Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the difference in tubal ligation use between rural and urban counties in the state of Georgia, USA.

Methods

The study population included 2,160 women aged 22–45. All participants completed a detailed interview on their reproductive histories. County of residence was categorized using the National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme. We estimated the association between urbanization of county of residence and tubal ligation using Cox regression. Among women with a tubal ligation, we examined factors associated with prior contraception use and the desire for more children.

Findings

After adjustment for covariates, women residing in rural counties had twice the incidence rate of tubal ligation compared with women in large metropolitan counties (adjusted Hazard Ratio (aHR) = 2.0, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = 1.4–2.9) and were on average 3 years younger at the time of the procedure. No differences were observed between small metropolitan and large metropolitan counties (aHR = 1.1, CI = 0.9–1.5). Our data trend to suggest that women from large metropolitan counties are slightly more likely than women from rural counties to use hormonal contraception or long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) prior to tubal ligation and to desire more children after tubal ligation.

Conclusions

Women from rural counties are more likely to undergo a tubal ligation than their urban counterparts. Our results suggest that circumstances regarding opting for tubal ligation may differ between urban and rural areas, and recommendations of alternative contraceptive options may need to be tailored differently for rural areas.

Keywords: access to care, epidemiology, health disparities, observational data, tubal ligation

Rural residents are at a health care disadvantage compared with their suburban and urban counterparts. Approximately 50 million Americans live in rural counties, which is about 20% of the United States population.1 However, only 9% of American physicians practice in these areas.2 In addition to a lower physician to patient ratio than their urban counterparts, rural residents also have poorer health outcomes and more risk factors for disease such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.1 There may also be a substantial rural-urban disparity in family planning and reproductive services with 55% fewer obstetrician-gynecologists (OB/GYN) in rural areas than in urban areas, and 10.1 million women living in a county without an OB/GYN.1, 3

Tubal ligation is the most common permanent contraceptive option available to women.4 An average of 640,000 procedures are performed each year in the United States, and it is the second most used form of contraception in the US and the most common among women over the age of 30.5, 6 Despite its effectiveness, tubal ligation may not always be the most appropriate option for some women. The permanency of this procedure can result in women having regret and pursuing invasive reversal procedures that may not be successful.4, 6, 7 Women who are sterilized at young ages are at the greatest risk for regret.7 Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) may offer significant advantages over tubal ligation, providing reversible options that offer highly effective birth control for up to 10 years.8 LARC usage has increased from 1.5% to 7.2% from 2002 to 2013 in the US.9 Increased usage and acceptance of LARC has coincided with a decrease in tubal ligation rates in Europe; however, this decrease has not been observed in the US.5 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advocates LARC as an appropriate alternative to tubal ligation for nearly all women, especially women who are under the age of 30, and it supports increased usage and availability of LARC.10

Cross-sectional studies have reported that the prevalence of tubal ligation in the US is greater in rural areas than in urban areas.11, 12 We expand on these findings by using a 3-tiered classification scheme to evaluate whether the rate of tubal ligation procedures differs across rural, small metropolitan, and large metropolitan areas in the state of Georgia. Further, we use survival analysis to assess whether age at tubal ligation differs between these groups. We also provide information on the use of alternative forms of contraception, in order to determine whether women’s contraception utilization before tubal ligation differs by geography. Finally, we explore whether desire for more children after tubal ligation (a proxy for regret) differs by geography.

Materials and Methods

This study uses data from the Furthering Understanding of Cancer, Health, and Survivorship in Adult (FUCHSIA) Women’s Study, a study of cancer survivors and women without a history of cancer residing in the state of Georgia. Cancer survivors were identified from the Georgia Cancer Registry and a comparison group of women was matched on age and geographic region. Data collection was performed in 2012–2013. Women were required to be between the ages of 22–45 years, have a working telephone number, and have the ability to complete an interview in English. Interested women consented orally before completing a computer-assisted telephone interview. The institutional review board of Emory University and the Georgia Department of Public Health approved the study.

The primary exposure for this analysis was rural versus small metropolitan versus large metropolitan county of residence at the time of interview. Counties were coded according to the 2006 National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Urban-Rural Classification Scheme. This scheme categorizes counties into levels of noncore, micropolitan, small metropolitan, medium metropolitan, large fringe metropolitan, and large central metropolitan areas with categories and definitions chosen specifically for their utility in studying health differences across the urban-rural continuum.13 For this study, noncore and micropolitan counties were classified as rural, small and medium metropolitan were classified as small metropolitan, and large fringe and large central metropolitan were classified as large metropolitan.

During the interview women were asked whether they had a procedure to tie or block, but not remove their fallopian tubes. This question was designed to capture the most common forms of postpartum and interval tubal ligation, including hysteroscopic tubal inserts. Women who reported having this procedure were then asked at what age and why they had the procedure. Only women who reported having a tubal ligation to prevent pregnancy were classified as having a tubal ligation for analyses.

The interview also collected information on a number of covariates including hysterectomy, oophorectomy, birth control methods used, income, education, insurance status, relationship history, pregnancy history, and desire for future children. Pregnancy history was used to determine gravidity, parity, and whether each pregnancy was unintended. Pregnancies were classified as unintended if a woman was on birth control at the time of conception or if she indicated she was not trying to get pregnant at that time. Reported birth control methods were used to create indicators of ever use of hormonal contraception or long-acting reversible contraception, defined as progestin implants and intrauterine devices (IUD). For our analyses, hormonal contraception included: the combined oral contraceptive, contraceptive patch, vaginal ring, and the progestin only pill and injection. Insurance status was categorized as employer-based, self-insured, public (which included Medicaid, Medicare, and military insurance), or none.

We used SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) for statistical analyses and R 3.0.1 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) for graphics. Covariates were summarized using counts and percentages and compared across urbanicity categorizations and tubal ligation status using chi-square tests and unadjusted odds ratios. We fit Cox proportional hazards regression using age as the time scale to determine if differences in the rate of tubal ligations existed between rural and urban women, using generalized estimating equations to account for clustering of women within counties. Time of the event was defined as the age of tubal ligation. Women who had a tubal ligation for reasons other than to prevent pregnancy were censored at the age of their tubal ligation (n = 21). For analysis, women who did not have a tubal ligation at the age of their hysterectomy, oophorectomy, or interview were considered no longer at risk of having a tubal ligation and were censored at this age in our survival analysis. Potential confounders included race, prior use of hormonal contraception, prior use of LARC, household income, current insurance status, education, parity, history of unintended pregnancy, and history of cancer. We compared the estimated effects of residence in the fully adjusted model (ie, including all covariates) to the estimates in models dropping one covariate at a time. Race and education were retained in the model because of their established associations with both place of residence and tubal ligation. For other covariates, those whose removal changed the estimates by less than 10% were excluded from the final model. The main model included cancer survivors and women without a history of cancer, but additional models were fit stratifying on cancer status.

We performed a subanalysis of the women who had a tubal ligation to determine the factors associated with not using any form of hormonal contraception or LARC before having a tubal ligation. Predictors assessed in bivariate analysis included degree of urbanization of resident county, race, history of unintended pregnancy, parity, current type of health insurance, household income, current insurance status, education, and marital status at the time of tubal ligation. Women who had a tubal ligation but desired future children at the time of the interview were classified as having not met their reproductive goals as a proxy for regret. We looked at the factors that might be associated with women desiring more children in a bivariate analysis that included degree of urbanization of resident county, race, age at tubal ligation, education, household income, and time between last pregnancy and tubal ligation. We used a proxy of tubal ligation performed within the same year as the final pregnancy as an estimate of post-partum tubal ligation.14 Multivariable analyses were not performed because of small numbers.

Results

Of 2636 women interviewed, 265 were excluded because they did not provide information on incidence of tubal ligation (7 refused to answer, 258 did not complete interview), and 211 were excluded because they did not provide a county of residence (n = 2) or lived outside the state of Georgia (n = 209). The proportion of women with missing incidence of tubal ligation did not differ by urban-rural status (rural: 8%, small metropolitan: 9%, large metropolitan: 10%, P = .78). After exclusions, 2160 women were eligible for analysis with 1548 residing in large metropolitan counties, 372 in small metropolitan counties, and 240 in rural counties (Table 1). In our study population, 12% of women had a tubal ligation performed to prevent pregnancy, at an average age of 30 years. Women from rural counties were more likely to have undergone a tubal ligation: 20% of rural participants had a tubal ligation compared with 13% of small metropolitan women and 10% of large metropolitan women (P < .001). Rural women were more likely to be non-Hispanic white, have less education, have lower household income, and have more children than women from large and small metropolitan counties. Women from rural and small metropolitan counties were also found to have their first child at a younger age. Women from small metropolitan counties were the most likely to have had an unintended pregnancy and to be on public health insurance. There were no substantial differences between urban and rural women with respect to their current age, LARC or hormonal contraception usage, or relationship status.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Women 22–45 in Georgia From the FUCHSIA Women’s Study by Metropolitan County Status Defined by the NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme (N = 2160).

| Large Metropolitan |

Small Metropolitan |

Rural | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 1548) | (N = 372) | (N = 240) | ||

| Tubal Ligation | ||||

| Yes | 153 (9.9%) | 49 (13.2%) | 48 (20.0%) | < .001 |

| No | 1395 (90.1%) | 323 (86.8%) | 192 (80.0%) | |

| Cancer Survivor | ||||

| Yes | 760 (49.1%) | 205 (55.1%) | 120 (50.0%) | .114 |

| No | 788 (50.9%) | 167 (44.9%) | 120 (50.0%) | |

| Current Age | ||||

| 22–29 | 87 (5.6%) | 31 (8.3%) | 20 (8.3%) | |

| 30–39 | 845 (54.6%) | 192 (51.6%) | 133 (55.4%) | .176 |

| 40–45 | 616 (39.8%) | 149 (40.1%) | 87 (36.3%) | |

| Age at tubal ligationa | ||||

| 22–29 | 63 (41.2%) | 28 (57.1%) | 23 (47.9%) | |

| 30–39 | 82 (53.6%) | 20 (40.8%) | 24 (50.0%) | .336b |

| 40–45 | 8 (5.2%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1 (2.1%) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 951 (61.5%) | 246 (66.3%) | 193 (80.4%) | <.001 |

| Black | 470 (30.4%) | 100 (27.2%) | 38 (15.8%) | |

| Hispanic | 64 (4.1%) | 6 (1.6%) | 2 (0.8%) | |

| Other | 63 (3.9%) | 20 (4.9%) | 7 (2.9%) | |

| Type of Contraception Use | ||||

| Hormonal Contraceptionc | 1245 (80.4%) | 282 (75.8%) | 182 (75.8%) | .060 |

| LARCd | 283 (18.3%) | 59 (15.9%) | 40 (16.7%) | .497 |

| Neither | 262 (16.9%) | 81 (21.8%) | 51 (13.7%) | .041 |

| History of Unintended Pregnancy | ||||

| No | 804 (51.9%) | 161 (43.4%) | 114 (47.5%) | .081 |

| One | 340 (22.0%) | 93 (25.0%) | 64 (26.7%) | |

| Two | 202 (13.0%) | 59 (15.9%) | 31 (12.9%) | |

| ≥ Three | 202 (13.0%) | 59 (15.9%) | 31 (12.9%) | |

| Paritye | ||||

| Zero | 415 (26.8%) | 69 (18.6%) | 43 (17.9%) | .005 |

| One | 305 (19.7%) | 78 (21.0%) | 52 (21.7%) | |

| Two | 532 (34.4%) | 146 (39.2%) | 87 (36.1%) | |

| ≥ Three | 295 (19.1%) | 79 (21.2%) | 58 (24.2%) | |

| Age at first child, mean (SD) | 26.3 (5.4) | 24.4 (5.3) | 23.9 (5.1) | < .001 |

| Type of Health Insurancef | ||||

| Employerg | 1197 (78.0%) | 232 (62.5%) | 162 (68.1%) | < .001 |

| Self | 96 (6.3%) | 13 (3.5%) | 10 (4.2%) | |

| Publich | 107 (7.0%) | 70 (18.9%) | 27 (11.3%) | |

| None | 135 (8.8%) | 56 (15.1%) | 39 (16.4%) | |

| Incomei | ||||

| < 25K | 159 (10.6%) | 78 (21.4%) | 55 (23.5%) | < .001 |

| 25K – 49K | 260 (17.3%) | 77 (21.2%) | 50 (21.4%) | |

| 50K – 74K | 262 (17.4%) | 69 (19.0%) | 52 (22.2%) | |

| 75K – 100K | 285 (18.9%) | 66 (18.1%) | 38 (16.2%) | |

| > 100K | 539 (35.8%) | 74 (20.3%) | 39 (16.7%) | |

| Educationj | ||||

| High School or Less | 82 (5.3%) | 37 (10.0%) | 27 (11.2%) | < .001 |

| Some College | 357 (23.1%) | 124 (33.3%) | 85 (35.4%) | |

| College Graduate | 580 (37.5%) | 114 (30.6%) | 74 (30.1%) | |

| Graduate School | 527 (34.1%) | 97 (26.1%) | 54 (22.5%) | |

| Desire more childrenk | ||||

| No | 768 (50.0%) | 203 (55.0%) | 126 (53.2%) | .211 |

| Yes | 762 (50.0%) | 166 (45.0%) | 111 (46.8%) | |

| Marital Status at Event | ||||

| Married or Living Together | 1160 (74.9%) | 288 (77.4%) | 187 (77.9%) | .421 |

| Other | 388 (25.1%) | 84 (22.6%) | 53 (22.1%) | |

Percentages are calculated among those that had a tubal ligation

Fisher’s exact test used

Includes the birth control pill, birth control patch, Nuvaring, the mini-Pill, and Depo Provera

Includes Norplant, Implanon, hormone releasing IUD, and non-hormone releasing IUD

Missing data for 1 large metropolitan woman

Missing data for 13 large metropolitan, 1 small metropolitan, and 2 rural women

Includes own employer insurance, partner’s employer insurance, or parents insurance

Includes Medicaid, Medicare, and military insurance

Missing data for 43 large metropolitan, 8 small metropolitan, and 6 rural women

Missing data for 2 large metropolitan women

Missing data for 18 large metropolitan, 3 small metropolitan, and 3 rural women

Table 2 shows bivariate relationships with tubal ligation status. The unadjusted odds of having a tubal ligation performed were 1.4 times greater in black women compared to white women (95% CI = 1.1–1.9). Women who previously used LARC (OR = 0.6, 95% CI = 0.4–0.9) or hormonal contraceptives (OR = 0.7, 95% CI = 0.5–0.9) were less likely to have a tubal ligation. Women with public or no insurance, and women who had no college degree were more likely to have had a tubal ligation. Of women who had a tubal ligation, 44% had this performed within 1 year of their final pregnancy (data not shown). This proportion differed by urban-rural status (rural: 54%, small metropolitan: 59%, large metropolitan: 36%, P = .004).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Women 22–45 Living in Georgia From the FUCHSIA Women’s Study by Tubal Ligation Status (N = 2160).a

| Tubal Ligation | No Tubal Ligation | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 250) | (N = 1910) | |||

| Location | ||||

| Large Metro | 153 (9.9%) | 1395 (90.1%) | Reference | |

| Small Metro | 49 (13.2%) | 323 (86.8%) | 1.4 | 1.0–2.0 |

| Rural | 48 (20.0%) | 192 (80.0%) | 2.3 | 1.6–3.3 |

| Cancer Survivor | ||||

| Yes | 111 (10.2%) | 974 (89.8%) | 1.3 | 1.0–1.7 |

| No | 139 (12.9%) | 936 (87.1%) | Reference | |

| Current Age | ||||

| 22–29 | 7 (5.1%) | 131 (94.9%) | 0.5 | 0.2–1.1 |

| 30–39 | 125 (10.7%) | 1045 (89.3%) | Reference | |

| 40–45 | 139 (16.3%) | 713 (83.7%) | 1.7 | 1.3–2.2 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 141 (10.1%) | 1249 (89.9%) | Reference | |

| Black | 85 (14.0%) | 523 (86.0%) | 1.4 | 1.1–1.9 |

| Hispanic | 12 (16.7%) | 60 (83.3%) | 1.7 | 0.9–3.4 |

| Other | 12 (13.2%) | 78 (86.8%) | 1.4 | 0.7–2.6 |

| Type of Contraceptive Use | ||||

| Hormonal Contraceptionb, c | 183 (10.7%) | 1526 (89.3%) | 0.7 | 0.5–0.9 |

| LARCd, e | 29 (7.6%) | 353 (92.4%) | 0.6 | 0.4–0.9 |

| Neitherf | 63 (16.0%) | 331 (84.0%) | 1.6 | 1.2–2.2 |

| History of Unintended Pregnancy | ||||

| No | 51 (4.7%) | 1028 (95.3%) | Reference | |

| One | 79 (15.9%) | 418 (84.1%) | 3.8 | 2.6–5.5 |

| Two | 51 (17.5%) | 241 (82.5%) | 4.3 | 2.8–6.4 |

| ≥ Three | 69 (23.6%) | 223 (76.4%) | 6.2 | 4.2–9.2 |

| Parityg | ||||

| Zero | 3 (0.6%) | 524 (99.4%) | 0.1 | 0.0–0.5 |

| One | 17 (3.9%) | 418 (96.1%) | Reference | |

| Two | 124 (16.2%) | 641 (83.8%) | 4.8 | 2.8–8.0 |

| ≥ Three | 105 (24.3%) | 327 (75.7%) | 7.9 | 4.6–13.5 |

| Type of Health Insuranceh | ||||

| Employeri | 165 (10.4%) | 1426 (89.6%) | Reference | |

| Self | 10 (8.4%) | 109 (91.6%) | 0.8 | 0.4–1.5 |

| Publicj | 32 (15.7%) | 172 (84.3%) | 1.6 | 1.1–2.4 |

| None | 42 (18.3%) | 188 (81.7%) | 1.9 | 1.3–2.8 |

| Incomek | ||||

| < 25K | 41 (14.0%) | 251 (86.0%) | 0.9 | 0.6–1.4 |

| 25K – 49K | 46 (11.9%) | 341 (88.1%) | 0.7 | 0.5–1.1 |

| 50K – 74K | 59 (15.4%) | 324 (84.6%) | Reference | |

| 75K – 100K | 43 (11.1%) | 346 (88.9%) | 0.7 | 0.4–1.0 |

| > 100K | 56 (8.6%) | 596 (91.4%) | 0.5 | 0.3–0.8 |

| Educationl | ||||

| High School or Less | 33 (22.6%) | 113 (77.4%) | 1.5 | 1.0–2.4 |

| Some College | 90 (15.9%) | 476 (84.1%) | Reference | |

| College Graduate | 61 (7.9%) | 707 (92.1%) | 0.5 | 0.3–0.6 |

| Graduate School | 66 (9.7%) | 612 (90.3%) | 0.6 | 0.4–0.8 |

| Met Reproductive Goalsm | ||||

| Yes | 196 (17.9%) | 901 (82.1%) | 4.1 | 3.0–5.7 |

| No | 52 (5.0%) | 987 (95.0%) | Reference | |

| Marital Status at Event | ||||

| Married or Living Together | 208 (12.7%) | 1427 (87.3%) | 1.7 | 1.2–2.4 |

| Other | 42 (8.0%) | 483 (92.0%) | Reference | |

Row percents shown

Includes the birth control pill, birth control patch, Nuvaring, the mini-Pill, and Depo Provera

Reference group is no ever hormonal contraception use

Includes Norplant, Implanon, hormone releasing IUD, and non-hormone releasing IUD

Reference group is no ever LARC use

Reference group is ever LARC or hormonal contraception use

1 tubal ligation missing

1 tubal ligation and 15 no tubal ligation missing

Includes own employer insurance, partner’s employer insurance, or parents insurance

Includes Medicaid, Medicare, and military insurance

5 tubal ligation and 52 no tubal ligation missing

2 no tubal ligation missing

2 tubal ligation and 22 no tubal ligation missing

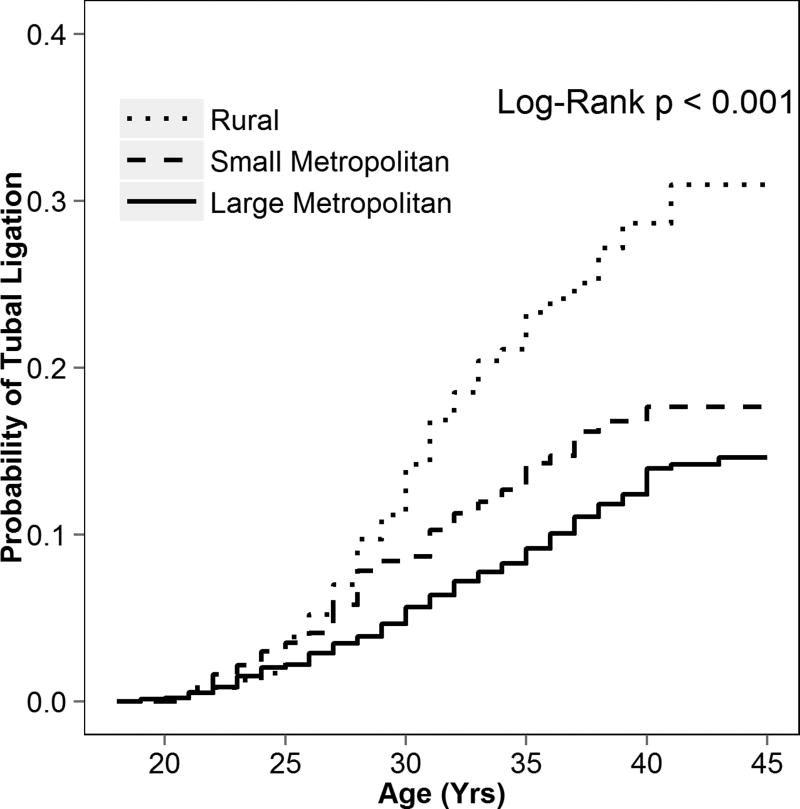

Women in rural areas had tubal ligations more often at younger ages than women in small metropolitan and large metropolitan areas (Figure 1). Based on unadjusted Kaplan-Meier plots, at age 30, 14% of rural women, 8% of small metropolitan women, and 5% of large metropolitan women had a tubal ligation. At the oldest observed age (45 years), approximately 30% of rural women, 17% of small metropolitan women, and 13% of large metropolitan women had a tubal ligation. The unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) for tubal ligation was 2.5 (95% CI = 1.7–3.5) comparing women living in rural counties with women from large metropolitan counties. The unadjusted HR for tubal ligation was also elevated (HR = 1.5, 95% CI = 1.0–2.0) for women from small metropolitan counties compared with those from large metropolitan counties (Table 3). After adjustment for race, education, household income, insurance type, and parity, the effect estimate for rural versus large metropolitan counties remained elevated (HR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.4–2.9), but the estimate for small versus large metropolitan counties moved towards the null (HR = 1.1, 95% CI = 0.9–1.5). Excluding cancer survivors did not change the results [rural HR = 2.0 (95% CI = 1.2–3.1), small metropolitan HR = 1.2 (95% CI = 0.8–1.8)].

Figure 1.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier Survival Curve of Tubal Ligations in Women 22–45 in Georgia From the FUCHSIA Women’s Study by County Metropolitan Status Defined by the 2006 National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Categorization Scheme (N = 2153).

Table 3.

Crude and Multivariable Cox Regression Analysis of the Effect of Metropolitan County Status Defined by the NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme on the Incidence of Tubal Ligation Among Women 22–45 in the FUCHSIA Women’s Study (N = 2160).

| Geographic Area | N | No. of | Unadjusted* | Adjusteda, b, c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tubal Ligations | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||

| Large Metropolitan | 1500 | 153 | 1.0 | Reference | 1.0 | Reference |

| Small Metropolitan | 363 | 49 | 1.4 | 1.0–2.0 | 1.1 | 0.9–1.5 |

| Rural | 233 | 48 | 2.5 | 1.7–3.5 | 2.0 | 1.4–2.9 |

HR, Hazard Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval

Clustering within counties accounted for using robust standard errors

63 observations excluded because of missing covariates

Adjusted for race, education, household income, type of insurance, and parity

Among women who had a tubal ligation (N = 250), there was a suggestion that rural women were slightly more likely than women from large metropolitan counties to have never used hormonal contraception or LARC before having a tubal ligation, but the results were not significant (OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 0.7–2.9). Young age at tubal ligation (< 25 years), non-white race, history of unintended pregnancy, higher parity, no health insurance, low income, and low education were predictors of no hormonal contraception or LARC use prior to tubal ligation (data not shown). In particular, the odds of not using hormonal contraception or LARC before tubal ligation in women with household income below $50,000 was 2.9 times greater (95% CI = 1.6–5.2) than in women with over $50,000 income. The OR comparing women with no health insurance to women with employer-based health insurance was 2.7 (95% CI = 1.3–5.5), and black women had 2.2 times the odds of no prior hormonal contraception or LARC use (95% CI = 1.2–4.0) compared with white women.

Table 4 shows bivariate relationships between various predictors and the probability of women desiring more children at the time of the interview among women who had a tubal ligation. Though these data were non-significant, they are trending to suggest that rural women are slightly less likely to desire more children after tubal ligation compared with women from large metropolitan counties, after adjusting for current age, race, age at tubal ligation, income, and education (OR = 0.5, 95% CI = 0.2–1.2). A similar non-significant association was seen between women from small versus large metropolitan counties after multivariable modeling (OR = 0.6, 95% CI = 0.2–1.4). Women who desired more children at the time of the interview were on average 3 years younger at tubal ligation than women who did not desire more children. Women were significantly more likely to desire more children if they had a lower income (<$50, 000) or had a longer time (> 15 years) since their tubal ligation. Elevated, but non-significant odds of desiring more children were observed for black race, lower education, and having a tubal ligation within one year of their last pregnancy.

Table 4.

Bivariate Associations Between Demographic Characteristics and Failure to Meet Reproductive Goals Among Women 22–45 Who Have Had a Tubal Ligation in the FUCHSIA Women’s Study (N = 247).a

| Desire More Children |

Desire No More Children |

OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 52) | (N = 195) | |||

| Residence | ||||

| Large Metropolitan | 35 (23.0%) | 117 (77.0%) | Reference | |

| Small Metropolitan | 9 (18.4%) | 40 (81.6%) | 0.7 | 0.3–1.7 |

| Rural | 8 (17.0%) | 39 (83.0%) | 0.7 | 0.3–1.6 |

| Average Age at Tubal Ligationb | 27.5 (5.2) | 30.9 (4.9) | - | - |

| Race | ||||

| White | 26 (18.6%) | 114 (81.4%) | Reference | |

| Black | 21 (25.0%) | 63 (75.0%) | 1.5 | 0.8–2.8 |

| Education | ||||

| High School or Less | 33 (27.3%) | 88 (72.7%) | 1.7 | 0.8–3.7 |

| College Graduate | 11 (18.0%) | 50 (82.0%) | Reference | |

| Graduate School | 8 (12.1%) | 58 (87.9%) | 0.6 | 0.2–1.7 |

| Incomec | ||||

| < 50K | 26 (30.6%) | 59 (69.4%) | 2.3 | 1.3–4.4 |

| ≥ 50K | 25 (15.8%) | 133 (84.2%) | Reference | |

| Parityd | ||||

| Zero or One | 8 (40.0%) | 12 (60.0%) | 2.8 | 1.0–7.5 |

| Two | 24 (19.5%) | 99 (80.5%) | Reference | |

| ≥ Three | 19 (18.5%) | 84 (81.6%) | 0.9 | 0.5–1.8 |

| Time between Last Pregnancy and Tubal Ligation | ||||

| 0 years | 25 (23.2%) | 83 (76.9%) | 1.4 | 0.6–3.4 |

| 1 year | 19 (20.2%) | 75 (79.8%) | 1.2 | 0.5–2.9 |

| 2 or more years | 8 (17.8%) | 37 (82.2%) | Reference | |

| Time since Tubal Ligation | ||||

| 0 – 4 years | 10 (13.5%) | 64 (86.5%) | Reference | |

| 4 – 9 years | 9 (13.8%) | 56 (86.2%) | 1.0 | 0.4–2.8 |

| 10 – 14 years | 14 (21.5%) | 51 (78.5%) | 1.8 | 0.7–4.4 |

| 15 or more years | 19 (44.2%) | 24 (55.8%) | 5.0 | 2.1–12.7 |

Row Percents Shown

Mean and Standard Deviation Shown

Missing data for 1 woman who desires more children, 4 women who desire no more children

Missing data for 1 woman who desires more children

Discussion

Our study found that women from rural counties of Georgia had increased utilization of tubal ligation versus women from large metropolitan counties, after adjustment for demographic and socioeconomic factors. However, we did not observe any difference in utilization for women from small versus large metropolitan counties, suggesting these settings are more similar after accounting for differences in population characteristics. This suggests that circumstances regarding opting for tubal ligations in rural counties may not be the same as those in small and large metropolitan counties.

Twice as many of our rural women had a tubal ligation compared with women from large metropolitan areas, consistent with previous findings.11, 12 Unlike prior studies, we were able to separate large and small metropolitan counties. A slightly greater proportion of women from small metropolitan counties had tubal ligations compared with women from large metropolitan counties. However, after adjusting for confounders, women from small metropolitan counties were more similar to women from large metropolitan counties than to rural women. In contrast, rural women continued to be twice as likely to have a tubal ligation compared with women from large metropolitan counties after adjustment for potential confounders. This association did not differ between cancer survivors and cancer-free women, and therefore these groups were combined to improve precision of the estimate. Although insurance coverage and income differ between rural and urban women and also differ across women with and without a tubal ligation, adjustment for these variables did not change the results, suggesting additional factors contribute to the difference.

Ever use of either LARC or hormonal contraception was less likely among women who had a tubal ligation compared to women who did not have a tubal ligation. However, we found that our overall cohort of rural women had similar rates of contraception use to urban women. Among women who had undergone a tubal ligation, our data suggest that rural women may be less likely to have used LARC or hormonal contraception prior to a tubal ligation, but our sample size did not allow us to detect effect sizes of this magnitude or adjust for potential confounding. This should be investigated further in future studies.

We had postulated that the availability of physicians, specifically obstetric/gynecologic (OB/GYN) practices and family planning clinics, in rural areas may discourage or prevent rural women disproportionately from choosing reversible contraceptive options over tubal ligation. Instead, use of LARC or hormonal contraception seems to be more strongly associated with income or insurance status than with urbanization. Prior to the enactment of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), sterilization was more commonly covered by insurance plans than other forms of contraception.15 Given that most tubal ligations in our cohort were performed prior to the ACA, tubal ligations may have been the most feasible choice given a woman’s insurance policy. Both ACOG and The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that LARC be the first-line method of contraception offered to most women as a reversible alternative with comparable effectiveness to tubal ligation.8, 16 Our results suggest a possible need for increased access to reversible contraception, and specifically to LARC, for all women in Georgia contemplating tubal ligation. Future studies should be performed to assess how policy changes in health care coverage affect contraceptive utilization in rural areas and the differences compared to urban areas.

Our results suggest that rural women are not only having more tubal ligations performed, but that they are also more likely to have these procedures performed at younger ages. Regret is a common occurrence after tubal ligations and younger age at tubal ligation is associated with an increased likelihood to express regret.4, 6, 7 Using desire for children after tubal ligation as a proxy indicator of regret, our results showed a sizeable (21%) incidence of regret with women who desired more children tending on average to be younger at tubal ligation than women who did not (27.5 vs 30.9). Our results also suggest women from urban areas may be more likely to desire more children after tubal ligation, but this association may have occurred by chance. In many cases, women may prefer tubal ligation because it offers them a permanent option after they have completed child bearing. The fact that women who have met their desired family size were more likely to have a tubal ligation within a year from their last pregnancy provides some support for this possibility. With proper counseling and understanding of the permanency of tubal ligations, tubal ligations may be the most appropriate form of contraception for women who have completed child bearing.

A major strength of this study is the inclusion of age at procedure. The use of survival analysis allowed us to determine if women are undergoing tubal ligations at different ages in urban versus rural environments. Age at tubal ligation is important because age is typically associated with prevalence of regret after tubal ligation.7 Another strength is that our data come from a population-based study, which included information on a number of demographic characteristics, other forms of contraception used, and other reproductive surgeries. This allowed us to censor individuals when tubal ligation was no longer relevant (eg, after a hysterectomy). We also had an indirect indicator of current regret after tubal ligation, which allowed us to assess the differences in regret in rural versus urban environments. In addition, we are the first study to break down urban residence into large metropolitan or small metropolitan. Women from small metropolitan areas in our study were different from both women living in large metropolitan areas and rural women, and we were able to assess the differences in tubal ligation rate between these areas.

The primary limitation of our study is the use of current county of residence instead of residence at the time of tubal ligation. We assumed that the classification of a woman’s current county residence was the same as the classification of her residence at the time of tubal ligation. However, some women may have had their tubal ligation in a rural county prior to moving to an urban county and therefore were misclassified. This misclassification could result in a bias towards the null, whereas movement from an urban area to a rural area would likely lead to bias away from the null. From 2000 to 2010, the urban population in Georgia increased from 71.6% to 75.1%, which may suggest a bias towards the null is more likely.17 We were also unable to look specifically at post-partum tubal ligations as respondents were asked the age of their tubal ligation, but not the specific date or if their tubal ligation was performed post-partum. Because regret has been found to be similar for tubal ligation when performed within one year of the last pregnancy and when performed postpartum, we used a proxy of tubal ligation performed within the same year as their final pregnancy as an estimate of post-partum tubal ligations.14

Our results may not be generalizable to rural versus urban differences outside of Georgia, particularly areas of the country with populations with different demographic characteristics. However, our results may be generalizable to other southern states. Nevertheless, with 12% of our study population having undergone a tubal ligation, our estimate is lower than the national average of 16.5% reported by Jones and associates.18 However, as lower income is associated with a higher prevalence of tubal ligations18, the lower prevalence of tubal ligations in our study population may be attributable to the relatively high household income in our population. Assuming an average household size of 4, nearly 50% of our study population was living above 300% poverty level. In contrast, Jones and associates evaluated a population with 38% of participants living above 300% poverty level.18

In summary, we found that rural women are more likely to have a tubal ligation performed and have these procedures performed at younger ages than their large and small metropolitan counterparts. There was no difference in tubal ligation rates between women from small and large metropolitan counties after adjusting for confounders. Our data are trending to suggest that rural women are slightly less likely to have used hormonal contraception or LARC before their tubal ligation, but they are also slightly less likely to desire more children after tubal ligation. Given this pattern, tubal ligation may be the most feasible and appropriate form of contraception for some women in rural counties. Yet, it is not clear whether the difference observed between rural and urban tubal ligation incidence truly reflects differences in preferences of patients or other factors. Future studies should evaluate rural patients’ contraceptive decision-making and providers’ counseling practices before tubal ligation to assure that all women are aware of the alternatives to tubal ligation and have appropriate knowledge of contraception options.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Amy Fothergill for her support on the manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by NICHD grant 1R01HD066059 to Dr. Penelope P. Howards.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.United Health Center for Health Reform & Modernization. Modernizing Rural Health Care: Coverage, quality, and innovation. Minnetonka, Minnesota: United Health Center for Health Reform & Modernization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Dis J. MSJAMA. Where we live: health care in rural vs urban America. Jama. 2002 Jan;287(1):108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. [Accessed 01/24/2014];socioeconomic survey of ACOG fellows. 2008 :384–388. Available at http://www.acog.org/departments/dept_notice.cfm?recno=19&bulletin=5099.

- 4.Peterson HB. Sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jan;111(1):189–203. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000298621.98372.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan LM, Westhoff CL. Tubal sterilization trends in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010 Jun;94(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zite N, Borrero S. Female sterilisation in the United States. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2011 Oct;16(5):336–340. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2011.604451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis KM, Mohllajee AP, Peterson HB. Regret following female sterilization at a young age: a systematic review. Contraception. 2006 Feb;73(2):205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: Implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jul;118(1):184–196. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318227f05e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branum AM, Jones J. NCHS data brief, no 188. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. Trends in long-acting reversible contraception use among U.S. women aged 15–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 450: Increasing use of contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Dec;114(6):1434–1438. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c6f965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tobar A, Lutfiyya MN, Mabasa Y, et al. Comparison of contraceptive choices of rural and urban US adults aged 18–55 years: an analysis of 2004 behavioral risk factor surveillance survey data. Rural Remote Health. 2009 Jul-Sep;9(3):1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lunde B, Rankin K, Harwood B, Chavez N. Sterilization of Rural and Urban Women in the United States. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;122(2, PART 1):304–311. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31829b5a11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingram DD, Franco SJ. NCHS urban-rural classification scheme for counties. Vital Health Stat 2. 2012 Jan;(154):1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Tylor LR, Peterson HB. Poststerilization regret: findings from the United States Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:889–95. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00539-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonfield A, Gold RB, Frost JJ, Darroch JEUS. insurance coverage of contraceptives and the impact of contraceptive coverage mandates, 2002. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004 Mar-Apr;36(2):72–79. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.72.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2013. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Census Bureau. 2010 Census of Population and Housing, Population and Housing Unit Counts, CPH-2-12. Georgia U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones JMW, Daniels K. Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006–2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995. National Health Statistics Report. 2012;60:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]