Abstract

Patient-delivered partner therapy (PDPT) is the practice of providing patients diagnosed with a bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI) medication to give directly to their partner for treatment without requiring the partner to participate in diagnostic testing and counseling. Despite a growing body of evidence in support of PDPT, literature is limited to date on the influence of perceived risk of intimate partner violence (IPV) on PDPT use. We analyzed mixed-method data from 196 quantitative surveys (61% male, M age = 31.2, 92% Black or African American) and 25 qualitative interviews to better understand the barriers and facilitators associated with PDPT delivery for patients attending a Midwestern, publicly funded STI clinic. Nearly a third of surveyed patients (29%; 34% of women, 26% of men) expressed worry about IPV when delivering PDPT. Patients had concerns about infidelity worry, embarrassment, and anxiety (referred to as IWEA hereafter) associated with partner notification and PDPT delivery. We found IWEA was highly correlated with IPV concerns in a fully-adjusted logistic regression model. Women had 2.43 (95% CI = 1.09–5.42) times greater odds of worrying about IPV than men; other significant factors associated with IPV worry included higher condom use, no prior STI diagnosis, and being uninsured (as compared to having Medicare/Medicaid insurance). Encouraging communication between healthcare providers and their patients about the potential for IPV could facilitate patient triaging that results in the consideration of alternative partner referral mechanisms for patients or partners at risk of harm and better outcomes for patients and their partners.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, patient-delivered partner therapy, expedited partner therapy, partner notification, sexually transmitted infections

INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted infections (i.e., STIs) remain a preventable public health problem within the United States. Repeatedly acquired STIs are highly prevalent despite effective treatment options (Fung, Scott, Kent, & Klausner, 2007; Hosenfeld et al., 2009; Workowski, Bolan, & CDC, 2015), and mechanisms to increase partner notification are paramount to decreasing reinfections by reducing the risk of repeated exposure to an untreated partner. One mechanism to accelerate the time to partner treatment, increase partner treatment, reduce repeat infections, and reduce community prevalence of STIs is the use of patient-delivered partner therapy (PDPT) (Ferreira, Mathews, Zunza, & Low, 2013; Golden et al., 2015). PDPT is the practice of providing patients diagnosed with a bacterial STI medication to give directly to their partner for treatment without requiring the partner to participate in diagnostic testing, counseling, or an interaction with a healthcare professional. Despite a growing body of research in support of PDPT (Ferreira et al., 2013), further research is needed to identify barriers and facilitators of partner notification and PDPT delivery among STI clinic patients.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is one factor consistently associated with increased sexual risk behavior and HIV risk (Hess et al., 2012; Phillips et al., 2014; Seth, DiClemente, & Lovvorn, 2013), but literature is limited on the influence of IPV risk on partner notification. The reported prevalence of recently-experienced IPV among publicly funded STI or family planning clinic patients ranges from 11 to 28% (Decker et al., 2014; Mittal, Senn, & Carey, 2011; Senn, Walsh, & Carey, 2016), suggesting important service delivery implications for STI clinics. However, IPV is rarely assessed in the partner notification literature (Ferreira et al., 2013). Some studies have suggested that IPV may not be a major concern for patients delivering PDPT. For example, only 6% of patients enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of PDPT worried about the risk of violence associated with partner notification and PDPT delivery (Schillinger et al., 2003). Other researchers reported very rare occurrences of experiencing IPV when delivering PDPT to sexual partners (Temkin, Klassen, Mmari, & Gillespie, 2011), and only a few women worried about IPV associated with patient-delivered STI screening kits in another study (McBride, Goldsworthy, & Fortenberry, 2010). These prior estimates are limited by methods of data collection. Most qualitative studies had limited sample sizes by design and could not provide an empirical assessment of risk (McBride et al., 2010; Temkin et al., 2011), and quantitative studies with individuals willing to enroll in a randomized controlled trial of PDPT may not be generalizable to the entire STI clinic patient sample (Schillinger et al., 2003).

A significant gap in the literature exists regarding the influence of IPV on partner notification and PDPT. In contrast to past research that focused on previous experiences of IPV victimization in conjunction with partner notification (Decker et al., 2014), we focused on patients’ future anticipations of IPV. Patients may worry about potential IPV, despite limited prior victimization. Since PDPT is now considered standard practice (Workowski et al., 2015) and further rollout is a public health goal, understanding factors that may limit patient willingness – as well as threaten patient wellbeing – require further study. Therefore, the overall goal of this research was to identify and assess patients’ prospective worries about IPV associated with partner notification and PDPT delivery to inform future intervention development.

METHODS

Recruitment

Adult (18+ years old) patients from a large, publicly funded STI clinic in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, were recruited to participate in a mixed-method study on PDPT between March and June 2016. All patients 18 years of age or older were eligible to participate in this study, and nominal cash incentives were offered for participation. Recruitment occurred in three phases by design. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Phase 1

Five clinic patients were qualitatively interviewed using a semi-structured interview guide on barriers and facilitators of hypothetical PDPT delivery to identify thematic trends and develop instrument questions for a quantitative survey. Initially, 11 clinic patients were approached and screened for their eligibility to participate in the first phase of qualitative interviewing. One person declined to be screened, and the remaining 10 patients were screened and met the eligibility requirements. Three eligible participants declined enrollment, and two agreed but did not attend their scheduled appointments. A final sample of five patients (the target sample size) enrolled in this phase of the study. A convenience sampling strategy was used and resulted in a sample that matched the clinic demographic characteristics for gender and race. Three men and two women enrolled in the study, and four of the five participants were Black or African American. Mean age of the Phase 1 sample was 30 years old, and four of five participants were 20–30 years old. Two of the participants were at the clinic on the day screened for contact with someone diagnosed with an STI, while the other three presented for a regular STI screening (“checkup”). First-choice preference for partner notification was variable, with two patients preferring medication delivery (PDPT), one prescription delivery, and one simple partner referral without medication or prescription; one patient had no interest in notifying his partner.

Phase 2

In Phase 2, five more clinic patients were interviewed using a highly-structured interview guide to determine the content validity of the survey items generated in Phase 1 using a “think aloud” approach (Collins, 2003; Willis, 2005). This method encourages respondents to verbalize how they interpret questions and map their responses to quantitative survey items. Participants were also allowed to freely vocalize their opinions in response to survey questions in the spirit of qualitative inquiry, which provided narrative used for analysis. Initially, 23 clinic patients were invited to participate in this phase of the study. Three patients declined screening, and 20 individuals agreed, were screened, and met eligibility criteria. Post screening, eight declined to participate, one agreed then later declined, and six agreed but did not attend the interview, leaving a final sample of five individuals (the target sample size) participating in the cognitive interview. Enrolled participants had a mean age of 34 years old. Four men and one woman participated, all participants were Black or African American, and one was of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity. Of the five patients enrolled in Phase 2, four of them presented at the clinic with symptoms of an STI and one for a regular STI screening. First-choice preference for partner notification stated during screening was medication delivery (PDPT) for one participant, prescription delivery for two, and simple partner referral without medication or prescription for the final two. Based on the results of these cognitive interviews, the survey questionnaire was revised and finalized.

Phase 3a

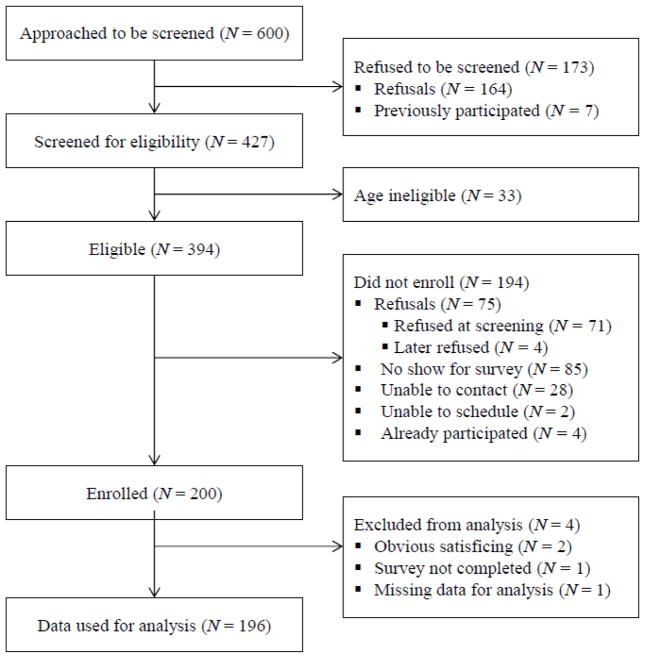

Six-hundred STI clinic patients were invited to be screened for their eligibility to participate in the Phase 3a survey. Of the 600 patients approached in the clinic, 173 declined to be screened for the research study. The remaining 427 patients were screened for eligibility, and 394 patients were eligible to participate in the survey. Of these 394 patients, 71 declined to participate in the study at the time of screening, four declined participation after being screened, 85 did not attend the scheduled survey appointment, 30 were not available, and four were ineligible due to previous enrollment. This resulted in an enrolled sample of 200 STI clinic patients. Of screened participants, no significant differences were found between those who enrolled and those who did not in demographic characteristics, reason for STI clinic visit, or first-choice preference for partner notification. After excluding data from four participants because of obvious satisficing (Krosnick, 1991) or incomplete data, a final sample of N=196 patients was used for quantitative analysis (see Figure 1 for the full enrollment flow diagram). Demographic and background characteristics of the final sample used for analysis are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Enrollment Flow Diagram for Phase 3 Mixed-Method Study

Table 1.

Demographics, behavioral characteristics, and worry of intimate partner violence among STI clinic patients (N = 196)

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, M (Mdn), SD | 31.2 (27) | 11.5 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 119 | 60.7 |

| Female | 77 | 39.3 |

| Race | ||

| Black or African American | 180 | 91.8 |

| White | 9 | 4.6 |

| Other race | 16 | 8.2 |

| Hispanic/Latino Ethnicity | 14 | 7.1 |

| Education | ||

| Some high school, no diploma | 32 | 16.3 |

| High school diploma or GED | 84 | 42.9 |

| Some college or more | 80 | 40.8 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-time | 57 | 29.1 |

| Part-time | 47 | 24.0 |

| Unemployed | 92 | 46.9 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single – never married, not living with significant other | 123 | 62.8 |

| Never married, living with significant other | 48 | 24.5 |

| Married | 9 | 4.6 |

| Divorced | 14 | 7.1 |

| Widowed | 2 | 1.0 |

| Insurance Status/Type | ||

| Private | 21 | 10.7 |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 106 | 54.1 |

| Uninsured | 55 | 28.1 |

| Other, don’t know, or missing | 14 | 7.1 |

| Reason for STI Clinic Visit (select all that apply) | ||

| Symptoms of an STI | 55 | 28.1 |

| Contact with someone diagnosed with an STI | 30 | 15.3 |

| Treatment after positive test | 10 | 5.1 |

| Regular STI screening (“checkup”) | 103 | 52.6 |

| Other reason | 11 | 5.6 |

| Prior STI Diagnosis | ||

| No prior STI diagnosis | 61 | 31.1 |

| Prior STI, no partners notified | 21 | 10.7 |

| Prior STI, at least some partners notified | 114 | 58.2 |

| Number of Sexual Partners (Past 90 Days) | ||

| Zero or 1 partners | 89 | 44.9 |

| Two or more partners | 108 | 55.1 |

| Condom Use (Past 90 Days) | ||

| Every time | 21 | 10.7 |

| Most of the time | 49 | 25.0 |

| Sometimes | 64 | 32.7 |

| Never | 62 | 31.6 |

| Infidelity Worry, Embarrassment, and Anxiety (IWEA), M, SD | 3.3 | 1.1 |

| Self-Reported Worry of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) | n | % |

|

| ||

| IPV Worry (total) | 57 | 29.1 |

| Men | 31 | 26.0 |

| Women | 26 | 33.8 |

Phase 3b

Finally, 15 survey respondents – a subsample of the 196 survey participants used for analysis – were purposively sampled for in-depth qualitative interviewing to identify potential intervention mechanisms, barriers and facilitators to PDPT delivery, and other important information for planning a randomized controlled trial. Heterogeneous, purposive sampling – a method that permits investigators to select a heterogeneous sample (Ritchie, Lewis, Elam, Tennant, & Rahim, 2013) was used to select a sample that was balanced in terms of sex, race, and ratings of PDPT acceptability. After an initial random sample of survey participants, recruiting a roughly equal distribution of men and women, oversampling of women was required because of the lower number of women participating in the survey that reflects the STI patient demographic. Similarly, following the initial random sample, survey data was filtered by PDPT acceptability responses to assure recruitment of a roughly equal distribution of high, medium, and low PDPT acceptors.

Measures

Demographics and sexual behaviors

Participants were asked about their demographics, including age, sex assigned at birth, race, ethnicity, relationship status, education level, employment status, and insurance status. Participants were also asked about the reason for their current clinic visit, STI treatment and partner notification history, number of sexual partners (past 90 days), and recent condom use (past 90 days).

Infidelity worry, embarrassment, and anxiety

Based on responses from qualitative interviews conducted at Phase 1, a scale was developed to measure infidelity worry, embarrassment, and anxiety (IWEA) associated with partner notification. The single-construct grouping of scale items is based on potential IPV triggers (i.e., perceived unfaithfulness and potential for arguments) and patients’ worries associated with IPV triggers (i.e., embarrassment and awkwardness associated with perceived infidelity, and perceptions of a stressful situation). Five-point response categories for IWEA items ranged from very untrue of what I believe to very true of what I believe. The 6-item IWEA scale demonstrated good reliability in our survey sample (Cronbach’s alpha = .83), and a factor analysis showed that the scale was unidimensional. We used principal axis factoring with oblique promax rotation (see Table 2 for scale items and factor loadings).

Table 2.

Infidelity worry, embarrassment, and anxiety associated with partner notification (IWEA) scale items and factor loadings

| Scale Items1 | Factor Loadings2 |

|---|---|

| 1. I would be embarrassed to tell my partner(s) that I have an STI. | 0.66 |

| 2. I am worried my partner(s) might think I have been unfaithful if I am diagnosed with an STI. | 0.56 |

| 3. I worry what my partner(s) will think if I tell them I have an STI. | 0.78 |

| 4. Telling my partner(s) about my STI would be stressful. | 0.74 |

| 5. Telling my partner(s) about my STI would be awkward. | 0.75 |

| 6. Telling my partner(s) about my STI would cause an argument. | 0.57 |

Note:

response categories: “very untrue of what I believe” to “very true of what I believe;”

factor maxtrix loadings using principal axis factoring

Perceptions of risk for intimate partner violence

Perceived risk of IPV associated with PDPT was assessed with one item: “I worry about my safety notifying my partner(s) of an STI.” Response categories from very untrue of what I believe to very true of what I believe were dichotomized; those who responded true or very true of what I believe were coded as being at risk of IPV, whereas lower scores were coded as not at risk of IPV.

Data Analysis

Quantitative analyses

Based on the responses obtained from the survey, univariate, descriptive statistics on demographics, behavioral characteristics, and IPV risk were compiled. Logistic regression was then used to test bivariate and multivariate predictors of IPV risk. We report both unadjusted and fully-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Qualitative analysis

The purpose of the Phase 1 interviews was to identify potential responses and theoretical constructs to be used within the quantitative survey that may not have been identified based on a literature review alone. One-on-one qualitative interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended interview questions developed based on themes identified within extant literature on PDPT use and an adaptation of the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model (Fisher & Fisher, 1992). As such, participants were given a brief overview about PDPT and then asked open-ended questions aligned with IMB model constructs (i.e., information, attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioral skills). More general questions were also asked, given the exploratory nature of this research [e.g., “Beyond what you’ve already told me, what might get in the way of you being able to deliver medications for you to treat your sexual partner(s)?”]. These questions allowed further inductive inquiry. In Phase 2, participants provided responses during the cognitive interview, and probing questions [e.g., “Tell me more (about …)”] were used to elicit more in-depth narrative; both types of responses were included in analyses. Finally, Phase 3b semi-structured interviews elicited barriers and facilitators to partner notification and PDPT delivery [e.g., “What might stand in the way of your success in providing medications for you to give to your sexual partner(s)?”]. Average interview length was 48, 99, and 46 minutes for Phase 1, 2, and 3b interviews, respectively.

Thematic content analysis was used to inductively identify themes relevant to patients’ worries about IPV with partner notification. Qualitative data from Phases 1, 2, and 3b were transcribed verbatim before undergoing analysis. Data from all three qualitative phases were aggregated to allow an adequate sample size valid for qualitative inquiry (Ritchie et al., 2013). Data analysis was conducted by the first author using an iterative process, including post-interview written reflections and thematic notes, transcription quality assurance, identification of initial themes, re-recoding of transcripts after codebook refinement, and extraction of quotes and input into a framework matrix. Microsoft Excel was used for the framework approach to data analysis (Spencer, Ritchie, O’Connor, Morrell, & Ormston, 2013), allowing within- and between-participant analyses of quotations arranged by theme to more fully account for similarities and differences across interviewees. Quotes representative of resultant major themes were then selected for use as evidentiary illustrations of the findings.

RESULTS

Quantitative Results

In total, data from 196 survey respondents and 25 interviews (both semi-structured and cognitive interviews) were included in analyses. Empirical data provide information on the pervasiveness of IPV risk among STI clinic patients. Overall, 29% of patients had some degree of worry about their safety when notifying a partner of an STI. More specifically, 34% of women and 26% of men reported IPV risk. Results of the fully-adjusted logistic regression model assessing demographic and behavioral characteristics associated with IPV risk are presented in Table 3. The likelihood ratio test was statistically significant [LR χ2(24) = 37.51; p=0.04; pseudo R2 = 0.159), suggesting statistically significant predictors in the model. Briefly, the odds of women worrying about IPV were 2.43 (95% CI = 1.09–5.42) times greater than for men in the fully-adjusted model. Patients on Medicare or Medicaid were less likely to be worried about IPV as compared to those who were uninsured (OR = 0.37; 95% CI = 0.15–0.93). Those without a prior STI diagnosis were more likely to perceive IPV risk as compared to those with prior diagnoses who notified some partners (OR = 2.38; 95% CI = 1.05–5.40). More frequent condom use was associated with increased odds of worrying about IPV, where a one unit increase in condom use (e.g., never to sometimes) was associated with 65% greater odds (OR = 1.65; 95% CI = 1.08–2.52) of IPV worry. Finally, a one unit increase in perceiving infidelity worry, embarrassment, or anxiety related to partner notification was associated with 55% greater odds of worrying about IPV (OR = 1.55; 95% CI = 1.07–2.25).

Table 3.

Logistic regression odds ratios of demographic and behavioral characteristics on worry about intimate partner violence among a sample of STI clinic patients (N = 196)

| Variable | Unadjusted | Adjusted |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% C.I.) | OR (95% C.I.) | |

| Age | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1.45 (0.77–2.70) | 2.43 (1.09–5.42)* |

| Male | Reference | Reference |

| Race | ||

| Black or African American | 0.89 (0.30–2.70) | 0.43 (0.04–4.74) |

| White | 1.23 (0.30–5.10) | 0.64 (0.05–7.91) |

| Other race | 0.80 (0.25–2.59) | 0.43 (0.06–3.02) |

| Hispanic/Latino Ethnicity | 0.97 (0.29–3.24) | 1.01 (0.22–4.68) |

| Education | ||

| Some high school, no diploma | 1.07 (0.44–2.59) | 1.60 (0.59–4.31) |

| High school diploma or GED | Reference | Reference |

| Some college or more | 0.90 (0.45–1.76) | 0.83 (0.37–1.86) |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-time | 1.02 (0.50–2.11) | 0.82 (0.33–2.06) |

| Part-time | 0.92 (0.42–2.01) | 0.63 (0.25–1.61) |

| Unemployed | Reference | Reference |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single – never married, not living with significant other | 0.83 (0.44–1.56) | 0.73 (0.34–1.57) |

| Other – living with sig. other, married, divorced, or widowed1 | Reference | Reference |

| Insurance Status/Type | ||

| Private | 0.65 (0.22–1.93) | 0.53 (0.14–2.01) |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 0.55 (0.28–1.11) | 0.37 (0.15–0.93)* |

| Uninsured | Reference | Reference |

| Other, don’t know, or missing | 0.44 (0.11–1.77) | 0.52 (0.10–2.70) |

| Reason for STI Clinic Visit (select all that apply) | ||

| Symptoms of an STI | 0.52 (0.24–1.09) | 0.90 (0.19–4.35) |

| Contact with someone diagnosed with an STI | 0.71 (0.28–1.75) | 0.81 (0.15–4.48) |

| Treatment after positive test | 1.05 (0.26–4.20) | 0.94 (0.12–7.23) |

| Regular STI screening (“checkup”) | 2.28 (1.20–4.33)* | 1.57 (0.34–7.15) |

| Other reason | 0.53 (0.11–2.51) | 0.28 (0.03–2.53) |

| Prior STI Diagnosis | ||

| No prior STI diagnosis | 3.02 (1.54–5.91)** | 2.38 (1.05–5.40)* |

| Prior STI, no partners notified | 0.84 (0.26–2.72) | 0.93 (0.25–3.46) |

| Prior STI, at least some partners notified | Reference | Reference |

| Number of Sexual Partners (Past 90 Days) | ||

| Zero or 1 partners | Reference | Reference |

| Two or more partners | 1.44 (0.77–2.70) | 1.75 (0.79–3.85) |

| Condom Use (Past 90 Days)2 | 1.37 (1.00–1.88)* | 1.65 (1.08–2.52)* |

| Infidelity Worry, Embarrassment, and Anxiety (IWEA) | 1.56 (1.15–2.12)** | 1.55 (1.07–2.25)* |

Notes:

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

collapsed categories for logistic regression analyses

continuous measure of condom use used for logistic regression analyses

Findings from Qualitative Interviews

Main findings presented within this analysis are separated into four thematic sections: 1) infidelity worry, embarrassment, and anxiety; 2) risk of violence; 3) preparing patients for an unforeseen circumstance; and 4) potential for patient triaging based on IPV risk. Each quote is labeled with the participant’s age, race (B = Black or African American; W = White; M = Multicultural), and gender (M = man; W = woman) in that order within their abbreviation. For example, a 58 year old White man is referred to as 58WM, a 21 year old Black woman is referred to as 21BW, and when two or more participants had the same demographics they are referred with a secondary numerical label to allow delineation (e.g., 25BM-1; the first 25 year old Black man interviewed).

Infidelity worry, embarrassment, and anxiety

Participants thought critically about how their partner might respond to being notified of the STI and given medications. Participants worried about the implications of infidelity, feeling embarrassed, and anxiety over how their partner might respond to notification of the STI exposure.

There is that obvious stigma of having that sexually transmitted disease because that means you were being unfaithful. (24BW)

They’re basically probably just too embarrassed to deliver medications to their partner. (21BW)

It’s difficult to tell them because you’re afraid of their reaction. (22BM)

Participants discussed the assumptions of infidelity related to an STI diagnosis, and this caused some to feel embarrassed about delivering medications to their partner. Participants worried about how their partners would react when they notified them of the STI, and this worry was perceived to be a large barrier to partner notification and PDPT delivery. More severe worries about the risk of IPV were mentioned by participants and discussed next.

Risk of violence

Participants – both men and women – were concerned about the potential for violence when notifying their partner of an STI. This prominent theme was discussed on the continuum of verbal abuse to murder in conjunction with patients telling their partners about the STI.

Ain’t no telling what she might do (in heavier tone) … The reactions can be all types of stuff. It can be - it can leads to an argument, it can leads to a fight, and also can leads to death. … It can leads to ending the relationship. It can, depending on the type of person you talking to (in heavier tone), it can also land on a lot of other mess like fights and a person might feel some type of way and kill you. (29BM)

Whether it be the person has also themselves been infected or not, just the fact of not knowing and being so insecure or so uncomfortable would possibly potentially cause arguments, possible fights, maybe even some type of jail time. (32MM)

I think [intimate partner violence is] more common than not. I mean, I myself have had some situations in the past where I’ve been with someone who was kind of violent, but I’ve gotten away from it because that’s not something that I would like to live with and that’s not something I’m willing to endure. … I’ve seen young people, younger people now today are getting into more domestic disputes than not. I have younger brothers and they both have been in domestic situations with their girlfriends and whatnot. … I see it more prevalent than not in the younger generation like this is something that they think is okay or is something that, oh, it’s just if a person doesn’t, if they don’t slap you or kick you or punch you, they don’t love you. (35BW)

The type of partnership mattered in the context of IPV risk. Mainly, the risk of violence was thought to be less for more serious, long-term relationships.

Some stranger and we [are] still talking; I don’t think I would tell [them about the STI]. … I don’t know the person. … And they could be violent or come at you. … But a long-term, yes, but … a short-term, I would be less eager to do this. (58WM-2)

Others discussed their own worries or thoughts about violence against their partner. Participants were open about these worries, and discussed the type of internal monologue they might have to fight off these violent urges.

It’d be so crazy cuz the results come back and they say this and they say that – all type of thoughts runs through your head about everything. Wanting to hurt the person, [wanting] to find the person who gave it to her, but you might not know if he gave it to her or he gave it to her. It’s a lot of thoughts that run through your head. You might want to choke her up, slap her out or – it’s a disa… [/disaster/] – it’s a thought process. But, the only way you can fight them thoughts away is to get yourself cured and never do it again. Like I said, everything is a lesson learned. (29BM)

I don’t remain calm, I go off the wagon when something pertaining to my health is at risk because of somebody else’s carelessness. (47BW)

I would have wanted to [take meds] to him. … I probably would have like physically gave it to him in the sense, I probably would have hit him with the bottle upside his head or something, but he would have got his treatment. (28BW)

Preparing patients for an unforeseen circumstance

Understanding the severity of IPV, participants offered suggestions for patients and healthcare providers to address the risk of violence. These suggestions included better preparing patients for adverse events, allowing patients to tell their partners with healthcare providers present, and screening for IPV before considering a partner referral strategy.

[Patients] have to understand the fact that [their partner] may or may not take this in any type of way that it may go a different direction than you’re thinking it will go. (24BW)

[If there is a risk of violence between partners,] call you and your partner in but put you guys in separate rooms and [have a healthcare provider] talk to each individual like a one-on-one. (28BW)

If you’ve had a violent relationship and then you have to tell something like this, that would probably be a question [healthcare providers should] ask in regards when a person is coming to get treatment and you give them the medication. Okay, ask them about their relationship. Is it a violent relationship? Are you safe in the relationship? Would you feel comfortable actually telling a person? You know, because sometimes they may not be. And then that way it can be handled by the healthcare provider or the facility in order to get in contact with this person. … You can allow us to do that. Here’s how we’re going to do this. We’re going to give you information. We can give you information about referrals to go to get help for domestic violence and whatnot. (35BW)

Patients discussed the difficulty in telling a healthcare provider about their violent partner. These difficulties extended to reporting IPV after an incident because of distrust in the police, where victims of violence may not want to report an incident because of fear the police will blame them.

It would be kind of hard to do because how would they know what to do, how would they know to deal with this person if the patient can’t even tell the health provider to tell this person because the person would be more or less like how did they know about me and why did you tell them about me and about my situation. That would be kind of hard. … I wouldn’t provide his information like that. … If I was scared of my partner, I wouldn’t have, I wouldn’t give his information like that. (44BW)

[If it didn’t go as planned,] I might have to call the police and leave. (19BW)

Scared they going to get beat up. … [I worry] for a lot of people. … [and] when I call the police, they going to tell me I’m the problem. (42BW)

Potential for patient triaging based on IPV risk

One patient thought of mechanisms to handle situations in which violence between partners could be evident. Triaging patients based on IPV risk was considered a potential mechanism for identifying patients who shouldn’t receive PDPT, but could benefit from alternative methods of partner referral.

[If there is a risk of violence,] they should have that person get that person’s name or telephone number. … [The clinic] would contact them totally anonymous, not tell them that you told us, but … [the clinic would tell them that they] need to come to this such and such health place and [to get] treatment. … Maybe if they felt safer doing it in the actual clinic, maybe calling that person and having them meet them there. (35BW)

While provider referral and disclosure with a healthcare provider present were two recommended strategies, these methods would not reduce the risk of IPV after the patient leaves the clinic. Others did not have ideas for a solution to partner treatment when IPV is an issue, suggesting the difficulty in navigating partner notification when risks of IPV are evident.

DISCUSSION

Fear of violence when notifying a partner of an STI was a salient theme among both men and women in a sample of patients from a public, urban STI clinic. Patients discussed their worry about the potential for arguments, fights, and murder when notifying partners of an STI. Twenty-nine percent of the surveyed patients had some degree of worry about their safety when notifying a partner. Participants discussed the context of this worry in detail by describing how situations could escalate quickly and trigger violent situations, especially given implications of infidelity and STI responsibility or blame. While participants worried about their partners being violent, some discussed their own struggle to handle their emotions. One man discussed his internal monologue about wanting to potentially hurt his partner or the person that gave her the STI, but he also discussed trying to fight these thoughts away. Another patient discussed her worries about her inability to remain calm when issues pertaining to her health are evident.

Our findings support prior research that IPV is a prevalent issue and concern for STI clinic patients, yet these results provide further impetus to increase the attention given to IPV risk specifically associated with PDPT and other methods of partner notification. Past studies about PDPT likely underreport the true IPV risk for patients because of study design. When studying the potential of patient-delivered STI screening kits in another study, fear of a partner’s reaction was an important barrier to delivering the screening kit; however, risk of violence was only mentioned by a very small proportion of women (McBride et al., 2010). In another STI clinic sample, one participant reported a violent reaction upon providing his partner the medications, which resulted in verbal and physical assault (Temkin et al., 2011). Some have suggested that the provision of the physical medications results in an appraisal of “reality” of the STI (McBride et al., 2009; Young et al., 2007), which could heighten risks of IPV. Despite 6% of women reporting worry about violence within one randomized controlled trial of PDPT, no adverse events were reported by study completion (Schillinger et al., 2003). Two of the previous studies were qualitative inquiries (McBride et al., 2010; Temkin et al., 2011), which do not garner sufficient data to provide an empirical assessment of IPV risk. The one quantitative study (Schillinger et al., 2003) did have a large survey sample to measure the potential risk of IPV, yet individuals who enrolled in the randomized controlled trial about PDPT may not be generalizable to all STI clinics. Individuals at risk of IPV may avoid enrolling in a study where they may have to participate in PDPT due to concerns about their partners’ reactions.

Our mixed-method study design allowed us to maximize the benefits of both qualitative and quantitative data and crosscheck the context of our findings. Patients only had to consider PDPT under a hypothetical scenario, which increases the potential generalizability of our findings. Despite prior reports of limited IPV risk, 29% of participants within our Midwestern STI clinic sample and over one in three women surveyed had some degree of worry, suggesting the importance of identifying patients at risk of violence before recommending any partner referral mechanism that could result in harm for the patient or their partner. One study found nearly a third of healthcare providers had not thought about the possible link between IPV and STIs (Rosenfeld et al., 2016), indicating that outreach to healthcare providers may be needed to increase awareness of the potential for IPV when a patient notifies a partner of an STI and/or delivers PDPT.

As a salient theme in interviews and a highly prevalent worry among survey respondents, addressing the risk of violence is an utmost priority. The mixed-method study design allowed us to specifically ask participants what could be done to minimize these risks if they mentioned them as potential barriers to PDPT delivery. One mechanism identified by a participant to address this issue was to triage patients at risk of IPV to alternative methods of partner referral. This would require healthcare providers to have conversations with each patient to identify any potential risk of harm to the patient or their partner. If a patient felt unsafe notifying the partner themselves, which is central to PDPT, an alternative partner referral mechanism could be considered, such as provider referral. An alternative to having a healthcare provider call the partner directly was to have the partner come to the clinic where the patient or healthcare provider could tell the partner in a safer environment. However, neither of these alternatives reduces the risk of violence after the clinic visit without additional intervention. Future mixed-methods research is needed to identity the best strategies for partner notification among those at risk of IPV.

Healthcare providers are responsible for preparing patients to notify their partner of an STI, including preparing them for unforeseen circumstances. Patients described the importance of understanding that the interaction with their partner might not go as planned, and they need to be prepared for a negative response. This is particularly important for patients notifying casual partners, as participants described not knowing how these partners might respond to PDPT. Future interventions are needed targeting IPV as a central issue, including developing behavioral skills for patients to help them avoid and handle situations in which a negative partner response is encountered. Incorporating role-playing exercises into patient counseling is one mechanism to better prepare patients with the skills needed for partner notification and PDPT delivery that should be explored in future interventions.

We found several factors to be associated with IPV worry in our study. Patients who reported condom use in the past 90 days were more likely to be worried about IPV. This finding diverges from previous literature, which found a negative association between IPV victimization and condom use (Decker et al., 2014; Hess et al., 2012; Mittal et al., 2011). However, in our study, condom use frequency may be a proxy for relationship type; patients with less condom use could be in more serious relationships (Senn, Carey, Vanable, & Coury-Doniger, 2010). In our patient interviews, participants were less worried about IPV with long-term partners, providing plausibility to this proxy measurement. However, this was only somewhat supported by our post-hoc analyses looking at condom use as the outcome variable; we conducted a secondary, multiple linear regression model to test correlates of relationship proxy variables (i.e., relationship status, having two or more recent sexual partners in the past 90 days, and IWEA) and IPV worry on condom use, controlling for demographic variables (i.e., age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, employment, and insurance status). We hypothesized that those with more casual relationships might both worry more about IPV in the context of PDPT and use condoms more frequently. As expected, the results of these analyses showed that those who were single used condoms more frequently (b = 0.40, p ≤ 0.01); additionally, having two or more partners was marginally associated (b = 0.24, p < 0.10) with condom use. Individuals with higher infidelity worry, embarrassment, and anxiety about partner notification reported significantly less frequent condom use (b = −0.16, p ≤ 0.05). However, even after controlling for these relationship variables, IPV worry was still associated with more frequent condom use in the past 90 days (b = 0.39, p ≤ 0.05), suggesting this effect is likely not the result of a third, unmeasured variable of relationship closeness or that we lack a proper measure (e.g., commitment measure or relationship length). It is important to note that we attempted to measure prospective worry about IPV, not prior IPV victimization, which complicates comparison of our findings to previous literature. Nonetheless, further research is needed to understand the association between condom use and IPV worry with STI partner notification.

A prior STI diagnosis with at least some partners notified was associated with less IPV worry, potentially because of experiential learning. Patients could be less worried about IPV because of a previous encounter notifying a partner that did not result in violence. Patients on public insurance had less worry about the potential for IPV than those uninsured. No difference was found between patients with private insurance and those without any insurance, possibly because of the relatively small sample size of patients who had private insurance. Insurance status may be a good indicator of access to services and structural social support for the patient. Reinforcing efforts to promote connecting patients seen at free, public STI clinics to public insurance and other mechanisms of structural support is needed, particularly important given quotes about IPV victims’ unwillingness to report incidents because of distrust in the police.

In this mixed-method study, we developed the IWEA (i.e., infidelity worry, embarrassment, and anxiety of partner notification) scale that demonstrated good psychometric properties. The IWEA demonstrated good reliability and measured a unidimensional construct associated with IPV worry. Patients with higher IWEA were more likely to report IPV concerns. This finding is noteworthy because it offers another avenue to identify patients at risk of IPV, wherein healthcare providers can ask about the patients’ concerns of IWEA leading into their assessment of IPV risk. Since this is a significant predictor of IPV, providers need to pay more attention to patients’ questions that are indicative of IWEA when they interact with their patients. Identifying and addressing IPV should be considered within all STI clinics where potential clinical care recommendations can be effectively provided. These clinics may offer a linkage-to-care access point for patients with limited resources, especially relevant since patients on Medicare or Medicaid were less likely to report IPV worry compared to those without insurance. Researchers and clinicians developing educational or skills-based trainings to increase patients’ confidence and intentions in providing PDPT to their partners must also be cognizant of patients’ IPV concerns.

Limitations

Several limitations of this research study merit mention. First, all data were self-reported. While we used a self-administered survey assessment procedure, and took steps to minimize demand effects and maximize candid responses, the potential for response bias cannot be ruled out. Response bias would likely result in under-reporting of IPV concern; the prevalence of IPV worry could thus be even higher than reported. Second, we experienced a high rate of no-shows for interviews during Phase 2; the higher no-show rate for this phase could be the result of the larger time commitment required for participation in this extensive interview. Third, the risk of IPV was only one barrier of many associated with hypothetical PDPT delivery, limiting the exploration of this theme in greater detail with more extensive probing questions during qualitative interviews. Nonetheless, this research identified a significant barrier to full PDPT uptake within local STI clinics. Further research is needed to promote safe and effective use of PDPT and other partner notification services for STI clinic patients.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we found IPV to be a pervasive worry among STI clinic patients, which was a substantial barrier to partner notification and PDPT delivery. Patients reported worries about infidelity implications, embarrassment associated with the STI, and anxiety related to partner notification and PDPT delivery. Patients with a prior STI were less likely to report IPV worry, but patients with more condom use worried about IPV more. Uninsured patients were also more likely to report IPV worry compared to patients on Medicare or Medicaid. This research identified a significant proportion of STI clinic patients who may not be ideally suited for PDPT, which could prevent full implementation within some STI clinic settings. Further mixed-method research is urgently needed to prepare patients for partner notification and PDPT delivery while understanding and assisting patient navigation of IPV risks associated with this behavior. Encouraging communication between healthcare providers and their patients about the potential for IPV could facilitate patient triaging that results in the consideration of alternative partner referral mechanisms for patients or partners at risk of harm and better outcomes for patients and their partners.

Acknowledgments

Funding support was provided from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH089129; PI: Weinhardt; K01-MH099956; PI: Walsh) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA036466; MPIs: Parsons and Grov), which supported several authors of this study. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional funding support came from the Public Health Doctoral Student Award (PI: John) from the Dean’s Office in the Zilber School of Public Health at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. This award provided funding for a large portion of the direct research costs associated with this study.

We would like to thank the additional contributors of this study. First and foremost, we want to thank the many clinic patients who participated in this study; this research would not have been possible without their valuable contributions. Thank you to Katie Mosack, who provided valuable feedback on the qualitative methods of this study and earlier revisions of this manuscript. Thank you to Ron Cisler, who provided conceptual feedback when this study was in its infancy. We would also like to thank the Undergraduate Research Assistants who helped with recruiting study participants and data collection, including Katelyn Dallman, Amie Emrys, Ratka Galijot, and Steven Lovejoy, in alphabetical order. Finally, we want to thank the entire City of Milwaukee Health Department staff, who helped provide an atmosphere supportive of research and data collection within their clinic space, especially Paul Hunter, Irmine Reitl, and Otilio Oyervides.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Collins D. Pre-testing survey instruments: An overview of cognitive methods. Quality of Life Research. 2003;12(3):229–238. doi: 10.1023/A:1023254226592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MR, Miller E, McCauley HL, Tancredi DJ, Levenson RR, Waldman J, … Silverman JG. Intimate partner violence and partner notification of sexually transmitted infections among adolescent and young adult family planning clinic patients. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2011;22(6):345–347. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2011.010425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MR, Miller E, McCauley HL, Tancredi DJ, Anderson H, Levenson RR, Silverman JG. Recent partner violence and sexual and drug-related STI/HIV risk among adolescent and young adult women attending family planning clinics. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2014;90(2):145–149. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A, Young T, Mathews C, Zunza M, Low N. Strategies for partner notification for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;10:CD002843. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002843.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111(3):455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung M, Scott KC, Kent CK, Klausner JD. Chlamydial and gonococcal reinfection among men: A systematic review of data to evaluate the need for retesting. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2007;83(4):304–309. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.024059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden MR, Kerani RP, Stenger M, Hughes JP, Aubin M, Malinski C, Holmes KK. Uptake and population-level impact of expedited partner therapy (EPT) on chlamydia trachomatis and neisseria gonorrhoeae: The Washington state community-level randomized trial of EPT. PLoS Medicine. 2015;12(1):e1001777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess KL, Javanbakht M, Brown JM, Weiss RE, Hsu P, Gorbach PM. Intimate partner violence and sexually transmitted infections among young adult women. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2012;39(5):366–371. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182478fa5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosenfeld CB, Workowski KA, Berman S, Zaidi A, Dyson J, Mosure D, … Bauer HM. Repeat infection with chlamydia and gonorrhea among females: A systematic review of the literature. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2009;36(8):478–489. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a2a933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick JA. Response strategies for coping with the cognitive demands of attitude measures in surveys. Applied cognitive psychology. 1991;5(3):213–236. [Google Scholar]

- McBride KR, Goldsworthy RC, Fortenberry JD. Patient and partner perspectives on patient-delivered partner screening: Acceptability, benefits, and barriers. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2010;24(10):631–637. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride K, Goldsworthy RC, Fortenberry JD. Formative design and evaluation of patient-delivered partner therapy informational materials and packaging. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2009;85(2):150–155. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.033746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal M, Senn TE, Carey MP. Mediators of the relation between partner violence and sexual risk behavior among women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2011;38(6):510–515. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318207f59b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DY, Walsh B, Bullion JW, Reid PV, Bacon K, Okoro N. The intersection of intimate partner violence and HIV in U.S. Women: A review. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2014;25(1):S36–S49. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J, Lewis J, Elam G, Tennant R, Rahim N. Designing and Selecting Samples. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nicholls CM, Ormston R, editors. Qualitative research practice. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc; 2013. p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld EA, Marx J, Terry MA, Stall R, Pallatino C, Borrero S, Millwer E. Intimate partner violence, partner notification, and expedited partner therapy: A qualitative study. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2016;27(8):656–661. doi: 10.1177/0956462415591938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillinger JA, Kissinger P, Calvet H, Whittington WL, Ransom RL, Sternberg MR, … Fortenberry JD. Patient-delivered partner treatment with azithromycin to prevent repeated chlamydia trachomatis infection among women: A randomized, controlled trial. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2003;30(1):49–56. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA, Coury-Doniger P. Partner dependence and sexual risk behavior among STI clinic patients. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2010;34(3):257–266. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2010.34.3.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Walsh JL, Carey MP. Mediators of the relation between community violence and sexual risk behavior among adults attending a public sexually transmitted infection clinic. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2016;45(5):1069–1082. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0714-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, DiClemente RJ, Lovvorn AE. State of the evidence: Intimate partner violence and HIV/STI risk among adolescents. Current HIV Research. 2013;11(7):528–535. doi: 10.2174/1570162x12666140129103122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer L, Ritchie J, Ormston R, O’Conner W, Barnard M. Analysis: Principles and Processes. In: Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nicholls CM, Ormston R, editors. Qualitative research practice. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc; 2013. p. 269. [Google Scholar]

- Temkin E, Klassen AC, Mmari K, Gillespie DG. A qualitative study of patients’ use of expedited partner therapy. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2011;38(7):651–656. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31820cb206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. New York, NY: SAGE; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2015;64(RR-03):1–137. rr6403a1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T, de Kock A, Jones H, Altini L, Ferguson T, van de Wijgert J. A comparison of two methods of partner notification for sexually transmitted infections in South Africa: Patient-delivered partner medication and patient-based partner referral. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2007;18(5):338–340. doi: 10.1258/095646207780749781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]