Abstract

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is the causative agent of a fatal malignancy known as adult T-cell leukemia (ATL). One way to address the pathology of the disease lies on conducting research with a molecular approach. In addition to the analysis of ATL-relevant signaling pathways, understanding the regulation of important and relevant transcription factors allows researchers to reach this fundamental objective. HTLV-1 encodes for two oncoproteins, Tax and HTLV-1 basic leucine-zipper factor, which play significant roles in the cellular transformation and the activation of the host’s immune responses. Activating protein-1 (AP-1) transcription factor has been linked to cancer and neoplastic transformation ever since the first representative members of the Jun and Fos gene family were cloned and shown to be cellular homologs of viral oncogenes. AP-1 is a dimeric transcription factor composed of proteins belonging to the Jun (c-Jun, JunB, and JunD), Fos (c-Fos, FosB, Fra1, and Fra2), and activating transcription factor protein families. Activation of AP-1 transcription factor family by different stimuli, such as inflammatory cytokines, stress inducers, or pathogens, results in innate and adaptive immunity. AP-1 is also involved in various cellular events including differentiation, proliferation, survival, and apoptosis. Deregulated expression of AP-1 transcription factors is implicated in various lymphomas such as classical Hodgkin lymphomas, anaplastic large cell lymphomas, diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, and adult T-cell leukemia. Here, we review the current thinking behind deregulation of the AP-1 pathway and its contribution to HTLV-induced cellular transformation.

Keywords: AP-1, HTLV-1, antisense transcription, leukemia, HBZ, JunD

Introduction

The human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) was the first pathogenic retrovirus identified in human (Matsuoka and Jeang, 2010). It is estimated that 10–15 million individuals are infected with HTLV-1 around the world, with endemic areas in the Caribbean, southern Japan, Central and South America, Iran, Melanesia, and sub-Saharan Africa (Sonoda et al., 2011; Gessain and Cassar, 2012). While the vast majority of HTLV-1-infected individuals remain clinically asymptomatic, around 5% of them will develop a highly aggressive T-cell malignancy, termed adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) (Matsuoka and Jeang, 2007; Kogure and Kataoka, 2017). ATL presents four distinct clinical stages ranging from smoldering to acute leukemia. It generally occurs in individuals infected around the time of birth eventually and it develops only after prolonged incubation periods ranging from 20 to 60 years (Matsuoka et al., 1997). Although several studies have reported that the proviral DNA load is a critical factor for promoting disease progression in infected individuals (Olindo et al., 2005; Iwanaga et al., 2010; Yoshida, 2010), 30 years after its characterization in T-lymphocytes from leukemic patients, it is still not fully understood how HTLV-1 transforms human CD4+ T cells in a stepwise fashion. The current view is that pleiotropic functions of the HTLV-1 viral transcriptional transactivator Tax (Peloponese et al., 2007; Journo et al., 2009), such as deregulation of the signaling pathways AP-1 pathway (Fujii et al., 2000) and NF-kB (Rosin et al., 1998; Peloponese et al., 2006; Chan and Greene, 2012), and inactivation of tumor suppressors (Tabakin-Fix et al., 2006) are promitotic events, which drive CD4+ T-cell proliferation during the preleukemic stage (Matsuoka and Jeang, 2007). Paradoxically, fresh ATL cells lack Tax expression, due to genetic and epigenetic modifications in the HTLV-1 provirus (Tamiya et al., 1996; Kataoka et al., 2015). In contrast, HTLV-1 basic leucine-zipper factor (HBZ) mRNA which is encoded by the complementary strand of the HTLV-1 genome is expressed in all ATL cells (Mesnard et al., 2006; Matsuoka and Green, 2009). Recent studies have provided striking evidence for the important role played by of HBZ and the AP-1 pathway in HTLV-1 pathogenesis. In this review, we will limit our focus to the role of AP-1 activation by Tax and HBZ and discuss, in a non-exhaustive manner, how this activation relates to oncogenesis and inflammation.

The AP-1 Pathway, A Key Regulator of Cellular Transformation

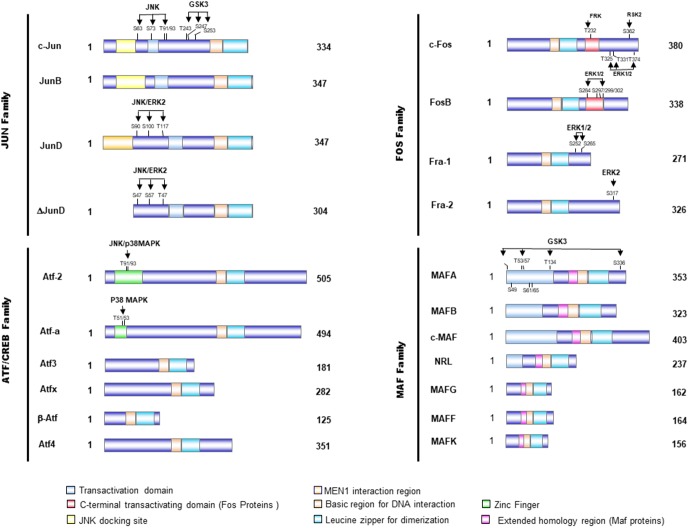

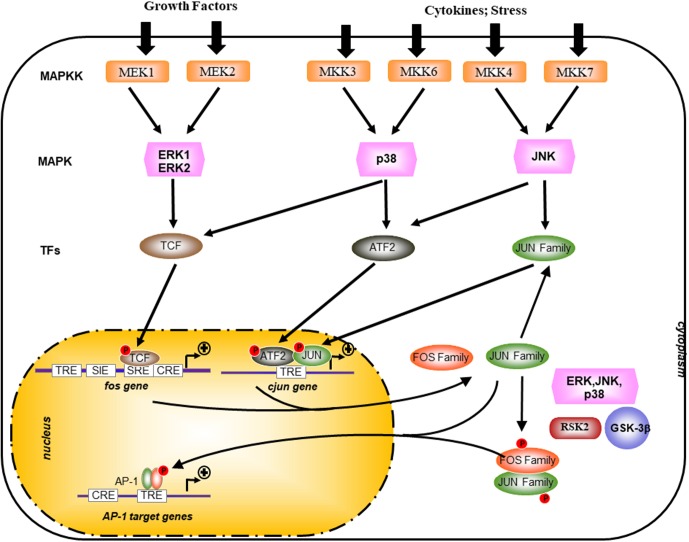

Activating protein-1 (AP-1) transcription factor has been linked to cancer and neoplastic transformation since the first cloning of jun and fos proto-oncogenes were cloned following their identification as cellular homologs of avian sarcoma virus 17 (ASV 17)-encoded oncogenes vjun and vfos 30 years ago (Curran and Franza, 1988). AP-1 is composed of 18 dimeric complexes which included members of four families of DNA-binding proteins: Jun family (c-Jun, JunB, v-Jun, JunD), Fos family (c-Fos, FosB, Fra-1, and Fra-2,) ATF/cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding (CREB) (activating transcription factor: ATF1–4, ATF-6, b-ATF, ATFx), and Maf family (musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma c-Maf, MafA, MafB, MafG/F/K, and Nrl) (Eferl and Wagner, 2003; Milde-Langosch, 2005; Hernandez et al., 2008; Figure 1). Transcriptional activity of AP-1 is regulated by a wide array of cellular stimuli including growth factors, bacterial and viral infection, cytokines, UV radiation, and cellular stress (Eferl and Wagner, 2003; Milde-Langosch, 2005; Hernandez et al., 2008; Figure 1). These transcription factors have critical functions in wide variety of cellular processes, including inflammation, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (Eferl and Wagner, 2003; Milde-Langosch, 2005; Hernandez et al., 2008). The activity of the different AP-1 dimer also depends on the cell type and its differentiation state. In response to external stimuli, MAPK activity increases and regulates both the abundance and transactivating capacities of Jun, Fos, and ATF (Figure 2). MAPKs are a serine/threonine kinase superfamily that comprises extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK), c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases (JNK), p38, and c-Fos-regulating kinases (FRK) (Cavigelli et al., 1995; Karin, 1995; Srivastava et al., 1999). The regulation of AP-1 is complex and occurs at multiple levels, ranging from dimer composition, to transcriptional and post-translational events, and to specific interactions between AP-1 proteins and other transcription cofactors (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Schematical presentation of the structure of AP-1 proteins. Activator protein 1 (AP-1) proteins include the JUN, FOS, activating transcription factor (ATF), and musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (MAF) protein families, which can form homodimers and heterodimers through their leucine-zipper domains. The AP-1 proteins exhibit several domains, including the bZIP domain (leucine zipper plus basic domain), transactivation domains, and docking sites for several kinases, such as JNK or ERK. These kinases modulate the activity of those transcription factors by phosphorylation of serine and threonine residues.

FIGURE 2.

Transcriptional and post-translational activation of AP-1. AP-1 activity is stimulated by external stimuli like growth factors or inflammatory cytokines and a complex network of kinase such as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) of the extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK), p38, and JUN amino-terminal kinase (JNK) families. Posttranslational phosphorylation by various kinases regulates AP-1 activity, which includes its transactivating potential, DNA-binding capacity, and the stability of AP-1 components. GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3β; MAPKK, MAPK kinase; RSK2, ribosomal S6 kinase 2; TCF, ternary complex factor; SRE, serum-response element; TRE, TPA-responsive element; CRE, cAMP-response element; SIE, Sis-inducible element.

AP-1 Transcriptional Regulation

Activating protein-1 activity is modulated through its dimer composition which is determined by the differential expression of Jun, Fos, ATF, and Maf families (Figure 1) and through the sequence of the AP-1 DNA-binding sites (Table 1). The abundance of the subunits can be controlled either via the regulation of the synthesis and stability of respective mRNAs or via the regulation of protein stability (for example, stimulus-dependent degradation via the ubiquitin pathway) (Musti et al., 1996). Most of the genes that encode AP-1 subunits behave as “immediate-early” genes. Indeed, they are rapidly but transiently transcribed in response to extracellular stimuli, such as growth factor (Ryder and Nathans, 1988; Karin et al., 1997) and cellular stress (Angel and Karin, 1991; Zhou et al., 2007; Figure 2). Among these, the transcriptional regulation of c-jun and c-fos is well studied and characterized (Abate and Curran, 1990). The transcription of c-fos is induced in response to a diverse spectrum of extracellular stimuli and its promoter is composed of several transcription factor-binding sites, such as a cAMP-response element (CRE), which can drive transcriptional activation in response to elevation of intracellular Ca2+ or cAMP concentrations under stimulation from neurotransmitters and polypeptide hormones (Figure 2; Lucibello et al., 1993; Cavigelli et al., 1995; Tulchinsky, 2000). It also contains a serum-response element (SRE), which can drive transcription in response to growth factors, cytokines, UV irradiation, and other stimuli. SRE is recognized by a dimer composed of serum-response factor (SRF) and Elk-1, the major component of ternary complex factor (TCF) in human cells (Lucibello et al., 1993; Cavigelli et al., 1995; Tulchinsky, 2000; Figure 2). The third major element of c-Fos promoter is the v-Sis-inducible element (SIE) (Wagner et al., 1990). SIE is mostly recognized by homodimers and heterodimers of STAT1 and STAT3, two members of the signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) family (Sadowski et al., 1993). Tyrosine phosphorylation of these factors in the cytoplasm is mediated by janus kinase/tyrosine kinase (JAK/TYKs) and drives their dimerization. The dimerized factor can then translocates to the nucleus, binds the SIE, and participates in promoter activation. Finally, the c-Fos promoter also contains a 12-O-tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate-response element (TRE) (Figure 2; Lucibello et al., 1993; Cavigelli et al., 1995; Tulchinsky, 2000).

Table 1.

The different AP-1-binding sites.

| AP-1-binding sequence | |

|---|---|

| TRE | TGACTCA |

| MAREI | TGCTGACTCAGCA |

| CRE | TGACGTCA |

| MARE II | TGCTGACGTCAGCA |

| ARE | a/gtGACnnnGC |

The main DNA response element is the TPA-responsive element (TRE), but different dimers preferentially bind to elements such as the cAMP-response element (CRE), the MAF-recognition elements (MAREs), and the antioxidant-response elements (AREs).

The c-jun promoter is simpler, being mostly induced through the TRE element that preferentially binds c-Jun/ATF2 heterodimers (Figure 2; Van Dam et al., 1993). Despite its inducible expression, most cell types prior to their stimulation contain basal levels of c-Jun protein. Like the c-fos SRE, the c-jun TRE is constitutively occupied in vivo (Van Dam et al., 1993). Thus, the expression of more than one AP-1 component is under positive and negative AP-1 (auto-)regulation. For example, c-jun and atf3 promoters can be activated by c-Jun/ATF2 and/or ATF2/ATF2 via TRE-binding sites, whereas the atf3 promoter is inhibited by ATF3 (Angel et al., 1988; Hai and Curran, 1991; Van Dam et al., 1993). The c-jun promoter can be inhibited by JunB, c-Jun itself, and c-Fos. This feedback control allows fine-tuned regulation of AP-1 heterodimer activity over longer periods of time (Chiu et al., 1988).

Post-transcriptional Regulation of AP-1 Transcription Factors

Phosphorylation of AP-1 components modulates the dimers transcriptional activities (Karin and Hunter, 1995). Serum and growth factors stimulation induces AP-1 by activating the ERK which then directly phosphorylate c-Jun, Fra-1, and Fra-2 (Figure 2). While phosphorylation of c-Jun by ERK on one serine located next to the C-terminal DNA-binding domain inhibits c-Jun DNA-binding activity, phosphorylation of Fra-1 and Fra-2 enhances their DNA binding in conjunction with c-Jun (Woodgett et al., 1993; Punga et al., 2006).

The induction of AP-1 by pro-inflammatory cytokines and genotoxic stress is mostly mediated by the JNK and p38MAPK pathways (Chang and Karin, 2001; Figure 2). Once activated, JNKs translocate to the nucleus, where they phosphorylate c-Jun on Ser 63/73 and Thr 91/93 and thereby potentiates its ability to activate transcription upon homodimerization or a heterodimerization with c-Fos (Woodgett et al., 1993; Deng and Karin, 1994; Punga et al., 2006). The molecular mechanisms underlying the capacity of JNK to control c-Jun activity involve the modulation of interactions with histone deacetylase complexes, sub-nuclear localization of AP-1 proteins, and related factors required for c-Jun-dependent activity. JNKs also phosphorylate ATF2 on Thr69/71 and potentiate its activity after heterodimerization with c-Jun, leading to its binding to divergent AP-1 sites in the c-jun promoter (Van Dam et al., 1993; Shaulian and Karin, 2002). Transactivation by ATF2 is also potentiated by binding of retinoblastoma (Rb) or E1A, to the DNA-bound ATF2 dimer (Lopez-Bergami et al., 2010). Both E1A and Rb act in concert with phosphorylation of ATF2. Although E1A induces c-jun transcription (Van Dam et al., 1993), it concomitantly represses AP-1 activity through competition for CREB-binding protein (CBP) in a similar manner to the competitive effect of E1A binding on p300 (Offringa et al., 1990; Arany et al., 1994).

The contribution of p38 to AP-1 induction can be mediated by the direct phosphorylation and activation of ATF2 and TCFs (Figure 2; Mendelson et al., 1996; Whitmarsh and Davis, 1996). The PI3K/AKT pathway is activated in response to cytokine receptors and T-cell receptor activation in normal T cells. Akt is a serine/threonine protein kinase activated by PI3K through phosphorylation of Ser473, which acts as a regulator of cell survival and proliferation (Warfel and Kraft, 2015). In addition, glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3), an effector kinase of the PI3K pathway, has the capacity to negatively regulate AP-1 transcriptional activity (Koul et al., 2007; Warfel and Kraft, 2015). GSK3 is a ubiquitously expressed serine/threonine kinase normally active in unstimulated cells. Upon stimulation by growth factors, GSK3 is phosphorylated at Ser9 and Ser21 (for GSK3β and GSK3a, respectively) by Akt and other kinases of the AGC family (protein kinase A, protein kinase G, protein kinase C) thus leading to an important decrease of its activity (Koul et al., 2007; Venkatesan et al., 2010). GSK3 activity is controlled mainly through the PI3K/AKT pathway upon AKT phosphorylation on Ser473 (Koul et al., 2007). This complex network of signaling pathways reveals that a particular stimulus can evoke a specific “spectrum” of AP-1 activity and thereby activate and/or repress distinct subset of AP-1-targetted genes.

The Janus (Dual) Role of AP-1 in Cancer Development

A large amount of studies have shown that AP-1 components play an important role in oncogenesis. c-jun and c-fos were first identified as retrovirus-activated genes with oncogenic potential in avian and mammalian cells (Abate and Curran, 1990; Verma et al., 1990). Chronic exposure to carcinogens can promote tumorigenesis through the activation of a wide array of signaling pathways, ranging from inflammatory to pro-proliferative and survival pathways. Furthermore, environmental or dietary carcinogens have been shown to induce increased AP1 activity (Abate and Curran, 1990; Verma et al., 1990).

Many human cancers exhibit overexpression of Jun family members (Neyns et al., 1996; Langer et al., 2006; Kharman-Biz et al., 2013). Consistent with the idea that c-Jun can promote tumorigenicity, overexpression of this transcription factor is observed in some of the more aggressive CD30-positive lymphomas (Drakos et al., 2007; Mao et al., 2007). In breast cancer, alteration of RB, VEGF, and EGFR pathways has been shown to induce c-Jun overexpression (Kharman-Biz et al., 2013). Interestingly, increased c-Fos expression is associated with poor clinical outcome in osteosarcoma and endometrial carcinoma, while loss of c-Fos expression is associated with tumor progression and adverse outcome in ovarian carcinoma and gastric carcinoma (Tulchinsky, 2000). On the other side, Fra-1 overexpression is associated with the development of thyroid, breast, lung, brain, nasopharyngeal, esophageal, endometrial, prostate, and colon carcinomas, along with glioblastomas and mesotheliomas (Tulchinsky, 2000; Young and Colburn, 2006). The studies are strongly suggesting that the role of Fos family in tumors development depends on the tissue of origin.

Several studies have shown that AP-1 activity is crucial for tumorigenesis, as its inhibition by dominant-negative c-Jun mutants or AP-1 decoys strongly inhibits the growth of various tumor cell lines both in vitro and in vivo (Angel and Karin, 1991; Kajanne et al., 2009; Eckert et al., 2013; Kharman-Biz et al., 2013). These studies have also led to the identification of AP1 target genes involved in carcinogenesis (Eferl and Wagner, 2003; Lopez-Bergami et al., 2010; Nakayama et al., 2012). In addition, chronic exposure to environmental and dietary carcinogens such as cigarette smoke or nicotine or ethanol, activates AP1 activity in mouse brain or epithelial cell lines or neuroblastoma cells (Fried et al., 2001; Jochum et al., 2001; Manna et al., 2006). Interestingly, increase in AP1 activity has been also reported in drug-resistant cancer, suggesting that some chemotherapeutic agents can elicit AP1 activation and favor tumor cell survival by making them refractory to long-term treatments (Malorni et al., 2016; Fan et al., 2017; Liou et al., 2017).

Overexpression of Jun and Fos proteins can also suppress tumor formation (Eferl and Wagner, 2003; Hess et al., 2004; Shaulian, 2010), thus revealing the double-edged activity of AP-1 transcription factors. These dual properties depend on the genetic background of the tumor, its differentiation state, and tumor stage (Eferl and Wagner, 2003; Hess et al., 2004; Shaulian, 2010). Several studies have shown that increased AP-1 activity can lead to apoptosis in human tumor cells but it can also antagonize apoptosis in specific cell types, such as liver tumors (Eferl and Wagner, 2003; Hess et al., 2004; Shaulian, 2010). This dual effect of AP-1 on apoptosis can be further exemplified. Indeed, increased c-Jun activity promotes apoptosis in neuronal cells in vitro (Ham et al., 2000). When the activation of c-Jun is impaired, either in Jnk3-null or JunAA mice, which express a c-Jun insensitive to JNK-mediated activation, neurons are protected from apoptosis (Behrens et al., 1999). In contrast, c-Jun is required for the survival of fetal hepatocytes, which undergo apoptosis in c-Jun-deficient mouse embryos (Eferl et al., 1999; Hasselblatt et al., 2007). The cell-specific consequence of AP-1 activity over apoptosis is likely due to its differential regulation of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic target genes. In neurons, c-Jun regulates the expression of Bim, a pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member that is crucial for neuronal apoptosis. While in T cells, c-Jun regulates the expression of Fas ligand (FasL), which upon binding to the Fas receptor triggers apoptosis (Eferl and Wagner, 2003; Hess et al., 2004; Shaulian, 2010). Bcl-2 family members are also part of the list of anti-apoptotic targets that are regulated by AP-1 (Kirkin et al., 2004). In T cells, Jun members exert a protective signal through the induction of Bcl-3, while in myeloid cells, inactivation of JunB leads to reduced apoptosis with increased expression of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 gene (Kyriakis, 1999; Srivastava et al., 1999; Kirkin et al., 2004) have shown that hepatocytes deficient for c-Jun or JunD are highly sensitive to tumor necrosis factor-α-induced apoptosis, thus suggesting that c-Jun and JunD might regulate genes that protect cells from TNF-α-induced-cell death. Those studies have demonstrated that depending on the type of extracellular stimuli and on the cellular context, activation of AP-1 can have a different outcome on the cell fate. Therefore, the role and function of AP-1 in cancer development should be examined within the context of a complex network of simultaneously triggered signaling pathways.

Regulation of AP-1 During HTLV-1 Infection

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 can infect a variety of cell types in vivo, including T cells, B cells, and macrophages (Jones et al., 2008; Pique and Jones, 2012; Gross and Thoma-Kress, 2016; Rizkallah et al., 2017). The HTLV-1 provirus is detected mainly in CD4+ T cells and to lesser extent in CD8+ T cells (Richardson et al., 1990; Iwahashi et al., 1991; Melamed et al., 2015). This asymmetry in detection may be caused by recruitment of CD4+ T cells and induction of their proliferation following HTLV-1 infection in contrast to a delayed cell death in CD8+ T cells (Sibon et al., 2006; Alais et al., 2015). A subset of HTLV-1-infected individuals will develop ATL after an extended period of time (Matsuoka and Jeang, 2007; Kannian and Green, 2011). Infected cells, however, must initiate proliferation and evade apoptosis as a prelude to immortalization and transformation. Virally encoded oncogenic proteins are known to dysregulate various cellular pathways or processes through the regulation of the activity of target proteins. HTLV-1 transforms T cells via its transactivator Tax, which interferes with pathways regulating cell growth control through activation of various cellular transcription factors (NF-κB, E2F, and AP-1) (Fujii et al., 2000; Peloponese et al., 2006; Journo et al., 2009) and inactivation of p53 (Tabakin-Fix et al., 2006). Since AP-1 has been implicated in transformation of T cells, it has been hypothesized that inappropriate activation of AP-1 could contribute to the dysregulated phenotype of HTLV-1-infected cells or to the development of ATL. Indeed, ATL leukemic cells exhibit increased levels of mRNAs encoding JunD and Fra-2 (Nakayama et al., 2008; Terol et al., 2017) and high levels of AP-1-binding activity (Fujii et al., 2000; Iwai et al., 2001), with in addition, AP-1, more specifically c-Jun/c-Fos heterocomplex, induces HTLV-1 promoter activity and thus participates in HTLV-1 basal transcription (Jeang et al., 1991).

Activation of the AP-1 Pathway by Tax during Acute HTLV-1 Infection

The phosphoprotein Tax is encoded within the pX region of HTLV-1 genome and is a viral regulatory protein. This protein mainly localizes to the nucleus and is a well-known trans-activator of the HTLV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) operating through three 21-bp repeats called Tax-responsive elements (TxREs) (Meertens et al., 2004; Grassmann et al., 2005). Its pleiotropic properties confer a pivotal role for Tax toward viral pathogenicity and immortalization/transformation of infected cells, causing the onset of HTLV-1-associated diseases (Giam and Jeang, 2007; Peloponese et al., 2007). Indeed, the protein is sufficient for immortalizing primary human T cells and rodent fibroblasts as well as inducing tumors in nude mice inoculated with Tax-transformed cells (Grassmann et al., 2005). Furthermore, Tax interferes with important functions, leading to cell cycle dysregulation and promoting in vivo clonal expansion (Giam and Jeang, 2007; Peloponese et al., 2007). Moreover, Tax can alter the expression of cellular proteins involved in cell growth and proliferation such as cytokines (Grassmann et al., 2005; Matsuoka and Jeang, 2010). Importantly, this trans-acting factor also acts as a transcriptional regulator of gene expression by recruiting or modifying the activity of cellular transcription factors (such as CREB protein, SRF, NF-κB, and notably AP-1) through direct or indirect interactions (Grassmann et al., 2005; Matsuoka and Jeang, 2010).

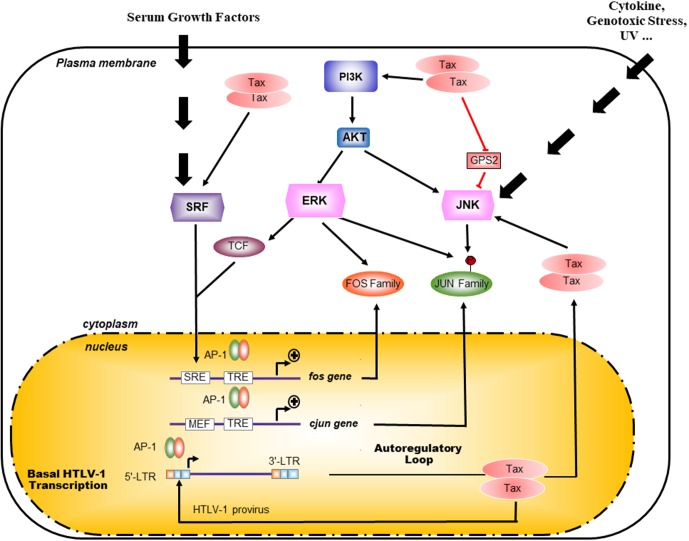

Tax activates the transcription of cellular genes by activating AP-1 DNA binding to promoter elements in T cells (Fujii et al., 2000; Iwai et al., 2001; Figure 3). Thus, activation of AP-1 by Tax is thought to contribute to the deregulated phenotypes and leukemogenesis of T cells infected with HTLV-I. Among these factors, c-Fos, Fra-1, c-Jun, JunB, and JunD genes have been shown to be activated by Tax at the transcriptional level (Fujii et al., 2000; Iwai et al., 2001; Figure 3). Interestingly, exogenous expression of Tax in Jurkat cells induced AP-1-dependent transcription of a reporter gene more efficiently than any combinations of AP-1 proteins (Fujii et al., 2000; Iwai et al., 2001). Thus, the well-known induction of expression of multiple Fos and Jun family members by Tax is known to be essential, but may not be sufficient, for the transcriptional activation of AP-1 sites mediated by Tax (Fujii et al., 2000; Iwai et al., 2001). Since DNA-binding activity and transcriptional activation of AP-1 are regulated at a post-translational level, Tax might be involved in this regulation (Fujii et al., 2000; Iwai et al., 2001). Tax contributes to the high activity of AP-1 in HTLV-1-infected cells through different mechanisms with intricate ramifications in cascade signaling (Figure 3). A constitutive activation of JNK had initially been reported in HTLV-1-infected cells, such as Tax-expressing MT-2 cells and Tax-ATL primary cells. Furthermore, this activity seemed to depend on the status of infection (Xu et al., 1996). Interestingly, Tax is responsible for the constitutive activation of PI3K/Akt by impairing the association between the catalytic (p110) and the regulatory subunit (p85) leading to Akt Ser 473 phosphorylation in HTLV-1-infected cell lines (Peloponese and Jeang, 2006; Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Mechanisms of Tax activation of AP-1 pathway. Pathways upstream of AP-1 are normally activated in response to external stimuli whereas presence of Tax overrides this requirement. Indeed Tax is able to activate the Akt/PI3K pathway as well as the SRF pathways thus activating at the transcription of c-Fos, Fra-1, c-Jun, JunB, and JunD genes. By interacting with the JNK inhibitor G-protein pathway suppressor 2 (GPS2), Tax also participate to the exhibited highly activity of AP-1 in HTLV-1 infected cells through a constitutive activation of JNK (Jin et al., 1997). Interestingly, AP-1 proteins such as c-Jun and c-Fos activate the transcription through the 21 bp repeat in HTLV-1 LTR.

Pathways lying upstream of AP-1 are normally activated in response to external stimuli whereas Tax overrides this requirement (Figure 3). Additionally, the PI3K/Akt-AP-1 pathway had been involved in survival and is likely to be required for the immortalization of HTLV-1-infected cells (Jeong et al., 2005). Indeed, Tax even in the absence of NF-κB signaling is able to activate the Akt/PI3K pathway, which upon inhibition by dominant-negative mutants for Akt or for c-Jun abolishes the proliferation of Tax-transfected cell lines as well as the transformed phenotype (Peloponese and Jeang, 2006). AP-1 sites are Tax-inducible elements in different cellular genes, which promote cell proliferation and are associated with clinical characteristic features of ATL (Figure 3). Among target genes regulated by AP-1-binding sites, Tax activates growth-promoting cytokine genes, such as IL-2, IL-5, IL-13, as well as proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-8 and TNF-a, and further induces the expression of immunosuppressors, like TGF-b1 and proenkephalin (PENK). This deregulation implies different combinations of dimerized AP-1 complex although they have not all been characterized as to their targeted promoters (Brady, 1992; Waldmann, 1996; Yamada et al., 1996; Jeang, 2001; Hall and Fujii, 2005).

Tax does not always activate cellular promoters bearing AP-1-binding site (for example, the collagenase gene) (Hall and Fujii, 2005). Rather, another mechanism, by which promoter could be regulated by Tax through AP1, is linked to the binding of Tax and c-Jun to an overlapping region corresponding to the KIX domain of CBP. This could induce a competition between these two proteins for CBP interaction and lead to the repression of c-Jun transcription activity by Tax (Van Orden et al., 1999; Van Orden and Nyborg, 2000). Although Tax induces the transactivation of the TGF-b1 promoter through AP-1 sites, Tax inhibits TGF-b1 signaling by reducing DNA-binding activity of Smad3 through a Smad3/c-Jun complex, which might be involved in the resistance of TGF-b1-induced growth inhibition observed in ATL cells, an important step in the pathogenesis of ATL (Arnulf et al., 2002). An opposite effect could be imputed to HBZ which could overcome the repressing effect of Tax on TGF-b1 signaling (Zhao et al., 2011). Tax might not solely account for the constitutive activity of AP-1, since a high activity of AP-1 has been detected in primary Tax- leukemia cells of ATL patients (Fujii et al., 2000). These observations indicate that AP-1 is activated in HTLV-1-infected T cells through Tax-dependent and Tax-independent mechanisms.

Hijacking of the AP-1 Signaling Pathway by HBZ

Within its antisense strand, HTLV-1 codes for a bZIP factor, which was appropriately named HBZ (HTLV-I bZIP factor) (Gaudray et al., 2002; Mesnard et al., 2006). HBZ can express under three isoforms: one unspliced form (usHBZ) and two alternatively spliced forms (HBZ-SP1 and HBZ-SP2) (Cavanagh et al., 2006; Murata et al., 2006) with HBZ-SP1 (or sHBZ) being the most abundant spliced variant. sHBZ is a 31-kDa protein with an N-terminal transcriptional activation domain, a central domain involved in nuclear localization, and a C-terminal bZIP domain (Gaudray et al., 2002; Mesnard et al., 2006). Sequence comparison between HBZ bZIP region and several bZIP factors clearly indicates that HBZ possesses a c-Fos-like bZIP domain although its DNA-binding domain lacks the consensus amino acid sequence bb-bN–AA-b(C/S)R-bb thought to be critical for DNA binding. HBZ interacts with all the members of the Jun family (JunB, c-Jun, and JunD), and differently regulates the transcriptional properties of the Jun family (Basbous et al., 2003; Hivin et al., 2005, 2007; Clerc et al., 2009).

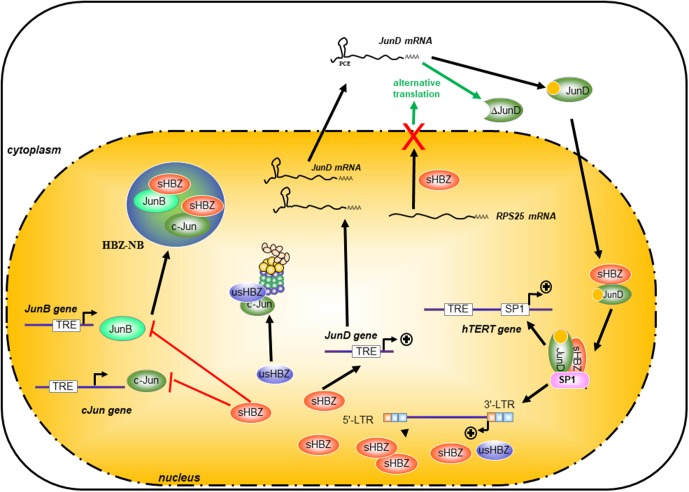

Sequestration of JunB and c-Jun in HBZ Nuclear Bodies Inhibits Their Transcriptional Activities

HTLV-1 basic leucine-zipper factor is a nuclear protein, which not only accumulates in specific nuclear bodies (called here HBZ-NBs) but is targeted to nucleoli (Hivin et al., 2005). Using a fluorescence recovery after photobleaching approach (FRAP) and an EGFP-tagged-HBZ, Hivin et al. (2007) have observed that the deletion of its leucine-zipper domain altered the rate of nuclear flux of HBZ, suggesting that HBZ heterodimerization partners are involved in controlling its own nuclear trafficking. Indeed, HBZ modifies the localization of JunB and targets JunB to the HBZ-NBs. Moreover, the relocalization of JunB into HBZ-NBs inhibits its transcriptional activity (Hivin et al., 2007; Clerc et al., 2009; Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Differential effects of HBZ on the Jun family proteins. HBZ specifically interacted with all three members of the Jun Family (JunB, c-Jun, and JunD), but it regulates differently the transcriptional properties of the Jun family. HBZ dramatically suppressed c-Jun- and JunB-induced transcriptional activation from the AP-1 element by sequestering c-Jun and JunB into HBZ-NB and by decreasing the steady-state level of c-Jun and the stability of c-Jun protein in cells through a proteasome-dependent pathway. It is particularly interesting to note that HBZ has a different and opposite action on JunD expression. HBZ can stimulate the transcription of JunD and by nuclear retention of RPS25, HBZ allows the expression of an alternative isoform of JunD called ΔJunD. Furthermore, HBZ cooperates with JunD and sp1 to enhance transcription of the 3′-LTR and also the human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene (hTERT).

Although HBZ and c-Fos can both interact with c-Jun, they differ greatly in their abilities to activate transcription of AP-1-regulated genes. Indeed, the interaction of HBZ with c-Jun prevents this transcription factor from activating transcription of AP-1-dependent promoters by decreasing its DNA-binding activity (Clerc et al., 2009). The generation of different c-Fos/HBZ chimeras by region swapping indicates that the HBZ DNA-binding motif has an important impact on the transcriptional activity of both transcription factors in the presence of c-Jun (Hivin et al., 2007; Clerc et al., 2009). Indeed, the mutant HBZ-mutMD/DBD, for which specific residues present in the MD and DBD regions of HBZ were substituted for corresponding amino acids of c-Fos, showed a significant in vitro affinity for the AP-1-binding site TRE but remained unable to stimulate promoter activity of the AP-1-dependent collagenase gene in vivo. Like JunB, c-Jun is also relocalized to HBZ-NBs in the presence of HBZ-mutMD/DBD, while this transcription factor is diffusely distributed throughout the nucleus in the presence of HBZ-H14F (a construction in which the bZIP domain of HBZ-mutMD/DBD was replaced by the corresponding ZIP domain of c-Fos), suggesting that HBZ- inhibits c-Jun DNA-binding capacity in vivo mainly by its sequestration to the HBZ-NBs (Hivin et al., 2007; Clerc et al., 2009) (Figure 4 blue circle).

HBZ Promotes the Proteosomal Degradation of c-Jun

HTLV-1 basic leucine-zipper factor can also decrease the stability of c-Jun in cells and promote its degradation (Matsumoto et al., 2005). Indeed, in cells transfected with usHBZ, Matsumoto et al. (2005) observed that treatment with proteasome inhibitors but not with calpain inhibitors prevented the reduction in the steady state of c-Jun, suggesting that this HBZ-mediated reduction in c-Jun abundance could also occur through a proteasome-dependent pathway. It has also been suggested by Isono et al. (2008) that HBZ could act as a tethering factor between the 26S proteasome and c-Jun (Figure 4). However, c-Jun is less degraded by sHBZ (also called HBZ-SP1) than by usHBZ (Isono et al., 2008) and it remains unclear how both isoforms of HBZ could inhibit c-Jun through two different mechanisms.

HBZ Activates the Transcriptional Activity of JunD

It is particularly interesting to note that HBZ has a different and opposite effects on c-Jun- and JunD-dependent transcription. Indeed, these two proteins belong to the same family of transcription factors, but they are very different proteins. In JunD expressing cells, HBZ is diffusely distributed throughout the nucleoplasm, while no HBZ-NBs are formed (Hivin et al., 2007). Interestingly, JunD is the only Jun family member, which can be activated by HBZ (Thebault et al., 2004; Kuhlmann et al., 2007). It is worth noting that the presence of the EQERRE motif in HBZ modulates JunD activity (Hivin et al., 2005). When the HBZ DNA-binding motif is substituted by the c-Fos modulatory domain, HBZ is no longer able to stimulate the transcriptional activity of JunD, although no alteration in the JunD DNA-binding activity is observed (Hivin et al., 2005). It is important to note that the abundance and activity of JunD increase in freshly isolated ATL cells concomitantly with an increase of HBZ expression (Nakayama et al., 2008; Terol et al., 2017). These observations suggest that HBZ modulates its own expression through a positive-feedback loop in resting cells that involves cooperation with JunD (Figure 4). Indeed, in HTLV-1-infected cells, HBZ enhances expression of JunD, which leads to the association of JunD and HBZ to Sp-1 bound to the 3′′-LTR-containing antisense promoter and, ultimately, to the activation of hbz transcription (Gazon et al., 2012).

In association with JunD and Sp-1, HBZ also activates the transcription of the human telomerase catalytic subunit gene (hTERT) (Kuhlmann et al., 2007). Telomerase, a ribonucleoprotein complex that extends telomeres which are essential for protecting chromosomal ends against end–end fusions or degradation (Cong et al., 2002; Brunori et al., 2005; Segal-Bendirdjian and Gilson, 2008). While mouse telomerase (mTERT) is activated in many normal tissues, human cells rarely spontaneously reactivate expression of the telomerase gene, as its expression is tightly regulated (Cong et al., 2002; Brunori et al., 2005; Segal-Bendirdjian and Gilson, 2008). However, 75–85% of cancer cells including ATL cells present an increase in telomerase expression and activity (Uchida et al., 1999; Brunori and Gilson, 2004; Brunori et al., 2005; Shay and Wright, 2011). Human telomerase is composed of a structural RNA component (hTERC), which contains an 11-base sequence complementary to the telomeric single-stranded overhang acting as a template for the synthesis of telomeric DNA. The other main component of the hTERT is its enzymatic reverse transcriptase subunit (Cong et al., 2002; Brunori et al., 2005; Segal-Bendirdjian and Gilson, 2008). Expression of hTERT is regulated mainly at the transcriptional level. The proximal 180 bp of the hTERT promoter, which does not contain any AP-1-binding site, is important for maintaining basal transcriptional activity and is thought to be the essential component for its regulation. Interestingly, Kuhlmann et al. (2007) have observed an increase in hTERT transcripts in cells co-expressing HBZ and JunD. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays revealed that HBZ/JunD heterodimers interact with Sp1 and that activation of hTERT transcription by this trimer is mediated through Sp-1-binding sites present in the core region of the hTERT promoter (Kuhlmann et al., 2007).

We recently uncovered an additional mechanism used by HBZ to turn JunD from a growth suppressor to a tumor promoter (Terol et al., 2017). JunD is an intronless gene and produces two predominant isoforms by alternative initiation of translation, a 39-kDa protein (JunD-FL) through initiation from the first AUG codon and a shorter, 34-kDa JunD protein (ΔJunD) through the use of the second in-frame AUG codon (Hirai et al., 1989; Berger and Shaul, 1994; Short and Pfarr, 2002). Several studies indicated that JunD-FL and ΔJunD are differentially regulated through interactions with other nuclear proteins (Hirai et al., 1989; Berger and Shaul, 1994; Short and Pfarr, 2002). For example, menin, the product of the tumor-suppressor MEN-1 gene, represses JunD-FL transcriptional activity by interacting through its first 48 amino acids (Agarwal et al., 1999; Yazgan and Pfarr, 2001). Loss of menin expression or lost the ability of menin to bind JunD confers JunD with growth-promoting capabilities (Agarwal et al., 2003). ΔJunD does not bind menin, and its transcriptional activity is unaffected by menin overexpression (Yazgan and Pfarr, 2001). In addition, JNK binds and activates JunD-FL more efficiently than ΔJunD, even though both JunD isoforms contain a JNK-docking domain and three JNK phosphorylation target sites. It is interesting to note that freshly isolated ATL cells and HBZ-expressing T lymphocytes express both JunD isoforms (Yazgan and Pfarr, 2002).

JunD mRNA contains a third functional out-of-frame ORF (uORFs) positioned between the ATG of JunD-FL and ATG of ΔJunD (Short and Pfarr, 2002). Translation of downstream ORFs by uORF appears to be a common translational regulatory mechanism, as uORFs are present in two-third of mRNAs encoding oncoproteins and proteins that regulate important cellular processes. Alteration of protein expression levels by disruption or creation of uORF has been associated with the development of several human disease such as Alzheimer’s disease, acute myeloid leukemia, and breast cancer (Short and Pfarr, 2002; Zhou and Song, 2006; Wethmar et al., 2010; Barbosa et al., 2013). HBZ relieves uORF translational control by reducing the cellular abundance of RPS25, a ribosomal protein known to play a key role in several alternative translation mechanisms (Nishiyama et al., 2007). Using an immortalized fibroblast cell line model, we found that ΔJunD exhibits growth-promoting and -transforming activities that are enhanced in presence of HBZ (Terol et al., 2017). In summary, it has been proposed that HBZ/JunD heterodimers induce down-regulation of lymphocyte activation and viral transcription to favor viral latency and persistence of the infected cells. Future studies will aim to clarify how HBZ/JunD and/or HBZ/ΔJunD coordinately drive cell fate toward cellular transformation.

Perspectives and Conclusion

Activating protein-1 family members have both overlapping and unique roles, and the transcriptional activity of the AP-1 dimer functions in a tissue-specific fashion (Shaulian, 2010). With respect to this important fact, recent studies have included the analysis of expression and/or activity of all Jun and Fos family members. Thus, it has been demonstrated that malignant transformation and tumor progression is accompanied by a cell-type-specific shift in AP-1 dimer composition (Verma et al., 1990; Radler-Pohl et al., 1993; Karin et al., 1997; Tulchinsky, 2000; Shaulian and Karin, 2002; Eferl and Wagner, 2003; Milde-Langosch, 2005; Hernandez et al., 2008; Shaulian, 2010). Those studies support a model, in which a shift in the expression pattern of the Fos family members is a crucial step in carcinogenesis and/or tumor progression (Tulchinsky, 2000; Milde-Langosch, 2005). Indeed, while uninfected CD4+ T-lymphocytes express mainly c-Jun and c-Fos proteins, ATL-leukemic cells are expressing JunD and Fra-2 (Nakayama et al., 2008; Terol et al., 2017). Due to their lack of a trans-activating domain, it has been suggested that Fra-1 and Fra-2 might exert anti-tumor effect and inhibit tumor cell growth. Yet, recent studies point to a positive effect of Fra-1, and partly Fra-2, on tumor growth (Young and Colburn, 2006; Milde-Langosch et al., 2008; Nakayama et al., 2008; Davies et al., 2011; Higuchi et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014; Gupta et al., 2015).

Indeed, gene substitution experiments in mice have shown that growth retardation and osteoporosis observed in c-Fos null-mice were rescued by Fra-1 overexpression, although Fra-1 failed to induce expression of c-Fos target genes, such as MMP13 and vimentin (Young and Colburn, 2006). This observation is in line with results obtained in various cancer cell types, in which Fra-1 alters the biological behavior of the cells without directly activating AP-1-responsive promoters (Zerbini et al., 2003; Young and Colburn, 2006). Surprisingly, in most of the clinical tumor samples analyzed so far, Fra-1 expression is lower than in normal cells, and the protein is poorly phosphorylated (Zerbini et al., 2003; Young and Colburn, 2006). These observations raised several interesting questions on the true role of Fra-1 in oncogenesis and tumor progression. Indeed, whether the low level Fra-1 expression is due to tumor heterogeneity and if expression Fra-1 in specific clones within the tumors have a similar effect to what is seen in experimental systems and contributes to local invasion and metastasis should be further studied. In contrast to the bulk of data available on the function of c-Fos and Fra-1 in carcinogenesis, far less is known on the role of other Fos family members (FosB, FosB2, deltaFosB2, and Fra-2), which are often found expressed in high levels in cancer tissues. Further study of the role of all Fos proteins in carcinogenesis will be of great importance.

Author Contributions

J-MP and HG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. HG, BB, J-MM, and J-MP wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (Equipe FRM DEQ20161136701) and the Ligue Contre le Cancer, Comité Hérault.

References

- Abate C., Curran T. (1990). Encounters with Fos and Jun on the road to AP-1. Semin. Cancer Biol. 1 19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S. K., Guru S. C., Heppner C., Erdos M. R., Collins R. M., Park S. Y. (1999). Menin interacts with the AP1 transcription factor JunD and represses JunD-activated transcription. Cell 96 143–152. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80967-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S. K., Novotny E. A., Crabtree J. S., Weitzman J. B., Yaniv M., Burns A. L., et al. (2003). Transcription factor JunD, deprived of menin, switches from growth suppressor to growth promoter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 10770–10775. 10.1073/pnas.1834524100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alais S., Mahieux R., Dutartre H. (2015). Viral source-independent high susceptibility of dendritic cells to human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 infection compared to that of T Lymphocytes. J. Virol. 89 10580–10590. 10.1128/JVI.01799-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel P., Hattori K., Smeal T., Karin M. (1988). The jun proto-oncogene is positively autoregulated by its product, Jun/AP-1. Cell 55 875–885. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90143-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel P., Karin M. (1991). The role of Jun, Fos and the AP-1 complex in cell-proliferation and transformation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1072 129–157. 10.1016/0304-419X(91)90011-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arany Z., Sellers W. R., Livingston D. M., Eckner R. (1994). E1A-associated p300 and CREB-associated CBP belong to a conserved family of coactivators. Cell 77 799–800. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90127-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnulf B., Villemain A., Nicot C., Mordelet E., Charneau P., Kersual J., et al. (2002). Human T-cell lymphotropic virus oncoprotein Tax represses TGF-beta 1 signaling in human T cells via c-Jun activation: a potential mechanism of HTLV-I leukemogenesis. Blood 100 4129–4138. 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa C., Peixeiro I., Romão L. (2013). Gene expression regulation by upstream open reading frames and human disease. PLOS Genet. 9:e1003529. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basbous J., Arpin C., Gaudray G., Piechaczyk M., Devaux C., Mesnard J. M. (2003). The HBZ factor of human T-cell leukemia virus type I dimerizes with transcription factors JunB and c-Jun and modulates their transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278 43620–43627. 10.1074/jbc.M307275200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens A., Sibilia M., Wagner E. F. (1999). Amino-terminal phosphorylation of c-Jun regulates stress-induced apoptosis and cellular proliferation. Nat. Genet. 21 326–329. 10.1038/6854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger I., Shaul Y. (1994). The human junD gene is positively and selectively autoregulated. DNA Cell Biol. 13 249–255. 10.1089/dna.1994.13.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady J. N. (1992). Extracellular Tax1 protein stimulates NF-kB and expression of NF-kB-responsive Ig kappa and TNF beta genes in lymphoid cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 8 724–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunori M., Gilson E. (2004). The opposite roles of telomerase during initiation and progression of cancers. J. Soc. Biol. 198 105–111. 10.1051/jbio/2004198020105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunori M., Luciano P., Gilson E., Geli V. (2005). The telomerase cycle: normal and pathological aspects. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 83 244–257. 10.1007/s00109-004-0616-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh M. H., Landry S., Audet B., Arpin-Andre C., Hivin P., Pare M. E. (2006). HTLV-I antisense transcripts initiating in the 3’LTR are alternatively spliced and polyadenylated. Retrovirology 3:15. 10.1186/1742-4690-3-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavigelli M., Dolfi F., Claret F. X., Karin M. (1995). Induction of c-fos expression through JNK-mediated TCF/Elk-1 phosphorylation. EMBO J. 14 5957–5964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J. K., Greene W. C. (2012). Dynamic roles for NF-kappaB in HTLV-I and HIV-1 retroviral pathogenesis. Immunol. Rev. 246 286–310. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01094.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L., Karin M. (2001). Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature 410 37–40. 10.1038/35065000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu R., Boyle W. J., Meek J., Smeal T., Hunter T., Karin M. (1988). The c-Fos protein interacts with c-Jun/AP-1 to stimulate transcription of AP-1 responsive genes. Cell 54 541–552. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90076-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc I., Hivin P., Rubbo P. A., Lemasson I., Barbeau B., Mesnard J. M. (2009). Propensity for HBZ-SP1 isoform of HTLV-I to inhibit c-Jun activity correlates with sequestration of c-Jun into nuclear bodies rather than inhibition of its DNA-binding activity. Virology 391 195–202. 10.1016/j.virol.2009.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong Y.-S., Wright W. E., Shay J. W. (2002). Human telomerase and its regulation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66 407–425. 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.407-425.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran T., Franza B. R. (1988). Fos and jun: the AP-1 connection. Cell 55 395–397. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90024-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J. S., Klein D. C., Carter D. A. (2011). Selective genomic targeting by FRA-2/FOSL2 transcription factor: regulation of the Rgs4 gene is mediated by a variant activator protein 1 (AP-1) promoter sequence/CREB-binding protein (CBP) mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 286 15227–15239. 10.1074/jbc.M110.201996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng T., Karin M. (1994). c-Fos transcriptional activity stimulated by H-Ras-activated protein kinase distinct from JNK and ERK. Nature 371 171–175. 10.1038/371171a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drakos E., Leventaki V., Schlette E. J., Jones D., Lin P., Medeiros L. J., et al. (2007). c-Jun expression and activation are restricted to CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 31 447–453. 10.1097/01.pas.0000213412.25935.e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert R. L., Adhikary G., Young C. A., Jans R., Crish J. F., Xu W., et al. (2013). AP1 transcription factors in epidermal differentiation and skin cancer. J. Skin Cancer 2013:537028. 10.1155/2013/537028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eferl R., Sibilia M., Hilberg F., Fuchsbichler A., Kufferath I., Guertl B., et al. (1999). Functions of c-Jun in Liver and Heart Development. J. Cell Biol. 145 1049–1061. 10.1083/jcb.145.5.1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eferl R., Wagner E. F. (2003). AP-1: a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3 859–868. 10.1038/nrc1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan F., Bashari M. H., Morelli E., Tonon G., Malvestiti S., Vallet S., et al. (2017). The AP-1 transcription factor JunB is essential for multiple myeloma cell proliferation and drug resistance in the bone marrow microenvironment. Leukemia 31 1570–1581. 10.1038/leu.2016.358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried U., Kotarsky K., Alling C. (2001). Chronic ethanol exposure enhances activating protein-1 transcriptional activity in human neuroblastoma cells. Alcohol 24 189–195. 10.1016/S0741-8329(01)00151-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii M., Iwai K., Oie M., Fukushi M., Yamamoto N., Kannagi M., et al. (2000). Activation of oncogenic transcription factor AP-1 in T cells infected with human T cell leukemia virus type 1. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 16 1603–1606. 10.1089/08892220050193029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudray G., Gachon F., Basbous J., Biard-Piechaczyk M., Devaux C., Mesnard J. M. (2002). The complementary strand of the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 RNA genome encodes a bZIP transcription factor that down-regulates viral transcription. J. Virol. 76 12813–12822. 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12813-12822.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazon H., Lemasson I., Polakowski N., Cesaire R., Matsuoka M., Barbeau B., et al. (2012). Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) bZIP factor requires cellular transcription factor JunD to upregulate HTLV-1 antisense transcription from the 3’ long terminal repeat. J. Virol. 86 9070–9078. 10.1128/JVI.00661-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessain A., Cassar O. (2012). Epidemiological aspects and world distribution of HTLV-1 infection. Front. Microbiol. 3:388. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giam C. Z., Jeang K. T. (2007). HTLV-1 Tax and adult T-cell leukemia. Front. Biosci. 12 1496–1507. 10.2741/2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassmann R., Aboud M., Jeang K. T. (2005). Molecular mechanisms of cellular transformation by HTLV-1 Tax. Oncogene 24 5976–5985. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross C., Thoma-Kress A. K. (2016). Molecular mechanisms of HTLV-1 Cell-to-Cell transmission. Viruses 8:74. 10.3390/v8030074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Kumar P., Kaur H., Sharma N., Saluja D., Bharti A. C., et al. (2015). Selective participation of c-Jun with Fra-2/c-Fos promotes aggressive tumor phenotypes and poor prognosis in tongue cancer. Sci. Rep. 5:16811. 10.1038/srep16811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai T., Curran T. (1991). Cross-family dimerization of transcription factors Fos/Jun and ATF/CREB alters DNA binding specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 3720–3724. 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W. W., Fujii M. (2005). Deregulation of cell-signaling pathways in HTLV-1 infection. Oncogene 24 5965–5975. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham J., Eilers A., Whitfield J., Neame S. J., Shah B. (2000). c-Jun and the transcriptional control of neuronal apoptosis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 60 1015–1021. 10.1016/S0006-2952(00)00372-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselblatt P., Rath M., Komnenovic V., Zatloukal K., Wagner E. F. (2007). Hepatocyte survival in acute hepatitis is due to c-Jun/AP-1-dependent expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 17105–17110. 10.1073/pnas.0706272104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez J. M., Floyd D. H., Weilbaecher K. N., Green P. L., Boris-Lawrie K. (2008). Multiple facets of junD gene expression are atypical among AP-1 family members. Oncogene 27 4757–4767. 10.1038/onc.2008.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess J., Angel P., Schorpp-Kistner M. (2004). AP-1 subunits: quarrel and harmony among siblings. J. Cell Sci. 117 5965–5973. 10.1242/jcs.01589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi T., Nakayama T., Arao T., Nishio K., Yoshie O. (2013). SOX4 is a direct target gene of FRA-2 and induces expression of HDAC8 in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Blood 121 3640–3649. 10.1182/blood-2012-07-441022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai S. I., Ryseck R. P., Mechta F., Bravo R., Yaniv M. (1989). Characterization of junD: a new member of the jun proto-oncogene family. EMBO J. 8 1433–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hivin P., Basbous J., Raymond F., Henaff D., Arpin-Andre C., Robert-Hebmann V., et al. (2007). The HBZ-SP1 isoform of human T-cell leukemia virus type I represses JunB activity by sequestration into nuclear bodies. Retrovirology 4:14. 10.1186/1742-4690-4-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hivin P., Frederic M., Arpin-Andre C., Basbous J., Gay B., Thebault S., et al. (2005). Nuclear localization of HTLV-I bZIP factor (HBZ) is mediated by three distinct motifs. J. Cell Sci. 118 1355–1362. 10.1242/jcs.01727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isono O., Ohshima T., Saeki Y., Matsumoto J., Hijikata M., Tanaka K., et al. (2008). Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 HBZ protein bypasses the targeting function of ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 283 34273–34282. 10.1074/jbc.M802527200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwahashi M., Nakahara K., Takeshita T., Shimotakahara S., Uozumi K., Hanada S. (1991). Surface phenotypic diversity of CD4 or CD8 in ATL. Rinsho Ketsueki 32 142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai K., Mori N., Oie M., Yamamoto N., Fujii M. (2001). Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 tax protein activates transcription through AP-1 site by inducing DNA binding activity in T cells. Virology 279 38–46. 10.1006/viro.2000.0669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanaga M., Watanabe T., Utsunomiya A., Okayama A., Uchimaru K., Koh K. R., et al. (2010). Human T-cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-1) proviral load and disease progression in asymptomatic HTLV-1 carriers: a nationwide prospective study in Japan. Blood 116 1211–1219. 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeang K. T. (2001). Functional activities of the human T-cell leukemia virus type I Tax oncoprotein: cellular signaling through NF-kappa B. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 12 207–217. 10.1016/S1359-6101(00)00028-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeang K. T., Chiu R., Santos E., Kim S. J. (1991). Induction of the HTLV-I LTR by Jun occurs through the Tax-responsive 21-bp elements. Virology 181 218–227. 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90487-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S. J., Pise-Masison C. A., Radonovich M. F., Park H. U., Brady J. N. (2005). Activated AKT regulates NF-kappaB activation, p53 inhibition and cell survival in HTLV-1-transformed cells. Oncogene 24 6719–6728. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin D. Y., Teramoto H., Giam C. Z., Chun R. F., Gutkind J. S., Jeang K. T. (1997). A human suppressor of c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 activation by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 272 25816–25823. 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jochum W., Passegue E., Wagner E. F. (2001). AP-1 in mouse development and tumorigenesis. Oncogene 20 2401–2412. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K. S., Petrow-Sadowski C., Huang Y. K., Bertolette D. C., Ruscetti F. W. (2008). Cell-free HTLV-1 infects dendritic cells leading to transmission and transformation of CD4(+) T cells. Nat. Med. 14 429–436. 10.1038/nm1745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Journo C., Douceron E., Mahieux R. (2009). HTLV gene regulation: because size matters, transcription is not enough. Future Microbiol. 4 425–440. 10.2217/fmb.09.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajanne R., Miettinen P., Tenhunen M., Leppa S. (2009). Transcription factor AP-1 promotes growth and radioresistance in prostate cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 35 1175–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannian P., Green P. L. (2011). Human T lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1): molecular biology and oncogenesis. Viruses 2 2037–2077. 10.3390/v2092037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M. (1995). The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 270 16483–16486. 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M., Hunter T. (1995). Transcriptional control by protein phosphorylation: signal transmission from the cell surface to the nucleus. Curr. Biol. 5 747–757. 10.1016/S0960-9822(95)00151-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M., Liu Z., Zandi E. (1997). AP-1 function and regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9 240–246. 10.1016/S0955-0674(97)80068-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka K., Nagata Y., Kitanaka A., Shiraishi Y., Shimamura T., Yasunaga J., et al. (2015). Integrated molecular analysis of adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma. Nat. Genet. 47 1304–1315. 10.1038/ng.3415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharman-Biz A., Gao H., Ghiasvand R., Zhao C., Zendehdel K., Dahlman-Wright K. (2013). Expression of activator protein-1 (AP-1) family members in breast cancer. BMC Cancer 13:441. 10.1186/1471-2407-13-441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkin V., Joos S., Zörnig M. (2004). The role of Bcl-2 family members in tumorigenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1644 229–249. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2003.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogure Y., Kataoka K. (2017). Genetic alterations in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 108 1719–1725. 10.1111/cas.13303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koul D., Shen R., Shishodia S., Takada Y., Bhat K. P., Reddy S. A., et al. (2007). PTEN down regulates AP-1 and targets c-fos in human glioma cells via PI3-kinase/Akt pathway. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 300 77–87. 10.1007/s11010-006-9371-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann A. S., Villaudy J., Gazzolo L., Castellazzi M., Mesnard J. M., Duc Dodon M. (2007). HTLV-1 HBZ cooperates with JunD to enhance transcription of the human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene (hTERT). Retrovirology 4:92. 10.1186/1742-4690-4-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis J. M. (1999). Activation of the AP-1 transcription factor by inflammatory cytokines of the TNF family. Gene Expr. 7 217–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer S., Singer C. F., Hudelist G., Dampier B., Kaserer K., Vinatzer U., et al. (2006). Jun and Fos family protein expression in human breast cancer: correlation of protein expression and clinicopathological parameters. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 27 345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J. T., Lin C. S., Liao Y. C., Ho L. J., Yang S. P., Lai J. H. (2017). JNK/AP-1 activation contributes to tetrandrine resistance in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 38 1171–1183. 10.1038/aps.2017.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Bergami P., Lau E., Ronai Z. E. (2010). Emerging roles of ATF2 and the dynamic AP1 network in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10 65–76. 10.1038/nrc2681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucibello F. C., Brusselbach S., Sewing A., Muller R. (1993). Suppression of the growth factor-mediated induction of c-fos and down-modulation of AP-1-binding activity are not required for cellular senescence. Oncogene 8 1667–1672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malorni L., Giuliano M., Migliaccio I., Wang T., Creighton C. J., Lupien M., et al. (2016). Blockade of AP-1 potentiates endocrine therapy and overcomes resistance. Mol. Cancer Res. 14 470–481. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-15-0423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna S. K., Rangasamy T., Wise K., Sarkar S., Shishodia S., Biswal S., et al. (2006). Long term environmental tobacco smoke activates nuclear transcription factor-kappa B, activator protein-1, and stress responsive kinases in mouse brain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 71 1602–1609. 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X., Orchard G., Russell-Jones R., Whittaker S. (2007). Abnormal activator protein 1 transcription factor expression in CD30-positive cutaneous large-cell lymphomas. Br. J. Dermatol. 157 914–921. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08150.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto J., Ohshima T., Isono O., Shimotohno K. (2005). HTLV-1 HBZ suppresses AP-1 activity by impairing both the DNA-binding ability and the stability of c-Jun protein. Oncogene 24 1001–1010. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M., Green P. L. (2009). The HBZ gene, a key player in HTLV-1 pathogenesis. Retrovirology 6:71. 10.1186/1742-4690-6-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M., Jeang K. T. (2007). Human T-cell leukaemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) infectivity and cellular transformation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7 270–280. 10.1038/nrc2111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M., Jeang K. T. (2010). Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) and leukemic transformation: viral infectivity, Tax, HBZ and therapy. Oncogene 30 1379–1389. 10.1038/onc.2010.537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M., Tamiya S., Takemoto S., Yamaguchi K., Takatsuki K. (1997). HTLV-I provirus in the clinical subtypes of ATL. Leukemia 11(Suppl. 3), 67–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meertens L., Chevalier S., Weil R., Gessain A., Mahieux R. (2004). A 10-amino acid domain within human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 and type 2 tax protein sequences is responsible for their divergent subcellular distribution. J. Biol. Chem. 279 43307–43320. 10.1074/jbc.M400497200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed A., Laydon D. J., Al Khatib H., Rowan A. G., Taylor G. P., Bangham C. R. (2015). HTLV-1 drives vigorous clonal expansion of infected CD8(+) T cells in natural infection. Retrovirology 12:91. 10.1186/s12977-015-0221-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson K. G., Contois L. R., Tevosian S. G., Davis R. J., Paulson K. E. (1996). Independent regulation of JNK/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases by metabolic oxidative stress in the liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 12908–12913. 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesnard J. M., Barbeau B., Devaux C. (2006). HBZ, a new important player in the mystery of adult T-cell leukemia. Blood 108 3979–3982. 10.1182/blood-2006-03-007732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milde-Langosch K. (2005). The Fos family of transcription factors and their role in tumourigenesis. Eur. J. Cancer 41 2449–2461. 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milde-Langosch K., Janke S., Wagner I., Schroder C., Streichert T., Bamberger A. M., et al. (2008). Role of Fra-2 in breast cancer: influence on tumor cell invasion and motility. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 107 337–347. 10.1007/s10549-007-9559-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K., Hayashibara T., Sugahara K., Uemura A., Yamaguchi T., Harasawa H., et al. (2006). A novel alternative splicing isoform of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 bZIP factor (HBZ-SI) targets distinct subnuclear localization. J. Virol. 80 2495–2505. 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2495-2505.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musti A. M., Treier M., Peverali F. A., Bohmann D. (1996). Differential regulation of c-Jun and JunD by ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. Biol. Chem. 377 619–624. 10.1515/bchm3.1996.377.10.619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama T., Hieshima K., Arao T., Jin Z., Nagakubo D., Shirakawa A. K., et al. (2008). Aberrant expression of Fra-2 promotes CCR4 expression and cell proliferation in adult T-cell leukemia. Oncogene 27 3221–3232. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama T., Higuchi T., Oiso N., Kawada A., Yoshie O. (2012). Expression and function of FRA2/JUND in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Anticancer Res. 32 1367–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyns B., Katesuwanasing Vermeij J., Bourgain C., Vandamme B., Amfo K. (1996). Expression of the jun family of genes in human ovarian cancer and normal ovarian surface epithelium. Oncogene 12 1247–1257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama T., Yamamoto H., Uchiumi T., Nakashima N. (2007). Eukaryotic ribosomal protein RPS25 interacts with the conserved loop region in a dicistroviral intergenic internal ribosome entry site. Nucleic Acids Res. 35 1514–1521. 10.1093/nar/gkl1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offringa R., Gebel S., Van Dam H., Timmers M., Smits A., Zwart R., et al. (1990). A novel function of the transforming domain of E1a: repression of AP-1 activity. Cell 62 527–538. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90017-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olindo S., Lezin A., Cabre P., Merle H., Saint-Vil M., Edimonana Kaptue M., et al. (2005). HTLV-1 proviral load in peripheral blood mononuclear cells quantified in 100 HAM/TSP patients: a marker of disease progression. J. Neurol. Sci. 237 53–59. 10.1016/j.jns.2005.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peloponese J. M., Jr., Jeang K. T. (2006). Role for Akt/protein kinase B and activator protein-1 in cellular proliferation induced by the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 tax oncoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 281 8927–8938. 10.1074/jbc.M510598200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peloponese J. M., Jr., Kinjo T., Jeang K. T. (2007). Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax and cellular transformation. Int. J. Hematol. 86 101–106. 10.1532/IJH97.07087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peloponese J. M., Yeung M. L., Jeang K. T. (2006). Modulation of nuclear factor-kappaB by human T cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax protein: implications for oncogenesis and inflammation. Immunol. Res. 34 1–12. 10.1385/IR:34:1:1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pique C., Jones K. S. (2012). Pathways of cell-cell transmission of HTLV-1. Front. Microbiol. 3:378 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punga T., Bengoechea-Alonso M. T., Ericsson J. (2006). Phosphorylation and ubiquitination of the transcription factor sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 in response to DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 281 25278–25286. 10.1074/jbc.M604983200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radler-Pohl A., Gebel S., Sachsenmaier C., Konig H., Kramer M., Oehler T., et al. (1993). The activation and activity control of AP-1 (fos/jun). Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 684 127–148. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb32277.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J. H., Edwards A. J., Cruickshank J. K., Rudge P., Dalgleish A. G. (1990). In vivo cellular tropism of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1. J. Virol. 64 5682–5687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizkallah G., Alais S., Futsch N., Tanaka Y., Journo C., Mahieux R., et al. (2017). Dendritic cell maturation, but not type I interferon exposure, restricts infection by HTLV-1, and viral transmission to T-cells. PLOS Pathog. 13:e1006353. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosin O., Koch C., Schmitt I., Semmes O. J., Jeang K. T., Grassmann R. (1998). A human T-cell leukemia virus Tax variant incapable of activating NF-kappaB retains its immortalizing potential for primary T-lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 273 6698–6703. 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder K., Nathans D. (1988). Induction of protooncogene c-jun by serum growth factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85 8464–8467. 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski H. B., Shuai K., Darnell J. E., Jr., Gilman M. Z. (1993). A common nuclear signal transduction pathway activated by growth factor and cytokine receptors. Science 261 1739–1744. 10.1126/science.8397445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal-Bendirdjian E., Gilson E. (2008). Telomeres and telomerase: from basic research to clinical applications. Biochimie 90 1–4. 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaulian E. (2010). AP-1–The Jun proteins: Oncogenes or tumor suppressors in disguise? Cell Signal 22 894–899. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaulian E., Karin M. (2002). AP-1 as a regulator of cell life and death. Nat. Cell Biol. 4 E131–E136. 10.1038/ncb0502-e131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay J. W., Wright W. E. (2011). Role of telomeres and telomerase in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 21 349–353. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short J. D., Pfarr C. M. (2002). Translational regulation of the JunD messenger RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 277 32697–32705. 10.1074/jbc.M204553200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibon D., Gabet A. S., Zandecki M., Pinatel C., Thete J., Delfau-Larue M. H., et al. (2006). HTLV-1 propels untransformed CD4 lymphocytes into the cell cycle while protecting CD8 cells from death. J. Clin. Invest. 116 974–983. 10.1172/JCI27198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda S., Li H. C., Tajima K. (2011). Ethnoepidemiology of HTLV-1 related diseases: ethnic determinants of HTLV-1 susceptibility and its worldwide dispersal. Cancer Sci. 102 295–301. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01820.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S., Weitzmann M. N., Cenci S., Ross F. P., Adler S., Pacifici R. (1999). Estrogen decreases TNF gene expression by blocking JNK activity and the resulting production of c-Jun and JunD. J. Clin. Invest. 104 503–513. 10.1172/JCI7094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabakin-Fix Y., Azran I., Schavinky-Khrapunsky Y., Levy O., Aboud M. (2006). Functional inactivation of p53 by human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax protein: mechanisms and clinical implications. Carcinogenesis 27 673–681. 10.1093/carcin/bgi274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamiya S., Matsuoka M., Etoh K., Watanabe T., Kamihira S., Yamaguchi K., et al. (1996). Two types of defective human T-lymphotropic virus type I provirus in adult T-cell leukemia. Blood 88 3065–3073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terol M., Gazon H., Lemasson I., Duc-Dodon M., Barbeau B., Cesaire R., et al. (2017). HBZ-mediated shift of JunD from growth suppressor to tumor promoter in leukemic cells by inhibition of ribosomal protein S25 expression. Leukemia 31 2235–2243. 10.1038/leu.2017.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thebault S., Basbous J., Hivin P., Devaux C., Mesnard J. M. (2004). HBZ interacts with JunD and stimulates its transcriptional activity. FEBS Lett. 562 165–170. 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00225-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulchinsky E. (2000). Fos family members: regulation, structure and role in oncogenic transformation. Histol. Histopathol. 15 921–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N., Otsuka T., Arima F., Shigematsu H., Fukuyama T., Maeda M., et al. (1999). Correlation of telomerase activity with development and progression of adult T-cell leukemia. Leuk. Res. 23 311–316. 10.1016/S0145-2126(98)00170-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam H., Duyndam M., Rottier R., Bosch A., De Vries-Smits L., Herrlich P., et al. (1993). Heterodimer formation of cJun and ATF-2 is responsible for induction of c-jun by the 243 amino acid adenovirus E1A protein. EMBO J. 12 479–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden K., Nyborg J. K. (2000). Insight into the tumor suppressor function of CBP through the viral oncoprotein tax. Gene Expr. 9 29–36. 10.3727/000000001783992678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden K., Yan J. P., Ulloa A., Nyborg J. K. (1999). Binding of the human T-cell leukemia virus Tax protein to the coactivator CBP interferes with CBP-mediated transcriptional control. Oncogene 18 3766–3772. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan B., Valente A. J., Prabhu S. D., Shanmugam P., Delafontaine P., Chandrasekar B. (2010). EMMPRIN activates multiple transcription factors in cardiomyocytes, and induces interleukin-18 expression via Rac1-dependent PI3K/Akt/IKK/NF-kappaB andMKK7/JNK/AP-1 signaling. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 49 655–663. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma I. M., Ransone L. J., Visvader J., Sassone-Corsi P., Lamph W. W. (1990). fos-jun conspiracy: implications for the cell. Ciba Found. Symp. 150 128–137;discussion 137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner B. J., Hayes T. E., Hoban C. J., Cochran B. H. (1990). The SIF binding element confers sis/PDGF inducibility onto the c-fos promoter. EMBO J. 9 4477–4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann T. A. (1996). The promiscuous IL-2/IL-15 receptor: a target for immunotherapy of HTLV-I-associated disorders. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 13(Suppl. 1), S179–S185. 10.1097/00042560-199600001-00027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Sun D., Wang Y., Ren F., Pang S., Wang D., et al. (2014). FOSL2 positively regulates TGF-beta1 signalling in non-small cell lung cancer. PLOS ONE 9:e112150. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warfel N. A., Kraft A. S. (2015). PIM kinase (and Akt) biology and signaling in tumors. Pharmacol. Ther. 151 41–49. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wethmar K., Smink J. J., Leutz A. (2010). Upstream open reading frames: molecular switches in (patho)physiology. Bioessays 32 885–893. 10.1002/bies.201000037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh A. J., Davis R. J. (1996). Transcription factor AP-1 regulation by mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 74 589–607. 10.1007/s001090050063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgett J. R., Pulverer B. J., Nikolakaki E., Plyte S., Hughes K., Franklin C. C., et al. (1993). Regulation of jun/AP-1 oncoproteins by protein phosphorylation. Adv. Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 28 261–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Heidenreich O., Kitajima I., Mcguire K., Li Q., Su B., et al. (1996). Constitutively activated JNK is associated with HTLV-1 mediated tumorigenesis. Oncogene 13 135–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y., Ohmoto Y., Hata T., Yamamura M., Murata K., Tsukasaki K., et al. (1996). Features of the cytokines secreted by adult T cell leukemia (ATL) cells. Leuk. Lymphoma 21 443–447. 10.3109/10428199609093442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazgan O., Pfarr C. M. (2001). Differential binding of the Menin tumor suppressor protein to JunD isoforms. Cancer Res. 61 916–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazgan O., Pfarr C. M. (2002). Regulation of two JunD isoforms by Jun N-terminal kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 277 29710–29718. 10.1074/jbc.M204552200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M. (2010). Molecular approach to human leukemia: isolation and characterization of the first human retrovirus HTLV-1 and its impact on tumorigenesis in adult T-cell leukemia. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 86 117–130. 10.2183/pjab.86.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young M. R., Colburn N. H. (2006). Fra-1 a target for cancer prevention or intervention. Gene 379 1–11. 10.1016/j.gene.2006.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbini L. F., Wang Y., Cho J. Y., Libermann T. A. (2003). Constitutive activation of nuclear factor kappaB p50//p65 and Fra-1 and JunD is essential for deregulated interleukin 6 expression in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 63 2206–2215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T., Satou Y., Sugata K., Miyazato P., Green P. L., Imamura T., et al. (2011). HTLV-1 bZIP factor enhances TGF-beta signaling through p300 coactivator. Blood 118 1865–1876. 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]