Abstract

Background/Goals

Inpatient colonoscopy preparations are often inadequate, compromising patient safety and procedure quality, while resulting in greater hospital costs. The aims of this study were to 1) Design and implement an electronic inpatient split-dose bowel preparation order set; 2) Assess the intervention’s impact upon preparation adequacy, repeated colonoscopies, hospital days, and costs.

Study

We conducted a single center prospective pragmatic quasi-experimental study of hospitalized adults undergoing colonoscopy. The experimental intervention was designed using DMAIC methodology. Prospective data collected over 12 months was compared to data from a historical pre-intervention cohort. The primary outcome was bowel preparation quality and secondary outcomes included number of repeated procedures, hospital days and costs.

Results

Based on a Delphi method and DMAIC process, we created an electronic inpatient bowel preparation order set inclusive of a split dose bowel preparation algorithm, automated orders for rescue medications and nursing bowel preparation checks. The analysis dataset included 969 patients, 445 (46%) in the post-intervention group. The adequacy of bowel preparation significantly increased following intervention (86% vs. 43%, p<0.01) and proportion of repeated procedures decreased (2.0% vs. 4.6%, p=0.03). Mean hospital days from bowel preparation initiation to discharge decreased from 8.0 to 6.9 days (p=0.02). The intervention resulted in an estimated one-year cost-savings of $46,076 based on a reduction in excess hospital days associated with repeated and delayed procedures.

Conclusions

Our interdisciplinary initiative targeting inpatient colonoscopy preparations significantly improved quality and reduced repeat procedures, and hospital days. Other institutions should consider utilizing this framework to improve inpatient colonoscopy value.

Keywords: Colonoscopy quality, Quality Improvement, DMAIC methodology

Introduction

Achieving adequate bowel preparation quality is integral to ensuring an optimal diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopy in the inpatient setting. However, nearly half of inpatient colonoscopy preparations are suboptimal.(1–8) Inadequate bowel preparations are associated with procedure delays, need for repeat procedures, longer hospital length of stay and higher hospital costs.(3) As a large number of colonoscopies are performed in the United States, an estimated 11.5 million in 2009, inadequate preparations represent a significant source of wasted healthcare dollars and may potentially lead to adverse outcomes. (9)

Inpatient colonoscopies performed in the afternoon are associated with inadequate bowel preparations.(3) This risk is potentially attributed to longer preparation-to-colonoscopy time intervals, and is a potentially modifiable risk factor. In the ambulatory setting, split-dose bowel preparations are superior to single dose preparations; however, split-dosing is perceived as cumbersome to administer in the inpatient setting without proven efficacy in the literature.(10–13) Consequently, split-dose preparations are not widely used amongst hospitalized patients.

The aims of this study were to 1) Design and implement an electronic inpatient split-dose bowel preparation order set; and 2) Assess the intervention’s impact upon preparation adequacy, repeated colonoscopies, hospital days, and costs.

Materials and Methods

We performed a prospective pragmatic non-randomized quasi-experimental study at an academic medical center over an 18-month period (January 1, 2014 to June 30, 2015), designing and assessing the impact of an inpatient bowel preparation improvement initiative. The Northwestern University institutional review board (protocol number STU00089524) approved this study and granted a waiver of informed consent.

Study Design

Intervention Development

Over a six-month period (1/1/2014 to 6/30/2014), our study team utilized DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control) methodology to design an inpatient electronic bowel preparation algorithm. DMAIC is a data-driven improvement cycle to improve, optimize and stabilize processes. (15) The interdisciplinary team consisted of a project lead (RY), project champion/principal investigator (RNK), unit nurse, nursing educator (LW), patient educator, gastroenterology (GI) trainee, internal medicine trainee (ERJ), hospital medicine physician (RC), pharmacist, and information technology specialist. To formulate an evidence and consensus based split-dose bowel preparation algorithm, we conducted a two-round Delphi method with a working group of eight inpatient GI attendings. (16) We incorporated the bowel preparation algorithm into an electronic order set. Implementation: The team fully implemented the inpatient bowel preparation order set on 7/1/2014, and prospectively collected data over the subsequent 12-month period (7/1/2014 to 6/31/2015).

Study Population

We compared data between two cohorts, the post-intervention cohort and the historical pre-intervention cohort. Post-intervention cohort: We prospectively enrolled all adult patients scheduled to undergo inpatient colonoscopy over a 12-month period (July 1, 2014 to June 30, 2015). Pre-intervention cohort: In order to assess the intervention’s impacts, we retrospectively collected data on a cohort of patients who received single dose 4 liters of GoLytely the evening prior to inpatient colonoscopy over a 12-month period prior to interventions (1/1/2013 to 12/31/2013). We identified these patients through a query of our endoscopy documentation system, ProVation Medical (Minneapolis, MN). Both cohorts included all hospitalized patients who received a bowel preparation and underwent an inpatient colonoscopy regardless of prior surgical history or procedural indication; patients not scheduled to receive a bowel preparation and those planning to undergo a sigmoidoscopy were excluded.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was bowel preparation quality. The secondary outcomes included rates of delayed and repeated (inpatient or within 3 months as an outpatient) procedures due to inadequate preparation, hospital days from time of preparation initiation to discharge, and hospital costs.

We extracted the quality of bowel preparation from the colonoscopy procedure report. Through a structured chart review of all identified patients for study inclusion, the study team gathered patient demographics, comorbidities, presence of gastrointestinal symptoms, colonoscopy history, medication use, and hospital days. In order to calculate average cost per day, we extracted available cost data for all patients from the Northwestern Medical Enterprise Data Warehouse, an integrated repository of clinical and research data sources.

Rater Reliability & Agreement for Primary Outcome

Since two different scales were used to rank bowel preparations in the two cohorts (the Aronchick scale was used to rank the majority of bowel preparations in the pre-intervention cohort and the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) was utilized in the post-intervention cohort) we conducted an analysis to assess inter- and intra-observer agreement for bowel preparations. Thirteen GI fellows viewed 10 video clips, each representing the right, transverse, and left colon segments, and ranked them according to the Aronchick scale, provided segmental BBPS scores, and indicated overall preparation adequacy. From 650 total observations, there was a strong significant correlation between Aronchick and BBPS rankings (Spearman r=0.85, p <0.01), and intra-observer agreement was excellent between Aronchick and BBPS (ĸ 0.89, 95% CI 0.82–0.97), BBPS and overall adequacy (ĸ 0.86, CI 0.77–0.95), and Aronchick and overall adequacy (ĸ 0.82, CI 0.72–0.91). Inter-observer agreement was very high for the Aronchick scale (94%), BBPS (92%), and overall adequacy (92%).

Definitions

A priori, we classified bowel preparation quality dichotomously as adequate or inadequate. We defined a preparation as inadequate if described as “poor” on the Aronchick scale, had a total BBPS < 6 or segmental BBPS < 2, and/or, when the colonoscopy was delayed for at least one hospital day due to poor preparation.(17, 18) Conversely, we defined a bowel preparation as adequate if the record indicated “adequate”, “good”, or “excellent”, a total BBPS ≥ 6 or segmental BBPS ≥ 2. While a “fair” preparation according to the Aronchick scale is considered to be adequate(17), the majority (60%) of our endoscopists considered “fair” to be inadequate during a provider survey and in our agreement analysis fellows considered 58% of “fair” cases to be inadequate. Similarly, recent expert opinion supports that preparations described as “fair” lack meaning and a prior study validating the BBPS associated “fair” preparations with a mean BBPS of 5.(19, 20) Thus, we a priori considered “fair” to be inadequate in primary analysis, and conducted a separate sensitivity analysis considering “fair” as adequate [Table 1].

Table 1.

Primary Outcome Definitions

| Bowel Preparation Quality | Definition |

|---|---|

| Adequate | Total BBPS ≥ 6; Segmental BBPS ≥ 2; Preparation description of “Adequate”, “Good”, “Excellent”; And/or no delay in colonoscopy due to inadequate preparation |

|

| |

| Inadequate | Total BBPS < 6; Segmental BBPS < 2; Preparation description of “Poor”, “Fair”*; And/or delay in colonoscopy of at least one day due to inadequate preparation |

We, a priori, defined “Fair” preparations as inadequate based on available literature and provider survey. Given conflicting opinions and literature on the adequacy of a “Fair” preparation, we conducted a secondary analysis considering “Fair” as adequate.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses evaluated differences in pre-identified risk factors and outcomes between the pre-intervention and post-intervention groups. An independent two-sample t-test examined mean age across the two groups, while the Cochrane-Mantel-Haenszel test controlling for American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class explored dichotomous risk factors and the proportions of patients with inadequate preparation, delayed colonoscopy and repeated colonoscopy. Analyses for hospital days employed truncated negative binomial regression controlling for ASA class, as this covariate was highly significantly associated with hospital days. Overall cost savings was figured by multiplying the mean cost by the average number of days that length of stay was increased by a repeated or delayed colonoscopy due to inadequate bowel preparation, and then by the estimated number of patients in the prospective group who were prevented from having a repeated or delayed colonoscopy. All statistical analyses and figure generation utilized SAS software, Version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Development of Inpatient Electronic Bowel Preparation Algorithm

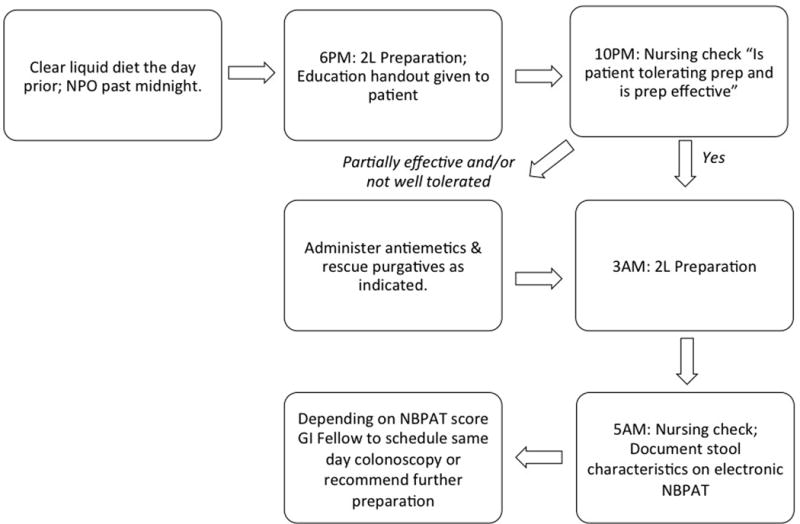

Based on consensus from the two-round Delphi process the inpatient bowel preparation algorithm included split-dose NuLytely® (Braintree Laboratories Inc., Braintree, MA) with 2 Liters administered at 6PM and 2 Liters administered at 3AM. Additionally, the algorithm incorporated two nursing checkpoints to assess preparation efficacy: four hours after preparation initiation and two hours after administration of the second dose [Figure 1]. If the preparation was poorly tolerated or ineffective, then the electronic order set prompted nurses to administer rescue or alternative purgative agents. In order to allow for standardized documentation during nursing assessment of the preparation process, we created an electronic nursing bowel preparation assessment tool (NBPAT). The NBPAT is an internally validated tool used to assess three bowel preparation characteristics: color, consistency, and sediment. Based on responses to each, an overall NBPAT score (ranging from 0–5) is automatically summated [Figure 2]. (21) This NBPAT score is electronically recorded and immediately available to the health care team via the electronic health record. To ensure consistency of orders, we created a standardized electronic order set including the above interventions and incorporated it into the electronic health record [Figure 3].

Figure 1. Standardized Bowel Preparation Algorithm.

The study team developed this bowel preparation algorithm via a two-round Delphi method with eight gastroenterology attendings. The new algorithm incorporates a split-dose bowel preparation to start at 6PM the evening prior to scheduled procedure. If at the 10PM nursing check the preparation is well tolerated and effective, the next step is to administer the second portion of the split-dose preparation at 3AM. If, however, at the 10PM nursing check the patient is not tolerating the preparation or the preparation is ineffective, nurses are advised to additionally administer antiemetics (Ondansetron) and rescue purgatives as appropriate (Bisacodyl, Magnesium Citrate [not to be used if CrCl < 30 mL/min], and/or tap water enemas). During the second nursing check at 5AM nurse documents the prepped stool characteristics on the electronic nursing bowel preparation assessment tool (NBPAT). This documentation is immediately available on the electronic health record. The gastroenterology fellow checks the NBPAT documentation in the morning to gauge pre-procedural preparation adequacy and proceeds accordingly.

Figure 2. The Nursing Bowel Preparation Assessment Tool (NBPAT).

Prepared stool is scored based on three sub-groups: consistency (solid=0, semi-solid=1, liquid=2), color (brown=0, orange/dark yellow=1, clear/light yellow=2), sediment (present=0, not present=1). A total bowel preparation score out of 5, with 5 being most optimal, is automatically summated. This tool is documented and available to the healthcare team immediately via the electronic health record. Image embedded in the figure borrowed with permission from Dr. Brennan Spiegel.

Figure 3. The Electronic Colonoscopy Order Set.

Improvement interventions incorporated into a single electronic colonoscopy order set and include automated nursing instructions on split-dose bowel preparation administration, preparation checks, and use of rescue agents as needed.

Outcomes Following Implementation

We implemented the electronic inpatient split dose bowel preparation order set on July 1, 2014. Over the subsequent 12-month period, 445 patients met study inclusion criteria, and were compared to 524 patients undergoing inpatient colonoscopy prior to intervention. Of all 969 patients included in this study, the mean age was 57.7±17.1 years and 46.9% (455) were female. There were no significant demographic differences between the pre-intervention and post-intervention cohort. A greater proportion of the pre-intervention cohort had an ASA ≥3 (40.7% vs 27.7%, p<0.01) and thus all analyses controlled for potential confounding effects of ASA. The most common indication for inpatient colonoscopy was gastrointestinal bleeding (40.3% in pre-intervention cohort and 36.3% in the post-intervention cohort) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Baseline clinical variables for pre- and post-intervention groups.

| Variable | Pre-intervention Group (n = 524) |

Post-intervention Group (n =445) |

Unadjusted P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (years) | 57.1 ± 17.8 | 58.2 ± 16.6 | 0.34 |

|

| |||

| Gender (female) | 255 (48.7%) | 200 (44.9%) | 0.25 |

|

| |||

| ASA ≥ 3 | 213 (40.7%) | 123 (27.7%) | <0.01 |

|

| |||

| Cirrhosis | 71 (13.7%) | 52 (11.7%) | 0.36 |

|

| |||

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 39 (7.5%) | 32 (7.3%) | 0.89 |

|

| |||

| Afternoon colonoscopies | 205 (39.2%) | 189 (42.6%) | 0.97 |

|

| |||

| Opiates and/or Tricyclic Antidepressants | 176 (33.6%) | 174 (39.4%) | 0.06 |

|

| |||

| Procedure Indication* | |||

| GI Bleeding | 207 (40.3%) | 159 (36.3%) | |

| Iron Deficiency Anemia | 73 (14.2%) | 69 (15.8%) | |

| Diarrhea | 89 (17.3%) | 71 (16.2%) | |

| Abdominal pain | 27 (5.3%) | 17 (3.9%) | |

| Abnormal imaging | 30 (5.8%) | 24 (5.5%) | |

| Other | 88 (17.1%) | 98 (22.4%) | |

Statistical significance was determined via independent two-sample t-test for mean age. % across the two groups and the Cochrane-Mantel-Haenszel test controlling for ASA class for dichotomous risk factors.

Indication data missing for 17 subjects. Procedure indication between pre- and post-intervention cohorts with an overall p-value of 0.3.

Following implementation of the inpatient bowel preparation intervention, we found a significant improvement in preparation quality with adequacy increasing from 42.5% pre-intervention to 85.7% post-intervention (p<0.01). Improvement in preparation quality persisted over the 12-month study period, with monthly preparation adequacy rates ranging from 72.0% to 95.0%. There was 93.3% compliance with utilizing the electronic colonoscopy order. As expected, following the intervention, significantly more patients received a split-dose preparation (91.5% vs. 1.3%, p<0.01) and additional “rescue” purgatives prior to colonoscopy (25.0% vs. 4.2%, p<0.01). Furthermore, documentation of BBPS significantly increased following intervention (84.7% vs. 0.5%, p <0.01). In a sensitivity analysis considering “fair” preparations as adequate, a significant increase in bowel preparation adequacy persisted post-intervention (85.7% vs 77.8%, p<0.01) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of primary and secondary outcomes between pre- and post-intervention groups, controlling for ASA group.

| Pre-intervention Group (n = 524) | Post-intervention Group (n = 445) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate bowel preparations | 223 (42.5%) | 381 (85.7%) | <0.01 |

| Adequate bowel preparations if “fair” included as “Adequate” | 407 (77.8%) | 381 (85.7%) | <0.01 |

| Repeated inpatient colonoscopies due to an inadequate preparation | 22 (4.2%) | 9 (2.0%) | 0.06 |

| Repeated colonoscopies (inpatient or outpatient within 3 months) due to an inadequate preparation | 24 (4.6%) | 9 (2.0%) | 0.03 |

| Delayed inpatient colonoscopies due to an inadequate preparation | 34 (6.5%) | 33 (7.4%) | 0.57 |

| Hospital days following preparation initiation to time of discharge* | 8.0 ± 11.4 | 6.9 ± 8.8 | 0.02 |

Statistical significance was determined via the Cochrane-Mantel-Haenszel test controlling for ASA class.

Hospital length of stay analyzed through truncated negative binomial regression controlling for ASA class, as this covariate was significantly associated with hospital days.

We observed a significant decrease in the proportion of colonoscopies repeated as an inpatient or outpatient (within 3 months) due to prior inadequate inpatient bowel preparation (2.0% vs. 4.6%, p=0.03). Furthermore, there was a significant decrease in mean hospital days from bowel preparation initiation to time of discharge in the post-intervention cohort (6.9 days vs. 8.0 days, p=0.02). However, the proportion of procedures delayed due to inadequate preparation did not decrease post-intervention (7.4% vs. 6.5%, p=0.6). Based on a reduction in excess hospitalization days due to repeat and delayed procedures, we estimated a one-year cost savings of $46,076 attributed to the intervention (not accounting for the costs of the additional inpatient or outpatient colonoscopy procedures).

Conclusions

Here we report the outcomes of a pragmatic quasi-experimental study to improve the quality of inpatient bowel preparations at our institution. This initiative implemented an electronic inpatient bowel preparation order set consisting of a standardized split-dose bowel preparation algorithm with automated orders for rescue medication administration and nursing bowel preparation assessments. Following implementation, the rate of adequate bowel preparations significantly increased (from 43% to 86%) with a commensurate decrease in repeated procedures and hospital days from time of bowel preparation to discharge.

Our healthcare system has shifted towards emphasizing value, with a primary focus on optimizing the quality of patient care while reducing costs. Accomplishing these goals requires efforts to eliminate repeat procedures and delays in patient care that lead to unnecessary healthcare expenditure in the inpatient setting.(22),(23) Optimizing the value of inpatient colonoscopy is critical to improving patient care and reducing healthcare costs. In this study, we utilized a systematic approach to successfully reengineer and standardize the clinical and administrative processes associated with inpatient bowel preparation practices. Our results illustrate that this is a modifiable problem with clinically feasible and sustainable solutions with potential to improve outcomes and reduce costs. The significantly high compliance with the colonoscopy order set and administration of split-dose preparation and rescue purgatives following intervention additionally highlight the ease with which the order-set was incorporated into routine clinical workflow. Thus, practice patterns can be modified via structured clinical aids, even for practices perceived as burdensome such as inpatient split-dosing. Consolidating the improvement ideas into a single standardized electronic colonoscopy order set was additionally useful in reducing the complexity of workflow changes, decreasing variability and automating communication amongst the healthcare team.

Unexpectedly, following intervention, the rate of delayed colonoscopies due to inadequate preparations did not significantly change. We speculate that the availability of a novel mechanism to detect inadequate preparations prior to colonoscopy, the NBPAT, facilitated appropriate delay in colonoscopy when the preparation was inadequate; thus, while procedure delays did not decrease, overall procedure quality markedly increased.

This was a pragmatic process improvement study aimed to assess the effectiveness of an intervention in a real-world setting. Such studies are inherently limited in their study design. We implemented interventions simultaneously in order to minimize provider confusion and ease incorporation into the healthcare workflow, recognizing that the lack of a graded approach limits the ability to discern independent impacts.(25) Despite this limitation, we believe that the change from single-dose the day prior to split-dose bowel preparation with rescue preparation options standardized was the major driver of improved preparation quality while the automated and electronic orders facilitated communication and compliance. Recognizing that our interventions were higher quality than the current standard, our intention was to provide this best practice to all eligible patients. Thus, we compared our post-intervention cohort to a historical cohort rather than performing a randomized controlled study. The large sample size of each cohort and regression modeling attempt to minimize biases introduced through the historical cohort. There is the potential bias of Hawthorne effect amongst preparation raters. However, the sustained improvement in outcomes over a 12-month period despite changes in raters (trainees and faculty) between academic years and the objective reduction in repeat procedures due to inadequate preparation, which is unlikely to be influenced by the improvement initiative, suggests that rater bias may not substantially drive the improvement in outcomes. Additionally, the high intra- and inter-observer agreement amongst raters for the Aronchick and BBPS support the reliability of our primary outcome of bowel preparation adequacy. Finally, we were unable to fully compute cost savings due to unaccounted confounders which may influence hospital length of stay, management and costs; thus, our reported estimated cost savings is likely an underestimation as it does not account for costs of additional repeated procedures.

Our study suggests a marked improvement in inpatient bowel preparations through implementation of a structured interdisciplinary initiative. Following implementation, we observed a reduction in repeat procedures and hospitalization days following preparation. In the era of value-based healthcare, initiatives that trim costs while enhancing patient care are requisite; we have shown that such an initiative is feasible for inpatient colonoscopy. The success of this pragmatic study should serve as an impetus for other institutions to readdress their inpatient bowel preparation practices, and this model can serve as a framework to guide structural and procedural changes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the working group of gastroenterologists who helped to develop the inpatient bowel preparation algorithm: Dr. Greg Cohen, Dr. Ikuo Hirano, Dr. Colin Howden, Dr. Thomas Nealis, Dr. Kiran Nimmagadda, Dr. Christian Stevoff, and Dr. Arydas Vanagunas. Additionally, we would like to thank Dr. Audrey Calderwood and Dr. Tonya Kaltenbach for providing us with colonoscopy video clips.

Disclosures: RY: Supported by NIH T32DK101363

Abbreviations

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiology

- BBPS

Boston Bowel Preparation Score

- GI

Gastroenterology

- NBPAT

Nursing Bowel Preparation Assessment Tool

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

All authors approved the final version of the article.

Guarantor of article: Rena Yadlapati

Specific author contributions:

RY: Study oversight; study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; finalization of manuscript.

ERJ: Study concept and design; acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; finalization of manuscript.

AG: Study concept and design; acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; finalization of manuscript.

DLG: Analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; finalization of manuscript.

RC: Study concept and design; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; finalization of manuscript.

LW: Study concept and design; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; finalization of manuscript.

JDC: Analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; finalization of manuscript.

DPG: Acquisition of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; finalization of manuscript.

RNK: Study oversight; study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; finalization of manuscript.

Potential Conflict of Interest (Financial, Professional or Personal): None

References

- 1.Chorev N, Chadad B, Segal N, et al. Preparation for colonoscopy in hospitalized patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(3):835–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9591-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reilly T, Walker G. Reasons for poor colonic preparation with inpatients. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2004;27(3):115–7. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yadlapati R, Johnston ER, Gregory DL, et al. Predictors of Inadequate Inpatient Colonoscopy Preparation and Its Association with Hospital Length of Stay and Costs. Dig Dis Sci. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3761-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krygier D, Enns R. The inpatient colonoscopy: a worthwhile endeavour. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22(12):977–9. doi: 10.1155/2008/576987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebwohl B, Wang TC, Neugut AI. Socioeconomic and other predictors of colonoscopy preparation quality. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(7):2014–20. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller S, Francesconi CF, Maguilnik I, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing sodium picosulfate with mannitol on the preparation FOR colonoscopy in hospitalized patients. Arquivos de gastroenterologia. 2007;44(3):244–9. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032007000300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenfeld G, Krygier D, Enns RA, et al. The impact of patient education on the quality of inpatient bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24(9):543–6. doi: 10.1155/2010/718628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strate LL, Syngal S. Timing of colonoscopy: impact on length of hospital stay in patients with acute lower intestinal bleeding. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2003;98(2):317–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, et al. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(5):1179–87. e1–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen LB. Split dosing of bowel preparations for colonoscopy: an analysis of its efficacy, safety, and tolerability. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2010;72(2):406–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enestvedt BK, Tofani C, Laine LA, et al. 4-Liter split-dose polyethylene glycol is superior to other bowel preparations, based on systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2012;10(11):1225–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kilgore TW, Abdinoor AA, Szary NM, et al. Bowel preparation with split-dose polyethylene glycol before colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2011;73(6):1240–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marmo R, Rotondano G, Riccio G, et al. Effective bowel cleansing before colonoscopy: a randomized study of split-dosage versus non-split dosage regimens of high-volume versus low-volume polyethylene glycol solutions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(2):313–20. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee YJ, Kim ES, Park KS, et al. Education for Ward Nurses Influences the Quality of Inpatient’s Bowel Preparation for Colonoscopy. Medicine. 2015;94(34):e1423. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ettinger WH. Six Sigma: adapting GE’s lessons to health care. Trustee : the journal for hospital governing boards. 2001;54(8):10–5, 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milholland AV, Wheeler SG, Heieck JJ. Medical assessment by a Delphi group opinion technic. The New England journal of medicine. 1973;288(24):1272–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197306142882405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aronchick CA. Bowel preparation scale. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2004;60(6):1037–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02213-8. author reply 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calderwood AH, Jacobson BC. Comprehensive validation of the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2010;72(4):686–92. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helwick C. Optimizing Colonoscopy: Be (Adequately) Prepared. Endoscopy Suite. 2015;66(9) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, et al. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2009;69(3 Pt 2):620–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gluskin AKR, Johnston E, Gregory D, et al. The Nursing Bowel Preparation Assessment Tool is a Reliable and Accurate Inpatient Colonoscopy Clinical Decision Support Tool. Digestive Disease Week 2016. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen G, Howard J. Seaweed on the Beach: Reducing the Burden of Healthcare Waste. Explore. 2015;11(4):331–2. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Healthier Hospitals Initiative. 2012 [cited 2015 October 5]. Available from: http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=82.

- 24.Peery AF, Crockett SD, Barritt AS, et al. Burden of Gastrointestinal, Liver, and Pancreatic Diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berwick DM. The science of improvement. Jama. 2008;299(10):1182–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]