Abstract

Background and objective

HSF1 is reported to be overexpressed in various solid tumors and play a pivotal role in cancer progression. A meta-analysis was conducted to assess the potential prognostic role of HSF1 in patients with solid tumors.

Methods

An extensive electronic search of three databases was performed for relevant articles. The pooled hazard ratios (HRs) or odds ratios with their corresponding 95% CI were calculated with a random-effects model. Heterogeneity and publication bias analyses were also conducted.

Results

A total of 3,159 patients from 10 eligible studies were included into the analysis. The results showed that positive HSF1 expression was significantly correlated with poor overall survival in all tumors (HR=2.09; 95% CI: 1.62–2.70; P<0.001). Subgroup analysis revealed that there was a significant association between HSF1 overexpression and poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) (HR=1.83; 95% CI: 1.21–2.77; P=0.004), breast cancer (BC) (HR=1.52; 95% CI: 1.24–2.86; P<0.001), hepatocellular carcinoma (HR=3.02; 95% CI: 1.77–5.18; P<0.001), non-small-cell lung cancer (HR=2.19; 95% CI: 1.20–3.99; P=0.01), and pancreatic cancer (HR=2.58; 95% CI: 1.11–6.03; P=0.03) but not in osteosarcoma (HR=1.58; 95% CI: 0.47–5.35; P=0.46). In addition, HSF1 overexpression was significantly associated with some phenotypes of tumor aggressiveness including TNM stage, histological grade, lymph node metastasis, and vascular invasion.

Conclusion

HSF1 overexpression may prove to be an unfavorable prognostic biomarker for solid tumor patients.

Keywords: HSF1, solid tumors, prognosis, overall survival, meta-analysis

Introduction

Cancer remains a growing public health problem worldwide due to the increasing tendency of overall morbidity over the past decades. Despite the improvements in diagnostic methods and treatment techniques, the 5-year survival rate for all tumors is not optimistic, especially in developing countries.1,2 Therefore, there is an urgent need to seek reliable and feasible tumor biomarkers to assist in obtaining additional prognostic information.

HSF1 is the master regulator of proteotoxic stress response that protects cells against heat, inflammation, ischemia, and other noxious conditions. HSF1 exists primarily as an inactive monomer located in the cytoplasm and is dispensable for cellular viability under normal proteome homeostasis conditions.3 However, in the event of proteotoxic stress, this inactive monomeric HSF1 forms a phosphorylated trimer and then triggers the transcription of heat shock proteins (HSPs) by binding to consensus heat shock elements (HSE).4,5 HSPs such as HSP27, HSP70, and HSP90 are important molecular chaperones that promote proper folding, transportation, and degradation of proteins within cells. Simultaneously, HSF1 activation is repressed by interaction with HSP overexpression in nontumor cells. In tumor cells, however, this feedback inhibition may be ineffective.6,7

Identification of many prognostic factors in recent years has helped more accurate prognostic prediction of tumor patients. Growing studies have demonstrated that HSF1 is overexpressed in a series of solid tumors such as esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC),8,9 breast cancer (BC),10,11 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC),12–14 osteosarcoma,15 non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC),16 and pancreatic cancer.17 Furthermore, evidence implies that the elevation of HSF1 expression is correlated with poor survival of tumor patients.18,19 Nevertheless, the results of these individual studies are not consistent and conclusive because of the small sample size. The aim of the present meta-analysis is to make a comprehensive analysis on potential prognostic and clinicopathological roles of HSF1 in solid tumors.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

This meta-analysis was performed by following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) criteria.20 A systematic literature search in the PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science was performed by two investigators independently (updated on June 15, 2017) by retrieving articles published in English only and using the following search terms: (“heat shock factor 1” or “HSF1”) and (“tumor” or “neoplasm” or “cancer” or “carcinoma”) and (“prognosis” or “prognostic”). We also manually cross-searched the citation lists of relevant studies to identify additional eligible articles. In case of overlapping cohorts, only the most recent article was considered for inclusion.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) studies that evaluated the prognostic value of HSF1 in patients with solid tumors; 2) studies in which HSF1 expression was detected in tumor tissues; 3) studies that reported hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CI for overall survival (OS) or provided sufficient data for calculated HR and 95% CI; 4) studies that divided patients into HSF1 high expression and HSF1 low/negative (neg) expression groups, regardless of the cutoff value; and 5) studies published in English. Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) reviews, case reports, conference abstracts, letters to the editor, and laboratory studies; 2) over-lapping or repeat analyses; and 3) insufficient data for further analysis.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two investigators independently reviewed all eligible studies, and any disagreement between the investigators was resolved by consensus. Data extracted from the articles included the following items: first author, year of publication, study region, tumor type, cases, TNM staging (according to the 2009 International Union Against Cancer Tumour Node Metastasis Classification System, 7th edition), detection method, cutoff value, survival outcomes, and median follow-up months. If studies did not directly provide HR for OS, the Engauge Digitizer V4.1 combined Tierney’s method was utilized to estimate HR and 95% CIs from Kaplan–Meier curves.21 The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was applied to assess the quality of all included studies, and studies with an NOS score of ≥7 were considered high quality.

Statistical analysis

Stata 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and RevMan software 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) were used to conduct all the statistical analyses. The combined HR and 95% CI were calculated to assess the association between HSF1 expression and OS of solid tumor patients. The overall HR >1 that failed to overlap its 95% CI indicated a poor prognosis in patients with HSF1 overexpression. In addition, the pooled odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI were used to evaluate the correlation between HSF1 expression and the clinicopathological parameters of solid tumors. Heterogeneity was measured using the Higgins I2 test. Significant heterogeneity among studies was defined as I2>50%.22 Taking into account the relatively small meta-analysis, the random-effects model was always applied to provide better estimates with wider CIs.23 Publication bias was statistically assessed via the Egger’s test and visually evaluated by funnel plots.24 We also performed the sensitivity analysis by sequentially omitting each individual study to validate the stability of the synthetic results. Two-tailed P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study selection and demographic characteristics

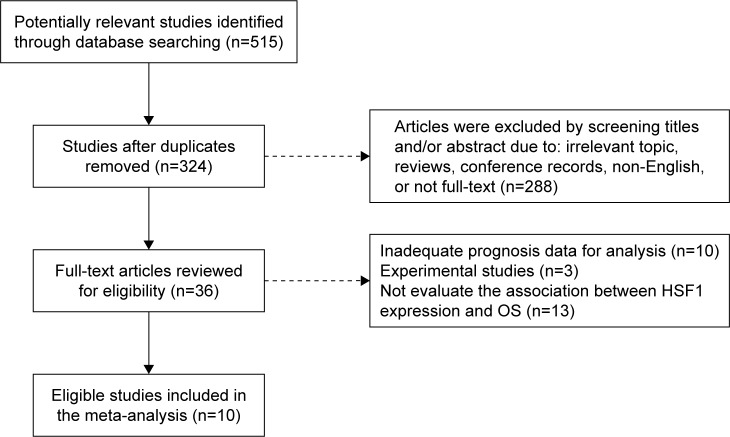

The initial search strategy identified 515 potentially relevant articles. After further screening, a total of 10 studies involving 3,159 patients were finally included in this meta-analysis.8–17 The details of the study selection process are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A flow diagram of the study selection process.

Abbreviations: HSF1, heat shock factor 1; IHC, immunohistochemistry; OS, overall survival.

As for the tumor type involving ESCC, BC, HCC, osteosarcoma, NSCLC, and pancreatic cancer, HSF1 expression was detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC). All the 10 studies investigated the prognostic role of HSF1 in OS, and only three studies focused on disease-free survival (DFS).9,15,16 HR with the corresponding 95% CI was directly extracted through multivariate analyses in seven studies,8–14 and HR in the remaining three studies15–17 was calculated from Kaplan–Meier survival curves by the Tierney’s methods. The quality of all the 10 studies was assessed by NOS, and the scores ranged from 5 to 8 (median 6.7), suggesting that the methodological quality was relatively high (Table S1). The main characteristics of the 10 eligible studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Year | Country | Cancer type | Case | HSF1 positive (%) | TNM stage | Detection method | Cutoff value (positive) | Outcome | MFu time (months) | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsukao et al8 | 2017 | Japan | ESCC | 212 | 109 (51.4) | I–IV | IHC | Score ≥2 (range 0–3)a | OS | 60 | 8 |

| Liao et al9 | 2015 | China | ESCC | 134 | 76 (56.7) | I–IV | IHC | Score ≥7 (range 0–12)b | OS/DFS | 25 | 6 |

| Gokmen-Polar and Badve10 | 2016 | USA | BC | 210 | 161 (76.7) | NR | IHC | NR | OS | NR | 6 |

| Santagata et al11 | 2011 | USA | BC | 1,841 | 1,437 (78.1) | I–III | IHC | Score ≥1 (range 0–2)a | OS | 179 | 8 |

| Chuma et al12 | 2014 | Japan | HCC | 226 | 115 (50.9) | I–IV | IHC | Positively stained cells >30% | OS | 60 | 8 |

| Zhang et al13 | 2013 | China | HCC | 103 | 48 (46.6) | I–III | IHC | Score ≥8 (range 0–15)b | OS | 38 | 7 |

| Fang et al14 | 2012 | China | HCC | 213 | 105 (49.3) | NR | IHC | Score ≥2 (range 0–3)a | OS | 25 | 6 |

| Zhou et al15 | 2017 | China | Osteosarcoma | 65 | 37 (56.9) | NR | IHC | Score ≥2 (rang of 0–3)a | OS/DFS | NR | 5 |

| Cui et al16 | 2015 | China | NSCLC | 105 | 45 (42.9) | I–III | IHC | Score ≥4 (range 0–7)b | OS/DFS | 60 | 7 |

| Liang et al17 | 2017 | China | Pancreatic cancer | 50 | 37 (74.0) | I–IV | IHC | Positively stained cells >25% | OS | NR | 6 |

Notes:

The immunohistochemical scoring system was based on the staining intensity.

The immunohistochemical scoring system was based on the proportion of positively stained cells combined with the staining intensity.

Abbreviations: BC, breast cancer; DFS, disease-free survival; ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HSF1, heat shock factor 1; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa Scale; NR, not reported; MFu, median Follow-up; OS, overall survival.

Evidence synthesis

Overall survival

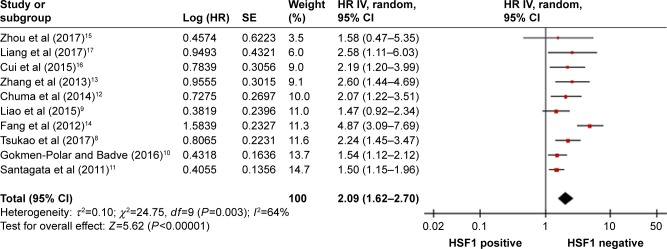

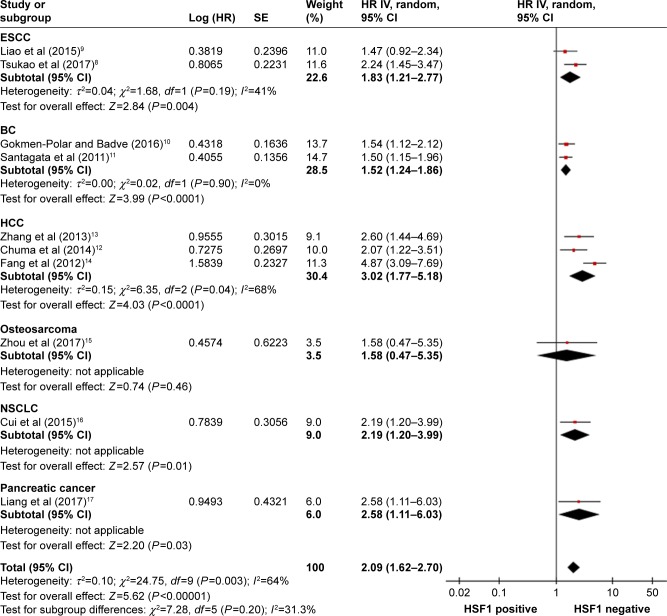

The pooled results showed that tumor patients with positive (pos) HSF1 expression had a significantly poor OS (HR=2.09; 95% CI: 1.62–2.70; P<0.001). Owing to the obvious heterogeneity in the synthesis analysis (I2=64%; 95% CI: 28%–82%), a random-effects model was applied (Figure 2). In addition, when the subgroup analysis was completed according to tumor type (Figure 3), the pooled HR revealed an association between HSF1 overexpression and unfavorable prognosis in patients with ESCC (HR=1.83; 95% CI: 1.21–2.77; P=0.004), BC (HR=1.52; 95% CI: 1.24–2.86; P<0.001), HCC (HR=3.02; 95% CI: 1.77–5.18; P<0.001), NSCLC (HR=2.19; 95% CI: 1.20–3.99; P=0.01), and pancreatic cancer (HR=2.58; 95% CI: 1.11–6.03; P=0.03) but not in osteosarcoma (HR=1.58; 95% CI: 0.47–5.35; P=0.46).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of studies evaluating the association between HSF1 expression level and OS in patients with solid tumors.

Abbreviations: HSF1, heat shock factor 1; IHC, immunohistochemistry; OS, overall survival; SE, standard error; IV, inverse variance; M–H, Mantel–Haenszel.

Figure 3.

Forest plot describing the HRs and their corresponding CIs by tumor type subgroups.

Abbreviations: HRs, hazard ratios; IV, inverse variance.

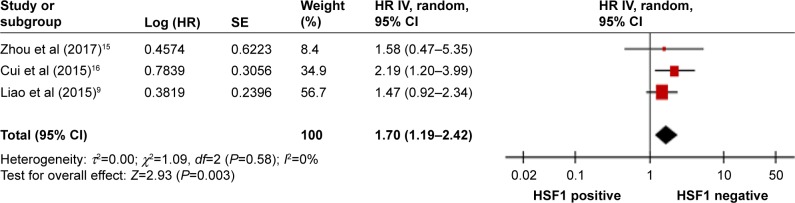

Disease-free survival

Only three studies comprising 304 patients evaluated the association between HSF1 and DFS, and the HR for DFS showed that HSF1 overexpression was significantly correlated with worse DFS (HR=1.70; 95% CI=1.19–2.42; P=0.003; Figure 4). A random-effects model was used because of the small meta-analysis.

Figure 4.

Forest plot showing the correlation between HSF1 overexpression and disease-free survival in patients with solid tumors.

Abbreviations: HSF1, heat shock factor 1; HRs, hazard ratios; IV, inverse variance.

Clinicopathological parameters

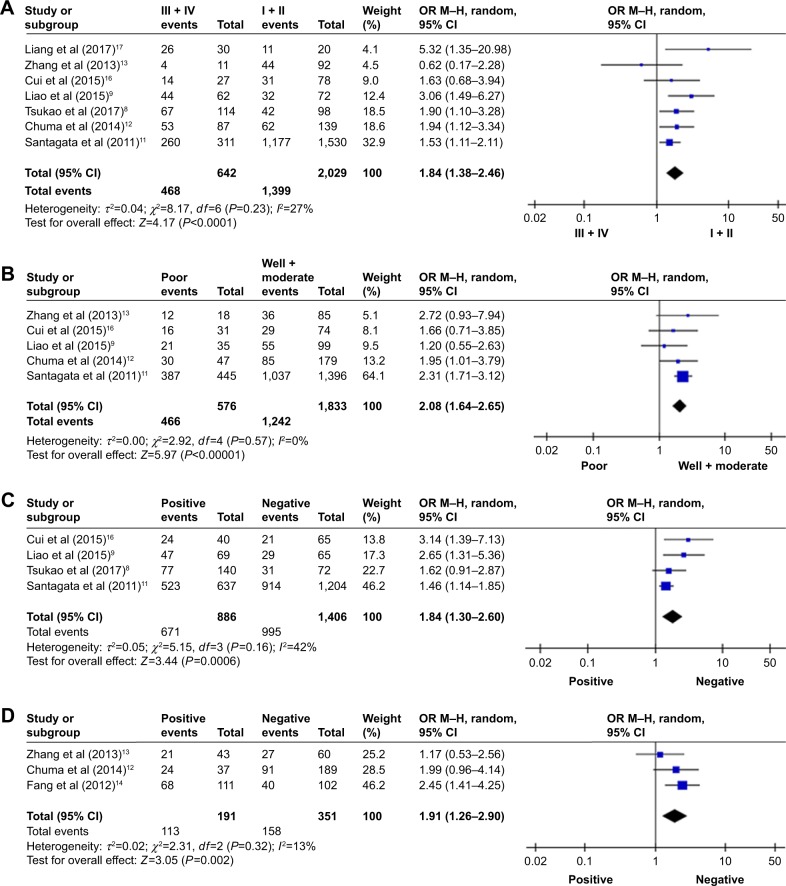

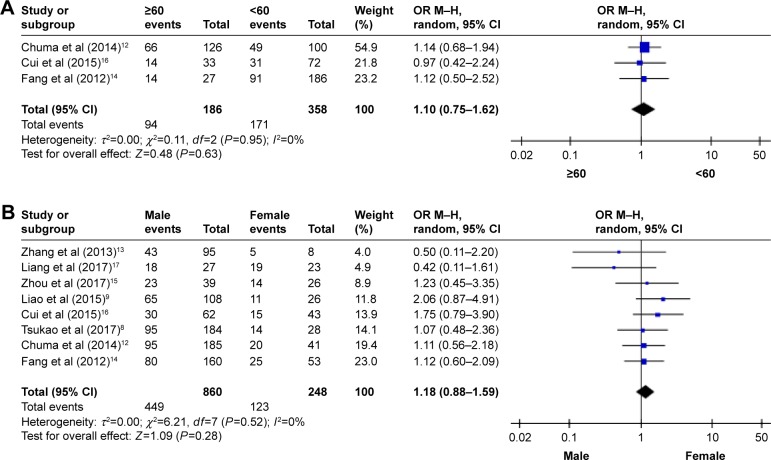

To comprehensively explore the role of HSF1 expression as a biomarker in solid tumors, we also investigated the association between HSF1 overexpression and clinicopathological parameters of the patients. As illustrated in Figures 5 and 6, the combined data suggested that HSF1 overexpression was significantly associated with some phenotypes of tumor aggressiveness including TNM stage (III + IV vs I + II; OR=1.84; 95% CI: 1.38–2.46; P<0.001), histological grade (poor vs well + moderate; OR=2.08; 95% CI: 1.64–2.65; P<0.001), lymph node metastasis (pos vs neg; OR=1.84; 95% CI: 1.30–2.60; P<0.001), and vascular invasion (pos vs neg; OR=1.91; 95% CI: 1.26–2.90; P=0.002). However, HSF1 expression had no obvious association with the following parameters: age (≥60 vs <60 years; OR=1.10; 95% CI: 0.75–1.62; P=0.63) and gender (male vs female; OR=1.18; 95% CI: 0.88–1.59; P=0.28). In view of the fact that the above subgroup analyses were relatively small meta-analyses and then the random-effects model was utilized. The details of the meta-analysis results are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Forest plots of ORs for the associations between HSF1 overexpression and clinicopathological features in solid tumors. Note: (A) TNM stage, (B) histological grade, (C) lymph node metastasis, and (D) vascular invasion.

Abbreviations: HSF1, heat shock factor 1; ORs, odds ratios.

Figure 6.

Forest plots of ORs for the associations between HSF1 overexpression and clinicopathological features in solid tumors. Note: (A) Age and (B) gender.

Abbreviations: HSF1, heat shock factor 1; ORs, odds ratios.

Table 2.

Main meta-analysis results of HSF1 overexpression in patients with solid tumors

| Analysis | Number of studies | Number of patients | HR (95% CI) | P-value | Heterogeneity

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (%) | Ph | |||||

| Overall survival | 10 | 3,159 | 2.09 (1.62–2.70) | <0.001 | 64 | 0.003 |

| Disease-free survival | 3 | 304 | 1.70 (1.19–2.42) | 0.003 | 0 | 0.58 |

| Clinicopathological parameters | OR (95% CI) | |||||

| TNM stage (III + IV vs I + II) | 6 | 2,621 | 1.71 (1.37–2.14) | <0.001 | 12 | 0.34 |

| Histological grade (poor vs well + moderate) | 5 | 2,409 | 2.10 (1.66–2.67) | <0.001 | 0 | 0.57 |

| Lymph node metastasis (pos vs neg) | 4 | 2,292 | 1.63 (1.32–2.00) | <0.001 | 42 | 0.16 |

| Vascular invasion (pos vs neg) | 3 | 542 | 1.94 (1.32–2.84) | <0.001 | 13 | 0.32 |

| Age (≥60 vs <60) (years) | 3 | 544 | 1.10 (0.75–1.62) | 0.63 | 0 | 0.95 |

| Gender (male vs female) | 7 | 1,058 | 1.24 (0.92–1.69) | 0.16 | 0 | 0.70 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; neg, negative; OR, odds ratio; pos, positive.

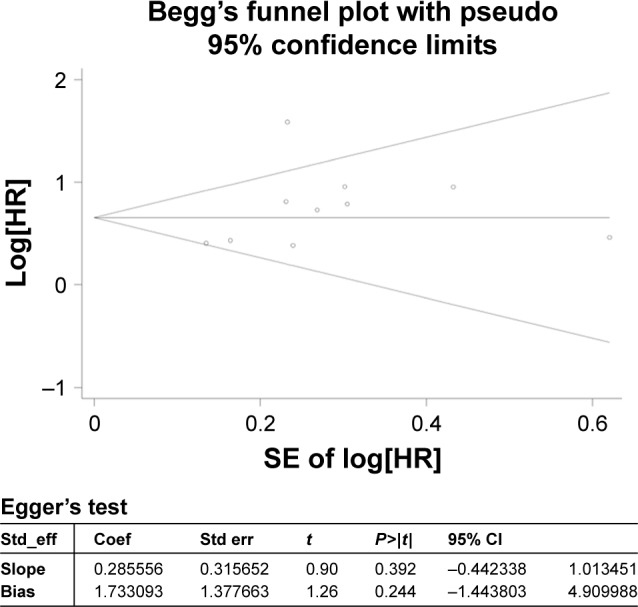

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

We sequentially removed each single study to determine whether any individual study could affect the pooled HR for OS, and the result of random-effects sensitivity analysis was neg (Figure S1). Furthermore, we performed Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test to evaluate the potential publication bias for all articles in the current meta-analysis. As shown in Figure 7, the shape of the funnel plot was relatively symmetrical and the P-value of Egger’s test was 0.244, both of which indicate that there was no obvious risk of publication bias. Thus, these test results verified that the synthetic evidence was robust and reliable.

Figure 7.

Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test evaluating the publication bias of the included studies.

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

Biological organisms from bacteria to animals can respond to a wide variety of environmental stressors. When these noxious factors disrupt the state of protein homeostasis and elicit proteotoxic stress in cells, cytoprotective molecular chaperones known as HSPs are induced to counteract such stresses. It is generally accepted that the heat-shock response in eukaryotes is mediated via the regulatory effect of HSF1 on the expression of HSPs.25–27 Accordingly, HSF1 function is not only critical to overcome the proteotoxic stress but also necessary for OS of cells and the proper development of the organisms.

Recently, a number of clinical studies have revealed that HSF1 is overexpressed in patients with various solid tumors28,29 and the elevated expression of HSF1 expression is closely associated with some phenotypes of tumor aggressiveness.30 These findings urge researchers to postulate whether HSF1 expression could serve as a valuable prognostic factor for better clinical decision making in tumor patients. However, no meta-analysis has been conducted to assess the prognostic and clinicopathological values of HSF1 overexpression so far.

In the present meta-analysis, we systematically evaluated the survival data from 10 independent studies involving 3,159 patients with solid tumors. The similarity in these included studies was to explore the potential prognostic role of HSF1 in solid tumor patients based on the survival analysis, and the difference between them was mainly determined by the different subjects and the methods of research, including cancer types, population distribution, sample size, cutoff value, and follow-up time. The subsequent combined results suggested that HSF1 expression was an independent unfavorable predictor for solid tumors, which was significantly negatively correlated with OS and DFS of tumor patients. Our further subgroup analysis also supports that HSF1 overexpression was significantly correlated with advanced tumor stage, poor histological grade, pos lymph node metastasis, and vascular invasion, indicating that HSF1 plays many important roles in tumor progression via regulating invasion and metastasis of malignant cells and finally affects tumor prognosis.

Furthermore, liquid biopsies (LBs) have been rapidly developed in the domain of oncology and the clinical applications will gradually expand in the near future. If HSF1 expression level can be measured in LB samples, it may exceptionally yield useful information for early diagnosis of tumors and indicate appropriate treatment strategy for individual patients based on the molecular analysis.

The results of evidence synthesis combined with published studies have demonstrated that HSF1 functions as a powerful multifaceted regulator in tumorigenesis and tumor development. In fact, the molecular mechanisms of HSF1 promoted the malignant phenotypic tendency of cancer were inconsistent in each study and the main molecular mechanisms are as follows. First, HSF1 activation promotes the expression of HSPs including HSP27, HSP70, and HSP90, thus facilitating transition of cells from normal to malignant phenotypes.31–33 Second, there is already evidence that a variety of signaling pathways are triggered by HSF1 in solid tumors.12,30,33–36 These signaling pathways are coordinated with each other to drive tumorigenesis, tumor development, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), proliferation, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, and antiapoptosis of tumor cells. In addition, studies have indicated that HSF1 regulates intracellular metabolism reprogramming, especially glycolysis and lipid metabolism.37,38 The reprogramming of metabolism patterns allows tumor cells to meet the massive energy demands and the biosynthetic needs of malignant growth. Finally, HSF1 also possesses the ability to upregulate or downregulate the expression of microRNAs and long noncoding RNAs, both of which play critical roles in tumor progression.39,40

Nevertheless, this meta-analysis has some limitations. First, given the limited number of included studies for a comprehensive analysis, the pooled conclusions may be less powerful and should be interpreted with caution, especially in osteosarcoma. Second, all the 10 eligible studies were of retrospective nature. In addition, three studies did not directly provide HR and 95% CI; rather they extracted the data from survival curves, which may introduce bias. Third, there existed a high level of undetected heterogeneity among subgroup analyses, which we suppose may be attributed to the smaller numbers of studies, different tumor types, or pos cutoff values. However, we could not completely eliminate the heterogeneity because only summarized data could be used. Larger multicenter prospective studies are required to further verify the prognostic and clinicopathological significances of HSF1 expression in solid tumors.

Conclusion

The findings of our meta-analysis provide preliminary evidence that HSF1overexpression is associated with unfavorable prognosis in various solid tumors. HSF1 may prove to be a promising prognostic biomarker and a potential specific therapeutic target for solid tumors. Of course, more investigations on molecular mechanisms underlying the regulatory effect of HSF1 are required to verify our postulation.

Supplementary materials

The random-effects sensitivity analysis of the OS.

Abbreviation: OS, overall survival.

Table S1.

Evaluations of the qualities of the included studies based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

| Author | Selection

|

Comparability

|

Outcome

|

Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Representativeness of the exposed cohort | 2) Selection of the nonexposed cohort | 3) Ascertainment of exposure | 4) Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study | 1) Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | 1) Assessment of outcome | 2) Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur | 3) Adequacy of follow up of cohorts | ||

| Tsukao et al1 | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 8 | |

| Liao et al2 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | ||

| Gokmen-Polar and Badve3 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | ||

| Santagata et al4 | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 8 | |

| Chuma et al5 | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 8 | |

| Zhang et al6 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7 | |

| Fang et al7 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | ||

| Zhou et al8 | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | |||

| Cui et al9 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7 | |

| Liang et al10 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | ||

Note: The “*” denotes 1 point and “**” denotes 2 points.

References

- 1.Tsukao Y, Yamasaki M, Miyazaki Y, et al. Overexpression of heat-shock factor 1 is associated with a poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2017;13(3):1819–1825. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liao Y, Xue Y, Zhang L, Feng X, Liu W, Zhang G. Higher heat shock factor 1 expression in tumor stroma predicts poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients. J Transl Med. 2015;13:338. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0703-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gokmen-Polar Y, Badve S. Upregulation of HSF1 in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(51):84239–84245. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santagata S, Hu R, Lin NU, et al. High levels of nuclear heat-shock factor 1 (HSF1) are associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(45):18378–18383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115031108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chuma M, Sakamoto N, Nakai A, et al. Heat shock factor 1 accelerates hepatocellular carcinoma development by activating nuclear factor-kappaB/mitogen-activated protein kinase. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(2):272–281. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang JB, Guo K, Sun HC, et al. Prognostic value of peritumoral heat-shock factor-1 in patients receiving resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(6):1648–1656. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang F, Chang R, Yang L. Heat shock factor 1 promotes invasion and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Cancer. 2012;118(7):1782–1794. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Z, Li Y, Jia Q, et al. Heat shock transcription factor 1 promotes the proliferation, migration and invasion of osteosarcoma cells. Cell Prolif. Epub. 2017 Apr 1;50(4) doi: 10.1111/cpr.12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui J, Tian H, Chen G. Upregulation of nuclear heat shock factor 1 contributes to tumor angiogenesis and poor survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(2):465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang W, Liao Y, Zhang J, et al. Heat shock factor 1 inhibits the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway by regulating second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase to promote pancreatic tumorigenesis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0537-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Acknowledgments

We thank Doctor Yanfang Zhao (Department of Health Statistics, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, China) for her critical revision of the meta-analysis section. The project was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2015J01561).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorger PK. Heat shock factor and the heat shock response. Cell. 1991;65(3):363–366. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90452-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anckar J, Sistonen L. Regulation of HSF1 function in the heat stress response: implications in aging and disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:1089–1115. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060809-095203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai C, Sampson SB. HSF1: guardian of proteostasis in cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(1):17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Thonel A, Le Mouel A, Mezger V. Transcriptional regulation of small HSP-HSF1 and beyond. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44(10):1593–1612. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rappa F, Farina F, Zummo G, et al. HSP-molecular chaperones in cancer biogenesis and tumor therapy: an overview. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(12):5139–5150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsukao Y, Yamasaki M, Miyazaki Y, et al. Overexpression of heat-shock factor 1 is associated with a poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2017;13(3):1819–1825. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liao Y, Xue Y, Zhang L, Feng X, Liu W, Zhang G. Higher heat shock factor 1 expression in tumor stroma predicts poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients. J Transl Med. 2015;13:338. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0703-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gokmen-Polar Y, Badve S. Upregulation of HSF1 in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(51):84239–84245. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santagata S, Hu R, Lin NU, et al. High levels of nuclear heat-shock factor 1 (HSF1) are associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(45):18378–18383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115031108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chuma M, Sakamoto N, Nakai A, et al. Heat shock factor 1 accelerates hepatocellular carcinoma development by activating nuclear factor-kappaB/mitogen-activated protein kinase. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(2):272–281. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang JB, Guo K, Sun HC, et al. Prognostic value of peritumoral heat-shock factor-1 in patients receiving resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(6):1648–1656. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang F, Chang R, Yang L. Heat shock factor 1 promotes invasion and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Cancer. 2012;118(7):1782–1794. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Z, Li Y, Jia Q, et al. Heat shock transcription factor 1 promotes the proliferation, migration and invasion of osteosarcoma cells. Cell Prolif. 2017 Apr 1; doi: 10.1111/cpr.12346. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui J, Tian H, Chen G. Upregulation of nuclear heat shock factor 1 contributes to tumor angiogenesis and poor survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(2):465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang W, Liao Y, Zhang J, et al. Heat shock factor 1 inhibits the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway by regulating second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase to promote pancreatic tumorigenesis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0537-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendillo ML, Santagata S, Koeva M, et al. HSF1 drives a transcriptional program distinct from heat shock to support highly malignant human cancers. Cell. 2012;150(3):549–562. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciocca DR, Arrigo AP, Calderwood SK. Heat shock proteins and heat shock factor 1 in carcinogenesis and tumor development: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2013;87(1):19–48. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0918-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Grp P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(pt A):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br Med J. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shamovsky I, Nudler E. New insights into the mechanism of heat shock response activation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(6):855–861. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7458-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doyle SM, Genest O, Wickner S. Protein rescue from aggregates by powerful molecular chaperone machines. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14(10):617–629. doi: 10.1038/nrm3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujimoto M, Nakai A. The heat shock factor family and adaptation to proteotoxic stress. FEBS J. 2010;277(20):4112–4125. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engerud H, Tangen IL, Berg A, et al. High level of HSF1 associates with aggressive endometrial carcinoma and suggests potential for HSP90 inhibitors. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(1):78–84. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cen H, Zheng S, Fang YM, Tang XP, Dong Q. Induction of HSF1 expression is associated with sporadic colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(21):3122–3126. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i21.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabai VL, Meng L, Kim G, Mills TA, Benjamin IJ, Sherman MY. Heat shock transcription factor Hsf1 is involved in tumor progression via regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and RNA-binding protein HuR. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(5):929–940. doi: 10.1128/MCB.05921-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng L, Gabai VL, Sherman MY. Heat-shock transcription factor HSF1 has a critical role in human epidermal growth factor receptor-2-induced cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2010;29(37):5204–5213. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciocca DR, Calderwood SK. Heat shock proteins in cancer: diagnostic, prognostic, predictive, and treatment implications. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2005;10(2):86–103. doi: 10.1379/CSC-99r.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulz R, Streller F, Scheel AH, et al. HER2/ErbB2 activates HSF1 and thereby controls HSP90 clients including MIF in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e980. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar S, Tomar MS, Acharya A. HSF1-mediated regulation of tumor cell apoptosis: a novel target for cancer therapeutics. Future Oncol. 2013;9(10):1573–1586. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carpenter RL, Paw I, Dewhirst MW, Lo HW. Akt phosphorylates and activates HSF-1 independent of heat shock, leading to Slug over-expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2015;34(5):546–557. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xi C, Hu Y, Buckhaults P, Moskophidis D, Mivechi NF. Heat shock factor Hsf1 cooperates with ErbB2 (Her2/Neu) protein to promote mammary tumorigenesis and metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(42):35646–35657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.377481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao YH, Zhou M, Liu H, et al. Upregulation of lactate dehydrogenase A by ErbB2 through heat shock factor 1 promotes breast cancer cell glycolysis and growth. Oncogene. 2009;28(42):3689–3701. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin X, Moskophidis D, Mivechi NF. Heat shock transcription factor 1 is a key determinant of HCC development by regulating hepatic steatosis and metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. 2011;14(1):91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen YF, Dong Z, Xia Y, et al. Nucleoside analog inhibits microRNA-214 through targeting heat-shock factor 1 in human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Sci. 2013;104(12):1683–1689. doi: 10.1111/cas.12277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chou SD, Murshid A, Eguchi T, Gong J, Calderwood SK. HSF1 regulation of beta-catenin in mammary cancer cells through control of HuR/elavL1 expression. Oncogene. 2015;34(17):2178–2188. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The random-effects sensitivity analysis of the OS.

Abbreviation: OS, overall survival.

Table S1.

Evaluations of the qualities of the included studies based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

| Author | Selection

|

Comparability

|

Outcome

|

Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Representativeness of the exposed cohort | 2) Selection of the nonexposed cohort | 3) Ascertainment of exposure | 4) Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study | 1) Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | 1) Assessment of outcome | 2) Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur | 3) Adequacy of follow up of cohorts | ||

| Tsukao et al1 | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 8 | |

| Liao et al2 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | ||

| Gokmen-Polar and Badve3 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | ||

| Santagata et al4 | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 8 | |

| Chuma et al5 | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 8 | |

| Zhang et al6 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7 | |

| Fang et al7 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | ||

| Zhou et al8 | * | * | * | * | * | 5 | |||

| Cui et al9 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7 | |

| Liang et al10 | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6 | ||

Note: The “*” denotes 1 point and “**” denotes 2 points.