Abstract

Most countries have witnessed a dramatic increase of income inequality in the past three decades. This paper addresses the question of whether income inequality is associated with the population prevalence of depression and, if so, the potential mechanisms and pathways which may explain this association. Our systematic review included 26 studies, mostly from high‐income countries. Nearly two‐thirds of all studies and five out of six longitudinal studies reported a statistically significant positive relationship between income inequality and risk of depression; only one study reported a statistically significant negative relationship. Twelve studies were included in a meta‐analysis with dichotomized inequality groupings. The pooled risk ratio was 1.19 (95% CI: 1.07‐1.31), demonstrating greater risk of depression in populations with higher income inequality relative to populations with lower inequality. Multiple studies reported subgroup effects, including greater impacts of income inequality among women and low‐income populations. We propose an ecological framework, with mechanisms operating at the national level (the neo‐material hypothesis), neighbourhood level (the social capital and the social comparison hypotheses) and individual level (psychological stress and social defeat hypotheses) to explain this association. We conclude that policy makers should actively promote actions to reduce income inequality, such as progressive taxation policies and a basic universal income. Mental health professionals should champion such policies, as well as promote the delivery of interventions which target the pathways and proximal determinants, such as building life skills in adolescents and provision of psychological therapies and packages of care with demonstrated effectiveness for settings of poverty and high income inequality.

Keywords: Income inequality, depression, neo‐material hypothesis, social capital, social comparison, psychological stress, social defeat, low‐income populations

The unequal distribution of income and wealth has been growing steadily over the past three decades to astonishing levels, fuelled by the wide adoption of neo‐liberal economic policies and globalization. In 2016, while the bottom half of the global population collectively owned less than one percent of total wealth, the wealthiest top 10 percent owned 89 percent of all global assets1.

The growth of income and wealth inequality has been observed in countries at all levels of socio‐economic development. In the US, one of the richest countries in the world, the top 10 percent of the population now average nearly nine times as much income as the bottom 90 percent2. In India, an exemplar of a low‐ or middle‐income country (LMIC), the richest 1% owned nearly 60% of the total wealth of the country in 2016.

However, there is a three‐fold variation in the range of levels of inequality among countries, with the most equal countries mostly clustered in Western Europe and the most unequal countries comprising LMIC and the US. These variations at the country level, as well as at sub‐national levels (i.e., provinces or states) allow the exploration of the association between income inequality and a variety of social outcomes, notably health.

There is a robust body of evidence linking inequality and health outcomes, ranging from infant mortality and life expectancy to obesity. A compelling case for a causal relationship between inequality and a number of negative health outcomes has been recently presented3.

Not surprisingly, there is also evidence linking income inequality with mental health outcomes. A significant positive relationship has been reported between the incidence rate of schizophrenia and country‐level Gini coefficient, a widely used measure of the distribution of income or wealth in a population. A possible mechanism proposed for this association was that inequality impacts negatively on social cohesion and capital, and increases chronic stress, placing individuals at a heightened risk of schizophrenia4.

A review of studies on the association of income inequality and a range of mental health related outcomes reported heterogeneous findings, with about one third of studies observing a positive association between income inequality and the prevalence or incidence of mental health problems, one third observing mixed results for different subgroups, and one third observing no association5. Depression was one of the mental health outcomes considered in studies showing a positive association with income inequality.

Although potential mechanisms that underlie the observed association between income inequality and health have been proposed6, little is known about the mechanisms involved in the case of depression. Hence, there is a need for a systematic review focusing on this association which also sets out to identify potential mechanisms and develops a conceptual framework that can further our understanding and set an agenda for future research in the field.

The present study sought to advance the scientific inquiry of the association between income inequality and mental health in three specific ways. First, we systematically identified and descriptively synthesized the most updated literature on depression and income inequality, with a focus on study characteristics and potential differential impact by gender and level of poverty. Second, we quantitatively assessed the strength of the association of income inequality and depression prevalence through a meta‐analysis. Finally, we conducted a scoping review of the literature to explore the potential mechanisms, and developed a theoretical framework for this association.

By focusing on one mental health outcome (depression), we hoped to provide a more in‐depth analysis of potential mechanisms than has previously been possible. Our ultimate goal was to elaborate the implications of this body of evidence on policies which influence the distribution of income and wealth, and identify specific gaps in our knowledge which deserve further research investment.

METHODS

Systematic review and meta‐analysis

Search strategy

The search strategy was guided by our protocol (PROSPERO registration: CRD42017072721), which is available on request. In brief, we searched PubMed/Medline, EBSCO and PsycINFO databases. The search string used was “(depress* OR mental) AND (inequal* OR Gini)”. The electronic databases were searched for titles or abstracts containing these terms in all published articles between January 1, 1990 and July 31, 2017. The search was limited to studies published in English and involving human subjects. The reference lists of all included studies were hand‐searched for additional relevant reports or key terms. If new key terms were identified (new term included: “mood”), additional searches of the above databases were conducted and relevant papers were added until no further publications were found.

We included all studies providing primary quantitative data with a measure of depression or depressive symptoms as an outcome and any measure of income inequality at any geographical scale. Exclusion criteria were: unpublished data of any form including conference proceedings, case reports, dissertations; qualitative studies; and publications reporting duplicate data from the same population (in such cases, the report with the larger sample size was included).

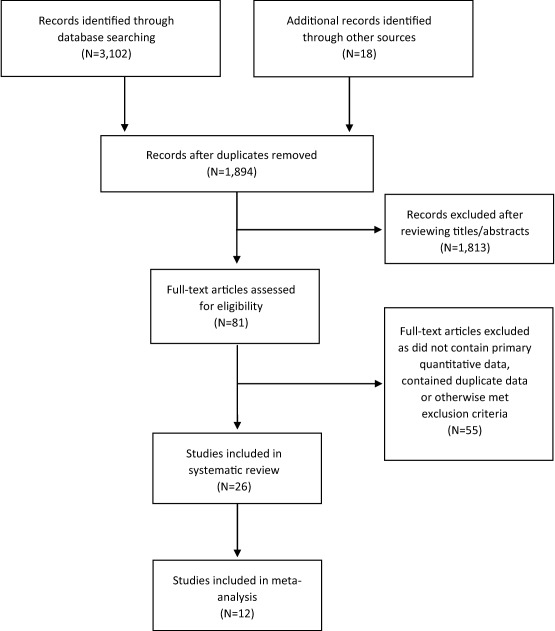

All titles and abstracts identified in the search were screened to exclude those that were obviously irrelevant based on the above exclusion criteria. Full‐text versions were obtained for all abstracts remaining after screening. Obtained full‐text articles were read and those not satisfying inclusion criteria were subsequently removed. The remaining articles were included in the systematic review (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Analyses

Study data were extracted onto a customized sheet. Quality assessments were independently performed by using the Systematic Appraisal of Quality in Observational Research (SAQOR) tool, that comprises six domains (each containing two to five questions): sample, control/comparison group, exposure/outcome measurements, follow‐up, confounders, and reporting of data7.

The SAQOR has been adapted for use in cross‐cultural psychiatric epidemiology studies8. In the current study, two domains were omitted (control/comparison group and follow‐up), as they were not applicable to any of the papers identified. A summary quality assessment was made by a single rater (JKB) for each of the four domains, and then an overall summary grade was determined based on adequacy in the four domains. The overall quality of each study was graded as high, moderate or low.

The meta‐analysis was conducted using Cochrane Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.39. Data were extracted from studies to calculate risk ratios for the association of income inequality and depression. Studies that included data on depression event rates stratified by income inequality were included in the meta‐analysis.

Compared to risk ratios, odds ratios exaggerate effect sizes, with the distortion most pronounced for outcomes with prevalence greater than 10%10, 11. Because depression prevalence may be greater than 10% in a population, risk is more accurately estimated with risk ratios. To calculate risk ratios, income inequality for each study was categorized as binary outcomes (higher vs. lower income inequality in a given population).

When income inequality was categorized into three or more groups, we re‐categorized the groups as follows: in studies with three groups, the lowest income inequality group was used as the reference and the medium and high inequality groups were collapsed; studies with four inequality groups were re‐categorized grouping the two lower and two higher inequality strata; for quintiles, the two low inequality quintiles were pooled as the reference group to compare with the three high inequality quintiles, which were collapsed into one stratum; finally, in studies with more than five inequality groups, these were re‐categorized into two strata of roughly equal sample size.

Unadjusted prevalence rates of depression were used whenever available, given the lack of consistency across studies in variables used for adjusting outcomes. When unadjusted prevalence rates were not available, demographics and other characteristics used for adjustment are reported. A random effects meta‐analysis was conducted because of the heterogeneity in design, populations and outcome measures.

We conducted sensitivity analyses using the leave‐one‐out approach to test the impact of excluding single studies contributing a disproportionately large effect. A forest plot of the risk ratios with summary statistics (pooled effect sizes) was completed using RevMan. Heterogeneity among trials was calculated using the I2 measure of inconsistency.

Scoping review of mechanisms

We searched the Introduction and Discussion sections of studies included in the systematic review, to identify authors’ hypothesized mechanisms of the relationship between inequality and depression. We subsequently considered hypothesized mechanisms in a recent review regarding the causal links between inequality and health3. We then compiled a list of hypothesized mechanisms based on their plausibility, specifically the extent to which the purported mechanisms were supported by the data reported in the included studies. We sought to improve the overall coherence by grouping different hypothesized mechanisms into conceptual categories.

Finally, we supplemented these findings with an analysis of the variability in findings from the studies included in our systematic review. This led to consideration of a number of other factors that might inform the hypothesized mechanisms, namely the geographical unit of analysis, level of national development of the study country, effects of income inequality on low‐ vs. high‐income groups, cultural variations across countries, broader political and historical context, life course or developmental stage factors, as well as gender and methodological considerations.

RESULTS

Systematic review and meta‐analysis

Searches of the listed databases using the search string as well as hand‐searching reference lists identified 1,894 potential articles. After screening titles or abstracts, 1,813 were removed as they were irrelevant or clearly did not contain primary data. Full‐text reports were retrieved for 81 articles, which were assessed for eligibility against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these, 55 were removed as they did not provide primary quantitative data on the relationship between income inequality and depression, contained duplicate data or otherwise met exclusion criteria. Thus, 26 studies were included in the systematic review (Table 1). The selection process for included studies is illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Papers included in the systematic review of the association between income inequality and depression

| Study | Sample | Study design | Country | Geographical unit of analysis | Inequality measure | Inequality range (Gini) | Depression measure | Absolute income effect | Gender effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive association (higher risk of depression in populations with higher income inequality) | ||||||||||

| Ahern & Galea12 | 1,355 adults aged 18 and over | Cross‐sectional | US | Local (neighbourhood) | Gini | 0.37‐0.51 | BSI‐D | Low income only | NA | |

| Burns et al4 | 25,936 adults aged 15 and over | Longitudinal panel | South Africa | District | P90/P10 ratio | 0.46‐0.68 | CES‐D | Low income only | No effect | |

| Chiavegatto Filho et al13 | 3,542 adults aged 18 and over | Cross‐sectional | Brazil | Municipality | Gini | 0.18‐0.34 (means for 1st and 3rd tertiles) | CIDI | NA | NA | |

| Cifuentes at al14 | 251,158 adults | Cross‐sectional | 65 countries | Country level | Gini | 0.25‐0.74 | DSM‐IV and DIPS | High HDI countries only | NA | |

| Fan et al15 | 293,405 adults aged 18 and over | Cross‐sectional | US | State | Gini | 0.40‐0.54 | PHQ | NA | NA | |

| Fiscella & Franks16 | 6,913 adults aged 25‐74 | Longitudinal | US | Local | Aggregate income earned by the poorer 50% of population divided by total aggregate income in the community | 0.18‐0.37 (ratio range) | GWB‐D | NA | NA | |

| Godoy et al17 | 655 adults aged 16 and over | Longitudinal panel | Bolivia | Local (village) | Gini | 0.71 ± 0.08 (mean±SD) | Feelings of “sadness” during past week | NA | NA | |

| Kahn et al18 | 8,060 women with children aged 26‐48 months | Cross‐sectional | US | State | Gini | 0.415‐0.430 (cut‐offs for 1st and 3rd tertiles) | CES‐D | Most pronounced in low‐income participants | Included only women | |

| Ladin et al19 | 22,777 adults aged 55 and over | Cross‐sectional | 10 European countries | Country level | Gini | 0.25‐0.36 | Euro‐D Scale | NA | NA | |

| Messias20 | 235,067 adults | Cross‐sectional | US | State | Gini | 0.410‐0.495 | PHQ | NA | NA | |

| Muntaner et al21 | 241 low‐income nursing assistants | Longitudinal | US | County | Gini | 0.31‐0.48 | RCES‐D | NA | NA | |

| Muramatsu22 | 6,640 adults aged 70 and over | Cross‐sectional | US | County | Gini | Not reported | CES‐D | No effect | NA | |

| Pabayo et al23 | 1,614 adolescents aged 14‐19 | Cross‐sectional | US | Local (census tract) | Gini | 0.33‐0.65 | MDS | NA | Effect only in girls | |

| Pabayo et al24 | 34,653 adults aged 18 and over | Longitudinal | US | State | Gini | 0.42‐0.45 (cut‐offs for 1st and 5th quintiles) | AUDADIS‐IV | No effect | Effect only in women | |

| Steptoe et al25 | 17,348 students aged 17‐30 | Cross‐sectional | 23 countries | Country level | Gini | 0.20‐0.59 | BDI | NA | NA | |

| Vihjalmsdottir et al26 | 5.958 adolescents aged 15‐16 | Cross‐sectional | Iceland | Local (neighbourhood) | 20%:20% ratio | 4.47‐39.90 (ratio range) | SCL‐90 (12 depression items) | NA | NA | |

| Equivocal association (positive in bivariate analysis but not in regression) | ||||||||||

| Choi et al27 | 34,994 adults aged 50 and over | Cross‐sectional | US | County | Gini | 0.33‐0.60 | CES‐D | NA | NA | |

| Goodman et al28 | 13,235 adolescents mean age 16 | Cross‐sectional | US | Local (school) | Proportion of total income held by the lower half of the population | 19.7‐40.5 (ratio range) | CES‐D | NA | NA | |

| Henderson et al29 | 42,862 adults aged 18 and over | Cross‐sectional | US | State | Gini | 0.38‐0.50 | AUDADIS‐IV | NA | Effect only in men in bivariate analysis | |

| No association | ||||||||||

| Fernández‐Niño et al30 | 8,874 adults aged 60 and over | Cross‐sectional | Mexico | State and municipal | Gini | Not reported | CES‐D | NA | NA | |

| Adjaye‐Gbewonyo et al31 | 9,664 adults | Longitudinal panel | South Africa | District | Gini | 0.46‐0.68 | CES‐D | NA | NA | |

| McLaughlin et al7 | 6,483 adolescents aged 13‐17 | Cross‐sectional | US | Local (census tract) | Gini | 0.59‐0.65 (cut‐offs for 1st and 4th quartiles) | CIDI (modified) | NA | NA | |

| Sturm & Gresenz32 | 9,585 adults | Cross‐sectional | US | Municipality | Gini | 0.38‐0.54 | CIDI | NA | NA | |

| Rai et al33 | 187,496 adults aged 18 and over | Cross‐sectional | 53 countries | Country level | Gini | 0.25‐0.74 | CIDI | No effect | NA | |

| Zimmerman et al34 | 4,817 adults aged 40‐45 | Cross‐sectional | US | County | County‐level percentage of households with income over $150,000 annually | Not reported | CES‐D | NA | NA | |

| Negative association (lower risk of depression in populations with higher income inequality) | ||||||||||

| Marshall et al35 | 10,644 adults aged 50 and over | Cross‐sectional | UK | Local (neighbourhood) | Gini | Not reported | CES‐D | Most salient in low‐income people | NA | |

BSI‐D – Brief Symptom Inventory Depression Scale, CES‐D – Center for Epidemiologic Studies ‐ Depression, CIDI – Composite International Diagnostic Interview, DIPS – Diagnosis Item Properties Study, HDI – human development index, PHQ – Patient Health Questionnaire, GWB‐D – General Well‐Being Schedule ‐ Depression subscale, RCES‐D – CES‐D Revised, AUDADIS‐IV – Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule ‐ IV, MDS – Modified Depression Scale, BDI – Beck Depression Inventory, SCL‐90 – Symptom Checklist ‐ 90, NA – not available

Study characteristics

The majority (N=18) of the 26 studies testing associations between income inequality and depression came from high‐income countries, with 15 studies reported from the US. In terms of geographical scale, four were conducted at the country level, 14 at regional level (state, county, district, municipality), and eight at local area or neighbourhood level.

A number of studies were conducted in specific populations: five in older persons only19, 22, 27, 30, 35; four in adolescents only7, 23, 26, 28; one in students aged 17–30 years25; and one in low‐income nursing assistants21.

The most common measure of depression, used in ten studies, was the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D), while four studies used the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), two the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ), and two the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule ‐ IV (AUDADIS‐IV). Each of the remaining eight studies utilized a different instrument. Godoy et al17 investigated 655 adults in villages within the Bolivian Amazon and found a positive relationship between village‐level Gini coefficient and experiences of “sadness” over the last seven days.

Income inequality was most commonly measured using the Gini coefficient (21 studies), with the remainder using a ratio measure (e.g., 20%:20% ratio; P90/P10 ratio). Notably, all country‐level studies utilized the Gini coefficient, while ratio measures were more commonly used in local area‐level studies (three out of eight) than in regional‐level studies (two out of 14).

Associations between income inequality and depression

Nearly two‐thirds (N=16, 61.5%) of studies found a significant positive relationship between income inequality and risk of depression, while another three (11.5%) reported a positive relationship that was significant in bivariate but not multivariate regression analysis. Six studies (23.1%) found no significant relationship, while only one (3.8%) reported a negative relationship between income inequality and risk of depression (Table 1).

Nineteen studies did not stratify their analysis by absolute income. Out of the seven studies that stratified analyses by absolute income, two showed a significant effect of income inequality on depression only in low‐income participants, and two demonstrated that the effect size was the strongest in low‐income individuals. Studies documenting greater effects in low‐income participants were conducted at either the regional (N=2) or the local level (N=2). The three studies reporting no absolute income effect were conducted at either the regional (N=2) or the country level (N=1).

Five studies stratified their analyses by gender. Of these, three found an association between income inequality and depression in females only18, 23, 24, one detected no gender effect4, and one found an association in men only in the bivariate analysis29.

Although none of the studies stratified the analyses by age group, several were conducted exclusively in adolescent or older adult populations, and some interesting observations can be made here. Of the four studies in adolescents only, three found a significant association between income inequality and depression (two in the regression23, 26 and one in bivariate analysis only28). Of the five studies in older adults only, three found an association between income inequality and depression (two in regression19, 22 and one in bivariate analysis only27), one found no association30, and one found a negative association35.

Participant ethnicity was reported in eight studies, with only three conducted in specific ethnic populations: in nearly 9,000 Hispanic adults aged 60 and older in Mexico30; in nearly 6,500 Black and Hispanic adolescents in the US7; and in Tsimane villagers in the Bolivian Amazon17. Notably, two of these latter studies did not find a relationship between income inequality and depression. Of the five studies that stratified their analysis by ethnicity, only one found an ethnicity effect, with the relationship between income inequality and depression most pronounced in middle‐class Blacks in a population representative panel in South Africa4.

Of the 26 studies, only six were longitudinal, allowing for temporal analyses. Of these, five reported a significant positive relationship between income inequality and depression4, 16, 17, 21, 24; and one reported no association31. All except two studies had large sample sizes of over 1,000 participants (ranging from 1,35512 to 293,40515).

Meta‐analysis

Twelve studies were included in the meta‐analysis, based on availability of event rates of depression to calculate risk ratios. Quality ratings of the included studies using SAQOR ranged from high to moderate (see Table 2). The pool of studies included six US studies, three multi‐country studies, one UK study, one Brazil study, and one South Africa study. Two of the US studies were limited to older adults. One study only included women18. One multi‐country study limited the sample to university students25.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of papers included in meta‐analysis (SAQOR tool)

| Paper | Sample | Exposure/outcome measures | Distorting influences | Reporting of data | Overall quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjaye‐Gbewonyo et al31/Burns et al4 | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | High |

| Ahern & Galea12 | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | High |

| Ladin et al19 | Adequate | Adequate | Unclear | Unclear | Moderate |

| Chiavegatto Filho et al13 | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | High |

| Kahn et al18 | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | Unclear | Moderate |

| Choi et al27 | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | High |

| Fan et al15 | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | High |

| Henderson et al29 | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | High |

| Cifuentes et al14 | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | Unclear | Moderate |

| Sturm & Gresenz32 | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | Inadequate | Moderate |

| Steptoe et al25 | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | Unclear | Moderate |

| Marshall et al35 | Unclear | Adequate | Adequate | Adequate | Moderate |

SAQOR – Systematic Appraisal of Quality in Observational Research

Four studies employed three strata of inequality13, 14, 18, 35; one study employed four strata12 and two studies employed quintiles15 . 29. All were re‐categorized as dichotomous as described earlier. Ladin et al19 divided the sample of ten European countries into five high inequality versus five low inequality countries. We followed a similar procedure for Steptoe et al's25 study of 23 countries, by creating a group of 11 low inequality countries and 12 high inequality countries.

For the South Africa data, we extracted information from the two studies that employed the South Africa National Income Dynamics Study4, 31. Data were available from Burns et al4 for the depression prevalence by municipality. Adjaye‐Gbewonyo et al31 calculated Gini coefficients for each municipality based on the 2011 census. We integrated depression prevalence data and Gini coefficient data by municipality and split the dataset into approximate halves around a Gini coefficient of 0.75.

Unadjusted data were used for all studies when available. Unadjusted data were not presented in the study by Cifuentes et al14, and rates were adjusted for age, gender and marital status. Fan et al15 only presented adjusted prevalence figures: rates were adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, household income, and chronic medical conditions.

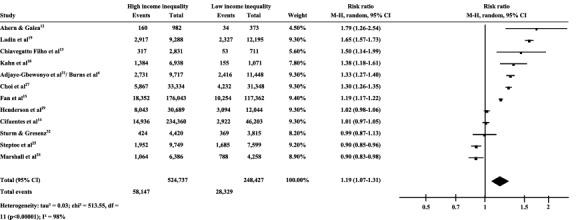

Based on the 12 studies with dichotomized inequality groupings, the pooled risk ratio was 1.19 (95% CI: 1.07‐1.31), demonstrating greater risk of depression in populations with higher income inequality relative to those with lower income inequality (see Figure 2). The heterogeneity was very high, I2=98%, which is likely due in part to the diversity of sample designs, populations, measures used, and adjustments and weighting in analyses. In all sensitivity analyses, the pooled risk ratio was significant for higher income inequality associated with increased risk of depression (p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the association between income inequality and depression. M‐H – Mantel‐Haenszel estimate, total – pooled risk ratio

Multiple studies conducted moderator analyses by stratifying the samples by gender, absolute income, country economic status, and ethnicity/race. Because of the limited number of studies with outcomes that could be dichotomized by depression and income inequality, we did not create subpools of studies or employ meta‐regression to assess these potential moderators.

Scoping review of mechanisms

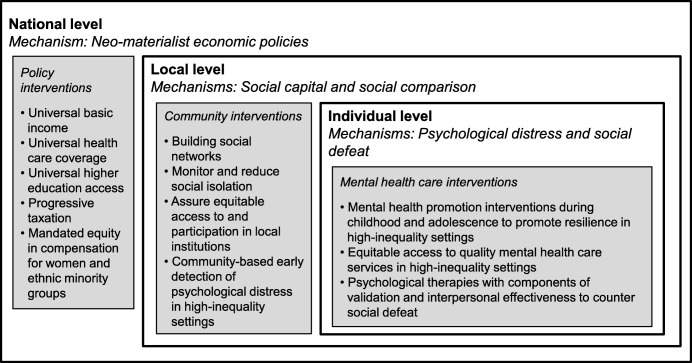

Based on the results of the systematic review, a number of potential mechanisms of the inequality‐depression relationship may be hypothesized, operating at different ecological levels, from the individual to the neighbourhood to the regional or national levels.

At the individual level, the effects of income inequality on general health are likely to be primarily mediated through psychological stress3. This may be regarded as the final mechanism mediating the effects of income inequality on depression in a range of pathways.

At the neighbourhood levels, two mechanisms are hypothesized. The first is the social comparison or status anxiety hypotheses36, which argue that comparing oneself to those who are better off in a highly unequal context creates feelings of social defeat or status anxiety4, 37. In a similar vein, Walker et al38 hypothesized feelings of withdrawal and shame experienced by those in lower social positions. The second neighbourhood mechanism is the social capital hypothesis, which argues that income inequality erodes social capital, including two key components: cognitive social capital (especially social trust)26 and structural social capital (the organizational and structural arrangements which facilitate social interactions and build social trust and cooperation, for example through group membership)39.

Social capital is critical, because it facilitates social integration (a dynamic process by which members of a social group participate in dialogue or collaborate to achieve a shared social goal). Income inequality therefore undermines social capital and social integration, promoting social isolation, alienation and loneliness. It also undermines perceptions of fairness (a component of trust)37. Ichida et al40 confirmed the social capital hypothesis in Japan, showing that social capital (measured as social trust) mediated the effect of inequality on self‐rated health. This is supported by Durkheim's theory of social integration and social regulation41, the failure of which he linked to suicide.

Perceptions of fairness and trust are also consistent with Merton's anomie disjunction between society's goals and normative structures governing the means to attain that goal42. This is more exaggerated in societies with higher levels of inequality, where the means of attaining upward social mobility are severely constrained, and therefore there is a disjunction between society's goals or aspirations (for example of acquiring wealth) and the means to attain that goal, which are not accessible to those who are lower on the socio‐economic hierarchy.

Both the above neighbourhood mechanisms may be more pronounced at certain developmental stages, in particular in adolescence, when social trust and group membership are being established, and when most mental health problems emerge. For example, social status was associated with depression among adolescents whose parents had lowest levels of education7. In addition, social comparison may be amplified by other group identities, for example ethnicity or gender.

At the national or regional levels, the neo‐material hypothesis proposes that greater income inequality coexists with a wide range of material deprivations which are relevant to health43. These include lack of investment in housing, education and public transport as well as pollution control, healthy food availability and accessibility of health care. Thus, greater inequality leads to worse physical health (for example due to less public spending on health care in more unequal societies), leading in turn to an increased rate of depression.

This hypothesis was supported by Muramatsu22, who found that the association between inequality and depression was stronger among those with more illnesses. However, it is worth noting Zimmerman et al's opposite finding that more unequal states did not in fact spend less on health care34. Also, Fone et al36 argue that it is unlikely that the neo‐material hypothesis would apply at small area level (such as neighbourhoods), as resource allocation decisions for major services are not typically made within these areas.

For all of these potential mechanisms, it is important to consider a range of other factors that may moderate the relationship between income inequality and depression, reflected in the available studies. The first is the geographical unit of analysis. Of the six studies that found no association, five conducted analysis at the district level, and national level effects appeared to be more marked in the studies included in this review. According to Ahern and Galea12, this is likely to be at least partially influenced by the nature of the area demarcation. For example, if a neighbourhood includes strong contrasts of high‐ versus low‐income groups, the effect of income inequality is likely to be more pronounced at that neighbourhood level. But frequently neighbourhoods involve homogeneous demarcations, and the effect may then be less pronounced.

In a similar vein, Fone et al36 found that in Wales income deprivation was more important than income inequality for common mental disorders at the local neighbourhood level, but that the effect of income inequality became more evident at larger regional levels. Furthermore, Chen and Crawford44 reported that, when comparing US counties and states, the income inequality/health relationship was more evident at the state than the county level, (although this was true for health insurance as an outcome but not for self‐reported health). Thus, it may be possible to argue that different mechanisms operate at different geographical levels or units of analysis.

A second important consideration is the level of national development, for example as measured using the human development index (HDI). One study showed a possible interaction with country HDI level, namely that the inequality/depression association was more evident in higher HDI countries14. Income inequality may matter in high‐income countries with low levels of poverty, but not in low‐ or middle‐income countries with high levels of poverty, where the effects of material poverty and absolute income may be more significant.

A third consideration is the effect of income inequality on low‐ vs. high‐income groups. Within countries, the effect of inequality on depression appears to be more pronounced among low‐income groups12. This is consistent with the hypothesized role of upward social mobility, the constraints of which are more likely to be experienced by low‐income groups. The hypothesis that inequality is deleterious for high‐income groups too is proposed by other authors3. Kawachi et al45 argue that the wealthy in highly unequal societies cannot escape the “pathologies of poverty”, including crime, violence and exposure to some infectious diseases.

A fourth consideration is cultural variation across countries. Although this may be difficult to test empirically, Steptoe et al25 considered the results in a multi‐country study with respect to cultural variation along the axis of individualism and collectivism. The likelihood of high levels of depressive symptoms was lower in more individualistic cultures, with 26% reduction in the odds of elevated symptoms with every unit change in individualism‐collectivism score.

A fifth consideration is the broader political and historical context within which depression and inequality are measured. For example, in post‐apartheid South Africa, there have been expectations of rapid social improvements, and there is clear evidence of improvements for some people, but for those who remain in poverty there is a sense of frustration, alienation, disappointment and anger, manifest in frequent service delivery protests4. This may well exaggerate the effects of income inequality on depression.

A sixth consideration is life course or developmental stage. According to one study, childhood social class is more predictive of self‐rated health than adult social class16. Prevalence of depression varies substantially across the life course46, and early exposure to inequality may well affect later mental health. Most of the studies included in this review lack a life course or developmental framework, even when the effect of inequality on specific age groups was examined, for example in the case of adolescent depression.

A seventh consideration is gender. In at least one study23, the effect of inequality on depression was found for adolescent girls but not for boys. This was confirmed by Hiilamo47 in a study in Finland, which explored changes in municipality‐level relative poverty and antidepressant prescriptions from 1995 to 2010, and found a positive association for young adult females.

A final consideration is the methods employed by the studies themselves. For example, contrary to the finding that the association between inequality and depression was less evident in more local, homogeneous populations, Fiscella and Franks16 did find a positive association at local level. This finding may be attributable to the study design, which employed longitudinal, multi‐level methods and collected baseline data on county income inequality, individual income, age, gender, self‐rated health, level of depressive symptoms, and severity of biomedical morbidity.

DISCUSSION

In this paper we present, to our knowledge, the most comprehensive review of the evidence on the relationship between income inequality and depression. Despite the relatively small evidence base (especially from LMIC) and methodological limitations of the available studies, we report a compelling quantitative association between income inequality and depression. Even though the absolute effect size was relatively small (risk ratio of 1.19), the translation of this risk to population mental health is likely to be very large.

Further, we note that the primary outcome of the studies we included was a categorical outcome of “case‐level” depression. This is a crude indicator of population mental health, and the associations between income inequality and mood are likely to be greater when the latter is treated as a continuous dimension, which could capture dose‐effects of the degree of inequality on the distribution of affective symptoms.

If our findings are indicative of a causal relationship, then we should expect worse mental health globally in the years ahead, as income inequality is continuing to increase in most countries, making the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goal targets for mental health48 even harder to achieve. This is especially likely to be the case for disadvantaged or vulnerable groups in the population that already bear a disproportionate burden of mental health problems, such as women, adolescents, older adults and low‐income groups.

The heterogeneity of the findings of studies across populations and over time is not surprising, given the complexity of likely mechanisms and pathways, and their moderation by a range of contextual factors which we have attempted to delineate. These mechanisms operate at different ecological levels, but the final pathways are, as with any mental health problem, uniquely individual, moderated by a range of distal and proximal determinants.

Although we do strongly endorse the need to “unpack” these mechanisms through carefully designed studies, such research is likely to be complex, time‐consuming and costly. Thus, we propose that the evidence which already exists is sufficient to take pre‐emptive action to halt the potentially damaging effects of income inequality on the mental health of populations.

Implications for reducing the global burden of depression

Our ecological framework offers indications for the kinds of interventions which hold promise (see Figure 3). Obviously, at the national or regional level, economic policies which promote the fair distribution of income, for example through a universal basic income and progressive taxation, are potentially the most tractable49. Additionally, promoting social policies that reduce gender inequities which systematically disadvantage women, and income inequities, such as universal health coverage and expanding opportunities for educational attainment, can reduce the impact of the neo‐material effect on low‐income populations.

Figure 3.

Mechanisms of income inequality on depression by ecological levels and recommendations for interventions

In addition to structural interventions, the mechanisms we propose suggest attractive opportunities for proximal interventions to mitigate the adverse personal consequences of living in unequal societies. The Disease Control Priorities project50 has recommended a series of interventions for the prevention, treatment and care of mental health problems, most of which can be delivered through community and routine health care platforms, using task‐sharing by non‐specialist providers. Particularly relevant examples would include interventions in early life through adolescence to build resilience (for example, parenting interventions and life skills interventions), as well as promoting early detection and self‐help for mood and anxiety disorders (for example, through improving access to empirically supported digital apps, especially with guidance)51.

A recent systematic review has demonstrated the effectiveness of psychological therapies delivered by non‐specialists in low‐resource settings52. Such therapies may be modified when delivered in the context of high inequality through a focus on mechanisms related to cognitive comparisons leading to social defeat and worthlessness. For example, interventions that focus on demoralization53, 54 may be especially important in highly inequitable societies and communities. Third‐wave psychological therapies that include components of self‐validation may also counter social defeat and worthlessness associated with depression and suicidality55. These therapies are currently being adapted for delivery in settings of extreme poverty56.

Interventions that harness the power of social networking sites to build social capital also show promise at mobilizing specific subgroups and reducing the risk of social isolation. Pilot programs in Mexico and South Africa have shown encouraging results at reducing levels of anxiety, depression and feelings of social isolation in adolescents and pregnant women with HIV/AIDS57, 58, 59, 60. Marshall et al35 report that social interactions and networks among subgroups in mixed‐income neighbourhoods cushion the impact of income inequality on depression.

Other research points to the role of social interactions, cultural biases and belief systems in maintaining and perpetuating conditions for income inequality61, 62. Thus, it is important that we develop interventions that target social and cultural aspects of inequalities (for example, designing institutional platforms such as schools and health institutions) to enhance social capital, and all interventions must be guided by a strong emphasis on equitable coverage. This is consistent with a shift from cultural competency to “structural competency”, which emphasizes the need for mental health providers to be knowledgeable of context and resources of their patients and actively draw upon resources to mitigate social and structural determinants of mental illness63.

Limitations of the study

There are limitations to our study which should be noted. First, publication bias, namely a propensity for journals to publish positive findings, may overestimate the strength or consistency of the association between inequality and depression. Second, there was a heterogeneity of outcome measures for depression, with some studies not utilizing validated assessment instruments, and a diversity in sample size and sampling strategies, all of which impact depression prevalence estimates64. Third, the majority of studies failed to stratify their samples by important socio‐demographic factors such as gender, age and absolute income, limiting our ability to explore in greater depth the controversial question of whether the negative effects of income inequality are evenly distributed across the population or if certain vulnerable groups are particularly affected65.

Regarding the meta‐analysis, we were unable to use unadjusted data across all studies, and it is likely that the studies that adjusted inequality by outcomes reflect aspects of the association differently than unadjusted studies. In addition, the inequality cut‐off for each study was different, based on the relative levels of inequality within the sample. For example, inequality levels within the South Africa dataset were high on average compared to European nations. Therefore, our findings are reflective of regional and national relative income inequality rather than the effect of absolute inequality (e.g., dividing all samples at one specific Gini coefficient cut‐off, which would have been arbitrary, given that inequality is, by definition, a relative measure).

The meta‐analysis also demonstrated high heterogeneity. As the pool of studies examining income inequality and mental health grows, it will be possible to perform more subgroup analyses with studies that employ comparable designs and samples in order to reduce heterogeneity.

Implications for research

Future research should aim to unpack the mechanisms underlying the association between inequality and depression, in particular to explain the heterogeneity of findings across contexts. This research should involve prospective studies in diverse countries, in particular in a range of LMIC which are witnessing rapid socio‐economic changes, such as the BRICS nations. Notably, Brazil and South Africa, which both have high levels of inequality, showed comparable high effects of income inequality on depression in our meta‐analysis (risk ratios were 1.38 and 1.33 respectively).

Future studies should include the effects of changes in income inequality (at different geographical levels and population subgroups of analysis) over time, with embedded assessments of hypothesized individual and area‐level mechanisms; and evaluation of the effects of interventions addressing the proposed pathways. Additionally, further exploration of the studies with equivocal findings, such as countries with high levels of income inequality which did not show an increased prevalence of depression, should also be conducted, to understand possible structural differences, policies or socio‐cultural factors that mitigate this effect.

It is important to methodologically take note of the historical, political and cultural forces that may shape the association between income inequality and depression in developing countries. Modelling contextually grounded forces can shed greater light on the precise mechanisms that may be operating in these contexts.

CONCLUSIONS

Mental health professionals, regardless of their political persuasion, should carefully assess the evidence presented in this review to shape their position with respect to the ideologically contentious issue of income inequality.

They should ally with other stakeholders in government and civil society who are arguing for a fairer, more equitable distribution of income, as this is a major social determinant of poor mental health, while also drawing attention to the need for greater investments in proven individual interventions for the prevention and treatment of depression.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

V. Patel is supported by a Wellcome Trust Principal Research Fellowship and by the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (U19MH113211). B.A. Kohrt is supported by the US NIMH (grants K01MH104310 and R21MH111280). V. Patel and C. Lund are supported by UK Aid, as part of the PRogramme for Improving Mental health carE (PRIME). The views expressed in this paper are not necessarily those of the funders.

REFERENCES

- 1. Davies J, Lluberas R, Shorrocks A. Credit Suisse Global Wealth Databook 2016. Zurich: Credit Suisse Research Institute, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inequality.org. Income inequality in the United States. https://inequality.org/facts/income-inequality/.

- 3. Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. Income inequality and health: a causal review. Soc Sci Med 2015;128:316‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burns JK, Tomita A, Lund C. Income inequality widens the existing income‐related disparity in depression risk in post‐apartheid South Africa: evidence from a nationally representative panel study. Health Place 2017;45:10‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ribeiro WS, Bauer A, Andrade MC et al. Income inequality and mental illness‐related morbidity and resilience: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4:554‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wilkinson R, Pickett K. Inequality and mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4:512‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McLaughlin KA, Costello EJ, Leblanc W et al. Socioeconomic status and adolescent mental disorders. Am J Publ Health 2012;102:1742‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kohrt BA, Rasmussen A, Kaiser BN et al. Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 2013;43:365‐406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cochrane Community . Review Manager (RevMan). https://gradepro.org/.

- 10. Egger M, Smith GD, Phillips AN. Meta‐analysis: principles and procedures. BMJ 1997;315:1533‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Viera AJ. Odds ratios and risk ratios: what's the difference and why does it matter? South Med J 2008;101:730‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ahern J, Galea S. Social context and depression after a disaster: the role of income inequality. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:766‐70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chiavegatto Filho AD, Kawachi I, Wang YP et al. Does income inequality get under the skin? A multilevel analysis of depression, anxiety and mental disorders in Sao Paulo, Brazil. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:966‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cifuentes M, Sembajwe G, Tak S et al. The association of major depressive episodes with income inequality and the human development index. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:529‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fan AZ, Strasser S, Zhang XY et al. State‐level socioeconomic factors are associated with current depression among US adults in 2006 and 2008. J Publ Health Epidemiol 2011;3:462‐70. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fiscella K, Franks P. Individual income, income inequality, health, and mortality: what are the relationships? Health Serv Res 2000;35:307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Godoy RA, Reyes‐García V, McDade T et al. Does village inequality in modern income harm the psyche? Anger, fear, sadness, and alcohol consumption in a pre‐industrial society. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:359‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kahn RS, Wise PH, Kennedy BP et al. State income inequality, household income, and maternal mental and physical health: cross sectional national survey. BMJ 2000;321:1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ladin K, Daniels N, Kawachi I. Exploring the relationship between absolute and relative position and late‐life depression: evidence from 10 European countries. Gerontologist 2010;50:48‐59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Messias E. Income inequality, illiteracy rate, and life expectancy in Brazil. Am J Publ Health 2003;93:1294‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Muntaner C, Li Y, Xue X et al. County level socioeconomic position, work organization and depression disorder: a repeated measures cross‐classified multilevel analysis of low‐income nursing home workers. Health Place 2006;12:688‐700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Muramatsu N. County‐level income inequality and depression among older Americans. Health Serv Res 2003;38:1863‐84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pabayo R, Dunn EC, Gilman SE et al. Income inequality within urban settings and depressive symptoms among adolescents. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016;70:997‐1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pabayo R, Kawachi I, Gilman SE. Income inequality among American states and the incidence of major depression. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:110‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steptoe A, Tsuda A, Tanaka Y. Depressive symptoms, socio‐economic background, sense of control, and cultural factors in university students from 23 countries. Int J Behav Med 2007;14:97‐107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vilhjalmsdottir A, Gardarsdottir RB, Bernburg JG et al. Neighborhood income inequality, social capital and emotional distress among adolescents: a population‐based study. J Adolesc 2016;51:92‐102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Choi H, Burgard S, Elo IT et al. Are older adults living in more equal counties healthier than older adults living in more unequal counties? A propensity score matching approach. Soc Sci Med 2015;141:82‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goodman E, Huang B, Wade TJ et al. A multilevel analysis of the relation of socioeconomic status to adolescent depressive symptoms: does school context matter? J Pediatr 2003;143:451‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Henderson C, Liu X, Roux AV et al. The effects of US state income inequality and alcohol policies on symptoms of depression and alcohol dependence. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:565‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fernández‐Niño JA, Manrique‐Espinoza BS, Bojorquez‐Chapela I et al. Income inequality, socioeconomic deprivation and depressive symptoms among older adults in Mexico. PLoS One 2014;9:e108127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Adjaye‐Gbewonyo K, Avendano M, Subramanian SV et al. Income inequality and depressive symptoms in South Africa: a longitudinal analysis of the National Income Dynamics Study. Health Place 2016;42:37‐46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sturm R, Gresenz CR. Relations of income inequality and family income to chronic medical conditions and mental health disorders: national survey. BMJ 2002;324:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rai D, Zitko P, Jones K et al. Country‐ and individual‐level socioeconomic determinants of depression: multilevel cross‐national comparison. Br J Psychiatry 2013;202:195‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zimmerman FJ, Bell JF. Income inequality and physical and mental health: testing associations consistent with proposed causal pathways. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:513‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marshall A, Jivraj S, Nazroo J et al. Does the level of wealth inequality within an area influence the prevalence of depression amongst older people? Health Place 2014;27:194‐204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fone D, Greene G, Farewell D et al. Common mental disorders, neighbourhood income inequality and income deprivation: small‐area multilevel analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2013;202:286‐93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Buttrick NR, Oishi S. The psychological consequences of income inequality. Soc Pers Psychol Compass 2017;11:e12304. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walker R, Kyomuhendo GB, Chase E et al. Poverty in global perspective: is shame a common denominator? J Soc Policy 2013;42:215‐33. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Glass R. Social capital and self‐rated health: a contextual analysis. Am J Publ Health 1999;89:1187‐93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ichida Y, Kondo K, Hirai H et al. Social capital, income inequality and self‐rated health in Chita peninsula, Japan: a multilevel analysis of older people in 25 communities. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:489‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Durkheim É. Suicide: a study in sociology. New York: Free Press, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Merton RK. Social theory and social structure. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lynch JW, Smith GD, Kaplan GA et al. Income inequality and mortality: importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment, or material conditions. BMJ 2000;320:1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen Z, Crawford CA. The role of geographic scale in testing the income inequality hypothesis as an explanation of health disparities. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:1022‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kawachi I, Berkman L. Social cohesion, social capital, and health In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I. (eds). Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000:174‐90. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;382:1575‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hiilamo H. Is income inequality ‘toxic for mental health’? An ecological study on municipal level risk factors for depression. PLoS One 2014;9:e92775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. United Nations . Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Piketty T. Capital in the twenty‐first century. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Patel V, Chisholm D, Dua T. et al (eds). Mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: disease control priorities, 3rd ed Washington: World Bank Publications, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Araya R et al. Digital technology for treating and preventing mental disorders in low‐income and middle‐income countries: a narrative review of the literature. Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4:486‐500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Singla DR, Kohrt BA, Murray LK et al. Psychological treatments for the world: lessons from low‐and middle‐income countries. Ann Rev Clin Psychol 2017;13:149‐81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Noordhof A, Kamphuis JH, Sellbom M et al. Change in self‐reported personality during major depressive disorder treatment: a reanalysis of treatment studies from a demoralization perspective. Personal Disord (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Griffith JL. Hope modules: brief psychotherapeutic interventions to counter demoralization from daily stressors of chronic illness. Acad Psychiatry (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hayes SC. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behav Ther 2004;35:639‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ramaiya MK, Fiorillo D, Regmi U et al. A cultural adaptation of dialectical behavior therapy in Nepal. Cogn Behav Pract 2017;24:428‐44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. McClure CM, McFarland M, Legins KE. Commentary: innovations in programming for HIV among adolescents: towards an AIDS‐free generation. JAIDS 2014;66:S224‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.The SHM Foundation. Zumbido health. http://shmfoundation.org/.

- 59.The SHM Foundation. Project Kopano. https://shmfoundation.org/.

- 60.The SHM Foundation. Project Khulama. https://shmfoundation.org/.

- 61. Bowles S, Durlauf SN, Hoff K. (eds). Poverty traps. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hoff KR, Pandey P. Belief systems and durable inequalities: an experimental investigation of Indian caste. Washington: World Bank Publications, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Metzl JM, Hansen H. Structural competency: theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med 2014;103:126‐33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta‐analysis 1980–2013. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:476‐93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Almeida‐Filho N. A glossary for health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002;56:647‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]