Abstract

The present study aimed to investigate the clinical characteristics of hemorrhagic moyamoya disease (MMD) in Jilin province in northeast China. A total of 212 cases of hemorrhagic MMD were consecutively enrolled from the First Hospital of Jilin University in Changchun, China between January 2011 and January 2015. The patients' general clinical data, including age and gender characteristics, history of previous illnesses, hemorrhage type and onset symptoms, Hunt-Hess classification at admission, imaging characteristics, association with aneurysms, treatments and prognosis, were recorded and analyzed using SPSS 19.0. The results demonstrated that i) patients with hemorrhagic MMD in Jilin province were 47.7±11.5 years of age; ii) hemorrhagic MMD was primarily characterized by subarachnoid hemorrhage; iii) a total of 51.9% of the hemorrhagic MMD cases involved a unilateral artery; iv) a total of 24.1% of the hemorrhagic MMD cases were accompanied by anterior choroid artery and/or posterior communicating artery expansion; and v) following conservative or surgical treatment, patients with a prognostic Glasgow Outcome Scale score of 5 accounted for 65.6% of the study population. Therefore, the present study identified characteristics of MMD in Jilin province in northeast China. These results may improve understanding of the epidemiology of MMD in China, which at present remains not well established. Although the results are representative only of Jilin province in China, the study demonstrated high consistency with other studies, and thus may indirectly contribute to general understanding of hemorrhagic MMD etiology.

Keywords: Jilin province, hemorrhagic moyamoya disease, aneurysm, subarachnoid hemorrhage

Introduction

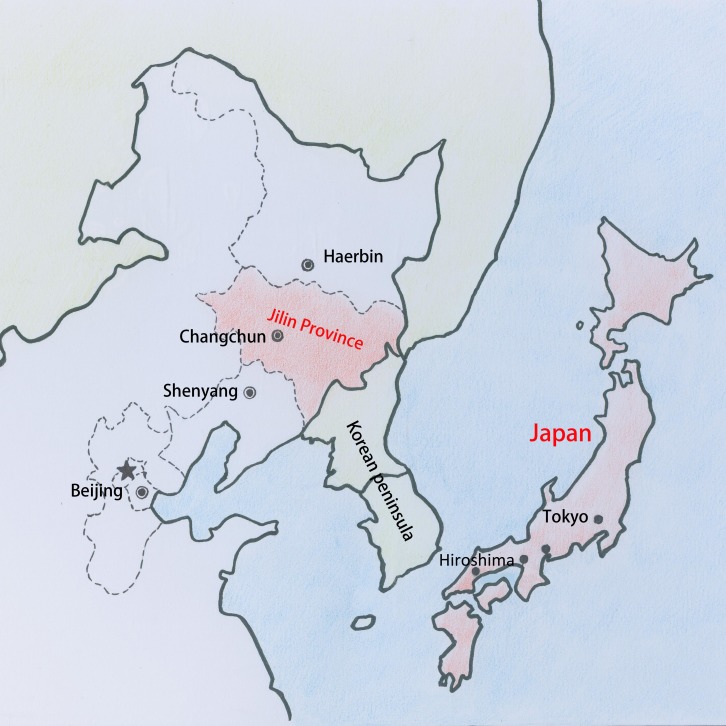

Moyamoya disease (MMD) is a type of chronic vascular occlusive disease of unknown etiology that was first identified in Japan in 1965 (1), though has since been established to have a global distribution (2). MMD is characterized by ischemia and hemorrhage. Cases in children are more often characterized by ischemia, whereas more than half of adult MMD patients exhibit various types of cerebral hemorrhages (3–5). China and the surrounding Asian countries are areas of high prevalence of MMD (6–8). Although previous studies have investigated MMD in Japan and South Korea, few clinical epidemiological studies on MMD have been conducted in China, with even fewer studies on hemorrhagic MMD (9–11). Therefore, it is warranted to study hemorrhagic MMD in Jilin, as a province in northeast China adjacent to Japan (Fig. 1). The present study consecutively enrolled hemorrhagic MMD cases from the Neurosurgery Department at the First Hospital of Jilin University (Changchun, China). The First Hospital of Jilin University is currently the largest medical institution in Jilin province, and MMD cases admitted to the Neurosurgery Department account for approximately 80% of the confirmed MMD cases in Jilin province (12,13); therefore, the present study may be considered as representative. Jilin province is located in the middle of northeast China, at 122–131° north and 41–46° east. It has a temperate monsoon climate, with typical continental characteristics, namely megathermal wet summers and dry cold winters (14,15). Hemorrhagic MMD in this area may have certain clinical characteristics that differ from those in neighboring Japan and Korea. The present study systemically reviewed the clinical data of patients with hemorrhagic MMD admitted to the Neurosurgery Department of the First Hospital of Jilin University between January 2009 and January 2014. This aimed to summarize the clinical epidemiological characteristics of hemorrhagic MMD in Jilin province, to ultimately provide information on key epidemiological characteristics for future research.

Figure 1.

Map displaying the geographical proximity of Jilin province to Japan.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

A total of 212 patients with hemorrhagic MMD were consecutively enrolled from the Neurosurgery Department of the First Hospital of Jilin University between January 2011 and January 2015. The inclusion criteria were patients definitively diagnosed with cerebral hemorrhage using head computed tomography (CT) and confirmed to have MMD using CT angiography (CTA) and/or digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Patients with comorbidities and/or a medical history of other conditions were included. Following diagnosis, the patients were administered appropriate treatments. Cases with incomplete information on any relevant data collected for the study were excluded. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Jilin University, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients allowing the use and publication of their data in the study.

Data collection methods

The MMD cases were screened on the medical records management system of the First Hospital of Jilin University in chronological order according to the inclusion criteria, and the patients' gender, age, history of previous illnesses, onset time, onset symptoms, hemorrhage type, Hunt-Hess Scale grading (with minor revision in 2001) (16), imaging results, treatments and prognostic Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) (17,18) score were recorded.

Statistical methods

SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analyses. χ2 tests were used for the enumeration data, with an inspection level of α=0.05, and P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Age and gender characteristics of the hemorrhagic MMD patients

In total, 212 patients ranging in age from 14 to 84 ears and with an average age of 47.7±11.5 years were included in the study. There were 101 female patients and 111 male patients, with a gender ratio of 1:1.1.

History of previous illnesses

Among the 212 patients, 13 (6.1%) had a history of cerebral ischemia, 32 (15.1%) had a history of cerebral hemorrhage, 50 (23.6%) had a history of hypertension and 7 (3.3%) had a history of diabetes.

Hemorrhage types and onset symptoms

The hemorrhage types of the 212 patients were as follows: Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH; 116 cases, 54.7%), intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH; 25 cases, 11.8%) and intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH; 71 cases, 33.5%).

The onset symptoms of the 212 patients were as follows: Headache associated with nausea and vomiting (130 cases, 61.3%), unconsciousness (43 cases, 20.3%), limb paralysis and/or aphasia (23 cases, 10.8%), transient unconsciousness and subsequent headache, nausea and vomiting (9 cases, 4.3%), dizziness (6 cases, 2.8%) and oculomotor nerve paralysis (1 case, 0.5%).

Hunt-Hess classification at admission

Among the 212 patients, Hunt-Huss grade I was observed in 111 (52.4%), grade II in 23 (10.8%), grade III in 51 (24.1%), grade IV in 24 (11.3%) and grade V in 3 (1.4%).

Imaging characteristics

Among the 212 patients, 122 (57.5%) underwent CTA only, 50 (23.6%) underwent DSA only, and 40 (18.9%) underwent CTA and DSA.

Hemisphere involvement

MMD involving a unilateral artery was identified in 110 cases (51.9%) and MMD involving bilateral arteries was identified in 102 cases (48.1%).

Association with aneurysms

Among the 212 cases, 74 (34.9%) were accompanied by aneurysms. Among the 74 cases involving aneurysms, 57 (77.0%) involved anterior circulation aneurysms, which included anterior communicating aneurysms (27/74, 36.5%), distal anterior artery aneurysms (2/74, 2.7%), posterior communicating aneurysms (9/74, 12.1%), middle cerebral artery aneurysms (8/74, 10.8%), ophthalmic aneurysms (5/74, 6.8%), choroid aneurysms (1/74, 1.4%) and perforator aneurysms of the middle cerebral artery distribution area (5/74, 6.8%). The remaining 17 cases (17/74, 23.0%) involved posterior circulation aneurysms, including posterior cerebral aneurysms (9/74, 12.2%), basilar artery apex aneurysms (6/74, 8.1%), superior cerebellar artery aneurysms (1/74, 1.4%), and anterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysms (1/74, 1.4%).

Among the 212 cases, expansion of the anterior choroid artery (AChA) and/or the posterior communicating artery (PComA) was observed in 51 cases (24.1%).

Treatments and prognosis

Of the 212 patients, 144 (67.9%) underwent conservative treatments, while 68 (32.1%) underwent surgical treatments.

Among the 68 patients who underwent surgical treatments, aneurysm embolization was performed in 21 cases (30.9%), aneurysm clipping in 18 cases (26.5%), removal of the hematoma plus a decompressive craniectomy in 10 cases (14.7%), lateral ventricle drainage in 9 cases (13.2%), aneurysm clipping plus roofing of the temporal muscle (encephalo-myo-synangiosis) in 8 cases (11.8%) and simple encephalo-myo-synangiosis in 2 cases (2.9%).

Among the 212 cases, GOS scores of 5, 4, 3, 2 and 1 were observed in 139 (65.6%), 21 (9.9%), 28 (13.2%), 13 (6.1%) and 11 (5.2%) cases, respectively.

Effect of an association with aneurysm on hemorrhage type and prognosis

The 212 cases were divided into aneurysm and non-aneurysm groups according to the presence of an aneurysm. The results of a χ2 test indicated that there was a statistically significant difference (P<0.05) between the two groups regarding the distributions of the hemorrhage types and prognostic GOS scores.

According to the results of the cross table, in the aneurysm group, the highest proportion of patients had SAH (86.5%), followed by ICH (10.8%) and IVH (2.7%). In the non-aneurysm group, the majority of the patients had ICH (45.6%), followed by SAH (37.7%) and IVH (16.7%). The χ2 test (χ2=46.394 and P<0.05) suggested these results were statistically significant (Table I).

Table I.

Effect of combined aneurysm on hemorrhage type in moyamoya disease.

| Hemorrhage type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | SAH | IVH | ICH | Total |

| Combined with an aneurysm | ||||

| N | ||||

| Count | 52 | 23 | 63 | 138 |

| Percentage (%) | 37.7 | 16.7 | 45.6 | 100.0 |

| Y | ||||

| Count | 64 | 2 | 8 | 74 |

| Percentage (%) | 86.5 | 2.7 | 10.8 | 100.0 |

| Total | ||||

| Count | 116 | 25 | 71 | 212 |

| Percentage(%) | 54.7 | 11.8 | 33.5 | 100.0 |

χ2=46.394, P<0.05. SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; N, no; Y, yes.

A total of 86.5% of the patients in the aneurysm group had GOS scores of 5 or 4, which was higher than that in the non-aneurysm group (69.6%), indicating good prognosis in these patients. A χ2 test (χ2=14.589 and P<0.05) suggested that these results were statistically significant (Table II).

Table II.

Effect of the combination of moyamoya disease and aneurysm on prognostic GOS score.

| Prognostic GOS score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total |

| Combined with an aneurysm | ||||||

| N | ||||||

| Count | 9 | 10 | 23 | 18 | 78 | 138 |

| Percentage (%) | 6.5 | 7.2 | 16.7 | 13.1 | 56.5 | 100.0 |

| Y | ||||||

| Count | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 61 | 74 |

| Percentage (%) | 2.7 | 4.0 | 6.8 | 4.1 | 82.4 | 100.0 |

| Total | ||||||

| Count | 11 | 13 | 28 | 21 | 139 | 212 |

| Percentage (%) | 5.2 | 6.1 | 13.2 | 9.9 | 65.6 | 100.0 |

χ2=14.589, P<0.05. GOS, Glasgow Outcome Scale; N, no; Y, yes.

Effect of the involvement of unilateral or bilateral arteries on aneurysm site

In total, 74 patients presented with aneurysms and were further divided into a bilateral involvement or unilateral involvement group according to the imaging data. A χ2 test comparing the unilateral and bilateral distribution between the two groups indicated statistically significant differences (P<0.05).

Among the MMD cases involving bilateral arteries, 63.3% involved anterior circulation aneurysms and 36.7% involved posterior circulation aneurysms, whereas among the MMD cases involving unilateral arteries, 86.4% involved anterior circulation aneurysms and 13.6% involved posterior circulation aneurysms. The χ2 test (χ2=5.347 and P<0.05) suggested that these results were statistically significant (Table III). Thus, patients with MMD involving bilateral arteries were more likely to develop posterior circulation aneurysms than patients with MMD involving unilateral arteries; however, the percentage of patients with anterior circulation aneurysms was markedly high in both groups.

Table III.

Effect of unilateral and bilateral moyamoya disease on aneurysm site.

| Aneurysm | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Anterior circulation | Posterior circulation | Total |

| Side | |||

| Unilateral | |||

| Count | 38 | 6 | 44 |

| Percentage (%) | 86.4 | 13.6 | 100.0 |

| Bilateral | |||

| Count | 19 | 11 | 30 |

| Percentage (%) | 63.3 | 36.7 | 100.0 |

| Total | |||

| Count | 57 | 17 | 74 |

| Percentage (%) | 77.0 | 23.0 | 100.0 |

χ2=5.347, P<0.05.

Effect of an expansion of the AChA and/or PComA on hemorrhage type

The 212 cases were further divided into two groups according to the presence or absence of AChA and/or PComA expansion based on the imaging data. A χ2 test comparing the hemorrhagic-type distribution between the groups indicated a statistically significant difference (P<0.05).

The statistical results demonstrated that 51 patients in the expansion group presented with AChA and/or PComA expansion, with the incidence rates of ICH, IVH and SAH being 41.2, 35.3 and 23.5%, respectively. In the 161 patients in the non-expansion group who did not present with AChA and/or PComA expansion, the incidence rates of SAH, ICH and IVH were 64.6, 31.1% and 4.3%, respectively. The results of the χ2 test (χ2=5.347 and P<0.05) suggested a statistically significant difference in the distribution of hemorrhage types between the two groups (Table IV).

Table IV.

Effect of AChA and/or PComA expansion on hemorrhage type.

| Hemorrhage type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | SAH | IVH | ICH | Total |

| AChA and/or PComA expansion | ||||

| N | ||||

| Count | 104 | 7 | 50 | 161 |

| Percentage (%) | 64.6 | 4.3 | 31.1 | 100.0 |

| Y | ||||

| Count | 12 | 18 | 21 | 51 |

| Percentage (%) | 23.5 | 35.3 | 41.2 | 100.0 |

| Total | ||||

| Count | 116 | 25 | 71 | 212 |

| Percentage(%) | 54.7 | 11.8 | 33.5 | 100.0 |

χ2=5.347, P<0.05. AChA, anterior choroid artery; PComA, posterior communicating artery; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; N, no; Y, yes.

Association of hemorrhage history with prognostic scores

The 212 patients were further divided into two groups according to hemorrhage history. A total of 32 patients had a history of hemorrhage. A χ2 test comparing GOS score distribution between the two groups indicated statistically significant results (P<0.05).

Among the 212 patients, 32 patients had a history of hemorrhage, with GOS scores of 5 or 4 accounting for 43.8% of the patients. In the 180 patients with no history of hemorrhage, cases with GOS scores of 5 or 4 accounted for 81.1% of the patients. The χ2 test (χ2=32.195 and P<0.05) suggested that the prognosis of patients with a history of hemorrhage was poorer than that of patients without a history of hemorrhage (Table V).

Table V.

Effect of a history of hemorrhage on prognostic GOS score.

| Prognostic GOS score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total |

| Hemorrhage history | ||||||

| N | ||||||

| Count | 7 | 8 | 19 | 14 | 132 | 180 |

| Percentage (%) | 3.9 | 4.4 | 10.6 | 7.8 | 73.3 | 100.0 |

| Y | ||||||

| Count | 4 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 32 |

| Percentage (%) | 12.5 | 15.6 | 28.1 | 21.9 | 21.9 | 100.0 |

| Total | ||||||

| Count | 11 | 13 | 28 | 21 | 139 | 212 |

| Percentage (%) | 5.2 | 6.1 | 13.2 | 9.9 | 65.6 | 100.0 |

χ2=32.195, P<0.05. GOS, GlasgowOutcome Scale; N, no; Y, yes.

Discussion

MMD is a rare cerebrovascular disease of unknown etiology, characterized by progressive intracranial internal carotid artery stenosis and occlusion (8). It was first identified in Japan in 1965, after which Suzuki and Takaku termed the condition moyamoya disease, as the terminology still used to date (19). Previous results have suggested that the occurrence and development of MMD are associated with genetic and immune factors (20). The 212 patients with hemorrhagic MMD enrolled in the current study did not have an obvious history of familial heredity, which may be due to the description of illness history and/or lack of knowledge on MMD among the patients' families. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that MMD occurs more frequently in Asian countries (21–23); the prevalence rate was 3.92/100,000 in China in 2010 (24), 18.1/100,000 in Korea in 2013 (25), and estimated to be as high as 50.7/100,000 in Japan in 2016 (26,27). Furthermore, the prevalence of MMD tends to be twice as high in females as in males (28). The gender ratio of hemorrhagic MMD cases included in the present study was approximately 1:1, which did not indicate a gender difference. This finding may be due to the small sample size and/or due to the inclusion of only hemorrhagic MMD cases. Nevertheless, this result suggests that male MMD patients may be more prone to hemorrhagic lesions. Previous studies have reported that the age of onset of MMD exhibits a bimodal distribution, with the first peak occurring at 5–10 years of age and the second peak occurring at 40–50 years of age (29,30). The average age of the patients in the current study was 47.7±11.5 years, which is consistent with the timing of the second peak. As few children were enrolled, the first age peak was not observed; this may be attributed to the fact that MMD in children is mainly characterized by ischemia, whereas in adults, hemorrhagic MMD accounts for more than half of all MMD cases (5).

Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with MMD combined with aneurysms were more vulnerable to hemorrhage, and 3–15% of MMD cases were accompanied by an aneurysm (31,32). However, hemorrhage caused by MMD includes not only the rupture hemorrhage of the merged aneurysm but also the rupture hemorrhage of the pseudoaneurysm or small cystic aneurysm formed by the expanded moyamoya-like vessels or terminal arteries (33). Aneurysms of the main trunk primarily cause SAH (34), and hemorrhage caused by small aneurysms of moyamoya-like vessels or terminal arteries are prioritized over ICH, mainly of the periventricular type, and/or IVH (35,36). Among the 212 patients with hemorrhagic MMD included in the current study, SAH was the major hemorrhagic type in the MMD patients with an aneurysm, whereas ICH was the major hemorrhagic type in the patients without aneurysms, which is consistent with the results of previous reports (37,38). Previous studies have also identified that MMD combined with aneurysms may be associated with cerebral hemodynamic changes, and that aneurysm is often observed in the anterior communicating artery of unilateral MMD patients (39), but not in the posterior circulation system of bilateral MMD patients (40). Common non-hemorrhage symptoms of MMD patients include headaches, mild hemiparesis, sensory abnormalities or dysarthria, whereas visual symptoms, cognitive symptoms and epilepsy are rare (26). In the present study, the patients with hemorrhagic MMD mainly experienced headaches, altered consciousness, nausea and vomiting, which is consistent with the symptoms of SAH and ICH (41). The clinical manifestations are associated with the type, severity and position of the hemorrhage (42).

The present study also evaluated the relationship between MMD accompanied by aneurysms and the prognostic GOS scores. The results suggested that a higher proportion of MMD patients with aneurysms compared with those without aneurysms had mild disability (namely GOS scores above 4). This finding indicated that if the patient survived following rupture of an aneurysm of a major blood vessel, then aneurysm treatment may improve prognosis. For patients with hemorrhagic MMD, endovascular interventional treatment may be used to treat patients with major artery aneurysms (13,43). Aneurysms can also be clipped directly, though craniotomy clipping may destroy the collateral circulation of the aneurysm, thus causing cerebral ischemia (39). However, for hemorrhage due to rupture of a pseudoaneurysm or small cystic aneurysm formed by expanded moyamoya-like vessels or terminal arteries, a craniotomy or interventional treatment has difficulty in achieving satisfactory results; therefore, cerebrovascular bypass surgery is often adopted with the parent artery sacrificed (8,44). Furthermore, indirect bypass treatment generally requires more than 3 months to develop collateral circulation (45). In the current study, vascular interventions or clipping achieved more ideal clinical effects in MMD patients with aneurysms, whereas for patients with ICH or IVH, craniotomies or vascular interventions were not effective, probably due to the cerebral hematoma destroying the functional areas, which may be a reason for the low prognostic scores in these patients.

Previous reports also state that hemorrhagic MMD combined with AChA and/or PComA expansion may be the major cause of hemorrhage (32,46,47). Morioka et al (48) examined 107 cases of MMD with AChA and/or PComA expansion (including 70 cases of the ischemic type and 37 cases of the hemorrhagic type) in 2003 and observed that AChA and/or PComA expansion was significantly associated with hemorrhagic MMD. Although the present study did not include ischemic MMD patients, among the 212 patients, 24.1% of the hemorrhagic MMD patients exhibited AChA and/or PComA expansion. In addition, a previous study also reported that AChA and/or PComA expansion was an independent risk factor for IVH (49). Similarly, in the current study, the proportion of ICH was higher in the patients with AChA and/or PComA expansion compared with the patients without AChA and/or PComA expansion.

Previous studies have also demonstrated that a notable proportion of adult patients exhibited minor hemorrhage with or without symptoms, which significantly predicted the deterioration of MMD and increased the hemorrhage risk (3,50). In the current study, the rate of mild disability, namely prognostic GOS scores of 5 or 4, was markedly lower in the MMD patients with a history of hemorrhage than in the MMD patients without a history of hemorrhage, which may be due to the MMD patients with a history of hemorrhage undergoing repeated progression, and thus demonstrating rapid progression that resulted in irreversible damage. Therefore, for patients with confirmed MMD, a positive follow-up should be conducted even if the patient does not present with serious clinical symptoms, and intracranial vascular changes should be closely monitored.

In conclusion, the present analyses of the clinical characteristics of MMD in Jilin province (northeast China) indicated that the characteristics of MMD are distinct in this area. The average age of onset was 47.7±11.5 years, and the gender ratio was approximately to 1:1. Furthermore, approximately 1/3 of the hemorrhagic MMD cases were accompanied by aneurysm, and the most common hemorrhagic type was SAH. The prognosis of the patients with an aneurysm was more favorable compared with that of the hemorrhagic MMD patients without an aneurysm. The ratio of ICH and IVH was also higher in the MMD patients with AChA and/or PComA expansion, and the prognostic GOS scores were poorer in the patients with a history of hemorrhage. The patients with bilateral involvement were also more likely to develop posterior circulation aneurysms than those with unilateral involvement. In China, the epidemiological study of MMD is rare, and thus the present findings may improve understanding of the epidemiology of MMD in this region.

References

- 1.Hemangiomatous malformation of the bilateral internal carotid arteries at the base of brain. No To Shinkei. 1965;17:750–756. (In Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goto Y, Yonekawa Y. Worldwide distribution of moyamoya disease. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1992;32:883–886. doi: 10.2176/nmc.32.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jo KI, Kim MS, Yeon JY, Kim JS, Hong SC. Recurrent Bleeding in Hemorrhagic Moyamoya Disease: Prognostic Implications of the Perfusion Status. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2016;59:117–121. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2016.59.2.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuroda S, Houkin K. Moyamoya disease: Current concepts and future perspectives. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1056–1066. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piao J, Wu W, Yang Z, Yu J. Research Progress of Moyamoya Disease in Children. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12:566–575. doi: 10.7150/ijms.11719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuriyama S, Kusaka Y, Fujimura M, Wakai K, Tamakoshi A, Hashimoto S, Tsuji I, Inaba Y, Yoshimoto T. Prevalence and clinicoepidemiological features of moyamoya disease in Japan: Findings from a nationwide epidemiological survey. Stroke. 2008;39:42–47. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hung CC, Tu YK, Su CF, Lin LS, Shih CJ. Epidemiological study of moyamoya disease in Taiwan. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1997;99(Suppl 2):S23–S25. doi: 10.1016/S0303-8467(97)82182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu J, Shi L, Guo Y, Xu B, Xu K. Progress on Complications of Direct Bypass for Moyamoya Disease. Int J Med Sci. 2016;13:578–587. doi: 10.7150/ijms.15390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikezaki K, Han DH, Kawano T, Kinukawa N, Fukui M. A clinical comparison of definite moyamoya disease between South Korea and Japan. Stroke. 1997;28:2513–2517. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.28.12.2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayashi K, Horie N, Izumo T, Nagata I. A nationwide survey on unilateral moyamoya disease in Japan. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;124:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikezaki K, Han DH, Kawano T, Inamura T, Fukui M. Epidemiological survey of moyamoya disease in Korea. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1997;99(Suppl 2):S6–S10. doi: 10.1016/S0303-8467(97)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao M, Zhang H, Liu Q, Zhang S, Hu L, Deng F. Clinical and experimental pathology of Moyamoya disease. Chin Med J (Engl) 2003;116:1845–1849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu JL, Wang HL, Xu K, Li Y, Luo Q. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms associated with moyamoya disease or moyamoya syndrome. Interv Neuroradiol. 2010;16:240–248. doi: 10.1177/159101991001600302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li C, Yan Z, Zhang L, Li Y. Research and implementation of good agricultural practice for traditional Chinese medicinal materials in Jilin Province, China. J Ginseng Res. 2014;38:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J, Yang J, Guan G, Liu A, Wang B, Luo J, Yin H. Molecular detection and identification of piroplasms in sika deer (Cervus nippon) from Jilin Province, China. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:156. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1435-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stranjalis G, Sakas DE. A minor revision of Hunt and Hess scale. Stroke. 2001;32:2208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMillan T, Wilson L, Ponsford J, Levin H, Teasdale G, Bond M. The Glasgow Outcome Scale-40 years of application and refinement. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:477–485. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jennett B, Snoek J, Bond MR, Brooks N. Disability after severe head injury: Observations on the use of the Glasgow Outcome Scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1981;44:285–293. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.44.4.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki J, Takaku A. Cerebrovascular ‘moyamoya’ disease. Disease showing abnormal net-like vessels in base of brain. Arch Neurol. 1969;20:288–299. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1969.00480090076012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Achrol AS, Guzman R, Lee M, Steinberg GK. Pathophysiology and genetic factors in moyamoya disease. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;26:E4. doi: 10.3171/2009.1.FOCUS08302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen JB, Liu Y, Zhou LX, Sun H, He M, You C. Prevalence of autoimmune disease in moyamoya disease patients in Western Chinese population. J Neurol Sci. 2015;351:184–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn IM, Park DH, Hann HJ, Kim KH, Kim HJ, Ahn HS. Incidence, prevalence, and survival of moyamoya disease in Korea: A nationwide, population-based study. Stroke. 2014;45:1090–1095. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takamatsu Y, Higashimoto K, Maeda T, Kawashima M, Matsuo M, Abe T, Matsushima T, Soejima H. Differences in the Genotype Frequency of the RNF213 Variant in Patients with Familial Moyamoya Disease in Kyushu, Japan. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2017;57:607–611. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa.2017-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang S, Guo ZN, Shi M, Yang Y, Rao M. Etiology and pathogenesis of Moyamoya Disease: An update on disease prevalence. Int J Stroke. 2017;12:246–253. doi: 10.1177/1747493017694393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim T, Lee H, Bang JS, Kwon OK, Hwang G, Oh CW. Epidemiology of Moyamoya Disease in Korea: Based on National Health Insurance Service Data. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2015;57:390–395. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2015.57.6.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JS. Moyamoya Disease: Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis. J Stroke. 2016;18:2–11. doi: 10.5853/jos.2015.01627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hishikawa T, Sugiu K, Date I. Moyamoya Disease: A Review of Clinical Research. Acta Med Okayama. 2016;70:229–236. doi: 10.18926/AMO/54497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinloog R, Regli L, Rinkel GJ, Klijn CJ. Regional differences in incidence and patient characteristics of moyamoya disease: A systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:531–536. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoshino H, Izawa Y, Suzuki N. Research Committee on Moyamoya Disease: Epidemiological features of moyamoya disease in Japan. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2012;52:295–298. doi: 10.2176/nmc.52.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikezaki K, Fukui M, Inamura T, Kinukawa N, Wakai K, Ono Y. The current status of the treatment for hemorrhagic type moyamoya disease based on a 1995 nationwide survey in Japan. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1997;99(Suppl 2):S183–S186. doi: 10.1016/S0303-8467(97)00077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang L, Xu K, Zhang Y, Wang X, Yu J. Treatment strategies for aneurysms associated with moyamoya disease. Int J Med Sci. 2015;12:234–242. doi: 10.7150/ijms.10837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jang DK, Lee KS, Rha HK, Huh PW, Yang JH, Park IS, Ahn JG, Sung JH, Han YM. Clinical and angiographic features and stroke types in adult moyamoya disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:1124–1131. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhim JK, Cho YD, Jeon JP, Yoo DH, Cho WS, Kang HS, Kim JE, Han MH. Ruptured Aneurysms of Collateral Vessels in Adult Onset Moyamoya Disease with Hemorrhagic Presentation. Clin Neuroradiol. 2016 Dec 13; doi: 10.1007/s00062-016-0554-8. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aoki N, Mizutani H. Does moyamoya disease cause subarachnoid hemorrhage? Review of 54 cases with intracranial hemorrhage confirmed by computerized tomography. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:348–353. doi: 10.3171/jns.1984.60.2.0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuoka G, Kubota Y, Okada Y. Delayed cerebral ischemia associated with reversible cerebral vasoconstriction in a patient with Moyamoya disease with intraventricular hemorrhage: Case report. Neuroradiol J. 2015;28:322–324. doi: 10.1177/1971400915592553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu P, Liu AH, Han C, Chen C, Lv XL, Li DS, Ge HJ, Jin HW, Li YX, Duan L. Difference in Angiographic Characteristics Between Hemorrhagic And Nonhemorrhagic Hemispheres Associated with Hemorrhage Risk of Moyamoya Disease in Adults: A Self-Controlled Study. World Neurosurg. 2016;95:348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Funaki T, Takahashi JC, Houkin K, Kuroda S, Takeuchi S, Fujimura M, Tomata Y, Miyamoto S. on behalf of the JAM Trial Investigators: Angiographic features of hemorrhagic moyamoya disease with high recurrence risk: A supplementary analysis of the Japan Adult Moyamoya Trial. J Neurosurg. 2017;14:1–8. doi: 10.3171/2016.11.JNS161650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wan M, Duan L. Recent progress in hemorrhagic moyamoya disease. Br J Neurosurg. 2015;29:189–191. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2014.976177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu J, Yuan Y, Zhang D, Xu K. Moyamoya disease associated with arteriovenous malformation and anterior communicating artery aneurysm: A case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:267–271. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y, Dai D, Fang Y, Yang P, Huang Q, Zhao W, Xu Y, Liu J. Endovascular Treatment of Ruptured Large or Wide-Neck Basilar Tip Aneurysms Associated with Moyamoya Disease Using the Stent-Assisted Coil Technique. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:2229–2235. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wan M, Han C, Xian P, Yang WZ, Li DS, Duan L. Moyamoya disease presenting with subarachnoid hemorrhage: Clinical features and neuroimaging of a case series. Br J Neurosurg. 2015;29:804–810. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2015.1071327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujimura M, Mugikura S, Shimizu H, Tominaga T. Asymptomatic moyamoya disease subsequently manifesting as transient ischemic attack, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage in a short period: Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2010;50:316–319. doi: 10.2176/nmc.50.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wada K, Hattori K, Araki Y, Noda T, Maki H, Oyama H, Kito A, Wakabayashi T. A case of moyamoya disease with a subarachnoid hemorrhage treated with endovascular technique. No Shinkei Geka. 2014;42:1027–1033. doi: 10.11477/mf.1436200026. (In Japanese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao WG, Luo Q, Jia JB, Yu JL. Cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome after revascularization surgery in patients with moyamoya disease. Br J Neurosurg. 2013;27:321–325. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2012.757294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang L, Qian C, Yu X, Fu X, Chen T, Gu C, Chen J, Chen G. Indirect Bypass Surgery May Be More Beneficial for Symptomatic Patients with Moyamoya Disease at Early Suzuki Stage. World Neurosurg. 2016;95:304–308. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qi L, Jinlu Y. Moyamoya disease with posterior communicating artery aneurysm: A case report. Turk Neurosurg. 2013;23:546–550. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.5668-11.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang S, Yu JL, Wang HL, Wang B, Luo Q. Endovascular embolization of distal anterior choroidal artery aneurysms associated with moyamoya disease. A report of two cases and a literature review. Interv Neuroradiol. 2010;16:433–441. doi: 10.1177/159101991001600410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morioka M, Hamada J, Kawano T, Todaka T, Yano S, Kai Y, Ushio Y. Angiographic dilatation and branch extension of the anterior choroidal and posterior communicating arteries are predictors of hemorrhage in adult moyamoya patients. Stroke. 2003;34:90–95. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000047120.67507.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nah HW, Kwon SU, Kang DW, Ahn JS, Kwun BD, Kim JS. Moyamoya disease-related versus primary intracerebral hemorrhage: [corrected] location and outcomes are different. Stroke. 2012;43:1947–1950. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.654004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu J, Yuan Y, Li W, Xu K. Moyamoya disease manifested as multiple simultaneous intracerebral hemorrhages: A case report and literature review. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:1440–1444. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]