Preconditioning refers to a diverse group of biologic phenomena in which myocardial tissue is rendered ischemic for a short, non-lethal period, and subsequently exhibits reduced injury in response to ischemia.1 This phenomenon, first discovered over 30 years ago2, has become a major subject of laboratory research. Myocardial preconditioning can be induced with short periods of coronary occlusion known as ischemic preconditioning or by rendering a distant tissue ischemic, such as with an arm tourniquet, known as remote ischemic preconditioning. Preconditioning can also be induced pharmacologically by certain agents3 whereas others are known to interfere with preconditioning.4–6 A wealth of cellular mechanisms have been discovered that contribute to the development of preconditioning including changes in phosphoinositol-3, protein kinase C, reactive oxygen species, electron transport chain complex III, nitric oxide synthases, KATP channels, and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore.

Remote ischemic preconditioning is a reproducible phenomenon that has been observed and extensively studied in multiple species.7,8 In laboratory models, remote ischemic preconditioning can reliably decrease myocardial infarct size by 20–50%. Despite the ongoing interest in using remote ischemic preconditioning in cardiac surgery based on extensive animal data, only a small number of clinical trials have produced promising results.9–13 These preliminary trials prompted two large randomized clinical trials of remote ischemic preconditioning in cardiac surgical patients, RIPHeart and ERICCA, that were both completed in 2015 but to the disappointment of many, both trials were negative reporting no beneficial effect of remote ischemic preconditioning.14,15. How could such a robust laboratory effect be ineffective in a clinical trial?

Ischemic preconditioning is most commonly shown in laboratory models of ischemia-reperfusion where animals are anesthetized, usually with barbiturates, anesthetics which only weakly induce pharmacologic preconditioning in laboratory animals.16,17 In the cardiac operating room, patients are given a balanced anesthetic consisting of drugs known to more potently induce preconditioning such as volatile anesthetics and opioids, either of which may eclipse the protective effect of ischemic preconditioning by providing more robust pharmacologic preconditioning.18–22 Many of these drugs induce changes in gene and protein expression that are remarkably similar to those changes wrought by ischemic preconditioning.23,24 This knowledge led RIPHeart investigators to make the use of volatile anesthetics in patients enrolled in their study an exclusion criteria. Additionally, patients undergoing cardiac surgery may receive post-operative sedation, analgesics, beta-blockade, statins, and antifibrinolytic drugs, some of which are known to induce or interfere with preconditioning. As a large number of drugs have been noted in the laboratory to induce or modify preconditioning we have included Table 1 highlight some of the commonly used drugs that alter myocardial protection. While no large prospective randomized trials exist that clearly demonstrate a benefit to pharmacologic preconditioning two meta-analyses show a clinical benefit to cardiac anesthesia that incorporates volatile anesthetic known to induce preconditioning.19,20 Additionally, a review of Danish registry data showed a clinical benefit of exposure to volatile anesthetics in patients that did not experience preceding ischemia, reported as angina.21 Taken together these studies suggest that preconditioning can be induced by non-lethal ischemia, a host of pharmacologic agents, and can be enhanced or inhibited by a number of other drugs, however, it seems that pharmacologic preconditioning cannot be superimposed on ischemic preconditioning or vice versa. That brings us to the current study in the Journal of the carefully conducted experiments by van Caster et al25, which have endeavored to clarify the role of the antifibrinolytic drug, tranexamic acid (TXA), in ischemic preconditioning and remote ischemic preconditioning.

Table 1.

| Physiologic and Pharmacologic Inducers of Preconditioning | Agents Known to Inhibit Preconditioning |

|---|---|

|

Non-Lethal Periods of Ischemia Direct Ischemic Preconditioning1 Remote Ischemic Preconditioning3 |

Adenosine Receptor Antagonists (Methylxanthines) Theophylline, Aminophylline2 Caffeine2 |

|

Receptor and Plasma Membrane Interactions Volatile Anesthetics4 Lidocaine5 Adenosine and Adenosine Agonists5 Opioids6 |

KATP Channel Inhibitors (Sulfonylureas) Glipizide2 Glyburide2 |

|

Anti-Fibrinolytic Drugs Aprotonin7 | |

|

Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors Sildenafil8 |

eNOS/iNOS inhibitors L-NAME9 |

|

Beta-Blockers Propranolol10 Nipradolol10 |

Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation 1986;74:1124–36.

Gumina RJ, Beier N, Schelling P, Gross GJ. Inhibitors of ischemic preconditioning do not attenuate Na+/H+ exchange inhibitor mediated cardioprotection. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology 2000;35:949–53.

Zimmerman RF, Ezeanuna PU, Kane JC, et al. Ischemic preconditioning at a remote site prevents acute kidney injury in patients following cardiac surgery. Kidney international 2011;80:861–7.

Zaugg M, Lucchinetti E, Spahn DR, Pasch T, Schaub MC. Volatile anesthetics mimic cardiac preconditioning by priming the activation of mitochondrial K(ATP) channels via multiple signaling pathways. Anesthesiology 2002;97:4–14.

Canyon SJ, Dobson GP. Pretreatment with an adenosine A1 receptor agonist and lidocaine: a possible alternative to myocardial ischemic preconditioning. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery 2005;130:371–7.

Gross GJ. Role of opioids in acute and delayed preconditioning. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology 2003;35:709–18.

Fradorf J, Huhn R, Weber NC, et al. Sevoflurane-induced preconditioning: impact of protocol and aprotinin administration on infarct size and endothelial nitric-oxide synthase phosphorylation in the rat heart in vivo. Anesthesiology 2010;113:1289–98.

Kukreja RC, Salloum F, Das A, et al. Pharmacological preconditioning with sildenafil: Basic mechanisms and clinical implications. Vascular pharmacology 2005;42:219–32.

Lochner A, Marais E, Du Toit E, Moolman J. Nitric oxide triggers classic ischemic preconditioning. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2002;962:402–14.

Suematsu Y, Anttila V, Takamoto S, del Nido P. Cardioprotection afforded by ischemic preconditioning interferes with chronic beta-blocker treatment. Scandinavian cardiovascular journal : SCJ 2004;38:293–9.

There is a substantial precedent for the hypothesis that antifibrinolytic agents could interfere with remote ischemic preconditioning. Antifibrinolytic drugs are serine protease inhibitors that inhibit fibrinolysis, the cleavage of cross-linked fibrin by plasmin. This process, when uncontrolled, can deplete coagulation factors and lead to coagulopathy. Antifibrinolytics also have other indirect effects; by inhibiting the activity of plasmin, they can be anti-inflammatory. Plasmin, particularly when bound to the surface of macrophages, plays a critical role in monocyte activation and inflammation including activation of the complement cascade, exit from circulation into injured or infected tissue, cytokine production, and proteolytic activation of matrix-metalloproteases (MMP) with subsequent degradation and remodeling of extra-cellular matrix (ECM). Activated plasmin elicits chemotaxis and actin polymerization in monocytes including the release of cytokines downstream of the NF-κB, AP-1, and STAT transcription factors.26,27 In cardiac surgery, TXA and aprotinin were studied using whole blood mRNA expression profiling of inflammatory genes. Of the 114 genes studied, eight produced less mRNA in the presence of aprotinin, while three genes were inhibited by TXA and aprotinin, the broader spectrum of aprotinin most likely owing to its broader inhibitory activity against serine proteases.28 Antifibrinolytic use in clinical settings has anti-inflammatory effects,29 and thus the potential to provide protection during ischemic insults. Several studies report that aprotinin is protective during ischemia.30 While the anti-inflammatory effect of antifibrinolytics might enhance myocardial preconditioning protecting heart tissue, there is also significant data suggesting that antifibrinolytics may impair preconditioning as reported in the current study in this journal by Van Caster et al.25

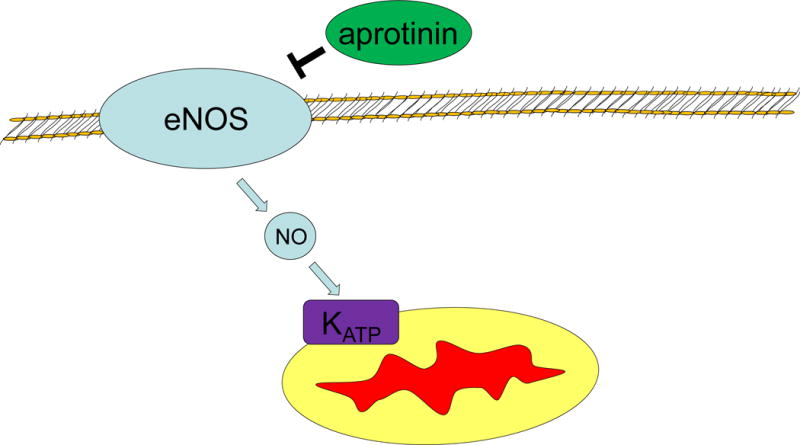

In a series of carefully controlled animal experiments, Frässdorf et al demonstrated significant and reproducible inhibition of pharmacologic preconditioning by aprotinin.5 In a rat model of ischemia reperfusion aprotinin was able to eliminate the protective effects of sevoflurane preconditioning resulting in larger sized myocardial infarction. This was associated with a significant reduction in nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation, and has also been the subject of review.6 Figure 1 demonstrates aprotonin’s inhibitory action on nitric oxide dependent preconditioning. This and other works31,32 have identified antifibrinolytic drugs as a potential inhibitor of preconditioning. Could the routine use of antifibrinolytic drugs be the reason why the large trials of remote ischemic preconditioning were negative? Preconditioning clinical trials to date have allowed for clinician usual practice in anesthetics and perioperative pharmacotherapy, making the rate of antifibrinolytic use unclear. Few studies have been conducted to examine the effect of antifibrinolytic drugs on preconditioning or remote ischemic preconditioning.

Figure 1. Aprotonin inhibits endothelial nitric oxide synthase.

eNOS – Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase

NO – Nitric Oxide

KATP- Mitochondrial ATP dependent potassium channel

Although the study by Van Caster et al25 in this journal is a negative study, it demonstrates a critical finding. TXA does not have an inhibitory effect on ischemic preconditioning or remote ischemic preconditioning in rats. This finding highlights the fact that small differences in TXA and aprotinin’s activity, result in large differences in regard to its effects on ischemia reperfusion. While aprotinin potently blocks preconditioning, TXA seems to exert no effect on preconditioning. While this is not the same as a large trial in humans, it highlights a critical difference between TXA and aprotinin. While both molecules interact with the lysine binding site on plasmin, TXA is relatively specific for this while aprotinin retains broader inhibitory activity against multiple serine proteases. Aprotinin’s broader inhibition of proteolytic activity including inhibition of PAR1 receptors is most-likely responsible for its blockade of the cascade of reactions that lead to preconditioning, pharmacologic preconditioning, and remote ischemic preconditioning.33 TXA’s specificity means that, in humans, it may not disturb preconditioning or remote ischemic preconditioning while it remains effective as an antifibrinolytic drug.34

The work of van Caster et al provides additional information on the behavior of TXA in an animal model of preconditioning. This is key, as it may help us understand the interplay of the complex mix of drugs employed during a typical cardiac anesthetic. Given this complex interplay, it is possible that the reason two large randomized trials of remote ischemic preconditioning14,15 are negative has to do with a drug or drugs administered during surgery which could inhibit preconditioning, such as aprotinin. Alternatively, the mix of drugs given during a typical anesthetic could induce pharmacologic preconditioning so potently, that remote ischemic preconditioning has no further protection to give. While neither RIPHeart or ERICCA specifically mention antifibrinolytic use in their study protocol, animal data suggests that there may be significant differences in the behavior of antifibrinolytics as they relate to preconditioning. The increased specificity of TXA compared with aprotonin may mean that it can function effectively as an antifibrinolytic without inhibiting the protection granted by preconditioning, remote ischemic preconditioning, and pharmacologic preconditioning, at least in rats.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources:

NIGMS T32 GM08600, Duke University Medical Center, Fellow: Quintin Quinones

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

None - QJQ

None - JHL

Editorial in reference to: “Tranexamic acid does not influence cardioprotection by ischemic preconditioning and remote ischemic preconditioning” (MS # AAD-16-00916R2)

Quintin J. Quinones: wrote the first draft of the manuscript and revised the subsequent versions.

Jerrold H. Levy : reviewed and edited the first draft of the manuscript and edited additional revisions.

References

- 1.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Ischaemic conditioning and reperfusion injury. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2016;13:193–209. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:1124–36. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riess ML, Stowe DF, Warltier DC. Cardiac pharmacological preconditioning with volatile anesthetics: from bench to bedside? American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2004;286:H1603–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00963.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meier JJ, Gallwitz B, Schmidt WE, Mugge A, Nauck MA. Is impairment of ischaemic preconditioning by sulfonylurea drugs clinically important? Heart. 2004;90:9–12. doi: 10.1136/heart.90.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fradorf J, Huhn R, Weber NC, et al. Sevoflurane-induced preconditioning: impact of protocol and aprotinin administration on infarct size and endothelial nitric-oxide synthase phosphorylation in the rat heart in vivo. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:1289–98. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f97fec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frassdorf J, De Hert S, Schlack W. Anaesthesia and myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury. British journal of anaesthesia. 2009;103:89–98. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Kloner RA. Cardioprotective effects of ischemic preconditioning can be recaptured after they are lost. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1994;23:470–4. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90435-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schott RJ, Rohmann S, Braun ER, Schaper W. Ischemic preconditioning reduces infarct size in swine myocardium. Circulation research. 1990;66:1133–42. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.4.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimmerman RF, Ezeanuna PU, Kane JC, et al. Ischemic preconditioning at a remote site prevents acute kidney injury in patients following cardiac surgery. Kidney international. 2011;80:861–7. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meybohm P, Renner J, Broch O, et al. Postoperative neurocognitive dysfunction in patients undergoing cardiac surgery after remote ischemic preconditioning: a double-blind randomized controlled pilot study. PloS one. 2013;8:e64743. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joung KW, Rhim JH, Chin JH, et al. Effect of remote ischemic preconditioning on cognitive function after off-pump coronary artery bypass graft: a pilot study. Korean journal of anesthesiology. 2013;65:418–24. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2013.65.5.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venugopal V, Laing CM, Ludman A, Yellon DM, Hausenloy D. Effect of remote ischemic preconditioning on acute kidney injury in nondiabetic patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a secondary analysis of 2 small randomized trials. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2010;56:1043–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krogstad LE, Slagsvold KH, Wahba A. Remote ischemic preconditioning and incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation. Scandinavian cardiovascular journal : SCJ. 2015;49:117–22. doi: 10.3109/14017431.2015.1010565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meybohm P, Bein B, Brosteanu O, et al. A Multicenter Trial of Remote Ischemic Preconditioning for Heart Surgery. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373:1397–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1413579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hausenloy DJ, Candilio L, Evans R, et al. Remote Ischemic Preconditioning and Outcomes of Cardiac Surgery. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373:1408–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1413534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller DL, Van Winkle DM. Ischemic preconditioning limits infarct size following regional ischemia-reperfusion in in situ mouse hearts. Cardiovascular research. 1999;42:680–4. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cope DK, Impastato WK, Cohen MV, Downey JM. Volatile anesthetics protect the ischemic rabbit myocardium from infarction. Anesthesiology. 1997;86:699–709. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199703000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kersten JR, Schmeling TJ, Pagel PS, Gross GJ, Warltier DC. Isoflurane mimics ischemic preconditioning via activation of K(ATP) channels: reduction of myocardial infarct size with an acute memory phase. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:361–70. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199708000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Symons JA, Myles PS. Myocardial protection with volatile anaesthetic agents during coronary artery bypass surgery: a meta-analysis. British journal of anaesthesia. 2006;97:127–36. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu CH, Beattie WS. The effects of volatile anesthetics on cardiac ischemic complications and mortality in CABG: a meta-analysis. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d’anesthesie. 2006;53:906–18. doi: 10.1007/BF03022834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jakobsen CJ, Berg H, Hindsholm KB, Faddy N, Sloth E. The influence of propofol versus sevoflurane anesthesia on outcome in 10,535 cardiac surgical procedures. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2007;21:664–71. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludwig LM, Patel HH, Gross GJ, Kersten JR, Pagel PS, Warltier DC. Morphine enhances pharmacological preconditioning by isoflurane: role of mitochondrial K(ATP) channels and opioid receptors. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:705–11. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200303000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sergeev P, da Silva R, Lucchinetti E, et al. Trigger-dependent gene expression profiles in cardiac preconditioning: evidence for distinct genetic programs in ischemic and anesthetic preconditioning. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:474–88. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200403000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalenka A, Maurer MH, Feldmann RE, Kuschinsky W, Waschke KF. Volatile anesthetics evoke prolonged changes in the proteome of the left ventricule myocardium: defining a molecular basis of cardioprotection? Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2006;50:414–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Caster ES, Boekholt Y, Behmenburg F, Dorsch M, Heinen A, Hollmann MW, Huhn R. Tranexamic Acid Does Not Influence Cardioprotection by Ischemic Preconditioning and Remote Ischemic Preconditioning. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2017 doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Syrovets T, Jendrach M, Rohwedder A, Schule A, Simmet T. Plasmin-induced expression of cytokines and tissue factor in human monocytes involves AP-1 and IKKbeta-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Blood. 2001;97:3941–50. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.12.3941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burysek L, Syrovets T, Simmet T. The serine protease plasmin triggers expression of MCP-1 and CD40 in human primary monocytes via activation of p38 MAPK and janus kinase (JAK)/STAT signaling pathways. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:33509–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Later AF, Sitniakowsky LS, van Hilten JA, et al. Antifibrinolytics attenuate inflammatory gene expression after cardiac surgery. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2013;145:1611–6. 6e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy JH. Antifibrinolytic therapy: new data and new concepts. Lancet. 2010;376:3–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60939-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan TA, Bianchi C, Voisine P, et al. Reduction of myocardial reperfusion injury by aprotinin after regional ischemia and cardioplegic arrest. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2004;128:602–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bukhari EA, Krukenkamp IB, Burns PG, et al. Does aprotinin increase the myocardial damage in the setting of ischemia and preconditioning? The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1995;60:307–10. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cosgrove DM, 3rd, Heric B, Lytle BW, et al. Aprotinin therapy for reoperative myocardial revascularization: a placebo-controlled study. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1992;54:1031–6. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)90066-d. discussion 6-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mojcik CF, Levy JH. Aprotinin and the systemic inflammatory response after cardiopulmonary bypass. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2001;71:745–54. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts I, Shakur H, Coats T, et al. The CRASH-2 trial: a randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of the effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events and transfusion requirement in bleeding trauma patients. Health technology assessment. 2013;17:1–79. doi: 10.3310/hta17100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]