Abstract

Background:

Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (anti-NMDAR) encephalitis is a treatable autoimmune neurologic syndrome that occurs with or without tumor association. However, some severe cases are refractory to systemic immunotherapy. This pilot study aimed to evaluate the utility and safety of intrathecal methotrexate injection for severe patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis who did not respond to first-line immunotherapy.

Methods:

Intrathecal injections with methotrexate and dexamethasone were performed weekly in four legible patients within consecutive 4 weeks. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected at baseline and each time of intrathecal injection for identification of anti-NMDAR antibody titers.

Results:

Significant clinical improvement was observed in three patients associated with a stepwise decrease of CSF anti-NMDAR antibody titers (maximum: 1/320 to minimum: 1/10). After 2 months of follow-up, they were able to follow simple commands and had appropriate interactions with people (modified Rankin scale [mRS] of 0–2). At 12 months of follow-up, they all had returned to most activities of daily life (mRS of 0), and no relapses were reported. One patient showed no clinical improvement and died of neurologic complications.

Conclusions:

Intrathecal treatment may be a potentially useful supplementary therapy in severely affected patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Further large cohort study and animal experiment may help us elaborate the utility of intrathecal injection of methotrexate and its mechanism of action.

Keywords: Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate Receptor Encephalitis, Injections, Methotrexate

INTRODUCTION

Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis is an autoimmune neurologic syndrome characterized by multistage progression of symptoms including psychosis, memory deficits, seizures, and decreased level of consciousness along with autonomic instability.[1] Most patients had substantial recovery from the treatment of tumor resection and immunotherapy, which were associated with a decline of antibody titers. However, other patients remain severely disabled or die.[1,2] In a large cohort study, multivariable analysis revealed that the factors associated with good outcome included no need for Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and early treatment.[3]

In clinical settings, some patients fail to respond to first-line immunotherapy including steroids, intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIgs), and plasmapheresis alone or combined and progress rapidly into a state of unresponsiveness, requiring prolonged ICU stay. For these patients, the treatment strategy is not well established. Tatencloux et al.[4] reported three children with severe anti-NMDAR encephalitis who did not respond to first-line immunotherapy and second-line immunotherapy (including rituximab or azathioprine) and described their response to the intrathecal injection of methotrexate and methylprednisolone. The efficacy of intrathecal treatment has been seldom explored in anti-NMDAR encephalitis resistant to first-line immunotherapy. This pilot study aimed to evaluate the utility and safety of intrathecal methotrexate injection for severe patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis who did not respond to first-line immunotherapy.

METHODS

Ethical approval

The study was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ID: ChiCTR-OPC-16008478). This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (No. 251028). Written consent for studies was obtained from the patient's representatives.

Participants

Patients with a clinical diagnosis of anti-NMDAR encephalitis were eligible for participation in the study if they were more than 12 years of age, showed unsuccessful recovery from first-line immunotherapy with IVIg or intravenous high-dose steroids. Neurological status was assessed with the modified Rankin scale (mRS) at baseline and each time of intrathecal injection. First-line immunotherapy was considered a failure if no sustained improvement occurred within 8 weeks after two cycles of first-line immunotherapy and tumor removal when indicated, and if the mRS score remained 5.

All patients underwent brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), screening tests for any underlying neoplasm, and serological or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies that ruled out other disorders. Patients were excluded from participation if connective tissue disease or infectious encephalopathy was identified, severe dysfunction of liver, kidney, and digestive tract or serious systemic infection existed, or allergy to methotrexate reported.

Treatment

The therapeutic regimen consisted of intrathecal immunotherapy and systemic immunotherapy. Intrathecal injection was performed weekly within consecutive 4 weeks. All patients had routine blood tests before each intrathecal treatment including white blood cell (WBC) count, renal function, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and hypersensitive C-reactive protein (hsCRP). Intrathecal treatment could be administered only if there are no clinical (body temperature ≥38.5°C) or biological evidence of infection (hsCRP ≥5 mg/l, ESR ≥25 mm/h, and WBC ≥15,000/mm3) and serious renal insufficiency.

The whole procedure was performed with the patient supine and monitored. Equivalent volumes of CSF (usually 7–10 ml) were removed through lumbar puncture before intrathecal immunotherapy so as to minimize any change in CSF volume. Methotrexate 10 mg (Pfizer (Perth) Pty Limited, Australia) was then instilling over a period of 3–5 min and immediately followed by administration of 10 mg of dexamethasone (Tianjin Kingyork Group Co., Ltd., China) over 3–5 min. The remaining CSF was sent for cytology and antibody studies.

Systemic immunotherapy including low-dose steroids and mycophenolate mofetil was continued and decided by treating group according to patients’ condition. After the fourth intrathecal injection, it is recommended to continue the immunosuppression with mycophenolate mofetil and low-dose corticosteroids.

Antibody studies

Serum and CSF were collected at baseline and each time of intrathecal injection. Anti-NMDAR antibodies were evaluated using the indirect immunofluorescence test kit autoimmune encephalitis mosaic 1 (catalog no. FA 112d-1, Euroimmun Ag, Germany). Samples were considered positive if three immunohistochemical criteria were fulfilled.[2] Antibody titers were measured with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay on HEK293 cell lysates ectopically expressing NR1 or NR1–NR2B heteromers.[2]

Follow-up

Patients were followed up at outpatient clinic for at least 12 months after the initiation of intrathecal treatment. Neurological status was assessed with mRS at a regular interval (1, 3, and 6 months). Relapse of encephalitis was defined as the new onset or worsening of symptoms occurring after at least 2 months of improvement or stabilization. All patients underwent detailed neurological examination and MRI at up to 6 months after intrathecal treatment to detect any subclinical methotrexate-induced toxicity including chemical meningitis, delayed leukoencephalopathy, and transverse myelopathy.

RESULTS

Totally, four patients referred to Peking Union Medical College Hospital were enrolled from January 2015 to January 2016. The median age of onset was 17.8 years (range: 13.0–23.0 years). All the patients had prodromal symptoms consisting of headache, low-grade fever, or a nonspecific viral-like illness within 1 week before admission. They all progressed rapidly into a state of unresponsiveness within 2 weeks [Table 1].

Table 1.

Characteristics and clinical features of the four enrolled patients

| Items | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | Male | Female | Female |

| Age at onset (years) | 23 | 16 | 13 | 19 |

| Prodromal symptoms | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Initial symptoms | Seizure | Psychosis | Psychosis | Psychosis |

| Seizures | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Psychiatric symptoms | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Movement disorders | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time from onset to unresponsiveness (days) | 10 | 7 | 7 | 4 |

| Autonomic instability | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Central hypoventilation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| EEG | Extreme delta brush | Diffuse slowing | Diffuse slowing | Diffuse slowing |

| Brain CT | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Brain MRI | Normal | Normal | * | N/A |

| CSF | ||||

| Lymphocytic pleocytosis | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Increased protein | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Oligoclonal bands | Positive | Negative | Weak positive | Positive |

EEG: Electroencephalograph; CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid. *Atrophy of frontal and temporal lobe. N/A: Not applicable.

The four patients had long-term electroencephalograph monitoring, which showed generalized slow or disorganized activity without epileptic discharges. Unilateral ovarian teratoma was detected and removed in three patients, of which the histopathology revealed mature cystic teratoma.

The longest time from presentation to initial treatment was 23 days (Case 1), with a mean time of 11 days. The four patients remained comatose after receiving intravenous corticosteroids and at least two courses of IVIg as first-line immunotherapy (mRS = 5) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Treatments received in each patient before intrathecal treatment

| Items | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time from presentation to treatment (days) | 23 | 5 | 10 | 6 |

| Tumour resection | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| Teratoma | Unilateral ovary | N/A | Unilateral ovary | Unilateral ovary |

| Immunotherapy | ||||

| Methylprednisolone | 1000 mg/d × 5 days | 500 mg/d × 3 days | 1000 mg/d × 3 days | 500 mg/d × 5 days |

| IVIg, course | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Plasma exchange | No | No | No | No |

| Rituximab | 375 mg/m2 | No | No | No |

| Cyclophosphamide | No | No | No | No |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | No | No | 1000 mg/d | No |

| Intensive care | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ventilation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

IVIg: Intravenous immunoglobulins. N/A: Not applicable.

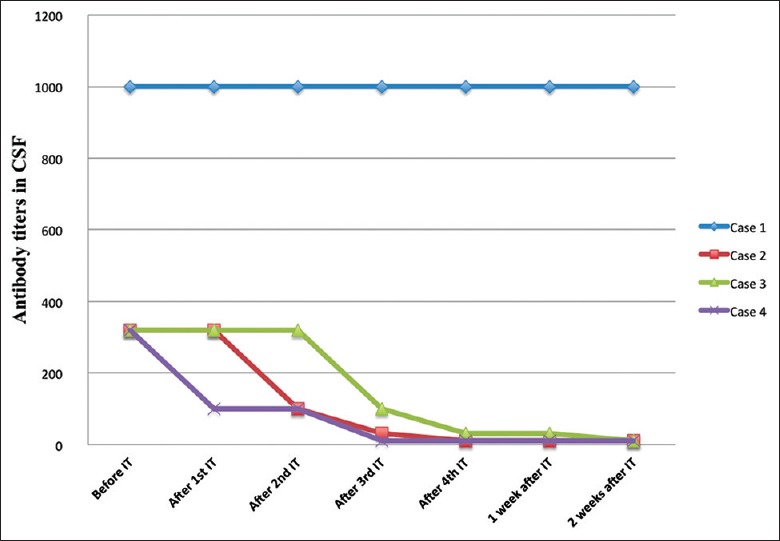

The four patients underwent intrathecal methotrexate treatment with an adapted protocol within 4 weeks. Intravenous methylprednisolone was given at a daily dose of 40–60 mg during the period of intrathecal treatment. Three patients (Case 2, Case 3, and Case 4) gradually waked from coma and were weaned from mechanical ventilation following the fourth intrathecal injections, associated with a step-wise decrease of CSF anti-NMDAR antibody titers [Figure 1]. After 2 months of follow-up, they were able to follow simple commands and had appropriate interactions with people (mRS of 0–2). At 12 months of follow-up, they all had returned to most activities of daily life (mRS of 0), and no relapses were reported. Nevertheless, Case 1 showed no clinical improvement while there was a persistent high level of antibodies in the CSF. The patient remained in a state of immobilization after 2 months of follow-up and died of neurologic complications. Table 3 demonstrated the changes in mRS scores of each patient.

Figure 1.

Changes in antibody titers in cerebrospinal fluid before and after intrathecal treatment. IT: Intrathecal injection; CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid.

Table 3.

Changes in mRS scores in each patient

| Items | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At diagnosis | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 2 weeks after immunotherapy | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Before IT | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 4 weeks after IT | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 months after IT | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 12 months after IT | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 |

mRS: Modified Rankin Scale; IT: Intrathecal injection. N/A: Not applicable.

DISCUSSION

Since its discovery in 2007, anti-NMDAR encephalitis has entered the mainstream of neurology. However, in the absence of prospective and randomized data, therapeutic strategies were recommended based on observational studies and clinical experience. In this study, significant clinical improvement was observed in three patients with a parallel decrease of CSF anti-NMDAR antibody titers after intrathecal treatment was added. This result was similar to the previous study reported.[4] Case 1 showed poor response to systemic and intrathecal immunotherapy. Delay of initial treatment may contribute to poor outcome in this patient.

According to Tatencloux et al.'s report,[4] intrathecal immunotherapy was motivated in children who showed an insufficient response or relapses to first- and second-line immunotherapy and with mRS score ≥3. Compared to that, our patients had a greater severity with mRS score of 5 after first-line immunotherapy. All the patients had prolonged ICU stay and required invasive mechanical ventilation.

As we know, patients with protracted symptoms usually have persistent levels of anti-NMDAR antibodies in the CSF.[2] A retrospective study indicated that antibody titer change in the CSF was more closely related with clinical outcome than was that in serum in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis.[5] In our study, the patients remained comatose after at least two cycles of first-line immunotherapy, accompanied by persistent high levels of anti-NMDAR antibodies in the CSF. CSF anti-NMDAR antibody titers became lower after the first or second intrathecal injections in this study. Subsequently, the significant clinical improvement was observed in three patients following the fourth intrathecal injections. The fluctuation of antibody titers correlated well with the clinical status of our patients. An early decrease of antibodies after intrathecal treatment may indicate a potential recovery of the patient.

Most patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis have intrathecal synthesis of NMDAR antibodies.[2,6,7] Compelling clinical and laboratory evidence exists that anti-NMDAR antibodies are pathogenic. Hughes et al.[8] indicated that anti-NMDAR antibodies cause a selective and reversible loss of surface NMDA receptor by antibody-mediated capping and internalization, resulting in abrogation of NMDAR-mediated synaptic function. C-X-C motif chemokine 13 (CXCL13) is a B-cell-attracting chemokine that is found mildly elevated in autoimmune disorders such as multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica.[9,10] One study showed that 70% of patients with early-stage anti-NMDAR encephalitis had increased CSF CXCL13 concentration that correlated with intrathecal NMDAR-antibody synthesis.[11] Plasma cells or plasmablasts, both known to secrete high amounts of antibodies, were found in perivascular, interstitial, and Virchow-Robin spaces of brain, providing a histopathological explanation for the intrathecal synthesis of antibodies noted in anti-NMDAR encephalitis.[12]

These findings indicated that the therapeutic target is to eliminate the intrathecal antibody and reverse the disorder. It is reported that the patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis had preserved integrity of the blood–brain barrier (BBB).[2] However, IVIg, steroids, rituximab as well as cyclophosphamide, these drugs have limited BBB penetration which maybe a plausible explanation of the limited response to immunotherapy in patients with serious immune response and high level of synthesized antibodies in the central nervous system. It is suggested that treatment strategies that facilitate BBB penetration, such as high-dose methotrexate, may be useful in patients with refractory symptoms and persistently elevated CSF antibody titers.[13]

Intrathecal treatment is an established therapeutic protocol used for the treatment of leukemia, lymphoma, and carcinomatosis with central nervous system involvement.[14,15,16] Methotrexate is the chemotherapeutic agent most commonly used for intrathecal therapy. A variety of neurologic complications can result from intrathecal methotrexate therapy. These include aseptic meningitis,[17] delayed leukoencephalopathy, acute encephalopathy,[18,19] and transverse myelopathy.[20] However, no such toxicity was detected in any of our patients during hospitalization and 12-month follow-up.

There are unavoidable restrictions in the study. Our patients did not receive similar baseline treatment since treatment decision was made at the physician's discretion. Most of the patients admitted to our hospital improved within the first 8 weeks of first-line therapy. Only for severely affected patients, who showed no response to first-line immunotherapy and required intensive care support for several months, intrathecal methotrexate treatment seemed to be a reasonable option. Ultimately, only a limited number of cases were enrolled in this study, which had diminished the statistical power in the results.

Nevertheless, it seemed that the intrathecal methotrexate injection contributed to the neurological recovery and the parallel decrease of antibody titers. We postulate that intrathecal injection may have a direct impact on the inflammatory environment, helping suppress the intrathecal synthesis of antibodies and resulting in the decrease of antibody titers and clinical improvement. This may help shorten ICU stay and reduce a large amount of medical expense. Intrathecal treatment may be a potentially useful supplementary therapy in severely affected patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Further large cohort study and animal experiment may help us elaborate the utility of intrathecal methotrexate treatment and its mechanism of action.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by grants from PUMC Youth Fund (3332016004), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (3332016004), and Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Foundation (Z161100000516094).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the patients and their families.

Footnotes

Edited by: Yuan-Yuan Ji

REFERENCES

- 1.Dalmau J, Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, Rosenfeld MR, Balice-Gordon R. Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:63–74. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70253-2. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70253-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalmau J, Gleichman AJ, Hughes EG, Rossi JE, Peng X, Lai M, et al. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis: Case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1091–8. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70224-2. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70224-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Titulaer MJ, McCracken L, Gabilondo I, Armangué T, Glaser C, Iizuka T, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: An observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:157–65. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70310-1. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70310-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tatencloux S, Chretien P, Rogemond V, Honnorat J, Tardieu M, Deiva K, et al. Intrathecal treatment of anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis in children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57:95–9. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12545. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gresa-Arribas N, Titulaer MJ, Torrents A, Aguilar E, McCracken L, Leypoldt F, et al. Antibody titres at diagnosis and during follow-up of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: A retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:167–77. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70282-5. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70282-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irani SR, Bera K, Waters P, Zuliani L, Maxwell S, Zandi MS, et al. N-methyl-D-aspartate antibody encephalitis: Temporal progression of clinical and paraclinical observations in a predominantly non-paraneoplastic disorder of both sexes. Brain. 2010;133:1655–67. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq113. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prüss H, Dalmau J, Arolt V, Wandinger KP. Anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis. An interdisciplinary clinical picture. Nervenarzt. 2010;81:396, 398, 400. doi: 10.1007/s00115-009-2908-9. doi: 10.1007/s00115-009-2908-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes EG, Peng X, Gleichman AJ, Lai M, Zhou L, Tsou R, et al. Cellular and synaptic mechanisms of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5866–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0167-10.2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0167-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khademi M, Kockum I, Andersson ML, Iacobaeus E, Brundin L, Sellebjerg F, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid CXCL13 in multiple sclerosis: A suggestive prognostic marker for the disease course. Mult Scler. 2011;17:335–43. doi: 10.1177/1352458510389102. doi: 10.1177/1352458510389102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong X, Wang H, Dai Y, Wu A, Bao J, Xu W, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of CXCL13 are elevated in neuromyelitis optica. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;240-241:104–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.10.001. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leypoldt F, Höftberger R, Titulaer MJ, Armangue T, Gresa-Arribas N, Jahn H, et al. Investigations on CXCL13 in anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis: A potential biomarker of treatment response. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:180–6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.2956. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camdessanché JP, Streichenberger N, Cavillon G, Rogemond V, Jousserand G, Honnorat J, et al. Brain immunohistopathological study in a patient with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:929–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03180.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez-Hernandez E, Horvath J, Shiloh-Malawsky Y, Sangha N, Martinez-Lage M, Dalmau J, et al. Analysis of complement and plasma cells in the brain of patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Neurology. 2011;77:589–93. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318228c136. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318228c136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124–31. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dufourg MN, Landman-Parker J, Auclerc MF, Schmitt C, Perel Y, Michel G, et al. Age and high-dose methotrexate are associated to clinical acute encephalopathy in FRALLE 93 trial for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. Leukemia. 2007;21:238–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404495. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haddad E, Sulis ML, Jabado N, Blanche S, Fischer A, Tardieu M, et al. Frequency and severity of central nervous system lesions in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 1997;89:794–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geiser CF, Bishop Y, Jaffe N, Furman L, Traggis D, Frei E, 3rd, et al. Adverse effects of intrathecal methotrexate in children with acute leukemia in remission. Blood. 1975;45:189–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhojwani D, Sabin ND, Pei D, Yang JJ, Khan RB, Panetta JC, et al. Methotrexate-induced neurotoxicity and leukoencephalopathy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:949–59. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0808. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang J, Kim GS, Park HM. A unique radiological case of intrathecal methotrexate-induced toxic leukoencephalopathy. J Neurol Sci. 2015;353:169–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.04.001. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murata KY, Maeba A, Yamanegi M, Nakanishi I, Ito H. Methotrexate myelopathy after intrathecal chemotherapy: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:135. doi: 10.1186/s13256-015-0597-5. doi: 10.1186/s13256-015-0597-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]