Abstract

Purpose

This report aims at expanding the current knowledge of retinal microanatomy in children with incontinentia pigmenti using hand-held spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SDOCT).

Methods

We reviewed OCT scans from seven children (4 weeks–13 years) obtained either in the clinic or during an examination under anesthesia. The scans were analyzed for anatomical changes in the outer and inner retina, by certified graders. Medical records were assessed for systemic findings.

Results

We observed abnormal retinal findings unilaterally in three children. We found inner and outer retinal thinning temporally in two participants. This thinning was present prior to and persisted after treatment. One child showed a distorted foveal contour and significant retinal thickening secondary to dense epiretinal membrane and vitreomacular traction. All other children had normal retinae.

Conclusion

Hand-held SDOCT imaging of the retina has brought to light additional retinal structural defects that were not previously reported or visualized via routine clinical ophthalmic examination including retinal photography. Despite a normal foveal structure and visual acuity, we identified inner and outer retinal thinning on SDOCT which may benefit from future functional assessment such as visual field testing.

Keywords: retina, structural abnormality, Incontinentia pigmenti, children, optical coherence tomography, ocular findings

Introduction

First described by Garrod1 in 1906, incontinentia pigmenti (IP), also known as Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome, is an X-linked dominant inherited disease mostly seen in females and fatal in males. It has an incidence of 1 in every 40,000 newborns. IP occurs due to mutations in IKBKG/NEMO gene, which are responsible for impaired signaling of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), a critical transcription factor that upregulates the immune system and prevents cell death.2 This disease manifests at birth or early childhood, and is characterized by skin, dental, neurological and ocular abnormalities.3, 4 The ocular abnormalities primarily manifest in the retina, including vascular occlusion, neovascularization, hemorrhages, foveal abnormalities and retinal detachments.2 It has been postulated that pigmentary abnormality may affect the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) leading to retinal detachment.5–8

In the recent past, hand-held spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SDOCT) has been optimized for use in pediatric ophthalmology to visualize the retinal cross-sectional microstructures in infants9, 10 in the intensive care nursery, and in toddlers and older children in both the clinic and operating room. In 2015, Basilus et al. published the first report on OCT findings in IP in four children under 5 years of age.11 The present report adds additional reports of microanatomical changes observed in seven children with IP by SDOCT.

Methods

Data Collection

This retrospective analysis was of infants and children from a prospective OCT imaging study approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. A parent of each participant in the study provided informed consent for imaging and access to medical records. The SDOCT images were selected from an existing database of research imaging of pediatric participants, imaged with the portable handheld SDOCT system (Bioptigen Inc., Research Triangle Park, North Carolina). Scans were typically captured of the optic nerve and macula in each eye during examination under anesthesia or in clinic. The scans with the best image quality were selected for analysis. Funduscopic photographs and fluorescein angiography (FA) if available were obtained from the RetCam wide-field digital imaging system (Clarity Medical Systems Inc., Pleasanton, California). Ocular information such as best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), presence of strabismus and amblyopia, treatment history and systemic information, including genetic testing and magnetic resonance imaging scans, were extracted from the medical records and clinical research forms.

For this analysis we identified participants by reviewing our research database for diagnoses associated with “incontinentia pigmenti.” All eligible participants had either a confirmed genetic test for IKBKG/NEMO gene or a positive skin biopsy. Demographics were recorded from all the participants.

Image Analysis

Three certified graders (SM, DT, and XC) analyzed the OCT scans for qualitative and quantitative features. The SDOCT images were evaluated for foveal hypoplasia, presence and the development of retinal layers; description and disruption of layers and the presence of photoreceptor inner segment or ellipsoid zone (EZ) at the fovea. Quantitative measures included central foveal thickness (CFT) measured from inner limiting membrane (ILM) to inner RPE, fovea parafoveal (FP) ratio by measuring the parafoveal thickness 1000um from the fovea and dividing it by CFT, EZ height measured from the EZ to RPE at the fovea, and sub-foveal choroidal thickness (SFCT), were all assessed on OsiriX v4.1.12 software (Pixmeo, Bernex, Switzerland). We compared CFT and EZ height in eyes with and without peripheral vascular changes or other retinal thickness abnormalities.

Results

OCT images of 14 eyes of seven patients between the ages of 4 weeks to 13 years were analyzed. The clinical and OCT findings of each participant were summarized below. The quantitative measurements of the 7 participants are enumerated in Table 1 along with relative severity of IP retinal vascular changes. The CFT varied between the two eyes in most of the participants, with an interocular difference ranging from 9–22 μm.

Table 1.

Summary of the central foveal thickness (CFT): measured from inner limiting membrane to inner retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), ellipsoid zone (EZ) height measured from the EZ to RPE at the fovea, and the subfoveal choroidal thickness of each participant at the first visit. The variation of thickness between the right and the left eye was independent of any structural macular changes visualized on optical coherence tomography. The scale for severity of of Incontinentia pigmenti (IP) was based of the clinical findings with 0=Clinically normal retina, 1=Peripheral non-perfusion requring no treatment, 2=Areas of non-perfusion requiring treatment, 3=Retinal detachment

| Patient No | Age | Right eye (in μm) | Left eye (in μm) | Severity of IP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFT | EZ height | Choroid | CFT | EZ height | Choroid | |||

| 1 | 1 month | 201 | 75 | 416 | 182 | 76 | 403 | 2 |

| 2 | 7 months | 146 | 56 | 323 | 133 | 66 | 314 | 2 |

| 3 | 13 years | 244 | 83 | 393 | 252 | 69 | U | 3 |

| 4 | 20 months | 219 | 79 | U | 209 | 93 | 370 | 1 |

| 5 | 9 months | 144 | 80 | 292 | 153 | 67 | 277 | 0 |

| 6 | 9 months | 121 | 70 | 488 | 137 | 76 | 563 | 1 |

| 7 | 23 months | 140 | 73 | 308 | 162 | 68 | 320 | 0 |

Case 1

This patient was first examined at 4 weeks of age. The diagnosis of IP was confirmed based on skin biopsy. Her genetic testing was negative for mutations in the NEMO gene. She presented with a positive family history for IP wherein, her father, despite normal male karyotype, has IP, where male lethality is expected. Her skin findings included discrete areas of Blaschkcoid grayish hyperpigmentation of the distal lower extremities. At 1.8 years of age, she presented with focal neurological deficits - slurred speech and tongue deviation. MRI findings suggested a small cystic lesion the parietal lobe consistent with a perinatal insult. Her retinal findings included a speck of pigment inferior to the optic nerve in the left eye with early termination of temporal and inferior peripheral retinal vasculature confirmed by fluorescein angiography (FA) findings. She underwent laser photocoagulation of the avascular peripheral region in the left eye at 6 months of age.

OCT Findings

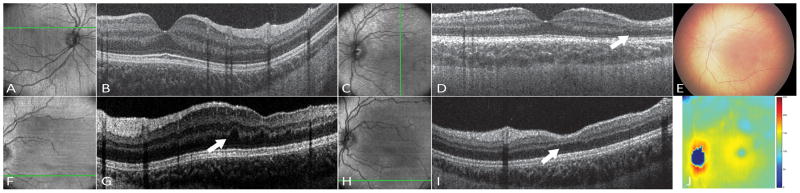

The macular OCT volume of the left eye showed areas of thinning of both outer and inner retinal layers, inferior and temporal to the fovea. The inner retinal thinning was observed to be more confluent, while the outer retinal layer thinning, which mainly involved the outer plexiform layer (OPL) was localized to a few scattered small areas only (Figure 1). There were no RPE abnormalities or increased OCT signal into the choroid at these sites. These findings were consistent over 5 clinical visits at ages 1 month, 2 months, 6 months, 1.2 years and 2.5 years. Interestingly, contrary to a previous report that the retinal thinning was observed after laser photocoagulation,11 this patient showed thinning of the retinal layers at the first visit at 1 month of age prior to laser treatment. These findings were stable for years after laser treatment, indicating that peripheral laser photocoagulation did not affect inner or outer macular retinal thinning. The right eye appeared normal. The photoreceptor complex appeared normal in both eyes, and her visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes on Snellen chart at age 3 years.

Figure 1.

Case 2

This patient was referred to the pediatric retina clinic for a possible tractional retinal detachment associated with the diagnosis of IP confirmed by skin biopsy at 6 months of age. She had a history of bullous skin eruptions at birth, which appeared as hyperpigmented macules on examination. Retinal examination of the right eye revealed dragged vessels to the temporal periphery, a flat macula, and a peripheral temporal tractional retinal detachment with pre-retinal hemorrhage and neovascularization at the inferior border. FA showed areas of temporal non-perfusion with neovascularization in the right eye. The left eye appeared normal on both fluorescein and clinical examination, except for a small hypopigmented spot inferotemporal to the macula. She underwent laser photocoagulation in the right eye at 7 months of age.

OCT Findings

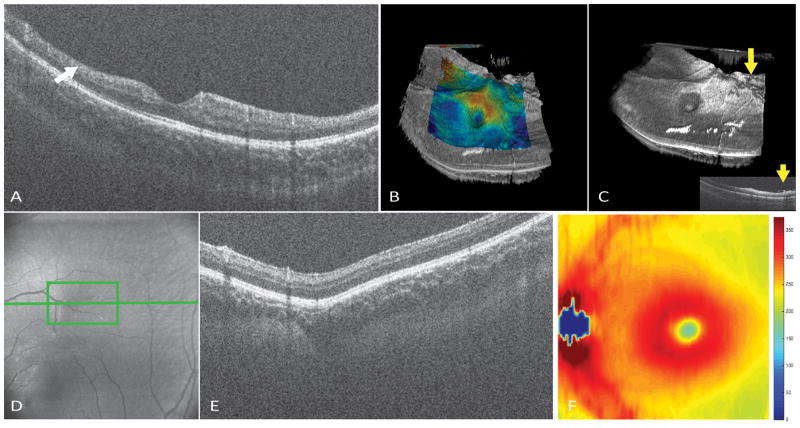

Hand-held SDOCT imaging of the right eye showed diffuse inner retinal thinning temporally in the parafoveal region (Figure 2). The apparent thickening of the retina due to dragging of vessels was not visualized due to the peripheral location. Similar to the previous participant, the retinal thinning was observed prior to laser photocoagulation and without RPE abnormalities or increased OCT signal into the choroid (Figure 3). No outer retinal layer defect was observed. The left eye showed a small choroidal excavation around the location of the hypo-pigmented spot (Figure 2). We observed pre-retinal tissue around the superior and inferior arcade, not detected on FA.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Case 3

This 11-year-old girl was referred for retina consult for possible Coats disease or familial exudative vitreoretinopathy. She was later confirmed by genetic testing as harboring a mosaic deletion of the IKBKG gene. On retinal examination, the right eye showed a flat macula and temporal areas of peripheral nonperfusion. The left eye showed vitreous hemorrhage inferiorly, and temporal dragging of vessels and macula. Peripheral exam showed retinal detachment in the temporal quadrant with extensions into the superior and inferior quadrant with peripheral nonperfusion. FA of the right eye showed peripheral nonperfusion temporally. The left eye showed non-perfusion in all the quadrants with active superior and temporal leakage. She underwent pars plana vitrectomy with epiretinal membrane peeling in the left eye and laser photocoagulation in both eyes.

OCT Findings

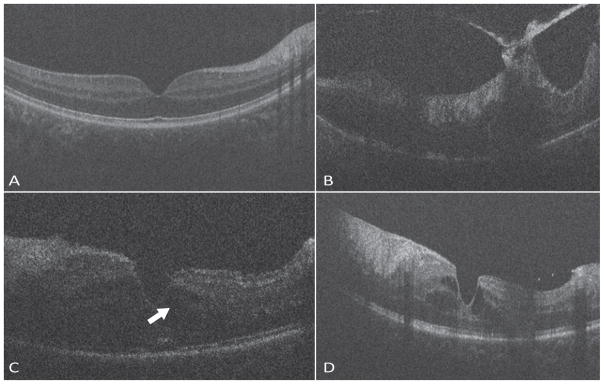

OCT of the right eye showed a normal macula. Pre-operatively, left eye showed a distorted macula with dense epiretinal membrane and vitreomacular traction, with significant retinal nerve fiber layer thickening, cystoid spaces in the inner plexiform and inner nuclear layers. The outer retinal layers seemed intact. Post-operative follow-up OCT revealed an improved foveal contour with residual intraretinal cysts (Figure 4). Two years after surgery the visual acuity improved to 20/80 from preoperative acuity of 20/250. No obvious retinal thinning was observed in either eye.

Figure 4.

Cases 4 & 5

A 4-year-old patient had a diagnosis of IP with negative genetic testing for mutations in the IKBKG gene. No heterozygosity was found by genetic sequencing, raising the possibility that there could be deletion of one copy of the NEMO gene. She had eczematoid, raised, lichenified rash on the inner aspect of the right upper arm and ridged nail in the thumb. Her mother and brother have a history of eczema and her mother additionally has abnormally-shaped teeth. The participant’s ophthalmic findings included small peripheral temporal areas of non-perfusion without leakage on fluorescein angiogram in both eyes.

A 9-month-old patient with a diagnosis of IP, confirmed by biopsy had vesicles located on the arms, legs, feet and trunk. She has had repeated admissions in the hospital due to failure to thrive, and had a gastrostomy tube placed. Her magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was normal. Both her right and left eye appeared to have a normal optic nerve and macula with some amount of subtle RPE pigmentary granularity. The retina was well-vascularized by examination and on FA.

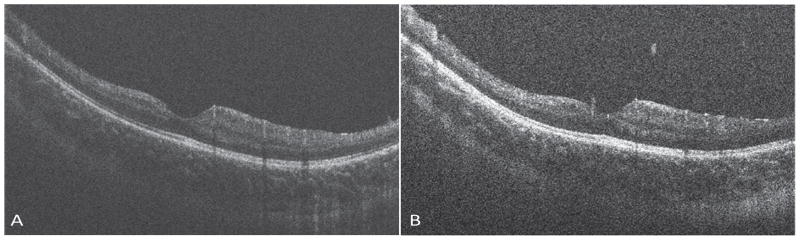

OCT Findings

The macular SDOCT imaging of both right and left eye appeared normal in these patients.

Cases 6 & 7

Two sisters, presenting for pediatric retinal evaluation at 9- and 23-months of age, respectively, and had positive genetic testing for IP. Their mother has IP and had a history of congenitally missing teeth treated with dental implants. She did not have any ocular or neurological abnormality.

Both sisters had vesicular and verrucous hyperkeratotic papules across both extremities, bilaterally, with linear configuration, following the lines of Blascho. Their retinaes both appeared normal and vessels extending up to the periphery. The 9 month old, however, had subtle pigment changes in the temporal macula in both eyes and what one physician thought was a slightly smaller optic nerve. In both the girls, the funduscopic images were consistent with the indirect ophthalmoscopic examination and FA did not show any leakage or vascular abnormalities.

OCT Findings

Both the girls had a normal looking optic nerve and macular anatomy, with no evidence of macular edema, nerve fiber layer defect or retinal thinning. The left eye of the 9-month old girl had a hyloid remnant visible over the optic nerve.

Discussion

Since the first report of IP in 1906, there have been a number of reports on ocular abnormalities found in IP. Carney3 and Minic12 summarized these findings in the world statistical report and a meta-analysis from 1906 to 2010. Reported eye manifestations of IP are diverse, and include amaurosis, strabismus and nystagmus, retinal anomalies such as retinal detachment, retinal vascular abnormalities (hemorrhage, neovascularization, avascularity of the retina), retinal pigment epithelium abnormalities and lens changes.2, 3, 5, 6, 8 The first report of the use of SDOCT imaging in IP11 in 2015 has tremendously increased our insight into structural abnormalities in the retina that are not visualized during a routine ophthalmic examination. However, little is known about the pathogenesis of these retinal anomalies. Mensheha-Manhart et al. believed the abnormality begins at the RPE leading to retinal changes with dysplasia and resulting in retinal detachment.5 On the other hand, primary arterial insufficiency13 and retinal ischemia leading to the synthesis of angiogenic factor14 was also hypothesized. Retinal changes have also been attributed to mutations in a gene on the X-chromosome leading to impairment of proteins required for cell differentiation.15 Due to the mechanism of X-chromosome inactivation, depending on when the X-inactivation occurred, larger or smaller areas are affected.

Similar to those reported by Basilius et al11, we visualized inner retinal layer thinning in 2 of our participants. Both children showed extensive areas of peripheral retinal non-perfusion. This leads us to believe that this retinal thinning may be consistent with a primary vascular defect with secondary neuronal involvement. Interestingly, we also observed outer retinal layer involvement, specifically in the OPL, with thinning in localized areas, which has not been previously reported. This could result from defective development of certain deeper vessels during retinal vascularization. Intriguingly, this thinning of the retina was stable over time from age 1 month to age 2.5 years in participant 1, before and after peripheral laser photocoagulation. The chronicity of these defects and stability over time indicate a non-progressive lesion that likely occurred at a particular time point during development. None of our participants showed foveal involvement and the visual acuity was 20/20 in all eyes except for the left eye of participant 3 which underwent vitrectomy and membrane peeling. The range of CFT, EZ height were comparable to published normative data for these ages.16 However, these findings of stable non-foveal retinal thinning also raise the possibility that despite 20/20 optotype visual acuity, subtle visual functional abnormalities may be present and delineated by future visual field testing and microperimetry testing. In addition both we and Basilius et al11 failed to find RPE abnormalities associated with such areas of thinning. Thus, we postulate that, as proposed by Goldberg et al,4 the neural tissue changes in the retina are secondary to vascular events and not secondary to abnormalities originating in the RPE.

One of the participants had temporal thinning of the retina and a brain magnetic resonance imaging showing a cystic lesion in the parietal lobe. However, its relation to the retinal thinning cannot be established. Basilius et al. report thin corpus callosum and immature myelination in a child with inner retinal thinning, both of which they noted are consistent with IP.11 These two cases raise the possibility of eye and brain association with neurovascular changes in IP.

Hand-held SDOCT imaging of the retina has brought to light additional retinal structural defects that were previously unreported and not visualized via routine clinical ophthalmic examination including retinal photography. Despite a normal foveal structure and visual acuity, functional assessment such as visual field testing (when children reach an age at which they could participate) may identify visual defects in children with IP, particularly in the corresponding areas of OCT-identified inner and outer retinal thinning. The observation that the fellow eye was normal in all participants with some form of ocular pathology, points towards a mosaic pattern of disease presentation. OCT imaging in these children will help identify microstructural retinal abnormalities and recognize changes not appreciable on other modalities of testing that may affect non-central visual function.

Summary Statement.

Children with incontinentia pigmenti showed abnormal retinal thinning of both the inner and outer retinal layers on optical coherence tomography.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The Hartwell Foundation; The Andrew Family Charitable Foundation; Research to Prevent Blindness; Retina Research Foundation; Grant Number 1UL1RR024128-(NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the resonsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. The sponsors or funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Toth recieves royalties through her university from Alcon and research support from Bioptigen and Genentech. She also has unlicened patents pending in OCT imaging and analysis. Dr. Fredman is a scientific consultant to Pfizer, Inc and Inotek, Inc. No other authors have financial disclosures. No authors have a proprietary interest in the current study.

References

- 1.Garrod AE. Peculiar pigmentation of the skin of an infant. Transactions of the Clinical Society of London. 190629:216. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swinney CC, Han DP, Karth PA. Incontinentia Pigmenti: A Comprehensive Review and Update. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46(6):650–657. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20150610-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carney RG. Incontinentia pigmenti. A world statistical analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112(4):535–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg MF. The blinding mechanisms of incontinentia pigmenti. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1994;92:167–176. discussion 176–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mensheha-Manhart O, Rodrigues MM, Shields JA, Shannon GM, Mirabelli RP. Retinal pigment epithelium in incontinentia pigmenti. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;79(4):571–577. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90794-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain RB, Willetts GS. Fundus changes in incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome): a case report. Br J Ophthalmol. 1978;62(9):622–626. doi: 10.1136/bjo.62.9.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahi J, Hungerford J. Early diagnosis of the retinopathy of incontinentia pigmenti: successful treatment by cryotherapy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74(6):377–379. doi: 10.1136/bjo.74.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott JG, Friedmann AI, Chitters M, Pepler WJ. Ocular changes in the Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome (Incontinentia pigmenti) Br J Ophthalmol. 1955;39(5):276–282. doi: 10.1136/bjo.39.5.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabrera MT, Maldonado RS, Toth CA, et al. Subfoveal fluid in healthy full-term newborns observed by handheld spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(1):167–175. e163. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maldonado RS, Izatt JA, Sarin N, et al. Optimizing hand-held spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging for neonates, infants, and children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(5):2678–2685. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basilius J, Young MP, Michaelis TC, Hobbs R, Jenkins G, Hartnett ME. Structural Abnormalities of the Inner Macula in Incontinentia Pigmenti. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(9):1067–1072. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minic S, Obradovic M, Kovacevic I, Trpinac D. Ocular anomalies in incontinentia pigmenti: literature review and meta-analysis. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2010;138(7–8):408–413. doi: 10.2298/sarh1008408m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishimura M, Oka Y, Takagi I, Yamana T, Kitano A. The clinical features and treatment of the retinopathy of Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome (incontinentia pigmenti) Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1980;24:310–319. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown CA. Incontinentia pigmenti: the development of pseudoglioma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72(6):452–455. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.6.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catalano RA, Lopatynsky M, Tasman WS. Treatment of proliferative retinopathy associated with incontinentia pigmenti. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;110(6):701–702. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee H, Purohit R, Patel A, et al. In Vivo Foveal Development Using Optical Coherence Tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(8):4537–4545. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]