Decreasing unnecessary or inappropriate prescribing is a critical part of a multi-pronged approach to curb the morbidity associated with prescription opioids. Initial emphasis on opioid guidelines centered on the outpatient setting [1], but analgesics prescribed in the emergency department (ED) represent a substantial percentage of all opioid prescriptions [2–4]. Some patients will go on to prolonged opioid use [5, 6], and opioid use disorders have been documented as sequelae of opioids initiated for acute pain [7,8]. Limited studies have examined the impact of opioid prescribing policies implemented in the ED [9,10]; to our knowledge, none have examined whether policies differentially impact specific providers based on their prescribing patterns or type of training.

We performed an interrupted time-series analysis utilizing data obtained from the electronic health records (EHR) of a large health system in the year before and after implementation of an ED opioid prescribing policy (implementation date October 31, 2013), a set of guidelines intended to reduce inappropriate opioid prescribing in certain conditions. We examined three hospitals within the same state (1): an academic tertiary-care level 1 trauma center with >105,000 ED visits per year, an emergency medicine residency program, and many mid-level providers (Hospital 1) (2); a community hospital with ~65,000 ED visits per year (Hospital 2); and (3) a community hospital with ~30,000 ED visits per year (Control). The opioid prescribing policy was implemented only at Hospitals 1 and 2, but not the control hospital (30 miles away) to evaluate the potential for external factors influencing prescribing. The study was approved by the hospital system’s Institutional Review Board.

We limited our analysis to visits for the following ICD-9 codes: abdominal pain (789.X), dental pain (525.9) or caries (521.0); headache, including migraine (784.0, 346.1, 346.9, 307.81, 339.1X), back pain (724.X, 722.5X, 722.6) and chronic pain (338.29). We determined changes in the opioid prescribing in the year before and after the policy via comparison of the average number of opioid prescriptions, graphical representation, and segmented regression analysis (α = 0.008 with Bonferroni correction (n = 6)). Providers were stratified into levels of prescribing behavior (low, medium or high) based on tertiles of the proportion of visits in which patients were prescribed an opioid. Analyses were repeated, stratified by level of prescribing and by provider level.

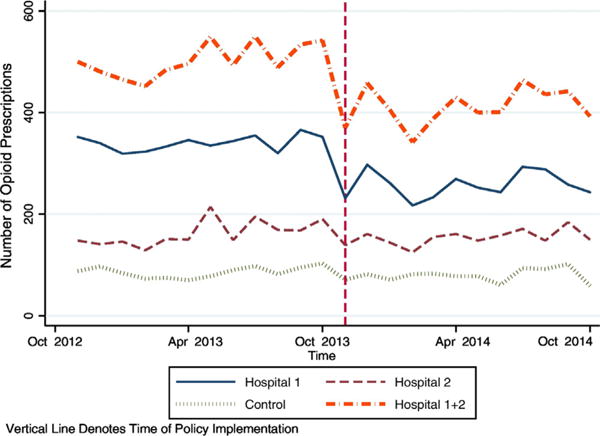

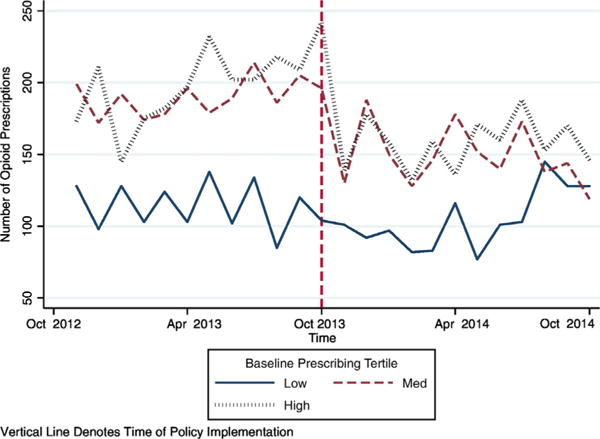

There were 18,777 and 21,845 patient visits (Hospitals 1 and 2) for the diagnoses of interest in the pre- and post-policy periods, respectively. Over the study period, opioid use in the ED and at discharge declined at all 3 sites (Table 1, Fig. 1), with Hospital 1 experiencing the greatest decrease. Providers with the highest levels of pre-policy prescribing had the largest reduction in prescribing (Fig. 2). This held true for sub-groups of providers as well; mid-level providers had the highest rate of prescribing at baseline (45% of all discharged patients received an opioid), but also the largest amount of change pre- and post-policy (−10%). In segmented regression analysis, the intervention hospitals prescribed significantly fewer opioids in the post-policy periods: 101 (95% CI: 67, 134, < 0.001), Hospital 1; 49 (95% CI: 21, 77, p < 0.001), Hospital 2; Control 20 (95% CI: 30, 1, p = 0.037) (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Opioids administered in the ED and prescribed at discharged, before and after implementation of an opioid prescribing policy at two intervention hospitals and a third control.

| Pre-policy period

|

Post-policy period

|

Difference (95% CI)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Visits with opioids administered in the EDa | |||||

| Hospital 1 | 7311 | 58.7 | 6350 | 52.1 | −6.6 (−7.8, −5.3) |

| Hospital 2 | 4536 | 56.3 | 4138 | 52.2 | −4.1 (−5.6, −2.6) |

| Hospitals 1 and 2 | 11,847 | 57.8 | 10,488 | 52.2 | −5.6 (−6.6, −4.6) |

| Control | 1601 | 57.4 | 1566 | 55.1 | −2.3 (−4.9, 3.3) |

| Hospitals 1 and 2 | |||||

| Baseline prescribing levelc | |||||

| Low | 3888 | 55.9 | 3673 | 51.4 | −4.5 (−6.2, −2.9) |

| Medium | 4257 | 57.6 | 3797 | 51.6 | −6.0 (−7.6, −4.4) |

| High | 3702 | 60.0 | 3018 | 53.8 | −6.1 (−7.9, −4.4) |

| Level of trainingd (midlevel) | |||||

| PA/NP | 3246 | 59.7 | 2710 | 51.0 | −8.7 (−10.6, −6.9) |

| PGY-1 | 409 | 52.9 | 143 | 50.5 | −2.4 (−9.2, 4.4) |

| PGY-2 | 622 | 56.9 | 567 | 48.8 | −8.0 (−12.1, −3.9) |

| PGY-3 | 726 | 59.0 | 805 | 51.8 | −7.2 (−10.9, −3.5) |

| PGY-4 | 1052 | 58.6 | 1332 | 56.7 | −1.8 (−4.9, 1.2) |

| Attending | 5792 | 56.9 | 4931 | 52.2 | −4.7 (−6.1, −3.3) |

| Opioids prescribed at dischargeb | |||||

| Hospital 1 | 4032 | 39.1 | 3066 | 30.6 | −8.5 (−9.8, −7.2) |

| Hospital 2 | 1924 | 28.8 | 1837 | 27.4 | −1.3 (−2.8, 0.2) |

| Hospitals 1 and 2 | 5956 | 35.0 | 4903 | 29.3 | −5.7 (−6.7, −4.7) |

| Control | 1030 | 40.5 | 956 | 36.5 | −4.0 (−6.6, −1.3) |

| Hospitals 1 and 2 | |||||

| Baseline prescribing levelc | |||||

| Low | 1342 | 23.8 | 1240 | 21.0 | −2.8 (−4.4, −1.3) |

| Medium | 2254 | 36.5 | 1771 | 28.9 | −7.6 (−9.2, −5.9) |

| High | 2360 | 45.4 | 1892 | 40.3 | −5.1 (−7.0, −3.1) |

| Level of trainingd | |||||

| PA/NP (midlevel) | 2114 | 45.2 | 1548 | 34.5 | −10.7 (−12.7, −8.7) |

| PGY-1 | 161 | 24.5 | 57 | 23.7 | −0.9 (−7.2, 5.4) |

| PGY-2 | 261 | 29.4 | 266 | 26.7 | −2.7 (−6.8, 1.3) |

| PGY-3 | 240 | 25.9 | 277 | 22.8 | −3.1 (−6.8, 0.6) |

| PGY-4 | 350 | 29.0 | 357 | 21.8 | −7.3 (−10.5, −4.1) |

| Attending | 2830 | 32.8 | 2398 | 30.0 | −3.2 (−4.6, −1.8) |

Proportion of total visits.

Proportion of discharges.

Tertile of prescribing based on pre-policy # of opioids prescribed at discharge.

Level of training: PA = Physician Assistant, NP = Nurse Practioner, PGY = post-graduate year (refers to year of residency).

Fig. 1.

Discharge opioid prescriptions over time, stratified by hospital (Hospitals 1 & 2 (intervention sites) versus control).

Fig. 2.

Discharge opioid prescriptions over time, stratified by providers baseline prescribing behavior (Hospitals 1 & 2 (intervention sites)).

Our analysis suggests that an ED-based policy may be effective in reducing opioid prescribing, in particular by impacting providers with the highest baseline prescribing. We noted that the mid-level providers – who were also the provider subgroup with the highest rate of prescribing in the pre-policy period had the largest amount of change pre- and post-policy. The pre- and post-differences were most pronounced at Hospital 1, the academic medical center. It may be teaching settings may be more dynamic in adopting latest best practices.

Over the pre- and post-policy period our control hospital also experienced modest declines in opioid prescribing. We postulate that this is unlikely to be an effect of the policy given its geographic distance and distinct staff; rather, opioid prescribing was likely influenced by factors such as media attention, department of health regulations, national guidelines, and continuing education.

A recent study suggested that provider prescribing variability was associated with transition to chronic opioid use after an ED visit: patients who saw a provider who prescribed opioids more often at discharge were more likely to continue use over the next year [5]. If true, this would argue for opioid prescribing guidelines to standardize emergency provider behavior.

Although there appear to be other unmeasurable changes impacting opioid prescribing, our results suggest a hospital system prescribing policy may reduce the amount of opioid prescriptions dispensed at hospital discharge, particularly among the high-prescribing ED providers. Providing clear guidelines across a range of common pain complaints, establishing low prescribing as a norm, and targeting high prescribers may be an effective vehicle for combatting the role of emergency care in opioid abuse, diversion, morbidity and mortality.

Contributor Information

Francesca L. Beaudoin, The Department of Emergency Medicine, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI, United States.

Adam Janicki, The Department of Emergency Medicine, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI, United States; The Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Pittsburg, Pittsburg, PA, United States.

Wanting Zhai, The Department of Biostatistics, Brown University, Providence, RI, United States.

Esther K. Choo, The Department of Emergency Medicine, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI, United States; The Department of Emergency Medicine, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, United States.

References

- 1.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1–49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volkow ND, McLellan TA, Cotto JH, Karithanom M, Weiss SR. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions in 2009. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1299–301. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoppe JA, Nelson LS, Perrone J, Weiner SG. Prescribing opioids safely in the emergency department study I, prescribing opioids safely in the emergency department PSI. Opioid prescribing in a cross section of US emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66(3):253–9 [e251]. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazer-Amirshahi M, Mullins PM, Rasooly I, van den Anker J, Pines JM. Rising opioid prescribing in adult U.S. emergency department visits: 2001–2010. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(3):236–43. doi: 10.1111/acem.12328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-prescribing patterns of emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):663–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1610524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoppe JA, Kim H, Heard K. Association of emergency department opioid initiation with recurrent opioid use. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(5):493–9 [e494]. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuehn BM. SAMHSA: pain medication abuse a common path to heroin: experts say this pattern likely driving heroin resurgence. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1433–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaudoin FL, Straube S, Lopez J, Mello MJ, Baird J. Prescription opioid misuse among ED patients discharged with opioids. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(6):580–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.del Portal DA, Healy ME, Satz WA, McNamara RM. Impact of an opioid prescribing guideline in the acute care setting. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(1):21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox TR, Li J, Stevens S, Tippie T. A performance improvement prescribing guideline reduces opioid prescriptions for emergency department dental pain patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(3):237–40. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]