Abstract

The objective of the present study was to investigate the association between recurrent implantation failure (RIF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) gene polymorphisms that are associated with various female infertility disorders. A total of 116 women diagnosed with RIF and 218 control subjects were genotyped for the VEGF −2578C>A, −1154G>A, −634C>G and 936C>T polymorphisms using a polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism assay. The VEGF −2578AA genotype was associated with an increased prevalence (≥4) of RIF [adjusted odds ratio (AOR)=2.77; 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.10–7.02; P=0.031], whereas the VEGF −634CG+GG genotype was associated with an increased incidence of total RIF (AOR=2.03; 95% CI=1.02–4.05; P=0.044) and ≥4 RIF (AOR=3.16; 95% CI=1.19–8.37; P=0.021). The results of the haplotype analysis indicated that −2578A/-1154A/-634G/936C (AOR=1.76; 95% CI=1.03–3.00; P=0.040 for total RIF and AOR=2.11; 95% CI=1.12–3.97; P=0.021 for ≥4 RIF) was associated with the occurrence of RIF. In addition, it was revealed that there was a significant difference in serum prolactin level associated with the VEGF −634C>G polymorphism (P=0.013). Therefore the findings of the present study indicate that the VEGF −2578AA genotype, −634G allele and −2578A/-1154A/-634G/936C haplotype may be genetic markers for susceptibility to RIF. However, further studies on VEGF promoter polymorphisms that include an independent randomized-controlled population are required to confirm these results.

Keywords: vascular endothelial growth factor −2578C>A, vascular endothelial growth factor −1154G>A, vascular endothelial growth factor −634C>G, vascular endothelial growth factor 936C>T, polymorphism, prolactin, recurrent implantation failure

Introduction

Recurrent implantation failure (RIF) refers to when an implanted embryo repeatedly fails to result in the development of an intrauterine gestational sac following embryo transfer (ET), as determined by ultrasonography (1). RIF may simply be defined as two or more continuous implantation failures (2); however, researchers now prefer to define RIF as the failure to maintain a clinical pregnancy following three cycles of ET (3,4). Several causes of RIF have been reported, including embryo, uterine and immunological factors, as well as thrombophilic conditions, however, the genetic mechanisms underlying RIF remain unclear (1).

Embryo implantation is a multifactorial event that depends on the interaction of the blastocyst with the receptive endometrium and consists of molecular signaling by the embryo, followed by apposition and attachment to the endometrium (5). Following the formation of the fetal-maternal interface, the essential second step involves the invasion of the embryo endometrium (6). This invasion induces endometrial angiogenesis, which is promoted by numerous growth factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). VEGF increases vascular permeability and activates endothelial cell proliferation, migration, differentiation and capillary formation (6). The intrauterine concentrations of VEGF during the menstrual cycle were determined in women experiencing infertility and it was revealed that VEGF concentrations are cycle-dependent and increase during the late secretory and premenstrual phases (7). VEGF concentrations are also correlated with levels of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1, the decidualization marker of the endometrium (8). Sugino et al (9) examined the expression of VEGF and its receptors throughout the menstrual cycle and in early pregnancy. The results revealed that the expression of VEGF and its receptor were higher in the mid-secretory phase compared with the proliferative phase during normal menstrual cycles. There was also a marked expression of VEGF in decidual cells in early pregnancy. The authors concluded that VEGF contributes to the successful implantation and maintenance of pregnancy by increasing vascular permeability or by forming the vascular network in the decidua. Kapiteijn et al (10) cultured human embryos in VEGF-conditioned media as an in vitro model and demonstrated that VEGF induced endometrial angiogenesis in the embryos. The results of these previous studies indicate that VEGF may be a key regulator in angiogenesis and decidualization of the endometrium, which are essential processes for the maintenance of a successful pregnancy.

VEGF is located on chromosome 6p21.3 and is comprised of eight exons (11). Several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been previously detected in VEGF, including −2578C>A, −1154G>A, −634C>G and 936C>T, which are associated with altered VEGF expression (12–16). There have been several previous reports that VEGF polymorphisms are associated with the development and prognosis of a variety of obstetrical and gynecological diseases (17–19). Additionally, there have been reports that the VEGF −1154G>A and −634C>G polymorphisms are associated with the occurrence of RIF (20–23), however, only a small number of studies have evaluated the association between other functional VEGF polymorphisms and the incidence rate of RIF (24,25).

The objective of the present study was to examine whether single VEGF SNPs or the functional VEGF polymorphism haplotype −2578C>A (rs699947), −1154G>A (rs1570360), −634C>G (rs2010963) and 936C>T (rs3025039) may affect the susceptibility to RIF in Korean females.

Materials and methods

Study population

Blood samples were obtained from 116 females with RIF [median age (range), 34 years (27–45 years)] and 218 healthy female controls [median age (range); 33 years (24–66 years)]. All study participants were recruited from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of CHA Bundang Medical Center (Seongnam, South Korea) between March 2010 and December 2012.

In the present study, RIF was defined as the failure to achieve pregnancy following the completion of two fresh in vitro fertilization-ET cycles with >10 cleaved embryos and serum human chorionic gonadotrophin concentrations <5 U/ml 14 days after ET. All embryos were examined by an embryologist prior to transfer and judged to be of a good quality. The male and female partner in each couple experiencing RIF was evaluated. Subjects who were diagnosed with RIF due to anatomical, chromosomal, hormonal, infectious, autoimmune or thrombotic causes were excluded from the present study. Anatomical abnormalities were evaluated using several imaging modalities, including sonography, hysterosalpingogram, hysteroscopy, computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Karyotyping was conducted using standard protocols to assess chromosomal abnormalities (26,27). Hormonal causes of RIF, including hyperprolactinemia, luteal insufficiency and thyroid disease were excluded by measuring the concentrations of prolactin (PRL), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), estradiol (E2) and progesterone in samples of peripheral blood. Lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies were examined according to the protocols of a previous study (28) to exclude lupus and antiphospholipid syndrome as autoimmune causes of RIF. Thrombotic causes of RIF were defined as thrombophilia and were evaluated by the detection of protein C and S deficiencies and by the presence of anti-α2 glycoprotein antibodies using methods described in a previous study (29).

The enrollment criteria for the control group included regular menstrual cycles, normal karyotype (46, XX), a history of at least one naturally conceived pregnancy and no history of pregnancy loss, including abortion. Data collection methods for each group were identical.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of CHA Bundang Medical Center on 23 February 2010 (reference no. CHAMC2009-12-120). All study participants provided written informed consent prior to participating in the present study. All the methods applied in the study were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Hormone assays

Blood samples were collected by venipuncture on day 2 or 3 of the menstrual cycle for the measurement of FSH, LH, E2, TSH and PRL levels. Serum was prepared as previously described (30) and hormone levels were determined using either radioimmunoassays [E2 (cat. no., A21854), TSH (cat. no., IM3712) and PRL (cat. no., IM2121); Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA], or enzyme immunoassays using IMMULITE® 1000 Systems (FSH and LH; Siemens AG, Munich, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Genotype analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using the G-DEX IIc Genomic DNA Extraction kit (Intron Biotechnology Inc., Seongnam, Korea) and purified using the high-salt buffer method (31). DNA was diluted to 100 ng/µl with 1X TE (Tris-EDTA) buffer and subsequently 1 µl from each sample was used to amplify VEGF polymorphisms. Genotyping was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) restriction fragment length polymorphism using the following primers: VEGF −2578C>A polymorphism forward, 5′-GGATGGGGCTGACTAGGTAAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGCCCCCTTTTCCTCCAAC-3′ to generate a 308-bp (C allele) or 326-bp (A allele) product; VEGF −1154G>A polymorphism forward, 5′-CGCGTGTCTCTGGACAGAGTTTCC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CGGGGACAGGCGAGCTTCAG-3′ to generate a 173-bp (A allele) or 141-bp (G allele) product; VEGF −634C>G polymorphism forward, 5′-CAGGTCACTCACTTTGCCCCGGTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCTTGCCATTCCCCACTTGAATCG-3′ to generate a 204-bp (C allele) or 180-bp (G allele) product; VEGF 936C>T polymorphism forward, 5′-AAGGAAGAGGAGACTCTGCGCAGAGC-3′ and reverse, 5′-TAAATGTATGTATGTGGGTGGGTGTGTCTACAGG-3′ to generate a 208-bp (C allele) or 122-bp (T allele) fragment. The thermocycling conditions for each set of primers are presented in Table I and all PCR experiments were performed using an AccuPower® HotStart PCR PreMix (Bioneer Corporation, Daejeon, Korea). VEGF polymorphisms were identified by digesting the VEGF −2578C>A and −634G>C PCR products with the AvaII restriction endonuclease (New England BioLabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA) and the VEGF −1154G>A and 936C>T PCR products with MnlI and NlaIII restriction endonucleases (New England BioLabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA). All restriction digests were performed at 37°C for 16 h and detected using gel electrophoresis with 3% agarose gel and visualized with ethidium bromide on a Gel-Doc XR+ version system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Table I.

PCR conditions, primers and restrict enzyme used in the present study.

| Gene | rs# | PCR condition | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | R/E | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF −2578C>A | rs699947 | 94°C | 5 min | 35 cycles | F: GGATGGGGCTGACTAGGTAAG | AvaII |

| 94°C | 30 sec | R: AGCCCCCTTTTCCTCCAAC | ||||

| −62°C | 30 sec | |||||

| −72°C | 30 sec | |||||

| 72°C | 7 min | |||||

| VEGF −1154G>A | rs1570360 | 94°C | 5 min | 38 cycles | F: CGCGTGTCTCTGGACAGAGTTTCC | MnlI |

| 94°C | 30 sec | R: CGGGGACAGGCGAGCTTCAG | ||||

| −59°C | 40 sec | |||||

| −72°C | 30 sec | |||||

| 72°C | 5 min | |||||

| VEGF −634C>G | rs2010963 | 94°C | 5 min | 40 cycles | F: CAGGTCACTCACTTTGCCCCGGTC | AvaII |

| 94°C | 30 sec | R: GCTTGCCATTCCCCACTTGAATCG | ||||

| −63°C | 35 sec | |||||

| −72°C | 30 sec | |||||

| 72°C | 7 min | |||||

| VEGF 936C>T | rs3025039 | 94°C | 5 min | 35 cycles | F: AAGGAAGAGGAGACTCTGCGCAGAGC | NlaIII |

| 94°C | 30 sec | R: TAAATGTATGTATGTGGGTGGGTGTGTCTACAGG | ||||

| −68°C | 1 min | |||||

| −72°C | 30 sec | |||||

| 72°C | 7 min | |||||

PCR, polymerase chain reaction; rs#, RefSNP(rs) number; R/E, restriction enzyme; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; F, forward primer; R, reverse primer.

Statistical analysis

Differences in the genotype and haplotype frequencies between RIF subjects and controls were compared using multivariate logistic regression. Allelic frequencies were calculated to identify deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), using P<0.05 as the significance threshold as previously described (32,33). Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to measure the strength of the association between different genotypes and RIF. Association analysis was performed among groups that were stratified by implantation failure number. Patients with RIF were defined as those with ≥2 implantation failures and patients were divided into the following groups: Total RIF, ≥3 implantation failures (≥3 RIF) and ≥4 implantation failures (≥4 RIF). As there was no significant difference between the ≥3 RIF group and the total RIF group, the ≥4 RIF group was compared with the total RIF group. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Differences in hormone concentrations (E2, FSH, LH, PRL and TSH) in accordance with VEGF genotypes and alleles were evaluated using a one-way analysis of variance with a post-hoc Scheffé test for all pairwise comparisons and independent two-sample t-tests as appropriate. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA), StatsDirect version 2.4.4 (StatsDirect Ltd., Altrincham, UK) and PLINK version 1.07 (http://zzz.bwh.harvard.edu/plink/). Statistical power was calculated using the G*Power program version 3.1.7 (http://www.gpower.hhu.de/).

Transcription factor binding site prediction

The DNA sequence of the VEGF promoter was used to predict transcription factor binding sites. The P-Match (http://www.gene-regulation.com) (34,35) was used to predict the transcription factors that would bind to the region in VEGF promoter. P-Match is interconnected with the TRANSFAC® database (http://gene-regulation.com/).

Results

Baseline characteristics and the frequency of VEGF polymorphisms

The demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table II. Patient age and RIF was matched with the relevant control groups and the following characteristics were examined: Age, BMI, gestational age and hormone levels including estradiol, FSH, LH, TSH and PRL. The results demonstrated that there were no significant differences in RIF between patients with RIF and controls. The genotypic distribution and haplotype frequencies of VEGF −2578C>A, −1154G>A, −634C>G and 936C>T for all study participants are detailed in Table III. The HWE was observed for all VEGF polymorphic sites analyzed in each group. The frequencies of the VEGF −2578CC, −1154GG, −634CC and 936CC genotypes corresponding to the reference genotypes of the four polymorphisms were 51.4, 72.0, 18.8 and 69.3% in the control group and 48.3, 67.2, 10.3 and 67.2% in the RIF group. Furthermore, the frequency of the VEGF −2578C/-1154G/-634C/936C haplotype was 42.0% in the control group and 31.9% in the RIF group. In the present study, patients with RIF exhibited higher frequencies of the VEGF variant genotypes and haplotypes, leading to an increased number of implantation failures, compared with controls.

Table II.

Baseline characteristics of patients with RIF and control subjects.

| Characteristic | Control subjects (n=218) | Patients with RIF (n=116) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 33.34±5.88 | 34.22±3.35 | 0.127 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.77±3.41 | 21.05±2.77 | 0.081 |

| Previous implantation failure (n) | NA | 4.75±2.29 | – |

| Live births (n) | 1.80±0.74 | NA | – |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 39.34±1.66 | None | – |

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | NA | 36.06±961 | – |

| FSH (mIU/ml) | NA | 8.60±4.29 | – |

| LH (mIU/ml) | NA | 4.86±2.31 | – |

| TSH (ng/ml) | NA | 2.28±1.45 | – |

| PRL (ng/ml) | NA | 12.78±6.17 | – |

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. RIF, recurrent implantation failure; NA, not applicable; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; PRL, prolactin.

Table III.

Genotype and haplotype frequencies of VEGF polymorphisms.

| A, Genotype frequencies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without RIF | With RIF | ||

| Genotype | Controls, n=218 (%) | Total RIFs, n=116 (%) | ≥4 RIFs, n=72 (%) |

| VEGF −2578CC | 112 (51.4) | 56 (48.3) | 33 (45.8) |

| VEGF −2578CA | 95 (43.6) | 49 (42.2) | 30 (41.7) |

| VEGF −2578AA | 11 (5.0) | 11 (9.5) | 9 (12.5) |

| HWE-P | 0.105 | 0.953 | 0.596 |

| VEGF −1154GG | 157 (72.0) | 78 (67.2) | 46 (63.9) |

| VEGF −1154GA | 53 (24.3) | 33 (28.4) | 22 (30.6) |

| VEGF −1154AA | 8 (3.7) | 5 (4.3) | 4 (5.6) |

| HWE-P | 0.197 | 0.533 | 0.532 |

| VEGF −634CC | 41 (18.8) | 12 (10.3) | 5 (6.9) |

| VEGF −634CG | 112 (51.4) | 56 (48.3) | 33 (45.8) |

| VEGF −634GG | 65 (29.8) | 48 (41.4) | 34 (47.2) |

| HWE-P | 0.554 | 0.461 | 0.424 |

| VEGF 936CC | 151 (69.3) | 78 (67.2) | 45 (62.5) |

| VEGF 936CT | 62 (28.4) | 37 (31.9) | 27 (37.5) |

| VEGF 936TT | 5 (2.3) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| HWE-P | 0.642 | 0.130 | 0.050 |

| B, Haplotype frequencies | |||

| Without RIF | With RIF | ||

| Haplotype | Controls (2n=436, %) | Total RIFs (2n=232, %) | ≥4 RIFs (2n=144, %) |

| VEGF −2578C/-1154G/-634C/936C | 183 (42.0) | 74 (31.9) | 40 (27.8) |

| VEGF −2578C/-1154G/-634C/936T | 6 (1.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| VEGF −2578C/-1154G/-634G/936C | 107 (24.5) | 68 (29.3) | 46 (31.9) |

| VEGF −2578C/-1154G/-634G/936T | 17 (3.9) | 16 (6.9) | 9 (6.3) |

| VEGF −2578C/-1154A/-634C/936C | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| VEGF −2578C/-1154A/-634C/936T | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| VEGF −2578C/-1154A/-634G/936C | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| VEGF −2578C/-1154A/-634G/936T | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) |

| VEGF −2578A/-1154G/-634C/936C | 4 (0.9) | 5 (2.2) | 3 (2.1) |

| VEGF −2578A/-1154G/-634G/936C | 23 (5.3) | 14 (6.0) | 8 (5.6) |

| VEGF −2578A/-1154G/-634G/936T | 27 (6.2) | 11 (4.7) | 8 (5.6) |

| VEGF −2578A/-1154A/-634G/936C | 43 (9.9) | 31 (13.4) | 20 (13.9) |

| VEGF −2578A/-1154A/-634G/936T | 20 (4.6) | 10 (4.3) | 9 (6.3) |

RIF, recurrent implantation failure; HWE, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Genetic susceptibility of single and multiple markers

The AORs for RIF prevalence according to the VEGF genotypes are provided in Table IV. The VEGF −2578AA genotype was associated with a significantly increased prevalence (≥4) of RIFs (AOR=2.77; 95% CI=1.10–7.02; P=0.031). The VEGF −634CG+GG genotype was associated with a significantly increased incidence of total RIF (AOR=2.03; 95% CI=1.02–4.05; P=0.044) and ≥4 RIFs (AOR=3.16; 95% CI=1.19–8.37; P=0.021). No statistically significant differences were observed between the control and RIF groups for any of the other genotypes.

Table IV.

AORs for RIF prevalence according to VEGF genotype and haplotype.

| A, VEGF genotypes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total RIFs | ≥4 RIFs | |||||||

| Genotype | Model | Reference type | AOR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted Pa | AOR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted Pa |

| VEGF −2578C>A | Additive | −2578CC | 1.21 (0.84–1.75) | 0.303 | 0.606 | 1.39 (0.91–2.12) | 0.131 | 0.262 |

| Dominant | −2578CC | 1.12 (0.71–1.75) | 0.637 | 0.764 | 1.23 (0.72–2.10) | 0.454 | 0.454 | |

| Recessive | −2578CC | 2.02 (0.85–4.83) | 0.113 | 0.226 | 2.77 (1.10–7.02) | 0.031 | 0.047 | |

| VEGF −1154G>A | Additive | −1154GG | 1.17 (0.78–1.75) | 0.461 | 0.615 | 1.34 (0.84–2.12) | 0.215 | 0.287 |

| Dominant | −1154GG | 1.22 (0.75–1.99) | 0.433 | 0.764 | 1.42 (0.81–2.50) | 0.225 | 0.427 | |

| Recessive | −1154GG | 1.15 (0.37–3.62) | 0.811 | 0.811 | 1.52 (0.44–5.25) | 0.504 | 0.504 | |

| VEGF −634C>G | Additive | −634CC | 1.56 (1.10–2.19) | 0.012 | 0.048 | 1.95 (1.28–2.98) | 0.002 | 0.008 |

| Dominant | −634CC | 2.03 (1.02–4.05) | 0.044 | 0.176 | 3.16 (1.19–8.37) | 0.021 | 0.084 | |

| Recessive | −634CC | 1.65 (1.03–2.65) | 0.037 | 0.148 | 2.10 (1.22–3.64) | 0.008 | 0.024 | |

| VEGF 936C>T | Additive | 936CC | 1.00 (0.64–1.56) | 0.995 | 0.995 | 1.15 (0.69–1.93) | 0.587 | 0.587 |

| Dominant | 936CC | 1.08 (0.66–1.75) | 0.764 | 0.764 | 1.33 (0.76–2.32) | 0.32 | 0.427 | |

| Recessive | 936CC | 0.32 (0.04–2.86) | 0.308 | 0.411 | NA | NA | NA | |

| B, VEGF haplotypes | ||||||||

| Total RIFs | ≥4 RIFs | |||||||

| Haplotype | Reference type | AOR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted Pa | AOR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted Pa | |

| VEGF −2578C/-1154G/-634C/936T | −2578C/-1154G/-634C/936C | 0.38 (0.04–3.26) | 0.378 | 0.504 | NA | NA | ||

| VEGF −2578C/-1154G/-634G/936C | −2578C/-1154G/-634C/936C | 1.59 (1.06–2.39) | 0.026 | 0.107 | 2.00 (1.23–3.26) | 0.006 | 0.042 | |

| VEGF −2578C/-1154G/-634G/936T | −2578C/-1154G/-634C/936C | 2.29 (1.10–4.79) | 0.027 | 0.107 | 2.38 (0.99–5.75) | 0.053 | 0.124 | |

| VEGF −2578A/-1154G/-634C/936C | −2578C/-1154G/-634C/936C | 3.09 (0.81–1.82) | 0.100 | 0.200 | 3.34 (0.72–15.55) | 0.124 | 0.174 | |

| VEGF −2578A/-1154G/-634G/936C | −2578C/-1154G/-634C/936C | 1.52 (0.74–3.12) | 0.253 | 0.405 | 1.60 (0.67–3.84) | 0.292 | 0.174 | |

| VEGF −2578A/-1154G/-634G/936T | −2578C/-1154G/-634C/936C | 1.02 (0.48–2.16) | 0.961 | 0.961 | 1.37 (0.58–3.24) | 0.475 | 0.341 | |

| VEGF −2578A/-1154A/-634G/936C | −2578C/-1154G/-634C/936C | 1.76 (1.03–3.00) | 0.040 | 0.107 | 2.11 (1.12–3.97) | 0.021 | 0.475 | |

| VEGF −2578A/-1154A/-634G/936T | −2578C/-1154G/-634C/936C | 1.20 (0.53–2.68) | 0.666 | 0.761 | 2.01 (0.85–4.74) | 0.113 | 0.074 | |

False discovery rate-adjusted P-value for multiple hypotheses testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence intervals; RIF, recurrent implantation failure; NA, not applicable; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor. AORs and P-values were adjusted by age and body mass index.

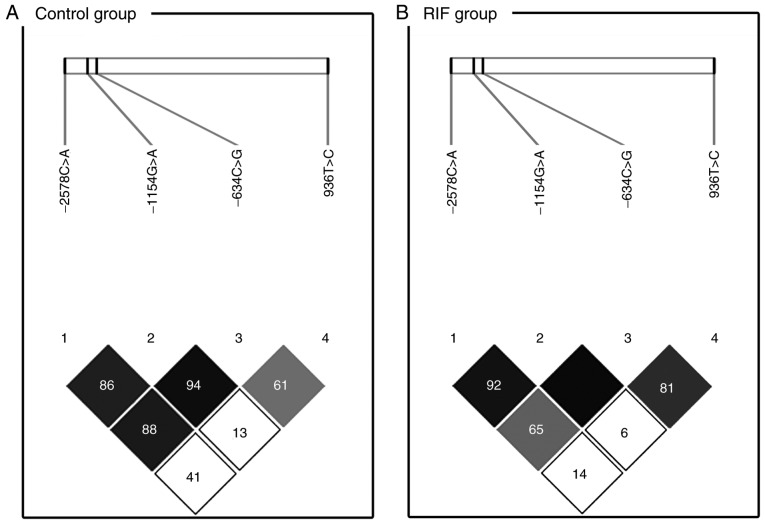

The linkage disequilibrium of the VEGF polymorphisms at loci −2578(rs699947)/-1154(rs1570360)/-634 (rs2010963)/936(rs3025039) in the RIF and control groups are detailed in Fig. 1. There was a clear linkage disequilibrium between loci −1154 and −634 (D'=0.945) and −2578 and −634 (D'=0.885) in the control group (Fig. 1A). Polymorphisms −1154G>A and −634G>C had a clear linkage disequilibrium in the RIF group (D'=1.000; Fig. 1B). The selected haplotypes with the four VEGF polymorphisms were constructed to determine if any specific haplotypes were associated with RIF prevalence (Table IV). The C-G-G-C (AOR=1.59; 95% CI=1.06–2.39; P=0.026 for total RIF and AOR=2.00; 95% CI=1.23–3.26; P=0.006 for ≥4 RIF), C-G-G-T (AOR=2.29; 95% CI=1.10–4.79; P=0.027 for total RIF) and A-A-G-C (AOR=1.76; 95% CI=1.03–3.00; P=0.040 for total RIF and AOR=2.11; 95% CI=1.12–3.97; P=0.021 for ≥4 RIF) haplotype frequencies of the VEGF −2578C>A, −1154G>A, −634C>G and 936C>T variants, respectively, were significantly different between the RIF and the control group.

Figure 1.

LD patterns of VEGF single nucleotide polymorphisms. The values in the squares denote LD between single markers. (A) Control subjects exhibited strong LD between loci VEGF −1154G>A (rs1570360) and −634C>G (rs2010963; D'=0.945), VEGF −2578C>A (rs699947) and −1154G>A (rs1570360; D'=0.863) and VEGF −2578C>A (rs699947) and −634C>G (rs2010963; D'=0.885). (B) Patients with recurrent implantation failure exhibited strong LD between loci VEGF −2578C>A (rs699947) and −1154G>A (rs1570360; D'=0.923) and between VEGF −1154G>A and −634C>G (D'=1.000). Dark squares indicate high r2 values and light squares indicate low r2 values. LD, linkage disequilibrium; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

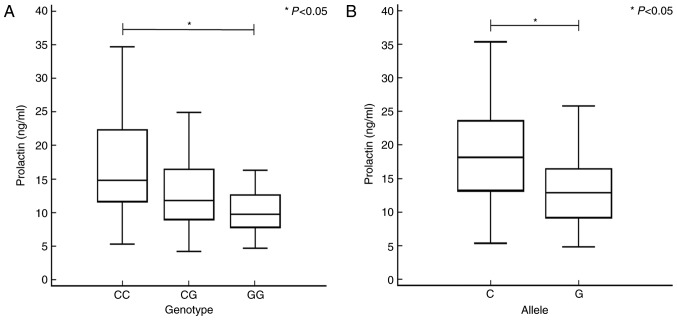

Differences in hormones according to VEGF polymorphisms in the RIF group

Possible associations between RIF and the serum level of PRL were examined. The results are presented in Fig. 2 according to VEGF gene polymorphisms. Patients with the VEGF −634GG genotype had significantly lower serum PRL levels compared with patients with the VEGF −634CC genotype (Fig. 2A). Additionally, patients with the VEGF −634G allele had significantly lower serum PRL levels compared with patients with the VEGF −634C allele (Fig. 2B). Levels of the other hormones investigated (E2, FSH, LH and TSH) were not significantly associated with the polymorphisms examined in the present study (Table V). Table VI summarizes the statistical power of genetic associations in the present case-control study. The analysis of VEGF −634C>G polymorphism was statistically significant when compared with the additive model (94.49%), dominant model (99.91%) and recessive model (94.79%) for AORs with RIF risk in total RIFs. In ≥4 RIFs, the statistical power of VEGF −634C>G polymorphism was strongly significant when compared with the additive model (99.25%), dominant model (100%) and recessive model (99.85%). In addition, the VEGF −2578C>A polymorphism was demonstrated to possess a greater statistical power than that of the recessive model (99.99%) in AORs of ≥4 RIFs.

Figure 2.

Association between differences in PRL levels and VEGF −634C>G in patients with recurrent implantation failure. Data was analyzed using one-way analysis of variance with a post-hoc Scheffé test for all pairwise comparisons or Student's t-test for each VEGF −634C>G genotype and allele, respectively. (A) PRL levels in the serum differed significantly (P<0.05) between patients with the VEGF −634CC [median (range): 14.81 (5.30–34.72)] and -GG [9.77 (4.73–17.40)] genotypes. (B) Patients with the VEGF −634G allele had significantly lower PRL levels compared with patients with the −634C allele. *P<0.05. PRL, prolactin; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Table V.

Differences in various reproduction-related endocrine parameters according to VEGF polymorphism in patients with RIF.

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | FSH (mIU/ml) | LH (mIU/ml) | PRL (ng/ml) | TSH (ng/ml) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Mean ± SD (n) | CV, % | Mean ± SD (n) | CV, % | Mean ± SD (n) | CV, % | Mean ± SD (n) | CV, % | Mean ± SD (n) | CV, % |

| VEGF −2578CC | 30.18±9.09 (11) | 30.1 | 7.92±3.96 (9) | 50 | 5.16±1.58 (8) | 30.6 | 12.81±5.11 (9) | 39.9 | 1.76±0.63 (9) | 35.8 |

| VEGF −2578CA | 34.39±24.95 (44) | 72.6 | 9.16±5.38 (40) | 58.7 | 4.49±2.18 (39) | 48.6 | 12.49±6.65 (40) | 53.2 | 2.25±1.22 (39) | 54.2 |

| VEGF −2578AA | 39.27±25.79 (43) | 65.7 | 8.21±3.07 (43) | 37.4 | 5.15±2.53 (41) | 49.1 | 13.03±6.03 (44) | 46.3 | 2.42±1.74 (43) | 71.9 |

| P-value | 0.449 | 0.535 | 0.41 | 0.926 | 0.47 | |||||

| C allele | 32.99±21.01 (66) | 63.7 | 8.78±4.96 (58) | 56.5 | 4.68±2.02 (55) | 43.2 | 12.59±6.13 (58) | 48.7 | 2.10±1.09 (57) | 51.9 |

| A allele | 37.62±25.42 (130) | 67.6 | 8.51±3.95 (126) | 46.4 | 4.94±2.42 (121) | 49 | 12.86±6.19 (128) | 48.1 | 2.37±1.59 (125) | 67.1 |

| P-value | 0.204 | 0.7 | 0.497 | 0.785 | 0.25 | |||||

| VEGF −1154GG | 28.14±9.95 (5) | 35.4 | 8.69±5.38 (5) | 61.9 | 4.61±1.47 (4) | 31.9 | 14.12±4.74 (5) | 33.6 | 1.89±0.71 (5) | 37.6 |

| VEGF −1154GA | 32.36±13.26 (28) | 41 | 8.45±4.61 (26) | 54.6 | 4.73±2.39 (26) | 50.5 | 12.46±6.16 (28) | 49.4 | 2.29±1.03 (27) | 45 |

| VEGF −1154AA | 38.26±28.04 (65) | 73.3 | 8.65±4.14 (61) | 47.9 | 4.93±2.34 (58) | 47.5 | 12.81±6.35 (60) | 49.6 | 2.31±1.66 (59) | 71.9 |

| P-value | 0.424 | 0.978 | 0.915 | 0.858 | 0.83 | |||||

| G allele | 31.25±12.38 (38) | 39.6 | 8.51±4.67 (36) | 54.9 | 4.70±2.18 (34) | 46.4 | 12.89±5.76 (38) | 44.7 | 2.19±0.96 (37) | 43.8 |

| A allele | 37.21±26.01 (158) | 69.9 | 8.62±4.20 (148) | 48.7 | 4.90±2.33 (142) | 47.6 | 12.75±6.27 (148) | 49.2 | 2.31±1.55 (145) | 67.1 |

| P-value | 0.171 | 0.898 | 0.664 | 0.896 | 0.649 | |||||

| VEGF −634CC | 44.80±36.38 (11) | 81.2 | 9.35±2.95 (10) | 31.6 | 5.60±2.98 (9) | 53.2 | 17.68±9.13 (10) | 51.6 | 2.37±1.78 (9) | 75.1 |

| VEGF −634CG | 36.72±19.73 (46) | 53.7 | 8.14±3.55 (48) | 43.6 | 4.87±2.23 (45) | 45.8 | 12.89±5.42 (46) | 42 | 2.24±1.62 (46) | 72.3 |

| VEGF −634GG | 32.97±24.74 (41) | 75 | 9.01±5.46 (34) | 60.6 | 4.64±2.25 (34) | 48.5 | 11.30±5.55 (37) | 49.1 | 2.32±1.15 (36) | 49.6 |

| P-value | 0.345 | 0.565 | 0.546 | 0.013 | 0.953 | |||||

| C allele | 39.33±25.91 (68) | 65.9 | 8.50±3.39 (68) | 39.9 | 5.08±2.43 (63) | 47.8 | 14.34±6.95 (66) | 48.5 | 2.27±1.64 (64) | 72.2 |

| G allele | 34.32±22.95 (128) | 66.9 | 8.65±4.74 (116) | 54.8 | 4.73±2.22 (113) | 46.9 | 11.91±5.51 (120) | 46.3 | 2.29±1.34 (118) | 58.5 |

| P-value | 0.166 | 0.814 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.956 | |||||

| VEGF 936CC | 37.27±27.93 (67) | 74.9 | 8.16±3.75 (61) | 46 | 5.00±2.41 (58) | 48.2 | 12.99±6.01 (63) | 46.3 | 2.41±1.61 (62) | 66.8 |

| VEGF 936CT | 33.76±12.61 (30) | 37.4 | 9.46±5.15 (31) | 54.4 | 4.59±2.11 (30) | 46 | 12.32±6.57 (30) | 53.3 | 2.02±1.01 (29) | 50 |

| VEGF 936TT | 24.00 (1) | – | – | – | – | |||||

| P-value | 0.712 | 0.169 | 0.437 | 0.627 | 0.238 | |||||

| C allele | 36.63±25.72 (164) | 70.2 | 8.42±4.08 (153) | 48.5 | 4.91±2.34 (146) | 47.7 | 12.86±6.09 (156) | 47.4 | 2.33±1.52 (153) | 65.2 |

| T allele | 33.15±12.43 (32) | 37.5 | 9.46±5.15 (31) | 54.4 | 4.59±2.11 (30) | 46 | 12.32±6.57 (30) | 53.3 | 2.02±1.01 (29) | 50 |

| P-value | 0.456 | 0.217 | 0.486 | 0.661 | 0.286 | |||||

RIF, recurrent implantation failure; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; PRL, prolactin; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; CV, coefficient of variation.

Table VI.

Statistical powers of genetic associations in the present case-control study.

| Total RIFs | ≥4 RIFs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Model | Reference type | AOR (95% CI) | Statistical power (%) | AOR (95% CI) | Statistical power (%) |

| VEGF −2578C>A | Additive | −2578CC | 1.21 (0.84–1.75) | 27.94 | 1.39 (0.91–2.12) | 58.78 |

| Dominant | −2578CC | 1.12 (0.71–1.75) | 14.7 | 1.23 (0.72–2.10) | 28.02 | |

| Recessive | −2578CC | 2.02 (0.85–4.83) | 99.98 | 2.77 (1.10–7.02) | 99.99 | |

| VEGF −1154G>A | Additive | −1154GG | 1.17 (0.78–1.75) | 24.42 | 1.34 (0.84–2.12) | 49.69 |

| Dominant | −1154GG | 1.22 (0.75–1.99) | 36.6 | 1.42 (0.81–2.50) | 64.89 | |

| Recessive | −1154GG | 1.15 (0.37–3.62) | 21.23 | 1.52 (0.44–5.25) | 80.35 | |

| VEGF −634C>G | Additive | −634CC | 1.56 (1.10–2.19) | 94.49 | 1.95 (1.28–2.98) | 99.25 |

| Dominant | −634CC | 2.03 (1.02–4.05) | 99.91 | 3.16 (1.19–8.37) | 100.00 | |

| Recessive | −634CC | 1.65 (1.03–2.65) | 94.79 | 2.10 (1.22–3.64) | 99.85 | |

| VEGF 936C>T | Additive | 936CC | 1.00 (0.64–1.56) | 5.0 | 1.15 (0.69–1.93) | 16.07 |

| Dominant | 936CC | 1.08 (0.66–1.75) | 8.38 | 1.33 (0.76–2.32) | 47.53 | |

| Recessive | 936CC | 0.32 (0.04–2.86) | 100.0 | NA | ||

AORs and P-values were adjusted by age and body mass index. AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; RIF, recurrent implantation failure; NA, not applicable; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Discussion

The present study evaluated the association between four functional VEGF SNPs (−2578C>A, −1154G>A, −634C>G and 936C>T) and the prevalence of RIF in Korean females. The results indicated that the VEGF −2578AA genotype, −634G allele and −2578C/-1154G/-634G/936C, −2578C/-1154G/-634G/936T and −2578A/-1154A/-634G/936C haplotypes may be genetic markers for susceptibility to RIF.

The −2578C>A and −1154G>A variants are located in the VEGF promoter region (26). The VEGF −2578CC and −1154GG genotypes appear to confer increased VEGF secretion compared with the presence of a minor allele (36,37). However, the functional effect of VEGF −634C>G is contested. Watson et al (15) and Hansen et al (38) proposed that the VEGF −634C allele was associated with the decreased production of VEGF, whereas Wongpiyabovorn et al (16) and Awata et al (39) reported that the VEGF −634G allele was associated with decreased VEGF production. These conflicting results are potentially due to the effect of haplotype combinations. Therefore, based on the VEGF haplotypes containing other VEGF SNPs, the effect of VEGF −634C>G should be examined further. It has previously been reported that there is an association between the haplotypes resulting from polymorphisms in the promoter region (−2578/-1154/-634) and VEGF expression (36). Lambrechts et al (36) reported that the −2578A/-1154A/-634G and −2578A/-1154G/-634G VEGF haplotypes were significantly correlated with decreased VEGF mRNA expression and plasma concentrations.

Among these polymorphisms, the mechanism of VEGF −2578C>A is well known (36,40,41). This SNP is in complete linkage with the deletion/insertion of an 18-bp fragment in the −2549 region and a construct containing the 18-bp deletion (linkage with the C allele) causing a 1.95-fold increase in transactivation (42). As evidence of the VEGF −1154G>A and −634C>G function is limited, the transcription factor binding sites containing these SNPs were predicted using P-Match. VEGF-1154G>A is contained within a predicted binding site for myeloid zinc finger-1 (MZF1) in which the MZF1 binding site is substituted for the Pax2 or Sp1 binding site by −1154A (prediction data attained using P-Match; gene-regulation.com). VEGF −634C>G is likewise identified within the predicted MZF1 or Pax2 binding site (prediction data attained using P-Match; gene-regulation.com), however, a change in the predicted transcription factor binding sites is not produced by the substitution.

In addition to VEGF, serum levels of the classical decidualization marker PRL should also be considered in association with decidualization of the endometrium. The present study revealed an association between the VEGF −634C>G polymorphism and plasma PRL levels. A previous study reported that VEGF rs3025039C>T was correlated with plasma PRL levels in polycystic ovary syndrome (43). A number of previous studies have also revealed that secreted PRL affects tissue vascularization at the lactation stage and present a role of PRL as a pro-angiogenic factor (44–48). Based on this, the current authors hypothesized that VEGF polymorphisms may affect the plasma PRL levels, however this hypothesis was not clearly confirmed or rejected through the experiments of the present study. Therefore, further studies are necessary to determine the potential association between VEGF polymorphisms and PRL levels.

Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that differences in PRL levels affect the formation of the placenta and decidualization of the endometrium following fertilization (44,49–52). PRL also regulates inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, TGF-β and IL-8) levels and immune system homeostasis in early pregnancy (53–55). Therefore, normal PRL levels are critical for maintaining a successful pregnancy. In addition, PRL regulates gonadal function and serves roles in steroidogenesis, formation of the corpus luteum and modulation of the effects of gonadotropins (55). PRL stimulates the process of ovulation, implantation and placental development (49–52,56). In addition, PRL stimulates the growth, development and metabolism of the fetus, serves key roles in the formation of the corpus luteum, decreases levels of sex steroids during the menstrual cycle and stimulates the production of milk during the postpartum period (57).

The present study had several limitations. Firstly, the serum VEGF levels in the participants were not measured. Although the association between VEGF polymorphisms and serum VEGF levels has been elucidated in other conditions (36,42), the data associated with RIF is limited. Secondly, it was not possible to explain the exact role of VEGF in the pathogenesis of RIF development. Accordingly, in future research an association between the VEGF polymorphisms and VEGF expression in the tissues in which implantation events occur, as opposed to serum concentrations, should be elucidated. VEGF expression occurs within biochemical pathways and is not the only risk factor for disorders associated with implantation and pregnancy maintenance. Therefore, the interactions between VEGF and other factors expressed during implantation are also potential risk factors. To overcome these constraints, further studies on the functional role of VEGF polymorphisms in the pathogenesis of RIF are required.

In conclusion, the −2578C>A, −1154G>A and −634C>G polymorphisms in the VEGF promoter region were associated with the occurrence of RIF. The results revealed an association between the VEGF −634C>G polymorphism and serum PRL levels. However, further studies of the VEGF promoter polymorphisms involving an independent randomized-controlled population are required to confirm these results. Additionally, the results of the present study warrant additional studies to elucidate the functional role of VEGF promoter polymorphisms in the RIF etiologies. Therefore, the present study indicates that the VEGF −2578AA genotype, −634G allele and −2578A/-1154A/-634G/936C haplotype may be utilized as biomarkers for patients with RIF. However, further studies are required to confirm this.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Korea Health Technology R&D Project from the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant no. HI15C1972010015).

References

- 1.Coughlan C, Ledger W, Wang Q, Liu F, Demirol A, Gurgan T, Cutting R, Ong K, Sallam H, Li TC. Recurrent implantation failure: Definition and management. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;28:14–38. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polanski LT, Baumgarten MN, Quenby S, Brosens J, Campbell BK, Raine-Fenning NJ. What exactly do we mean by ‘recurrent implantation failure’? A systematic review and opinion. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;28:409–423. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Margalioth EJ, Ben-Chetrit A, Gal M, Eldar-Geva T. Investigation and treatment of repeated implantation failure following IVF-ET. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:3036–3043. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan BK, Vandekerckhove P, Kennedy R, Keay SD. Investigation and current management of recurrent IVF treatment failure in the UK. BJOG. 2005;112:773–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valdes CT, Schutt A, Simon C. Implantation failure of endometrial origin: It is not pathology, but our failure to synchronize the developing embryo with a receptive endometrium. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei P, Yu FQ, Chen XL, Tao SX, Han CS, Liu YX. VEGF, bFGF and their receptors at the fetal-maternal interface of the rhesus monkey. Placenta. 2004;25:184–196. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Licht P, Russu V, Lehmeyer S, Wissentheit T, Siebzehnrehn E, Wildt L. Cycle dependency of intrauterine vascular endothelial growth factor levels is correlated with decidualization and corpus luteum function. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:1228–1233. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)02165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugino N, Kashida S, Takiguchi S, Nakamura Y, Kato H. Induction of superoxide dismutase by decidualization in human endometrial stromal cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6:178–184. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugino N, Kashida S, Karube-Harada A, Takiguchi S, Kato H. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors in human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle and in early pregnancy. Reproduction. 2002;123:379–387. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1230379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapiteijn K, Koolwijk P, van der Weiden RM, van Nieuw AG, Plaisier M, van Hinsbergh VW, Helmerhorst FM. Human embryo-conditioned medium stimulates in vitro endometrial angiogenesis. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1232–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben Ali Gannoun M, Al-Madhi SA, Zitouni H, Raguema N, Meddeb S, Ben Ali Hachena F, Mahjoub T, Almawi WY. Vascular endothelial growth factor single nucleotide polymorphisms and haplotypes in pre-eclampsia: A case-control study. Cytokine. 2017;97:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brogan IJ, Khan N, Isaac K, Hutchinson JA, Pravica V, Hutchinson IV. Novel polymorphisms in the promoter and 5′ UTR regions of the human vascular endothelial growth factor gene. Hum Immunol. 1999;60:1245–1249. doi: 10.1016/S0198-8859(99)00132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koukourakis MI, Papazoglou D, Giatromanolaki A, Bougioukas G, Maltezos E, Siviridis E. VEGF gene sequence variation defines VEGF gene expression status and angiogenic activity in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2004;46:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renner W, Kotschan S, Hoffmann C, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Pilger E. A common 936 C/T mutation in the gene for vascular endothelial growth factor is associated with vascular endothelial growth factor plasma levels. J Vasc Res. 2000;37:443–448. doi: 10.1159/000054076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson CJ, Webb NJ, Bottomley MJ, Brenchley PE. Identification of polymorphisms within the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) gene: Correlation with variation in VEGF protein production. Cytokine. 2000;12:1232–1235. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wongpiyabovorn J, Hirankarn N, Ruchusatsawat K, Yooyongsatit S, Benjachat T, Avihingsanon Y. The association of single nucleotide polymorphism within vascular endothelial growth factor gene with systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Int J Immunogenet. 2011;38:63–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2010.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng D, Hao Y, Zhou W, Ma Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor +936C/T, −634G/C, −2578C/A and −1154G/A polymorphisms with risk of preeclampsia: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su MT, Lin SH, Chen YC. Genetic association studies of angiogenesis- and vasoconstriction-related genes in women with recurrent pregnancy loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:803–812. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li YZ, Wang LJ, Li X, Li SL, Wang JL, Wu ZH, Gong L, Zhang XD. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphisms contribute to the risk of endometriosis: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 case-control studies. Genet Mol Res. 2013;12:1035–1044. doi: 10.4238/2013.April.2.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boudjenah R, Molina-Gomes D, Wainer R, Mazancourt P, Selva J, Vialard F. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) +405G/C polymorphism and its relationship with recurrent implantation failure in women in an IVF programme with ICSI. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29:1415–1420. doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9878-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodman C, Jeyendran RS, Coulam CB. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphism and implantation failure. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;16:720–723. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60487-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodman C, Jeyendran RS, Coulam CB. P53 tumor suppressor factor, plasminogen activator inhibitor and vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphisms and recurrent implantation failure. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:494–498. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vagnini LD, Nascimento AM, Canas Mdo C, Renzi A, Oliveira-Pelegrin GR, Petersen CG, Mauri AL, Oliveira JA, Baruffi RL, Cavagna M, Franco JG., Jr The relationship between vascular endothelial growth factor 1154G/A polymorphism and recurrent implantation failure. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24:533–537. doi: 10.1159/000437370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vagnini LD, Nascimento AM, Canas Mdo C, Renzi A, Oliveira-Pelegrin GR, Petersen CG, Mauri AL, Oliveira JB, Baruffi RL, Cavagna M, et al. The relationship between vascular endothelial growth factor 1154 G/A polymorphism and recurrent implantation failure. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24:533–537. doi: 10.1159/000437370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung YW, Kim JO, Rah H, Kim JH, Kim YR, Lee Y, Lee WS, Kim NK. Genetic variants of vascular endothelial growth factor are associated with recurrent implantation failure in Korean women. Reprod Biomed Online. 2016;32:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barch MJ, Knutsen T, Spurbeck JL. The AGT Cytogenetics Laboratory Manual. 3rd edition. Lippincott-Raven Publishers; New York, NY: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeon YJ, Choi YS, Rah HC, Choi Y, Yoon TK, Choi DH, Kim NK. The reduced folate carrier-1 (RFC1 696T>C) polymorphism is associated with spontaneously aborted embryos in Koreans. Genes Genom. 2011;33:223–228. doi: 10.1007/s13258-011-0016-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lockshin MD, Kim M, Laskin CA, Guerra M, Branch DW, Merrill J, Petri M, Porter TF, Sammaritano L, Stephenson MD, et al. Prediction of adverse pregnancy outcome by the presence of lupus anticoagulant, but not anticardiolipin antibody, in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2311–2318. doi: 10.1002/art.34402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Middeldorp S, van Hylckama Vlieg A. Does thrombophilia testing help in the clinical management of patients? Br J Haematol. 2008;143:321–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi DH, Kim EK, Kim KH, Lee KA, Kang DW, Kim HY, Bridges P, Ko CM. Expression pattern of endothelin system components and localization of smooth muscle cells in the human pre-ovulatory follicle. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:1171–1180. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabir S, Shahriar M, Kabir ANMH, Uddin MG. High salt SDS-based method for the direct extraction of genomic DNA from three different gram-negative organisms. CDR J. 2006;1:57–64. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong EP, Park JW, Suh JG, Kim DH. Effect of interactions between genetic polymorphisms and cigarette smoking on plasma triglyceride levels in elderly Koreans: The hallym aging study. Genes Genom. 2015;37:173–181. doi: 10.1007/s13258-014-0234-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Liu C, Xu K, Chen J. Association between PNPLA3 rs738409 polymorphism and hepatocellular carcinoma risk: An updated meta-analysis. Genes Genom. 2016;38:831–839. doi: 10.1007/s13258-016-0428-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chekmenev DS, Haid C, Kel AE. P-Match: Transcription factor binding site search by combining patterns and weight matrices. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W432–W437. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao D, Jin C, Ren M, Lin C, Zhang X, Zhao N. The expression of Gli3, regulated by HOXD13, may play a role in idiopathic congenital talipes equinovarus. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:142. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lambrechts D, Storkebaum E, Morimoto M, Del-Favero J, Desmet F, Marklund SL, Wyns S, Thijs V, Andersson J, van Marion I, et al. VEGF is a modifier of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice and humans and protects motoneurons against ischemic death. Nat Genet. 2003;34:383–394. doi: 10.1038/ng1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shahbazi M, Fryer AA, Pravica V, Brogan IJ, Ramsay HM, Hutchinson IV, Harden PN. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphisms are associated with acute renal allograft rejection. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:260–264. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V131260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hansen TF, Spindler KG, Lorentzen KA, Olsen DA, Andersen RF, Lindebjerg J, Brandslund I, Jakobsen A. The importance of −460 C/T and +405 G/C single nucleotide polymorphisms to the function of vascular endothelial growth factor A in colorectal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136:751–758. doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0714-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Awata T, Inoue K, Kurihara S, Ohkubo T, Watanabe M, Inukai K, Inoue I, Katayama S. A common polymorphism in the 5′-untranslated region of the VEGF gene is associated with diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51:1635–1639. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amoli MM, Amiri P, Alborzi A, Larijani B, Saba S, Tavakkoly-Bazzaz J. VEGF gene mRNA expression in patients with coronary artery disease. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:8595–8599. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Almodovar Ruiz C, Lambrechts D, Mazzone M, Carmeliet P. Role and therapeutic potential of VEGF in the nervous system. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:607–648. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang B, Cross DF, Ollerenshaw M, Millward BA, Demaine AG. Polymorphisms of the vascular endothelial growth factor and susceptibility to diabetic microvascular complications in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2003;17:1–6. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8727(02)00181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ben Salem A, Megdich F, Kacem O, Souayeh M, Hachani Ben Ali F, Hizem S, Janhai F, Ajina M, Abu-Elmagd M, Assidi M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGFA) gene variation in polycystic ovary syndrome in a Tunisian women population. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:748. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corbacho AM, De La Escalera Martínez G, Clapp C. Roles of prolactin and related members of the prolactin/growth hormone/placental lactogen family in angiogenesis. J Endocrinol. 2002;173:219–238. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1730219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldhar AS, Vonderhaar BK, Trott JF, Hovey RC. Prolactin-induced expression of vascular endothelial growth factor via Egr-1. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2005;232:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malaguarnera L, Imbesi RM, Scuto A, D'Amico F, Licata F, Messina A, Sanfilippo S. Prolactin increases HO-1 expression and induces VEGF production in human macrophages. J Cell Biochem. 2004;93:197–206. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seow KM, Lee WL, Wang PH. A challenge in the management of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;55:157–158. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim YR, Hong SH. Gender-specific association of polymorphisms in the 5′-UTR and 3′-UTR of VEGF gene with hypertensive patients. Genes Genom. 2015;37:551–558. doi: 10.1007/s13258-015-0284-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tenorio Fd, Simões Mde J, Teixeira VW, Teixeira ÁA. Effects of melatonin and prolactin in reproduction: Review of literature. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2015;61:269–274. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.61.03.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adams NR, Vasquez YM, Mo Q, Gibbons W, Kovanci E, DeMayo FJ. WNK lysine deficient protein kinase 1 regulates human endometrial stromal cell decidualization, proliferation and migration in part through mitogen-activated protein kinase 7. Biol Reprod. 2017;97:400–412. doi: 10.1093/biolre/iox108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu J, Berga SL, Zou W, Yook DG, Pan JC, Andrade AA, Zhao L, Sidell N, Bagchi IC, Bagchi MK, Taylor RN. IL-1β inhibits connexin 43 and disrupts decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells through ERK1/2 and p38 MAP kinase. Endocrinology. 2017 Sep 11; doi: 10.1210/en.2017-00495. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pavone ME, Malpani S, Dyson M, Bulun SE. Altered retinoid signaling compromises decidualization in human endometriotic stromal cells. Reproduction. 2017;154:107–116. doi: 10.1530/REP-16-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jikihara H, Handwerger S. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits the synthesis and release of human decidual prolactin. Endocrinology. 1994;134:353–357. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.1.8275950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garzia E, Borgato S, Cozzi V, Doi P, Bulfamante G, Persani L, Cetin I. Lack of expression of endometrial prolactin in early implantation failure: A pilot study. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1911–1916. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shirota M, Banville D, Ali S, Jolicoeur C, Boutin JM, Edery M, Djiane J, Kelly PA. Expression of two forms of prolactin receptor in rat ovary and liver. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:1136–1143. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-8-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bashir ST, Ishak GM, Gastal MO, Roser JF, Gastal EL. Changes in intrafollicular concentrations of free IGF-1, activin A, inhibin A, VEGF, estradiol and prolactin before ovulation in mares. Theriogenology. 2016;85:1491–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perks CM, Newcomb PV, Grohmann M, Wright RJ, Mason HD, Holly JM. Prolactin acts as a potent survival factor against C2-ceramide-induced apoptosis in human granulosa cells. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2672–2677. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]