Abstract

Prochlorococcus is a globally important marine cyanobacterium that lacks the gene catalase and relies on ‘helper’ bacteria such as Alteromonas to remove reactive oxygen species. Increasing atmospheric CO2 decreases the need for carbon concentrating mechanisms and photorespiration in phytoplankton, potentially altering their metabolism and microbial interactions even when carbon is not limiting growth. Here, Prochlorococcus (VOL4, MIT9312) was co-cultured with Alteromonas (strain EZ55) under ambient (400 p.p.m.) and elevated CO2 (800 p.p.m.). Under elevated CO2, Prochlorococcus had a significantly longer lag phase and greater apparent die-offs after transfers suggesting an increase in oxidative stress. Whole-transcriptome analysis of Prochlorococcus revealed decreased expression of the carbon fixation operon, including carboxysome subunits, corresponding with significantly fewer carboxysome structures observed by electron microscopy. Prochlorococcus co-culture responsive gene 1 had significantly increased expression in elevated CO2, potentially indicating a shift in the microbial interaction. Transcriptome analysis of Alteromonas in co-culture with Prochlorococcus revealed decreased expression of the catalase gene, known to be critical in relieving oxidative stress in Prochlorococcus by removing hydrogen peroxide. The decrease in catalase gene expression was corroborated by a significant ~6-fold decrease in removal rates of hydrogen peroxide from co-cultures. These data suggest Prochlorococcus may be more vulnerable to oxidative stress under elevated CO2 in part from a decrease in ecosystem services provided by heterotrophs like Alteromonas. This work highlights the importance of considering microbial interactions in the context of a changing ocean.

Introduction

Prochlorococcus is the smallest and most abundant photosynthetic organism on the planet, having a crucial role in the marine carbon cycle, particularly in tropical and subtropical marine ecosystems (Buitenhuis et al., 2012; Biller et al., 2015). Atmospheric carbon dioxide is projected to double over this century, causing a decrease in pH and an increase in dissolved CO2 in the ocean (Ciais and Sabine, 2013). Modeling studies suggest that the contribution of Prochlorococcus to the marine carbon cycle may be more negatively affected by the increase in carbon availability compared with other climate change impacts (Dutkiewicz et al., 2015). To make better projections of the distribution and production of this globally important cyanobacterium, we need a mechanistic understanding of how CO2 impacts Prochlorococcus growth, cellular processes and its interactions with other microbes.

Field experiments with natural communities of picoplankton from the subtropical North Atlantic under elevated CO2 found a short-term increase in 14C carbon fixation but no increase in net growth of Prochlorococcus over a few days (Lomas et al., 2012), highlighting the need for simplified community experiments with the ability to acclimate strains in the lab for longer periods of time. Previous experiments with the high light I ecotype of Prochlorococcus (strain MED4) showed no significant differences in growth rate (Fu et al., 2007) or expression of CCM genes with changes in CO2 concentration (Hopkinson et al., 2014; Bagby and Chisholm, 2015). Yet, significant expression changes of high light inducible (hli) genes resulted from shifts in O2:CO2 ratio (Bagby and Chisholm, 2015), leaving open the question of whether Prochlorococcus can sense and acclimate to changes in CO2.

The Prochlorococcus high light II ecotype, exemplified by the strain MIT9312 and used as the model cyanobacterium in this work, is dominant in surface waters of the tropics and subtropics (Johnson et al., 2006). Like all Prochlorococcus strains sequenced to date, MIT9312 lacks the catalase gene (Bernroitner et al., 2009). Catalase is a key enzyme for removing hydrogen peroxide, a dangerous byproduct of metabolism and a ubiquitous oxidant in the surface ocean environment (Cooper et al., 1988). Prochlorococcus strains are aided in detoxifying reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide by ‘helper’ bacteria including Alteromonas sp. (Morris et al., 2011, 2008). Alteromonas sp. are globally distributed heterotrophic bacteria (Ivars-Martínez et al., 2008), known to stably associate with Prochlorococcus in culture and to inhibit or promote growth of the cyanobacterium depending on strain and relative abundance (Morris et al., 2008; Avrani and Lindell, 2015; Aharonovich and Sher, 2016). Such studies have begun to investigate which factors drive these microbial interactions, yet there are many gaps in our understanding of these processes. Marine microbial interactions have the potential to greatly impact marine biogeochemical cycles and the structure of marine ecosystems including where and how quickly carbon is metabolized by the microbial loop (Azam and Malfatti, 2007). Given the biogeochemical importance of the relationship between Prochlorococcus and ‘helper’ bacteria like Alteromonas, it is vital to study the potential for changes in microbial interactions with rising CO2.

Materials and methods

Cultures

Six clones of high light II Prochlorococcus VOL4, a streptomycin-resistant derivative of strain MIT9312 (Morris et al., 2011), were isolated by dilution to extinction in Pro99 media. Prochlorococcus clones were pretreated with the helper bacterium Alteromonas sp. strain EZ55 as in Morris et al. (2011) that was originally isolated from another culture of high light II Prochlorococcus, strain MIT9215 (Morris et al, 2008). Before these experiments, six clonal isolates of EZ55 were obtained by streaking from a frozen glycerol stock onto yeast extract tryptone sea salts agar plates (per liter, 4 g tryptone, 2.5 g yeast extract, 15 g sea salts (Sigma-Aldrich, Carlsbad, CA, USA, product no. S9883), and 15 g agar), picking isolated colonies into fresh yeast extract tryptone sea salts medium and were cryopreserved in 20% glycerol at –80 °C. Prochlorococcus clones were made axenic by addition of streptomycin (Morris et al., 2008) and cryopreserved by adding dimethylsulfoxide to a final concentration of 7.5% and flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen (Moore et al., 2007). For co-culture experiments, each of the six replicate Prochlorococcus cultures were initiated from a single Prochlorococcus cell and a different EZ55 clonal population.

Media and culture conditions

All cultures were grown in PEv medium (artificial seawater amended with Pro99 nutrients at 1/25 standard concentrations). The artificial seawater medium (28.41 g NaCl, 7.21 g MgSO4*7 H2O, 5.18 g MgCl2*6 H2O, 1.58 g CaCl2*2 H2O, 0.789 g KCl per liter) was autoclaved, amended with sterile-filtered Pro99 nutrients (Andersen, 2005) and 2.325 mM (final concentration) sodium bicarbonate, then aseptically bubbled overnight with ambient air. Cultures were grown in 13 ml acid-washed conical bottom glass centrifuge tubes with screw caps. Cultures were prepared by placing 12.3 ml of fresh medium into a sterile tube, followed by amendments totaling 0.2 ml (either sterile milli-Q water for ambient CO2 cultures, or a combination of sterile NaHCO3, HCl, and milli-Q water for elevated CO2 cultures) and 0.5 ml of a previous culture, leaving almost no headspace in the sealed tube. Inoculated tubes were placed on a tissue culture rotator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in a Percival growth chamber at 21 °C under 150 μmol photons m−2 s−1 on a 14:10 light–dark cycle. Preliminary tests with sterile media confirmed that the tubes were airtight and that elevated CO2 conditions were stable in sterile media over at least a 1-week period.

Carbonate chemistry

Parameters of the carbonate system in culture media were determined by separately measuring pH and alkalinity and using these values to calculate dissolved inorganic carbon and CO2 using the seacarb package in R (Gattuso and Lavigne, 2009). Alkalinity was assessed by titration with certified 0.1N HCl (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a Mettler-Toledo automatic titrator (Dickson et al., 2007). Medium pH was determined potentiometrically with a Mettler-Toledo electrode calibrated against standardized solutions of Tris-buffered seawater (Dickson et al., 2007). After determination of the baseline carbonate chemistry of a batch of medium, the ‘oa’ function in seacarb was used to determine additions of calibrated sodium bicarbonate and hydrochloric acid stocks needed to adjust pCO2 to approximately 800 p.p.m. Stability of media carbonate chemistry was assessed for test cultures with similar maximum biomass to experimental cultures (Supplementary Table 1). The pCO2 slightly increased over the growth period in all cultures indicating a shift toward net heterotrophy, likely supported by trace organic carbon in the media salts. Regardless, the treatments remained stably distinct between ambient and elevated CO2 (Supplementary Table 1).

Growth experiments

Each of the six Prochlorococcus clones was grown in ambient or elevated CO2 in co-culture with one of six Alteromonas clones in PEv media as described above. Prochlorococcus cell density was measured approximately every 2 days with a Guava Flow Cytometer (EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Alteromonas cell density was determined by plating serial dilutions of cultures on yeast extract tryptone sea salts agar. Care was taken to minimize perturbations of the carbonate chemistry during subsampling by minimizing headspace and the time tubes were open. Briefly, a 10 μl subsample was quickly removed from each tube and diluted in 90 μl of artificial seawater. When cell densities exceeded 1.3 × 106 cells ml−1, cultures were diluted 26-fold into fresh culture media. Cultures were allowed to acclimate to their target CO2 conditions through one transfer (approximately five generations), and then growth rate was measured over at least two further transfers. To determine the impact of Alteromonas on Prochlorococcus growth, streptomycin was added to co-cultures to a final concentration of 100 μg ml−1, rendering the streptomycin-resistant Prochlorococcus sp. strain VOL4 axenic by killing the streptomycin-sensitive Alteromonas cells. Axenic Prochlorococcus was transferred twice under ambient or elevated CO2 or until cell densities failed to reach 106 cells ml−1 within 1 month. Axenic status of cultures was confirmed each time the culture was sampled for cell density, by spotting 10 μl of culture onto a yeast extract tryptone sea salts agar plate.

Four growth parameters were measured by manual inspection of at least two consecutive growth curves for each biological replicate. Realized growth rates m were calculated as the exponential change over time t in population density from the inoculation of the first culture (NI) through the end of the final culture (NE) after three or more (x) 26-fold transfers using the formula

Exponential growth rates μ were calculated as the slope of the regression of log cell density versus time for several measurements taken during the exponential growth phase of each individual culture; r2 values for these estimates were generally >0.99. Lag phase duration (L) was calculated as the difference between the actual duration of each individual culture (d) and the time expected if the culture had been growing exponentially at rate (r) starting with its initial inoculation at cell density (N0) until its final density (Nt):

Finally, we observed that in most cases longer lag phases occurred along with a substantial decrease in cell densities after culture inoculation, suggesting a die-off of cells after exposure to fresh media. We calculated the magnitude of this die-off (D) by first calculating the ratio of the lowest cell density measurement (Nmin) over the initial cell density measurement, and subtracting this value from 1 to yield a proportion:

The significance of differences in culture parameters was determined using linear mixed effects models with CO2 concentration and presence/absence of Alteromonas as fixed effects and Prochlorococcus strain as a random effect. P-values were determined by comparing full models containing both fixed effects with null models omitting one or both. Models were fit in R v 3.3.1 using the lme4 package (https://www.r-project.org/). Pairwise comparisons were performed using R packages multcomp and lsmeans.

RNA library prep and sequencing

Cultures for RNA preparations were prepared as for the growth experiments. Briefly, co-cultures of Prochlorococcus and Alteromonas or axenic Alteromonas cultures were transferred twice under ambient or elevated CO2 in the same media and culture conditions described above and totaling approximately 10 generations before being harvested for RNA. After this acclimation step, co-cultures were split from a single tube to five technical replicate tubes, whereas axenic Alteromonas cultures were grown in 1 liter polycarbonate bottles with minimal headspace to increase biomass yield. To further reduce carbon chemistry perturbations for RNA experiments, growth was measured without opening the co-culture tubes by using a Trilogy fluorometer (Turner Designs, San Jose, CA, USA) fitted with a custom three-dimensional-printed cuvette designed to accept conical bottom centrifuge tubes. Co-culture fluorescence was measured daily, when at least three of these replicates crossed the cutoff value of about 5 × 106 cells ml−1, all replicates were pooled to yield approximately 3 × 108 Prochlorococcus cells in 65 ml and harvested by gentle filtration (⩽30 kPa) on a 25 mm 0.2 μm polycarbonate filter. At the time of harvest for axenic Alteromonas cultures, carbonate chemistry was confirmed with pH measurements (Supplementary Table 1) and cell concentrations were determined with spot-titer plating, yielding approximately 3 × 108 Alteromonas cells in 200 ml, harvested by gentle filtration (⩽30 kPa) on a 25 mm 0.2 μm polycarbonate filter. Filters were flash frozen and stored at –80 °C until RNA extraction.

RNA extractions were performed with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) with a small modification to the lysis procedure. Lysis was performed by adding 0.6 ml Buffer RLT and ~250 μl zirconium/silica beads (0.5 mm) and vortexing for 5 min at 250 r.p.m. Genomic DNA was removed by an on-column DNase digestion with RNase-free DNase I (Qiagen). Ribosomal RNA was removed with the Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit (Bacteria) (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). After rRNA depletion, samples were purified and concentrated using the RNeasy MinElute cleanup kit (Qiagen). Post-digested RNA was assessed for quantity and quality with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The mRNA libraries were prepared for Illumina Hi-seq 2500 paired-end sequencing (PE100) with TruSeq RNA sample Prep Kit v2 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Fragmentation size target was 100 bp, paired-ends were non-overlapping with an insert size of approximately 300 bp. Samples were barcoded for multiplex sequencing and run in a single lane by the Sulzberger Columbia University Genome Center (CUGC) (New York, NY, USA). Sequence files are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) through BioProject (accession: PRJNA377729) and Sequence Read Archive (SRA) accession numbers SRR5320558-SRR5320569 and SAMN07374746 – SAMN07374757.

Sequence read processing and alignment

Sequence reads were processed at the sequencing facility using the default setting from bcl2fastq, coupled with adaptor trimming to remove barcodes. The subsequent fastq data release were additionally assess with FastQC (www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/). All sequencing reads passed this quality control and required no further trimming. Reads were aligned to both the MIT9312 gene models (accession: NC_007577.1) and the draft EZ55 genome (Genbank accession SRX022631) using bowtie2 with sensitive end-to-end mode (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). Reads aligning to coding sequences in the MIT9312 gene models were counted with samtools idxstats (Li et al., 2009). Reads aligning to the coding regions of EZ55 draft genome were counted with HT-seq count (Anders et al., 2015) because of the ability of HT-seq to count by region without requiring alignment to gene models, which were not available for the draft genome.

Differential gene expression and gene set enrichment analyses

Read counts were normalized using trimmed mean of M-values (Robinson and Oshlack, 2010) to estimate transcript abundances corrected for any differences in sequencing library preparation. Differential expression probabilities and fold change of gene expression in elevated CO2 compared with ambient were calculated from normalized transcript abundances with edgeR (McCarthy et al., 2012) using a general linear model to estimate the tag-wise common dispersion with a paired-sample design to minimize the impact of strain–strain variability. Genes with significant differential expression (P<0.05, exact test, edgeR) were tested for gene set enrichment as follows: gene set categories were chosen from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways except those noted as keyword searches from annotations, then gene set enrichment probabilities were calculated with a hypergeometric test (phyper, stats, R) for genes with increased (log2 fold change>0) and decreased (log2 fold change<0) expression that fell into pre-defined categories compared with the total number genes in the same category within the genome.

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM)

Co-cultures of Prochlorococcus (VOL4, MIT9312) and Alteromonas (EZ55) were acclimated to target CO2 conditions as described above before being used to inoculate approximately 1.2 liter of PEv medium in clear polycarbonate bottles. These bottles were filled, leaving very little headspace and sealed with parafilm before incubation. When cultures exceeded approximately 106 cells ml−1 they were collected by gentle filtration on a 47 mm, 0.2 μm polyethersulfone membrane filter and resuspended in 1 ml of a sterile mixture of artificial seawater and milli-Q water (1:1). The resuspended cells were concentrated 50-fold by centrifugation (10 min, ~18 000xg). The resulting preparation contained between 1010 and 1012 cells ml−1, and was kept in a cool dark box during transport to the cryo-EM facility where cells were immediately cryogenically frozen in preparation for microscopy.

For cryo-EM, 3 μl of the Prochlorococcus suspension were applied to glow-discharged 200 mesh Quantifoil R 2/1 Nickel grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) and vitrified in liquid ethane using an FEI Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The grids were observed on an FEI Tecnai F20 electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operated at 200 kV with typical magnification × 38 000 and 4–10 μm defocus. Images were collected under low-dose conditions using a Gatan Ultrascan 4000 CCD camera. Only images where internal cell structures were sufficiently visible were included in further analysis. Carboxysomes were visible as dark inclusions within cells, generally with a visible hexagonal shape, and were counted manually for each image. Statistical tests were performed in R using the wilcox.test function (package stats).

Hydrogen peroxide degradation rates

Concentrations of H2O2 were determined using the protocol of Morris et al. (2011) modified for use in a Synergy H1 plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). In brief, 2 ml samples were removed from cultures and sterile H2O2 was added to approximately 250 nm starting concentration. Duplicate 200 μl samples were then removed into black 96-well plates every 15 min for 1 h for H2O2 determination by sequential injections of 50 μl 2 m Na2CO3 (pH 11.3), and 3.5 mM acridinium NHS ester (pH 3, Cayman Chemical) followed by integration of chemiluminescent light emission for 1 s. Absolute determination of H2O2 concentration was achieved by comparison against a standard curve produced by adding H2O2 from 0 to 500 nM to artificial seawater media. Before calculations, chemiluminescent output of all samples was adjusted by subtracting the readings for a true blank to which 10 μM sodium pyruvate had been added to eliminate any incidental H2O2. Degradation rate constants were calculated as the regression of log H2O2 concentration versus time and normalized to Alteromonas cell concentration determined from spot-titer plating.

Results and discussion

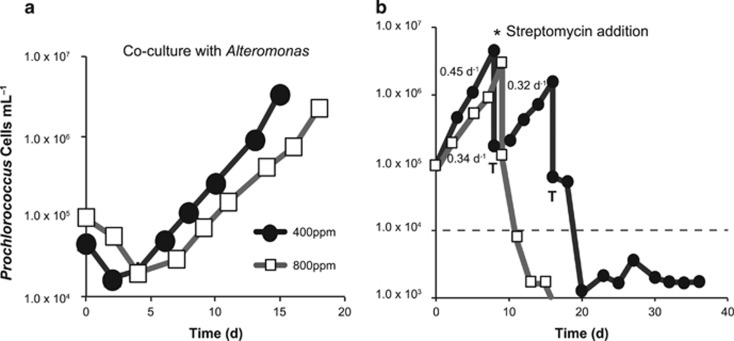

The impact of rising CO2 on ocean ecosystems is a topic of increasing interest, however, little is known about the influence of rising CO2 on the microbial interactions that underpin these ecosystem dynamics. Here, a strain of the cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus (VOL4, MIT9312) was cultured with a heterotrophic bacterial isolate Alteromonas (EZ55) to investigate the potential for CO2-driven changes in Prochlorococcus physiology and the microbial interaction with Alteromonas (Figure 1). Six single-cell isolates of Prochlorococcus and Alteromonas were co-cultured under ambient (~400 p.p.m.) or elevated (~800 p.p.m.) CO2 (Supplementary Table 1) at low cell densities (< 5 × 106 cells ml−1 per culture) to prevent the alteration of carbonate chemistry, and to more closely mimic in situ cell densities.

Figure 1.

Representative growth curves of Prochlorococcus under ambient and elevated CO2. (a) Cell density (cells ml−1) versus time (days) of Prochlorococcus (VOL4, MIT9312) in co-culture with Alteromonas (EZ55) at 400 p.p.m. (black circles) or 800 p.p.m. (white squares) CO2. Growth statistics are in Table 1. (b) Cell density of Prochlorococcus (VOL4, MIT9312) over consecutive transfers (indicated by ‘T’) in co-culture with Alteromonas (EZ55). The asterisk indicates addition of streptomycin rendering Prochlorococcus axenic, the dashed line indicates the limit of detection and the numbers are exponential growth rate constants (day−1) calculated from growth curves.

Prochlorococcus in co-culture with Alteromonas had a realized growth rate (m) 47% slower under elevated CO2 compared with ambient CO2 (Figure 1a,Table 1). There was no significant difference between CO2 treatments in the true exponential growth rates (μ), similar to the findings of Fu et al. (2007). Instead, the observed difference in realized growth rate was due to a significantly longer lag phase duration (P =1.48 x 10−5, linear mixed effects model) (Table 1). Longer lag durations (L) were often coupled with substantial die-offs (D) during the days after inoculation. The magnitude of these die-offs was significantly greater under elevated CO2 than ambient conditions (P=8.46 × 10−5) (Table 1). Previous experiments have shown that die-offs in Prochlorococcus cultures are often attributable to increased oxidative stress, which can be mitigated by the presence of helper heterotrophic bacteria such as Alteromonas (Morris et al., 2011; Coe et al., 2016). These observations suggest that Prochlorococcus may experience greater oxidative stress under elevated CO2 even in the presence of the ‘helper’ bacterium Alteromonas, and highlights the importance of accounting for microbial interactions in evaluating changes in growth rate and mortality under future CO2 scenarios.

Table 1. Growth parameters of Prochlorococcus with or without Alteromonas under ambient (~400 p.p.m.) or elevated (~800 p.p.m.) CO2 regimes.

| CO2 treatment | m (day−1) | μ (day−1) | L (day) | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambient | 0.353±0.040 | 0.440±0.023 | 2.21±1.38 | 0.223±0.165 |

| Elevated | 0.187±0.041 | 0.426±0.071 | 10.14±3.53 | 0.688±0.164 |

| Ambient axenic | 0.048±0.060 | 0.219±0.098 | 9.73±10.82 | 0.539±0.286 |

| Elevated axenic | 0.027±0.086 | 0.095±0.124 | 4.57±10.93 | 0.699±0.443 |

Values are means of replicate cultures±95% confidence intervals (n=6, non-axenic; n= 7, ambient axenic; n=4, elevated axenic). m, realized growth rate over at least two consecutive batch cultures; μ, exponential growth rate of individual cultures; L, lag phase duration; D, die-off proportion.

To test the importance of Alteromonas in mitigating the negative impacts of high CO2, we attempted to render co-cultures axenic with the addition of the antibiotic streptomycin. Under ambient CO2, all six Prochlorococcus cultures that were successfully rendered axenic were able to survive at least one growth cycle (Figure 1b), but survivorship was much lower under elevated CO2, with only a quarter of successfully purified cultures surviving two growth cycles. Where axenic cultures survived, they had significantly reduced growth rates (P<0.001) compared with co-cultured Prochlorococcus in both ambient and elevated CO2 (Table 1). This supports the findings of previous studies on the toll of oxidative stress on axenic Prochlorococcus in the absence of a ‘helper’ heterotroph (Morris et al., 2011), and suggests that the impact of natural oxidative stress is at least partially mitigated by the presence of Alteromonas under both CO2 treatments. Interestingly, Alteromonas seemed more resistant to streptomycin at high CO2: only 4 of 12 attempts were successful in creating an axenic culture compared with 7 of 9 under ambient CO2. We hypothesize that a change in Alteromonas metabolism may have reduced sensitivity to streptomycin at elevated CO2, either as a result of changing microbial interactions or in response to acidification. Of the four axenic Prochlorococcus cultures at elevated CO2, only two cultures survived the first growth cycle and none survived beyond the second, so differences in growth parameters could not be statistically tested (Table 1), nor could changes in gene transcription be evaluated for axenic Prochlorococcus.

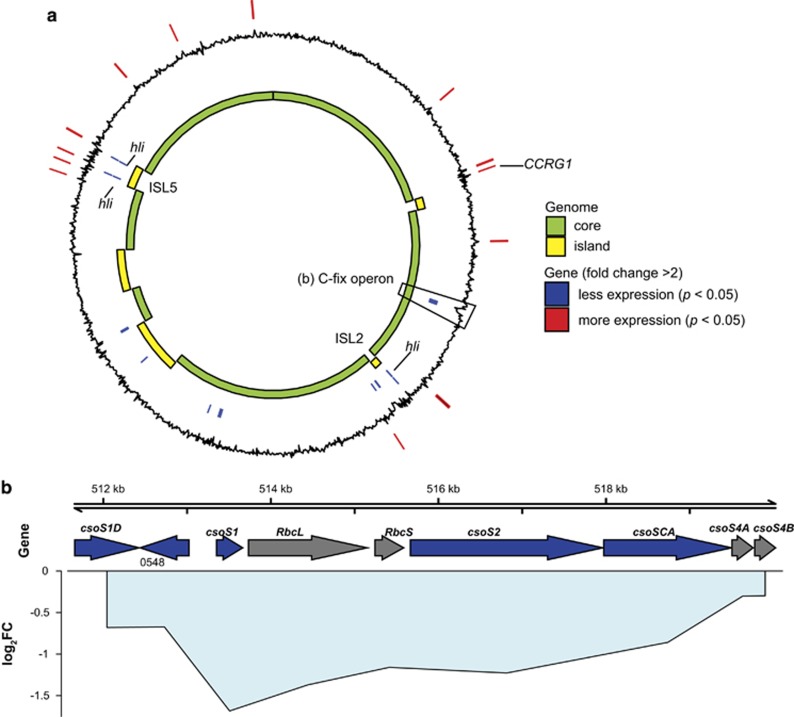

To investigate how elevated CO2 impacts the metabolic functions of Prochlorococcus and interactions with ‘helper’ bacterium Alteromonas, whole transcriptomes of the co-cultures under ambient and elevated CO2 were sequenced. Among transcripts aligning to the Prochlorococcus (MIT9312) genome, only 35 genes were differentially expressed (P<0.05, fold change >2) under elevated CO2 (Figure 2,Supplementary Table 2). There were significant decreases in expression of high light inducible (hli) genes from genomic islands in response to elevated CO2 (Figure 2a). Decreased expression of hli genes from the genomic islands (non-core genome) was previously observed for increasing CO2:O2 ratio in the high light I MED4 strain of Prochlorococcus (Bagby and Chisholm, 2015). The functions of these genes are not known, but are potentially involved in photorespiration or the oxidative stress response. Notably, there was an approximately twofold decrease in transcripts of an apparent carbon fixation operon (Figure 2b). Not all genes in the carbon fixation operon met our threshold for significant differential expression, including the Rubisco subunits; however, decreased expression of the carboxysome subunits csoS1D, csoS1, and csoS2 and csoSCA were statistically significant (P<0.05) (Figure 2b). Decreased expression of carboxysome subunits of a similar magnitude was observed under elevated CO2 experiments with MED4, but the changes were not statistically significant because of large uncertainties (Hopkinson et al., 2014).

Figure 2.

Prochlorococcus differential gene expression under elevated CO2. (a) Whole-genome view of differentially expressed genes (n=35) in relation to core and flexible genome (that is, islands) for Prochlorococcus. Black line indicates log2 fold change in expression, with positive (outward) indicating genes with increased expression, and negative (inward) values indicating decreased expression under elevated CO2. Positions of significantly differentially expressed genes (pairwise exact test, P<0.05, n=6, with fold change >2) are indicated by lines on the outer ring (red) for genes with increased expression, and the inner ring (blue) for genes with decreased expression. (b) Region containing the putative operon with genes for carbon fixation (C-fix operon): Rubisco (RbcL, RbcS), carboxysome subunit genes (csoS1D, csoS1, csoS2, csoSCA, csoS4A and csoS4B). Arrows indicate location and strand of genes, primary colors indicate significant differential expression (P<0.05, n=6, blue=decreased, gray= no significant difference) under elevated CO2, lines indicate the mean log2 fold change (log2FC) of each gene, centered on each gene’s position in the genome, and are filled with light blue (decreased expression) to indicate cohesiveness of fold change across multiple genes.

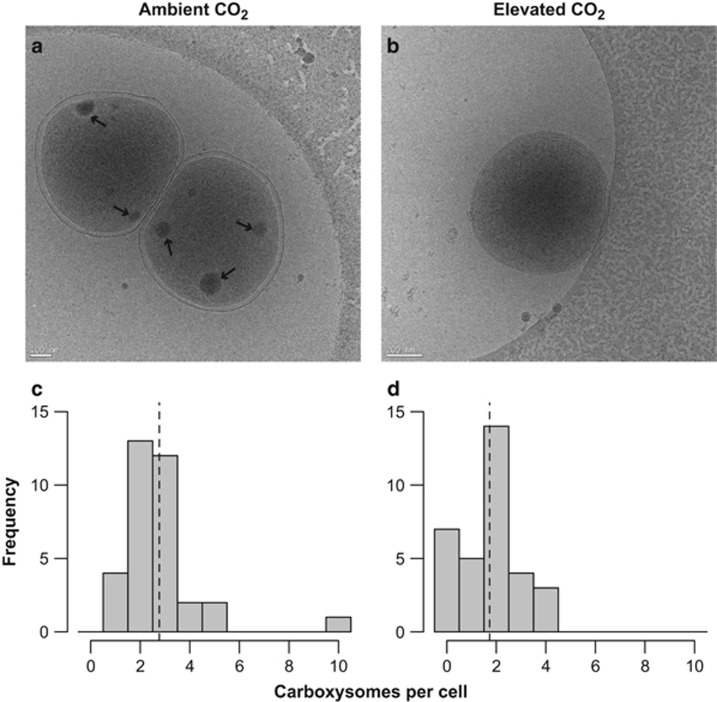

One of the significantly differentially expressed carboxysome subunit genes, csoSCA, also functions as a carbonic anhydrase (So et al., 2004; Ting et al., 2015). The observed decreased expression of csoSCA supports the hypothesis that under elevated CO2, phytoplankton downregulates CCM genes because of increased diffusive supply of CO2, or pH-induced transcriptional regulation. There was no significant change in expression of the bicarbonate transporter genes (Supplementary Table 2) in agreement with a previous study on MED4 (Hopkinson et al., 2014). Our data suggest that carboxysome and bicarbonate transporter genes are regulated by separate mechanisms, a conclusion supported by the existence of different conserved sequence motifs for carboxysome subunits and bicarbonate transporters in Prochlorococcus strains (Ting et al., 2015). The lack of a significant shift in expression of energy-consuming bicarbonate transporter genes may indicate that there would not be a significant energetic savings for Prochlorococcus under elevated CO2. However, a shift in the expression of carboxysome subunit genes would be expected to have a significant impact on the morphology or number of carboxysomes per cell. To investigate this possibility, cell cultures were imaged with cryo-EM to determine whether the transcriptome changes resulted in a change in cell morphology. Under ambient CO2, there were typically two to three carboxysome structures per Prochlorococcus cell (Figures 3a and c), with as many as ten observed in one cell. Exposed to elevated CO2, Prochlorococcus cells frequently contained no apparent carboxysomes (Figure 3b), with typical cells containing two carboxysomes and rarely more (Figure 3d). The number of carboxysomes per cell was significantly greater in ambient (mean 2.76) compared with elevated CO2 (mean 1.73) treatments (P<0.01, Mann–Whitney U-test). There were a higher proportion of large diameter (>125 nm) carboxysomes in Prochlorococcus cells exposed to elevated CO2 (Supplementary Figure 1); however, the differences in diameter (mean ~80 nm) were not statistically significant and were similar to the range (~90–130 nm) previously observed for Prochlorococcus (Ting et al., 2007).

Figure 3.

Carboxysome content per Prochlorococcus cell with example cryo-electron micrographs. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) images of Prochlorococcus cells acclimated to (a) ambient (~400 p.p.m.) CO2 and (b) elevated (~800 p.p.m.) CO2 (b). Arrows indicate location of carboxysome structures. Histograms of carboxysome structures per cell acclimated to (c) ambient or (d) elevated CO2 (n=34 and 33 cells, respectively). Dashed lines represent the mean number of carboxysomes per cell in each treatment.

The finding that Prochlorococcus had a 37% decrease in carboxysomes per cell at elevated compared with ambient CO2 agrees remarkably well with the ~50% decrease in expression of carboxysome genes. Despite this measurable difference in cell structures associated with carbon concentration and fixation, exponential growth rates did not change significantly (Table 1). We infer that Rubisco in carboxysome structures was not the limiting step for carbon fixation under these conditions, similar to the findings of Hopkinson et al. (2014) for MED4. However, assuming that the efficiency of carbon fixation via carboxysomes remains the same, fewer carboxysomes per cell indicates that the maximum capacity for carbon fixation via carboxysomes declined in response to elevated CO2.

In addition to changes in cell morphology, the Prochlorococcus transcriptome data revealed a possible shift in the interspecies interaction with Alteromonas. A Prochlorococcus gene of unknown function, termed co-culture responsive gene 1 (CCRG1) by Aharonovich and Sher (2016), had the highest fold increase under elevated CO2 (Supplementary Table 2). This gene was previously characterized by its significantly increased expression in a low light IV Prochlorococcus strain co-cultured with a different strain of Alteromonas. Although CCRG1 is not completely conserved, it is found in strains belonging to both high light and low light Prochlorococcus ecotypes (Aharonovich and Sher, 2016). The increased expression of CCRG1 under elevated CO2 is unanticipated because the concentration of Alteromonas remained relatively constant across all measured time points at 5.34±1.2 × 106 cells ml−1 at ambient CO2 and 4.48±1.27 × 106 cells ml−1 at elevated CO2 (mean±95% confidence interval), and these values were not significantly different between CO2 treatments (t-test, df=122, P=0.34). In low light IV Prochlorococcus (strain MIT9313), CCRG1 expression was associated with production of a largely intracellular protein whose function remains unknown, despite phylogeny suggesting it originated before the diversification of the Prochlorococcus lineage (Aharonovich and Sher, 2016).

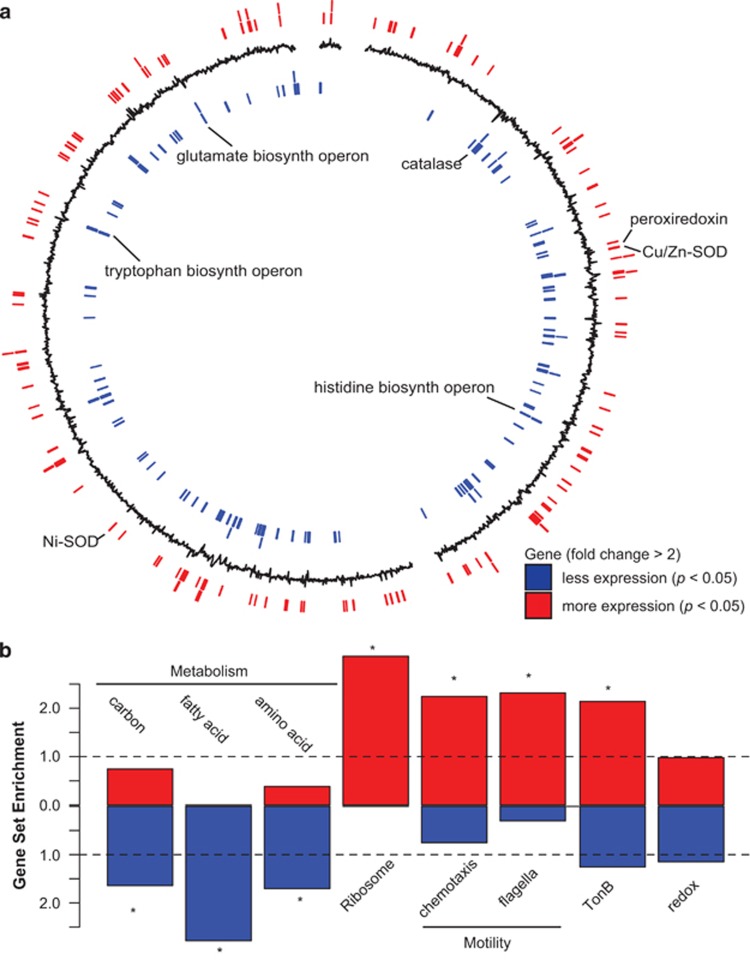

In light of these changes in Prochlorococcus gene expression, transcriptome sequences of the ‘helper’ bacterium Alteromonas, with and without Prochlorococcus under elevated and ambient CO2, were used to interrogate the potential shift in the nature of the interspecies interaction. Indeed, there were over 400 genes with significant differential expression between CO2 treatments (P<0.05, fold change >2) (Figure 4, Supplementary Table 3) in Alteromonas co-cultured with Prochlorococcus. Even after correcting for its larger gene complement, Alteromonas had a greater gene expression response than Prochlorococcus (8.5% of Alteromonas versus 1.8% of Prochlorococcus genes were significantly differentially expressed). Alteromonas cultures without Prochlorococcus had a smaller gene expression response to elevated CO2 relative to co-cultures with 128 genes (P<0.05, fold change >2) (Supplementary Table 4). These results suggest a more complex change in the interaction with Prochlorococcus under elevated CO2 rather than a direct response of Alteromonas to elevated CO2.

Figure 4.

Alteromonas differential gene expression under elevated CO2. (a) Whole-genome view of differentially expressed genes for Alteromonas (strain EZ55). Black line indicates log2 fold change in expression, with positive (outward) indicating genes with increased expression, and negative (inward) values indicating decreased expression under elevated CO2. Positions of significantly differentially expressed genes (pairwise exact test, P<0.05, n=6, with fold change >2) are indicated by lines on the outer ring (red) for genes with increased expression, and the inner ring (blue) for genes with decreased expression. Select genes and putative operons are labeled. (b) Gene set enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (P<0.05, n=6), with increased expression (red) or decreased expression (blue) for KEGG categories of carbon, amino-acid and fatty acid metabolism, ribosome, chemosynthesis, and flagellar genes, as well as categories defined by annotation keyword: TonB and redox (Supplementary Table 5). Dashed line indicates expected ratio of genes in a set based on the number of genes within the same set in the genome, asterisk indicates the gene set is significantly enriched (hypergeometric test, P<0.05) compared with the expected value of random selection from the genome.

Gene set enrichment analysis was performed to determine which categories of genes were significantly skewed toward lower or higher expression in Alteromonas in co-culture with Prochlorococcus under elevated CO2 (Figure 4b, Supplementary Table 5). Gene sets with lower expression under elevated CO2 included carbon, fatty acid and amino-acid metabolism (Figure 4b). However, only certain amino-acid metabolic pathways in Alteromonas had lower expression, including putative tryptophan, histidine and glutamate biosynthesis operons (Figure 4a). Ribosomal genes, chemotaxis-related genes and TonB-dependent transporters were over-represented in genes with significantly increased transcript abundance under elevated CO2 (Figure 4b,Supplementary Table 5). Similar expression changes in flagellar and chemotaxis genes have been observed in response to low pH in Escherichia coli (Maurer et al., 2005), potentially as a pH homeostasis strategy, however, a similar expression pattern was not observed in axenic Alteromonas exposed to elevated CO2 (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). None of the previously characterized pH homeostasis genes identified in a mesocosm experiment from marine heterotrophic bacteria (Bunse et al., 2016) had significantly increased expression in Alteromonas under elevated CO2. However, several dehydrogenase genes, which encode enzymes that produce hydrogen ions, had significantly decreased expression in both co-cultured and axenic Alteromonas under elevated CO2 (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4), suggesting another potential strategy to decrease hydrogen ion concentrations within the cell.

In order to elucidate how ecosystem services provided by Alteromonas might change in the future ocean, we examined the response of genes that alter concentrations of ROS. Redox-related genes were found to have both higher and lower relative transcript abundance in co-cultured Alteromonas under elevated CO2 with no significant enrichment compared with the genome (Figure 4b). The gene primarily responsible for catalyzing the removal of hydrogen peroxide, catalase, had significantly lower expression in Alteromonas in co-culture with Prochlorococcus under elevated CO2 (Figure 4a,Supplementary Table 3), but not in Alteromonas alone. In both co-cultured and axenic Alteromonas, there was a significant decrease in the expression of the Ohr family peroxiredoxin (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4), which is thought to degrade organic peroxides. In addition, two superoxide dismutase genes (Cu/Zn SOD and Ni SOD) responsible for the conversion of superoxide to hydrogen peroxide (Figure 4a, Supplementary Table 3) had significantly increased expression in Alteromonas in co-culture with Prochlorococcus. This suggests that Alteromonas may be producing hydrogen peroxide at a greater rate and/or degrading it more slowly, thereby increasing oxidative stress in Prochlorococcus under elevated CO2 compared with ambient CO2. Previous evidence points to removal of ROS as a cornerstone of the microbial interaction between Prochlorococcus and marine bacteria such as Alteromonas (Morris et al., 2011), so shifts in expression of these genes is evidence of a potential shift in the microbial relationship of these ecologically important marine bacteria. To test whether these gene expression changes resulted in changes in Alteromonas’ ability to protect Prochlorococcus from oxidative stress, the degradation rates of hydrogen peroxide were measured under ambient and elevated CO2 for co-cultures of Prochlorococcus and Alteromonas as well as axenic Alteromonas (Table 2). There was more than a sixfold decrease in the degradation rate of hydrogen peroxide at elevated CO2 in co-cultures of Prochlorococcus and Alteromonas (Table 2). The average degradation was also lower in axenic Alteromonas cultures under elevated CO2, but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2). These results strengthen the hypothesis that the catalase gene has a key role in eliminating ROS such as hydrogen peroxide. The change in hydrogen peroxide degradation also helps explain the higher mortality rate observed for Prochlorococcus under elevated CO2 (Table 1), apparently because of a decline in the expression of catalase in the ‘helper’ bacterium Alteromonas in co-culture with Prochlorococcus.

Table 2. Hydrogen peroxide degradation rates of Prochlorococcus in co-culture with ‘helper’ bacterium Alteromonas and axenic Alteromonas.

| Culture | Ambient CO2 (modern) | Elevated CO2 (year 2100) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-cultures | 2.57±1.86 | 0.42±0.23 | 0.03 |

| Axenic Alteromonas | 1.09±1.00 | 0.77±0.30 | NS |

Normalized degradation rates of hydrogen peroxide (10−9 min−1 Alteromonas cell−1) mean±s.d. (n=4 for co-culture and n=6 for axenic Alteromonas) with P-value for differences between ambient and elevated CO2 (t-test, one-tailed), NS indicates not significant.

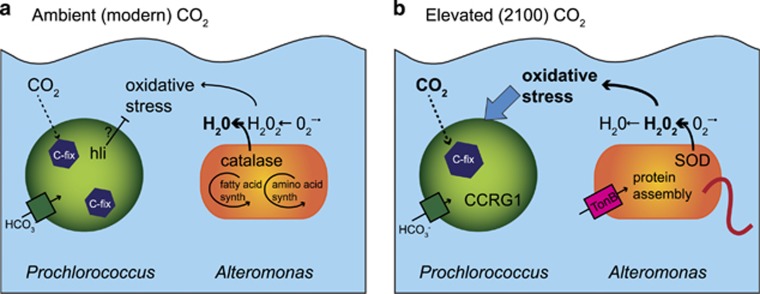

Putting these results together, we propose a new conceptual model for how primary production and microbial interactions may change with rising CO2 in the tropical and subtropical oceans where Prochlorococcus dominates (Figure 5). At ambient CO2, Prochlorococcus fixes inorganic carbon using a bicarbonate transporter and carboxysome structures to concentrate CO2 for the enzyme Rubisco (Figure 5a). In addition, hli genes expressed at higher levels under ambient CO2 may have a role in protecting Prochlorococcus from oxidative stress because of high light or unbalanced growth. Alteromonas uses the enzyme catalase to efficiently rid the cell and surrounding environment of hydrogen peroxide, benefiting the whole-microbial community, and allowing minimal genome organisms like Prochlorococcus to thrive (Morris et al., 2012). At elevated CO2 predicted for 2100, Prochlorococcus responds to a change in CO2 or pH by downregulating carboxysome genes, resulting in fewer carboxysome structures (Figure 5b). The cyanobacterium also experiences a higher level of oxidative stress, potentially because of decreased hli gene expression or from a shift in microbial interaction with Alteromonas. Prochlorococcus upregulates the CCRG1 gene potentially as a signaling or defense mechanism against bacterial attack. Concurrently, Alteromonas downregulates production of amino acids while upregulating TonB-dependent transporters, ribosomes for protein assembly, and chemotaxis and flagellar genes for motility (Figure 5b), perhaps in response to a higher abundance of dead and dying Prochlorococcus or the exchange of metabolites. In addition, Alteromonas downregulates the enzyme catalase and upregulates superoxide dismutase. The net result of these changes in enzyme levels is a decrease in the rate of hydrogen peroxide removal, exacerbating the oxidative stress of Prochlorococcus under elevated CO2. These changes in Prochlorococcus and Alteromonas gene expression and physiology suggest that key microbial interactions may shift in elevated CO2 from mutualism toward antagonism, potentially inhibiting the dominant primary producer in the tropical and subtropical oceans.

Figure 5.

Conceptual model of the interaction of Prochlorococcus and Alteromonas under ambient and elevated CO2. Prochlorococcus cell in green and Alteromonas cell in orange under (a) ambient, modern CO2 and (b) elevated CO2 predicted for 2100. Arrows indicate putative fluxes or transformations of metabolites, both passive (dashed), active (solid), and inhibitory (flat head arrow). Relative increases in fluxes or transformations indicated by bold arrows and text. The thick red line on Alteromonas represents flagellar and chemotaxis gene expression. high light induced (hli), CCRG1, superoxide dismutase (SOD), TonB-dependent transporters and related genes (tonB).

With the global importance of Prochlorococcus and its limited gene complement for acclimating to environmental change, it is vital to explore how microbial partnerships may shift to sustain or inhibit this dominant primary producer. Several lines of evidence point to fundamental changes in the microbial interaction between Prochlorococcus and Alteromonas under elevated CO2, which may underpin changes in Prochlorococcus ecophysiology. These changes include an apparent increase in dependence of Prochlorococcus on ‘help’ from other bacteria, increased expression of CCRG1 in Prochlorococcus and decreased expression of the catalase gene in Alteromonas with a concomitant decrease in hydrogen peroxide degradation. In a more complex natural ecosystem, another bacterium may provide the ecosystem services that decreased in Alteromonas. Our experiments were done in a simplified co-culture, whereas the web of microbial interactions in natural ecosystems are much more complex and merit further study in the light of these findings. Regardless, these changes in gene expression and physiology in both Prochlorococcus and the ‘helper’ bacterium Alteromonas underscore that the increase in CO2 expected for the end of this century can rapidly alter microbial partnerships at the base of the marine food web. Changes in interspecies interactions could in turn alter ecosystem dynamics and should be considered in future modeling efforts.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation Biological Oceanography Program #OCE13-14336 (STD) OCE 1233964 (ERZ) and #OCE 1540158 (JJM), with partial support also provided by WSL PURE in partnership with Columbia University's Center for Climate and Life. This work was also made possible by resources provided by the JP Sulzberger Columbia Genome Center and the Mason high performance computing cluster at the University of Indiana (NSF Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment project) with thanks to María Hernández Límon. We are grateful to Cynthia M Rodenburg for assistance with the electron microscopy that was carried out at the UAB cryo-EM facility, University of Alabama at Birmingham. Additional thanks to three anonymous reviewers for their comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aharonovich D, Sher D. (2016). Transcriptional response of Prochlorococcus to co-culture with a marine Alteromonas: differences between strains and the involvement of putative infochemicals. ISME J 10: 2892–2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. (2015). Genome analysis HTSeq — a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31: 166–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R (ed). (2005) Algal Culturing Techniques. Academic Press: Burlington, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Avrani S, Lindell D. (2015). Convergent evolution toward an improved growth rate and a reduced resistance range in Prochlorococcus strains resistant to phage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: E2191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam F, Malfatti F. (2007). Microbial structuring of marine ecosystems. Nat Rev Microbiol 5: 782–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby SC, Chisholm SW. (2015). Response of Prochlorococcus to varying CO2:O2 ratios. ISME J 9: 2232–2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernroitner M, Zamocky M, Furtmüller PG, Peschek GA, Obinger C. (2009). Occurrence, phylogeny, structure, and function of catalases and peroxidases in cyanobacteria. J Exp Bot 60: 423–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biller SJ, Berube PM, Lindell D, Chisholm SW. (2015). Prochlorococcus: the structure and function of collective diversity. Nat Publ Gr 13: 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buitenhuis ET, Li WKW, Vaulot D, Lomas MW, Landry MR, Partensky F et al. (2012). Picophytoplankton biomass distribution in the global ocean. Earth Syst Sci Data 4: 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bunse C, Lundin D, Karlsson CMG, Vila-Costa M, Palovaara J, Akram N et al. (2016). Response of marine bacterioplankton pH homeostasis gene expression to elevated CO2. Nat Clim Chang 6: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ciais P, Sabine C. (2013). IPCC Fifth Assessment Report Climate Change 2013: Chapter 6 Carbon and Other Biogeochemical Cycles. 1–167.

- Coe A, Ghizzoni J, LeGault K, Biller S, Roggensack SE, Chisholm SW. (2016). Survival of Prochlorococcus in extended darkness. Limnol Oceanogr 61: 1375–1388. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper WJ, Zika RG, Petasne RG, Plane JMC. (1988). Photochemical formation of hydrogen peroxide in natural waters exposed to sunlight. Environ Sci Technol 22: 1156–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson AG, Sabine CL, Christian JR. (2007). Guide to best practices for ocean CO2 measurements. PICES Spec Publ 3: 191. [Google Scholar]

- Dutkiewicz S, Morris JJ, Follows MJ, Scott J, Levitan O, Dyhrman ST et al. (2015). Impact of ocean acidification on the structure of future phytoplankton communities. Nat Clim Chang 5: 1002–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Fu FX, Warner ME, Zhang Y, Feng Y, Hutchins DA. (2007). Effects of increased temperature and CO2 on photosynthesis, growth, and elemental ratios in marine Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus (Cyanobacteria). J Phycol 43: 485–496. [Google Scholar]

- Gattuso J-P, Lavigne H. (2009). Technical note: approaches and software tools to investigate the impact of ocean acidification. Biogeosciences 6: 2121–2133. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson BM, Young JN, Tansik AL, Binder BJ. (2014). The minimal CO2-concentrating mechanism of Prochlorococcus spp. MED4 is effective and efficient. Plant Physiol 166: 2205–2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivars-Martínez E, D’Auria G, Rodríguez-Valera F, Sánchez-Porro C, Ventosa A, Joint I et al. (2008). Biogeography of the ubiquitous marine bacterium Alteromonas macleodii determined by multilocus sequence analysis. Mol Ecol 17: 4092–4106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ZI, Zinser ER, Coe A, McNulty NP, Woodward EMS, Chisholm SW. (2006). Niche partitioning among Prochlorococcus ecotypes along ocean-scale environmental gradients. Science 311: 1737–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9: 357–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N et al. (2009). The sequence alignment/ Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas MW, Hopkinson BM, Losh JL, Ryan DE, Shi DL, Xu Y et al. (2012). Effect of ocean acidification on cyanobacteria in the subtropical North Atlantic. Aquat Microb Ecol 66: 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer LM, Yohannes E, Bondurant SS, Radmacher M, Slonczewski JL. (2005). pH regulates genes for flagellar motility, catabolism, and oxidative stress in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 187: 304–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK. (2012). Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 4288–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LR, Coe A, Zinser ER, Saito Ma, Sullivan MB, Lindell D et al. (2007). Culturing the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus. Limnol Oceanogr Methods 5: 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Morris JJ, Johnson ZI, Szul MJ, Keller M, Zinser ER. (2011). Dependence of the cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus on hydrogen peroxide scavenging microbes for growth at the ocean’s surface. PLoS One 6: e16805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JJ, Kirkegaard R, Szul MJ, Johnson ZI, Zinser ER. (2008). Facilitation of robust growth of Prochlorococcus colonies and dilute liquid cultures by ‘helper’ heterotrophic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 4530–4534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JJ, Lenski RE, Zinser ER. (2012). The black queen hypothesis: evolution of dependencies through adaptive gene loss. MBio 3: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Oshlack A. (2010). A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol 11: R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So AK-C, Espie GS, Williams EB, Shively JM, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC. (2004). A novel evolutionary lineage of carbonic anhydrase (epsilon class) is a component of the carboxysome shell. J Bacteriol 186: 623–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting CS, Dusenbury KH, Pryzant RA, Higgins KW, Pang CJ, Black CE et al. (2015). The Prochlorococcus carbon dioxide-concentrating mechanism: evidence of carboxysome-associated heterogeneity. Photosynth Res 123: 45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting CS, Hsieh C, Sundararaman S, Mannella C, Marko M. (2007). Cryo-electron tomography reveals the comparative three-dimensional architecture of Prochlorococcus, a globally important marine Cyanobacterium. J Bacteriol 189: 4485–4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.