Abstract

AIM

To summarise the current literature and define patterns of disease in migrant and racial groups.

METHODS

A structured key word search in Ovid Medline and EMBASE was undertaken in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. Studies on incidence, prevalence and disease phenotype of migrants and races compared with indigenous groups were eligible for inclusion.

RESULTS

Thirty-three studies met the inclusion criteria. Individual studies showed significant differences in incidence, prevalence and disease phenotype between migrants or race and indigenous groups. Pooled analysis could only be undertaken for incidence studies on South Asians where there was significant heterogeneity between the studies [95% for ulcerative colitis (UC), 83% for Crohn’s disease (CD)]. The difference between incidence rates was not significant with a rate ratio South Asian: Caucasian of 0.78 (95%CI: 0.22-2.78) for CD and 1.39 (95%CI: 0.84-2.32) for UC. South Asians showed consistently higher incidence and more extensive UC than the indigenous population in five countries. A similar pattern was observed for Hispanics in the United States. Bangladeshis and African Americans showed an increased risk of CD with perianal disease.

CONCLUSION

This review suggests that migration and race influence the risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease. This may be due to different inherent responses upon exposure to an environmental trigger in the adopted country. Further prospective studies on homogenous migrant populations are needed to validate these observations, with a parallel arm for in-depth investigation of putative drivers.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Ethnicity, Migration

Core tip: We reviewed the literature on the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in migrants and racial groups. Thirty-three studies met the inclusion criteria. Individual studies showed significant differences in incidence, prevalence and disease phenotype between migrants or race and indigenous groups. Only the incidence studies were sufficient in number and comparable for pooled analysis and meta-analysis. There was a trend for higher incidence for ulcerative colitis and lower incidence for Crohn’s disease in South Asian migrants. This review suggests that migration and race influence the risk of developing IBD. This may be due to different inherent responses upon exposure to an environmental trigger in the adopted country.

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are chronic inflammatory bowel conditions, collectively known as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the cause of which is unknown. An exaggerated immune response to antigenic stimulation by the gut microbiota on a background of genetic susceptibility is thought to drive the inflammatory process[1].

Epidemiologic studies suggest an increasing incidence and prevalence of IBD in developed countries[2]. Although there are fewer epidemiological data from developing countries, there appears to be a similar trend, fuelling its emergence as a global disease[3,4]. Some studies reported on a change in migrants moving from developing low incidence countries to developed high incidence countries, whereby they exhibit the incidence of the adopted country[5,6]. This phenomenon is worth exploring further for several reasons. Firstly, it implies there may be an environmental trigger for the disease as the onset is too rapid to be accounted for by genetic changes. Secondly, the demographics over the last 50 years have changed due to globalisation and significant migration to developed countries[7]. Disease presentation following migration offers a unique opportunity to further examine how environmental factors might influence disease expression in migrants.

Before undertaking further studies on migrant populations, we sought to summarise the current literature on IBD manifestation after migration to developed countries. Well-recognised large migrant groups have moved from Mexico to the United States and from India to the United States, Europe and the Middle East[7]. This environmental change can increase the risk of certain diseases. For example, the Indian migrant group has been studied extensively for cardiovascular disease, with associated significant increased risk[8,9]. Migrant communities are largely based on colonial and post-colonial history, cultural and economic ties. When relating to diseases, the distinction between migrants, ethnic group and race is unclear and yet important[10].

The designation of ‘migrants’ refers to people who move to a new country as a first generation or second generation when born there. Sometimes migrants converge and live within a social community based on historical and cultural ties (e.g., from India or Pakistan to the United Kingdom). The word ‘ethnicity’ derives from the Greek word ethnos, meaning a nation, people or tribe. It represents a multifaceted concept, with emphasis on shared origins or social background, shared cultural traditions and common language. Not all ethnic groups are migrants, instead the term reflects a social categorisation rather than a biological one[10]. In contrast the term ‘race’, first described by Hippocrates over 2000 years ago, classifies man biologically, according to physical characteristics such as face shape and colour. As there may be an overlap between race, ethnicity and migration, we aimed to study the epidemiology of IBD in ethnic migrant and racial groups compared with the indigenous population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This review was registered on the PROSPERO database, with registration number CRD42014013975. A structured search of English language articles in the Medline Ovid database from 1946 to October 4th, 2016 was conducted. The Cochrane database was reviewed. The search strategy used the following MeSH headings and key words alone or in combination: inflammatory bowel diseases, Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis, epidemiology, incidence, prevalence, diagnosis, migration, race, ethnicity statistics and numerical data (Appendix 1). The reference list of identified studies and reviews were hand-searched and relevant articles included. The search strategy and data extraction was performed by two authors (Misra R and Arebi N). Only published full-text articles were included.

Study inclusion

(1) Hospital- and population-based studies comparing incidence and prevalence of UC and/or CD between migrant and indigenous populations; and (2) Studies comparing disease phenotype and disease behaviour by recognised classification between migrant and indigenous populations.

Data extraction

For each study, data was collected on study design and location; sampling frame; sample size and ethnic group by two authors (Misra R and Arebi N) (Appendices 2 and 3) For incidence studies, the incidence was measured as cases/100000 years. Prevalence was captured as cases per 100000. Phenotype was described using Montreal classification, with E1 to E3 for UC and by age (A1, A2), location (L1, L2, L3, L4) and behaviour (B1, B2, B3, -p) for CD. The proportion of patients with each disease phenotype was expressed as percentage for each group.

Terminology

The main groups in the studies were described as South Asian (SA), Asian, Hispanic, African-American and Caucasian. SA was defined by persons with a background from the Indian subcontinent: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Asians were defined by the continent of Asia, encompassing South East Asia and China as well as SA. The term ‘migrant’ in this review encompassed recently migrated communities, ethnic groups or race. ‘Ethnic groups’ refers to migrants living as communities (e.g., SA in the United Kingdom, as statistic registration is recorded as an ethnic group). ‘Race’ refers to migrants settled as mass communities, where over generations they have assimilated with the background communities (Hispanics, African-Americans).

Statistical analysis

The analysis was restricted to studies comparing the incidence between migrants and Caucasian groups. The incidence of CD and UC were described as rates, and pooled as a rate ratio to compare the incidence between two groups.

The χ2 test for heterogeneity was used to determine whether results from different studies varied significantly. Heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic, to express the percentage of the variability in effect estimates attributed to heterogeneity. The P-value from the test of heterogeneity is given, with the I2 value.

As there was significant heterogeneity between the studies, and the I2 statistic was high for both CD and UC, random effects models were used to assess the size of the difference between population groups.

Quality assessment

The quality of the incidence and prevalence studies were assessed by whether the diagnostic criteria were clearly defined or recognised criteria were used (Lennard-Jones and Copenhagen criteria). The method of migrant reporting and sample frame was also examined.

RESULTS

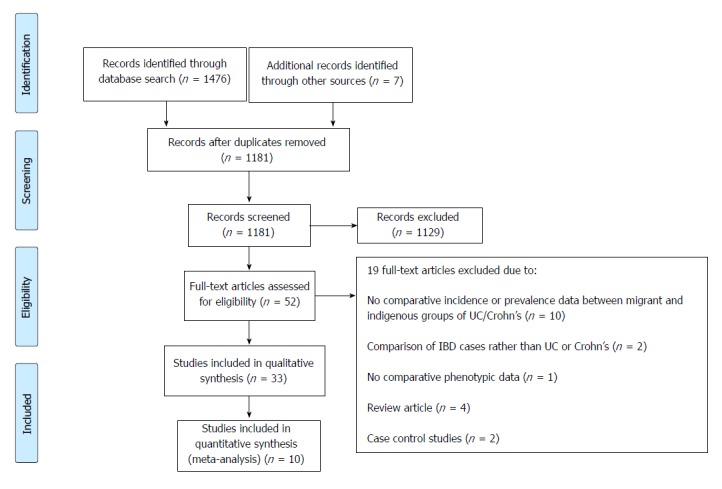

The PRISMA flow chart is shown in Figure 1. A total of 1181 abstracts were screened. Fifty-two full-text articles were retrieved, and 32 met the inclusion criteria in comparing incidence and prevalence of IBD and disease phenotype and behaviour between migrant and indigenous populations. Only 10 studies were suitable for the meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart. IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; UC: Ulcerative colitis.

Description of incidence and prevalence studies

There were 13 studies identified: 9 measured incidence[5,6,11-17] and 4 reported on prevalence[18-21] (Tables 1 and 2). Four studies examined both UC and CD[12,13,18,20] Eleven of twelve studies were retrospective, and only one was prospective[15]. Ten were conducted in single centres, with only two multicentre studies. Seven studies were carried out in the United Kingdom[5,6,11,14,15,17,18], four in North America[12,13,19,20] and the others in Fiji and Singapore[16,21]. The prevalence of IBD in the United Kingdom was only reported in one study[18].

Table 1.

Incidence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

| Study characteristics and demographics | Study quality characteristics | |||||||

| Study | Country (region) | Study period | Number of cases | Incidence rate/100000 | Diagnosis based on recognised criteria | Ethnicity reporting method | Sample frame | |

| SA | Caucasian | |||||||

| Crohn's disease | ||||||||

| Fellows (1985)[11] | United Kingdom (Derby) | 1966-1985 | 221 | 4.4 | 7.5 | No | Self-reported | Hospital |

| Probert (1992)[6] | United Kingdom (East London) | 1970-79 | 45 | 1.2 | 3.8 | Yes | Medical records | Hospital |

| 1980-89 | 54 | 2.3 | 3.8 | |||||

| Jayanthi (1992)[17] | United Kingdom (Leicester) | 1972-1980 | 80 | 1.2 | 3.5 | Yes | Surname | Population |

| 1981-1989 | 104 | 3.1 | 5.3 | |||||

| Pinsk (2007)[12] | Canada (Vancouver) | 1985-2005 | 397 (Paed) | 6.7 | 1.0 | Yes | Medical records | Hospital |

| Benchimol1 (2015)[13] | Canada (Ontario) | 1994-2010 | 12113 | 5.0 | 11.3 | No | Medical records | Population |

| Ulcerative colitis | ||||||||

| Probert (1992)[5] | United Kingdom (Leicester) | 1972-1989 | 1003 | 10.8 | 5.3 | No | Surname | Population |

| Jayanthi (1992)[14] | United Kingdom (East London) | 1972-1989 | 112 | 1.8 | 6.2 | No | Medical records | Hospital |

| Carr (1999)[15] | United Kingdom (Leicester) | 1991-1994 | 74 | 17.2 | 9.1 | Yes | Self-reported | Population |

| Pinsk (2007)[12] | Canada (Vancouver) | 1985-2005 | 120 (Paed) | 6.4 | 3.7 | No | Medical records | Hospital |

| Probert (1985)[16] | Fiji | 1985-1986 | 15 | 1.5 | 0.2 | No | Medical records | Hospital |

| Benchimol1(2015)[13] | Canada (Ontario) | 1994-2010 | 12713 | 2.0 | 11.4 | No | Medical records | Population |

SA compared to non-immigrant. Characteristics of studies comparing South Asian (SA) migrants and Caucasians.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Crohn’s disease: Study characteristics and comparison between Caucasian and other migrant groups

| Study characteristics | Study quality characteristics | ||||||||||

| Study | Country (region) | Study period | Number of cases | Prevalence rate, cases/100000 | Diagnosis based on recognised criteria | Ethnicity reporting method | Sample frame | ||||

| SA | Asian | Caucasian | Black | Hispanic | |||||||

| Probert (1993)[18] | United Kingdom (Leicester) | 1989 | 676 | 33.2 | - | 75.8 | - | - | Yes | Self-reported | Population |

| Kurata (1992)[19] | United States (California) | 1982-1988 | 169 | - | 5.6 | 43.6 | 29.8 | 4.1 | No | Medical records | Hospital |

| Wang (2013)[20] | United States (National Database) | 1996-2007 | 204 | - | 45.0 | 154.0 | 68.0 | 15.0 | No | Self-reported | Population |

SA: South Asian.

Study quality characteristics

Quality characteristics of the studies are shown in Tables 1-3. One study looked at CD and UC incidence, and two studies looked at CD and UC prevalence. Six of thirteen studies used recognised diagnostic criteria[5,6,12,15,17,21]. Migrant status was self-reported in five studies[11,15,18,20,21] and taken from medical records in six studies[6,12-14,16,19]. Two studies relied on patient surname to identify migrant origin[5,17]. The sample frame was population-based in six[5,13,15,17,18,20] and hospital-based in seven studies[6,11,12,14,16,19,21].

Table 3.

Prevalence of ulcerative colitis: Study characteristics and comparison between population groups

| Study characteristics | Study quality characteristics | ||||||||||

| Study | Country (region) | Study period | Number of cases | Prevalence rate, cases/100000 | Diagnosis based on recognised criteria | Ethnicity reporting method | Sample frame | ||||

| SA | Asian | Caucasian | Black | Hispanic | |||||||

| Probert (1993)[18] | United Kingdom (Leicester) | 1989 | 888 | 136.0 | - | 90.8 | - | - | Yes | Self-reported | Population |

| Wang (2013)[20] | United States (National database) | 1996-2007 | 108 | - | 40.0 | 89.0 | 25 | 35 | No | Self-reported | Population |

| SA | Malay | Chinese | Black | Hispanic | |||||||

| Lee (2000)[21] | Singapore (Singapore) | 1985-1996 | 58 | 16.2 | 7.0 | 6.0 | - | - | Yes | Self-reported | Hospital |

SA: South Asian.

Incidence of CD

Most studies reporting the incidence of CD (3/5) were from the United Kingdom (Table 1), with a predominant SA migrant group[6,11,17]. The remaining two studies from Canada described the SA paediatric population[12], and one study compared non-immigrants to SA[13]. The incidence of CD in SAs was consistently lower than Caucasian, except for one Canadian paediatric study[12]. The Benchimol study showed a lower incidence in SA compared to other groups within the same environment[13]. The two United Kingdom studies where the incidence was examined over two time periods showed an increase in the incidence of CD in the SA population, from 1.2 to 2.3/100000 in East London and 1.2 to 3.1/100000 in Leicester[6,17]. The last migrant United Kingdom incidence studies were published in 1989.

Incidence of UC

There were six studies reporting the incidence of UC (Table 1). The incidence was higher for SAs when compared with Caucasians (three studies) and Melanesians in one study from Fiji[5,12,15,16]. In the only prospective study, the incidence was significantly higher and although this was a small study (74 cases) it was also the most recent[15]. This may indicate a rising incidence. Two studies showed a lower UC incidence, one in the Bangladeshi population in East London[14] and the other in Ontario, Canada[13].

Meta-analysis of CD incidence studies

We performed a meta-analysis on studies comparing SA migrant and Caucasian groups, which consisted of four studies. Two studies looked at incidence over 2 separate decades. Each decade was counted as a separate study and the analysis was undertaken as six studies[5,6]. The Benchimol study[13] was excluded as the comparator group and was classified as non-immigrant rather than a specifically named ethnic/migrant group.

The overall rate ratio for CD (0.78, 95%CI: 0.22-2.78) showed a trend towards a lower incidence in the adult SA group in comparison to the Caucasian group (Table 4). The individual studies all showed lower incidence rates, except for one study in a paediatric population which showed a higher incidence in the SA population[12].

Table 4.

Meta-analysis of incidence studies showing rate ratio of South Asians relative to Caucasians

| Disease | Number of studies |

Heterogeneity |

Effect size |

||

| I2 | P value | RR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Crohn’s disease | 6 | 95% | < 0.001 | 0.78 (0.22, 2.78) | 0.7 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 4 | 83% | 0.001 | 1.39 (0.84, 2.32) | 0.2 |

Meta-analysis of UC incidence studies

Analysis of the four studies for UC showed an overall rate ratio of 1.39 (95%CI: 0.84-2.32), indicating a trend towards a higher rate of UC in the SA population (Table 4). All but one study reported a higher incidence for UC in SA. In the outlier study[9], the population was exclusively a Bangladeshi subgroup of the SA population, unlike the other studies where the population was predominantly North Indian.

Prevalence of CD

Three studies reported on CD prevalence. Two were from the United States, where the prevalence rate for Asian, Black or Hispanic populations was lower than for Caucasians[19,20] (Table 2). The remaining study from the United Kingdom showed a lower prevalence in Caucasians than SA compared to Caucasians[18]. This is consistent with the reportedly lower SA CD incidence from the same population in Leicester at approximately the same time period[17] (Table 1).

Prevalence of UC

There were four studies reporting on UC prevalence, with diverging results (Table 4). The only United Kingdom study showed a higher prevalence for UC in SAs compared with the local population[18]. A separate study from Singapore reported a higher prevalence in SAs than Chinese and Malay groups[21]. In contrast in the United States, the UC prevalence was lower for Asians, Hispanics and Blacks compared with the Caucasian group[20].

Description of disease phenotype studies

There were 20 studies examining disease phenotype in relation to migrants or race (Tables 5 6 7 8 and 9). Fourteen studies were conducted in the United States[22-34] and four in the United Kingdom[15,35-37], with the remaining two from Canada and Malaysia[38,39]. Sixteen studies were single centre, three multicentre[24,31,35] and only one was prospective[15]. Majority of the studies reported on both UC and CD, with 15 reporting on UC and 16 on CD.

Table 5.

Crohn’s disease location and behaviour

| Study | Country (Region) | Time period | Number of cases | Montreal classification |

Population groups, % |

|

| SA | Caucasian | |||||

| Location | ||||||

| Walker (2011)[35] | United Kingdom (NW London) | 2008-2010 | 309 | L1 | 16.0 | 24.7 |

| L2 | 46.8 | 34.8 | ||||

| L3 | 37.2 | 40.5 | ||||

| L4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Goodhand (2012)[36] | United Kingdom (East London) | 2010 | 141 | L1 | 33.0 | 32.0 |

| L2 | 24.0 | 43.0 | ||||

| L3 | 38.0 | 22.0 | ||||

| L4 | 18.0 | 13.0 | ||||

| Li (2013)[22] | United States (San Francisco) | 1994-2009 | 57 (Paed) | L1 | 7.7 | 14.9 |

| L2 | 38.5 | 23.4 | ||||

| L3 | 53.9 | 61.7 | ||||

| L4 | 15.4 | 5.3 | ||||

| Carroll (2016)[38] | Canada (British Columbia) | 1997-2012 | 638 (Paed) | L1 | 6.0 | 9.0 |

| L2 | 55.0 | 35.0 | ||||

| L3 | 39.0 | 55.0 | ||||

| L4a | 55.0 | 43.0 | ||||

| L4b | 1.0 | 9.0 | ||||

| L4ab | 0.0 | 8.0 | ||||

| Behaviour | ||||||

| Walker (2011)[35] | United Kingdom (NW London) | 2008-2010 | 309 | B1 | 72.3 | 58.1 |

| B2 | 22.0 | 60.0 | ||||

| B3 | 4.3 | 14.0 | ||||

| Perianal | 20.2 | 21.4 | ||||

| Goodhand (2012)[36] | United Kingdom (East London) | 2010 | 141 | B1 | 63.0 | 55.0 |

| B2 | 15.0 | 11.0 | ||||

| B3 | 20.0 | 15.0 | ||||

| Perianal | 16.0 | 3.0 | ||||

| Li (2013)[22] | United States (San Francisco) | 1994-2009 | 57 (Paed) | Perianal | 46.2 | 12.8 |

| Carroll (2016)[38] | Canada (British Columbia) | 1997-2012 | 638 (Paed) | B1 | 61.0 | 73.0 |

| B2 | 13.0 | 16.0 | ||||

| B3 | 6.0 | 3.0 | ||||

| B2B3 | 21.0 | 9.0 | ||||

South Asians compared with Caucasians. Total No. of cases reported was 1145. Significant difference in disease behaviour illustrated in bold.

Table 6.

Crohn’s disease location

| Study | Country (Region) | Time period | Number of cases | Disease location/ Behaviour, Montreal |

Population groups, % |

||

| AA | Caucasian (or other control) | Hispanic | |||||

| Cross (2006)[23] | United States (Baltimore) | 1997-2005 | 210 | L1 | 13.0 | 38.0 | - |

| L2 | 29.0 | 23.0 | - | ||||

| L3 | 56.0 | 36.0 | - | ||||

| Sofia (2014)[40] | United States (Chicago) | 2008-2013 | 1334 | L1 | 57.8 | 71.0 | - |

| L2 | 60.6 | 66.0 | - | ||||

| Nguyen (2006)[24] | United States (National) | 2003-2005 | 697 | L1 | 16.1 | 29.2 | 23.3 |

| L2 | 33.9 | 17.4 | 16.3 | ||||

| L3 | 22.6 | 36.7 | 52.3 | ||||

| L4 | 27.4 | 16.7 | 8.1 | ||||

| Eidelwein (2007)[25] | United States (Baltimore) | 1991-2000 | 137 (Paed) | L1 | 3.0 | 2.9 | - |

| L2 | 73.5 | 71.8 | - | ||||

| L3 | 23.5 | 25.2 | - | ||||

| Hatter (2012)[26] | United States (Texas) | 2004-2009 | 246 (Paed) | L1 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 4.8 |

| L2 | 7.1 | 4.8 | 10.5 | ||||

| L3 | 87.8 | 88.9 | 84.2 | ||||

| Ghazi (2013)[27] | United States (Baltimore) | 2004-2009 | 296 | L1 | 31.0 | 38.0 | - |

| L2 | 12.0 | 20.0 | - | ||||

| L3 | 55.0 | 42.0 | - | ||||

| Damas (2013)[28] | United States (Florida) | 1998- 2009 | 325 | L1 | - | 16 (NHW) | 24.4 |

| L2 | - | 24.0 | 25.6 | ||||

| L3 | - | 60.0 | 50.0 | ||||

| L4 | - | 12.5 | 3.9 | ||||

| Kugathasan (2003)[29] | United States (National) | 2000-2001 | 222 (Paed) | L1 | 10.0 | 19.0 | - |

| L2 | 34.0 | 28.0 | - | ||||

| L3 | 46.0 | 51.0 | - | ||||

| L4 | 32.0 | 42.0 | - | ||||

AA or Hispanics compared with Caucasians (3467 total cases). Bold font shows significant differences between AA and population group. Italic font illustrates significant difference between Hispanic and Caucasian groups. AA: African-Americans; NHW: Non-Hispanic white.

Table 7.

Crohn’s disease behaviour

| Study | Country (Region) | Time period | Number of cases | Disease location/ Behaviour, Montreal |

Population groups, % |

||

| AA | Caucasian | Hispanic | |||||

| Nguyen (2006)[24] | United States (National) | 2003-2005 | 697 | B1 | 53.2 | 48.0 | 45.3 |

| B2 | 27.9 | 21.4 | 23.6 | ||||

| B3 | 19.0 | 30.6 | 31.1 | ||||

| Perianal | 40.0 | 28.7 | 52.5 | ||||

| Eidelwein (2007)[25] | United States (Baltimore) | 1991-2000 | 137 (Paed) | B2 + B3 | 29.1 | 11.11 | - |

| Ghazi (2013)[27] | United States (Baltimore) | 2004-2009 | 296 | B1 | 18.0 | 33.0 | - |

| B2 | 42.0 | 36.0 | - | ||||

| B3 | 40.0 | 31.0 | - | ||||

| Perianal | 36.0 | 25.0 | - | ||||

| Sofia (2014)[40] | United States (Chicago) | 2008-2013 | 1334 | Perianal | 25.7 | 24.7 | - |

| Damas (2013)[28] | United States (Florida) | 1998- 2009 | 325 | B1 | - | 81.5 (NHW) | 78.9 |

| B2 | - | 0.0 | 1.1 | ||||

| B3 | - | 18.5 | 20.0 | ||||

| Perianal | - | 27.0 | 23.0 | ||||

| Kugathasan (2005)[29] | United States (National) | - | 222 (Paed) | Inflammatory | 58.0 | 64.0 | - |

| Stricturing | 20.0 | 18.0 | - | ||||

| Fistulising | 22.0 | 18.0 | - | ||||

| Perianal | 23.0 | 36.0 | - | ||||

| Malaty (2010)[30] | Houston (Texas) | 2000-2006 | 273 | Inflammatory | 64.0 | 63.0 | 58.0 |

| Stricturing | 16.0 | 17.0 | 13.0 | ||||

| Fistulising | 17.0 | 16.0 | 32.0 | ||||

| Adler (2016)[31] | Multicentre (United States and United Kingdom) | 2006-2014 | 2034 (Paed) | Perianal | 26.0 | 20.0 | 24.0 |

AA or Hispanics compared with Caucasians (5318 cases). Italic font illustrates significant differences between hispanic and population group. Bold font shows significant differences between AA and other population group. AA: African-Americans.

Table 8.

Ulcerative colitis in Caucasian and South Asian migrant groups (1054 cases)

| Study | Country (Region) | Study period | Number of cases | Disease extent, Montreal |

Ethnic groups, % |

|

| SA | Caucasian (or other control) | |||||

| Adult | ||||||

| Carr (1999)[15] | United Kingdom (Leicester) | 1991-1994 | 74 | E1 + E2 | 63.7 | 68.3 |

| E3 | 36.3 | 31.7 | ||||

| Rashid (2008)[37] | United Kingdom (Manchester) | 2008 | 82 | E3 | 41.0 | 26.0 |

| Walker (2011)[35] | United Kingdom (NW London) | 2008-2010 | 461 | E1 | 9.9 | 26.1 |

| E2 | 27.1 | 31.4 | ||||

| E3 | 63.0 | 42.0 | ||||

| Goodhand (2012)[36] | United Kingdom (East London) | 2010 | 89 | E1 | 2.0 | 31.0 |

| E3 | 60.0 | 33.0 | ||||

| Hilmi (2009)[39] | Malaysia (Malaysia) | 2004-2005 | 118 | E1 + 2 | 39.6 | 56.7 (Malay) |

| E3 | 60.4 | 43.4 (Malay) | ||||

| Paediatric | ||||||

| Carroll (2016)[38] | Canada (British Columbia) | 1997-2012 | 230 | E1 | 3.0 | 5.0 |

| E2 | 9.0 | 19.0 | ||||

| E3 | 12.0 | 18.0 | ||||

| E4 | 77.0 | 58 (Non-South Asian) | ||||

Adult and paediatric studies on disease extent. Bold font shows significant differences between AA and population group (809/1054 cases). AA: African-American; SA: South Asian.

Table 9.

Ulcerative colitis in AA and Hispanic groups (1787 cases)

| Study | Country (Region) | Time period | Number of cases | Disease extent |

Ethnic groups, % |

||

| AA | Caucasian | Hispanic | |||||

| Adult studies | |||||||

| Basu (2005)[32] | United States (Texas) | 1999-2003 | 61 | E1 | - | 32.0 | 8.0 |

| E2 + 3 | - | 68.0 | 86.0 | ||||

| Nguyen (2006)[24] | United States (National database) | 2003-2005 | 396 | E1 | 13.8 | 5.9 | 3.6 |

| E2 | 16.4 | 31.4 | 34.5 | ||||

| E3 | 51.7 | 62.7 | 80.0 | ||||

| Eidelwein (2007)[25] | United States (Baltimore) | 1991-2000 | 40 | E1 + 2 | 0.0 | 10.0 | - |

| E3 | 100.0 | 23.0 | - | ||||

| Moore (2012)[33] | United States (Ohio) | 2000-2010 | 311 | E1 | 14.5 | 6.5 | - |

| E2 | 44.7 | 30.7 | - | ||||

| E3 | 40.8 | 62.9 | - | ||||

| Sofia (2014)[40] | United States (Chicago) | 2008-2013 | 541 | E1 | 17.9 | 11.1 | - |

| E2 | 28.6 | 32.0 | - | ||||

| E3 | 50.0 | 51.5 | - | ||||

| Damas (2013)[28] | United States (Florida) | 1999-2009 | 138 | E1 | - | 11.8 | 12.5 |

| E2 | - | 29.4 | 46.2 | ||||

| E3 | - | 58.8 | 41.3 | ||||

| Paediatric | |||||||

| Flasar (2008)[34] | United States (Baltimore) | 1997-2005 | 197 | E1 | 23.0 | 10.0 | - |

| E2 | 23.0 | 31.0 | - | ||||

| E3 | 53.0 | 59.0 | - | ||||

| Hatter (2012)[26] | United States (Texas) | 2004-2009 | 103 | E1 + 2 | 7.1 | 15.4 | 18.8 |

| E3 | 81.3 | 84.6 | 81.3 | ||||

Adult and paediatric studies on disease extent. Italic font illustrates significant difference between Hispanic and Population group. Bold font shows significant differences between AA and population group. AA: African-American.

CD

The phenotype was studied for location and behaviour. Comparisons are presented for SA, African-Americans or Hispanics and Caucasians depending on the country where the studies were conducted.

SA group was compared with Caucasians in four studies and all reported on both location and disease behaviour (Table 5). Two were from the United Kingdom[35,36], one from the United States[22], and one from Canada[38]. Two studies (United Kingdom and Canada) showed SA significantly more likely to have colonic disease[35,38]. These two studies contained 947 cases of the 1147 pooled population. The Canadian study also showed that SA had less ileal involvement[38]. There was no other significant difference in disease location. For behaviour, one United Kingdom study showed SA had less stricturing (B2) and less non-penetrating disease (B3), but this was not significant[35]. In contrast, perianal disease was significantly more common in SA compared with Caucasians in two studies[22,36]. The Canadian paediatric study, which included 638 cases, indicated a more complicated disease behaviour for SA, where B2 and B3 disease was noted in 21% of SA compared with 9% of Caucasians[38].

African-American and Caucasian groups were compared for disease location in eight studies (Table 6), all from the United States, three of which were in paediatric populations[25,26,29]. Disease behaviour in eight studies is shown in Table 7. African-Americans showed significantly less ileal disease (L1) in three studies[23,24,40] from a population of 2241 cases (65%) out of the total cohort of 3467 cases studied. African-Americans showed more significantly more stricturing (B2) and penetrating disease (B3) in one study[25] and perianal disease in two studies[24,31] (Table 7).

Hispanic and Caucasians were compared for disease location in only three studies (Table 6) and behaviour in four studies (Table 7). Hispanics showed significantly lower rates for ileal disease and higher rate of colonic disease compared with Caucasians in one study population of 697 cases[24]. Perianal presentation was significantly more frequent in Hispanics in only 2/4 studies but these studies represented 92% of the studied cohorts (7376/7974)[24,31]. In another study of 325 cases, they were significantly less likely to have upper gastrointestinal disease[28].

UC

The UC studies described disease extent. Results were presented for SA, African-Americans or Hispanics compared with Caucasian or indigenous adult and paediatric populations (Tables 8 and 9). SA and Caucasian (or Malay in one study) groups were compared in six studies, including four in the United Kingdom[15,35-37] and one in Malaysia[39] and a further study in Canada which was limited to a paediatric population[38] (Table 8). In all six studies there were more SA with pan-colonic disease than Caucasians; this was a significant finding in four studies[35,36,38,39], which represented 898/1054 cases (85%) of the pooled population.

African-Americans were compared to Caucasians in six studies, of which two were paediatric (Table 9). Four studies described a higher proportion of African-Americans having disease limited to the rectum[25,26,32,33], which was a significant finding in one study[33].

Hispanics were compared with Caucasians in four studies. In the Hispanic group, two studies showed no difference in disease location for UC[26,28], another significantly less proctitis[32], with a fourth study demonstrating a significantly increased risk of pan-colitis and higher colectomy rate (32.3% vs 15.8%, P < 0.01)[24].

DISCUSSION

This review indicates a difference in disease incidence, prevalence and phenotypes between migrants and non-migrants in individual studies. This has two important implications. Firstly, increased migration may alter disease burden within a population and impact health policy decisions. Secondly, deeper investigation of migrant populations may provide insight into the role of environmental change and diet in the aetiology of IBD.

We identified the main migrant populations with IBD reported in the literatures as SA, African-Americans and Hispanics. The SA population has a wide diaspora and countries such as United Kingdom, Canada, Singapore, Malaysia and Fiji report the presentation of IBD.

The SA group seems to be particularly susceptible to developing UC, with a higher incidence than the local population in the United Kingdom and Canada. The incidence was only lower in two populations. The first was in east London, which was restricted to the Bangladeshi group and therefore may be a reflection of a distinct ethnic group. The second was in Ontario, Canada, which compared SA to the non-immigrant population[13]. The non-immigrant population had a higher UC incidence rate (11.4/100000) than the Caucasian group in the other Canadian study (3.7/100000). A possible explanation is that immigration data was only available from 1985 onwards. Immigrants who arrived to Canada before 1985 were considered as non-immigrants. It is noteworthy that the likelihood of UC increased the younger age of arrival of the immigrant.

Whilst there were fewer studies on prevalence, both reported higher prevalence for SA as would be expected for the higher incidence rate[18,21]. When the data was pooled, the summary measures also illustrated a trend towards a higher rate of UC in the SA population compared to Caucasians (Table 4). The outlier study consisted of a Bangladeshi ethnic group, and excluding this study showed a consistently higher incidence of UC in SA; but, we did not repeat the meta-analysis on the three remaining studies as the result would be questionable, due to bias and error.

Data on African-Americans and Hispanics was limited for disease incidence and prevalence, and no conclusions could be drawn. Only one study from the United States described UC prevalence in African-Americans and Hispanics, which was lower for each group than the Caucasian population[20]. Two separate disease phenotype studies in Hispanics reported less proctitis in one and more colonic disease in the other. The parallel results would suggest that the Hispanic race exhibits more extensive disease. Disease extent was different for African-Americans, as the only study reporting on it showed that most African-Americans had rectal disease. Similar to the Hispanic group, the large SA population showed significantly more pan-colonic disease. Overall, these findings imply a higher rate of colonic disease in Hispanics and SA migrants.

An interesting observation borne out by studies in Leicester, North West London and British Columbia[18,35,38] is that the well documented increase in pan-colonic disease did not translate into higher colectomy rate, as would be expected. However, the two Hispanic studies in this review showed more colonic disease, and the one that studied colectomy rate reported a higher colectomy rate for UC as would be expected with a higher prevalence of pan-colonic disease[24].

In addition, we recently published data generated from a national database showing a higher rate of colectomy in a SA cohort in the United Kingdom[41].

In contrast to the UC incidence rate, the incidence of CD seems to be consistently lower in SA than Caucasians. Only one study showed a higher incidence rate[12]. This was a paediatric population, where the incidence of CD in the background population was much lower (1.0/10000) than in a parallel Canadian study (11.3/100000). It is plausible to speculate that it may reflect earlier disease onset for second generation migrants. The meta-analyses suggested no strong evidence of a difference in the incidence of the pooled CD data. Were the outlier study by Pinsk et al[12] to be excluded, there would be a consistently lower incidence of CD in SAs. The lower prevalence in the United Kingdom is consistent with the lower CD incidence for SA. In the United States, prevalence for Asians was lower but this group is broader and includes South East Asians and Pacific Asians.

The phenotypic pattern shows more colonic, less ileal disease, more perianal and more penetrating and stricturing disease in SA, with evidence collated from different studies. The two independent observations of more colonic disease and perianal disease in SA are supportive of more aggressive disease in this group. Similarly, the African-Americans had significantly less TI disease, inferring more colonic disease. There was more perianal disease, and even though this stems from only two studies, they represent 65% of the studied cases. The Hispanics also show more colonic and perianal disease. Overall, migrants seem to be less likely to have CD, but when it presents it tends to be more aggressive with colonic and perianal location and complex behaviour.

The prevalence studies show UC and CD to be more prevalent in Caucasians compared to Black and Hispanic groups and UC is more common in SA groups. Comparing the two CD United States studies[19,20], a significant increase in prevalence was shown over time in all groups. There has only been one United Kingdom prevalence study, which was performed in 1989, and the last United States study was over 10 years ago. Newer studies are needed to update the emergence of disease.

Differences in phenotype were noted between first and second generation SA migrants. In second generation migrants in Leicester, extensive colitis was more common than in the first generation, which was similar to that seen in Caucasians[15]. The disease pattern followed that of the indigenous population after only one generation and conveys the influence of environmental factors on disease expression. However, these findings were not replicated in Northwest London less than a decade later. UC disease phenotype in first generation SA diagnosed within 10 years of migration was similar to second generation SA, even though the dominant phenotype was extensive colitis in both generations[35]. When the authors performed a subgroup analysis on first generation patients, the rates of diagnosis in the first, second and third decades after migration were comparable and, somewhat unexpectedly, there was no significant increase in disease diagnosis with time spent in the United Kingdom. This result, in conjunction with similar disease phenotype, led the authors to speculate that perhaps genetic susceptibility had a more important role to play. Indeed, novel UC risk alleles have been identified specifically in the North Indian population[42]. A recent genome-wide specific study has shown African-specific loci for UC[43], demonstrating the importance of studying non-European populations to better understand the disease.

Limitations of the study

The quality assessment of the incidence and prevalence studies revealed significant weaknesses in the body of evidence. Almost all the studies are retrospective and, therefore, subject to case ascertainment bias. Only six of thirteen studies used recognised diagnostic criteria, and the majority of the studies were hospital- rather than population-based and relied on ethnicity reporting through medical records or surname recognition. There is a risk of information bias as data may have been collected by different people, especially in the studies spanning a longer time period. Differential loss of follow up is also another source of bias.

Standard disease classification systems, such as Montreal classification, were not used in all studies. Moreover, the prevailing studies have failed to address several confounding variables-medication, smoking, diet, patient choice and clinical decision-making, all of which could affect disease phenotype-and other markers of severe disease, such as requirement for surgery. Moshkovska et al[44] demonstrated that SA patients had significantly higher concerns with 5-ASA treatments than non-Asian patients, and SA ethnicity was independently associated with non-adherence, which is relevant as differential exposure to 5-ASA may contribute to more extensive disease. Diagnostic delay increases the risk of Crohn’s-related surgery[27], and if access to medical care is limited for certain ethnic groups, it may explain a more aggressive phenotype. Smoking habits differ between ethnic groups. For instance, in the United Kingdom, an estimated 40% of Bangladeshi men regularly smoke compared to the national average of 24%[45]. This would be expected to increase susceptibility to Crohn’s rather than UC in this group and would may explain the predominant perianal phenotype observed in Bangladeshis in East London[36].

The other limitation rests with terminology and terms used within each study, depending on the population studied. ‘Hispanic’ is a broad term that can include people from Mexico, Puerto Rico or Cuba. This is an example of a social construct of Hispanic ethnicity, which may not reflect the genetic background of the population. Better categorisation of these groups, according to country of origin, is required to determine whether there are differences. In the African-Americans, the distinction between whether the patients were migrants or second generation was not clear and as we have seen in the SA group, this can impact on disease phenotype. Apart from the SA group, the phenotypic studies do not show clear differences in comparison to Caucasians. Within the Hispanic and African-American groups, the phenotypic results are discordant, which may reflect the heterogeneity of the population.

This review, with its attendant limitations, demonstrated the absence of high-quality, prospective, population-based epidemiological studies on this topic. The ACCESS[4] and Epicom[46] studies are exemplary recent prospective multicentre cohorts studies that generated new insights into the incidence of IBD in Asia-Pacific and Europe; however, they did not report on migrants. We, subsequently, conducted a retrospective review of the Epicom study population, whereby migrant status was re-examined. We noted a higher than expected incidence of IBD in the migrant population, even though the number of migrants in the majority of countries was still low[47]. Conversely, a recent paper describing the study of movement of migrants from high to low incidence areas (Faroe Islands to Denmark) has shown a significant impact on UC disease risk. Excess risk of UC was nearly doubled during the immigrants’ first 10 years, but after 10 years the immigrants’ UC risk was similar to that of Danes. In this study, the removal of an unknown exposure has caused a dramatic shift in the incidence, emphasising the importance of environmental factors[48].

The key change with migration is exposure to a different environment. This may be driven by factors that change with urbanisation, namely diet, lifestyle (smoking, alcohol) and hygiene, among others. The diet and its change with migration deserves further examination. Where migrants form an ethnic enclave, it may remain unaltered. When they integrate with the local population, they may adopt the prevailing western diet. Exposure to western diet can be studied by its migration to the east. This tends to be associated with rapid urbanisation, as seen in areas such as Guangzhou, China, where the incidence of IBD has recently risen[4].

Mounting evidence from animal models and human studies indicates an overarching effect of diet on the gut microbiota. Agus et al[49] showed how a western diet induces changes in gut microbiota composition, alters host homeostasis and promotes adherent invasive gut colonisation in genetically-susceptible mice. In healthy volunteers, 2 wk of either exclusive animal or plant product consumption altered the microbial community structure and overcame inter-individual differences in microbial gene expression[50]. In migrant populations, dietary change may exert a more profound aetio-pathogenic effect, which is largely unexplored in this population group in conjunction with a dearth of detailed dietary data on ethnic groups with IBD. Accurate dietary data is difficult to obtain without an interviewer-led, time-consuming questionnaire. Large scale epidemiological studies often neglect this area in favour of collecting other and easily accessible information.

Studying the diet in migrant populations may provide clues to modifiable risk factors in the development of IBD. Whilst this may appear to be straightforward, in reality it is challenging to explore because patients significantly change their diets at diagnosis, with consequential effects on microbial composition[51]. This confounder needs to be recognised and minimised when studying ethnicity and alterations in the microbiota by recording supervised dietary intake. Other environmental factors, such as urbanisation and hygiene, may also influence the microbiome but studying how they do so is more challenging. We suggest looking at the endpoint of genetic and environmental factors by examining the function of microbiota through metabolic profiles in migrant patients.

A link between distinct microbial patterns and migration may partly explain the differences in disease phenotype described in this review. Two studies reported different microbial profiles for ethnic groups[52,53]. A further study demonstrated that these compositional differences can drive metabolic and immune activities, which can be related to disease severity[54]. Confounders such as smoking, diet, medications, disease phenotype and severity that affect the microbiota were not analysed separately within these studies, due to the small numbers of patients.

The potential role of environmental factors on microbial colonisation is an area of increasing interest[55]. Studying these early life perturbations in a genetically predisposed population, such as second generation migrants, bought up in a ‘western’ environment, for example SA, may help to decipher the impact of genetic and environmental factors. A prospective inception cohort to describe real-time epidemiological features of IBD will address the limitations observed in this systematic review. Parallel in-depth analysis of microbial factors may show a specific microbial profile related to migration and explain the differing disease phenotype, whilst addressing the confounding factors.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Epidemiologic studies suggest an increasing incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in developed countries. Some studies have reported a change in migrants moving from developing low incidence countries to developed high incidence countries, whereby they exhibit the incidence of the adopted country. This implies there may be an environmental trigger for the disease, as the onset is too rapid to be accounted for by genetic changes.

Research motivation

Disease presentation following migration offers a unique opportunity to examine how environmental factors might influence disease expression in migrants. Describing epidemiological changes in migrant groups may identify susceptible ethnic groups and help target further studies.

Research objectives

The authors sought to summarise the current literature on IBD manifestation after migration to developed countries. As there may be an overlap between race, ethnicity and migration, we aimed to study epidemiology of IBD in ethnic migrant and racial groups compared with the indigenous population.

Research methods

A systematic review using PRISMA guidelines was undertaken. Studies on incidence, prevalence and disease phenotype of migrants and race compared with indigenous groups were eligible for inclusion. A statistical meta-analysis comparing the incidence between migrants and Caucasian groups was performed.

Research results

Thirty-three studies met the inclusion criteria. South Asians showed consistently higher incidence than indigenous groups for ulcerative colitis (UC). Pooled analysis could only be undertaken for incidence studies on South Asians compared to Caucasians. There was significant heterogeneity between the studies [95% for UC, 83% for Crohn’s disease (CD)]. The difference between incidence rates was not significant, with a rate ratio for South Asian:Caucasian of 0.78 (95%CI: 0.22-2.78) for CD and 1.39 (95%CI: 0.84-2.32) for UC. In six studies, there were more South Asians with pan-colonic disease than Caucasians, and this was a significant finding in four studies. A similar pattern was observed for Hispanics in the United States. Bangladeshis and African-Americans showed an increased risk of CD with perianal disease.

Research conclusions

This the first study to show consistent differences in disease incidence, prevalence and phenotypes between migrants and non-migrants. The South Asian migrant population are particularly susceptible to developing UC. This review has demonstrated the absence of high-quality, prospective, population-based epidemiological studies on this topic. Investigation of migrant populations may provide insight into the role of environmental change and diet in the aetiology of IBD.

Research perspectives

A prospective inception cohort to describe real-time epidemiological features of IBD will address the limitations observed in this systematic review. The potential role of environmental factors on microbial colonisation is an area of increasing interest. Studying second generation migrants bought up in a ‘western’ environment, for example South Asians, may help to decipher the impact of genetic and environmental factors. Parallel in-depth analysis of microbial factors may show a specific microbial profile related to migration and explain differing disease phenotype, whilst addressing confounding factors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Paul Bassett for providing statistical support.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest declared.

Peer-review started: August 28, 2017

First decision: October 10, 2017

Article in press: November 21, 2017

P- Reviewer: Krishnan T, Specchia ML S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Huang Y

Contributor Information

Ravi Misra, Department of Gastroenterology, St. Marks Academic Institute, London HA1 3UJ, United Kingdom.

Omar Faiz, Surgical Epidemiology, Trials and Outcome Centre, St. Marks Academic Institute, London HA1 3UJ, United Kingdom.

Pia Munkholm, Department of Gastroenterology, North Zealand University Hospital, Frederikssund Frederikssundsvej 30, Denmark.

Johan Burisch, Department of Gastroenterology, North Zealand University Hospital, Frederikssund Frederikssundsvej 30, Denmark.

Naila Arebi, Department of Gastroenterology, St. Marks Academic Institute, London HA1 3UJ, United Kingdom. naila.arebi@imperial.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:307–317. doi: 10.1038/nature10209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Wajda A. Epidemiology of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a central Canadian province: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:916–924. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54.e42; quiz e30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, Wong M, Chow CM, Hui AJ, Wong TC, Leung VK, Tsang SW, Yu HH, Li MF, Ng KK, Kamm MA, Studd C, Bell S, Leong R, de Silva HJ, Kasturiratne A, Mufeena MN, Ling KL, Ooi CJ, Tan PS, Ong D, Goh KL, Hilmi I, Pisespongsa P, Manatsathit S, Rerknimitr R, Aniwan S, Wang YF, Ouyang Q, Zeng Z, Zhu Z, Chen MH, Hu PJ, Wu K, Wang X, Simadibrata M, Abdullah M, Wu JC, Sung JJ, Chan FK; Asia-Pacific Crohn’s and Colitis Epidemiologic Study (ACCESS) Study Group. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn’s and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:158–165.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Probert CS, Jayanthi V, Pinder D, Wicks AC, Mayberry JF. Epidemiological study of ulcerative proctocolitis in Indian migrants and the indigenous population of Leicestershire. Gut. 1992;33:687–693. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.5.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Probert CS, Jayanthi V, Pollock DJ, Baithun SI, Mayberry JF, Rampton DS. Crohn’s disease in Bangladeshis and Europeans in Britain: an epidemiological comparison in Tower Hamlets. Postgrad Med J. 1992;68:914–920. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.68.805.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis KF, D’Odorico P, Laio F, Ridolfi L. Global spatio-temporal patterns in human migration: a complex network perspective. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pais P, Pogue J, Gerstein H, Zachariah E, Savitha D, Jayprakash S, Nayak PR, Yusuf S. Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in Indians: a case-control study. Lancet. 1996;348:358–363. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)02507-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernando E, Razak F, Lear SA, Anand SS. Cardiovascular Disease in South Asian Migrants. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:1139–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhopal RS. 2007. Ethnicity, race, and health in multicultural societies. 1st edit. Oxford University Press (Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP, United Kingdom); [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fellows IW, Freeman JG, Holmes GK. Crohn’s disease in the city of Derby, 1951-1985. Gut. 1990;31:1262–1265. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.11.1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinsk V, Lemberg DA, Grewal K, Barker CC, Schreiber RA, Jacobson K. Inflammatory bowel disease in the South Asian pediatric population of British Columbia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1077–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benchimol EI, Mack DR, Guttmann A, Nguyen GC, To T, Mojaverian N, Quach P, Manuel DG. Inflammatory bowel disease in immigrants to Canada and their children: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:553–563. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jayanthi V, Probert CS, Pollock DJ, Baithun SI, Rampton DS, Mayberry JF. Low incidence of ulcerative colitis and proctitis in Bangladeshi migrants in Britain. Digestion. 1992;52:34–42. doi: 10.1159/000200936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr I, Mayberry JF. The effects of migration on ulcerative colitis: a three-year prospective study among Europeans and first- and second- generation South Asians in Leicester (1991-1994) Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2918–2922. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Probert CS, Jayanthi V, Mayberry JF. Inflammatory bowel disease in Indian migrants in Fiji. Digestion. 1991;50:82–84. doi: 10.1159/000200743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayanthi V, Probert CS, Pinder D, Wicks AC, Mayberry JF. Epidemiology of Crohn’s disease in Indian migrants and the indigenous population in Leicestershire. Q J Med. 1992;82:125–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Probert CS, Jayanthi V, Hughes AO, Thompson JR, Wicks AC, Mayberry JF. Prevalence and family risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: an epidemiological study among Europeans and south Asians in Leicestershire. Gut. 1993;34:1547–1551. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.11.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurata JH, Kantor-Fish S, Frankl H, Godby P, Vadheim CM. Crohn’s disease among ethnic groups in a large health maintenance organization. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1940–1948. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90317-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang YR, Loftus EV Jr, Cangemi JR, Picco MF. Racial/Ethnic and regional differences in the prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Digestion. 2013;88:20–25. doi: 10.1159/000350759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee YM, Fock K, See SJ, Ng TM, Khor C, Teo EK. Racial differences in the prevalence of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in Singapore. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:622–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li BH, Guan X, Vittinghoff E, Gupta N. Comparison of the presentation and course of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in South Asians with Whites: a single center study in the United States. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1211–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cross RK, Jung C, Wasan S, Joshi G, Sawyer R, Roghmann MC. Racial differences in disease phenotypes in patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:192–198. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000217767.98389.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen GC, Torres EA, Regueiro M, Bromfield G, Bitton A, Stempak J, Dassopoulos T, Schumm P, Gregory FJ, Griffiths AM, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease characteristics among African Americans, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic Whites: characterization of a large North American cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1012–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eidelwein AP, Thompson R, Fiorino K, Abadom V, Oliva-Hemker M. Disease presentation and clinical course in black and white children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:555–560. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3180335bb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hattar LN, Abraham BP, Malaty HM, Smith EO, Ferry GD. Inflammatory bowel disease characteristics in Hispanic children in Texas. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:546–554. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghazi LJ, Lydecker AD, Patil SA, Rustgi A, Cross RK, Flasar MH. Racial differences in disease activity and quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2508–2513. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Damas OM, Jahann DA, Reznik R, McCauley JL, Tamariz L, Deshpande AR, Abreu MT, Sussman DA. Phenotypic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease differ between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites: results of a large cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:231–239. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kugathasan S, Judd RH, Hoffmann RG, Heikenen J, Telega G, Khan F, Weisdorf-Schindele S, San Pablo W Jr, Perrault J, Park R, Yaffe M, Brown C, Rivera-Bennett MT, Halabi I, Martinez A, Blank E, Werlin SL, Rudolph CD, Binion DG; Wisconsin Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Alliance. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of children with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease in Wisconsin: a statewide population-based study. J Pediatr. 2003;143:525–531. doi: 10.1067/s0022-3476(03)00444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malaty HM, Hou JK, Thirumurthi S. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease among an indigent multi-ethnic population in the United States. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2010;3:165–170. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S14586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adler J, Dong S, Eder SJ, Dombkowski KJ; ImproveCareNow Pediatric IBD Learning Health System. Perianal Crohn Disease in a Large Multicenter Pediatric Collaborative. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:e117–e124. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basu D, Lopez I, Kulkarni A, Sellin JH. Impact of race and ethnicity on inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2254–2261. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore L, Gaffney K, Lopez R, Shen B. Comparison of the natural history of ulcerative colitis in African Americans and non-Hispanic Caucasians: a historical cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:743–749. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flasar MH, Quezada S, Bijpuria P, Cross RK. Racial differences in disease extent and severity in patients with ulcerative colitis: a retrospective cohort study. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2754–2760. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker DG, Williams HR, Kane SP, Mawdsley JE, Arnold J, McNeil I, Thomas HJ, Teare JP, Hart AL, Pitcher MC, et al. Differences in inflammatory bowel disease phenotype between South Asians and Northern Europeans living in North West London, UK. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1281–1289. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodhand JR, Kamperidis N, Joshi NM, Wahed M, Koodun Y, Cantor EJ, Croft NM, Langmead FL, Lindsay JO, Rampton DS. The phenotype and course of inflammatory bowel disease in UK patients of Bangladeshi descent. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:929–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rashid ST, Bharucha S, Jamallulail SI, Banait GS, Kemp K, Makin A, Newman WG. Inflammatory bowel disease in the South Asian population of Northwest England. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:242–243; author reply 243-244. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01562_3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carroll MW, Hamilton Z, Gill H, Simkin J, Smyth M, Espinosa V, Bressler B, Jacobson K. Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Among South Asians Living in British Columbia, Canada: A Distinct Clinical Phenotype. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:387–396. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hilmi I, Singh R, Ganesananthan S, Yatim I, Radzi M, Chua AB, Tan HJ, Huang S, Chin KS, Menon J, et al. Demography and clinical course of ulcerative colitis in a multiracial Asian population: a nationwide study from Malaysia. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2008.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sofia MA, Rubin DT, Hou N, Pekow J. Clinical presentation and disease course of inflammatory bowel disease differs by race in a large tertiary care hospital. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2228–2235. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3160-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Misra R, Askari A, Faiz O, Arebi N. Colectomy Rates for Ulcerative Colitis Differ between Ethnic Groups: Results from a 15-Year Nationwide Cohort Study. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:8723949. doi: 10.1155/2016/8723949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Juyal G, Negi S, Sood A, Gupta A, Prasad P, Senapati S, Zaneveld J, Singh S, Midha V, van Sommeren S, et al. Genome-wide association scan in north Indians reveals three novel HLA-independent risk loci for ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2015;64:571–579. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brant SR, Okou DT, Simpson CL, Cutler DJ, Haritunians T, Bradfield JP, Chopra P, Prince J, Begum F, Kumar A, et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies African-Specific Susceptibility Loci in African Americans With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:206–217.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moshkovska T, Stone MA, Clatworthy J, Smith RM, Bankart J, Baker R, Wang J, Horne R, Mayberry JF. An investigation of medication adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis, using self-report and urinary drug excretion measurements. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:1118–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sprotson K, Mindell J. 2004. The health of minority ethnic groups - Summary of key findings. Available from: http://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB01170. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burisch J, Pedersen N, Čuković-Čavka S, Brinar M, Kaimakliotis I, Duricova D, Shonová O, Vind I, Avnstrøm S, Thorsgaard N, et al. East-West gradient in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: the ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. Gut. 2014;63:588–597. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Misra R, Burisch J, Haji S, Salupere R, Ellul P, Ramirez V, D’Inca R, Munkholm PAN. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation. Barcelona: 2017. Impact of migration on IBD incidence in 8 European populations: results from Epicom 2010 inception cohort study. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hammer T, Lophaven SN, Nielsen KR, von Euler-Chelpin M, Weihe P, Munkholm P, Burisch J, Lynge E. Inflammatory bowel diseases in Faroese-born Danish residents and their offspring: further evidence of the dominant role of environmental factors in IBD development. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:1107–1114. doi: 10.1111/apt.13975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Agus A, Denizot J, Thévenot J, Martinez-Medina M, Massier S, Sauvanet P, Bernalier-Donadille A, Denis S, Hofman P, Bonnet R, et al. Western diet induces a shift in microbiota composition enhancing susceptibility to Adherent-Invasive E. coli infection and intestinal inflammation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19032. doi: 10.1038/srep19032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Limdi JK, Aggarwal D, McLaughlin JT. Dietary Practices and Beliefs in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:164–170. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prideaux L, Kang S, Wagner J, Buckley M, Mahar JE, De Cruz P, Wen Z, Chen L, Xia B, van Langenberg DR, et al. Impact of ethnicity, geography, and disease on the microbiota in health and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2906–2918. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000435759.05577.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rehman A, Rausch P, Wang J, Skieceviciene J, Kiudelis G, Bhagalia K, Amarapurkar D, Kupcinskas L, Schreiber S, Rosenstiel P, et al. Geographical patterns of the standing and active human gut microbiome in health and IBD. Gut. 2016;65:238–248. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mar JS, LaMere BJ, Lin DL, Levan S, Nazareth M, Mahadevan U, Lynch S V. Disease Severity and Immune Activity Relate to Distinct Interkingdom Gut Microbiome States in Ethnically Distinct Ulcerative Colitis Patients. MBio. 2016;7:e01072–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01072-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gensollen T, Iyer SS, Kasper DL, Blumberg RS. How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science. 2016;352:539–544. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]