Abstract

Objectives

The Stretching And strengthening for Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Hand (SARAH) randomised controlled trial evaluated the effectiveness of a hand exercise programme and demonstrated it was clinically effective and cost-effective at 12 months. The aim of this extended follow-up was to evaluate the effects of the SARAH programme beyond 12 months.

Methods

Using postal questionnaires, we collected the Michigan Hand Questionnaire hand function (primary outcome), activities of daily living and work subscales, pain troublesomeness, self-efficacy and health-related quality of life. All participants were asked how often they performed hand exercises for their rheumatoid arthritis. Mean difference in hand function scores were analysed by a linear model, adjusted for baseline score.

Results

Two-thirds (n=328/490, 67%) of the original cohort provided data for the extended follow-up. The mean follow-up time was 26 months (range 19–40 months).

There was no difference in change in hand function scores between the two groups at extended follow-up (mean difference (95% CI) 1.52 (−1.71 to 4.76)). However, exercise group participants were still significantly improved compared with baseline (p=0.0014) unlike the best practice usual care group (p=0.1122). Self-reported performance of hand exercises had reduced substantially.

Conclusions

Participants undertaking the SARAH exercise programme had improved hand function compared with baseline >2 years after randomisation. This was not the case for the control group. However, scores were no longer statistically different between the groups indicating the effect of the programme had diminished over time. This reduction in hand function compared with earlier follow-up points coincided with a reduction in self-reported performance of hand exercises. Further intervention to promote long-term adherence may be warranted.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN89936343; Results.

Keywords: Exercise, Adherance, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Hand therapy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

There was a lack of evidence regarding the long-term effectiveness of hand exercises for improving hand function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) beyond 12 months.

This paper reports on the extended follow-up (average follow-up of 26 months) of a trial evaluating the effectiveness of an individually tailored, progressive stretching and strengthening hand exercise programme for people with RA.

The benefits of the exercises evident at 12 months follow-up had reduced but not completely diminished, however, so had adherence with the exercise programme.

This study highlights the importance of supporting patients with RA to maintain regular exercise.

The extended follow-up was not planned at the start of the trial so the response rate is lower than that of the main trial.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common inflammatory polyarthritis.1 Hand dysfunction is common and to address this, exercises are recommended.2 3 Recommendations include exercises for enhancing flexibility, muscle strength and managing functional impairments.2 Limited evidence of the effectiveness of hand exercises for people with RA4–8 led to the commissioning of the Stretching and Strengthening for Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Hand (SARAH) trial (ISRCTN89936343).9 10 The SARAH trial demonstrated that an individually tailored, progressive stretching and strengthening hand exercise programme improved hand function and was cost effective compared with usual care over a 12-month period.11 12 However, there remained a lack of evidence regarding the long-term effect of hand exercises.

Adherence to any exercise programme is crucial.13 Support provided by health professionals enhances adherence with exercises but adherence is challenging when unsupervised.14 The SARAH exercise programme was prescribed by a physiotherapist or occupational therapist who provided a maximum of six supervisory sessions during a 3-month period. The median number of sessions actually attended by participants was 5 (IQR 5–6). During the sessions, exercises were tailored to ensure maximal effect, and adherence promoted using a well-recognised behavioural framework.15 It was intended that participants would carry out exercises daily at home during and beyond the supervised period.

The aim of the extended follow-up study was to estimate adherence to the intervention after the 3-month supervisory period, and the clinical effects of the SARAH exercise programme beyond 12 months.

Methods

Study design

A pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial carried out in 17 National Health Service (NHS) hospitals in the UK.11

Participants

Participants were adults (≥18 years) with RA affecting their hands, who were either not on a disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) regime or who had been on a stable DMARD regimen (including biologic agents) for 3 months or more. RA was defined using the American College of Rheumatology criteria.16 People who had upper limb surgery or fracture in the previous 6 months, were waiting for upper limb surgery or were pregnant were excluded.

Study procedures

Potential participants were approached during clinic visits or from clinic records (October 2009 to May 2011) and provided with a written invitation and information sheet. A researcher arranged an appointment to discuss the trial, check eligibility and if appropriate, complete baseline assessments and randomise participants. Follow-up data was collected 4 and 12 months after randomisation at face-to-face appointments. The extended follow-up (>12 months) was an addition to the original study protocol.9 Extended follow-up questionnaires were posted to all participants (unless they had withdrawn from the study or were deceased) between September 2012 and January 2013 so the time for extended follow-up varied between participants. Informed consent was provided by all participants. Participants who agreed to participate in the extended follow-up completed a response form indicating their consent and returned this with their questionnaire. Participants could request to complete the questionnaire over the phone. If participants did not respond to the extended follow-up invitation, one reminder letter was sent.

Interventions

The control intervention was best practice usual care consisting of joint protection education, advice on whole body mobility exercises and, if appropriate, functional splinting delivered over a maximum of three appointments. Participants in the intervention arm received best practice usual care and an individually tailored exercise programme, in which moderate-intensity to high-intensity strengthening and stretching exercises were prescribed. Therapists used supervisory sessions to provide advice, check tolerability, progress or regress exercises and promote adherence. Treatments are described in detail elsewhere.10

Data collection

Baseline measures

Measurements collected at baseline are described elsewhere.12 These included demographics, Michigan Hand Outcome Questionnaire (MHQ),17–19 pain troublesomeness,20 Arthritis Self-efficacy Scale,21 the EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire (EQ5D),22 the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12),23 impairment (grip strength, dexterity, hand and wrist range of motion and joint alignment), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C reactive protein (CRP), modified tender and swollen joint count of the hands and wrist24 and medication use.

Outcome measures

We reduced the number of outcomes included in the extended follow-up because of the postal mode of administration. Data collection was limited to self-reported measures and we were not able to include physical measures such as strength and dexterity that were measured at previous follow-up time points. To reduce participant burden, we did not use the whole MHQ and excluded lengthy health resource use questions. Outcome measures for the main trial are described in detail elsewhere.11

We collected the primary outcome (MHQ hand function subscale) for which scores ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better performance. Secondary outcomes were the activities of daily living (ADL) and work MHQ subscales, pain troublesomeness,20 participant-rated improvement, Arthritis Self-efficacy,21 the EuroQol EQ5D22 and the SF-12.23 To assess adherence with the exercise programme, all participants were asked to report how often they performed hand exercises for their RA.

Sample size estimates

The SARAH trial was sized to detect a small to moderate effect size of 0.3 in the primary outcome at 12 months. This was based on a previous smaller efficacy study of exercise that reported a standardised difference of 0.4 (8). We modified this effect downward (to 0.3) to account for the SARAH trial being a pragmatic multicentre trial and to reflect worthwhile effects found in other pragmatic studies of RA.25 To show this difference with 80% power at the 5% significance level, we required data on a total of 352 participants (using SAS procedure GLMPOWER) for analysis. Allowing for a 25% loss to follow-up, at least 469 participants were needed.

Randomisation

We used a central telephone randomisation service at the Warwick Clinical Trials Unit. Randomisation was stratified by centre, and used a variable block length. Allocation was computer generated and revealed once the participant was registered into the trial. It was not possible to blind participants and therapists delivering treatments to treatment allocation but follow-up data was collected by blinded research staff.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was intention to treat. Descriptive statistics were generated to compare people completing extended follow-up and those not, and the characteristics of randomised groups to identify any selection and retention biases. We only report earlier outcomes (baseline, 4 and 12 months) for those participants that took part in the extended follow-up. For all outcomes, we estimated within-group and between-group differences at each time point (as well as overall) using a linear model. Estimates of treatment effect were reported as the mean difference and 95% CI. All models were adjusted for baseline MHQ score and prerandomisation drug regime (biologic DMARDs, combination non-biologic DMARDs, single non-biologic DMARD and no DMARD). The inclusion of time-to-follow-up allowed adjustment for variable amounts of follow-up, and an estimation of the impact of duration of follow-up on the treatment effect. Multiple imputation estimates for MHQ overall hand function were also calculated for the extended follow-up time point and adjusted for hospital, age and sex. The multiple imputations took account of the MHQ hand function score for all time points and baseline data (age, CRP, ESR, SF-12 physical and mental summary scores, pain troublesomeness, confidence, impairment measurements and DMARD group).

Secondary outcome measures of change in pain, quality of life and self-efficacy were analysed in a similar manner. Patient-rated improvement was compared using the Wilcoxon test. Report of current exercise performance was categorised as at least three times per week, less than three times per week and no exercise and was analysed using Pearson's χ2.

Statistical analyses used SAS V.9.2 software (SAS Institute, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the sample

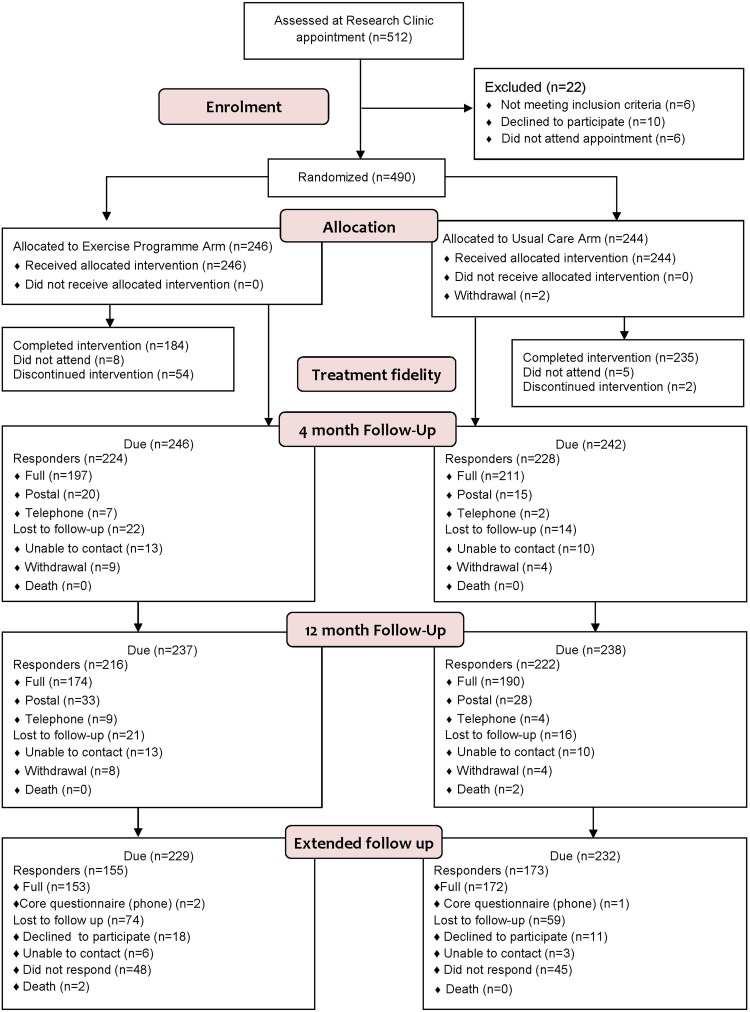

The baseline characteristics are given in table 1. Just over two-thirds of the original cohort (n=32 867 %) provided data (figure 1). On average, participants completed the extended follow-up 26 months after randomisation, with no difference between the groups (exercise: median time of 25.8 months (IQR 22.0–30.8); best practice usual care: median time of 26 months (IQR 22.2–29.9); p=0.6522). An analysis performed to see if the time of extended follow-up (which varied from 19–40 months after randomisation) was associated with outcome showed there was no significant time effect (p=0.1399).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants completing and not completing the extended follow-up by arm

| Characteristic by arm | Participants completing the extended follow-up | Participants not completing the extended follow-up | Participants completing the extended follow-up | Participants not completing the extended follow-up | Participants completing the extended follow-up | Participants not completing the extended follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study arm | Exercise programme |

Usual care |

Combined |

|||

| Age at randomisation, mean (SD) | 62.9 (11.0) | 58.6 (14.0) | 64.3 (10.8) | 61.5 (12.1) | 63.6 (10.9) | 59.8 (13.2) |

| Sex, F (%) | 77.4 | 74.7 | 74.0 | 81.2 | 75.6 | 77.5 |

| Ethnic origin, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 85 (93.4) | 153 (98.7) | 66 (95.7) | 169 (98.3) | 151 (93.4) | 322 (98.5) |

| Indian | 2 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) | – | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.3) | 3 (0.9) |

| Pakistani | – | – | 1 (1.5) | – | 1 (0.6) | – |

| Mixed | 2 (2.2) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.5) | – | 3 (1.9) | 1 (0.3) |

| Other | 2 (2.2) | – | 1 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.9) | 1 (0.3) |

| Disease duration (years), mean (SD) | 12.4 (10.8) | 14.4 (10.4) | 14.7 (12.5) | 12.4 (10.7) | 13.7 (11.8) | 13.5 (10.6) |

| Baseline ESR Median (IQR) | 13.0 (7.0, 26.0) | 21.0 (9.0,30.0) | 17.0 (9.0, 30.0) | 13.0 (8.0, 27.0) | 15.0 (8.0,28.0) | 18.5 (8.0, 28.5) |

| Baseline CRP Median (IQR) | 5.0 (3.0,11.0) | 6.5 (3.0,13.0) | 6.0, (3.0,13.0) | 6.0 (3.0, 11.0) | 5.0 (3.0, 12.0) | 6.0 (3.0, 12.0) |

| Medications, n (%) | ||||||

| Biologic DMARD | 30 (19.4) | 22 (24.2) | 35 (20.2) | 17 (24.6) | 65 (19.8) | 39 (24.4) |

| Combination non-biologic DMARD | 46 (29.7) | 26 (28.6) | 42 (24.3) | 11 (15.9) | 42 (26.8) | 37 (23.1) |

| Single non-biologic DMARD | 66 (42.6) | 37 (40.7) | 85 (49.1) | 33 (47.8) | 85 (46.0) | 70 (43.8) |

| Other medications | 13 (8.4) | 6 (6.6) | 11 (6.4) | 8 (11.6) | 11 (3.4) | 14 (8.8) |

| Baseline MHQ hand function, mean (SD) | 53.9 (15.1) | 48.9 (14.8) | 54.1 (15.6) | 47.0 (17.4) | 54.0 (15.4) | 48.1 (15.9) |

| Baseline SF-12 physical summary score, mean (SD) | 35.4 (9.7) | 31.1 (9.4) | 35.4 (9.7) | 32.1 (8.5) | 35.4 (9.7) | 31.5 (9.0) |

| Baseline SF-12 mental summary score, mean (SD) | 49.7 (10.5) | 45.5 (10.7) | 50.4 (10.4) | 45.1 (11.7) | 50.1 (10.4) | 45.3 (11.1) |

| Baseline EQ5D health state, mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.6 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.3) |

| Baseline pain troublesomeness score, mean (SD) | 43.1 (20.5 | 50.9 (24.2) | 46.0 (21.1) | 54.6 (21.6) | 44.6 (20.9) | 52.5 (23.1) |

| Baseline self-efficacy—confidence to manage their condition, mean (SD) | 69.5 (18.2) | 62.5 (23.0) | 71.3 (17.7) | 62.2 (21.0) | 70.5 (17.9) | 62.4 (22.1) |

| Participant reported frequency of hand exercises at 4 months, n (%) | ||||||

| At least 3 times a week | 107 (71.8) | 44 (67.7) | 80 (48.2) | 25 (45.5) | 187 (59.4) | 69 (57.5) |

| <3 times a week | 26 (17.5) | 11 (16.9) | 36 (21.7) | 5 (9.1) | 62 (19.7) | 16 (13.3) |

| No exercises | 16 (10.7) | 10 (15.4) | 50 (30.1) | 25 (45.5) | 66 (21.0) | 35 (29.2) |

| Participant-reported frequency of hand exercises at 12 months, n (%) | ||||||

| At least 3 times a week | 61 (40.4) | 18 (33.3) | 66 (39.1) | 18 (38.3) | 127 (39.7) | 36 (35.6) |

| <3 times a week | 53 (35.1) | 12 (22.2) | 35 (20.7) | 9 (19.1) | 88 (27.5) | 21 (20.8) |

| No exercises | 37 (24.5) | 24 (44.4) | 68 (40.2) | 20 (42.6) | 105 (32.8) | 44 (43.6) |

| Change in MHQ hand function baseline to 12 months, mean (SD) | 7.2 (13.6) | 9.8 (16.8) | 3.2 (16.0) | 4.8 (16.3) | 5.1 (15.0) | 7.5 (16.7) |

| Change in SF-12 physical summary score baseline to 12 months, mean (SD) | 0.8 (7.2) | 2.3 (6.3) | –0.1 (7.6) | 0.5 (6.7) | 0.3 (7.5) | 1.5 (6.5) |

| Change in SF-12 mental summary score baseline to 12 months, mean (SD) | 2.1 (9.9) | 2.4 (12.4) | 0.2 (9.5) | 1.1 (10.8) | 1.1 (9.7) | 1.8 (11.7) |

| Change in EQ5D health state baseline to 12 months, Mean (SD) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.3) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.3) |

CRP, C reactive protein; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; EQ5D, EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire, MHQ, Michigan Hand Outcome Questionnaire.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Flow diagram.

The two groups at extended follow-up were similar in age, gender, disease duration and baseline EQ-5D scores.

The characteristics of participants who did and did not respond to the extended follow-up are provided in table 1. The average age of responders was 63.6 years (SD 10.9) and 75.6% (248/328) were women, which was similar to the demographic of the entire sample at baseline. However, non-responders had worse hand function at baseline than responders (scores 48.1 and 54.0, respectively). The proportion of participants reporting that they were performing hand exercises for their RA at earlier follow-up points was higher among responders compared with non-responders (table 1) although the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.1323 and p=0.2598). Most notably, a greater proportion of non-responders in the exercise arm reported doing no exercise at 12 months compared with those who responded (44.4% vs 24.5%, respectively; p=0.0488).

Intervention adherence

Exercise programme participants reported substantially reducing their frequency of hand exercises over time with 71.4% reporting that they exercised three times per week at 4 months and only 31.4% at the extended follow-up (table 2). They had reported performing hand exercises for their RA more frequently than best practice usual care participants at the 4 and 12 months follow-up. At extended follow-up, there was no longer a clear difference between the two groups in their reports of hand exercises.

Table 2.

Participant-reported frequency of hand exercises for their RA (n (%)) for those that responded to the extended follow-up

| 4 months |

12 months |

Extended follow-up |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care | Exercise programme | Usual care | Exercise programme | Usual care | Exercise programme | |

| n=169 | n=152 | n=171 | n=155 | n=173 | n=155 | |

| Participant-reported frequency of hand exercises | ||||||

| At least three times a week | 80 (48.2) | 107 (71.8) | 66 (39.1) | 61 (40.4) | 60 (34.9) | 48 (31.4) |

| Less than three times a week | 36 (21.7) | 26 (17.5) | 35 (20.7) | 53 (35.1) | 38 (22.1) | 48 (31.4) |

| No exercises | 50 (30.1) | 16 (10.7) | 68 (40.2) | 39 (24.5) | 74 (43.0) | 57 (37.3) |

| Not answered | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| p trend (Wilcoxon) | <0.0001 | 0.0884 | 0.7715 | |||

RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

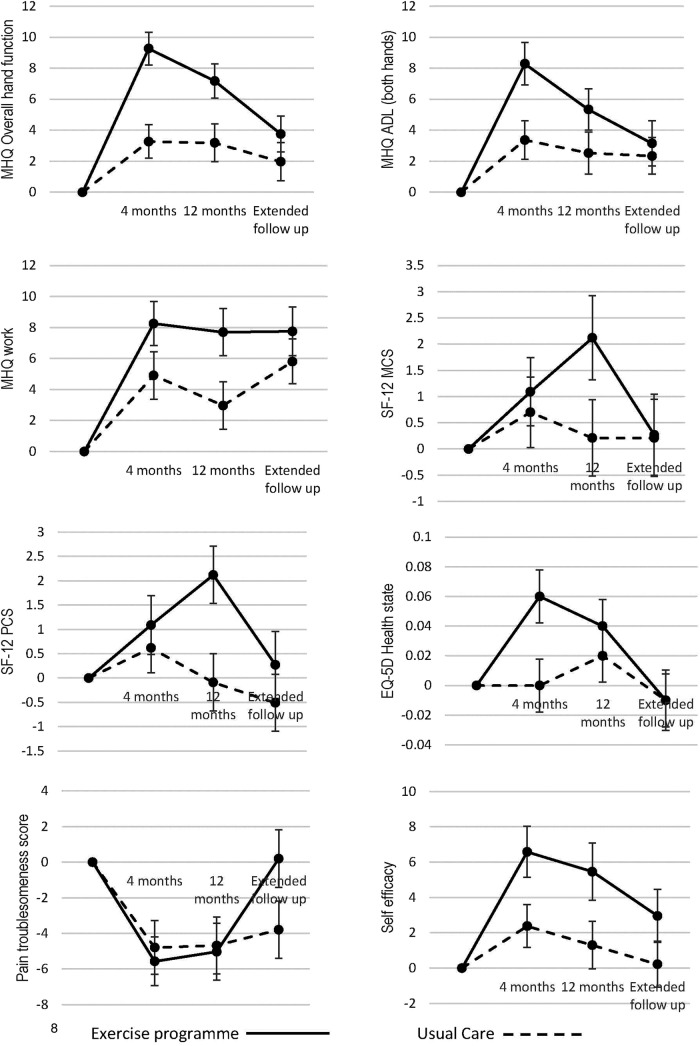

Primary outcome—hand function

Figure 2 and table 3 show the change in MHQ hand function subscale scores over time for those completing the extended follow-up. Best practice usual care resulted in small but statistically significant improvements in hand function at 4 and 12 months, in comparison with baseline values. However, the within-group difference between baseline and extended follow-up was not statistically significant (mean MHQ hand function subscale score at baseline =54.1 (SD=15.65); extended follow-up =56.1 (SD=18.85); p=0.1122).

Figure 2.

Mean change from baseline over time for the primary and secondary outcomes for those who responded to the extended follow-up. Error bars represent the SE. For the number of participants providing data for each outcome at each time point, please refer to table 3.

Table 3.

Estimates of effect in primary outcome and patient-reported secondary outcome measures for those who responded to the extended follow-up

| Mean change from baseline (95% CI) |

Mean treatment difference (95% CI) | p Value | Number of participants confirmed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care | Exercise programme | ||||

| MHQ overall hand function | |||||

| 4 months | 3.27 (1.15 to 5.39) | 9.27 (7.19 to 11.34) | 6.24 (3.56 to 8.92)*** | <0.0001 | 320 |

| 12 months | 3.19 (0.79 to 5.59) | 7.18 (5.02 to 9.33) | 3.91 (0.71 to 7.10)* | 0.0171 | 324 |

| Extended follow-up | 1.97 (−0.45 to 4.39) | 3.76 (1.50 to 6.02) | 1.52 (−1.71 to 4.76) | 0.3567 | 327 |

| MHQ ADL (both hands) | |||||

| 4 months | 3.37 (0.94 to 5.79) | 8.29 (5.61 to 10.96) | 5.07 (1.73 to 8.42)** | 0.0032 | 319 |

| 12 months | 2.53 (−0.12 to 5.18) | 5.34 (2.71 to 7.97) | 2.83 (−0.90 to 6.56) | 0.1375 | 323 |

| Extended follow-up | 2.34 (0.03 to 4.66) | 3.15 (0.30 to 6.01) | 0.72 (−2.88 to 4.32) | 0.6948 | 324 |

| MHQ work | |||||

| 4 months | 4.91 (1.91 to 7.91) | 8.26 (5.47 to 11.04) | 3.04 (−0.96 to 7.04) | 0.1370 | 316 |

| 12 months | 2.97 (−0.05 to 5.99) | 7.70 (4.73 to 10.68) | 4.44 (0.30 to 8.57)* | 0.0363 | 323 |

| Extended follow-up | 5.81 (2.97 to 8.65) | 7.76 (4.67 to 10.84) | 2.06 (−2.10 to 6.22) | 0.3318 | 315 |

| SF 12 Mental Component Score (MCS) | |||||

| 4 months | 0.70 (−0.62 to 2.02) | 1.09 (−0.18 to 2.37) | 0.51 (−1.16 to 2.18) | 0.5488 | 319 |

| 12 months | 0.21 (−1.21 to 1.64) | 2.12 (0.54 to 3.69) | 1.63 (−0.22 to 3.49) | 0.0857 | 322 |

| Extended follow-up | 0.21 (−1.23 to 1.66) | 0.27 (−1.25 to 1.78) | 0.22 (−1.71 to 2.15) | 0.8252 | 326 |

| SF 12 Physical Component Score (PCS) | |||||

| 4 months | 0.62 (−0.39 to 1.63) | 1.84 (0.65 to 3.02) | 1.37 (−0.12 to 2.86) | 0.0719 | 319 |

| 12 months | −0.09 (−1.24 to 1.06) | 0.76 (−0.39 to 1.92) | 0.72 (−0.79 to 2.23) | 0.3519 | 321 |

| Extended follow-up | −0.51 (−1.66 to 0.64) | 0.19 (−1.16 to 1.54) | 0.50 (−1.24 to 2.25) | 0.5720 | 326 |

| EQ-5D health state | |||||

| 4 months | 0.0 (−0.03 to 0.04) | 0.06 (0.02,0.09) | 0.03 (−0.01 to 0.07) | 0.1654 | 319 |

| 12 months | 0.02 (−0.02 to 0.05) | 0.04 (0.00 to 0.07) | 0.00 (−0.04 to 0.05) | 0.8239 | 0.322 |

| Extended follow-up | −0.01 (−0.05 to 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.05 to 0.03) | −0.01 (−0.06 to 0.04) | 0.6893 | 324 |

| Pain troublesomeness score† | |||||

| 4 months | −4.79 (−7.76 to −1.82) | −5.57 (−8.25 to −2.90) | −2.51 (−6.22 to 1.21) | 0.1872 | 315 |

| 12 months | −4.68 (−7.83 to −1.53) | −5.03 (−8.16 to −1.90) | −1.58 (−5.65 to 2.48) | 0.4454 | 322 |

| Extended follow-up | −3.79 (−6.93 to −0.64) | 0.20 (−2.98 to 3.38) | 3.23 (−0.83 to 7.28) | 0.1199 | 326 |

| Self-efficacy—confidence to manage their condition | |||||

| 4 months | 2.38 (−0.15 to 4.62) | 6.58 (3.74 to 9.42) | 3.41 (0.5 to 6.29)* | 0.0209 | 319 |

| 12 months | 1.30 (−1.32 to 3.92) | 5.46 (2.29 to 8.62) | 3.19 (0.71 to 6.98) | 0.1113 | 321 |

| Extended follow-up | 0.22 (−2.34 to 2.78) | 2.96 (0.03 to 5.90) | 2.30 (−1.20 to 5.79) | 0.1988 | 323 |

*p<0.05; ** p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

†Higher score, more pain.

ADL, activities of daily living; EQ-5D, EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire; MHQ, Michigan Hand Outcome Questionnaire.

Exercise resulted in substantial improvements from baseline, with the peak effect at 4 months. For 4 and 12 months, differences between the exercise and best practice usual care group were statistically and clinically significant. By the extended follow-up time point, the exercise intervention was still associated with a significant within-group improvement in hand function in comparison with baseline (mean MHQ hand function subscale score at baseline =53.9 (SD=15.1); extended follow-up=57.7 (SD=18.04); p=0.0014). However, the difference between exercise and best practice usual care interventions was no longer statistically significant (table 3).

Secondary outcomes

MHQ ADL and MHQ work subscales

Significant within-group differences were observed in both groups for the MHQ ADL and MHQ work subscales at the extended follow-up compared with baseline (p<0.05 and p<0.001 for best practice usual care and the exercise arms, respectively). Greater improvement from baseline was seen in the exercise arm (figure 2 and table 3).

There was a statistically significant between-group difference in the MHQ ADL subscale at 4 and 12 months and the MHQ work subscale at 12 months favouring the exercise arm but this difference was no longer significant at the extended follow-up.

Health-related quality of life (SF-12 and EQ-5D)

There were no observable within-group differences or between-group differences at any follow-up time point as measured by the SF-12 or the EQ-5D (figure 2 and table 3).

Pain troublesomeness

There were statistically significant within-group changes at the 4 and 12 months follow-up with both groups reporting less pain compared with baseline and this continued in the best practice usual care arm at extended follow-up (p=0.0196). However, the pain scores reported at extended follow-up in the exercise arm were similar to baseline scores (p=0.9039).

There was no statistically significant between-group difference in pain troublesomeness scores at any follow-up time point (figure 2 and table 3).

Self-efficacy

At extended follow-up, there was a significant within-group change in self-efficacy observed in the exercise arm but not the best practice usual care arm. Participants in the exercise group reported higher self-efficacy scores compared with their baseline scores (p=0.0496) but this was not the case for the best practice usual care (p=0.8675).

Respondents in the exercise arm reported higher self-efficacy scores at 4 months follow-up compared with the best practice usual care group but this difference was diminished at 12 months and extended follow-up so the between-group difference was no longer evident (figure 2 and table 3).

Participant-rated improvement

Participant-rated improvement in the exercise arm were significantly higher at 4 and 12 months follow-up than the best practice usual care group but there was no difference between the two groups at the extended follow-up (table 4).

Table 4.

Patient-reported secondary outcome measures (n (%)) for those that responded to the extended follow-up

| 4 months |

12 months |

Extended follow-up |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care | Exercise programme | Usual care | Exercise programme | Usual care | Exercise programme | |

| n=167 | n=149 | n=170 | n=151 | n=172 | n=153 | |

| Participant-rated improvement | ||||||

| Completely recovered | 1 (0.6) | – | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.6) | – |

| Much improved | 18 (10.8) | 34 (22.8) | 14 (8.2) | 31 (20.5) | 22 (12.8) | 25 (16.3) |

| Slightly improved | 34 (20.4) | 48 (32.2) | 23 (13.5) | 38 (25.2) | 17 (9.9) | 24 (15.7) |

| No change | 65 (38.9) | 45 (30.2) | 69 (40.6) | 47 (31.1) | 75 (43.6) | 58 (37.9) |

| Slightly worsened | 41 (24.6) | 17 (11.4) | 49 (28.8) | 22 (14.6) | 41 (23.8) | 35 (22.9) |

| Much worsened | 8 (4.8) | 5 (3.4) | 12 (7.1) | 9 (6.0) | 15 (8.7) | 7 (4.6) |

| Vastly worsened | – | – | 1 (0.6) | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.6) |

| p trend (Wilcoxon) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.2018 | |||

Multiple imputation

Multiple imputation was used to evaluate the impact of missing data and the estimate of treatment difference from baseline to extended follow-up was 1.75 (–1.20, 4.70), p=0.2433. This is similar to the non-imputed analysis suggesting that missing data was not a major influence on the study findings.

Discussion

We have evaluated the long-term outcomes of an individually tailored exercise programme compared with best practice usual care for adults with RA of the hand. Between-group differences had diminished over an average follow-up time of 26 months but generally functional scores favoured the exercise group. Both groups had improved hand function compared with baseline but this was only statistically significant in the exercise group. We interpret this to mean that although functional improvements due to the exercises had reduced, they had not diminished completely. Exercise arm participants completed treatment with their therapist ∼3 months after randomisation, so for some participants it had been 2 years since attending treatment. Therefore, it is very encouraging that some benefits still persisted. We aimed to estimate exercise adherence beyond the supervised period and the data shows that by the extended follow-up, many participants in the exercise arm were no longer exercising as intended. RA is a progressive disease, so regular exercise of sufficient intensity is needed to maintain muscle strength. It is likely that participants were no longer achieving a sufficient dose to maintain functional improvements.

Another study of upper limb exercises demonstrated a similar reduction of benefit over time where gains observed at 12 weeks were no longer evident at 26 weeks follow-up26 with an assumption it was due to reduced adherence but this data was not collected.

Another proposed mechanism by which the intervention improved function was by bolstering self-efficacy. This effect had also diminished which may be due to the fact it had been 2 years since attending treatment.

One outcome favoured the best practice usual care (pain troublesomeness scores). There were no between-group differences but the best practice usual care group had a small but statistically significant reduction in pain compared with baseline unlike the exercise group. However, the reduction in pain was small and we are confident the exercises did not increase pain while improving function. There was no difference in adverse events reported11 and we conclude that the exercise programme is safe.

Clinical implications and further research

The SARAH exercise programme is an effective adjunct to the medical management of RA for patients with hand problems, but the benefit from the exercise programme did reduce over time as participants reported doing less exercises. These findings raise important questions regarding how patients might be supported to exercise long term which is probably necessary to maintain functional gains.

Further research is needed to establish how ongoing support could be provided. Patients with RA are seen frequently in rheumatology outpatient clinics with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommending annual reviews for patients with RA.27 Staff could monitor patient's exercise participation during these appointments. However, there is uncertainty among health professionals about providing advice about exercise to patients with RA.28 29 Specialist rheumatology nurses play an important role in monitoring and supporting patients, yet, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for specialist rheumatology nurses do not mention exercise.30 There is a need to educate health professionals and patients about the importance of regular exercise. It is safe for patients with RA to exercise26 31 and health professionals need to be confident to advise on exercise regimes, referring to therapists when needed. Consideration should be given to how we can ensure all health professionals who see patients with RA can encourage adherence to exercise, for example, nurses or therapists working within primary care settings and not just specialist rheumatology clinics.

Patients with RA have to continually modify their treatment in response to changes in their condition. This also applies to exercise which presents another challenge. The SARAH programme is manualised, with clear instructions for progressing/regressing exercises allowing patients to modify exercises when needed. Participant feedback was that this was easy to follow12 so these types of resources could be made available to health professionals and patients to help patients to exercise regularly.

Methodological limitations

The response rate was lower than the main study. This was not unexpected as this follow-up was not planned at the outset of the study so participants were unaware they would receive the postal questionnaire. We only contacted participants by post so as not to place undue pressure on them to respond and only phoned those who requested to complete the questionnaire by phone. As a consequence, the analysis is underpowered to detect a difference in the primary and secondary outcomes. Loss to follow-up could introduce bias and there were some differences in responders and non-responders, but these were equal across treatment groups. Most notably, non-responders had poorer hand function at baseline and reported lower levels of exercise adherence at earlier follow-up especially in the exercise arm. It could be expected that responders would have better outcomes compared with non-responders resulting in an overestimate of the treatment effect. However, multiple imputation techniques estimated the effect of missing data and the results were largely similar indicating that missing data did not overly influence the findings. Overall, we are confident that the participants providing data were a good representation of the total cohort. The other factor that may have influenced findings was the disease status of participants. RA is a fluctuating condition, so disease status at the time of follow-up may have influenced outcomes but this information was not available.

In conclusion, a hand exercise programme is an effective adjunct to current drug management to improve hand function. Participants in the exercise group had improved hand function compared with baseline >2 years after randomisation. Hand function had reduced over time which coincided with a reduction in hand exercises highlighting the importance of promoting long-term exercise adherence among patients with RA.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow the Centre for Rehabilitation Research @RRIO_news

Collaborators: Collaborating NHS sites (names as of time of participation): Basingstoke and North Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (North Hampshire Hospital), Derby Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Royal Derby Hospital), Dorset Primary Care Trust (Victoria Hospital), George Eliot Hospital NHS Trust (George Eliot Hospital), Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust (Solihull Hospital), Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre NHS Trust (Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre), Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Poole General Hospital), Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust (Queen Alexandra Hospital), Royal Bournemouth NHS Foundation Trust (Christchurch Hospital), Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases NHS Foundation Trust (Bath Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases), South Warwickshire General Hospitals NHS Trust (Warwick Hospital and Stratford On Avon Hospital), Sussex Community NHS Trust (Bognor Regis War Memorial Hospital), Winchester and Eastleigh Healthcare Trust (Royal Hampshire County Hospital), Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust (Worcestershire Royal Hospital; Alexandra Hospital, Redditch; Kidderminster Hospital and Treatment Centre), Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh NHS Foundation Trust (Wrightington Hospital), University Hospitals Coventry & Warwickshire (University Hospital (Walsgrave site) and Rugby St Cross Hospital), University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust (Leicester Royal Infirmary and Leicester General Hospital). SARAH Trial team: Chief investigator: SEL. Coinvestigators: Dr J Adams, Prof MR Underwood, CMcC, Dr J Lord, Prof A Rahman. Trial lead: MW. Trial coordination/administration: SD, S Lowe, A Campbell, L Rattigan. Research fellows/associates: PH, EW, V Nichols. Trial statistician: CMcC. Health economists: Dr J Lord, C Crossan, Dr M Dritsaki, Dr M Glover. Research Clinicians (recruitment and data collection): Olivia Neely, Catherine Gibson, Karen Hotchkiss, Frances Chilton, Jessica Thrush, Catherine Minns-Lowe, Ann Birch, Linda Webber, Nicola Clague, Sue Kennedy, Kevin Spear, Sandi Derham, Dr Jenny Lewis, Sarah Bradley, Julie Cottrell, Paula White, Carole Frosdick, Jennifer Wilson, Nicola Bassett-Burr, Maggie Walsh. Intervention therapists (delivery of treatments): Lynda Myshrall, Jane Tooby, Cherry Steinberg, Mary Grant, Roslyn Handley, Fiona Jones, Clare Pheasant, Kate Hynes, Sue Kelly (UHCW NHS Trust); Joanne Newbold, Sally Thurgarland (George Eliot Hospital NHS Trust); Jane Dickenson, Lucy Mann (South Warwickshire Hospital NHS Trust); Alison Hinton, Rachel Chapman, Sunita Farmah, Collette James, Janice Wiltshire, Jane Simons (Worcester Acute Hospitals NHS Trust); Jane Martindale, Susan Hesketh, Alison Gerrard (Wrightington, Wigan & Leigh NHS Trust); Kirsty Bancroft, Corinna Cheng (Poole Hospital NHS Trust); Caroline Wood (Royal Bournemouth NHS Trust); Lisa Small, Karen Coales, Helen Ibbunson, Anne Bonsall (Bath Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases); Caroline Mountain, Jonathan Gibbons, Esther Mavurah, Hannah Susans (Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust); Nicola Spear, Becky Shaylor, Leon Ghulam (Basingstoke & North Hampshire Hospital NHS Trust); Sarah Wastell (Dorset NHS Trust); Christina MacLeod, Sapphire Patterson, Jane Vadher (Winchester & Eastleigh Healthcare NHS Trust); Karen Barker, Sue Gosling, Lizelle Sander-Danby, Jon Room, Aimee Fenn, Anne Richards, Pam Clarke, Gill Rowbotham, Nicky Nolan(Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre NHS Trust); Lorraine Kendall (Bognor Regis War Memorial Hospital); Claire Charnley (Solihull Hospital); Laura Richardson, Kate Wakefield (Leicester Royal Infirmary); Victoria Jansen, Liz Radbourne, Julie Tougher (Royal Derby Hospital).

Trial Steering Committee: Prof Alison Hammond (Chair), Dr Chris Deighton, Dr Chris McCarthy, SEL, MW, Mr John Wright (User representative). Data Monitoring Committee: Mr Ed Juszczak, Prof Paul Dieppe, Dr Helen Frost.

Contributors: EW contributed to designing the trial, data collection, interpretation of the data, drafting and revising of the paper and final approval of the version to be published. CMcC contributed to data analysis and interpretation, drafting and revising the paper and final approval of the version to be published. PH contributed to design of the trial, data collection, interpretation of the data, revision of the paper and final approval of the version to be published. SD participated in trial administration, data collection, revision of the paper and final approval of the version to be published. MW participated in designing the trial, data collection and interpretation of the data, revision of the paper and final approval of the version to be published. SEL participated in conceptualising and designing the trial, data analysis and interpretation, drafting and revising of the paper and the final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The SARAH trial was funded by the National Institute of Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme (NIHR HTA), project number 07/32/05. This project benefited from facilities funded through Birmingham Science City Translational Medicine Clinical Research and Infrastructure Trials Platform, with support from Advantage West Midlands (AWM). The preparation of this article was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Oxford at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Oxford C Multicenter Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 08/H0606/4).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data are available on request from the chief investigator (SEL).

Contributor Information

Collaborators: J Adams, MR Underwood, J Lord, A Rahman, S Lowe, A Campbell, L Rattigan, V Nichols, J Lord, C Crossan, M Dritsaki, M Glover, Olivia Neely, Catherine Gibson, Karen Hotchkiss, Frances Chilton, Jessica Thrush, Catherine Minns-Lowe, Ann Birch, Linda Webber, Nicola Clague, Sue Kennedy, Kevin Spear, Sandi Derham, Jenny Lewis, Sarah Bradley, Julie Cottrell, Paula White, Carole Frosdick, Jennifer Wilson, Nicola Bassett-Burr, Maggie Walsh, Lynda Myshrall, Jane Tooby, Cherry Steinberg, Mary Grant, Roslyn Handley, Fiona Jones, Clare Pheasant, Kate Hynes, Sue Kelly, Joanne Newbold, Sally Thurgarland, Jane Dickenson, Lucy Mann, Alison Hinton, Rachel Chapman, Sunita Farmah, Collette James, Janice Wiltshire, Jane Simons, Jane Martindale, Susan Hesketh, Alison Gerrard, Kirsty Bancroft, Corinna Cheng, Caroline Wood, Lisa Small, Karen Coales, Helen Ibbunson, Anne Bonsall, Caroline Mountain, Jonathan Gibbons, Esther Mavurah, Hannah Susans, Nicola Spear, Becky Shaylor, Leon Ghulam, Sarah Wastell, Christina MacLeod, Sapphire Patterson, Jane Vadher, Karen Barker, Sue Gosling, Lizelle Sander-Danby, Jon Room, Aimee Fenn, Anne Richards, Pam Clarke, Gill Rowbotham, Nicky Nolan, Lorraine Kendall, Claire Charnley, Laura Richardson, Kate Wakefield, Victoria Jansen, Liz Radbourne, and Julie Tougher

References

- 1.Symmons D, Turner G, Webb R, et al. . The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the United Kingdom: new estimates for a new century. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:793–800. 10.1093/rheumatology/41.7.793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deighton C, O'Mahony R, Tosh J, et al. . Management of rheumatoid arthritis: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2009;338:b702 10.1136/bmj.b702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luqmani R, Hennell S, Estrach C, et al. . British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology guideline for the management of rheumatoid arthritis (after the first 2 years). Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:436–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken450a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brighton SW, Lubbe JE, van der Merwe CA. The effect of a long-term exercise programme on the rheumatoid hand. Br J Rheumatol 1993;32:392–5. 10.1093/rheumatology/32.5.392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buljina AI, Taljanovic MS, Avdic DM, et al. . Physical and exercise therapy for treatment of the rheumatoid hand. Arthritis Rheum 2001;45:392–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dellhag B, Wollersjo I, Bjelle A. Effect of active hand exercise and wax bath treatment in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res 1992;5:87–92. 10.1002/art.1790050207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoenig H, Groff G, Pratt K, et al. . A randomized controlled trial of home exercise on the rheumatoid hand. J Rheumatol 1993;20:785–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Brien AV, Jones P, Mullis R, et al. . Conservative hand therapy treatments in rheumatoid arthritis--a randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:577–83. 10.1093/rheumatology/kei215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams J, Bridle C, Dosanjh S, et al. . Strengthening and stretching for rheumatoid arthritis of the hand (SARAH): design of a randomised controlled trial of a hand and upper limb exercise intervention--ISRCTN89936343. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:230 10.1186/1471-2474-13-230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heine PJ, Williams MA, Williamson E, et al. . Development and delivery of an exercise intervention for rheumatoid arthritis: strengthening and stretching for rheumatoid arthritis of the hand (SARAH) trial. Physiotherapy 2012;98:121–30. 10.1016/j.physio.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamb SE, Williamson EM, Heine PJ, et al. . Exercises to improve function of the rheumatoid hand (SARAH): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:421–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60998-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams MA, Williamson EM, Heine PJ, et al. . Strengthening And stretching for Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Hand (SARAH). A randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2015;19:1–222. 10.3310/hta19190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemmey AB, Marcora SM, Chester K, et al. . Effects of high-intensity resistance training in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1726–34. 10.1002/art.24891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swärdh E, Biguet G, Opava C. Views on exercise maintenance: variations among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Phys Ther 2008;88:1049–60. 10.2522/ptj.20070178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michie S, Rumsey N, Fussell A, et al Improving health: changing behaviour. NHS health trainer handbook. Manual. Department of Health Publications (Best Practice Guidance: Gateway Ref 9721). 2008. http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/12057/ (accessed 31 March 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of Rheumatology. Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002 update. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:328–46. 10.1002/art.10148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massy-Westropp N, Krishnan J, Ahern M. Comparing the AUSCAN Osteoarthritis Hand Index, Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire, and Sequential Occupational Dexterity Assessment for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2004;31:1996–2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Giesen FJ, Nelissen RG, Arendzen JH, et al. . Responsiveness of the Michigan Hand Outcomes Questionnaire--Dutch language version in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:1121–6. 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams J, Mullee M, Burridge J, et al. . Responsiveness of self-report and therapist-rated upper extremity structural impairment and functional outcome measures in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:274–8. 10.1002/acr.20078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parsons S, Carnes D, Pincus T, et al. . Measuring troublesomeness of chronic pain by location. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2006;7:34 10.1186/1471-2474-7-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorig K. Outcome measures for health education and other health care interventions. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996;37:53–72. 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenkinson C, Layte R. Development and testing of the UK SF-12 (short form health survey). J Health Serv Res Policy 1997; 2:14–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuchs HA, Brooks RH, Callahan LF, et al. . A simplified twenty-eight-joint quantitative articular index in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1989;32:531–7. 10.1002/anr.1780320504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lineker SC, Badley EM, Hawker G, et al. . Determining sensitivity to change in outcome measures used to evaluate hydrotherapy exercise programs for people with rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Care Res 2000;13:62–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manning VL, Hurley MV, Scott DL, et al. . Education, self-management, and upper extremity exercise training in people with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:217–27. 10.1002/acr.22102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. 2009 National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Rheumatoid arthritis in adults: management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg79. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iversen MD, Fossel AH, Ayers K, et al. . Predictors of exercise behavior in patients with rheumatoid arthritis 6 months following a visit with their rheumatologist. Phys Ther 2004;84:706–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurkmans EJ, de Gucht V, Maes S, et al. . Promoting physical activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: rheumatologists’ and health professionals’ practice and educational needs. Clin Rheumatol 2011;30:1603–9. 10.1007/s10067-011-1846-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Eijk-Hustings Y, van Tubergen A, Boström C, et al. . EULAR recommendations for the role of the nurse in the management of chronic inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:13–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooney JK, Law RJ, Matschke V, et al. . Benefits of exercise in rheumatoid arthritis. J Aging Res 2011;2011:681640 10.4061/2011/681640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.