Abstract

Pretreatment of low-dose lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induces a hyporesponsive state to subsequent secondary challenge with high-dose LPS in innate immune cells, whereas super-low-dose LPS results in augmented expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. However, little is known about the difference between super-low-dose and low-dose LPS pretreatments on immune cell-mediated inflammatory and hepatic acute-phase responses to secondary LPS. In the present study, RAW 264.7 cells, EL4 cells, and Hepa-1c1c7 cells were pretreated with super-low-dose LPS (SL-LPS: 50 pg/mL) or low-dose LPS (L-LPS: 50 ng/mL) in fresh complete medium once a day for 2~3 days and then cultured in fresh complete medium for 24 hr or 48 hr in the presence or absence of LPS (1~10 μg/mL) or concanavalin A (Con A). SL-LPS pretreatment strongly enhanced the LPS-induced production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, TNF-α/IL-10, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and nitric oxide (NO) by RAW 264.7 cells compared to the control, whereas L-LPS increased IL-6 and NO production only. SL-LPS strongly augmented the Con A-induced ratios of interferon (IFN)-γ/IL-10 in EL4 cells but decreased the LPS-induced ratios of IFN-γ/IL-10 compared to the control, while L-LPS decreased the Con A- and LPS-induced ratios of IFN-γ/IL-10. SL-LPS enhanced the LPS-induced production of IL-6 by Hepa1c1c-7 cells compared to the control, while L-LPS increased IL-6 but decreased IL-1β and C reactive protein (CRP) levels. SL-LPS pretreatment strongly enhanced the LPS-induced production of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, PGE2, and NO in RAW 264.7 cells, and the IL-6, IL-1β, and CRP levels in Hepa1c1c-7 cells, as well as the ratios of IFN-γ/IL-10 in LPS- and Con A-stimulated EL4 cells compared to L-LPS. These findings suggest that pre-conditioning of SL-LPS may contribute to the mortality to secondary infection in sepsis rather than pre-conditioning of L-LPS.

Keywords: Endotoxin pretreatment, Proinflammatory cytokines, Prostaglandin E2, Nitric oxide, Acute-phase protein

INTRODUCTION

Endotoxin, a heat-stable cell wall component of gram-negative bacteria, is characterized by robust induction of the systemic inflammatory response in the innate immune system via the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) pathway, which can lead to shock, cell damage, and potentially multiple organ failure (1,2). Endotoxin stimulates the overproduction of pro-inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, interferon (IFN)-γ, and C-reactive protein (CRP), resulting in an acute inflammatory response. Via an inhibitory feedback effect, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) also induces anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 (3,4). However, pre-exposure of innate immune cells such as macrophages to low-dose LPS (L-LPS, > 10 ng/mL) fails to induce the robust expression of proinflammatory mediators to subsequent endotoxin challenge, a phenomenon known as endotoxin tolerance (5). Endotoxin tolerance leads to a shift away from a pro-inflammatory response, including production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and PGE2, toward a response with key anti-inflammatory features via IL-10 production. Even though endotoxin tolerance is known to protect animals from infection, endotoxin tolerance-induced immunosuppression on the innate immune response, which is clinically observed in sepsis patients, is associated with worse outcomes, including mortality (6).

Pretreatment of super-low-dose LPS (SL-LPS, < 100 pg/mL) exhibits increased mortality in response to secondary challenge with a higher dose of LPS (7,8). Endotoxin priming that is characterized by subclinical SL-LPS causes a distinct effect by priming monocytes/macrophages for a more robust response to a secondary LPS challenge, a phenomenon known as the “Shwartzman reaction” (2,7,9). This endotoxin priming response has been shown to augment the LPS-induced production of in vitro pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α (7,9). SL-LPS removed transcriptional suppressors on the promoters of pro-inflammatory genes, resulting in the mild but persistent expression of pro-inflammatory mediators (10).

The activation of innate immune cells by LPS or LPS-induced inflammatory mediators can result in the development of adaptive immunity and acute-phase responses. The balance between T helper (Th)1 and Th2 cytokines is associated with the ultimate outcome of the cell-mediated immune response. IFN-γ, which is a Th1 cytokine produced by natural killer cells and activated T cells, mediates host defense against infection via activation of macrophages, whereas IL-10 plays a role in the Th2 response (11). Endotoxic shock mortality is also increased via downregulation of the Th1 response and endogenous IFN-γ as well as the innate immune response (12). Endotoxin tolerance is associated with profound impairment in the ability to produce IFN-γ in response to exposure to an endotoxin. In contrast, elevation of endogenous IFN-γ increases the mortality rate, but anti-IFN-γ induces a protective effect from endotoxic shock (13). However, because the immunoparalysis in sepsis has been reported to be partially restored by therapy with recombinant IFN-γ (14), elevated IFN-γ may also play a role in the induction of the T cell-mediated proinflammatory response via an IFN-γ-activated innate immune response.

Increased gut permeability, changes in the composition and diversity of the gut microbiome, and chronic stress have been proposed as possible mechanisms to explain the increased levels of circulating endotoxins in metabolic syndrome (15,16). Metabolic endotoxemia is described as a condition of low-grade elevation of plasma LPS at levels 10~50-times lower than those observed during septic conditions (17). The liver is also associated with high exposure to circulating endotoxins from the gut microbiota, consequently resulting in metabolic endotoxemia (18). Circulating levels of SL-LPS may contribute to the development of a metabolic disorder in the liver via upregulation of acute-phase proteins, which alter the function of the liver and contribute to inflammatory and coagulation processes in sepsis (19). Nevertheless, precisely how preconditioning of SL-LPS in sepsis influences the immune cell-mediated inflammatory response and hepatic acute-phase response to secondary infection remains poorly understood. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate if and how pretreatment of L-LPS and SL-LPS alters the inflammatory response to subsequent high-dose LPS in RAW 264.7 cells, Hepa-1c1c7 cells, and EL4 cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

RAW 264.7 cells, Hepa-1c1c7 cells, and EL4 cells were purchased from the Korean Cell Bank (Seoul, Korea).

Cell culture

RAW 264.7 cells, Hepa-1c1c7 cells, and EL4 cells were maintained in complete Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) and 1× antibiotic/antimycotic (Invitrogen). RAW 264.7 cells and EL4 cells were pretreated with 50 pg/mL or 50 ng/mL LPS in fresh complete medium once a day for 3 days, and the cells were then cultured for 24 hr in fresh complete medium in the presence or absence of 1 μg/mL LPS in RAW 264.7 cells, and with 10 μg/mL LPS or concanavalin A (Con A) (Sigma Chemical Co.) in EL4 cells at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Hepa-1c1c7 cells were pretreated with 50 pg/mL LPS in fresh complete medium once a day for 2 days, and new Hepa-1c1c7 cells were pretreated with 50 ng/mL LPS once on only the second day. Subsequently, both LPS-pretreated Hepa-1c1c7 cells were cultured in fresh complete medium for 24 hr or 48 hr in the presence of 10 μg/mL LPS. The cell supernatants were then harvested and stored at −70°C for cytokine, CRP, PGE2, and NO assays.

Cytokine assay

The concentrations of cytokines in the supernatants harvested from the culture in RAW 264.7 cells, Hepa-1c1c7 cells, and EL4 cells were determined using cytokine monoclonal antibodies (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, CA, USA). All measurements were carried out in tetraplicate. The results were measured in picograms per milliliter at 450 nm using an enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) microplate reader (Molecular Devices Co., Ltd., CA, USA). The lower limit of sensitivity for each ELISA was ≤ 5 pg/mL.

PGE2 immunoassay

The concentrations of PGE2 in the supernatants harvested from the RAW 264.7 cells culture were determined using a monoclonal antibody/enzyme immunoassay kit (Cayman Chemicals, MI, USA), according to the manufacturer instructions. Concentrations of PGE2 were measured at 405 nm using ELISA. The lower limit of sensitivity for each ELISA was ≤ 5 pg/mL.

NO assay

The concentrations of NO in the supernatants harvested from the culture in RAW 264.7 cells were assayed by adding 100 μL of freshly prepared Griess reagent to 100 μL of the sample in 96-well plates, and then the absorbance was read at 540 nm after 10 min using ELISA.

CRP assay

The concentrations of CRP in the supernatants harvested from the culture in Hepa1c1c-7 cell were determined using a CRP ELISA kit (R&D Systems Inc., MN, USA) according to the manufacturer instructions. Concentrations of CRP were measured at 450 nm using ELISA. The lower limit of sensitivity for each ELISA was ≤ 5 pg/mL.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. Experiments were always run in tetraplicate and repeated at least twice. Analysis of variance and Student’s t-test were used to determine statistical significance, and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effects of SL-LPS pretreatment on the LPS-induced production of cytokines by RAW 264.7 cells

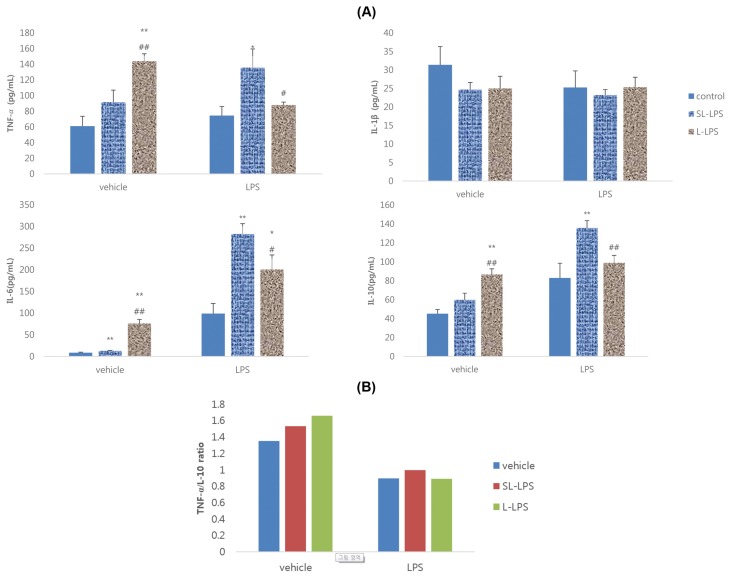

The primary aim of this study was to examine whether pretreatment of 50 pg/mL LPS (SL-LPS) enhances the production of cytokines by RAW 264.7 cells in the presence or absence of high-dose (1 μg/mL) LPS compared to 50 ng/mL LPS (L-LPS) pretreatment. As shown in Fig. 1A, pretreatment of L-LPS and SL-LPS significantly enhanced the production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 by RAW 264.7 cells in the absence of high-dose LPS compared to the control and SL-LPS treatments. However, in the presence of high-dose LPS, SL-LPS pretreatment remarkably enhanced the LPS-induced production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 by RAW 264.7 cells compared to the control, whereas L-LPS increased only the IL-6 level. SL-LPS pretreatment remarkably enhanced the LPS-induced production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 by RAW 264.7 cells compared to L-LPS. TNF-α/IL-10 ratios in RAW 264.7 cells without high-dose LPS were enhanced in cells that received pretreatment of SL-LPS or L-LPS in a concentration-dependent manner. The TNF-α/IL-10 ratios with LPS in the control, SL-LPS, and L-LPS groups were 0.90, 1.00, and 0.89, respectively (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Effects of LPS pretreatment on the LPS-induced production of cytokines in RAW 264.7 cells. (A) Cytokines; (B) TNF-α/IL-10 ratio. RAW 264.7 cells were pretreated with concentrations of LPS 50 pg/mL (SL-LPS) or LPS 50 ng/mL (L-LPS) with refresh complete media once a day for 3ds consequently and the cells were then cultured for 24 hr with refresh complete media in the presence or absence of LPS (1 μg/mL). Concentration of cytokines was measured using ELISA. These experiments were run in tetraplicate and repeated at least twice. Each value represents the mean ± SE. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. Significantly different from the value in each control. #p<0.05 and ##p < 0.01. Significantly different from the value in each SL-LPS.

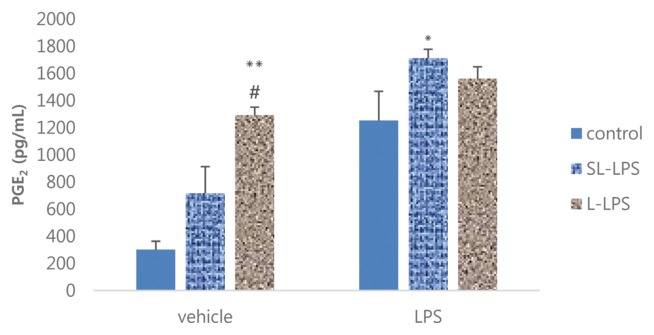

Effects of SL-LPS pretreatment on the LPS-induced production of PGE2 by RAW 264.7 cells

We next investigated the effect of pretreatment of SL-LPS and L-LPS on the production of PGE2 by RAW 264.7 cells in the presence or absence of 1 μg/mL LPS. In the absence of high-dose LPS, L-LPS pretreatment remarkably enhanced the production of PGE2 by RAW 264.7 cells compared to the control or SL-LPS group (Fig. 2). However, SL-LPS but not L-LPS pretreatment significantly augmented the LPS-induced production of PGE2 by RAW 264.7 cells compared to the control.

Fig. 2.

Effects of LPS pretreatment on the LPS-induced production of PGE2 in RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells were pretreated with concentrations of LPS 50 pg/mL (SL-LPS) or LPS 50 ng/mL (L-LPS) with refresh complete media once a day for 3ds consequently and the cells were then cultured for 24 hr with refresh complete media in the presence or absence of LPS (1 μg/mL). These experiments were run in tetraplicate and repeated at least twice. Each value represents the mean ± SE. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. Significantly different from the value in each control. #p < 0.05. Significantly different from the value in each SL-LPS.

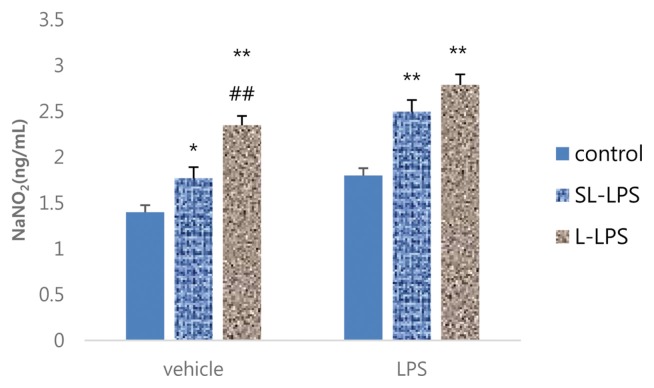

Effects of SL-LPS pretreatment on the LPS-induced production of NO by RAW 264.7 cells

The comparison between SL-LPS and L-LPS pretreatment on the LPS-induced production of NO by RAW 264.7 cells in the presence or absence of high-dose LPS (1 μg/mL) is summarized in Fig. 3. The pretreatment of both SL-LPS and L-LPS remarkably enhanced the production of NO by RAW 264.7 cells in the absence of high-dose LPS in a concentration-dependent manner compared to the control. The pretreatments of SL-LPS and L-LPS strongly enhanced the LPS-induced production of NO by RAW 264.7 cells in comparison to the control, but there was no statistically significant difference between the SL-LPS and L-LPS groups.

Fig. 3.

Effects of LPS pretreatment on the LPS-induced production of NO in RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells were pretreated with concentrations of LPS 50 pg/mL (SL-LPS) or LPS 50 ng/mL (L-LPS) with refresh complete media once a day for 3ds consequently and the cells were then cultured for 24 hr with refresh complete media in the presence or absence of LPS (1 μg/mL). These experiments were run in tetraplicate and repeated at least twice. Each value represents the mean ± SE. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. Significantly different from the value in each control. ##p < 0.01. Significantly different from the value in each SL-LPS.

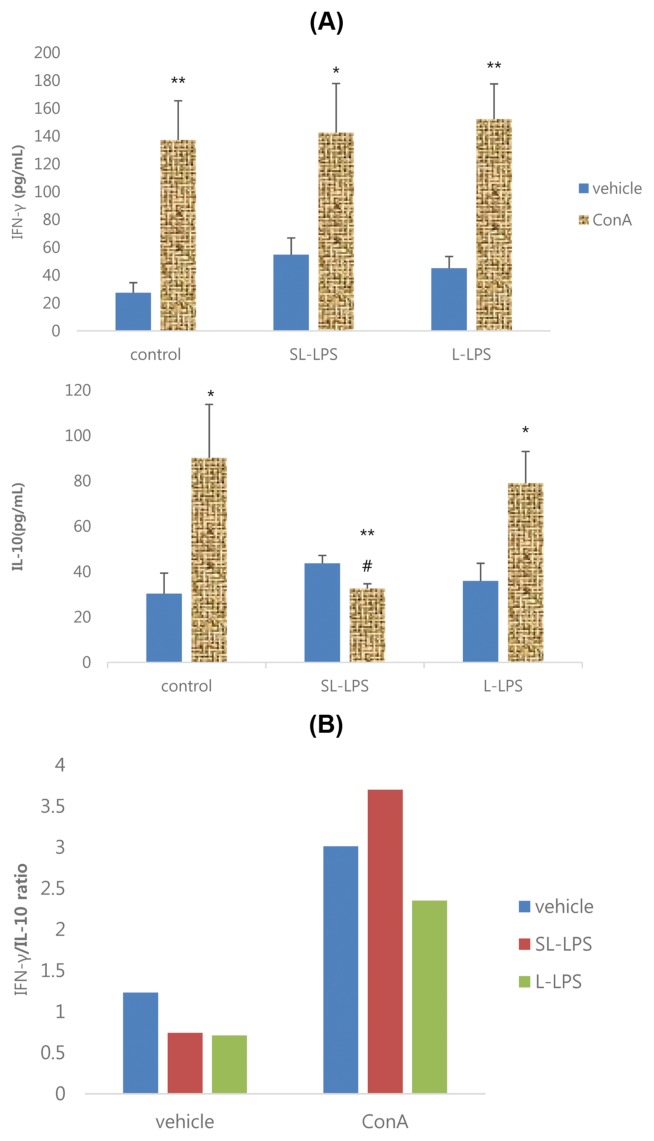

Effects of SL-LPS pretreatment on the Con A-induced production of cytokines by EL4 cells

The effects of SL-LPS and L-LPS pretreatment on the production of cytokines by EL4 cells in the presence or absence of 10 μg/mL Con A are summarized in Fig. 4. The results showed that the Con A-induced productivity of IFN-γ and IL-10 by EL4 cells was significantly increased in the control and L-LPS groups, while IFN-γ was increased but IL-10 was attenuated in the SL-LPS group (Fig. 4A). The IFN-γ/IL-10 ratios in Con A-stimulated EL4 cells in the control, SL-LPS, and L-LPS groups were 3.01, 3.70, and 2.35, respectively (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Effects of LPS pretreatment on the Con A-induced production of cytokines in EL4 cells. (A) Cytokine; (B) IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio. EL4 cells were pretreated with concentrations of LPS 50 pg/mL or LPS 50 ng/mL in refresh complete media once a day for 3ds consequently and the cells were then cultured for 24 hr with refresh complete media in the presence or absence of Con A 10 μg/mL. These experiments were run in tetraplicate and repeated at least twice. Each value represents the mean ± SE. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. Significantly different from the value in each vehicle. #p < 0.05. Significantly different from the value in positive control.

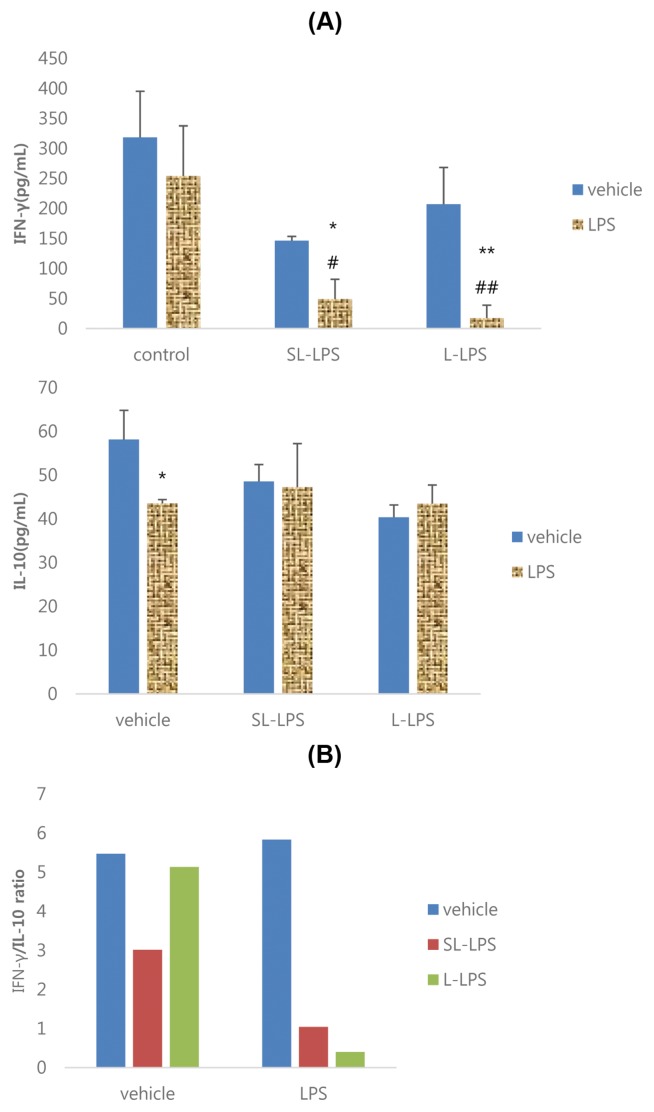

Effects of SL-LPS pretreatment on the LPS-induced production of cytokines by EL4 cells

As shown in Fig. 5A, 10 μg/mL LPS remarkably attenuated the production of IL-10 by EL4 cells in the control but, whereas it attenuated IFN-γ but not IL-10 in the SL-LPS and L-LPS groups. The IFN-γ/IL-10 ratios in LPS-stimulated EL4 cells in the control, SL-LPS, and L-LPS groups were 5.83, 1.04, and 0.40, respectively (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Effects of LPS pretreatment on the LPS-induced production of cytokines in EL4 cells. (A) Cytokine; (B) IFN-γ/IL-10 ratio. EL4 cells were pretreated with concentrations of LPS 50 pg/mL or LPS 50 ng/mL in refresh complete media per each day for 3ds consequently and the cells were then cultured for 24 hr with refresh complete media in the presence or absence of LPS (10 μg/mL). These experiments were run in tetraplicate and repeated at least twice. Each value represents the mean ± SE. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. Significantly different from the value in each vehicle. #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01. Significantly different from the value in positive control.

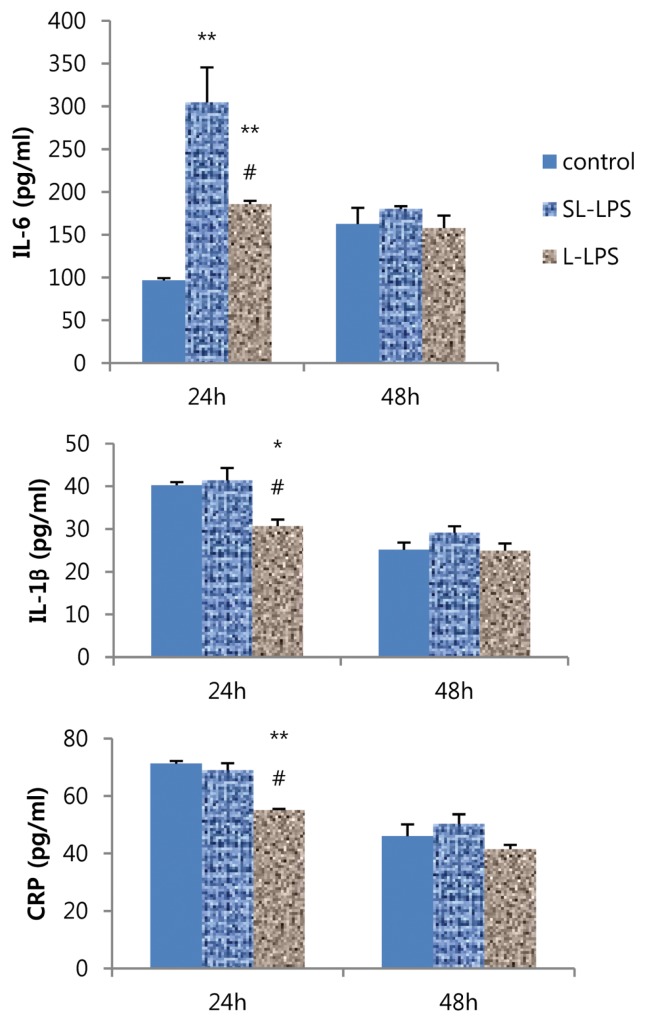

Effects of SL-LPS pretreatment on the LPS-stimulated production of cytokines and CRP by Hepa-1c1c7 cells

Finally, we investigated the effects of SL-LPS and L-LPS pretreatment on the LPS-induced production of hepatic acute-phase proteins. SL-LPS pretreatment remarkably enhanced the LPS-induced production of IL-6 but did not alter the IL-1β and CRP levels for 24 hr compared to the control, while L-LPS increased IL-6 but decreased IL-1β and CRP levels (Fig. 6). In addition, the LPS-stimulated production of IL-6, IL-1β, and CRP produced by Hepa-1c1c7 cells were remarkably enhanced in the SL-LPS pretreatment compared to those in the L-LPS group.

Fig. 6.

Effects of LPS pretreatment on the LPS-induced production of cytokines and CRP in Hepa-1c1c7 cells. Hepa-1c1c7 cells were pretreated with LPS 50 pg/mL in fresh complete media once a day for 2 days and new Hepa-1c1c7 cells were pretreated with LPS 50 ng/mL once on only 2nd day. And then both of LPS-pretreated Hepa-1c1c7 cells were cultured in fresh complete media for 24 hr or 48 hr in the presence of LPS 10 μg/mL. These experiments were run in tetraplicate and repeated at least twice. Each value represents the mean ± SE. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01. Significantly different from the value in each positive control. #p < 0.05. Significantly different from the value in each SL-LPS.

DISCUSSION

LPS (> 1~300 ng/mL), a potent inducer of inflammation, rapidly causes robust induction of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators in monocytes/macrophages through the TLR4 pathway (3,4). Endotoxin tolerance, which is induced by pre-exposure of low-dose LPS (> 10 ng/mL in vitro) leads to a refractory state limiting the innate immune response by macrophages to infection or injury via a shift away from a pro-inflammatory response toward an antiinflammatory response to subsequent secondary challenge with high-dose LPS (8). SL-LPS (1~100 pg/mL in vitro) “primes” monocytes/macrophages for a more robust response and leads to increased mortality to a secondary LPS challenge, a phenomenon known as the “Shwartzman reaction”, which is characterized by platelet aggregation, vascular occlusion, inhibition of fibrinolysis, neutrophil accumulation, endothelial injury, and variable degrees of apoptosis and necrosis in the microvasculature (2,7,9). One study showed that the endotoxin priming response to SL-LPS resulted in the augmented expression of in vitro pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, although SL-LPS failed to activate nuclear factor-κB (20). SL-LPS has been reported to promote the expression of pro-inflammatory mediator genes via a mechanism by which transcriptional suppressors are removed (10). This evidence suggests that LPS induces pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators in monocytes/macrophages, endotoxin tolerance exhibits a shift away from a pro-inflammatory response toward an anti-inflammatory response to secondary challenge with LPS, and SL-LPS may promote a shift toward more of a proinflammatory response through suppression of the anti-inflammatory response.

In the present study, we found that repeated pre-exposure to 50 ng/mL LPS (L-LPS) or 50 pg/mL LPS (SL-LPS) in the absence of subsequent challenge with high-dose LPS enhanced the production of both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 in RAW 264.7 cells in a dose-dependent manner. These results indicate that pre-exposure to endotoxin may enhance endotoxin-induced signaling cascades that elicit many pro- and anti-inflammatory pathways in a dose-dependent manner. However, in the presence of high-dose LPS, SL-LPS pretreatment significantly enhanced the LPS-induced production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 but not IL-1β in RAW 264.7 cells compared to the control, while L-LPS increased only IL-6 but not TNF-α. These data may support recent evidence showing that pretreatment of L-LPS can induce a hyporesponsive state to subsequent secondary challenge with high-dose LPS in innate immune cells, while SL-LPS results in more robust expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (9). The TNF-α/IL-10 ratio also contributes to the balance of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses. IL-10, which is known as an anti-inflammatory cytokine induced by macrophages in sepsis (21), is dispensable for the development of endotoxin tolerance, but neutralization of IL-10 during the first LPS stimulation induced non-tolerant TNF-α production in response to a secondary endotoxin challenge (22). Our results showed that the TNF-α/IL-10 ratios in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells in the control, SL-LPS, and L-LPS groups were 0.90, 1.00, and 0.89, respectively. These data indicate that SL-LPS pretreatment may be characterized by endotoxin priming in the innate immune system, while L-LPS is characterized by endotoxin tolerance.

PGE2 mediates the stimulatory effects of LPS in the innate immune system, which is associated with regulation of immune responses and induction of inflammatory responses (23). In the present study, repeated pre-exposure of L-LPS strongly enhanced the production of PGE2 by RAW 264.7 cells even without secondary LPS exposure in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, the results obtained from the L-LPS pretreatment support a previous report showing that endotoxin tolerance leads to the suppressed expression of COX2 and production of eicosanoids such as PGE2 (24). Herein, SL-LPS pretreatment remarkably enhanced the LPS-induced production of PGE2 by RAW 264.7 cells compared to the control. These observations indicate that endotoxin tolerance may fail to induce the production of PGE2 by macrophages to the subsequent secondary challenge with high-dose LPS, while endotoxin priming greatly enhanced PGE2 production.

Endotoxin can initiate systemic and local inflammation, bidirectionally leading to reactive oxygen species production, which can induce tissue damage or interfere with normal metabolism in cells (25,26). The results of the present study demonstrated that repeated pretreatment of low-dose LPS remarkably enhanced the production of NO by RAW 264.7 cells without secondary LPS exposure in a dose-dependent manner. The LPS-induced production of NO by RAW 264.7 cells was remarkably enhanced in the SL-LPS and L-LPS groups compared to the control, with no difference between the SL-LPS and L-LPS groups. These observations suggest that both endotoxin priming and endotoxin tolerance may exhibit NO-dependent effects, including oxidative stress and inflammation.

LPS is a potent T-independent antigen promoting humoral immune responses, suggesting that LPS can lead to the downregulation of cell-mediated immunity with a shift in the Th1/Th2 balance toward Th2 and allergic inflammation (27). Endotoxin tolerance also induces suppression of the T-cell mediated immune response (28). Endotoxin tolerance resulted in the reduced production of IL-2 and IFN-γ and the increased production of IL-4 and IL-6 (12,29), indicating that endotoxin tolerance may attenuate cellmediated immunity with a shift in the Th1/Th2 balance toward Th2. Con A is a selective T cell mitogen relative to its effects on B cells. Herein, Con A-induced productivity of IFN-γ by EL4 cells was strongly increased in the control, SL-LPS, and L-LPS pretreatment, while Con A-induced productivity of IL-10 increased in the control and L-LPS groups but was attenuated in the SL-LPS group. In other words, IFN-γ/IL-10 ratios in Con A-stimulated EL4 cells were enhanced in the SL-LPS group compared to the control, while they were attenuated in the L-LPS group. Therefore, these data indicate that L-LPS pretreatment may exhibit a shift in the Th1/Th2 balance toward Th2 by T cell mitogen-stimulated T lymphocytes, while SL-LPS induces a shift in the Th1/Th2 balance toward Th1.

Endotoxin tolerance is associated with profound impairment in the ability to produce the IFN-γ in response to endotoxin (12). Endotoxin tolerance-induced immunosuppression in the innate immune system is clinically observed in sepsis patients, leading to pathologic alteration and mortality (6). However, the immunoparalysis in sepsis has been reported to be partially restored by therapy with recombinant IFN-γ (14), indicating that suppression of the IFN-γ-mediated immune response may also contribute to the immunoparalysis and mortality in sepsis. IL-10 upregulation was also reported to be correlated with higher mortality in patients with sepsis (30). In contrast, elevation of endogenous IFN-γ increased mortality, whereas anti-IFN-γ induced a protective effect from endotoxic shock (13). Collectively, these findings suggest that IFN-γ may play a significant indirect role as an activator of macrophages on the excessive inflammatory response to secondary infection. Interestingly, our results demonstrated that the LPS-stimulated production of IFN-γ but not IL-10 by EL4 cells was strongly downregulated in the SL-LPS and L-LPS groups compared to the control. In other words, IFN-γ/IL-10 ratios in LPS-stimulated EL4 cells in the control, SL-LPS, and L-LPS were 5.83, 1.04, and 0.40, respectively, which were 2.6-fold higher in the SL-LPS group than in the L-LPS group. These data indicate that pretreatments of SL-LPS and L-LPS may contribute to the downregulation of cell-mediated immunity with a shift in the Th1/Th2 balance toward Th2 such as allergic inflammation to subsequent LPS challenge. At the same time, SL-LPS pretreatment may contribute to the induction of a greater Th1-mediated proinflammatory response compared to L-LPS, consequently leading to a proinflammatory response in innate immune cells. However, further studies are needed to reveal the precise mechanism of the role of IFN-γ in the effects of SL-LPS and L-LPS.

The liver, which is a metabolic and immunologic organ, can rapidly activate immunity and promote the production of acute-phase proteins in response to infections or tissue damage, leading to systemic inflammation (31,32). The LPS-induced production of acute-phase proteins by hepatocytes contributes to systemic inflammation and exacerbates the accumulation of oxidative damage products in the liver (33–35). Preconditioning by L-LPS prevented subsequent LPS-induced severe liver injury via Nrf2 activation in mice (36). Acute-phase proteins, including IL-6, IL-1β, and CRP, are well-known markers of inflammation and potent predictors of future metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease (37,38). IL-6 and IL-1β are considered to be strong inducers of CRP in the liver (39). IL-6 and CRP also mediate the development of hepatic insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes (40). However, the effects of pretreatment of SL-LPS and L-LPS on LPS-induced production of acute-phase proteins have been poorly understood to date. The present study indicates that SL-LPS pretreatment may deteriorate hepatic inflammation and the acute-phase response to secondary infection via enhanced production of IL-6, while the L72 B.S. Chae LPS decline partly occurs by the attenuated production of IL-1β and CRP, despite elevated IL-6 levels. In addition, induction of metabolic inflammation and acute-phase responses to secondary endotoxin may be dependent on the preconditioning of low-grade endotoxemia with SL-LPS rather than L-LPS.

In conclusion, these findings suggest that pre-conditioning of SL-LPS may contribute to the mortality to secondary infection in sepsis rather than the pre-conditioning of L-LPS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander C, Rietschel ET. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides and innate immunity. J Endotoxin Res. 2001;7:167–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel PN, Shah RY, Ferguson JF, Reilly MP. Human experimental endotoxemia in modeling the pathophysiology, genomics, and therapeutics of innate immunity in complex cardiometabolic diseases. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:525–534. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Offenbacher S, Salvi GE. Induction of prostaglandin release from macrophages by bacterial endotoxin. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:505–513. doi: 10.1086/515177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawai T, Akira S. Signaling to NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptors. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:460–469. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biswas SK, Lopez-Collazo E. Endotoxin tolerance: new mechanisms, molecules and clinical significance. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:475–487. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng SC, Scicluna BP, Arts RJ, Gresnigt MS, Lachmandas E, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Kox M, Manjeri GR, Wagenaars JA, Cremer OL, Leentjens J, van der Meer AJ, van de Veerdonk FL, Bonten MJ, Schultz MJ, Willems PH, Pickkers P, Joosten LA, van der Poll T, Netea MG. Broad defects in the energy metabolism of leukocytes underlie immunoparalysis in sepsis. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:406–413. doi: 10.1038/ni.3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng H, Maitra U, Morris M, Li L. Molecular mechanism responsible for the priming of macrophage activation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:3897–3906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.424390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen K, Geng S, Yuan R, Diao N, Upchurch Z, Li L. Super-low dose endotoxin pre-conditioning exacerbates sepsis mortality. EBio Medicine. 2015;2:324–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris M, Li L. Molecular mechanisms and pathological consequences of endotoxin tolerance and priming. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2012;60:13–18. doi: 10.1007/s00005-011-0155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maitra U, Gan L, Chang S, Li L. Low-dose endotoxin induces inflammation by selectively removing nuclear receptors and activating CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein δ. J Immunol. 2011;186:4467–4473. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romagnani S. T-cell subsets (Th1 versus Th2) Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:9–18. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62426-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balkhy HH, Heinzel FP. Endotoxin fails to induce IFN-gamma in endotoxin-tolerant mice: deficiencies in both IL-12 heterodimer production and IL-12 responsiveness. J Immunol. 1999;162:3633–3638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinzel FP. The role of IFN-gamma in the pathology of experimental endotoxemia. J Immunol. 1990;145:2920–2924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kox WJ, Volk T, Kox SN, Volk HD. Immunomodulatory therapies in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:S124–S128. doi: 10.1007/s001340051129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boutagy NE, McMillan RP, Frisard MI, Hulver MW. Metabolic endotoxemia with obesity: is it real and is it relevant? Biochimie. 2016;124:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hietbrink F, Besselink MG, Renooij W, de Smet MB, Draisma A, van der Hoeven H, Pickkers P. Systemic inflammation increases intestinal permeability during experimental human endotoxemia. Shock. 2009;32:374–378. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181a2bcd6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Tuohy KM, Chabo C. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarasenko TN, McGuire PJ. The liver is a metabolic and immunologic organ: a reconsideration of metabolic decompensation due to infection in inborn errors of metabolism (IEM) Mol Genet Metab. 2017;121:283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhainaut JF, Marin N, Mignon A, Vinsonneau C. Hepatic response to sepsis: interaction between coagulation and inflammatory processes. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:S42–S47. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maitra U, Gan L, Chang S, Li L. Low-dose endotoxin induces inflammation by selectively removing nuclear receptors and activating CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein δ. J Immunol. 2011;186:4467–4473. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aggarwal NR, Tsushima K, Eto Y, Tripathi A, Mandke P, Mock JR, Garibaldi BT, Singer BD, Sidhaye VK, Horton MR, King LS, D’Alessio FR. Immunological priming requires regulatory T cells and IL-10-producing macrophages to accelerate resolution from severe lung inflammation. J Immunol. 2014;192:4453–4464. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou F, Ciric B, Li H, Yan Y, Li K, Cullimore M, Lauretti E, Gonnella P, Zhang GX, Rostami A. IL-10 deficiency blocks the ability of LPS to regulate expression of tolerance-related molecules on dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1449–1458. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalinski P. Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2. J Immunol. 2012;188:21–28. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernando LP, Fernando AN, Ferlito M, Halushka PV, Cook JA. Suppression of Cox-2 and TNF-alpha mRNA in endotoxin tolerance: effect of cycloheximide, antinomycin D, and okadaic acid. Shock. 2000;14:128–133. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ando K, Fujita T. Metabolic syndrome and oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar S, Adhikari A. Dose-dependent immunomodulating effects of endotoxin in allergic airway inflammation. Innate Immun. 2017;23:249–257. doi: 10.1177/1753425917690443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsushita H, Ohta S, Shiraishi H, Suzuki S, Arima K, Toda S, Tanaka H, Nagai H, Kimoto M, Inokuchi A, Izuhara K. Endotoxin tolerance attenuates airway allergic inflammation in model mice by suppression of the T-cell stimulatory effect of dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2010;22:739–747. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chae BS. Comparative study of the endotoxemia and endotoxin tolerance on the production of Th cytokines and macrophage interleukin-6: differential regulation of indomethacin. Arch Pharm Res. 2002;25:910–916. doi: 10.1007/BF02977013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poujol F, Monneret G, Gallet-Gorius E, Pachot A, Textoris J, Venet F. Ex vivo Stimulation of Lymphocytes with IL-10 mimics sepsis-induced intrinsic T-cell alterations. Immunol Invest. 2017;28:1–15. doi: 10.1080/08820139.2017.1407786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heymann F, Tacke F. Immunology in the liver--from homeostasis to disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:88–110. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bauer M, Press AT, Trauner M. The liver in sepsis: patterns of response and injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2013;19:123–127. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32835eba6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saad B, Frei K, Scholl FA, Fontana A, Maier P. Hepatocyte-derived interleukin-6 and tumor-necrosis factor alpha mediate the lipopolysaccharide-induced acute-phase response and nitric oxide release by cultured rat hepatocytes. Eur J Biochem. 1995;229:349–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.0349k.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panesar N, Tolman K, Mazuski JE. Endotoxin stimulates hepatocyte interleukin-6 production. J Surg Res. 1999;85:251–258. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1999.5648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohamed J, Nazratun Nafizah AH, Zariyantey AH, Budin SB. Mechanisms of diabetes-induced liver damage: the role of oxidative stress and inflammation. J Sultan Qaboos Univ Med. 2016;16:e132–e141. doi: 10.18295/squmj.2016.16.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakasone M, Nakaso K, Horikoshi Y, Hanaki T, Kitagawa Y, Takahashi T, Inagaki Y, Matsura T. Preconditioning by low dose LPS prevents subsequent LPS-induced severe liver injury via Nrf2 activation in mice. Yonago Acta Med. 2016;59:223–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dupuy AM, Terrier N, Sénécal L, Morena M, Leray H, Canaud B, Cristol JP. Is C-reactive protein a marker of inflammation? Nephrologie. 2003;24:337–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ridker PM, Morrow DA. C-reactive protein, inflammation, and coronary risk. Cardiol Clin. 2003;21:315–325. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8651(03)00079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kramer F, Torzewski J, Kamenz J, Veit K, Hombach V, Dedio J, Ivashchenko Y. Interleukin-1beta stimulates acute phase response and C-reactive protein synthesis by inducing an NFkappaB- and C/EBPbeta-dependent autocrine interleukin-6 loop. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:2678–2689. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286:327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]