: paradigm paralysis or paradigm shift? Diabetes. 2010;59(11):2717–2725. doi: 10.2337/db10-0822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Wasserman DH, et al. Physical activity/exercise and type 2 diabetes: a consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(6):1433–1438. doi: 10.2337/dc06-9910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rooney BL, Gritt LR, Havens SJ, et al. Growing healthy families: family use of pedometers to increase physical activity and slow the rate of obesity. WMJ. 2005;104(5):54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]