Abstract

We conducted a prospective clinical study (n=14; 29% female) to assess the accuracy of a three-dimensional (3D) photography-based method of torso geometry reconstruction and body surface electrodes localization. The position of 74 body surface electrocardiographic (ECG) electrodes (diameter 5 mm) was defined by two methods: 3D photography, and CT (marker diameter 2 mm) or MRI (marker size 10×20 mm) imaging. Bland-Altman analysis showed good agreement in X (bias −2.5 [95% limits of agreement (LoA) −19.5 to 14.3] mm), Y (bias −0.1 [95% LoA −14.1 to 13.9] mm), and Z coordinates (bias −0.8 [95% LoA −15.6 to 14.2] mm), as defined by the CT/MRI imaging, and 3D photography. The average Hausdorff distance between the two torso geometry reconstructions was 11.17 ± 3.05 mm. Thus, accurate torso geometry reconstruction using 3D photography is feasible. Body surface ECG electrodes coordinates as defined by the CT/MRI imaging, and 3D photography, are in good agreement.

Keywords: ECG recording, electrode position, ECG imaging

Introduction

Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging (ECGi) is a promising novel approach to study arrhythmogenic substrate of cardiac arrhythmias in humans [1, 2]. In the future ECGi can become a useful clinical tool, and its potential clinical applications are currently being actively studied[2]. The ECGi method uses electrocardiographic (ECG) unipolar potentials recorded on the body surface and individual heart-torso geometry, to reconstruct unipolar potentials on the epicardial surface of the heart. Accurate acquisition of patient-specific heart-torso geometry relationships, as well as proper registration of the ECG electrode positions on the body surface are necessary to minimize the error in computational procedures of the ill-posed inverse problem[3]. In addition, body surface potential maps have been previously used to develop algorithms to non-invasively identify the location of cardiac arrhythmia sources [4–6]. Body surface potential (BSP) maps are based on three dimensional (3D) computational structures and multi-electrode systems. Accurate acquisition of a patient specific torso geometry as well as proper registration of the ECG electrodes’ position on the body surface is necessary to minimize errors in computational procedures.

Torso geometry could be evaluated using several imaging modalities. Non-contrast chest Computed Tomography (CT) is frequently used in conjunction with X-ray-opaque Ag/AgCl electrodes[1]. The advantage of such approach is the simultaneous and accurate acquisition of body-surface electrodes location, this type of imaging is associated with fairly low radiation exposure[2].

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an attractive alternative to CT [7], as it does not utilize ionizing radiation. However, MRI is contra-indicated to certain patients with non-MRI safe metallic hardware. The axial spatial resolution of MRI is lower than CT. Acquisition of both torso and heart geometry requires additional time in the scanner, which is associated with increased patient discomfort from breath-holds, and increased the cost of the MRI data acquisition. Due to distortion of ECG signal by the magnet, ECG-gating at a specific phase of the cardiac cycle is problematic. Moreover, use of MRI makes simultaneous acquisition of the body surface electrodes position challenging, and increases the cost of the procedure due to specific requirements for MRI-opaque body surface electrodes.

Developing a low cost and accurate non-invasive technique to reconstruct the full torso geometry and electrode position without extra CT/MRI imaging will be crucial to improve BSP and ECGi clinical studies. This could be used in conjunction with cardiac clinical CT/MRI imaging data, and it could decrease the use of invasive methods exposure, patient discomfort, and the cost of each procedure.

Fluoroscopy-based heart surface geometry reconstruction and photography-based method to localize the three-dimensional (3D) coordinates of body surface ECG electrodes has been proposed and validated previously in a phantom study [8]. More recently, use of 3D Kinect (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) camera was suggested to have potential to provide 3D geometrical information [9]. However, accuracy of the 3D Kinect camera-based method of torso geometry reconstruction and body surface electrodes localization has not been previously studied. The goal of this study was to assess the accuracy of the 3D Kinect camera-based method for torso geometry reconstruction and body surface electrode localization in a clinical setting.

Methods

Patient population

We conducted the clinical study at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board. All study participants agreed to participate and signed an informed consent form. OHSU patients (individuals under clinical cardiovascular care at OHSU Healthcare System) were included in this study. Exclusion criteria were: (1) age < 18 years, (2) pregnancy, (3) clinical contraindications for CT and MRI.

Body surface potential recording

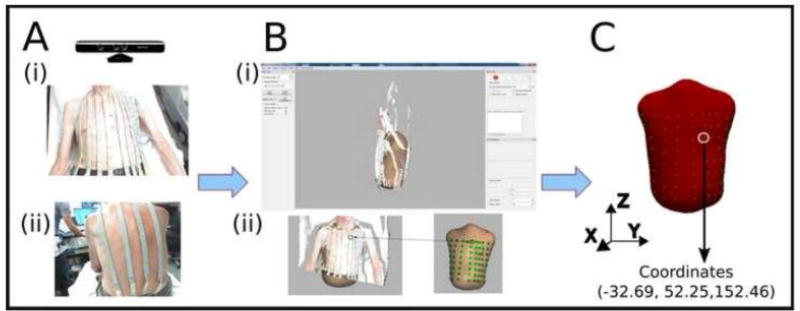

Unipolar ECG potentials were recorded on the body surface using 128 Ag/AgCl electrodes (4 panels of 32 electrodes; each panel is arranged as four strips of 8-electrodes), as shown in the Figure 1A. The diameter of the ECG electrodes was 5 mm. ActiveTwo biopotential measurement system (BioSemi, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) was used for recording. The Kinect camera was placed in a structure to keep it steady and control any inclination angle. Each measurement took an average of 15 minutes in total after all the electrodes were placed.

Figure 1. Kinect camera 3D torso mesh and electrodes position reconstruction process.

A) Frontal (i) and posterior (ii) view of 128 electrodes placed on the surface of the torso. B) 3D torso mesh (i) and electrodes position (ii) reconstruction. C) 3D mesh and XYZ Cartesian coordinates identification.

ECG electrodes localization using 3D photographic camera

Images of the front, back, left and right side of the torso with ECG electrodes applied were recorded with a Kinect camera V1 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) using commercial software PeacsKinect (Peacs BV, Arnhem, the Netherlands) as shown in Figure 1. The distance between the camera and patient torso was recorded.

ECG electrodes localization using MRI or chest CT

After ECG potentials had been recorded on the body surface, the ECG electrodes were removed from the torso of the patient, and 5 to 10 MRI- or CT- specific markers were placed on each patient’s chest, to mark electrode localization (Figure 2A and 3A) accurately. Six patients underwent MRI, while eight underwent CT scan. The diameter of the CT markers (N-Spot, Berkley Medical, The Hague, The Netherlands) was 2.0 mm (Figure 2A-ii), whereas MRI markers (Spee-D-Mark, The St. John Companies, Valencia, Spain) were larger (10 mm width × 20 mm length; Figure 3A-ii). CT in-plane resolution was 0.5 mm, and axial resolution was 0.6 mm. Siemens TIM Trio 3 Tesla with VB17 software was used for MRI.

Figure 2. CT scan 3D torso mesh and electrodes position reconstruction process.

A) Image of CT markers placed on the surface of the torso. B) 3D torso mesh reconstruction from representative CT scan images. C) XYZ coordinates identification from the reconstructed 3D structures, with the depth parameter as the X-axis, the width as the Y-axis and the height as the Z-axis.

Figure 3. MRI scan 3D torso mesh and electrodes position reconstruction process.

A) Image of (i) MRI and (ii) MRI markers placed on (iii) the surface of the torso. B) 3D torso mesh reconstruction from representative MRI scan images. C) XYZ coordinates identification. X, Y, and Z axes as defined in Figure 2 legend.

3D torso and electrodes location reconstruction using 3D photographic camera

Each image was placed on top of a generic mesh. Using the distance recorded and the ‘modify torso’ PeacsKinect software (Peacs BV, Arnhem, the Netherlands) option, the size of the generic 3D torso was semi-automatically adjusted to match the patient’s torso size (Figure 1B-i). Then, the ‘biosemi_128’ option was selected which allows the adjustment of the electrode positions in the 3D mesh. By visually comparing the position of the electrodes in the images with the electrodes points in the mesh, each electrodes location was found (Figure 1B-ii). Therefore, 3D torso mesh and electrode positions for each patient were manually constructed from images recorded with the Kinect camera using commercial software PeacsKinect (Peacs BV, Arnhem, the Netherlands) (Figure 1C). The X-axis reflected depth, the Y-axis reflected width, and the Z-axis reflected the height of a photographed 3D object.

3D torso and electrodes position reconstruction using MRI or CT

The 3D torso meshes were reconstructed from MRI/CT imaging data using the software ITK-snap (PICSL, USA) [10]. As the data obtained from cardiac MRI/CT-scans procedure did not include slices of the full torso, only a partial torso mesh was created (Figure 2B and 3B). Using the ‘snake’ ITK-snap option, a greyscale pixel value was selected as a lower threshold to automatically reconstruct the 3D torso geometry using region growing [10]. After torso reconstruction, MRI/CT markers were identified from the 3D reconstructed meshes (Figure 2C and Figure 3C), with the depth parameter as the X-axis, the width as the Y-axis and the height as the Z-axis.

Inter- and intra- observer variability test

As this is the first study testing the feasibility and accuracy of the 3D technology for reconstructing a torso surface and electrode position, both inter- and intra- observer variability test were performed. The intra-observer test consisted of the same user creating the torso mesh and electrode position twice from the same 3D photographic data for each patient. The inter-observer test consisted of a different user creating the torso mesh and electrode position from the same 3D photographic data for each patient without previous knowledge of the first reconstruction. As the MRI and CT scan meshes and electrode position were obtained automatically, no variability test was performed for this data.

Comparison of the differences in the torso meshes created using 3D photographic camera images vs. MRI/CT images

Hausdorff distance was used to compare the two meshes reconstructed for each patient. Hausdorff distance is the greatest of all distances measured from an element in one mesh to the closest element in another mesh [11] and has been used in previous studies to compare two different sets of 3D computational structures [12]. Custom Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) software was created to calculate Hausdorff distance after placing both meshes in the same XYZ-coordinate system, and ensuring the origin was located in the center of the torso using anatomical identifiers such as shoulder and chest position. Hausdorff distance was calculated using the equation [11, 12]

| (1) |

where d is the distance between the element a in mesh A and element b in mesh B. Due to the asymmetry of equation (1) and the MRI/CT scan meshes being considerably shorter in the axial/height axis (Z-axis) compared to the 3D photographic camera, the Hausdorff distance was calculated only from CT/MRI mesh to 3D photographic camera mesh.

Comparison of the differences in the electrodes position localized using 3D photographic camera images vs. MRI/CT images

After placing both meshes in the same Cartesian coordinate system with axes (Figure 4), XYZ-coordinates corresponding to the electrodes and markers were extracted using a code in Matlab from each torso mesh reconstructed with both methods. The XYZ coordinate of the center of the marker was used in both MRI and CT cases (Figure 2C-ii and Figure 3C-ii). Each coordinate represents a direction: Z is the vertical axis, Y is the horizontal axis and X the depth axis (Figure 4).

Figure 4. 3D photographic and MRI/CT torso mesh and electrodes position reconstruction.

A) Overlap of the CT and 3D photographic meshes, electrodes and markers. B) MRI and 3D photographic meshes, electrodes and markers. The markers and electrodes taken for comparison are showed in a blue circle. X, Y, and Z axes as defined in Figure 2 legend.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for the Hausdorff distance is reported for each patient. Distribution of each variable was tested for normality. To normalize the distribution of a variable, if needed, we selected transformation, which resulted in the minimum chi-squared value. To normalize the distribution of maximum Hausdorff distance, we performed the inverse cubic transformation. To normalize the distribution of minimum Hausdorff distance, square root transformation was performed. We compared mean, minimum, and maximum Hausdorff distance in subgroups of males vs. females, and in participants for whom the torso geometry obtained using CT vs. MRI imaging. A two-sample t-test on the equality of means with unequal variances was used to compare normally distributed variables.

Bland-Altman analysis [13] and Lin’s concordance analysis [14] were used for the assessment of agreement of each electrode coordinates obtained by the two methods for each patient. The degree of agreement was expressed as the bias (the mean difference) with 95% limits of agreement (mean±2 standard deviations). Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient ρc was calculated to describe the strength of agreement: >0.99 indicated almost perfect agreement; 0.95–0.99, indicated substantial agreement. Pearson’s correlation coefficient r was calculated, as well. Bradley-Blackwood procedure was used to simultaneously compare the means and variances of the two measurements[15]. A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant. STATA 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) was used for analysis.

Results

Study Population

The study population consisted of 14 individuals (10 males and four females); mean age was 63.4 ±12.8 years; body mass index was 31.74 ± 9.54 kg/m2. In all study participants, there were 74 ECG electrodes localized by both methods (average 5.3 electrodes per patient).

The mean vertical distance between electrodes in each strip was 15mm. The horizontal distance between electrode strips varied depending on the patient body morphology, it ranged from 50mm to 100mm.

Differences in the torso meshes created using 3D photographic camera images vs. MRI/CT images

The average Hausdorff distance between the two torso geometry reconstructions was 11.17 ± 3.05 mm (range 7.54 – 17.52 mm; Table 1). The minimum Hausdorff distance was nearly zero, whereas the average maximum Hausdorff distance was 63.6±29.3 mm. There were no statistically significant differences in the minimum, maximum, or mean Hausdorff distance between males and females (Table 2). The maximum Hausdorff distance in the subgroup of patients for whom MRI was used for the torso geometry reconstruction was significantly larger than in patients for whom CT was used (Table 2). Similarly, there was a trend towards larger minimum Hausdorff distance in the subgroup using the MRI imaging modality, as compared to CT. No other differences between the subgroups were observed.

Table 1.

Hausdorff distance in the study participants.

| Patient ID |

Imaging type |

Gender | Minimum distance (mm) |

Maximum distance (mm) |

Mean distance (mm) |

RMS_dis (mm) |

Min (%) | Max (%) | Mean(%) | RMS(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 | MRI | m | 0.000046 | 55.92 | 9.99 | 13.66 | 0 | 11.8 | 2.11 | 2.89 |

| 102 | MRI | m | 0.000397 | 56.22 | 17.52 | 21.031 | 0.0001 | 10.64 | 3.33 | 3.98 |

| 103 | MRI | m | 0.00015 | 44.84 | 13.62 | 16.11 | 0 | 8.6 | 2.62 | 3.1 |

| 104 | MRI | m | 0.0008 | 39.77 | 9.92 | 12.84 | 0 | 7.5 | 1.8 | 2.4 |

| 105 | MRI | f | 0.00015 | 38.62 | 8.51 | 11.4 | 0 | 7.5 | 1.6 | 2.2 |

| 106 | CT | m | 0.00015 | 44.05 | 10.55 | 12.7 | 0 | 8.2 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| 107 | CT | f | 0.000001 | 70.37 | 13.96 | 18.07 | 0 | 10.53 | 2.09 | 2.7 |

| 108 | CT | m | 0.00031 | 125.06 | 8.85 | 11.14 | 0 | 21.26 | 1.5 | 1.89 |

| 109 | MRI | m | 0.00053 | 44.29 | 10.35 | 13.72 | 0 | 8.5 | 1.9 | 2.63 |

| 110 | CT | m | 0.00015 | 115.82 | 10.95 | 17.56 | 0 | 19.47 | 1.84 | 2.95 |

| 111 | CT | m | 0.000001 | 51.04 | 8.31 | 11.38 | 0 | 8.36 | 1.6 | 1.86 |

| 112 | CT | f | 0.000001 | 49.49 | 10.27 | 12.75 | 0 | 8.55 | 1.77 | 2.2 |

| 113 | CT | m | 0.00015 | 50.41 | 7.54 | 10.64 | 0 | 8.47 | 1.26 | 1.79 |

| 114 | CT | f | 0.00015 | 104.22 | 16.13 | 19.27 | 0 | 14.79 | 2.28 | 2.73 |

|

| ||||||||||

| AVERAGE | 0.000213 | 63.58 | 11.17643 | 14.44793 | 7.14E-06 | 11.01214 | 1.971429 | 2.544286 | ||

Hausdorff minimum (Min_dist), maximum (Max_dist), mean (Mean_dist) and root median square (RMS_dist) distance in millimeters (mm) and percentage (%) of each patient.

Table 2.

Comparison of the Hausdorff distance in males vs. females, and in the study subgroups by the type of imaging modality (MRI or CT) used for the torso geometry reconstruction.

| Variable | Males (n=10) |

Females (n=4) |

P- value |

MRI (n=6) | CT (n=8) | P- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Hausdorff distance, mean±SD, mm | 10.8±2.9 | 12.2±3.5 | 0.491 | 11.7±3.3 | 10.8±2.9 | 0.637 |

| Sqrt-transformed minimum Hausdorff distance, mean±SD | 0.014±0.008 | 0.006±0.007 | 0.101 | 0.017±0.008 | 0.008±0.007 | 0.060 |

| Inverse cubic transformed maximum Hausdorff distance, mean±SD | 7.8*10−6 ± 4.9*10−6 | 7.3*10−6 ± 7.4*10−6 | 0.914 | 1.1*10−5 ± 4.9*10−6 | 5.0*10−6 ± 4.3*10−6 | 0.034 |

Differences in the electrodes position, localized using 3D photographic camera images vs. MRI/CT images

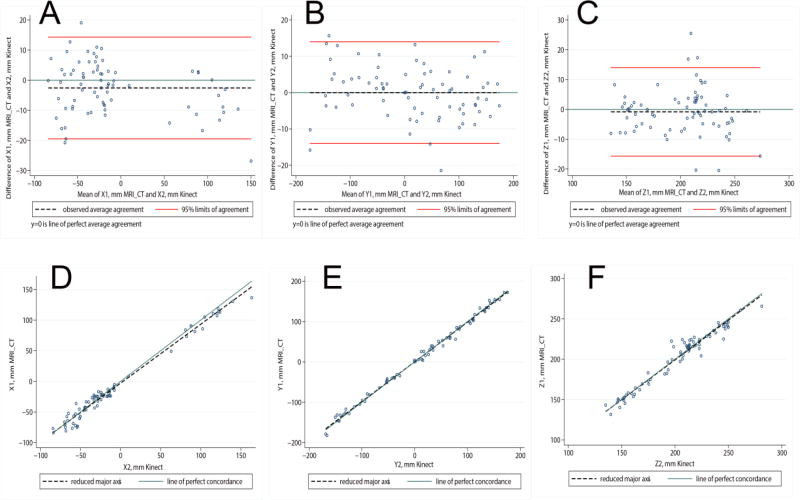

Results of the Bland-Altman analysis of agreement in XYZ-coordinates of ECG electrodes as localized by 3D photographic camera versus MRI/CT imaging are shown in Figure 5 and Table 3. The largest bias of 2.5 mm was observed for X-axis coordinates (Table 3), with 95% limits of agreement from −19.5 to 14.3 mm (Figure 5). While bias for Y and Z coordinates was smaller than that for X coordinates, 95% limits of agreement exceeded 10 mm for all XYZ coordinates. A wider range of 95% limits of agreement was observed for comparison of XYZ coordinates obtained by MRI imaging versus 3D photography, than for comparison of XYZ coordinates obtained by CT imaging versus 3D photography (Table 3). Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient (Figure 5 and Table 3) reported substantial agreement for all XYZ coordinates. Bradley-Blackwood F test was not significant for Y and Z coordinates, which confirmed that bias did not depend on average Y and Z coordinates. Therefore, the bias and 95% limits of agreement adequately described the differences between Y and Z coordinates. Bradley-Blackwood F test was significant for the X-axis coordinates, suggesting that the X-axis bias was dependent on the average X-axis coordinate, which challenged the interpretation of the X-axis coordinate agreement analysis.

Figure 5.

Bland-Altman plots demonstrating agreement of averaged X(A), Y(B), and Z(C) coordinates measured by two methods (3D photography vs. CT or MRI imaging). The scatterplot presents paired differences (Y axis), plotted against pair-wise means (X axis). The reference line indicates the perfect average agreement, Y=0. The central dashed line indicates the mean difference between the 2 measurements, or mean bias. Upper and lower lines represent the mean ± 2 standard deviations, or 95% limits of agreement. Concordance scatterplots of the average X(D), Y(E), and Z(F) coordinates, measured by two methods (3D photography vs. CT or MRI imaging). The reduced major axis of the data goes through the intersection of the means and has the slope given by the sign of Pearson's r and the ratio of the standard deviations (dashed line). The reference line shows the perfect concordance, Y=X.

Table 3.

Agreement of the body surface electrodes coordinates (n=74) localized by the MRI/CT imaging vs 3D photography.

| Coordinate | MRI/CT (mean ± SD) |

Kinect (mean ± SD) |

Bias | 95% Limits of Agreement |

Pearson, r |

Lin’s, ρc |

Bradley- Blackwood F(P) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants | X-axis, mm | −11.09 ± 60.42 | −8.52 ± 62.9 | −2.5 | −19.5 to 14.3 | 0.991 | 0.989 | 6.8 (0.002) |

| Y-axis, mm | 13.14 ± 97.35 | 13.16 ± 98.9 | −0.1 | −14.1 to 13.9 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 1.8 (0.179) | |

| Z-axis, mm | 200.73 ± 34.27 | 201.56 ± 34.75 | −0.8 | −15.6 to 14.2 | 0.976 | 0.976 | 0.6 (0.556) | |

|

| ||||||||

| MRI | X-axis, mm | −18.9 ± 50.8 | −19.2 ± 54.4 | 0.3 | −14.9 to 15.5 | 0.991 | 0.989 | 4.6(0.02) |

| Y-axis, mm | 19.4 ± 109.0 | 19.4 ± 110.6 | 0.09 | −14.4 to 14.6 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.8(0.47) | |

| Z-axis, mm | 209.9 ± 28.9 | 210.3 ± 30.3 | −0.3 | −17.8 to 17.1 | 0.956 | 0.955 | 0.4(0.62) | |

|

| ||||||||

| CT | X-axis, mm | −4.0 ± 67.8 | 1.1 ± 68.9 | −5.1 | −22.1 to 11.8 | 0.992 | 0.989 | 7.2(0.002) |

| Y-axis, mm | 7.5 ± 86.6 | 7.6 ± 88.2 | −0.1 | −13.8 to 13.6 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 1.0(0.37) | |

| Z-axis, mm | 192.5 ± 36.9 | 193.7 ± 37.0 | −1.3 | −13.6 to 11.0 | 0.986 | 0.958 | 0.8(0.47) | |

Inter- and intra- observer variability

The inter- and intra- observer variability for the Hausdorff distance between the reconstructed meshes showed a satisfactory agreement (Supplemental Table 1). The average mean distance values were 11.18 ± 2.56 mm and 14.32 ± 3.98 mm for the intra- and inter-observer test, respectively (Supplemental Table 1). The X, Y and Z coordinate of the electrode position obtained in inter- and intra- observer test showed satisfactory level of agreement with high Pearson and Lin’s correlation coefficients (Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion

Our prospective clinical study demonstrated the feasibility of the torso geometry reconstruction and body surface electrodes localization using 3D photography. This study does not intend to replace MRI or CT in the acquisition of a cardiac surface; however, it does provide information on the use of a 3D photographic method for reconstructing a torso surface geometry and electrode position. Two major aspects of the 3D photographic method were studied independently in this work: the accuracy of the method to create a 3D torso mesh, and the accuracy of the method to locate the electrode position. Both aspects were measured against the gold standard techniques of MRI or CT imaging. The meshes were compared by computing the Hausdorff distance between each node of the two meshes created. The electrode position was evaluated by comparing the spatial coordinates of each electrode form the two different reconstruction datasets.

We found substantial agreement in body surface ECG electrode coordinates as defined by the CT or MRI imaging, and 3D photography. Consistently, torso meshes created using 3D photography were in substantial agreement with the torso meshes created using CT or MRI imaging. Our work contributes towards the further development of the ECGi technology, as it is the first study providing information about the accuracy of the new method in a clinical setting. Use of the 3D photographic camera for the torso geometry reconstruction and body surface electrodes localization is safe, inexpensive, and time-efficient. Further development of a 3D photography – based approach will facilitate implementation of the ECGi method in clinical practice.

3D photography: new avenue for the torso geometry reconstruction

The Kinect camera uses a tiny laser-diffuser emitter. The laser emits infrared light, and the diffuser bears a binary speckle pattern. Invisible to human eyes an infrared speckle pattern is generated and projected onto the scene. The Kinect camera utilizes computational depth sensing where: it computes the depth once the deformed speckle pattern is captured, providing about 1mm accuracy at a distance of approximately 1m. In our study, we used the Kinect camera V1.0 (the 1st generation). The accuracy of the depth sensing was significantly improved in the Kinect camera V2.0 (2nd generation), due to increased efficiency of space-time multiplexing[16]. Future use of the Kinect V2.0 should further improve the accuracy of the measurements and the torso geometry reconstruction, and it should be studied further.

The 3D photographic method does not intend to replace MRI/CT scan in ECGi methodology, as no information about the heart geometry can be acquired using 3D photography technology. Therefore, MRI/CT images are still needed for ECGi. However, combining the 3D photography-based torso geometry with the cardiac CT/MRI- based heart geometry could provide a way to continue using high-resolution cardiac images and full torso geometry, while improving the safety profile of the procedure, comfort of the patients, and reducing overall cost, as CT/MRI scan can stay restricted to the region of the heart by using an alternative method to obtain the additional torso geometry required by ECGi.

A few previous studies evaluated the accuracy of the photography-based torso geometry reconstruction and ECG electrodes localization. Ghanem et al. [8] used stereo photography in a phantom study and was able to reconstruct electrode position within 1 mm of their actual location. This distance was within the diameter (5mm) of the ECG electrodes used for body surface mapping. Similarly, Schulze et al. used a phantom and reported comparable results [17]. Notably, our study was the first to evaluate agreement between two approaches in a real-world patient population, using the robust statistical Bland-Altman method. While average bias in electrode position in our study (0.1–2.5 mm) was well within the ECG electrode’s diameter (5mm), 95% limits of agreement exceeded 10 mm. Although previous studies showed that 10-mm errors in body surface ECG electrode position provide satisfactory ECGi results [18, 19], our results suggest that further work is needed to improve the accuracy of the body surface electrodes localization.

The mean vertical distance between electrodes in each strip was 15mm. However, the horizontal distance – distance between electrode strips- varied depending on the patient body morphology. This value ranged from 50 to 100mm. In addition, there can be a large error in positioning the strips a second time without previous knowledge of the first positioning of the electrode strips. Previous studies have shown the error in placing the electrodes with assistance of a previous 2D photography showing the electrode position [8]. Nevertheless, further improvement in the determination of the electrode location is needed for future use of this photographic method as a stand-alone technology.

A larger disagreement between MRI-based and 3D photography-based torso geometries was observed, as compared to the disagreement between CT-based and 3D photography-based torso geometries. The differences in the spatial resolution between MRI and CT in this study may have played a role in the level of agreement obtained with both methods. 3D photography demonstrated better agreement with the high-resolution imaging than with, low-resolution imaging. Therefore, if confirmed in the future prospective studies, 3D photography can become an important method for torso mesh generation and electrodes localization, as a substitution for low-resolution imaging of the chest.

As this is the first study testing and evaluating the accuracy of 3D photography technology for torso and electrode position reconstruction, both and inter- and intra- observer variability test was performed in this work. The results observed from both mesh reconstruction and electrode position suggest a substantial level of intra- and inter-observer agreement. This suggest that this semi-automated reconstruction method is relatively reproducible over multiple attempts and users.

Limitations

Several limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, the study size was relatively small. Nevertheless, we were able to observe important differences between the CT- based and MRI-based torso reconstruction subgroup’s agreement with the 3D photography-based torso reconstruction. A sufficient number of analyzed individual ECG electrodes (n=74) allowed careful assessment of agreement between two methods and was sufficiently powered. Second, only a subset of the body surface electrodes were localized using both approaches. Therefore, we were not able to assess differences in agreement of electrodes localization in different areas of the torso. However, importantly, we assessed agreement in ECG electrodes localization in the precordial area, which has the largest impact on ECGi accuracy and will be used in the future co-registration of the two different geometries (CT/MRI – based and 3D photography-based). A future study which includes the effects of geometrical factors, such as electrode position and mesh reconstruction, on the accuracy of BSP measurements and therefore epicardial maps through ECGi are needed to set the limits of accuracy of new emergent technology such as the 3D photography method in BSP and ECGi studies.

Conclusion

Torso geometry was successfully reconstructed, and ECG electrodes position on the surface of the body was correctly localized using the 3D photography technology. Substantial agreement in body surface ECG electrode coordinates and the torso geometries, as defined by the CT or MRI imaging and 3D photography, was observed. Further development of 3D photography - based technology of the torso geometry reconstruction and ECG electrode localization is needed.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Accurate torso geometry reconstruction using 3D photographic camera is feasible.

ECG electrodes coordinates obtained by CT/MRI and 3D photography, are in good agreement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by R01HL118277 (LGT).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ramanathan C, et al. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging for cardiac electrophysiology and arrhythmia. Nat.Med. 2004;10(4):422–428. doi: 10.1038/nm1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudy Y. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging of arrhythmogenic substrates in humans. Circ Res. 2013;112(5):863–74. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.279315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudy Y, Oster HS. The electrocardiographic inverse problem. Crit Rev.Biomed.Eng. 1992;20(1–2):25–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alday EA, et al. A new algorithm to diagnose atrial ectopic origin from multi lead ECG systems--insights from 3D virtual human atria and torso. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11(1):e1004026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berenfeld MSG, et al. Non-Invasive Localization of Maximal Frequency Sites of Atrial Fibrillation by Body Surface Potential Mapping. 2013 doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.112.000167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alday EA, et al. Comparison of Electric- and Magnetic-Cardiograms Produced by Myocardial Ischemia in Models of the Human Ventricle and Torso. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0160999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tereshchenko LG, et al. Electrical Dyssynchrony on Noninvasive Electrocardiographic Mapping correlates with SAI QRST on surface ECG. Comput Cardiol. 2010;42:69–72. 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghanem RN, et al. Heart-surface reconstruction and ECG electrodes localization using fluoroscopy, epipolar geometry and stereovision: application to noninvasive imaging of cardiac electrical activity. IEEE Trans.Med.Imaging. 2003;22(10):1307–1318. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.818263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Dam PM, Gordon JP, Laks M. Sensitivity of CIPS-computed PVC location to measurement errors in ECG electrode position: the need for the 3D camera. J Electrocardiol. 2014;47(6):788–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yushkevich PA, et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):1116–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huttenlocher DP, Klanderman GA, Rucklidge WJ. Comparing images using the Hausdorff distance. IEEE Transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence. 1993;15(9):850–863. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guthe M, Borodin P, Klein R. Fast and accurate Hausdorff distance calculation between meshes. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bland JM, Altman D. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. The lancet. 1986;327(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawrence I, Lin K. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics. 1989:255–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley EL, Blackwood LG. Comparing paired data: a simultaneous test for means and variances. American Statistician. 1989(43):234–235. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong Z, et al. Computational Depth Sensing : Toward high-performance commodity depth cameras. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine. 2017;34(3):55–68. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulze WH, et al. Automatic camera-based identification and 3-D reconstruction of electrode positions in electrocardiographic imaging. Biomed Tech (Berl) 2014;59(6):515–28. doi: 10.1515/bmt-2014-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burnes JE, et al. Noninvasive ECG imaging of electrophysiologically abnormal substrates in infarcted hearts : A model study. Circulation. 2000;101(5):533–540. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.5.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burnes JE, Taccardi B, Rudy Y. A noninvasive imaging modality for cardiac arrhythmias. Circulation. 2000;102(17):2152–2158. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.17.2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.