Abstract

AMD is a complex multifactorial disease characterized in its early stages by lipoprotein accumulations in BrM, seen on fundoscopic exam as drusen, and in its late forms by neovascularization (“wet”) or geographic atrophy of the RPE cell layer (“dry”). Genetic studies have strongly supported a relationship between the alternative complement cascade, in particular the common H402 variant in Complement Factor H (CFH) and development of AMD. However, the functional significance of the CFH Y402H polymorphism remains elusive. In this article, we critically review the literature surrounding the functional significance of this polymorphism. Furthermore, based on our group’s studies we propose a model in which CFH H402 affects CFH binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans leading to accelerated lipoprotein accumulation in BrM and drusen progression. We also review the literature on the role of other complement components in AMD pathobiologies, including C3a, C5a and membrane attack complex (MAC) and on transgenic mouse models developed to interrogate in vivo the effects of the CFH H402 polymorphism.

1. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a complex, progressive, chorioretinal degenerative disease that affects the central region of the retina known as the macula (Fig. 1), the area responsible for the majority of high acuity, photopic vision (vision under well-lit conditions) (Jager et al., 2008). Three major factors contribute to AMD: advanced age, environmental factors (particularly smoking) (Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research, 2013; Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research, 2001; Christen et al., 1996; SanGiovanni et al., 2007; Seddon et al., 1994; Seddon et al., 2001; Seddon et al., 1996; Vingerling et al., 1996) and genetic risk factors, which will be described in detail below.

Figure 1.

Posterior eye ocular anatomy. (A) Cross-section schematic of a human eye showing major anatomical structures. (Image courtesy of Dr. Mikael Klingeborn) (B) Histological cross-section of retina and choroid in the perifoveal region of the macula. INL, inner nuclear layer; OPL outer plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; IS, inner segments; OS, outer segments; RPE, retinal pigmented epithelium; BrM, Bruch’s membrane; CC, choriocapillaris (image courtesy of Christine A. Curcio, PhD; http://projectmacula). IS and OS are artifactually separated.

AMD is broadly classified into three categories based on fundoscopic appearance of the macula: early, intermediate and late stage. The pathognomonic lesions of early and intermediate AMD are lipid- and protein-rich deposits known as drusen (Fig. 2). The word drusen (singular, “druse”), is derived from the German word for geodes. Drusen are typically detected on fundoscopic clinical exam, but are now visible by a variety of imaging modalities including optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Fig. 2). The deposition of a few small (diameter less than 63 microns) drusen is normal in aged eyes and is generally not vision impairing. The presence of intermediate (diameter between 63 and 125 microns) or large (diameter greater than 125 microns) drusen in the macula typically leads to vision impairment and is indicative of early or intermediate AMD (Li et al., 2001; Stangos et al., 1995). The diagnosis of early and intermediate AMD places a patient at high risk of progressing to later stages of the disease (Ferris et al., 2013). Late-stage AMD is categorized as either ‘dry’ (Fig. 2) [geographic atrophy, with photoreceptor loss and extensive retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) atrophy, also referred to as ‘atrophic’] or ‘wet’ (Fig. 2) [neovascular or exudative)], however, in many patients both ‘dry’ and ‘wet’ forms are evident (Ferris et al., 2013). The initial visual deficit in patients with aging and early AMD are in rod-mediated vision, especially rod-mediated dark adaptation and low luminance visual acuity (Owsley et al., 2016a; Owsley et al., 2001; Owsley et al., 2016b). Whereas, late-stage AMD is characterized by central scotoma and loss of central vision.

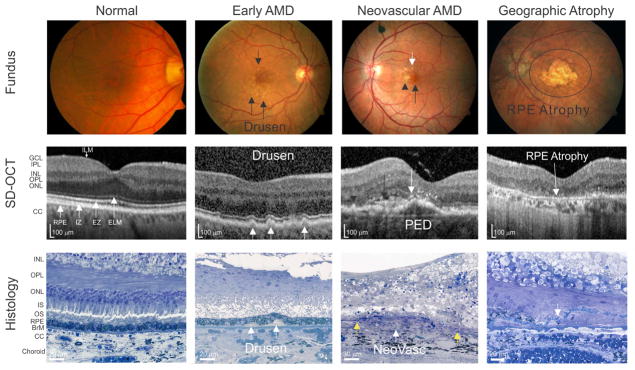

Figure 2.

Clinical and histological depictions of AMD. Fundus photographs (Fundus), Spectral Domain-Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT) images and chorioretinal histological sections (Histology) showing the normal eye and the characteristic lesions of early AMD, neovascular AMD, and geographic atrophy. Color fundus photographs, SD-OCT and histological images are not obtained from the same eyes. Normal: The corresponding SD-OCT of a normal color fundus demonstrating normal retinal structures and layers and intact four hyperreflective lines in outer retina (white arrows: RPE, retinal pigmented epithelium; IZ, interdigitation zone; EZ, ellipsoid zone; ELM, external limiting membrane). No sub-RPE or subretinal drusenoid deposits are noted in either the SD-OCT or the histology image. The break between the IS and OS in histology is a fixation artifact. Early AMD: Images showing small drusen on the color fundus photo (black arrows), SD-OCT (white arrows) and soft drusen on histopathology (white arrows). Neovascular AMD: Color fundus photograph depicts drusen (white arrow), pigmentary changes (black arrow head) and a foveal subretinal hemorrhage (black arrow); SD-OCT demonstrates a thin layer of subretinal fluid (black arrow), subretinal hyperreflective material (black arrowhead), and a large pigment epithelial detachment (PED) with overlaying hyper-reflective foci (white arrow); histology illustrates a neovascular complex (NeoVasc) between the two free ends of breached Bruch’s membrane (yellow arrows). Geographic atrophy: Color fundus image and SD-OCT depicts a well-demarcated area of fovea-involving RPE atrophy, while histology shows absence of the RPE and a blue-stained line of persistent basal laminar deposits (white arrow). GCL, ganglion cell layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; OPL outer plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; ELM, external limiting membrane; EZ, ellipsoid zone; IZ, interdigitation zone; CC, choriocapillaris; IS, inner segments; OS, outer segments; RPE, retinal pigmented epithelium; BrM, Bruch’s membrane. (Fundus and OCT images courtesy of Drs. Eleonora Lad and Katayoon Baradaran Ebrahimi and histological images courtesy of Dr. Christine A. Curcio)

Despite the fact that AMD is the leading cause of irreversible vision loss in the elderly in industrialized nations (Klein et al., 2002) and is expected to affect 196 million people worldwide by 2020 (Wong et al., 2014), limited therapeutic options are currently available for those suffering from the disease. For example, the progression of early and intermediate stage to late-stage AMD pathology can be delayed through dietary supplementation with the AREDS/AREDS2 anti-oxidant and mineral-based formulations (Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research, 2013; Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research, 2001). The AREDS2 formulation contains vitamin C, vitamin E, zinc oxide, cupric oxide, lutein and zeaxanthin (Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research, 2013). The major pharmacologic advancement in the treatment of late exudative AMD has been the utilization of intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapies (Heier et al., 2012; Rosenfeld, 2011; Rosenfeld et al., 2006). There are currently no therapies that stop or reverse dry (early or late) AMD.

A limited understanding of the pathogenesis of the disease has hampered the development of therapies for AMD. Genetic studies have provided researchers with valuable clues into the mechanisms underpinning AMD (Black and Clark, 2016). In particular, in 2005 four separate studies identified single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) variants within the complement factor H gene (CFH) on chromosome 1 that are associated with significantly increased risk for AMD (Edwards et al., 2005; Hageman et al., 2005; Haines et al., 2005; Klein et al., 2005). CFH encodes complement factor H (CFH) a regulator of the complement pathway, which is an arm of the innate immune system. Identification of specific variants in CFH as major genetic risk factors for AMD was a watershed moment in the understanding of the disease and supported previous studies implicating the complement cascade and chronic inflammation in AMD pathogenesis (Anderson et al., 2002; Anderson et al., 2010; Hageman et al., 2001; Johnson et al., 2001). Subsequently, genetic risk associations were found in other complement genes (Fagerness et al., 2008; Gold et al., 2006b; Maller et al., 2007; Yates et al., 2007) and ushered in an era of intense study of the complement system and its components as therapeutic targets. In this review, we will discuss the literature surrounding the genetic influence of CFH on AMD and the current understanding of how CFH regulates the early events in AMD pathogenesis. We also report on the role of other complement components on AMD pathobiologies including C3a, C5a and MAC. Finally, we will discuss current transgenic mouse models developed to interrogate the in vivo role of CFH in AMD pathogenesis.

2. Drusen

In depth understanding of the early pathological hallmarks of AMD has been essential to our understanding of the pathobiology of the disease. It has long been recognized that drusen are a hallmark lesion of early and intermediate AMD; the size, number and extent of confluency of drusen influence the risk of progression to late AMD (Bird et al., 1995; Pauleikhoff et al., 1990; Sarks et al., 1988, 1994; Sarks et al., 2007). Drusen, which are visible as small yellowish deposits under the retina on fundus examination (Fig. 3), were first identified in 1855 by the Dutch ophthalmologist, Franciscus Donders (Donders, 1855). Depending on the type and extent of examination and classification, up to 80% of patients over 60 years of age have some evidence of macular drusen (Augood et al., 2006; Klein et al., 1993; Leske et al., 1994; Varma et al., 2004). Thus, drusen are a common but not disease-specific lesion for AMD. They also occur in a variety of other diseases affecting the posterior eye (Francis, 2006; LeBedis and Sakai, 2008; Shenoy et al., 2010). While, the presence of macular drusen is considered a strong risk factor for the development of both forms of late AMD, atrophic and exudative, the specific contributions of drusen to AMD progression are not known. Therefore, clarification of the origin of drusen, as well as their implications in retinal health, is essential to our understanding of disease pathogenesis and the development of therapeutics for AMD.

Figure 3.

Association between funduscopically detected drusen and drusen imaged by SD-OCT and post-mortem histological staining. (A) Fundoscopic image of a patient with early AMD with significant macular drusen (yellow lesions, a few indicated by white arrows). (B) Image showing drusen (white arrows) as depicted by SD-OCT. (C) Histologic image of RPE/choroid interface and a single small druse (black arrow) subjacent to the RPE. Labels as in Figure 1. (Fundus and OCT images courtesy of Drs. Eleonora Lad and Katayoon Baradaran Ebrahimi and histological image courtesy of Dr. Christine A. Curcio)

2.1 Drusen localization

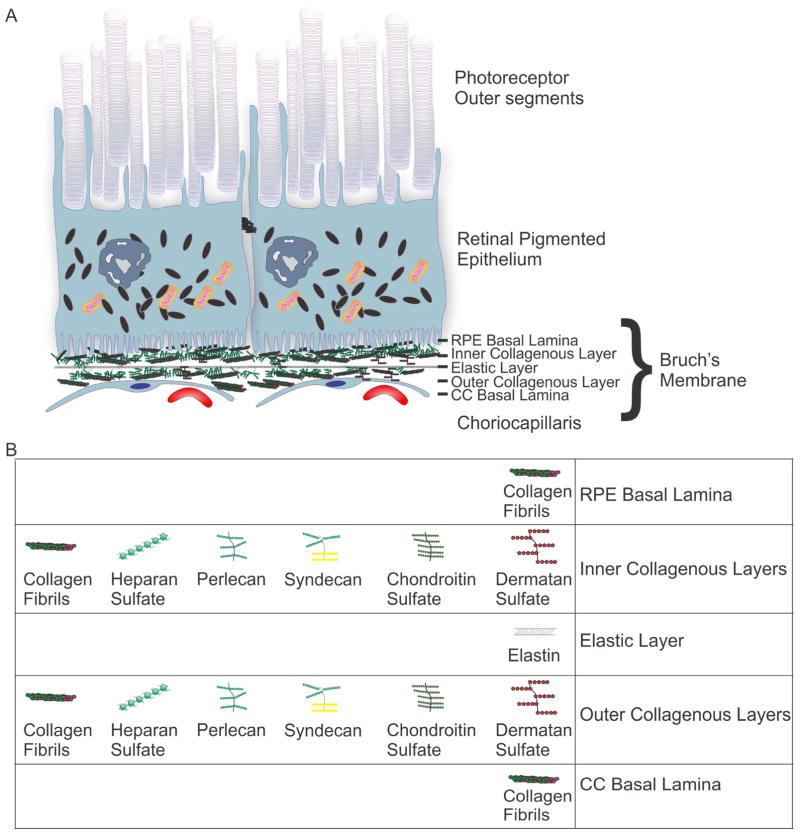

Early clinicopathological studies by S.H. Sarks described a linear deposit at the base of the RPE cells in association with inner surface of Bruch’s membrane (BrM) (Sarks, 1976). BrM is an organized pentalaminar extracellular matrix situated between the RPE and the capillary bed of the choroid known as the choriocapillaris (Hogan et al., 1971) (Fig. 4). BrM is not a true membrane; rather it is a thin (2–4μm thick), acellular matrix that includes the basal laminae of both the RPE and choroidal endothelial cells on its inner and outer aspects respectively (Fig. 4) (Curcio, 2013; Guymer et al., 1999). The five layers of BrM from the basal RPE side to the choroid are: RPE basal lamina, inner collagenous layer, elastic layer, outer collagenous layer and choriocapillaris basal lamina (Fig. 4). The structure of BrM is similar to vascular intima, with a subendothelial extracellular matrix and an elastic layer that is analogous to the internal elastic lamina of vessels (Curcio, 2013; Guymer et al., 1999). BrM differs from other vessel walls in that its abluminal surface abuts the basal lamina of an adjacent epithelium, which is also a characteristic of the renal glomerulus. This morphological similarity between BrM and the glomerulus, particularly the overlap between Type IV alpha3 and 4 collagens, (Butkowski et al., 1989; Chen et al., 2003; Harvey et al., 1998), as well as the fact that the luminal surfaces of each face a fenestrated vascular endothelium and basal lamina helps explain the overlap of some renal and retinal diseases, particularly AMD and Dense Deposit Disease (Curcio, 2013; Guymer et al., 1999; Mullins et al., 2001; Mullins et al., 2000). The inner collagenous layer is composed of a complex three-dimensional arrangement of collagen fibrils and proteoglycans with attached chains of all classes of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) (e.g. heparan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, dermatan sulfate and keratin sulfate) (Fig. 4B). Drusen form between the RPE basal lamina and the inner collagenous layer of BrM (Sarks, 1976). The composition, thickness and structural properties of BrM vary with age (Fisher, 1987; Lommatzsch et al., 2008; Okubo et al., 1999). In particular, collagen type IV content and collagen cross-linking increases with age, while collagen solubility decreases and advanced glycation end-product modifications accumulate (Guymer et al., 1999; Hamlin and Kohn, 1971; Handa et al., 1999; Ishibashi et al., 1998; Vater et al., 1979). In addition, lipid deposition increases with age (Curcio et al., 2011; Holz et al., 1994; Pauleikhoff et al., 1990) (discussed in more detail below). These age-related structural changes contribute to the increased hydraulic resistance seen in aged BrM (Ethier et al., 2004).

Figure 4.

Bruch’s membrane (BrM) layers and extracellular matrix composition. (A) Schematic of photoreceptor outer segments, RPE, BrM, and choriocapillaris (CC). BrM layers: basal lamina of the RPE, inner collagenous layer, elastic layer, outer collagenous layer and basal lamina of the choriocapillaris endothelial cells. (B) Extracellular matrix composition of BrM layers. The inner collagenous layer is composed of complex three-dimensional arrangement of GAGs including: collagen fibrils, heparan sulfate proteoglycans, perlecan, syndecan, chondroitin sulfate and dermatan sulfate.

2.2 Drusen composition

Histochemical and biochemical analyses of drusen have provided great insight into their origin and to their contributions to AMD, however, it should be noted that the majority of drusen composition studies were not performed on the “soft” macular drusen typically associated with late-stage AMD. Drusen are lipid-rich, with lipid-containing particles occupying 37–44% of drusen volume and a typical druse contains approximately 112 ng lipid compared to 42 ng of protein (Wang et al., 2010).

2.2.1 Proteins in drusen

Much of our initial understanding of the composition of drusen and the proteins that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AMD come from seminal studies using immunohistochemical and biochemical analyses of drusen in human donor eyes. Early immunohistochemical analyses showed that a large number of complement components, including CFH (Hageman et al., 2005; Johnson et al., 2006), Factor B (Gold et al., 2006a), C3 (Johnson et al., 2001; Mullins et al., 2000), C5 (Johnson et al., 2001)), complement activation products (including C5b-9 (Hageman et al., 2001; Johnson et al., 2001; Mullins et al., 2000) and activators of the complement cascade (including amyloid beta) (Dentchev et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2002; Loffler et al., 1995), C-reactive protein (CRP) (Johnson et al., 2006) and immunoglobulin (Johnson et al., 2000; Mullins et al., 2000), are molecular constituents of drusen. The presence of complement components (including CFH, C3, C5, C6, C7, C8, C9) in drusen was also shown by proteomic analysis (Crabb et al., 2002). In addition, other complement-regulatory molecules, including vitronectin and clusterin, are also prevalent in drusen (Crabb et al., 2002; Hageman et al., 1999; Hawse et al., 2003; Jenne et al., 1991; Milis et al., 1993). These studies contributed to a comprehensive profiling of the molecular composition of drusen leading to a model of AMD pathogenesis based on the effects of chronic inflammation proposed by Hageman et al. (Hageman et al., 2001). This “inflammation” model of AMD implicates local complement activation as a major event in the pathogenesis of AMD (previously reviewed by (Anderson et al., 2002; Anderson et al., 2010; Hageman et al., 2001). Additional immunohistochemical and biochemical analyses showed significant amounts of apolipoproteins (including ApoE) (Crabb et al., 2002; Klaver et al., 1998; Mullins et al., 2000), as well as additional amyloids, plasma constituents, and cellular components (Mullins et al., 2000). Furthermore, in vitro analysis of sub-RPE deposits from cultured fetal RPE cells, showed RPE cell production of basally secreted ApoE-containing particles that trigger complement activation (Johnson et al., 2011).

2.2.2 Lipid in drusen

The lipid-containing particles in drusen resemble those that accumulate in BrM and basal linear deposits, which are hypothesized to be the precursors to drusen (Curcio et al., 2011). BrM lipid accumulation with age and basal linear deposits appear in the same histological plane as drusen and contain similar vesicular histological hallmarks (Curcio et al., 2011; Pauleikhoff et al., 1990).

Wolter and Falls used Oil Red O to stain for non-polar lipids and demonstrated the rich lipid content of drusen (Wolter and Falls, 1962). Further histochemical analysis of BrM and drusen identified the presence of phospholipids and unesterified and esterified cholesterol; these accumulate with age in both BrM and drusen (Curcio et al., 2001; Holz et al., 1994; Pauleikhoff et al., 1990). There is considerable variability among individuals in the lipid composition of their drusen (Pauleikhoff et al., 1990). While some drusen contain predominantly neutral lipids, others are dominated by phospholipids, however, all drusen contain esterified and unesterified cholesterol (Curcio et al., 2005; Holz et al., 1994; Li et al., 2007; Pauleikhoff et al., 1990; Pauleikhoff et al., 1994).

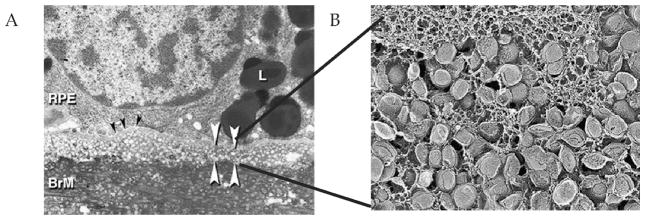

In the late 1990s and early 2000s genomic analysis of AMD patients revealed an association between lipid transport pathways, including apolipoproteins, and modification of risk for the development of AMD (Chen et al., 2010; Klaver et al., 1998; Neale et al., 2010; Souied et al., 1998). Correlating these findings with the lipid accumulation studies in BrM, Curcio et al. investigated the role of RPE-derived lipoproteins in age-related lipid accumulation, which led to their “Oil Spill” hypothesis of lipid accumulation in BrM (Curcio et al., 2011). Utilizing quick-freeze deep-etch, a freeze-fracture method to preserve lipids for electron microscopy, the authors observed round vesicles 60–80 nm in diameter with a core-shell structure that the authors later termed lipoprotein-like particles (Fig. 5). Subsequent analysis showed that these lipoproteins accumulate with age between the inner collagenous layer and elastic layer of BrM (Fig. 4), forming what they termed the “lipid wall” (Fig. 5) (Huang et al., 2007; Li et al., 2007). Isolation of lipoprotein-like particles from BrM extracts revealed two fractions one with 60–80 nm vesicles containing predominantly cholesterol esters, and a second containing a more heterogeneous population of vesicles predominantly comprised of unesterified cholesterol, lipids, and phospholipids (Li et al., 2005; Li et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2009b). Furthermore, cultured RPE-J cells, an immortalized rat RPE cell line, have been shown to secrete 60–80 nm ApoB-containing lipoprotein-like particles consistent with the lipoprotein-like particles seen in BrM, and in contrast to circulating high density lipoprotein (HDL) and low density (LDL) particles which range from 8–13 nm to 15–25 nm, respectively (Wang et al., 2009b). In addition, a recent study showed that long-term porcine RPE cultures form basal deposits with histochemically detectable lipid (Pilgrim et al., 2017). The experiments by Curcio et al. demonstrate that a portion of the lipid accumulation in BrM is made up of lipoprotein-like particles derived from the RPE. However, the origin of the RPE-derived lipids remains to be determined. There are two major cholesterol and fat sources for RPE cells: (1) daily phagocytosis of membrane-rich photoreceptor outer segments (OS); and (2) uptake of peripheral LDL particles from systemic circulation for retinal lipid supply (Peters et al., 2006; Rungger-Brandle et al., 1987; Tserentsoodol et al., 2006a; Tserentsoodol et al., 2006b). Based on the high content of linoleate (a lipid abundant in LDL), and low concentration of cholesteryl docosahexaenoate or cholesteryl stearate (abundant in OS), Curcio et al. concluded that the source of esterified cholesterol in BrM is from circulating LDL particles in blood processed by the RPE cells and deposited on the basal side of the RPE in BrM. (Bretillon et al., 2008; Li et al., 2005).

Figure 5.

Accumulation of BrM-associated lipoprotein-like particles leads to formation of lipid wall. (A) Transmission electron micrograph showing lipoprotein-like particles that accumulate between the RPE basal lamina (black arrowheads) and BrM inner collagenous layer as vesicles with lucent interiors forming the lipid wall (white arrowheads). (B) Quick freeze deep etch electron microscopic image of the lipoprotein-like particles in BrM. These pathological findings were posited to represent the RPE-derived “lipid-wall” lipoprotein layer that accumulates in BrM with age and may be a precursor to drusen formation. [Adapted from (Curcio et al., 2011)] (Images courtesy of Christine Curcio)

2.3 Basal laminar deposits and Sub-retinal drusenoid deposits (SDD)

In addition to drusen, other histologically evident deposits have been associated with AMD. Including the sub-RPE basal laminar deposits which, when found under the macula, are a defining feature of AMD and causally associated with macular risk of AMD (Rudolf et al., 2008a; Sarks, 1976). Notably, these deposits are the predominant lesion present in aged murine models of AMD (Toomey et al., 2015).

More recently, researchers have appreciated the presence of another extracellular deposits related to AMD located between the RPE and photoreceptors termed subretinal drusenoid deposits (SDD) (Spaide, 2013). SDD appear to have similar protein composition, including complement components (Rudolf et al., 2008b), to that of drusen. Thus, we suspect that the pathologic processes contributing to the biogenesis of SDD are similar to those contributing to the development of sub-RPE drusen. Due to their relatively recent identification and description, SDDs are not considered in detail here.

Together, histochemical and biochemical analyses of drusen and BrM proteins, lipids and lipoproteins have provided a framework that shaped our understanding of AMD pathobiology to include lipoprotein production by RPE cells and complement activation.

3. Complement system

In the early to late 2000s, two distinct lines of evidence showed a link between the complement cascade and AMD pathogenesis. First, immunohistological and proteomic analysis of post-mortem tissue from patients with AMD revealed the presence of complement proteins and activation products in drusen (Anderson et al., 2002; Anderson et al., 2010; Crabb et al., 2002; Hageman et al., 2005; Hageman et al., 2001; Mullins et al., 2000). Second, population-based genetic analyses showed several variants in complement proteins to be associated increased risk for AMD (Edwards et al., 2005; Hageman et al., 2005; Haines et al., 2005; Klein et al., 2005). In this review, we will discuss these findings in greater detail. However, first we will explore the composition and function of the complement cascade.

3.1 Complement cascade

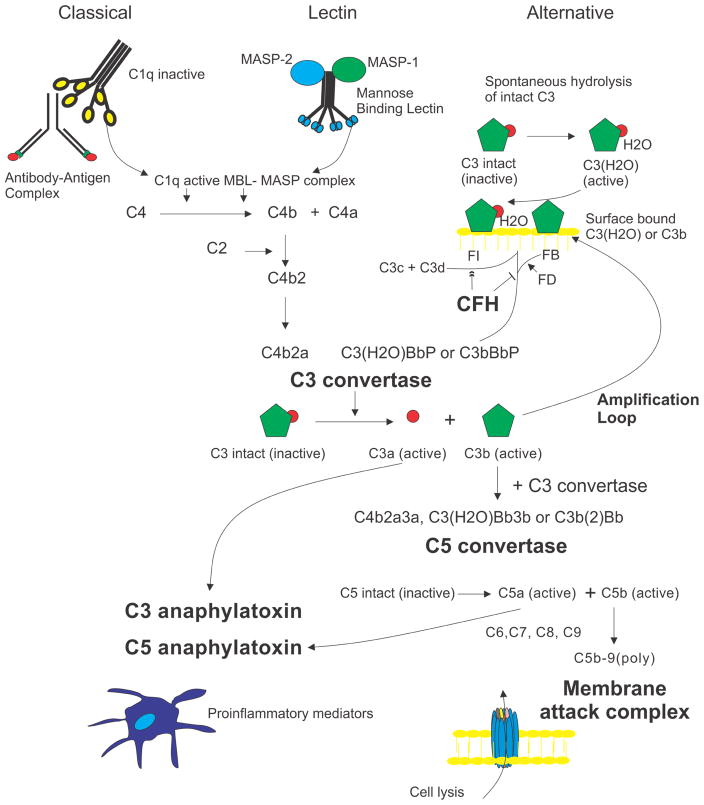

The complement system is amongst the oldest evolutionary components of the immune system. It was discovered in 1896 as a heat-labile fraction of serum that led to opsonization of bacteria. Biochemical characterization showed that the complement system is composed of over 30 proteins that function to mediate removal of apoptotic cells and eliminate pathogens (Sarma and Ward, 2011). Three separate pathways (i.e. classical, alternative and lectin pathways) converge to convert C3 to C3b forming the C3 convertase, an enzyme capable of initiating a cascade that results in the formation of the immunostimulatory breakdown products, C3a and C5a, and the membrane attack complex (MAC, C5b-9), a cell membrane pore that can cause cell lysis (Sarma and Ward, 2011) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Overview of the complement system. Stimulated by antigen:antibody complexes, bacterial cell surfaces, and spontaneous hydrolysis, respectively, the classical, lectin, and alternative pathways converge to convert C3 to C3 convertase, an enzyme capable of initiating a cascade that results in 3 major effector functions: the formation of two anaphylatoxins, C3a and C5a, and generation of a cell membrane-spanning pore known as the membrane attack complex (MAC) that leads to cell lysis. There are two known inhibitory roles of the soluble regulator, CFH, within the complement cascade: 1) blocking the binding of Factor B to C3b and C3(H2O) and (2) acting as a co-factor to serum protease Factor I which functions to inactive C3b by cleaving it to generate the C3c and C3d inactivation products. MBL: Mannose binding lectin; MASPs: MBL-associated serine proteases; FB: Factor B; FD: Factor D; FI: Factor I.

3.2 Alternative pathway of complement

The classical and lectin complement pathways are initiated by the recognition of specific protein or carbohydrate targets. The immunoglobulins, IgM and IgG, and CRP activate the classical pathway. The lectin pathway is initiated by the interaction of mannose-binding lectin with repeating carbohydrate moieties found on bacterial surfaces. In contrast, the alternative pathway is initiated by the spontaneous hydrolysis of a thioester bond in C3 to form C3(H2O); hourly 0.2 to 0.4% of total C3 changes its conformation from C3 to C3(H20) (Pangburn and Muller-Eberhard, 1983) (Fig. 6). C3(H20) is capable of binding to Factor B (FB), resulting in a conformational change in FB. This conformational change allows Factor D, a constitutively active serum protease, to cleave FB to Factor Bb. Factor Bb is retained within the C3(H20)Bb complex where it acts as a serum protease for C3, cleaving it to C3b, which can in turn associate with FB to generate more C3 convertase (C3bBb). This auto-activation process is known as “tickover” (Sarma and Ward, 2011). Blurring the trichotomy between these pathways, however, is the role of the alternative pathway as an “amplification loop” of the complement cascade. In the “amplification loop”, C3b, generated from either the classical or lectin pathway, binds to FB to generate additional C3 convertase (Fig. 6). This “amplification loop” has been shown to be responsible for more than 80% of the C5a and membrane attack complex formation in both the classical and lectin pathways (Harboe et al., 2009; Harboe et al., 2004). Thus, the alternative pathway is responsible for the fluid–phase, spontaneous activation and amplification of C3 cleavage (Fig. 6).

3.3 Complement factor H (CFH)

Continuous control of the alternative pathway is necessary due to the spontaneous nature of the activation, its amplifying properties and its potential to provoke lysis in normal host tissues. The major negative fluid-phase regulator of the alternative complement cascade is Factor H (CFH). CFH is an abundant (218–654 μg/ml in serum) 155 kDa protein made up of twenty domains known as short consensus repeats (SCRs) or complement control protein (CCP) modules (Ansari et al., 2013; Schmidt et al., 2010). CFH SCRs 1–4 regulate the alternative pathway C3 convertase via two mechanisms: 1) CFH accelerates the decay of the C3 convertase and blocks its assembly by preventing the binding of FB to C3b and C3(H20) and 2) CFH promotes the irreversible inactivation of C3b to iC3b by the C3b serum protease, Factor I (FI); acting as a cofactor for FI-mediated cleavage of C3b. CFH functions not only in the fluid phase but also in the extracellular matrix and at host cell surfaces via its binding domains for polyanions, including heparan sulfate in SCRs 6–7 and 20 (Blaum et al., 2015; Clark et al., 2006). CFH thus regulates the spontaneous activation and amplification of C3 cleavage and assists in the degradation of active C3 cleavage products on host cells (Fig. 6).

4. Genetic discovery of the risk association of CFH with AMD

4.1 Genetics in AMD

Although Gass anticipated a genetic susceptibility in patients with AMD in 1972 (Gass, 1972), twin and population-based familial aggregation studies provided some of the earliest evidence of genetic susceptibility in AMD (Hammond et al., 2002; Klein et al., 2001; Klein et al., 1994; Meyers et al., 1995; Seddon et al., 1997). In fact, twin studies demonstrated that genetic factors account for 67% and 71% of the variation in disease risk for intermediate and advanced AMD, respectively (Seddon et al., 2005). Family based linkage analysis studies by R. J. Klein and colleagues were the first to report linkage to chromosome 1q25–31 in a large pedigree with an apparent autosomal dominant inheritance for “dry” AMD (Klein et al., 1998), which was then supported by a number of other linkage studies (Abecasis et al., 2004; Iyengar et al., 2004; Majewski et al., 2003; Seddon et al., 2003; Weeks et al., 2004). In contrast, candidate gene analysis, focusing on rare inherited macular dystrophies with phenotypic similarities to AMD, was limited in their ability to identify genes with significant risk association with AMD. Thus, although AMD pathobiology is dependent on aging, genetic heritability is a significant risk factor for the disease. In fact, it has long been appreciated that understanding the contributing genetic factors will provide insights into the relevant sequence of events in the aging chorioretina that lead to AMD.

4.2 CFH risk alleles

Significant advances in sequencing technologies and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have provided substantial additional insight into the genetic architecture of AMD phenotypes. The first successful GWAS, in 2005, lead to the identification of an intronic variant in the CFH gene that is strongly associated with AMD (Klein et al., 2005). Further focused resequencing within the original cohort, in search of a functional variant within the CFH gene, led to identification of a T to C change in exon 9 that was the most strongly associated non-synonymous SNP in the analysis (Klein et al., 2005). Three other groups concomitantly revealed that this common haplotype in the CFH gene predisposes individuals to AMD (Edwards et al., 2005; Hageman et al., 2005; Haines et al., 2005). This risk haplotype was highly associated with a non-synonymous SNP resulting in a tyrosine (Y) to histidine (H) exchange at position 402 of the CFH protein (the “Y402H polymorphism”). This risk association has been supported in many subsequent studies and the presence of at least one CFH risk allele is estimated to account for a population attributable risk fraction for early and late AMD of 10% and 53%, respectively (Klein et al., 2013). Several studies specifically related the CFH risk allele to early AMD, drusen and disease progression (Delcourt et al., 2011; Dietzel et al., 2014; Gangnon et al., 2012; Holliday et al., 2013; Magnusson et al., 2006). The Y402H polymorphism is located in SCR 7, a region that is known to mediate CFH binding to polyanions such as heparin, glycosaminoglycans, and CRP (Fearon, 1978; Mold et al., 1984), but is not involved in regulation of complement activation (Rodriguez de Cordoba et al., 2004; Zipfel and Skerka, 2009). The functional implications of the Y402H polymorphism will be explored in detail below. Further analysis of the CFH gene has revealed five distinct haplotypes, two of which significantly alter AMD risk: the H1 common risk haplotype (containing the CFH Y402H polymorphism) and the H2 protective haplotype (containing the protective CFH I62V polymorphism) (Hageman et al., 2005).

4.3 Rare mutations in CFH

Due to the strong association between the H1 common risk haplotype of CFH and AMD, there was significant interest in the analysis of rare variants that alter the peptide sequences, truncate proteins or affect RNA splicing to corroborate a causal mechanism (Fritsche et al., 2016; Raychaudhuri, 2011; Raychaudhuri et al., 2011). In 2011, Raychaudhuri et al. identified a rare, but highly penetrant, non-synonymous variant in CFH at Arg1210 where Arginine is substituted by Cysteine (Raychaudhuri et al., 2011). Interestingly, this rare variant occurs in SCRs 19–20, a second region of CFH involved in binding to GAGs and which has been associated with extensive macular drusen accumulation and advanced disease (Ferrara and Seddon, 2015). The studies further suggest a role of CFH-HS interaction in drusen formation. Using whole exome sequencing in families with high AMD disease burden and no known common genetic risk alleles, Yu et al. identified two rare variants in CFH, R53C and D90G, which functionally appear to have decreased decay accelerating activity and cofactor mediated inactivation ability, respectively (Yu et al., 2014). More recently, studies looking for other rare mutations in complement component genes showed enrichment of rare variants in CFH in AMD patients in both SCRs 1–4 and SCRs 19–20 (Triebwasser et al., 2015).

4.4 Common polymorphisms in other alternative pathway components, C3, FB, and FI

Evidence for the role of the alternative pathway of complement activation in AMD was further supported by the subsequent identification of common polymorphisms in other components involved in the alternative pathway of the complement cascade. Variations in C3 (R102G), FB (R32Q), both common and rare variants in FI and new variants in CFH have also been linked to AMD risk (Fagerness et al., 2009; Gold et al., 2006a; Hageman et al., 2005; Kavanagh et al., 2015; Maller et al., 2006; Maller et al., 2007; Seddon et al., 2013; Spencer et al., 2008; Yates et al., 2007). In studies interrogating the functional impact of combinations of these variants, Heurich et al. demonstrated that the combination of the C3 (102G), FB (32R) and CFH (62V) AMD risk-associated variants correlates with six-fold higher serum hemolytic activity (indicative of increased activity of the complement cascade) compared with the combination of the protective variants C3 (102R), FB (32Q) and CFH (62I) (Heurich et al., 2011). This observation provides strong proof of principle that combinations of polymorphic variants of the complement activators and regulators or “complotypes” within individuals can influence complement dysregulation (Heurich et al., 2011).

4.5 Non-coding variants in CFH

Although the H402 substitution explains a large fraction of the genetic risk attributed to AMD, definitive proof for the involvement of CFH H402 is lacking due to the high linkage disequilibrium in CFH (Ennis et al., 2007; Fritsche et al., 2013). The linkage disequilibrium in CFH results in 5 common (occurring in at least 2% of genome subject chromosomes) haplotypes. The most common haplotype (H1) shows the highest association for AMD [2.46 odds ratio (OR), confidence interval (CI) 1.95–3.11] and is 95% associated with the CFH H402 amino acid substitution (Hageman et al., 2005). Ansari et al. were able to show that non-coding SNPs are associated with alterations in CFH plasma concentrations (Ansari et al., 2013). However, the cumulative effect of non-coding SNPs on CFH concentration is relatively small; AMD patients exhibit only 3.7% lower plasma CFH levels (428 μg/mL versus 412 μg/mL). Considering human plasma CFH concentrations are normally distributed within a 3-fold range (218–654 μg/mL) with a standard deviation of 62 μg/mL (15%), this statistically significant observation would appear to be biologically insignificant (Ansari et al., 2013).

4.6 CFH genetics and kidney disease

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) type II (MPGN II) is a rare kidney disease where mutations in CFH lead to chronic uncontrolled alternative pathway complement activation and glomerulonephritis in a subset of MPGNII patients (Neary et al., 2002). MPGN II is characterized pathologically by the accumulation of C3 and electron-dense deposits in the glomerular basement membrane, a structure similar to BrM where drusen form in AMD (Curcio, 2013). Interestingly, prior to discovery of a genetic link between CFH and AMD, it was well established that patients with MPGN II develop early ocular drusen (Colville et al., 2003; Mullins et al., 2001; Neary et al., 2002; O’Brien et al., 1993). This connection was supported by data showing that 70% of patients with MPGN II harbored the CFH H1 haplotype (Hageman et al., 2005). The association of CFH risk variants and ocular drusen in MPGN II provides further evidence for a role of CFH in the biogenesis of drusen.

Another kidney disease, atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS), also has been associated with mutations and polymorphisms in the CFH gene (Buddles et al., 2000; Caprioli et al., 2003; Ying et al., 1999; Zipfel, 2001; Zipfel and Skerka, 2009; Zipfel et al., 2001). aHUS is characterized pathologically by renal endothelial injury, systemic small vessel thrombosis and hemolytic anemia (Zipfel, 2001). The renal endothelial and systemic thrombotic pathobiology seen in aHUS is pathologically distinct from MPGN II and there have been no studies linking aHUS and drusen formation. Genetically, aHUS is associated with mutations in C-terminal SCRs (16–20) of CFH (Rodriguez de Cordoba et al., 2004) and is not associated with the AMD and MPGN II common risk haplotype (H1) (Pickering et al., 2007). In addition, although the CFH R1210C mutation is associated with aHUS and AMD, AMD and aHUS appear to be mutually exclusive pathologies (Raychaudhuri et al., 2011; Recalde et al., 2016). Furthermore, Cfh gene deletion in mice results in renal pathology resembling MPGN II (Pickering et al., 2002), whereas, mice with deletion of SCRs 16–20 in CFH develop renal pathology resembling aHUS (Pickering et al., 2007). Thus, although MPGN II and AMD share pathologic and genetic similarities, mutations in the SCR 16–20 regions of CFH associate with the unique systemic pathology seen in aHUS (Pickering et al., 2007; Recalde et al., 2016). Recent studies have established that CFH interacts with the C-terminus of von Willebrand factor (VWF) thereby enhancing VWF’s cleavage by ADAMTS-13 (Feng et al., 2013; Nolasco et al., 2013). In fact, lower ADAMTS-13 activity has been found in patients with aHUS and may explain the clinical differences between MPGNII and aHUS (Remuzzi et al., 2002; Veyradier et al., 2003).

5. CFH variant functions

Since the identification of the risk association between the common CFH Y402H polymorphism and AMD, researchers have focused on identifying the mechanism by which the CFH H402 variant affects AMD pathobiology. Over the past decade several groups have published, sometimes conflicting, studies aimed at defining a CFH function that is altered in the CFH H402 variant and is relevant to AMD pathobiology. In the following sections, we will evaluate the available data.

5.1 Complement regulation

The canonical function of CFH protein is as a fluid phase inhibitor of the alternative pathway. It controls alternative pathway amplification by dissociating the enzymatic Bb domain from the C3 convertase and by catalyzing FI cleavage of C3b (Fearon, 1978). Structurally CFH is comprised of 20 tandem SCRs. The common polymorphisms of the H1 haplotype conferring risk for AMD occur in SCR7 while the complement-regulatory domains associated with the protein’s canonical functions are in SCRs1–4. Furthermore, functional assays comparing the co-factor activity of CFH H402 and Y402 in factor I mediated cleavage of C3b show no variant differences (Kelly et al., 2010). Although there are reports indicating that patients with the CFH H402 polymorphism have elevated C3d/C3 ratios (Smailhodzic et al., 2012) this has not been replicated by other studies (Ristau et al., 2014), and the majority of clinical studies have shown no relationship between the CFH H402 polymorphism and other proteins involved in complement activation (Hecker et al., 2010; Silva et al., 2012; Smailhodzic et al., 2012). Together these finding suggest that CFH H402 polymorphism does not directly alter the complement regulatory functions of the CFH protein.

5.2 Binding to C-reactive protein (CRP)

C-reactive protein (CRP) is an acute-phase reactant with multiple functions including the activation of the classical complement pathway and the upregulation of pro-inflammatory mediators by endothelial cells, neutrophils and macrophages (Black et al., 2004; Devaraj et al., 2004; Pasceri et al., 2000; Singh et al., 2006). CRP has been identified in drusen via immunohistochemistry (Johnson et al., 2006; Laine et al., 2007) and has been shown to be elevated in serum of AMD patients (Seddon et al., 2004); however, the precise function of CRP in the chorioretinal tissue and its effects on AMD progression are largely unknown. CRP levels were shown to be elevated in the choroid of CFH H402 patients compared to CFH Y402 (Johnson et al., 2006). Another study showed that the CFH H402 variant exhibited decreased binding to CRP and that binding occurred only to denatured CRP in the protomeric form, which was not thought to be of physiologic relevance (Hakobyan et al., 2008). This was revisited by Okemefuma et al., who showed that there was CRP binding at two different CFH sites (including SCR 7) under physiological conditions (Okemefuna et al., 2010). Other studies have shown that although CRP exists as a non-covalent pentamer composed of five identical subunits, it can dissociate into monomers under oxidative stress and upon interaction with bioactive lipids (Eisenhardt et al., 2009a; Eisenhardt et al., 2009b; Ji et al., 2007; Lauer et al., 2011; Thiele et al., 2014; Volanakis, 2001). Molins et al. showed that the monomeric form and not the pentameric form of CRP can bind to CFH at physiologically relevant concentrations and that the CFH H402 risk-variant binding was reduced compared to the CFH Y402 binding, which could increase inflammatory-mediated damage (Molins et al., 2016). In addition, Chirco et al. demonstrated that monomeric CRP is prevalent in the choriocapillaris and increased in patients with CFH H402 variant (Chirco et al., 2016), as originally shown by Johnson et al. (Johnson et al., 2006). Molins et al. propose that formation of monomeric CRP (either by spontaneous generation from the pentameric form or via activity of bioactive lipids on damaged cells under pathological conditions) leads to the activation of cytokines, a process that is attenuated by CFH, in a variant-dependent manner (Molins et al., 2016). However, future investigation into the pathophysiology surrounding monomeric CRP and its mechanistic relationship to the development of AMD in vivo is needed to clarify this relationship.

5.3 Interaction with heparan sulfate

The CFH molecule has two heparan sulfate (HS)-binding domains (SCRs 6–8 and SCRs 19–20) that facilitate binding to host cell surface GAGs, thereby protecting host tissue from complement damage (Schmidt et al., 2008). In a series of publications from 2006 to 2013, using both in vitro assays and ex vivo BrM-binding assays Clark et al. described CFH H402 as having decreased binding to BrM-associated HS compared to the CFH Y402 variant (Clark et al., 2006; Clark et al., 2010; Clark et al., 2013). These observations provided an explanation for how the H402 variant might increase AMD risk. Based on the fact that BrM is rich in HS, it was hypothesized that individuals with the CFH H402 variant have lowered levels of BrM-associated CFH due to its reduced affinity for HS. This likelihood was subsequently validated in post-mortem human BrM tissue by this same group of researchers (Keenan et al., 2014). Thus, lowered affinity for HS in the CFH H402 variant could lead to increased AMD risk by decreasing the total amount of complement-inhibiting CFH present in BrM. While very compelling, these studies relied on the use of recombinant fragments (SCRs 6–8) of the CFH protein instead of the full-length protein. We and others have had difficulty reproducing the observed decreased affinity of the CFH H402 variant for HS in experiments using the purified, full-length CFH protein (Kelly et al., 2010; Ormsby et al., 2008) (Fig. 7). We suspect that recombinant fragments may not fully represent the three-dimensional flexibility and/or post-translational modifications of the native protein; nor, do heparin plate-binding assays fully represent the complexity of HS proteoglycans present within human BrM. We have found that on BrM explants there is no difference between the binding of full-length CFH H402 and that of full-length CFH Y402 (Fig. 7). Thus, further studies of the effects of the CFH H402 variant on CFH binding to HS are warranted to resolve these discrepancies.

Figure 7.

CFH 402H variant does not show decreased binding to human BrM/choroid compared to the Y402 variant. Human BrM/choroid tissue punches from aged (73–79 years old), genotype-matched post-mortem donors were isolated, treated to remove adherent cells from BrM, and exposed to 1 μM full-length CFH Y402 (N=10) or CFH H402 (N=11) freshly isolated from homozygous blood bank donors as previously described (Kelly et al., 2010). Bound CFH was quantified by Western blot using CFH standard curves Equal binding was noted and type II error was calculated to establish statistical significance of the null hypothesis (β<0.05).

Crystal structure and mutation analyses of recombinant fragments of CFH suggest that the CFH H402 amino acid is involved in HS binding in a more complex manner than what was initially assumed (Prosser et al., 2007). Specifically, the authors suggest that the CFH H402 variant is involved in recognizing specific sulfation patterns, as supported experimentally by Clark et al. in 2013 (Clark et al., 2013; Prosser et al., 2007). A new paradigm was proposed in which specific sulfation patterns within the BrM extracellular matrix form “zip codes” whereby CFH is recruited (Keenan et al., 2014). Based on this paradigm the CFH H402 polymorphism alters the “zip code” recognition of CFH, which could result in lower levels of the H402 variant in BrM compared to the Y402 variant(Keenan et al., 2014). This paradigm, however, would be greatly strengthened by in vivo validation.

5.4 Binding of oxidative stress markers

Increased oxidative stress, particularly due to smoking, is associated with AMD pathogenesis (Beatty et al., 2000; Hollyfield et al., 2008; Seddon et al., 2006; Seddon et al., 1996). Using an unbiased proteomic approach to identify plasma proteins that interact with malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of lipid peroxidation associated with oxidative stress, Weismann et al. discovered that CFH is a major MDA-binding protein and established it as an innate defense protein against MDA (Weismann et al., 2011). The binding of CFH to MDA results in masking of the pro-inflammatory activities of MDA (Weismann et al., 2011). It was further documented that the CFH H402 variant binds MDA less efficiently than the Y402 variant, predicting that patients with H402 variant have an impaired ability to regulate oxidative stressors and implicating it as a possible mechanism for the increased risk for AMD associated with the H402 variant (Weismann et al., 2011).

CFH interaction with oxidized phospholipids was further supported in a study by Shaw et al. (Shaw et al., 2012), demonstrating that the CFH H402 variant bound with less affinity to oxidized phospholipids than the normal Y402 form (Shaw et al., 2012). The implication that CFH regulates the inflammatory responses caused by MDA and oxidized phospholipids is particularly intriguing since these findings provide a link between oxidation motifs, lipids and CFH H402 risk association in AMD. Studies of a mouse model expressing a chimeric CFH transgene with the human SCRs 6–8 sequences of the H402 or Y402 CFH variants (chCFHTg mice, (Aredo et al., 2015)) indicate that such interactions are present in vivo. This model shows that the H402 variant in CFH SCR6–8 leads to higher levels of MDA-adducts compared to normal age-matched C57BL/6 controls, as well as increased microglial/macrophage uptake of MDA (Aredo et al., 2015).

6. Mouse Models of Complement Dysregulation and AMD

With the relationship between complement activation and AMD established in human patients, mouse models have provided a conduit to dissect the molecular mechanisms linking exaggerated complement responses and AMD pathobiology. While none of the available models fully recapitulate human AMD pathogenesis, studies of these models have provided important insights into the role of complement in numerous AMD-associated disease processes.

6.1 Complement effects in the laser-induced CNV mouse model

Early studies delving into the effects of complement in murine models of AMD focused on wet AMD, which is traditionally modeled by laser-induced choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in mice (described by (Ishibashi et al., 1987) and recently revisited by (Poor et al., 2014)). Laser-induced CNV is a frequently used experimental technique that induces breaks in BrM, stimulates neovascularization from the choriocapillaris, and resembles CNV seen in exudative AMD (Lambert et al., 2013). The laser-induced CNV mouse model of exudative AMD produces relatively quick results within a few weeks, but it may not reflect the progressive nature of AMD development and most likely reflects a wound healing response (Grossniklaus et al., 2010). Despite this caveat, the laser-induced CNV mouse model has been used to establish a role for complement in CNV development and progression, specifically the alternative pathway (Bora et al., 2006; Rohrer et al., 2011; Schnabolk et al., 2015), complement anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a (Coughlin et al., 2016; Nozaki et al., 2006) and MAC (Bora et al., 2005). In fact, over activation of the alternative pathway contributes to CNV lesion size as supported by increased laser-induced CNV lesion size in mice treated with siRNAs targeting mouse Cfh (Lyzogubov et al., 2010) and in CFH deficient mice (Lundh von Leithner et al., 2009). Complement activation in laser-induced CNV was detected at lesion sites in the posterior eye using systemic injection of monoclonal C3d antibodies (Thurman et al., 2013). Studies by Rohrer et al. showed that mice lacking the alternative pathway (FB deficient) exhibited reduced levels of CNV following laser treatment compared to mice lacking the classical pathway (C1q deficient) or MBL pathway (MBL deficient) (Rohrer et al., 2009). In addition, the same group showed that forced expression of FB in the RPE promotes laser-induced CNV lesions (Schnabolk et al., 2015). Using a novel recombinant protein that targets CFH-mediated alternative pathway inhibition to areas of complement activation (CR2-fH) (Huang et al., 2008), Rohrer and colleagues showed that pharmacological inhibition of the alternative pathway reduces laser-induced CNV (Rohrer et al., 2012; Rohrer et al., 2009). Recent studies by Poor et al. (2014) cite a need for repetition of some of the published laser CNV studies due to inconsistent strain- and vendor-dependent differences (Poor et al., 2014). However, multiple studies have confirmed the role of the alternative pathway and C5a in the laser-induced CNV model in mice (Coughlin et al., 2016; Nozaki et al., 2006). Specific mechanisms of action remain to be elucidated.

6.2 Complement and oxidative stress injury models

Smoking is one of the strongest environmental risk factors for development of AMD (Klein et al., 1993; Myers et al., 2014). Considering this association, researchers have utilized smoke-induced ocular injury to model ocular damage seen in AMD (Fujihara et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009a). The alternative pathway also appears to play a role in smoke-induced ocular injury, as Factor B deficient mice have reduced visual function decline and less outer nuclear layer thinning compared to wild type mice treated with cigarette smoke (Woodell et al., 2013). In vivo studies in these alternative pathway deficient mice exposed to cigarette smoke, accompanied by studies of RPE cell cultures exposed to cigarette smoke extract, revealed a stress-mediated lipid accumulation in the ER and lipid secretion supporting a synergistic interaction of oxidative stress and the alternative pathway in AMD (Kunchithapautham et al., 2014). Cigarette smoke is thought to contribute to AMD pathobiology through the creation of free radicals (Church and Pryor, 1985) and direct activation of the complement cascade (Kew et al., 1985; Robbins et al., 1991) (recently reviewed in (Datta et al., 2017). The above results suggest that at least some of the retinal pathology resulting from smoking appears to be due to complement activation. In fact, treating mice chronically exposed to cigarette smoke with the complement inhibitor CR2-fH prevented smoke-induced retinal damage (Woodell et al., 2016).

6.3 Complement component knockout mice and aging

We and other groups have studied the combined effect of aging and complement deficiency on ocular phenotype in mouse models, attempting to link the age-associated risk of AMD with complement dysregulation (Coffey et al., 2007; Ding et al., 2015; Hoh Kam et al., 2013; Hoh Kam et al., 2016; Toomey et al., 2015). Initial investigation of aged (~2 year) Cfh−/− mice revealed that they had reduced scotopic electroretinograms, thinning of the outer nuclear layer and thinning of BrM (Coffey et al., 2007). Given the significant accumulation of lipid deposits in BrM seen in AMD (discussed above), thinning BrM in aged Cfh deficient mice was inconsistent with an AMD-like phenotype. However, subsequent analysis of Cfh deficient mice by our lab and Hoh Kam et al. (2013) showed that these mice indeed had thickened BrM and accumulation of basal laminar deposits compared to age-matched controls, showing that CFH influences the development of basal laminar deposits in vivo (Ding et al., 2015; Hoh Kam et al., 2013; Toomey et al., 2015). A study comparing the effect of rearing the mice in a pathogen free, barriered environment to a conventional open environment found that there was reduced pathology in the age-matched mice raised in a pathogen-free facility (Hoh Kam et al., 2016), which may have contributed to the lack of observed basal deposits in studies by Coffey et al. (2007). One study described C3 and C3b deposition on retinal vessels leading to decreased oxygen supply (Lundh von Leithner et al., 2009). Although our group has had trouble replicating increased C3 deposition in Cfh knockout mice, it is likely that CFH plays a complement dependent role in choroidal neovascularization (discussed further in section 6.5) (Ding et al., 2015; Toomey et al., 2015). In fact, using double knockout Cfh and C3 deficient mice Hoh Kam et al. showed that C3 deficiency did not facilitate the predicted rescue of the Cfh knockout ocular phenotype (Hoh Kam et al., 2013). The absence of CFH in Cfh knockout mice results in a functional deficiency of C3 in the circulation due to rapid consumption of C3b (Pickering et al., 2002; Toomey et al., 2015). Together our results support a role for CFH in regulating basal laminar deposit formation in vivo that is independent of its role in the complement cascade as detailed in the following section, although, some effects including visual function decline and RPE damage appear to occur in a complement-dependent manner (Toomey et al., 2015).

6.4 Multifactorial Mouse Model of Complement Dysregulation

Given the complexity of AMD pathogenesis, we developed a multifactorial, complement-dysregulated mouse model based on several risks associated with the human disease: advanced age, complement activation based on mouse Cfh gene knock out (Cfh−/−) or haploinsufficiency (Cfh+/−) (Pickering et al., 2002) and high fat, cholesterol-enriched (HFC) diet. Using this model we showed that Cfh+/− mice, when maintained on the HFC diet, exhibit a robust AMD-like ocular phenotype that includes formation of activated complement, basal laminar deposits, RPE cell pathology and visual function deficits (Fig. 8) (Toomey et al., 2015). Importantly, we showed that damage to the RPE layer and visual function decline was dependent on an intact complement cascade (Toomey et al., 2015). Remarkably, we additionally demonstrated that basal laminar deposit formation occurred in a CFH-dependent, but complement-independent manner (Toomey et al., 2015). Specifically, we found that there was greater basal laminar deposit accumulation in both the Cfh−/− and the Cfh+/− mice fed the HFC diet compared to age-matched normal C57BL/6 mice on HFC (Fig. 8A and B) (Toomey et al., 2015). This led us to hypothesize a non-canonical function of the CFH protein in regulating sub-RPE lipoprotein accumulation and basal laminar deposit formation (Toomey et al., 2015). Based on the assumption that sub-RPE deposit formation occurs following lipoprotein accumulation in BrM (Curcio et al., 2011), we showed that CFH and lipoproteins compete for novel binding sites in the HSPG-rich extracellular matrix of BrM (Fig. 9) (Toomey et al., 2015). We hypothesize that CFH and RPE-derived lipoproteins (potentially with oxidative modifications) interact at three-dimensional GAG motifs in BrM, which is altered by the CFH H402 polymorphism (Fig. 10). We propose that patients with the CFH H402 variant develop sub-RPE lipoprotein accumulation faster than patients with the CFH Y402 variant due to the reduced competition for GAG motifs in BrM by CFH H402. Consequently, increased BrM lipoprotein accumulation would lead to earlier development of drusen and resultant AMD pathology. Interestingly, individuals expressing the AMD-risk-associated CFH C1210 variant have increased macular drusen loads and develop later stages of AMD earlier than individuals with the R1210 variant (Ferrara and Seddon, 2015). This hypothesis provides a link between the CFH-binding properties altered by the Y402H polymorphism and the pathognomonic features of early AMD.

Figure 8.

Contrasting the ocular phenotypes of aged Cfh−/− and Cfh+/−~HFC mice shows a non-canonical function of CFH protein in regulating basal laminar deposit formation and complement-dependent impact on visual function decline. (A) Transmission electron micrographs showing basal laminar deposits along Bruch’s membrane (BrM, arrowhead). Large (>4mm high) deposits were often seen in the Cfh+/−~HFC and Cfh−/−~HFC mice. (B) Distribution of basal laminar deposit heights for the three mouse genotypes fed a HFC diet. These cumulative frequency curves illustrate the increased basal laminar deposit load present in both the Cfh−/− and Cfh+/− HFC-fed animals compared to wild type C57BL/6 HFC fed (B6~HFC) animals. Thus, mice with decreasing levels of CFH over the 8 week period of HFC diet challenge developed increased basal laminar deposit volumes, indicating that CFH plays a role in retarding basal laminar deposit formation (C) Scotopic electroretinogram (ERG) flash responses in wild type B6, Cfh+/− and Cfh−/− mice fed a normal diet (ND) or HFC diet. B6 and Cfh−/− mice showed no statistically significant depression of ERG amplitude with HFC diet. However, Cfh+/−~HFC mice showed a marked decrease in b-wave amplitude (middle graph). These data show that although Cfh+/− and Cfh−/− mice develop significant deposits only Cfh+/− mice, with an intact complement cascade, develop significant visual function loss. Data is presented as mean ± SE. * indicates post-hoc Tukey for a p<0.05 following a statistically significant genotype by diet interaction by ANOVA. N=6–8 per group. (Adapted from Toomey et al. PNAS 2015)

Figure 9.

CFH competes for lipoprotein-binding sites in BrM. (A–B) Human BrM samples from aged post-mortem donors were incubated with or without 1μM of human CFH protein. (A) Immunohistochemical staining for CFH (green) in the BrM samples. (B) FPLC fractionation of human BrM lysates shows endogenous lipoproteins present in aged BrM tissue are removed by the addition of CFH (1 μM CFH, green trace). The asterisk (*) indicates P < 0.05 for total cholesterol in each fraction comparing 0 μM CFH to 1 μM CFH (three independent experiments, each with n = 3) (From Toomey et al., PNAS 2015).

Figure 10.

Hypothesis linking CFH polymorphism and AMD pathobiology. Our group proposes that CFH and RPE-derived lipoproteins (with or without possible oxidative modifications) compete for binding sites in GAG motifs in BrM. Binding affinity for these sites differs in CFH Y402H variants such that decreased affinity in the H402 variant leads to increased lipoprotein accumulation in BrM and the formation of sub-RPE deposits (drusen).

Pierce and colleagues also tested the role of complement in basal laminar deposit formation in a mouse model of inherited macular dystrophy (Fernandez-Godino et al., 2015; Garland et al., 2014). Using a mouse model of inherited macular dystrophy (Doyne Honeycomb Retinal Dystrophy/Malattia Leventinese) caused by a mutation in EFEMP1 and in mouse RPE cell cultures these studies tested the effect of complement components on basal laminar deposit formation and showed that formation of deposits in vivo and in culture was mediated by C3a and not C5a (Fernandez-Godino et al., 2015; Garland et al., 2014). Our results in a separate model confirm that C5a does not appear to be involved in basal laminar deposit formation in mice (see below); furthermore, in vitro cigarette smoke extract exposure also appears to cause intracellular lipid accumulation that is dependent on C3aR (Kunchithapautham et al., 2014). The precise mechanism by which C3aR may affect sub-RPE deposit formation is unclear; however, Fernandez-Godino et al. proposed that the pro-inflammatory factors, IL-6 and IL-1-beta are involved in downstream events (Fernandez-Godino et al., 2015).

Calippe et al., have recently revealed an additional non-canonical role for CFH in inhibiting sub-retinal mononuclear phagocyte clearance in a Cx3cr1 model of chronic retinal inflammation and in Apolipoprotein E2 humanized transgenic mice (Calippe et al., 2017). The authors show that CFH via interaction with CD11b leads to reduced signaling through the TCD47-TSP1axis (Calippe et al., 2017). Most interestingly their paradigm predicts that the CFH protein promotes rather than protects against AMD pathology, a concept that has not been appreciated in many of the clinical studies and models involving CFH in AMD discussed above.

6.5 Effect of Targeting C5a in Mouse Models of AMD

Recently, our group has evaluated the role of C5a using systemic delivery of a monoclonal antibody targeting C5a. We show that anti-C5a appears to regulate monocyte and mononuclear phagocyte populations in the choroid in the setting of chronic complement dysregulation seen in the Cfh+/−~HFC model. Anti-C5a has anti-exudative properties relevant to the treatment of “wet” AMD, but does not appear to be capable of preventing basal laminar deposits, RPE damage or visual function decline seen in our model of early AMD (Toomey et al. 2017, in review). The anti-exudative properties of C5a were previously shown in several studies relying on the CNV laser model that implicated C5a in acute inflammation in the chorioretinal environment (Coughlin et al., 2016; Nozaki et al., 2006). Nozaki et al. proposed a role for C5a in recruiting monocytes and in production of VEGF contributing to CNV (Nozaki et al., 2006). We suspect that this monocyte recruitment is secondary to activation of adhesion molecules on choroidal endothelial cells by C5a (Skeie et al., 2010). Coughlin et al., propose that gamma-delta T-cells and IL-17 production in the choroid are dependent on C5a following laser-induced CNV (Coughlin et al., 2016). While these studies support a therapeutic advantage of anti-C5a for wet AMD based on its effects in the laser-induced CNV model, its effects on chronic inflammatory stress from complement activation in the chorioretinal environment underlying dry AMD pathobiology had not been addressed.

6.6 Modeling the CFH H402 variant in vivo

6.6.1 Chimeric transgenic CFH SCR6–8 expression driven by mouse ApoE promoter

The first study to model the CFH 402 variant in mouse was published by Ufret-Vincenty et al. in 2010. The authors used transgenic mice expressing the human CFH sequence for SCRs 6–8 (with either the Y402 or H402 variant), flanked by the mouse sequence for SCRs 1–5 and SCRs 9–20 under the control of the mouse apoE promoter crossed onto the Cfh knockout background (Ufret-Vincenty et al., 2010). They showed that this results in stable expression of chimeric CFH proteins in relevant tissues, liver and whole eye, and functional rescue of peripheral complement deficiencies seen in Cfh knockout mice. However, both the CFH H402 and CFH Y402 chimeric transgenic animals showed evidence of ocular pathology compared to wild type C57BL/6 controls, particularly accumulation of sub-retinal Iba1+ cells and basal laminar deposits (Ufret-Vincenty et al., 2010). This is unexpected since the Y402 variant of CFH is not associated with risk in human and the H402 variant, though associated with AMD risk in humans, is not a mutation, but is a common variant strongly associated with AMD risk and therefore does not singularly cause AMD pathology. The same group proposed this model could be used to investigate the role of altered protein-protein interactions in vivo. Chimeric SCRs 6–8 yielded interesting observations regarding the interaction of SCRs 6–8 and malondialdehyde (MDA) -modified proteins discussed earlier (Aredo et al., 2015).

6.6.2 Transgenic full-length CFH expression using bacterial artificial chromosomes

In 2015, our group published the ocular phenotype of transgenic mice created using gene constructs expressing full-length human CFH. Human bacterial artificial chromosomes (BAC) containing the CFH Y402 or CFH H402 gene variant were used to generate transgenic mice expressing the full-length Y402 and H402 variants of human CFH. These mice were then crossed with Cfh knockout mice to generate transgenic mice that were hemizygous (one human CFH gene and no copies of the mouse Cfh gene), and expressed the Y402 or H402 variant of human CFH but no murine CFH (Ding et al., 2015). We showed that the human CFH is expressed in relevant tissues, including the liver, kidney and eye, but at significantly lower levels than CFH in wild type mice. Expression of human CFH Y402, but not CFH H402, rescues the kidney phenotype seen in Cfh knockout mice (Ding et al., 2015). The CFH H402 mice also develop basal laminar deposits (Ding et al., 2015). However, these differences between the Y and H402 expressing mice were complicated by the fact that the CFH Y402 Cfh knockout mouse (CFH Y402:Cfh−/−) expresses 2-fold greater levels of CFH compared to the CFH H402 Cfh knockout mouse (Ding et al., 2015). In order to remove the confounding effect of different levels of expression of CFH in these mice, CFH H402:Cfh−/− mice were crossed to generate homozygous CFH HH402:Cfh−/− mice that express the same levels of CFH as the hemizygous CFH Y402:Cfh−/− animals (Ding et al., 2015). This increased expression of the H402 variant of CFH is sufficient to rescue these mice from the kidney damage seen in Cfh−/− and CFH H402:Cfh−/− mice (Ding et al., 2015). Work is now underway to definitively determine if expression of the AMD risk-associated H402 variant compared to the Y402 CFH leads to an AMD-phenotype in our multifactorial mouse model that invokes human CFH expression, advanced age and a high fat, cholesterol-enriched (HFC) diet.

7. Human Studies Implicating Complement Damage in AMD

Several groups have sought to relate circulating plasma levels of complement activation products and AMD. Two groups showed that increased levels of complement breakdown products, Factor Bb and C5a were independently associated with AMD (Reynolds et al., 2009; Silva et al., 2012). In addition, local complement activation was described in patients with AMD and accumulation of complement activation byproducts have been detected in drusen (Hageman et al., 2001; Loyet et al., 2012; Mullins et al., 2011; Mullins et al., 2014). MAC formation was increased in AMD patients compared to controls and appears to be primarily concentrated in the choriocapillaris and capillary pillars (Mullins et al., 2014). MAC also appears to be increased in the choriocapillaris of patients with the CFH Y402H polymorphism (Mullins et al., 2011). Furthermore, increased levels of the complement breakdown product C3a were detected in BrM/choroid extracts with increasing histological grade of AMD pathology in post-mortem tissue (Loyet et al., 2012).

There are two major effector functions of the complement cascade: (1) the formation of the MAC, resulting in cell lysis, and (2) the formation of the anaphylatoxins, C3a and C5a, resulting in immune cell recruitment (Sarma and Ward, 2011). Immunohistochemical analysis of MAC in RPE/choroid of AMD patients revealed that although significant MAC is found on and around drusen, it is generally not detected in association with RPE cell surfaces (Johnson et al., 2000; Mullins et al., 2011). It is thought that, due to the high levels of membrane-bound complement inhibitors, RPE are sufficiently protected from MAC formation (Yang et al., 2009). A series of experiments by Mullins and colleagues have investigated the role of MAC in AMD. Whitmore et al. proposed a model of AMD pathogenesis centering around MAC formation in the aging choriocapillaris (recently reviewed in (Whitmore et al., 2015)). Studies by this group have shown that MAC forms with age in the choriocapillaris and this is exacerbated in people with the CFH H402 variant (Mullins et al., 2011; Mullins et al., 2014). They propose that chronic MAC formation leads to vascular loss in the choroid, impacting the blood supply to BrM, the RPE and photoreceptors (Whitmore et al., 2015). In fact, hypoxia-induced metabolic stress has been shown to be sufficient to produce photoreceptor degeneration in mice (Kurihara et al., 2016). Due to the lack of an anti-mouse C5b-9 antibody, hypothesis driven experiments evaluating the role of MAC formation in either the RPE or choriocapillaris in mouse models has been difficult.

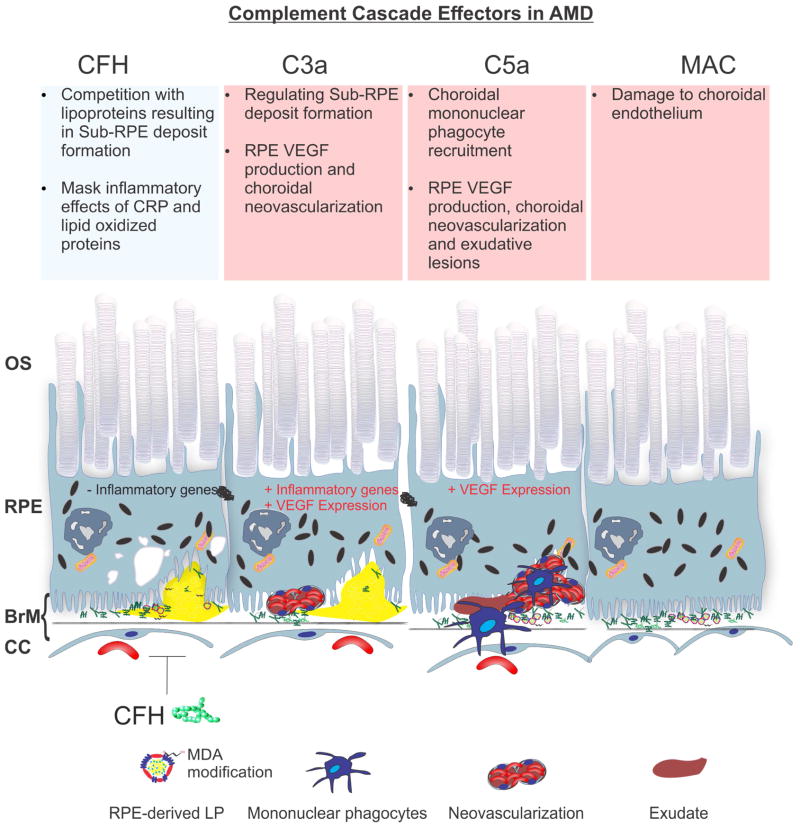

Collectively, a variety of studies have provided insight into the role specific effector functions of the complement cascade in AMD. Based on the findings in humans by Whitmore et al. (Whitmore et al., 2015), a hypothesis emerges in which MAC formation leads to significant damage to the choroidal endothelium and decreased blood supply to the RPE in mouse models as well. Decreased blood supply could lead to RPE hypoxia and subsequent damage to the RPE and photoreceptors (as suggested by the work in mouse by Kurihara et al. (Kurihara et al., 2016)). It appears that C5a plays a role in mononuclear phagocyte recruitment and choroidal neovascularization; whereas, C3a (Fernandez-Godino et al., 2015) and CFH (Toomey et al., 2015) play roles in sub-RPE deposit formation and choriocapillaris MAC formation (Whitmore et al., 2015) that may lead to choriocapillaris damage and visual function decline (Kurihara et al., 2016) (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Complement damage and AMD pathobiology. Analysis of human post-mortem tissue, mouse models and in vitro assays have elucidated that different components of the complement cascade appear to regulate or stimulate specific pathobiology in AMD. From left to right, CFH appears to influence sub-RPE deposit formation and RPE inflammatory responses, C3a appears to act as stimulus for sub-RPE deposit formation, RPE inflammatory responses and neovascularization, C5a appears to stimulate RPE inflammatory responses, mononuclear phagocyte recruitment, neovascularization and exudative lesions; MAC appears to mediate the destruction of choroidal endothelium and the formation of ghost capillaries in the choriocapillaris.

8. Summary and Future Directions

AMD is a complex multifactorial disease characterized in its early stages by lipoprotein accumulations in BrM and in its late forms by neovascularization (“wet” form) or geographic atrophy of the RPE cell layer (“dry” form). Genetic studies have strongly supported a relationship between the alternative complement cascade, including the common CFH H402 variant, and development of AMD. In the past decade, research has shown functional differences in the CFH H402 variant in terms of CRP binding, masking of lipoprotein peroxidation epitopes and binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. New data from ex vivo binding assays, in vivo mouse models and postmortem human tissue indicate that the CFH H402 variant may have reduced affinity for heparan sulfate proteoglycans leading to lipoprotein accumulation in BrM and ensuing drusen progression. The roles of additional complement components, including C3a, C5a and MAC, in AMD pathobiologies are also under investigation, as are ongoing studies in transgenic mice attempting to model effects of the H402 variant in CFH.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the funding support from the National Institutes of Health (EY026161 to CBR), P30 EY005722 (to V. Arshavsky), and T32 GM007171-Medical Scientist Training Program (to C.B.T.), an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (to the Duke Eye Center), and a grant from the Foundation Fighting Blindness (C.B.R).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abecasis GR, Burt RA, Hall D, Bochum S, Doheny KF, Lundy SL, Torrington M, Roos JL, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M. Genomewide scan in families with schizophrenia from the founder population of Afrikaners reveals evidence for linkage and uniparental disomy on chromosome 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:403–417. doi: 10.1086/381713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research G. Lutein + zeaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids for age-related macular degeneration: the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309:2005–2015. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research G. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1417–1436. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DH, Mullins RF, Hageman GS, Johnson LV. A role for local inflammation in the formation of drusen in the aging eye. American journal of ophthalmology. 2002;134:411–431. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DH, Radeke MJ, Gallo NB, Chapin EA, Johnson PT, Curletti CR, Hancox LS, Hu J, Ebright JN, Malek G, Hauser MA, Rickman CB, Bok D, Hageman GS, Johnson LV. The pivotal role of the complement system in aging and age-related macular degeneration: hypothesis re-visited. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2010;29:95–112. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari M, McKeigue PM, Skerka C, Hayward C, Rudan I, Vitart V, Polasek O, Armbrecht AM, Yates JR, Vatavuk Z, Bencic G, Kolcic I, Oostra BA, Van Duijn CM, Campbell S, Stanton CM, Huffman J, Shu X, Khan JC, Shahid H, Harding SP, Bishop PN, Deary IJ, Moore AT, Dhillon B, Rudan P, Zipfel PF, Sim RB, Hastie ND, Campbell H, Wright AF. Genetic influences on plasma CFH and CFHR1 concentrations and their role in susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4857–4869. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aredo B, Li T, Chen X, Zhang K, Wang CX, Gou D, Zhao B, He Y, Ufret-Vincenty RL. A chimeric Cfh transgene leads to increased retinal oxidative stress, inflammation, and accumulation of activated subretinal microglia in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:3427–3440. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-16089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augood CA, Vingerling JR, de Jong PT, Chakravarthy U, Seland J, Soubrane G, Tomazzoli L, Topouzis F, Bentham G, Rahu M, Vioque J, Young IS, Fletcher AE. Prevalence of age-related maculopathy in older Europeans: the European Eye Study (EUREYE) Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:529–535. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.4.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty S, Koh H, Phil M, Henson D, Boulton M. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;45:115–134. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird AC, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, Chisholm IH, Coscas G, Davis MD, de Jong PT, Klaver CC, Klein BE, Klein R, et al. An international classification and grading system for age-related maculopathy and age-related macular degeneration. The International ARM Epidemiological Study Group. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39:367–374. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80092-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JR, Clark SJ. Age-related macular degeneration: genome-wide association studies to translation. Genet Med. 2016;18:283–289. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black S, Kushner I, Samols D. C-reactive Protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48487–48490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaum BS, Hannan JP, Herbert AP, Kavanagh D, Uhrin D, Stehle T. Structural basis for sialic acid-mediated self-recognition by complement factor H. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:77–82. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora NS, Kaliappan S, Jha P, Xu Q, Sohn JH, Dhaulakhandi DB, Kaplan HJ, Bora PS. Complement activation via alternative pathway is critical in the development of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization: role of factor B and factor H. J Immunol. 2006;177:1872–1878. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]