Abstract

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC), a tumor derived from the neural crest, occurs either sporadically or as the dominant component of the type 2 multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes, MEN2A and MEN2B. The discovery that mutations in the RET protooncogene cause hereditary MTC was of great importance, since it led to the development of novel methods of diagnosis and treatment. For example, the detection of a mutated RET allele in family members at risk for inheriting MEN2A or MEN2B signaled that they would develop MTC, and possibly other components of the syndromes. Furthermore, the detection of a mutated allele created the opportunity, especially in young children, to remove the thyroid before MTC developed, or while it was confined to the gland. The discovery also led to the development of molecular targeted therapeutics (MTTs), mainly tyrosine kinase inhibitors, which were effective in the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic MTC. While responses to MTTs are often dramatic, they are highly variable, and almost always transient, because the tumor cells become resistant to the drugs. Clinical investigators and the pharmaceutical industry are focusing on the development of the next generation of MTTs, which have minimal toxicity and greater specificity for mutated RET.

Introduction

The description of MEN2A is often attributed to Sipple, who in 1961 reported a patient with a pheochromocytoma and cancer of the thyroid gland.(Sipple 1961) In reviewing the literature, he found 537 reports of pheochromocytoma and 27 associated malignancies, 6 of which were thyroid cancers. The thyroid cancer in Sipple’s patient was described as a poorly differentiated follicular adenocarcinoma, which is understandable, considering that the publication describing medullary thyroid carcinoma occurred only18 months earlier, and many pathologists were unaware of it.(Hazard, et al. 1959) Also, it would be another 7 years before Steiner and associates described a family with medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC), pheochromocytoma (PHEO), hyperparathyroidism (HPTH), and Cushing’s syndrome.(Steiner, et al. 1968) They suggested that “the entity characterized by tumors of the pituitary, parathyroids, and pancreas be designated multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, and that the entity characterized by the occurrence of pheochromocytoma, medullary thyroid carcinoma, and parathyroid tumors be designated multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2”.(Steiner et al. 1968; Wermer 1954) Therefore, the first publication describing MEN2A was clearly that of Steiner and associates, although earlier publications, including that of Sipple (and the subsequent report that the relatives of his patient had MEN2A) were evidence that the syndrome had existed for some time, but was not recognized as such.(Hughes 1996; Neumann, et al. 2007; Sipple 1961; Sipple 1984; Telenius-Berg, et al. 1984). In 1966 two years prior to Steiner’s report, Williams and Pollack described 2 patients with MTC, PHEOs, ganglioneuromatosis of the aerodigestive tract, and an unusual physical appearance.(Williams and Pollock 1966) The syndrome was thought to be allied to von Recklinghausen’s disease, but it was recognized subsequently as being similar to MEN2A and was named MEN2B. Farndon and associates described familial medullary thyroid carcinoma (FMTC), a syndrome distinguished by the presence of hereditary MTC, but none of the extrathyroidal manifestations of MEN2A.(Farndon, et al. 1986) As additional families were studied over subsequent decades investigators concluded that FMTC was a variant of MEN2A.(Wells, et al. 2015) Two other conditions occasionally occur in association with MEN2A: cutaneous lichen amyloidosis (CLA), and Hirschsprung’s disease (HD).(Amiel, et al. 2008; Gagel, et al. 1989; Nunziata, et al. 1989; Sijmons, et al. 1998)

The American Thyroid Association’s Task Force to revise the management guidelines for MTC proposed 4 variants of MEN2A: Classical MEN2A; characterized by MTC, PHEOs, and HPTH, MEN2A and CLA, MEN2A and HD, and FMTC.(Wells et al. 2015) Classic MEN2A is characterized by complete penetrance but variable expressivity, in that virtually all patients develop MTC, but PHEOs and HPTH occur less frequently, often depending on the presence of a specific RET codon mutation. Also, MEN2A and CLA, and MEN2A and HD are almost always associated with specific RET codon mutations. The presentation of MEN2B is more uniform in that all patients develop MTC, ganglioneuromatosis, and the typical phenotype, and more than 60% develop PHEOs. Generally, the MTC in patients with MEN2B is more aggressive clinically compared to the MTC in patients with MEN2A.

MTC is derived from the thyroid C-cells, which secrete the peptide calcitonin (CTN), and the glycoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). Measurement of serum CTN levels is especially useful in the timing of thyroidectomy in patients who have inherited a mutated RET allele, and in the evaluation of patients following thyroidectomy. The calculation of the time it takes for serum levels of CTN to double provides a reliable index of the rate of tumor growth, and thereby patient prognosis.

The Molecular Basis of the MEN2 syndromes

The MEN2 variants, and MEN2B are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, and each is caused by germline mutations in the RET (REarranged during Transfection) protooncogene.(Donis-Keller, et al. 1993; Mulligan, et al. 1993) RET spans 21 exons on chromosome 10 (10q11.2) and encodes a highly conserved single pass transmembrane receptor of the tyrosine kinase family. The gene is expressed in cells derived from the neural crest: the brain, parasympathetic and sympathetic ganglia, the thyroid C-cells, the adrenal medulla, and the urogenital tract.(Nakamura, et al. 1994)

Characterization of MEN2A

Classical MEN2A is the most common MEN2A variant, and 95% of patients have RET mutations in codons 609, 611, 618, or 620 of exon 10, or codon 634 of exon 11. In patients with RET mutations in codon C634, the MTC has an earlier age of onset, and a more aggressive clinical course, compared to that in patients with RET mutations in codons other than C634. If an MTC is more aggressive than that expected with a specific RET codon mutation, it is important to completely sequence the tumor DNA, since a second RET codon mutation may be the reason for the MTC’s unexpected behavior.(Cerutti and Maciel 2013)

In patients with RET C634 codon mutations, the incidence of PHEO is 50% by the 5th decade and approaches 90% by the 8th decade.(Imai, et al. 2013) In patients with RET codon mutations, other than C634, the incidence of PHEOs ranges from 4% to 25%. (Table 1) Prior to the advent of genetic screening in families with MEN2A, the most common cause of death was PHEOs not MTC.(Lips, et al. 1995) HPTH occurs in about 30% of patients with MEN2A and RET 634 codon mutations, and is less frequent in patients with mutations in other RET codons. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Relationship of Common RET Mutations to Risk of Aggressive MTC in MEN2A and MEN2B, and to the Incidence of PHEO, HPTH, CLA and HD in MEN2A.

| RET Mutation | Exon | MTC risk levela | Incidence of PHEOb | Incidence of HPTHb | CLAc | HDc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G533C | 8 | MOD | + | − | N | N |

| C609F/G/R/S/Y | 10 | MOD | +/++ | + | N | Y |

| C611F/G/S/Y/W | 10 | MOD | +/++ | + | N | Y |

| C618F/R/S | 10 | MOD | +/++ | + | N | Y |

| CF20F/R/S | 10 | MOD | +/++ | + | N | Y |

| C630R/Y | 11 | MOD | +/++ | + | N | N |

| D631Y | 11 | MOD | +++ | − | N | N |

| C634F/G/R/S/W/Y | 11 | H | +++ | ++ | Y | N |

| K666E | 11 | MOD | + | − | N | N |

| E768D | 13 | MOD | − | − | N | N |

| L790F | 13 | MOD | + | − | N | N |

| V804L | 14 | MOD | + | + | N | N |

| V804M | 14 | MOD | + | + | Y | N |

| A883F | 15 | H | +++ | − | N | N |

| S891A | 15 | MOD | + | + | N | N |

| R912P | 16 | MOD | − | − | N | N |

| M918T | 16 | HST | +++ | − | N | N |

Risk of aggressive MTC: MOD=Moderate, H=High, HST=Highest

MTC=medullary thyroid carcinoma, PHEO=pheochromocytoma, HPTH=hyperparathyroidism

CLA=cutaneous lichen amyloidosis, HD=Hirschsprung’s Disease,

Incidence of PHEO and HPTH,

Y=positive occurrence, N=negative occurrence: +=~10%, ++=~0–30%, +++=~5-%.

From: The Revised American Thyroid Association Guidelines for the Management of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Thyroid, page 571, 2015. With permission from the American Thyroid Association and Mary Ann Liebert, Publisher

In MEN2A and CLA, the CLA is manifested by the presence of a skin lesion in the scapular region of the back, corresponding to dermatomes T2-T6. The CLA almost always occurs in patients with a RET 634 codon mutation, although there have been reports of CLA in patients with a RET V804 codon mutation, and a RET S891A codon mutation.(Gagel et al. 1989; Qi, et al. 2015; Rothberg, et al. 2009; Scapineli, et al. 2016) Originally CLA was thought to be uncommon, but it has been reported to occur in 35% of patients with a RET 634 codon mutation.(Verga, et al. 2003) Patients may be asymptomatic, but most of them complain of localized pruritus, and persistent scratching that results in thickened hyperpigmented skin. In youngsters, the CLA may precede clinical evidence of MEN2A, and thereby serve as a marker for the presence of a mutated RET allele, and the impending development of MTC.

HD occurs in approximately 7% of patients with MEN2A; conversely 2–5% of patients with HD have MEN2A.(Decker and Peacock 1998; Sijmons et al. 1998) In MEN2A and HD, the HD occurs in patients with RET codon mutations in exon 10: 609 (15%), 611 (5%), 618 (30%) and 620 (50%).(Borst, et al. 1995; Mulligan, et al. 1994) RET mutations also occur in approximately 50% of patients with hereditary HD, and in 20% to 33% of patients with sporadic HD.(Amiel et al. 2008; Romeo, et al. 1994) The RET mutations in HD are “loss of function” mutations that disable RET activation, whereas the RET mutations in MEN2A are “gain of function” mutations that induce constitutive activation of RET. It seems paradoxical that HD should develop in patients with MEN2A; the explanation being that the RET mutations in exon 10 are sufficient to trigger neoplastic transformation of the thyroid C-cells and the adrenal chromaffin cells, but are insufficient to express the RET protein at the cell surface, resulting in a failed trophic response in precursor neurons.(Asai, et al. 2006) It is important to screen for MEN2A in patients with HD, and to screen for HD in patients with MEN2A, and exon 10 mutations.

Familial Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma, initially thought to be a stand-alone entity, different from MEN2A and MEN2B, is now considered a variant of MEN2A. Many families classified as FMTC variants, move forthwith into the Classic MEN2A category if a single-family member develops a PHEO or HPTH.(Oliveira, et al. 2011)

MEN2B

MEN2B accounts for 5% of hereditary MTCs and is characterized by the presence of MTC, PHEOs, ganglioneuromatosis of the aerodigestive tract, and a typical phenotype, consisting of a marfanoid habitus, typical facies, and skeletal abnormalities. Over 75% of cases of MEN2B are sporadic, the result of de novo RET mutations in a normal appearing parent-almost always the father.(Carlson, et al. 1994) The mean age at diagnosis is 14.2 years and despite the typical phenotype, patients often go unrecognized until the MTC has spread beyond the thyroid gland and is incurable. In families with hereditary MEN2B the disease may be apparent at, or soon after birth, when thyroidectomy may be curative; however, the MTC is aggressive in this setting, and rare infants have regional lymph node metastases at the time of thyroidectomy.(Zenaty, et al. 2009) Approximately 95% of patients with MEN2B have a RET M918T codon mutation, and the remainder have a RET A833F codon mutation.(Eng, et al. 1994; Gimm, et al. 1997) The MTC appears to be less aggressive in patients with the RET A833F codon mutation compared to the MTC in patients with a RET M918T codon mutation.(Jasim, et al. 2011)

Over 100 RET point mutations, duplications, insertions, deletions, or fusions have been identified in patients with MEN2A, whereas only two RET mutations have been identified in patients with MEN2B.(Wells et al. 2015) The most common RET mutations occurring in patients with MEN2A and MEN2B, the associated aggressiveness of the MTC, and the frequency of the MEN2 variants, PHEOs and HPTH are shown in Table 1.

Although RET mutations appear to be the sole driver in patients with the MEN2 syndromes, there are RET variants of unknown significance (VUS) that are neither benign polymorphisms or active pathogenic mutations. Family members with the same VUS should be followed expectantly.(Crockett, et al. 2011)

Sporadic MTC

In 75% of patients with MTC the disease is sporadic arising from somatic de novo RET mutations. Approximately 40% of patients have RET M918T codon mutations, and approximately 30% have RAS mutations, most often KRAS or HRAS.(Moura, et al. 2015; Moura, et al. 2011) In patients with sporadic MTC, a RET M918T codon mutation is associated with a more aggressive clinical course, compared to that in patients with RAS mutations.(Elisei, et al. 2008) Genetic screening is important in patients with presumed sporadic MTC, since 7% to 15% of them will be found to have a RET germline mutation and hereditary MTC.(Eng, et al. 1995; Kihara, et al. 2016; Romei, et al. 2011)

Management of MTC

In families with MEN2A, it is critical to establish a genetic screening program to identify members who have inherited a mutated RET allele and offer them genetic counselling. In most kindreds with MEN2A, family members decide to have a thyroidectomy if they are found to have a mutated RET allele, or clinical evidence of MTC. Some elderly patients who have a RET mutation do not wish to have a thyroidectomy, even if they have a thyroid nodule. Most adult members of families with MEN2A advise a thyroidectomy in their children, since it is the only cure for MTC, assuming that the tumor has not developed, or is confined to the thyroid gland. Even though the procedure is usually referred to as a prophylactic thyroidectomy, and indeed a few patients have no evidence of a C-cell disorder in the thyroidectomy specimen, the majority of patients have C-cell hyperplasia, or small foci of MTC. Therefore, a better term for the procedure is early thyroidectomy.

Before the discovery of RET mutations in patients with MEN2A, the detection of an elevated serum calcitonin level served as the basis for timing thyroidectomy. Although, this strategy was useful, the frequency of false positive values led to unnecessary operations.(Marsh, et al. 1996) Following the discovery of RET mutations as the cause of MEN2, oncologists based the timing of thyroidectomy largely on the presence of a specific RET codon mutation. There were also problems with this strategy, since there is substantial variability in the age at which MTC develops, not only among different families with the same RET codon mutation; but among individuals within the same family. Currently, the generally accepted practice is to use a combination of genetic testing and the basal or stimulated serum calcitonin level to decide the timing of thyroidectomy.

Generally, in patients with MEN2A, and a RET C634 codon mutation the thyroid should be removed around 5 years of age. The surgeon can avoid dissecting the central zone of the neck, since lymph node metastases rarely occur by this age. When there is no central zone dissection, the parathyroid glands can be left in situ if they are normal in size, realizing that the patient may develop HPTH later in life. In the unusual situation where the parathyroid glands are enlarged, they can be managed by radical subtotal 31/2 gland resection or total parathyroidectomy with heterotopic autotransplantation. Whatever the mode of management, it is important to preserve parathyroid function, since without it the patient is committed to life-long dependency on calcium and vitamin D replacement therapy, and is also vulnerable to the potential complications associated with chronic hypocalcemia.

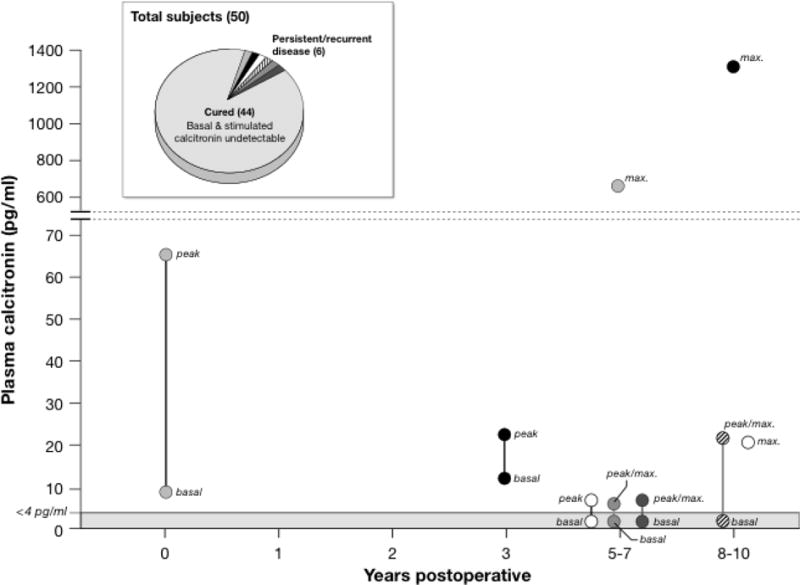

Measurement of the serum calcitonin level, in the basal state or following stimulation with pentagastrin, or calcium, or both, is the most reliable way to detect persistent or residual MTC after thyyroidectomy.(Skinner, et al. 2005) Some investigators consider that a basal serum calcitonin level within the normal range, or a pentagastrin stimulated serum calcitonin less than 10 pg/ml following thyroidectomy represents a “biochemical cure”.(Barbot, et al. 1994; Franc, et al. 2001) A detectable basal postoperative serum CTN, even within the normal range, represents an incurable state, although the progression of the MTC is variable, and patients may go for years before they develop a clinical recurrence, if they ever do. In one study, 50 consecutive youngsters with a germline RET mutation were evaluated at least 5 years after prophylactic thyroidectomy.(Skinner et al. 2005) The basal and stimulated (with the combined intravenous infusion of pentagastrin and calcium) serum calcitonin levels were undetectable in 44 (88%) patients, but were elevated in 2 patients, one immediately postoperatively, and the other at 3 years postoperatively. In 4 patients, the basal serum calcitonin levels were undetectable at every evaluation time point, but the stimulated calcitonin levels were above the normal range from 4 to 10 years after thyroidectomy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The results of 50 consecutive patients, (mean age 10 years; range 3-19 years) who had inherited a mutated RET allel and were treated by prophylactic thyroidectomy. All patients were evaluated 5 to 10 years after surgery (mean 7 years) by physical examination, and measurement of serum calcitonin levels following the combined administration of calcium and pentagastrin. Basal and stimulated serum calcitonin levels were undetectable in 44 patients, and they were considered cured. Basal serum calcitonin levels were undetectable in 4 patients but they increased above the normal range following stimulation 4 to 9 years after thyroidectomy. In two patients basal and stimulated serum calcitonin levels were above the normal range, one immediately after thyroidectomy, and the other not until 3 years after thyroidecomy.

From: Skinner MA, et.al., Prophylactic Thyroidectomy in Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2A. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2005; 353:10005-13. Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.

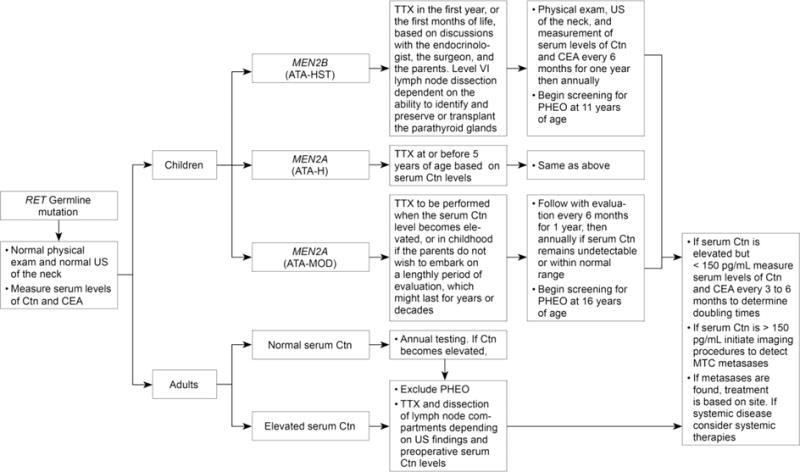

Prophylactic thyroidectomy, although extremely useful in youngsters, applies to a small number of patients with hereditary MTC, and no patients with sporadic MTC. In newly discovered families with MEN2A, one finds all stages of disease. In 75% of patients with clinically evident thyroid nodules the MTC has already spread to regional lymph nodes, and 10% of patients have metastases at distant sites.(Moley 2010; Weber, et al. 2001) In some patients, even the elderly, the MTC is occult, the only evidence of its presence being an elevated serum calcitonin level. The management algorithm for patients found to have a RET germline mutation is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Management of patients with a RET germline mutation detected on genetic screening. ATA, American Thyroid Association risk categories for aggressive medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) (HST, highest risk, H, high risk, MOD, moderate risk); Ctn, calcitonin; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; HPTH, hyperparathyroidism; PHEO, pheochromocytoma;RET, REarranged during Transfection; TTX, total thyroidectomy; US, ultrasound:

From: Wells SA, et.al., Revised American Thyroid Association Guidelines for the Management of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Thyroid, 2015; 15: page 584. With permission from the American Thyroid Association and Mary Ann Liebert, Publisher

The preferred operation for most patients is total thyroidectomy with dissection of lymph nodes in the central neck. Additional lymph node compartments are dissected if there is evidence of metastases on preoperative imaging studies, or at the time of thyroidectomy. Life-long follow-up is indicated, beginning every three months postoperatively, and at longer intervals if there is no evidence of persistent or recurrent disease in the first year after thyroidectomy. Serial measurements of serum calcitonin and CEA levels are useful in documenting disease progression, and especially in the calculation of the time that it takes for the two markers to double. In a recent study of 65 patients, the 10-year survival was 8% in patients whose serum CTN doubling time was less than 6 months, 37% in patients with doubling times between 6 and 24 months, and 96% in patients with doubling times greater than 24 months.(Barbet, et al. 2005) When the doubling times of serum CEA and serum calcitonin are concordant, the predictability of disease progression and prognosis is more accurate.(Laure Giraudet, et al. 2008)

Management of PHEO

Half or more of the patients with MEN2A and MEN2B develop PHEOs, the incidence increasing with age. The diagnosis of a PHEO succeeds the diagnosis of MTC in ~50% of patients, is coterminous with the diagnosis of MTC in ~40% of patients, and precedes the diagnosis of MTC in ~10% of patients.(Rodriguez, et al. 2008) The PHEOs are almost always benign, multicentric, and confined to the adrenal gland.(Modigliani, et al. 1995) Regardless of whether the patient has MEN2A or MEN2B, it is critical to exclude the presence of a PHEO prior to any diagnostic or therapeutic intervention. Following resection of one or more PHEOs, prolonged evaluation is important for two reasons. In the majority of patients, a contralateral PHEO will develop within 10 years after a unilateral adrenalectomy.(Asari, et al. 2006; Lairmore, et al. 1993) Following a bilateral adrenalectomy, patients are at risk for an Addisonian crisis, especially if they become injured, or ill, or receive inadequate glucocorticoid replacement.(Lairmore et al. 1993) Recognizing the complications associated with bilateral adrenalectomies, surgeons have recently turned to performing subtotal adrenalectomies in an attempt to preserve sufficient adrenal cortical tissue and obviate the need for glucocorticoid replacement, even under stressful conditions. Thus far, the experience has been mixed, as about half of the patients require supplemental glucocorticoids, and from 3% to 20% of patients develop a recurrent PHEO at some time after surgery.(Brauckhoff and Dralle 2012; Brauckhoff, et al. 2008; Scholten, et al. 2011) Cortical sparing adrenalectomy seems promising; however, long term evaluation of many patients is necessary before the worth of the technique is established.

Management of HPTH

Hyperparathyroidism occurs in approximately 30% of patients with MEN2A, most often in patients with RET mutations in exon 10 and exon 11, especially RET codon C634. The mean age at diagnosis is 33.7 years. The HPTH is usually mild and asymptomatic, but surgical resection is indicated if patients develop symptoms or signs related to hypercalcemic. The surgical options are either, subtotal 31/2 gland resection, or total parathyroidectomy with a parathyroid autograft to a heterotopic site. The size of the individual parathyroid glands may vary, and the surgeon may be tempted to remove only those that are enlarged; however, this approach carries the risk that patients will develop persistent or recurrent HPTH. It is important that the surgeon identify and mark the sites of parathyroid glands left in situ, in order to identify them if the patient develops HPTH and requires reoperative surgery. The. development of HPTH in patients who have had a prior thyroidectomy presents a challenge for the surgeon. Localization procedures, such as ultrasound, CT scans, and sestamibi scans, are useful to identify parathyroid glands prior to repeat exploration of the neck.

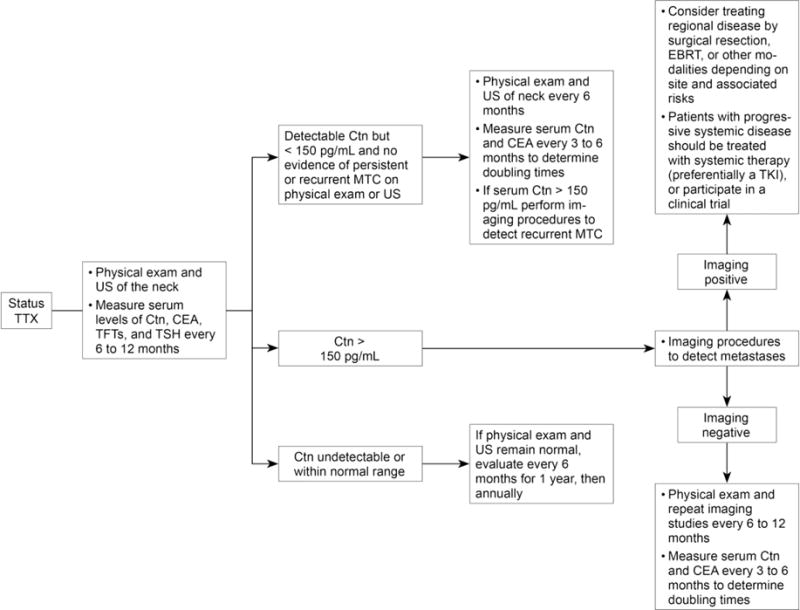

Management of Patients with Persistent or Recurrent MTC

Patients who have a total thyroidectomy for MTC are evaluated at varying intervals by physical examination and laboratory tests, including measurement of serum levels of CTN and CEA. Imaging studies are indicated if the serum CTN level exceeds 150 pg/ml, or if there is clinical evidence of recurrent MTC. Repeat operations in patients with regional node metastases are rarely curative, and the treatment of patients with distant metastases is palliative.(Pelizzo, et al. 2007; Scollo, et al. 2003; Wells et al. 2015) In patients whose advanced MTC is not amenable to surgery the treatment options are chemotherapy, a molecular targeted therapeutic (MTT), or continued observation. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Management of patients following thyroidectomy for persistent or recurrent medullary thyroid carcinoma. Ctn, calcitonin; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; EBRT, external beam radiotherapy; MTC, medullary thyroid carcinoma; TFTs, thyroid function tests; TSH, thyrotropin; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; TTX, total thyroidectomy; US, ultrasound.

From: Wells SA, et.al., Revised American Thyroid Association Guidelines for the Management of Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Thyroid, 2015; 15: page 589. With permission from the American Thyroid Association and Mary Ann Liebert, Publisher.

Chemotherapy

Formerly, either single agent or combination chemotherapy, was front-line therapy for patients with advanced MTC; however, with most regimens, responses were infrequent and of short duration. Doxorubicin was the first chemotherapeutic that the FDA approved for the treatment of patients with advanced thyroid cancer, but it is seldom given alone, and is more often combined with either vindesine or cisplatin.(Gottlieb, et al. 1972; Husain, et al. 1978; Scherubl, et al. 1990) The combined regimen of dacabarzine, vincristine, and cyclophosphamide is moderately efficacy in patients with advanced MTC, and is currently the chemotherapeutic regimen of choice for patients with advanced MTC who have failed to respond to, or become resistant to, MTTs.(Deutschbein, et al. 2011; Tuttle, et al. 2014; Wu, et al. 1994)

External beam radiation (EBRT)

EBRT as adjuvant therapy is not indicated in patients with primary MTC, and is of little benefit in the treatment of patients with regional metastases, unless there is impending invasion of vital structures. EBRT is often palliative in patients with metastases to distant sites, such as brain or bone.

Molecular targeted therapeutics

In the normal state, external growth factors or ligands, bind to cell surface receptor tyrosine kinases, and transmit a series of intracellular signals. Mutations in these receptors lead to a state of constitutive activation with continuous signaling to the nucleus and immortalization of the cell. Recognizing that the mutated receptors are vulnerable targets, clinical investigators in collaboration with the pharmaceutical industry began to develop specific MTTs for patients with advanced malignancies. The first MTT to show efficacy in patients with a malignant disease (chronic myelogenous leukemia [CML]) was the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), gleevec (imatinib).(Druker, et al. 2001) In a clinical trial of imatinib in patients with CML, there was, at 10.9 years, an overall survival of 83.3% and a complete cytogenetic remission of 82.8%.(Hochhaus, et al. 2017) The efficacy of imatinib in trials of patients with CML created great excitement among oncologists. Unfortunately, the experience with gleevec has not been replicated with various MTTs in patients with solid organ malignancies; however, in patients with advanced MTC there have been encouraging results in clinical studies of 2 MTTs.

The first TKI approved by the FDA for any thyroid cancer was ZD6474, or vandetanib, an orally available anilinoquinazoline that in preclinical studies blocked the enzymatic activity of RET-derived oncoproteins at a one-half maximal inhibitory concentration of 100 nM. Also in nude mice, ZD6474 blocked the formation of tumors derived from NIH-RET/PTC3 cells.(Carlomagno, et al. 2002) In a phase II trial of vandetanib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic MTC the drug administered in a maximum tolerated dose of 300 mg/day induced partial remissions in 6 of 30 patients, and disease stabilization in 22 patients. The estimated progression free survival (PFS) was 27.9 months.(Wells, et al. 2010) Another trial of patients treated with vandetanib, 100 mg/day, gave similar results.(Robinson, et al. 2010) Supported by the results of the phase II trials, investigators initiated a prospective, double blind, randomized, phase III trial, evaluating the efficacy of vandetanib, compared to placebo in patients with advanced MTC.(Wells, et al. 2012) There was an estimated median PFS of 30.5 months in patients treated with vandetanib, compared to 19.3 months in patients receiving placebo (Table 2). Because of grade III adverse events, primarily diarrhea, rash, hypertension, and headache, 35% of patients required dose-reductions. Based on results of the phase III trial the FDA approved vandetanib for the treatment of patients with progressive, advanced metastatic MTC.(Wells et al. 2012)

Table 2.

Clinical Trials with Molecular Targeted Therapeutics in Patients With Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma

| Drug (ref) | Study | No. Pts. | PR (%) | SD (%) | PFS (mos.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axitinib77 | Phase II | 11 | 18 | 27* | NA |

| Motesanib78 | Phase II | 91 | 2 | 48** | 12 |

| Sorafenib74 | Phase II | 16 | 6.3 | 87.5* | 17.9 |

| Sunitinib79 | Phase II | 6 | 50 | NA | NA |

| Vandetanib69 | Phase II | 30 | 20 | 53** | 27.9# |

| Vandetanib70 (100 mg/d) | Phase II | 19 | 16 | 53** | NA |

| Cabozantinib73 | Phase II | 37 | 29 | 41** | NA |

| Vandetanib71 | Phase III | 231/100 | HR 0.46 | 0.46 (ORR) | 30.5# |

| Cabozantinib76 | Phase III | 219/111 | HR 0.28 | 0.28 (ORR) | 11.2# |

| Imatinib80 | Phase II | 15 | 0 | 27** | 0 |

| Imatinib81 | Phase II | 9 | 0 | 56* | 0 |

| Sorafenib plus Tipifarnib82 | Phase II | 13 | 38 | 31** | 17 |

No. Pts.= Number of Patients, PR = Partial Response (RECIST), SD = Stable Disease, mos. = months, PFS = Progression Free Survival,

= > 4mos,

= > 6 mos.,

= Estimated PFS in months,

NA = Not Available, HR = hazard ratio comparing PFS in treated compared to placebo control patients, ORR = Overall response rate, Ref = reference.

From: Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2 and Familial Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma: An Update. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, page 3159, 2013. With permission from the Endocrine Society.

XL184, or cabozantinib, an orally available TKI with activity against MET, VEGFR2, and RET, prevented phosphorylation of target kinases, reduced cell growth, and inhibited angiogenesis and tumor invasiveness in several cell lines.(Yakes, et al. 2011) In a phase I/II trial of cabozantinib in patients with advanced MTC, 29% had a partial remission and 68% had stable disease.(Kurzrock, et al. 2011) In a subsequent phase III prospective, double blind, randomized trial of cabozantinib compared to placebo in patients with advanced MTC. The PFS in patients receiving cabozantinib was longer than that in patients receiving placebo (11.2 months compared to 4 months (Table 2). Grade 3 or 4 adverse events, including hemorrhage, fistulas, and gastrointestinal perforation occurred in 69% of patients treated with cabozantinib, and there were 9 deaths related to cabozantinib treatment. Based on the results of the phase III clinical trial, the FDA approved cabozantinib for the treatment of patients with advanced MTC.(Elisei, et al. 2013)

Other MTTs have shown efficacy in patients with advanced MTC, but none has been evaluated in phase III clinical trials (Table 2). Some of the compounds are used as second line therapy in patients who fail treatment with either vandetanib or cabozantinib. The agent most often used is sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor, which has shown efficacy in phase I and phase II clinical trials of patients with MTC. The most common response has been disease stabilization.(Capdevila, et al. 2012; Lam, et al. 2010)

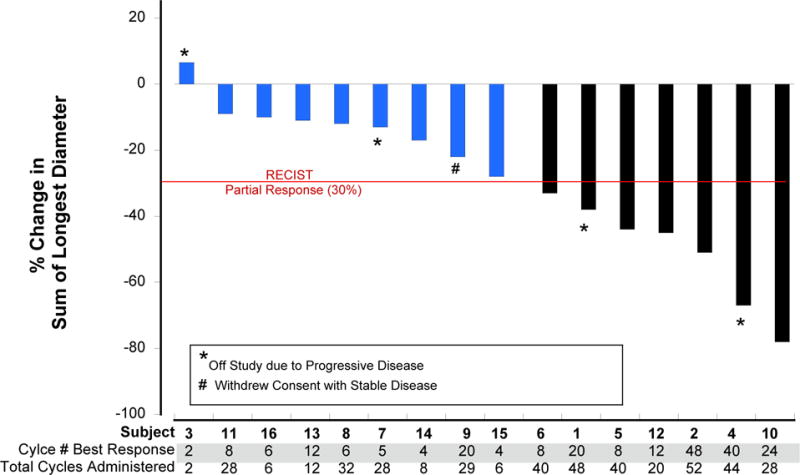

The experience with MTTs in the treatment of patients with advanced MTC has been sobering. While vandetanib and cabozantinib have improved progression free survival, there has been no improvement in overall survival. Moreover, virtually all responses have been partial, not complete, and almost all patients become resistant to the therapy and develop progressive disease. For unknown reasons, the response to therapy can vary markedly, as noted in Figure 4, which shows results of vandetanib treatment in 16 children with advanced MTC. Except for one child with sporadic MTC, all children had MEN2B and the M918T RET mutation, all received the same drug, and all of them looked alike; yet their responses to vandetanib varied from a ~10% to an ~80 reduction in tumor size. One would expect a similar response rate among the children in the study, yet the responses of the patients was no different from that seen in a more disparate patient population of adults with sporadic MTC, who were treated with vandetanib.(Robinson et al. 2010; Wells et al. 2012) Thus, the response to a given MTT is multifactorial, and depends not only on the specific target mutation, and the treatment drug, but on unknown factors in the host. Considering the varied responses, and the associated toxicities to the current MTTs used to treat patients with MTC, the pharmaceutical industry is concentrating on the development of MTTs that have minimal toxicity and a greater specificity for inhibiting mutated RET. Two such drugs, (BLU-667 [NCT03037385]; Blueprint Medicines, Inc., Cambridge, MA) and (LOXO-292 [NCT03157128]; Loxo Oncology, Stamford Conn), are currently being evaluated in phase II clinical trials. The goal is to cure patients with advanced MTC, or at least convert their progressive disease to one that is chronic and long lasting.

Figure 4.

A waterfall plot showing reduction in size of metastatic MTC in children with MEN2B who received vanetanib.

From: Fox E. et.al., Vandetanib in Children and Adolescents with Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2B Associated Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research, 2013; 19:4239-48; Figure 3. With permission from the American Association for Cancer Reseach.

Acknowledgments

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- Amiel J, Sproat-Emison E, Garcia-Barcelo M, Lantieri F, Burzynski G, Borrego S, Pelet A, Arnold S, Miao X, Griseri P, et al. Hirschsprung disease, associated syndromes and genetics: a review. J Med Genet. 2008;45:1–14. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.053959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai N, Jijiwa M, Enomoto A, Kawai K, Maeda K, Ichiahara M, Murakumo Y, Takahashi M. RET receptor signaling: dysfunction in thyroid cancer and Hirschsprung’s disease. Pathol Int. 2006;56:164–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.01942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asari R, Scheuba C, Kaczirek K, Niederle B. Estimated risk of pheochromocytoma recurrence after adrenal-sparing surgery in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1199–1205. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.12.1199. discussion 1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbet J, Campion L, Kraeber-Bodere F, Chatal JF, Group GTES Prognostic impact of serum calcitonin and carcinoembryonic antigen doubling-times in patients with medullary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:6077–6084. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbot N, Calmettes C, Schuffenecker I, Saint-Andre JP, Franc B, Rohmer V, Jallet P, Bigorgne JC. Pentagastrin stimulation test and early diagnosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma using an immunoradiometric assay of calcitonin: comparison with genetic screening in hereditary medullary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78:114–120. doi: 10.1210/jcem.78.1.7904611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst MJ, VanCamp JM, Peacock ML, Decker RA. Mutational analysis of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A associated with Hirschsprung’s disease. Surgery. 1995;117:386–391. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauckhoff M, Dralle H. Function-preserving adrenalectomy for adrenal tumors. Chirurg. 2012;83:519–527. doi: 10.1007/s00104-011-2192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauckhoff M, Stock K, Stock S, Lorenz K, Sekulla C, Brauckhoff K, Thanh PN, Gimm O, Spielmann RP, Dralle H. Limitations of intraoperative adrenal remnant volume measurement in patients undergoing subtotal adrenalectomy. World J Surg. 2008;32:863–872. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9402-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila J, Iglesias L, Halperin I, Segura A, Martinez-Trufero J, Vaz MA, Corral J, Obiols G, Grande E, Grau JJ, et al. Sorafenib in metastatic thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19:209–216. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlomagno F, Vitagliano D, Guida T, Ciardiello F, Tortora G, Vecchio G, Ryan AJ, Fontanini G, Fusco A, Santoro M. ZD6474, an orally available inhibitor of KDR tyrosine kinase activity, efficiently blocks oncogenic RET kinases. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7284–7290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson KM, Bracamontes J, Jackson CE, Clark R, Lacroix A, Wells SA, Jr, Goodfellow PJ. Parent-of-origin effects in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55:1076–1082. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti JM, Maciel RM. An unusual genotype-phenotype correlation in MEN 2 patients: should screening for RET double germline mutations be performed to avoid misleading diagnosis and treatment? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;79:591–592. doi: 10.1111/cen.12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett DK, Piccolo SR, Ridge PG, Margraf RL, Lyon E, Williams MS, Mitchell JA. Predicting phenotypic severity of uncertain gene variants in the RET proto-oncogene. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker RA, Peacock ML. Occurrence of MEN 2a in familial Hirschsprung’s disease: a new indication for genetic testing of the RET proto-oncogene. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90433-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutschbein T, Matuszczyk A, Moeller LC, Unger N, Yuece A, Lahner H, Mann K, Petersenn S. Treatment of advanced medullary thyroid carcinoma with a combination of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine: a single-center experience. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2011;119:540–543. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1279704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donis-Keller H, Dou S, Chi D, Carlson KM, Toshima K, Lairmore TC, Howe JR, Moley JF, Goodfellow P, Wells SA., Jr Mutations in the RET proto-oncogene are associated with MEN 2A and FMTC. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:851–856. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.7.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, Peng B, Buchdunger E, Ford JM, Lydon NB, Kantarjian H, Capdeville R, Ohno-Jones S, et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1031–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elisei R, Cosci B, Romei C, Bottici V, Renzini G, Molinaro E, Agate L, Vivaldi A, Faviana P, Basolo F, et al. Prognostic significance of somatic RET oncogene mutations in sporadic medullary thyroid cancer: a 10-year follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:682–687. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elisei R, Schlumberger MJ, Muller SP, Schoffski P, Brose MS, Shah MH, Licitra L, Jarzab B, Medvedev V, Kreissl MC, et al. Cabozantinib in progressive medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3639–3646. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng C, Mulligan LM, Smith DP, Healey CS, Frilling A, Raue F, Neumann HP, Ponder MA, Ponder BA. Low frequency of germline mutations in the RET proto-oncogene in patients with apparently sporadic medullary thyroid carcinoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1995;43:123–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb01903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng C, Smith DP, Mulligan LM, Nagai MA, Healey CS, Ponder MA, Gardner E, Scheumann GF, Jackson CE, Tunnacliffe A, et al. Point mutation within the tyrosine kinase domain of the RET proto-oncogene in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B and related sporadic tumours. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:237–241. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farndon JR, Leight GS, Dilley WG, Baylin SB, Smallridge RC, Harrison TS, Wells SA., Jr Familial medullary thyroid carcinoma without associated endocrinopathies: a distinct clinical entity. Br J Surg. 1986;73:278–281. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800730411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franc S, Niccoli-Sire P, Cohen R, Bardet S, Maes B, Murat A, Krivitzky A, Modigliani E, French Medullary Study G Complete surgical lymph node resection does not prevent authentic recurrences of medullary thyroid carcinoma. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;55:403–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagel RF, Levy ML, Donovan DT, Alford BR, Wheeler T, Tschen JA. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2a associated with cutaneous lichen amyloidosis. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:802–806. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-10-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimm O, Marsh DJ, Andrew SD, Frilling A, Dahia PL, Mulligan LM, Zajac JD, Robinson BG, Eng C. Germline dinucleotide mutation in codon 883 of the RET proto-oncogene in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B without codon 918 mutation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:3902–3904. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.11.4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb JA, Hill CS, Jr, Ibanez ML, Clark RL. Chemotherapy of thyroid cancer. An evaluation of experience with 37 patients. Cancer. 1972;30:848–853. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197209)30:3<848::aid-cncr2820300336>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazard JB, Hawk WA, Crile G., Jr Medullary (solid) carcinoma of the thyroid; a clinicopathologic entity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1959;19:152–161. doi: 10.1210/jcem-19-1-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochhaus A, Larson RA, Guilhot F, Radich JP, Branford S, Hughes TP, Baccarani M, Deininger MW, Cervantes F, Fujihara S, et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Imatinib Treatment for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:917–927. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JMS, John H, Dougald C, MacGillivray, Ross Howard, Malchoff Carl D, Malchoff Diana M. The Sipple Syndrome: From Clinical Description Genetic Analysis in the Index Family. Endocrinologist. 1996;6:427–430. [Google Scholar]

- Husain M, Alsever RN, Lock JP, George WF, Katz FH. Failure of medullary carcinoma of the thyroid to respond to doxorubicin therapy. Horm Res. 1978;9:22–25. doi: 10.1159/000178893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T, Uchino S, Okamoto T, Suzuki S, Kosugi S, Kikumori T, Sakurai A, Japan MENCo High penetrance of pheochromocytoma in multiple endocrine neoplasia 2 caused by germ line RET codon 634 mutation in Japanese patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;168:683–687. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasim S, Ying AK, Waguespack SG, Rich TA, Grubbs EG, Jimenez C, Hu MI, Cote G, Habra MA. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B with a RET proto-oncogene A883F mutation displays a more indolent form of medullary thyroid carcinoma compared with a RET M918T mutation. Thyroid. 2011;21:189–192. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara M, Miyauchi A, Yoshioka K, Oda H, Nakayama A, Sasai H, Yabuta T, Masuoka H, Higashiyama T, Fukushima M, et al. Germline RET mutation carriers in Japanese patients with apparently sporadic medullary thyroid carcinoma: A single institution experience. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2016;43:551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2015.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzrock R, Sherman SI, Ball DW, Forastiere AA, Cohen RB, Mehra R, Pfister DG, Cohen EE, Janisch L, Nauling F, et al. Activity of XL184 (Cabozantinib), an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2660–2666. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lairmore TC, Ball DW, Baylin SB, Wells SA., Jr Management of pheochromocytomas in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 syndromes. Ann Surg. 1993;217:595–601. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199306000-00001. discussion 601-593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam ET, Ringel MD, Kloos RT, Prior TW, Knopp MV, Liang J, Sammet S, Hall NC, Wakely PE, Jr, Vasko VV, et al. Phase II clinical trial of sorafenib in metastatic medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2323–2330. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laure Giraudet A, Al Ghulzan A, Auperin A, Leboulleux S, Chehboun A, Troalen F, Dromain C, Lumbroso J, Baudin E, Schlumberger M. Progression of medullary thyroid carcinoma: assessment with calcitonin and carcinoembryonic antigen doubling times. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:239–246. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lips CJ, Landsvater RM, Hoppener JW, Geerdink RA, Blijham GH, Jansen-Schillhorn van Veen JM, Feldberg MA, van Gils AP, Hoogenboom H, Berends MJ, et al. From medical history and biochemical tests to presymptomatic treatment in a large MEN 2A family. J Intern Med. 1995;238:347–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1995.tb01209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh DJ, McDowall D, Hyland VJ, Andrew SD, Schnitzler M, Gaskin EL, Nevell DF, Diamond T, Delbridge L, Clifton-Bligh P, et al. The identification of false positive responses to the pentagastrin stimulation test in RET mutation negative members of MEN 2A families. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1996;44:213–220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1996.505292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modigliani E, Vasen HM, Raue K, Dralle H, Frilling A, Gheri RG, Brandi ML, Limbert E, Niederle B, Forgas L, et al. Pheochromocytoma in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2: European study. The Euromen Study Group. J Intern Med. 1995;238:363–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1995.tb01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moley JF. Medullary thyroid carcinoma: management of lymph node metastases. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:549–556. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura MM, Cavaco BM, Leite V. RAS proto-oncogene in medullary thyroid carcinoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22:R235–252. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura MM, Cavaco BM, Pinto AE, Leite V. High prevalence of RAS mutations in RET-negative sporadic medullary thyroid carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E863–868. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan LM, Eng C, Attie T, Lyonnet S, Marsh DJ, Hyland VJ, Robinson BG, Frilling A, Verellen-Dumoulin C, Safar A, et al. Diverse phenotypes associated with exon 10 mutations of the RET proto-oncogene. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:2163–2167. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.12.2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan LM, Kwok JB, Healey CS, Elsdon MJ, Eng C, Gardner E, Love DR, Mole SE, Moore JK, Papi L, et al. Germ-line mutations of the RET proto-oncogene in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. Nature. 1993;363:458–460. doi: 10.1038/363458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Ishizaka Y, Nagao M, Hara M, Ishikawa T. Expression of the ret proto-oncogene product in human normal and neoplastic tissues of neural crest origin. J Pathol. 1994;172:255–260. doi: 10.1002/path.1711720305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann HP, Vortmeyer A, Schmidt D, Werner M, Erlic Z, Cascon A, Bausch B, Januszewicz A, Eng C. Evidence of MEN-2 in the original description of classic pheochromocytoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1311–1315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunziata V, Giannattasio R, Di Giovanni G, D’Armiento MR, Mancini M. Hereditary localized pruritus in affected members of a kindred with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A (Sipple’s syndrome) Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1989;30:57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1989.tb03727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira MN, Hemerly JP, Bastos AU, Tamanaha R, Latini FR, Camacho CP, Impellizzeri A, Maciel RM, Cerutti JM. The RET p.G533C mutation confers predisposition to multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A in a Brazilian kindred and is able to induce a malignant phenotype in vitro and in vivo. Thyroid. 2011;21:975–985. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelizzo MR, Boschin IM, Bernante P, Toniato A, Piotto A, Pagetta C, Nibale O, Rampin L, Muzzio PC, Rubello D. Natural history, diagnosis, treatment and outcome of medullary thyroid cancer: 37 years experience on 157 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:493–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi XP, Zhao JQ, Chen ZG, Cao JL, Du J, Liu NF, Li F, Sheng M, Fu E, Guo J, et al. RET mutation p.S891A in a Chinese family with familial medullary thyroid carcinoma and associated cutaneous amyloidosis binding OSMR variant p.G513D. Oncotarget. 2015;6:33993–34003. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BG, Paz-Ares L, Krebs A, Vasselli J, Haddad R. Vandetanib (100 mg) in patients with locally advanced or metastatic hereditary medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2664–2671. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez JM, Balsalobre M, Ponce JL, Rios A, Torregrosa NM, Tebar J, Parrilla P. Pheochromocytoma in MEN 2A syndrome. Study of 54 patients. World J Surg. 2008;32:2520–2526. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9734-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romei C, Cosci B, Renzini G, Bottici V, Molinaro E, Agate L, Passannanti P, Viola D, Biagini A, Basolo F, et al. RET genetic screening of sporadic medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) allows the preclinical diagnosis of unsuspected gene carriers and the identification of a relevant percentage of hidden familial MTC (FMTC) Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;74:241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo G, Ronchetto P, Luo Y, Barone V, Seri M, Ceccherini I, Pasini B, Bocciardi R, Lerone M, Kaariainen H, et al. Point mutations affecting the tyrosine kinase domain of the RET proto-oncogene in Hirschsprung’s disease. Nature. 1994;367:377–378. doi: 10.1038/367377a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg AE, Raymond VM, Gruber SB, Sisson J. Familial medullary thyroid carcinoma associated with cutaneous lichen amyloidosis. Thyroid. 2009;19:651–655. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scapineli JO, Ceolin L, Punales MK, Dora JM, Maia AL. MEN 2A-related cutaneous lichen amyloidosis: report of three kindred and systematic literature review of clinical, biochemical and molecular characteristics. Fam Cancer. 2016;15:625–633. doi: 10.1007/s10689-016-9892-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherubl H, Raue F, Ziegler R. Combination chemotherapy of advanced medullary and differentiated thyroid cancer. Phase II study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1990;116:21–23. doi: 10.1007/BF01612635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholten A, Valk GD, Ulfman D, Borel Rinkes IH, Vriens MR. Unilateral subtotal adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 patients: a feasible surgical strategy. Ann Surg. 2011;254:1022–1027. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318237480c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scollo C, Baudin E, Travagli JP, Caillou B, Bellon N, Leboulleux S, Schlumberger M. Rationale for central and bilateral lymph node dissection in sporadic and hereditary medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2070–2075. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijmons RH, Hofstra RM, Wijburg FA, Links TP, Zwierstra RP, Vermey A, Aronson DC, Tan-Sindhunata G, Brouwers-Smalbraak GJ, Maas SM, et al. Oncological implications of RET gene mutations in Hirschsprung’s disease. Gut. 1998;43:542–547. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.4.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipple J. The association of Pheochromocytoma and Thyroid Cancer. Am J Med. 1961;31:163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Sipple JH. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 syndromes: historical perspectives. Henry Ford Hosp Med J. 1984;32:219–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner MA, Moley JA, Dilley WG, Owzar K, Debenedetti MK, Wells SA., Jr Prophylactic thyroidectomy in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1105–1113. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner AL, Goodman AD, Powers SR. Study of a kindred with pheochromocytoma, medullary thyroid carcinoma, hyperparathyroidism and Cushing’s disease: multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 2. Medicine (Baltimore) 1968;47:371–409. doi: 10.1097/00005792-196809000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telenius-Berg M, Berg B, Hamberger B, Tibblin S, Tisell LE, Ysander L, Welander G. Impact of screening on prognosis in the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 syndromes: natural history and treatment results in 105 patients. Henry Ford Hosp Med J. 1984;32:225–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuttle RM, Haddad RI, Ball DW, Byrd D, Dickson P, Duh QY, Ehya H, Haymart M, Hoh C, Hunt JP, et al. Thyroid carcinoma, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:1671–1680. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0169. quiz 1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verga U, Fugazzola L, Cambiaghi S, Pritelli C, Alessi E, Cortelazzi D, Gangi E, Beck-Peccoz P. Frequent association between MEN 2A and cutaneous lichen amyloidosis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;59:156–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber T, Schilling T, Frank-Raue K, Colombo-Benkmann M, Hinz U, Ziegler R, Klar E. Impact of modified radical neck dissection on biochemical cure in medullary thyroid carcinomas. Surgery. 2001;130:1044–1049. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.118380a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells SA, Jr, Asa SL, Dralle H, Elisei R, Evans DB, Gagel RF, Lee N, Machens A, Moley JF, Pacini F, et al. Revised American Thyroid Association guidelines for the management of medullary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2015;25:567–610. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells SA, Jr, Gosnell JE, Gagel RF, Moley J, Pfister D, Sosa JA, Skinner M, Krebs A, Vasselli J, Schlumberger M. Vandetanib for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic hereditary medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:767–772. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells SA, Jr, Robinson BG, Gagel RF, Dralle H, Fagin JA, Santoro M, Baudin E, Elisei R, Jarzab B, Vasselli JR, et al. Vandetanib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic medullary thyroid cancer: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:134–141. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.5040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wermer P. Genetic aspects of adenomatosis of endocrine glands. Am J Med. 1954;16:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(54)90353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ED, Pollock DJ. Multiple mucosal neuromata with endocrine tumours: a syndrome allied to von Recklinghausen’s disease. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1966;91:71–80. doi: 10.1002/path.1700910109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Averbuch SD, Ball DW, de Bustros A, Baylin SB, McGuire WP., 3rd Treatment of advanced medullary thyroid carcinoma with a combination of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine. Cancer. 1994;73:432–436. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940115)73:2<432::aid-cncr2820730231>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakes FM, Chen J, Tan J, Yamaguchi K, Shi Y, Yu P, Qian F, Chu F, Bentzien F, Cancilla B, et al. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:2298–2308. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenaty D, Aigrain Y, Peuchmaur M, Philippe-Chomette P, Baumann C, Cornelis F, Hugot JP, Chevenne D, Barbu V, Guillausseau PJ, et al. Medullary thyroid carcinoma identified within the first year of life in children with hereditary multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A (codon 634) and 2B. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160:807–813. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]