Abstract

Background

An elevated Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is associated with worse outcomes in several malignancies. However, its role with contemporary immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) is unknown. We investigated the utility of NLR in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 ICB.

Methods

We examined NLR at baseline and 6 (±2) weeks later in 142 patients treated between 2009 and 2017 at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston, USA). Landmark analysis at 6 weeks was conducted to explore the prognostic value of relative NLR change on overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and objective response rate (ORR). Cox and logistic regression models allowed for adjustment of line of therapy, number of IMDC risk factors, histology and baseline NLR.

Results

Median follow up was 16.6 months (range: 0.7–67.8). Median duration on therapy was 5.1 months (<1–61.4). IMDC risk groups were: 18% favorable, 60% intermediate, 23% poor-risk. Forty-four percent were on first-line ICB and 56% on 2nd line or more. Median NLR was 3.9 (1.3–42.4) at baseline and 4.1 (1.1–96.4) at week 6. Patients with a higher baseline NLR showed a trend toward lower ORR, shorter PFS, and shorter OS. Higher NLR at 6 weeks was a significantly stronger predictor of all three outcomes than baseline NLR. Relative NLR change by ≥25% from baseline to 6 weeks after ICB therapy was associated with reduced ORR and an independent prognostic factor for PFS (p < 0.001) and OS (p = 0.004), whereas a decrease in NLR by ≥25% was associated with improved outcomes.

Conclusions

Early decline and NLR at 6 weeks are associated with significantly improved outcomes in mRCC patients treated with ICB. The prognostic value of the readily-available NLR warrants larger, prospective validation.

Keywords: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, PD-1/pd-L1 PD-L1, Immunotherapy, Renal cell carcinoma, Prognostic biomarker

Background

The treatment paradigm for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) has evolved over the last two decades from an era of cytokine regimens to VEGF targeted therapies (VEGF-TT) [1]. Prognostic models have also been refined over time, from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center criteria, which was initially established based on mRCC patients treated with interferon alfa (IFN-α) on clinical trials [2, 3], to the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) criteria, which has been validated in the era of oral VEGF-TT [4]. More recently, the treatment landscape has expanded to include contemporary immune checkpoint blockade (ICB). Nivolumab, a programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) antibody, became the first checkpoint inhibitor to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for second line mRCC in November 2015 [5, 6] and was subsequently approved for use in Europe [7]. Currently, there are several Phase 3 randomized trials investigating PD-1/PD-L1-based therapies in the first-line setting (NCT02420821, NCT02684006, NCT02811861). The first to result – the CheckMate-214 study – was stopped early due to a survival benefit seen with combination ICB versus single agent VEGF-TT [8]. Well-validated biomarkers that can be earlier prognostic or predictive readouts in mRCC treated with conventional ICB are lacking and represents an unmet need.

Inflammation is a recognized hallmark of cancer, however, the mechanism by which inflammation leads to worse outcomes in mRCC is not well described [9]. Neutrophilia is thought to occur as an inflammatory response and may lead to suppression of cytolytic activity of immune cells such as lymphocytes, natural killer cells, and activated T cells [10, 11]. An elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) has been shown to be associated with a poor prognosis in several solid tumors [12–14]. For example, in mRCC patients treated with VEGF-TT, an elevated NLR (NLR > 3) at baseline and an increase in NLR at 6-weeks were associated with worse outcomes in terms of survival and objective response rates [15]. The prognostic value of NLR in the current era of ICB has been evaluated in small subsets of patients, for example, with lung, melanoma, and bladder malignancies [16–18]. However, the utility of NLR in the context of contemporary immunotherapy for mRCC has not been well-defined. In this study, we investigated the association of baseline NLR, and changes during treatment, with outcomes in mRCC patients treated with conventional ICB.

Methods

Patients and data collection

We performed a retrospective analysis of all patients treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1-based treatment regimens at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) from 2009 to 2017. For patients who have received multiple ICB-based regimens, clinical information was only included from the earlier systemic treatment line. Data collected from patient’s electronic medical records included demographic information, smoking status, histology (including percent sarcomatoid and rhabdoid differentiation), International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) risk factors (hemoglobin < lower limit of normal, corrected calcium > upper limit of normal (ULN), platelets > ULN, absolute neutrophil count < ULN, Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) < 80%, and time from diagnosis to systemic treatment <1 year), lactate dehydrogenase level, Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte ratio (NLR) at start of IO and at 6 (±2) weeks after therapy initiation, drug target (PD-1, PD-L1), line of systemic therapy, duration of treatment, best response to PD-1/PD-L1, scan date of progression, date of death or last follow up. Response and progression was determined per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumor version 1.1 [19] by centralized review for patients treated on clinical trials or by an expert radiologist (KMK).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables, such as patient and disease characteristics, were described using frequencies and percentages. Quantitative variables were presented as medians and ranges. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare baseline NLR levels by patient and disease groups. We first investigated the impact of baseline NLR (as natural log-transformed [lnNLR]) on objective response rate (ORR: complete response or partial response), progression free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) using logistic or Cox regression models, adjusted for line of therapy, number of IMDC risk factors, and histology (clear cell RCC vs. non-clear cell RCC). PFS was defined as the time from the first dose of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 to radiographic or clinical progression or death, whichever came first, censored at last follow-up for patients who have not progressed. OS was calculated as the time from the first dose of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor to the date of death or last follow-up. Martingale residuals plots were used to verify the linear assumption of the Cox models for the continuous LnNLR values.

A landmark analysis at 6 weeks was conducted to explore the prognostic value of LnNLR at 6 (±2) weeks or relative NLR change (calculated as % change ({[NLR week 6 / NLR week 0] - 1}*100) and subsequently grouped in three groups (≥25% decrease, no change [<25% decrease to <25% increase], ≥25% increase) on OS, PFS, and ORR. For the landmark analysis, PFS and OS were calculated from 6 weeks after anti-PD-1/PD-L1 initiation.

SAS version v9.4 (Cary, NC, USA) was used to carry out the above analysis. All statistical tests were two-sided and statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics and outcomes

This analysis included 142 patients who received anti-PD-1/PD-L1-based treatments at DFCI. Baseline patient and disease characters are provided in Table 1. The median age was 61 years (range: 22–82), 84.5% (n = 120) of patients had clear cell histology, and 15.5% (n = 22) had sarcomatoid differentiation. Approximately 60% (n = 85) of the patients were intermediate risk, while 18.3% (n = 26) were favorable risk and 21.8% (n = 31) were poor risk. Sixty-two patients (43.7%) received treatment in the first-line setting, 37 (26.1%) in the second-line, and 43 (30.3%) received treatment in the third-line or later, with the majority receiving ICB monotherapy (n = 76, 53.5%). Overall, 91 patients received PD-1 based therapy (71 monotherapy, 20 combination therapy) and 51 received PD-L1 based therapy (5 monotherapy, 46 combination therapy). Forty-six patients received standard of care PD-1 monotherapy and 96 were treated as part of a clinical trial.

Table 1.

Patient and disease characteristics (N = 142)

| Number | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at start of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy | ||

| < 60 | 58 | 40.8 |

| ≥ 60 | 84 | 59.2 |

| Smoker | ||

| No | 69 | 48.6 |

| Yes | 72 | 50.7 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.7 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 41 | 28.9 |

| Male | 101 | 71.1 |

| Histology | ||

| Clear cell RCC | 120 | 84.5 |

| Non-clear cell RCC | 22 | 15.5 |

| Presence of Sarcomatoid | ||

| No | 119 | 83.8 |

| Yes | 22 | 15.5 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0.7 |

| Presence of Rhabdoid | ||

| No | 134 | 94.4 |

| Yes | 6 | 4.2 |

| Unknown | 2 | 1.4 |

| IMDC risk group at start of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy | ||

| Favorable | 26 | 18.3 |

| Intermediate | 85 | 59.9 |

| Poor | 31 | 21.8 |

| Line of therapy | ||

| 1 | 62 | 43.7 |

| 2 | 37 | 26.1 |

| ≥ 3 | 43 | 30.3 |

| Type of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy | ||

| Monotherapy | 76 | 53.5 |

| Combination therapy PD-L1 + VEGF targeted therapy (n = 46) PD-1 + VEGF-targeted therapy (n = 9) PD-1 + CTLA-4 (n = 7) PD-1 + other (n = 4) |

66 | 46.5 |

| Median | range | |

| NLR - baseline | 3.9 | 1.3–42.4 |

| NLR - week 6 | 4.1 | 1.1–96.4 |

The median NLR at baseline was 3.9 (range: 1.3–42.4) and 4.1 (range: 1.1–96.4) at 6 (±2) weeks. Median follow-up since initiation of the anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment was 16.6 (range: 0.7–67.8) months. Median duration on therapy was 5.1 (range: <1–61.4) months and 106 (74.6%) patients had discontinued the anti-PD-1/PD-L1-based treatments at time of analysis. The observed ORR rate was 31% (N = 44, 95% confidence interval (CI) 24–39). Median PFS and OS after therapy initiation were 7.3 (95% CI 3.5–8.8) months and 29.6 (95% CI 21.1–59.2) months, respectively.

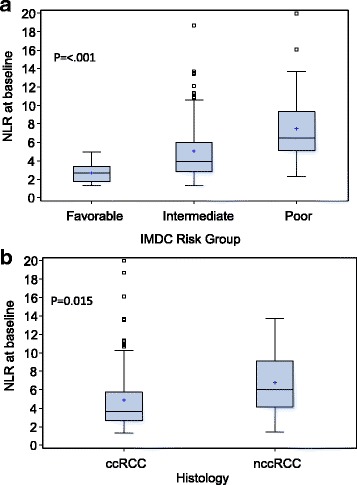

Associations of NLR with baseline characteristics

Baseline NLR levels were significantly higher in the poor IMDC risk group compared to those with favorable or intermediate risk (p < 0.001, Fig. 1a). Similarly, patients with non-clear cell histology had elevated NLR compared to those with clear cell histology (p = 0.015, Fig. 1b). We did not detect significant association of baseline NLR with other patient characteristics such as age, gender, smoker status, and line of therapy (p-values >0.15, data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) at start of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy by a IMDC risk groups and b Histology (clear cell RCC, ccRCC; non-clear cell RCC, nccRCC)

Prognostic role of pre-treatment NLR

The association of baseline NLR and treatment outcomes is presented in Table 2. Martingale residual plots confirmed the linearity of LnNLR (data not shown). A higher baseline NLR showed a trend toward lower ORR (adjusted odds ratio (OR) per 1 unit increase in lnNLR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.22–1.09, p = 0.081), shorter PFS (adjusted hazard ratio (HR) per 1 unit increase in lnNLR = 1.80, 95% CI 1.14–2.86, p = 0.012), and shorter OS (adjusted HR per 1 unit increase in lnNLR = 1.70, 95% CI 0.99–2.94, p = 0.056). The association of NLR at baseline and outcomes were consistent by type of ICB therapy (PD-1 vs PD-L1 based treatment) and by line of therapy (first line vs second line and beyond, data not shown).

Table 2.

Association of NLR at baseline, at 6-weeks, and change at week 6 (±2 weeks) with treatment outcomes in multivariable Cox and Logistic regression models

| ORR (CR + PR) | PFS | OS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N/ N response | Adjusted-ORb | p-value | Total N/ N event | Adjusted-HRb | p-value | Total N/ N event | Adjusted-HRb | p-value | |

| Continuous Ln(NLR) [baseline] | 142/44 | 0.49 (0.22–1.09) | 0.081 | 142/96 | 1.80 (1.14–2.86) | 0.012 | 142/51 | 1.70 (0.99–2.94) | 0.056 |

| Continuous Ln(NLR) [6-weeks]a | 134/44 | 0.22 (0.10–0.52) | 0.001 | 117/72 | 3.61 (2.21–5.88) | <0.001 | 134/46 | 2.51 (1.71–3.69) | <0.001 |

| NLR-change [6-weeks]a | |||||||||

| Decrease ≥25% | 28/12 | 1.52 (0.49–4.68) | 0.112 | 27/13 | 0.55 (0.26–1.18) | <0.001 | 28/6 | 0.33 (0.12–0.88) | 0.004 |

| No change | 58/21 | 1.00 (reference) | 53/30 | 1.00 (reference) | 58/18 | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Increase ≥25% | 48/11 | 0.45 (0.18–1.16) | 37/29 | 2.60 (1.53–4.39) | 48/22 | 1.57 (0.83–2.99) | |||

Abbreviations: ORR objective response rate, CR complete response, PR partial response, OR odds ratio, PFS progression free survival, HR hazard ratio, OS overall survival

aLandmark approach was used where OS and PFS were calculated from 6 weeks after therapy initiation. Patients who progressed before the 6 week landmark time were excluded for PFS analysis

bAdjusted for line of therapy, number of IMDC risk factors, histology (clear cell RCC vs non-clear cell RCC); baseline Ln(NLR) was also included as a covariate for the analysis of NLR change at 6 weeks. Boldface numerical values indicate statistically significant results

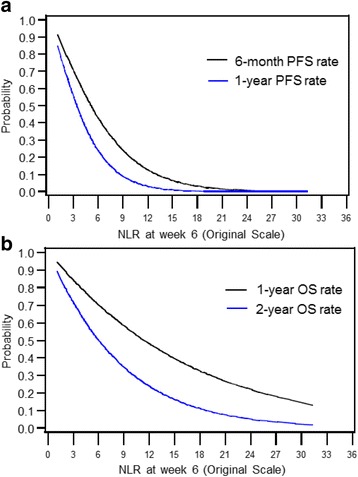

Prognostic role of NLR at 6 (±2) weeks

NLR at 6 weeks was a stronger predictor of all three outcomes (ORR, PFS, and OS) than baseline NLR (Table 2, Fig. 2). A higher 6 (±2) week NLR was independently associated with a lower ORR (Fig. 3a; adjusted OR per 1 unit increase in lnNLR = 0.22, 95% CI 0.10–0.52, p = 0.001), shorter PFS (adjusted HR per 1 unit increase in lnNLR = 3.61, 95% CI 2.21–5.88, p < 0.001), and shorter OS (adjusted HR per 1 unit increase in lnNLR = 2.51, 95% CI 1.71–3.69, p < 0.001). The association of NLR at 6 weeks and outcomes were consistent by type of ICB therapy and by line of therapy (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Estimated a 6-month and 1-year PFS rate, and b 1- and 2-year OS rate from Cox regression based on continuous neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) at week 6 (±2 weeks). NLR was modeled on the natural logarithmic scale and transformed back to the original scale for graphic presentation. PFS and OS were calculated from 6 weeks of therapy

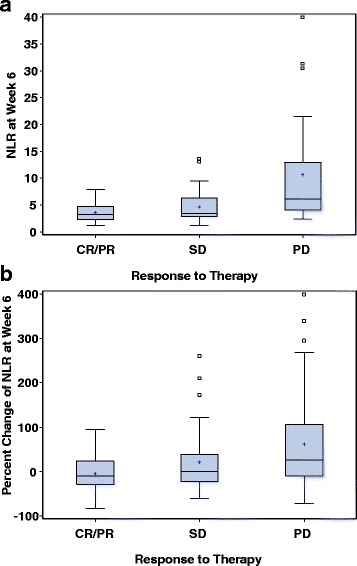

Fig. 3.

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) at week 6 (a) and percent (%) change of NLR at week 6 (b) according to response to therapy (complete/partial response, CR/PR; stable disease, SD; progressive disease, PD)

Prognostic role of a decline in NLR at 6 (±2) weeks

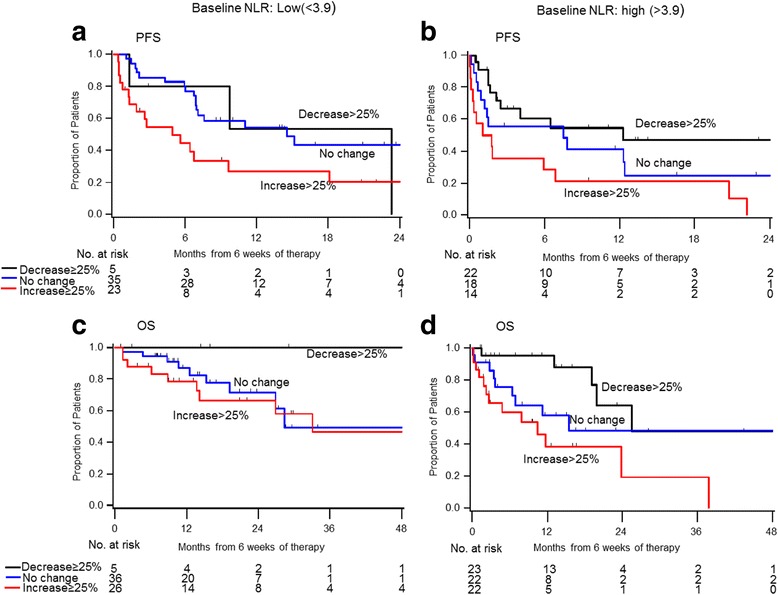

Relative NLR change from baseline to 6 (±2) weeks after anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy was an independent prognostic factor for PFS and OS (p < 0.001 and p = 0.004, respectively). A decrease ≥25% was associated with an improved PFS (adjusted HR = 0.55, 95% CI 0.26–1.18) and significantly better OS (adjusted HR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.12–0.88) when compared to the no change reference group (<25% decrease to <25% increase). By contrast, an NLR increase by ≥25% was associated with significantly worse PFS (adjusted HR = 2.60, 95% CI 1.53–4.39) and OS (adjusted HR = 1.57, 95% CI 0.83–2.99). Results were consistent in subgroup analysis by baseline NLR levels (low vs high, dichotomized at the median, Fig. 4). An NLR increase by ≥25% was associated with poorer PFS and OS, regardless of baseline NLR levels.

Fig. 4.

PFS and OS according to change of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) at 6 weeks, separately by baseline NLR status (Low vs High, dichotomized at the median)

Additionally, patients with an NLR increase ≥25% had numerically-lower ORR (Fig. 3b; OR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.18–1.16) while patients with a decrease in NLR ≥25% had numerically higher ORR rates (OR = 1.52, 95% CI 0.49–4.68), although these results were not significant (p = 0.112).

Discussion

In this analysis, we show that for mRCC patients treated with contemporary PD-1/PD-L1 ICB, higher 6-week NLR was independently associated with worse outcomes in terms of reduced ORR and shorter PFS and OS. In landmark analyses, we also demonstrate that early decline (decrease ≥25%) of NLR at 6-weeks was associated with an improved PFS and significantly better OS, whereas a relative increase by ≥25% was associated with poorer PFS and OS, regardless of baseline levels. Interestingly, while the results seen at baseline (pretreatment) NLR levels were statistically significant for PFS, the numerical values for OS and ORR in this study were nearly identical to results seen in a larger NLR analysis in mRCC patients treated with VEGF-TT [15]. Taken together, our data suggests that NLR appears to be a readily-available, prognostic marker in mRCC patients treated with conventional ICB, and warrants larger, prospective validation.

Our findings are consistent with and build upon previous reports evaluating NLR in solid tumors, including RCC [12–15]. In localized RCC, higher NLR at diagnosis (> 2.7, typically pre-nephrectomy) has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of recurrence [20]. However, a review by Boissier et al. suggests that in this localized RCC setting, NLR has not been shown to be significant for overall survival based on pooled data [21]. In locally-advanced or mRCC, higher NLR (typically >3) has been shown to be an independent prognostic factor for PFS and OS [21]. However, many of these studies were performed in the context of interleukin or IFN-based regimens. In subgroup analysis of the phase III S-TRAC study, which evaluated sunitinib versus placebo in patients with high-risk locoregional RCC post nephrectomy, baseline NLR ≤ 3 was associated with improved disease-free survival (DFS) with sunitinib compared to placebo (HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.54–0.95, p = 0.02), whereas NLR > 3 was not (HR 1.01, 95% CI 0.58–1.77, p = 0.96) [22]. Templeton et al. evaluated the utility of NLR in mRCC patients primarily treated with VEGF-TT and showed that, compared with no change, increase in NLR (≥25%) at week 6 was associated with poorer OS, PFS and reduced ORR whereas an early decline (decrease ≥25%) was associated with improved outcomes [15]. Regarding treatment with contemporary ICB, studies evaluating patients with melanoma or advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have shown that higher pretreatment NLR is associated with inferior OS and PFS [16–18]. However, we have performed the first analysis of the utility of NLR in mRCC patients treated in the current ICB era. Further, we similarly demonstrate the importance of changes in NLR during treatment and the prognostic relevance of measurements at week 6 independent of other factors. Given the expanding landscape and ongoing studies of PD-1/PD-L1-based therapies in mRCC [8, 23], accessible and affordable prognostic or predictive markers will continue to be a growing need.

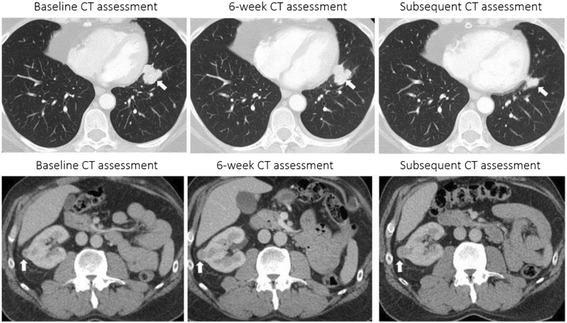

There are important clinical implications of our data particularly in the context of the unique and heterogenous radiographic findings in this patient population [24, 25]. While these results would benefit from prospective validation, the readouts at 6-weeks on ICB therapy are informative for both patients and physicians given that this time point typically coincides with the first set of re-staging scans after initiation of treatment. For example, if a patient presents at 6-weeks on therapy with stable or slightly progressive disease on imaging and a simultaneous decline in NLR, this may be reassuring to continue treatment assuming it is otherwise clinically suitable (Fig. 5, upper panels). Similarly, one may be more cautious regarding prognosis in a situation where a patient returns at 6-weeks with slightly progressive disease on imaging and a significant increase in NLR (Fig. 5, lower panels). Ultimately, the NLR is a helpful and available prognostic marker but should be considered in the context of other relevant clinical details when assessing the risk-benefit ratio of continuing ICB treatment at the individual patient level.

Fig. 5.

Computed tomography (CT) scans at baseline, 6-week, and subsequent assessment for two separate mRCC patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 ICB. The first patient (upper panels) had stable disease (SD) on 6-week scan with a 34% decrease in NLR from baseline and subsequently displayed partial response (PR) on next assessment. The second patient (lower panels) had SD on 6-week scan with a 113% increase in NLR from baseline and subsequently displayed progressive disease (PD) on next assessment. Arrows (white) show change in selected area of disease burden

Biologically, the NLR is a marker of systemic inflammation and potentially reflects the balance of the immune system in the context of a malignancy. The neutrophil count is thought to reflect the inflammatory microenvironment that in turn has tumor-promoting activity, including cancer cell survival and proliferation, angiogenesis and metastasis, as well as subversion of adaptive immune responses [26]. Lymphocytes are effective suppressors of cancer progression and their presence, particularly in the tumor microenvironment, is thought to reflect host immunity [27]. In a study of 35 advanced RCC patients treated predominantly with IFN, Sejima et al. showed an association of Fas ligand (FasL) expression in nephrectomy tumor cells with reduced lymphocyte count and thus higher NLR [28]. They explained this association by the concept of “FasL tumor counter-attack”, whereby FasL in tumor cells mediates tumor cell immune privilege by inducing apoptosis of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the microenvironment. On the other hand, this hypothesis has also been challenged, for example, with in vivo data [29]. Ultimately, this highlights the need for further prospective studies in patients treated with contemporary ICB, particularly with the added depth of next-generation sequencing and other informative technologies, to add more granularity to the biological underpinning of NLR in this setting.

These data should be interpreted in the context of the study design. First, this was a retrospective analysis which has the potential for selection bias and confounders. We attempted to control for this by utilizing a multivariable analysis to adjust for mRCC-specific prognostic variables that may impact analysis, including histology, line of therapy and IMDC risk factors. Our cohort included patients who were treated with PD-1 or PD-L1 ICB and there may be subtle differences between these drug pathways. For example, PD-1 inhibitors target PD-1:PD-L1 and PD-1:PD-L2, whereas PD-L1 inhibitors target PD-1:PD-L1 and PD-L1:B7.1 [30, 31]. While these slight mechanistic differences did not significantly affect our overall findings, prospective data would be informative particularly when evaluating single versus combination ICB therapy. Further, we could not control for concomitant medications that may have influenced white blood cell counts. Additionally, PD-L1 expression was not known in this retrospective analysis and may be a worthy point of future prospective study given the utility of this tissue biomarker continues to evolve in mRCC. Finally, similar to previous work investigating NLR in mRCC patients treated with VEGF-TT [15], data from untreated patients were not available in our analysis and thus it was not possible to assess the potential predictive value of NLR at baseline or on therapy.

Conclusion

In our cohort of mRCC patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 based immune checkpoint blockade, higher 6-week NLR was independently associated with a worse ORR and shorter PFS and OS. Early decline of NLR was associated with an improved PFS and significantly better OS, whereas a relative increase of NLR was associated with poorer PFS and OS, regardless of baseline levels. The NLR appears to be a readily-available, affordable, prognostic marker in mRCC patients treated with immune checkpoint blockade and warrants larger, prospective validation.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Kidney SPORE, and the Trust Family, Michael Brigham, and Loker Pinard Funds for Kidney Cancer Research at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for Toni K. Choueiri.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ccRCC

clear cell RCC

- ICB

Immune checkpoint blockade

- IFN-α

Interferon alfa

- IMDC

International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC)

- lnNLR

Natural log-transformed NLR

- mRCC

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma

- nccRCC

Non-clear cell RCC

- NLR

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- ORR

Objective response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PD-1

Programmed cell death protein-1

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- VEGF-TT

VEGF targeted therapies

Authors’ contributions

AAL, WX, and TKC were involved in the study design and concept. AAL, DJM, JAS, CKN, KMK, and AD were involved in the identification and selection of patients. AAL, WX, CJC, TKC were involved in the statistical analysis. AAL, WX, DJM were involved in the drafting of the manuscript. All authors were involved in the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors information

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the local institutional review boards and was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Declaration of Helskinki.

Consent for publication

Informed consent for publication has been obtained and the consent forms are held by the authors.

Competing interests

AAL: honoraria/consulting from Novartis; conference travel expenses from Pfizer.

WX: honoraria/consulting from Bayer.

JB: honoraria/consulting from Astellas, Genentech, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre; institutional research funding/support from Millenium, Sanofi, MSD Oncology, Pfizer.

EMVA: honoraria/consulting from Genome Medical, Novartis, Roche, Syapse, Takeda, Third Rock Ventures; institutional research funding/support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis.

BAM: honoraria/consulting from Astellas, Seattle Genetics, Bayer, Astra-Zeneca, Genentech and Exelixis.

LCH: honoraria/consulting from Genentech, Pfizer, Dendreon, NCCN, Medivation/Astellas, KEW, Corvus, Merck; institutional research funding/support from Bayer, Medivation/Astellas, Pfizer, Dendreon, Sotio, Genentech, Merck, BMS, Jannsen.

TKC: honoraria/consulting from Alligent, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cerulean Pharma, Eisai, Exelixis, Foundation Medicine, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Peloton, Pfizer, Prometheus, Roche/Genentech; institutional research funding/support from Pfizer, Exelixis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Peloton, AstraZeneca, Agensys, TRACON.

The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Aly-Khan A. Lalani, Email: Aly-Khan_Lalani@DFCI.HARVARD.EDU

Wanling Xie, Email: wxie@jimmy.harvard.edu.

Dylan J. Martini, Email: dylan.martini@emory.edu

John A. Steinharter, Email: JohnA_Steinharter@DFCI.HARVARD.EDU

Craig K. Norton, Email: craig.norton@umassmed.edu

Katherine M. Krajewski, Email: kmkrajewski@bwh.harvard.edu

Audrey Duquette, Email: Audrey_Duquette@DFCI.HARVARD.EDU.

Dominick Bossé, Email: Dominick_Bosse@DFCI.HARVARD.EDU.

Joaquim Bellmunt, Email: Joaquim_Bellmunt@DFCI.HARVARD.EDU.

Eliezer M. Van Allen, Email: EliezerM_VanAllen@DFCI.HARVARD.EDU

Bradley A. McGregor, Email: Bradley_McGregor@DFCI.HARVARD.EDU

Chad J. Creighton, Email: creighto@bcm.edu

Lauren C. Harshman, Email: LaurenC_Harshman@DFCI.HARVARD.EDU

Toni K. Choueiri, Phone: (617) 632-5456, Email: Toni_Choueiri@dfci.harvard.edu

References

- 1.Motzer RJ, Jonasch E, Agarwal N, et al. Kidney cancer, version 2.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2017;15(6):804–834. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, et al. Interferon alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:289–296. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mekhail TM, Abou-Jawde RM, Boumerhi G, et al. Validation and extension of the memorial Sloan-Kettering prognostic factors model for survival in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:832–841. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5794–5799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.4809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Food & Drug Administration https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm473971.htm. Accessed 26 Oct 2017.

- 7.European Medicines Agency http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2016/02/news_detail_002478.jsp. Accessed 26 Oct 2017.

- 8.Escudier B, Tannir N, McDermott DF, et al. CheckMate-214: efficacy and safety of nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib for treatment naïve advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_5):v605–v649. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx440.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.el-Hag A, Clark RA. Immunosuppression by activated human neutrophils. Dependence on the myeloperoxidase system. J Immunol. 1987;139:2406–2413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrie HT, Klassen LW, Kay HD. Inhibition of human cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity in vitro by autologous peripheral blood granulocytes. J Immunol. 1985;134:230–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Seruga B, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju124. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMillan DC. The systemic inflammation-based Glasgow prognostic score: a decade of experience in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39:534–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donskov F. Immunomonitoring and prognostic relevance of neutrophils in clinical trials. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Templeton AJ, Knox JJ, Lin X, et al. Change in neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in response to targeted therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma as a prognosticator and biomarker of efficacy. Eur Urol. 2016;70(2):358–356. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bagley SJ, Kothari S, Aggarwal C, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a marker of outcomes in nivolumab-treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2017;106:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lino-Silva LS, Salcedo-Hernández RA, García-Pérez L, et al. Basal neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with overall survival in melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2017;27(2):140–144. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang X, Du P, Yang Y. The clinical use of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in bladder cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Oncol. 2017; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohno Y, Nakashima J, Ohori M, et al. Followup of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and recurrence of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2012;187:411–417. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boissier R, Campagna J, Branger N, et al. The prognostic value of the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in renal oncology: a review. Urol Oncol. 2017;35(4):135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motzer RJ, Ravaud A, Patard JJ, et al. Adjuvant sunitinib for high-risk renal cell carcinoma after nephrectomy: subgroup analyses and updated overall survival results. Eur Urol. 2017; [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Choueiri TK, Motzer RJ. Systemic therapy for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:354–366. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1601333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Velasco G, Krajewski KM, Albiges L, et al. Radiologic heterogeneity in responses to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4(1):12–17. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiou VL, Burotto M. Pseudoprogression and immune-related response in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(31):3541–3543. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gooden MJ, de Bock GH, Leffers N, et al. The prognostic influence of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:93–103. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sejima T, Iwamoto H, Morizane S, et al. The significant immunological characteristics of peripheral blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and Fas ligand expression incidence in nephrectomized tumor in late recurrence from renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(7):1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donskov F, von der Maase H, Marcussen N, et al. Fas ligand expression in metastatic renal cell carcinoma during interleukin-2 based immunotherapy: no in vivo effect of Fas ligand tumor counterattack. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7911–7916. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JM, Chen DS. Immune escape to PD-L1/PD-1 blockade: seven steps to success (or failure) Ann Oncol. 2016;27(8):1492–1504. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JY, Lee HT, Shin W, et al. Structural basis of checkpoint blockade by monoclonal antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13354. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.