Significance

Eukaryotic cells use microtubule (MT)-based transport to control the distribution of cargos across their complex and crowded environment. Prior models of MT-based motility considered cargo behavior on single filaments or simple networks. However, numerous recent reports revealed surprisingly complex 3D MT networks and associated complex cargo motility in cells. Such phenomena could not be modeled in previous studies. We show (via a recently developed experimental approach and in silico modeling) that network geometry plays a significant role in MT-based motility: The 3D properties of a single intersection can determine cargo routing, depending on cargo properties (e.g., size), opening the possibility that tuning 3D network geometry allows for selective targeting of cargos around the cell.

Keywords: cytoskeletal transport, biophysics, kinesin, network, microtubules

Abstract

The eukaryotic cell’s microtubule cytoskeleton is a complex 3D filament network. Microtubules cross at a wide variety of separation distances and angles. Prior studies in vivo and in vitro suggest that cargo transport is affected by intersection geometry. However, geometric complexity is not yet widely appreciated as a regulatory factor in its own right, and mechanisms that underlie this mode of regulation are not well understood. We have used our recently reported 3D microtubule manipulation system to build filament crossings de novo in a purified in vitro environment and used them to assay kinesin-1–driven model cargo navigation. We found that 3D microtubule network geometry indeed significantly influences cargo routing, and in particular that it is possible to bias a cargo to pass or switch just by changing either filament spacing or angle. Furthermore, we captured our experimental results in a model which accounts for full 3D geometry, stochastic motion of the cargo and associated motors, as well as motor force production and force-dependent behavior. We used a combination of experimental and theoretical analysis to establish the detailed mechanisms underlying cargo navigation at microtubule crossings.

The microtubule (MT) network in eukaryotic cells is typically a dense, highly variable, 3D mesh. MT network topologies are known to vary widely between cells (1) and even between cells of the same type and lineage (2). Within a network, MTs converge to form crossings at a variety of filament separations and angles of intersection (3). Often, the crossings feature interfilament separations that are comparable to the scale of cargos found within the cell. At these “intersections,” a cargo, with multiple motors on its surface, can interact with several MTs simultaneously. This scenario belongs to a class of tug-of-war (ToW) processes (4, 5), although ToW events between dissimilar motors have received by far the most attention to date. As the result of a ToW, the cargo can pass along the original MT, switch to the crossing filament, pause, or detach. The probabilities of these outcomes are known to be sensitive to the 3D layout of the filaments (6–8), but the mechanisms of this phenomenon are unclear. Given that the architecture/topology of the MT cytoskeleton serves as a backdrop for cargo transport (9), its role in cargo routing warrants investigation.

The importance of MT cytoskeletal architecture is underscored by the fact that MT network remodeling occurs in various diseases and during normal cellular processes. For example, neuritic dearborization or restructuring is encountered in neurodegenerative diseases (10, 11). MT remodeling is also observed in neoplasias (12) and is associated with pathways disturbed in cancers (13). There is also evidence that the geometry of the MT network acts as a regulator to tune insulin granule secretion in mouse pancreatic β-cells (14, 15).

The cell can use multiple mechanisms to modulate its MT architecture. MTs can be locked in parallel (16) or antiparallel (17) via cross-linking. Axonal branching shows a preference for normal angles (18); low branch angles can arise from MT nucleating factors (19). The cell can set overall MT spacing by controlling the amount of polymerized tubulin, either via regulation of expression levels (20) or filament stability (21). Filament spacing can also be controlled via MT-associated proteins that cross-link MTs (22). MT and actin networks are often coupled, and remodeling of one can drive structural changes in the other (23, 24). External factors which affect cell shape can also regulate MT network topology (25). Finally, MT crossings are known to be special loci for network regulation (26). Currently, the implications of these topology variations for cargo logistics and overall biomechanics are not quantitatively understood.

Decoupling the influence of the MT network’s 3D topology from regulatory protein factors is challenging. The same pathways that drive network remodeling can also couple to motor regulation. As a result, the impact of geometric changes in MT networks on intracellular cargo transport has been difficult to isolate and quantitate. It is common in biology to think in terms of chemical regulation. However, to understand how intracellular cargo transport functions, it is critical to gain a baseline understanding of how 3D MT geometry impacts cargo distribution, starting at the most fundamental level of the MT network: individual MT–MT intersections.

Studying cargo navigational behavior as a function of 3D network geometry poses considerable experimental challenges. In vivo investigations cannot easily decouple chemical and topological regulation, as discussed above. Moreover, although theoretical work highlights its importance (8), in vitro bead assays that use traditional MT–glass deposition techniques are also unable to model MT–MT crossings with controlled filament separation (7, 27). Recently, Lombardo et al. (28) developed a technique to examine how cargos driven by myosin V motors navigate 3D intersections of actin filaments. Their approach is a major advance. However, no existing technique has been shown to allow for all geometric factors (as well as filament tension) to be dynamically adjustable in situ or for multiple intersections to be built in a controlled scalable fashion.

To address this experimental need and the question of cargo navigation on MTs, we developed a scalable in vitro system to suspend and dynamically manipulate multiple individual MT filaments in 3D. Each MT was manipulated individually via holographic optical trapping of two or more bead handles, as described (29). We used this bottom-up approach to systematically construct MT–MT intersections featuring various angles and separations. We then measured the statistics of kinesin-1–driven cargo transport on these MT geometries and used these data to constrain 3D simulations. We show from experimental data and theoretical analysis that navigational outcomes exhibit systematic variation based on 3D MT intersection geometry. Furthermore, we propose dynamic mechanisms that explain the observed preferences.

Results

Experimental Setup.

The broad aim of this work was to understand the impact of cytoskeletal geometry on intracellular transport. A comprehensive experimental model of all possible geometries is beyond the scope of any one study, so we restricted our scope to representative scenarios. We focused on the simplest MT intersections—where just two filaments cross (Fig. 1A). We used 1-µm-diameter silica microspheres, driven by full-length kinesin heavy-chain (KIF5A) homodimers, as our cargos. This is a common, albeit simplified, model for in vitro work. We focused on assays outside the single-motor regime because there is substantial evidence that cargos in cells are often driven by multiple motor ensembles, and indeed multiple-motor ensembles are essential for a ToW to develop.

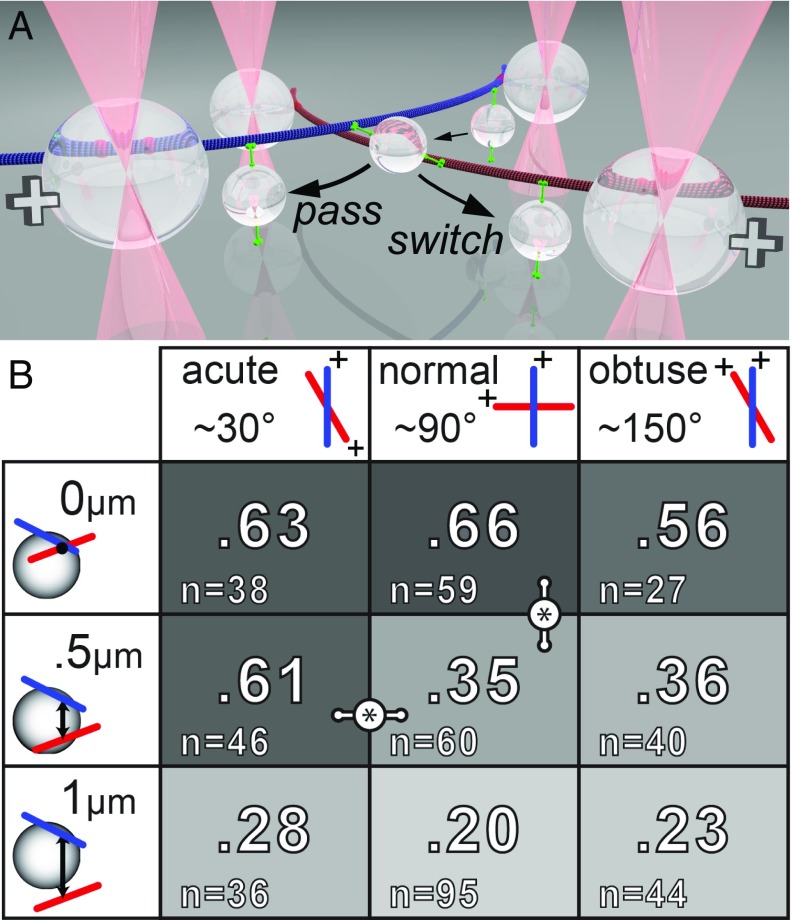

Fig. 1.

The 3D MT crossings and cargo navigational outcomes. (A) Illustration of in vitro 3D MT crossing with a cargo undergoing ToW and its possible outcomes. Bead handles (large spheres) are permanently bound to MTs (blue and red). They are held in 3D via holographically defined optical traps (light pink cones). MT plus ends are indicated (+). For clarity, we only depict two motors on the cargo (small bead), engaged on either MT. Navigational outcomes consist of the cargo moving on either MT toward the plus end (both cases shown), and the switch/pass classification of each outcome is indicated with labeled arrows. (B) Switching probabilities as a function of 3D MT arrangement. Higher switch rates are highlighted by a darker background. Significant differences (P < 0.05, Barnard’s test) are indicated by links.

In vitro, we manipulated MTs in 3D via holographically defined optical traps (29) to construct intersections with three filament spacings: zero, radius, and diameter of the cargo (0, 0.5, and 1 µm). We only parameterized this range because the probability of a cargo interacting with both MTs for separations greater than the cargo diameter quickly becomes negligible. For each separation distance, we examined three angles of intersection: acute (∼30°; MT polarities nearly counteraligned), normal (90°), and obtuse (∼150°; MT polarities nearly aligned), for a total of nine geometric conditions (Fig. 1B). We estimated angular precision to be ±1.7°.

We deposited the bead onto the upper “primary” MT. The silica microspheres used as our cargos have a density approximately two times that of water, which biased them to hang down. This made them likely to encounter the lower “crossing” MT (Fig. 1A), although Brownian motion along all three axes was observed. Thus, our 0-µm separation experiments resembled the “underpass” MT geometry in prior experiments, in which MTs were attached to a glass substrate (7, 27). However, our experimental model allowed for MT bending, twisting, and vibrations, which cannot be fully recapitulated when MTs are firmly attached to a solid substrate. The absence of the glass substrate in our work was a major difference since the cargo could explore many more 3D paths as it negotiated the intersection.

Final Navigational Outcomes Depend on 3D Geometry.

For each of the nine MT network arrangements, we quantified final cargo routing outcomes strictly in terms of “switching” or “passing” because detachment at intersections was negligible (∼2% of events). We do not report pause events, because we characterized the entire navigational event, even in cases where the cargo’s navigational choice took several seconds.

Our results suggest that 3D MT network topology can be an effective regulator of cargo routing (Fig. 1B) independent of other regulatory influences (chemical and biophysical). Geometries in the upper left corner of the table promoted switching, while those in the lower right corner promoted passing. The fact that certain geometries could promote switching was particularly unexpected, since it was not reported by Lombardo et al. (28) for the actin–myosin liposome system. One difference may be that the liposome system allowed motors to diffuse along the surface of the cargo, whereas our bead system did not. Our result for normal intersections and zero separations was in approximate agreement with the work of Ross et al. (7), where switching probability for underpass geometries on a glass slide was ∼70%.

Routing outcomes are determined by multiple geometric factors interacting in nontrivial ways. Disentangling these factors by intuition alone is challenging; therefore, we relied on in silico modeling. Many fine mechanistic details were resolved by our experimental approach (see below), which constrained the in silico model.

Characterization of ToW Events.

ToW is necessary for switching; therefore, we first characterized ToW occurrence and duration. The ToW was identified by looking at several parameters: motility track, motion of intersecting MTs, and force on bead handles. Any one parameter of the three was allowed to be ambiguous. Our spatiotemporal resolution was sufficient to establish whether a ToW took place and to precisely determine ToW durations.

We identified ToW start and end by observing cargo displacements away from MT axes and associated deflections (Fig. 2A). Bead tracks for representative pass (Fig. 2B) and switch (Fig. 2C) events (Movies S1 and S2) are shown, along with their displacements projected along the axes of the intersecting MTs. A ToW start was identified with the beginning of a sustained displacement on the crossing MT’s axis. The ToW end was identified when the cargo snapped back upon dissociation from either the primary or crossing MT. Bead handle displacements can also be used as an indicator of a ToW (Figs. 1B and 2 A, Middle, and D). A slowdown in cargo movement along the primary MT (Fig. 2 B and C) was also often observed.

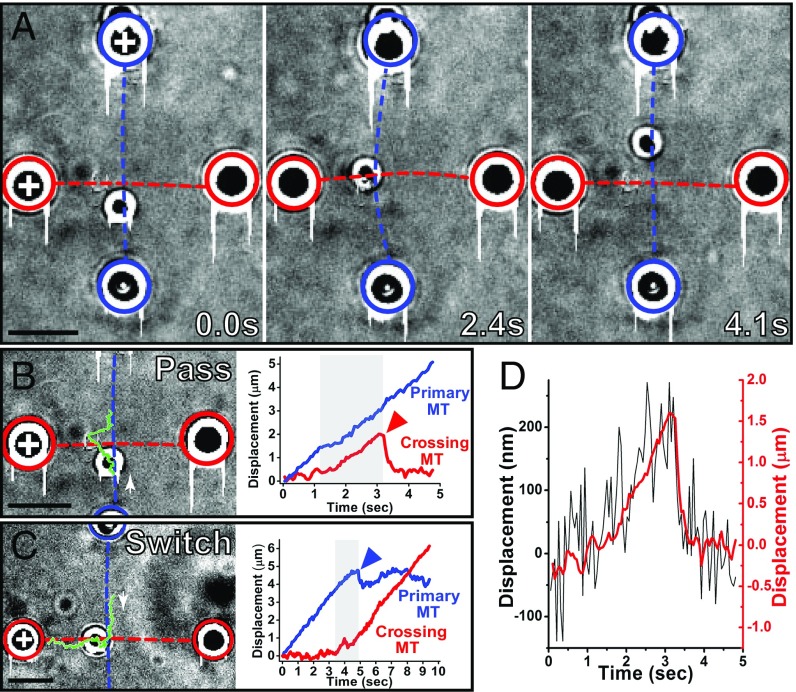

Fig. 2.

Identification and quantification of ToW. (A) Three movie frames: before (Left), during (Center), and after (Right) ToW. +, MT plus ends. Note the displacement of the top bead handle during ToW. Frame timings are shown in the lower right corner of each image. (B) Analysis of the pass event shown in A. (B, Left) Trajectory of the cargo (green) overlaid on one cropped movie frame. White arrow, the start of the track and the plus-end direction on the primary MT. (B, Right) Cargo displacements projected along the primary (blue) and crossing (red) MT directions. Red arrowhead, the snapback event which is typical of a ToW conclusion; gray band, ToW temporal extent (∼1.9 s). (C) Analysis of a switch event. (C, Left) Trajectory of the cargo (green) overlaid on one movie frame. White arrow, the start of the track and the plus-end direction on the primary MT. (C, Right) Cargo displacement projected along the primary (blue) and crossing (red) MT’s axes (0.5-μm separation). Blue arrowhead, the snapback event which is typical of a ToW conclusion; gray band, ToW temporal extent (∼1.6 s). Common highlight scheme for A–C: Blue/red dashed lines and circles, primary/crossing MT positions and bead handle positions (0.5-μm separation geometry). (D) Cargo displacement (red) along the crossing MT axis shown in B overlaid onto trace of bead handle displacement (black) from trap center, due to ToW (for the top bead handle in A). (Scale bars, 5 µm.)

Bead handle displacements were also an indicator of how many motors were exerting force on the bead. We set the trap stiffness at ∼1 pN per 100 nm, so that a single kinesin motor could not pull the bead handle out of the trap (escape event), but two or more motors working together could (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Quantifying collective activity of multiple motors via trap escape forces is a well-established approach both in vivo (30, 31) and in vitro (32) and has been validated in silico (32). We controlled the surface density of motors on cargos by discarding assays in which bead handle escape fraction was >25% of total events. This provided refined control on top of the more coarse approach of controlling motor concentration at incubation time. It also provided confidence that ToWs in our assays were dominated by forces from one to two kinesin motors; more motors were likely engaged on the MT, but not all were positioned to exert force during the ToW.

Mechanisms of Cargo Routing.

The ability to sensitively detect ToW events allowed us to quantify their probability. Our data indicated that ToW probability is sensitive to 3D geometry: It was higher for narrower filament separations and for acute/obtuse angles (Table 1). For 0-µm separations, ToW probability was so high that significant differences as a function of angle may not be practical to measure. A different pattern of navigational outcomes emerged when no-ToW events were omitted. Therefore, we also examined the probability for the cargo to pass or switch, conditional on ToW occurrence (Table 2 vs. Fig. 1C). Four of nine geometries showed switch probabilities close to 50%. Switch probabilities were significantly higher than 50% for the following geometries: 0 µm normal, 0 µm acute, and 0.5 µm acute (P < 0.05, Barnard’s test). We concluded that geometric constraints can promote or inhibit switching outcomes for ToW events.

Table 1.

ToW probabilities as a function of 3D MT geometry

| Angle | |||

| Separation | Acute | Normal | Obtuse |

| 0 μm | 0.79 (n = 38) | 0.93 (n = 59) | 0.89 (n = 27) |

| 0.5 μm | 0.83 (n = 46) | 0.70 (n = 60) | 0.80 (n = 40) |

| 1 μm | 0.58 (n = 36) | 0.46 (n = 95) | 0.64 (n = 44) |

The distance between MTs (rows) and intersection angle (columns) provide full geometric specification for a MT intersection. The angles and distances are as visually illustrated in Fig. 1B. In each case, the number of measurements is given in parentheses. See Fig. 3B for comparison with modeling results.

Table 2.

Probabilities of a switching outcome conditional on a ToW taking place, as a function of 3D MT network geometry

| Angle | |||

| Separation | Acute | Normal | Obtuse |

| 0 μm | 0.80* (n = 30) | 0.71* (n = 55) | 0.63 (n = 24) |

| 0.5 μm | 0.74* (n = 38) | 0.50 (n = 42) | 0.47 (n = 32) |

| 1 μm | 0.48 (n = 21) | 0.44 (n = 44) | 0.36 (n = 28) |

The distance between MTs (rows) and intersection angle (columns) provide full geometric specification for a MT intersection. The angles and distances are as visually illustrated in Fig. 1B. In each case, the number of measurements is given in parentheses. See Fig. 3C for comparison with modeling results. *P < 0.05 (Barnard’s test).

A Mathematical Model of Cargo Transport Reproduces Observed Switch Probabilities.

It is difficult to disentangle the mechanism through which each factor acts (in concert) to determine ToW and switching probabilities. Therefore, we constructed an in silico model of cargo transport. This model allowed us to examine experimentally unobservable details, such as how motor locations, bound states, and force states changed with time.

We modeled the cargo as a 3D solid sphere which underwent translational and rotational diffusion. Attached to the cargo were a number of motors, which may bind to MTs within reach and step and unbind from the MT with rates dependent on the force experienced by spring-like motor stalks (Fig. 3A). We derived the equations of motion of the cargo from force balance and simulated stochastic trajectories. Simulated MTs did not move, twist, or bend. The 500 cargo trajectories were simulated independently for each assay geometry, and probabilities of ToW and switching were determined analogously to the experimental data (Movies S3–S10). For full simulation details and parameter fitting procedure, see SI Appendix, sections 1 and 2. Briefly, two parameters could not be established from current experiments or prior literature: the number of motors on the cargo and motor on-rate. These two parameters were constrained by matching three experimental observations: ToW probability as a function of geometry (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), fraction of bead handle escape events, and cargo run lengths (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Thus, the model was fully constrained and therefore predictive.

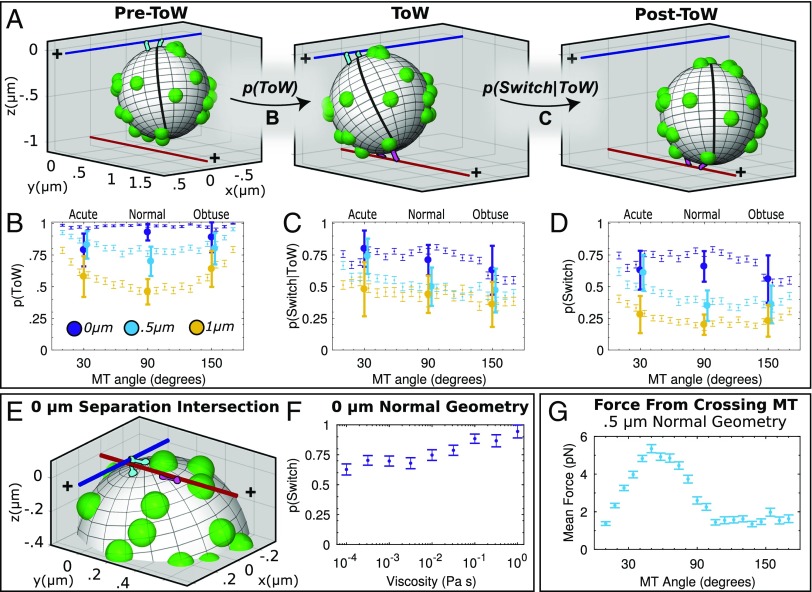

Fig. 3.

Mathematical model of navigational outcomes. (A) Snapshots of simulated cargo activity at an intersection (color coding as in Fig. 1B). Examples of Pre-ToW (A, Left), ToW (A, Center), and post-ToW (A, Right) states are shown. Motors bound to the primary MT are shown in cyan. Motors bound to the crossing MT are shown in magenta. Unbound motors are shown as green spherical protrusions from the cargo; sphere radius represents motor’s maximal reach. Bead’s prime meridian is demarcated to emphasize rotational movement. (B) Simulated probabilities to engage in ToW. Probability of undergoing ToW for each geometry is shown as thin symbols (error bars: SEM). Experimental data (Table 1) are shown as large symbols (error bars: 95% C.I.). Experimental data points for 0.5-μm geometries are shifted slightly horizontally to aid the eye. (C) Simulated probability to switch, given the cargo engaged in ToW. Simulated and experimental data (Table 2) represented as in B. (D) Simulated probability to switch, overall, i.e., the product of probability to ToW (B) and probability to switch, given ToW (C). Simulated and experimental data (Fig. 1B) are represented as in B. (E) Snapshot of a ToW for 0 μm, 90° geometry. Here, primary MT motors are blocked from passing the intersection by the crossing MT at 0 μm. Bound and unbound motors represented as in A. (F) Probability to switch increases with increasing simulated fluid viscosity. Error bars: SEM. Curve represents a linear fit. (G) Force exerted by crossing MT on the cargo for 0.5-μm geometries (mean ± SEM).

We found good agreement between experimentally observed and theoretically predicted probabilities of ToW and switching (Fig. 3 B–D). We therefore used this simulation to investigate the mechanisms of cargo navigation at MT intersections.

The Influence of Intersection Geometry on ToW Probability.

The longer a cargo spends within reach of the primary and crossing MTs (henceforth, the ToW zone), the more chances unbound motors on the cargo have to engage the crossing MT. This phenomenon can be understood from a simple, heuristic model. If we assume the cargo has a single rate of binding to the crossing MT, given by , the probability the cargo binds to the crossing MT before leaving the ToW zone is

where v is the cargo velocity and dToW is the length of the ToW zone. This simple model reproduces experimental ToW probabilities for both the 0.5- and 1-μm separation distance geometries (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), but not for the 0-µm separation geometries, suggesting that there were mechanisms at play for 0-μm separations which were not present at other distances (see below).

On the other hand, our full model closely recapitulated all experimental ToW probabilities, including 0-μm separation data. The model captured several a priori intuitive features of the system. For 0-μm geometries, there was guaranteed to be a pool of motors able to bind the crossing MT (namely, the already engaged motors). Thus, we expected the ToW probability for all angles to be close to 1, which our model reproduced. For 0.5- and 1-μm geometries, we expected higher ToW probability for longer ToW zones (acute and obtuse angles). Indeed, simulated ToW probabilities were smallest for 90° intersections (Fig. 3B). Also, as expected, they were symmetric about the normal angle (since kinesin binding is not affected by MT polarity). Simulated ToW probabilities also increased when MT separation decreased from 1 to 0.5 µm, as expected. When the crossing MT encountered the cargo’s midsection, at 0.5-µm separations, it sampled more of the bead’s surface area as it attempted to pass. Hence, at 0.5-µm separation, more motors encountered the crossing MT, increasing ToW probability.

The Influence of Intersection Geometry on Navigational Outcomes, Given ToW.

Experimentally, we observed a large range of geometries (most 0.5- and 1-µm geometries) where the conditional probability to switch was ∼50%. At first glance, this appears intuitive: If ToW lasts ∼1 s or more (our experimental ToW durations averaged ∼3 s; SI Appendix, Fig. S3), then the motor team engaged on the crossing MT should have been able to reach steady state (33) and become equal in number to the primary motor team. With two equivalent ways to proceed, the probability of either would have been ∼50%. However, such a consideration is too simplistic, as we discuss below.

As in experiment, we identified ToW and probability of switching conditional on ToW in simulation (Fig. 3 A–D). We assessed whether the number of motors in the two ensembles during ToW was in fact equal in our simulations. We found that, contrary to expectation, the number of engaged motors on the crossing MT was slightly but significantly lower than that on the primary MT (ratio of ∼0.7; SI Appendix, Fig. S4). The reason is that the motors already engaged on the primary MT constrained the bead from a full range of linear and rotational diffusion. Once a ToW starts, the bead diffusion is even more constrained; this curtailed the number of motors that could reach the crossing MT. Thus, the primary MT team generally has an advantage. However, the two paths to proceed are not equivalent either. The crossing MT itself can exert a force which hinders the cargo from passing (Fig. 3G). The smooth decrease from passing to switching prevalence across our experimental geometries (Table 2) therefore reflected the balance between net motor activity (which is biased in favor of moving along the primary MT) and steric hindrance from the crossing MT.

The Limits of Geometric Regulation.

Our results establish that a single MT intersection can significantly bias cargo routing toward switching or passing. The former was not reported for the 3D liposome motility system (28). Notably, in our system, the motors were anchored at fixed locations on the bead surface, whereas in the liposome system, they were free to diffuse. Protein anchoring in cells can range from fixed to readily movable, which raises the possibility that factors like membrane fluidity can directly affect cargo routing in cells. These effects are of great interest for future work.

Can a single MT intersection produce a near-100% bias for switching or passing? What are the mechanisms which affect these limits? Approximately 100% passing naturally occurs for intersections with filament separation much greater than cargo diameter. Is 100% switching attainable? To address this, we considered two special cases which lead to elevated probability to switch and their broader implications for geometric regulation. For completeness, we also discuss each experimental geometry individually in SI Appendix, section 3.

Low Filament Separations.

A closer look at the geometric setup (Fig. 3E) makes it clear that the 0-μm case is qualitatively distinct. At 0-μm separation, the crossing MT sterically hindered the motors engaged on the primary MT. To pass, the cargo could “hurdle” over the crossing MT due to Brownian motion, but this was improbable for our large silica beads (density ∼ 2× water). It would also be unlikely in the cytosolic environment, where cargo diffusion is often highly constrained (even for smaller cargos). The only other way for the cargo to pass is by first diffusing underneath the crossing MT, then having unengaged motors on its surface bind to the distal side of the primary MT (Fig. 4A and Movie S8). All other motors must then disengage before the distal ones.

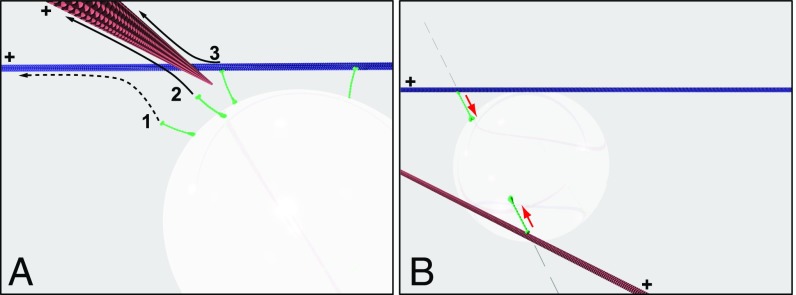

Fig. 4.

Mechanisms that elevate switch probabilities. (A) Illustration of a cargo approaching a normal intersection with a separation of 0 µm. As shown, the cargo is attached to the upper (primary) MT via two motors. The cargo has three options, as labeled: 1, Unengaged motors can bind the primary MT at a site distal to filament intersection (a pass would occur if the proximal motors were to be subsequently released); 2, unengaged motors can bind the crossing MT; or 3, motors engaged on the primary MT can detach, then rebind to the crossing MT. All motors are in green regardless of engagement status. (B) Illustration of a cargo engaged in a ToW at an acute 0.5-µm intersection. A minimal ToW with only two motors is shown for visual clarity. The forces exerted by motors are counteraligned (gray arrows) and serve to “wedge” the cargo between the MTs. Red arrows point to MT plus ends.

This mechanism suggests passing at 0-μm separation should depend on the diffusion properties of the medium. Our simulations demonstrated that, for high viscosities, where cargo diffusion is suppressed, the preference to switch approaches 100% (Fig. 3F and Movie S9).

Acute Angles/Intermediate Separations.

Why is switching more prevalent for 0.5-μm acute geometry? Again, this is likely due to the crossing MT acting as a hindrance, but the mechanism cannot be the same as for low filament separations. Here, the cargo could not pass under the crossing MT, but it could hurdle over it. In this case, for switching probability to be elevated, this latter mechanism must be suppressed. The vertical forces associated with the ToW for 0.5-μm acute geometry pulled the cargo between MTs. This effectively wedged the cargo between them and prevented it from moving above the crossing MT (Fig. 4B and Movie S10). In our simulations, MTs were not allowed to bend. In experiment, the two motor teams in this scenario would have been expected to pull the two MTs closer together, making the crossing MT an even stronger obstacle. This is likely the reason experimentally observed switching probability for 0.5-μm acute geometry was somewhat higher than theoretical prediction.

Discussion

Cargos driven by multiple motors can exhibit incredibly complex behavior. Even when one considers this for a single cargo moving along a single MT, the complexity is sufficient to lead to highly nontrivial emergent behaviors (34, 35). The number of motors in biologically relevant systems is typically small, which necessitates detailed experiments and modeling to account for not only averaged behavior, but also the effect of fluctuations. The addition of just one more filament adds such complexity that the emergent behaviors can dramatically diverge to give rise to discrete outcomes: passing and switching. It is therefore a fascinating model system to study emergent behaviors in biology.

We have modeled this problem in a highly controlled experimental environment in which we imposed specific restrictions on cargo size and other variables. For example, cargos were larger than motor size, and motors could not diffuse along the cargo surface. We then performed modeling of our system in silico to generalize our experimental results. We were thus able to infer the key processes which underlie our observations. This enabled us to extrapolate how cargo routing might function in cells (and other environments).

Our analysis shows that the team of motors driving the cargo along the primary MT is generally at an advantage, even when the ToW is prolonged. This implies that there is an inherent bias to pass. However, our data show that, for many geometric conditions, passing and switching is balanced, and in some cases, switching dominates. The factor which shifts the balance between passing and switching is the extent to which the crossing MT acts to sterically hinder progression along the primary MT.

We show that the crossing MT can be an effective obstacle, especially when it intersects at an acute angle with intermediate or near-zero separation. Both geometries significantly inhibit passing but via different mechanisms: Intermediate separations with acute angles lead to cargos being wedged between the two MTs, while in near-zero filament separations, passing is only accessible via a multistep, and hence unlikely, process. These results imply that the cell could selectively route cargos of different sizes by controlling MT intersection angle and spacing.

Our simulations closely followed the experimental results, but two important deviations were seen: The conditional probability to switch given that ToW already started was higher in experiments than in simulations for some geometries. Also, the time a cargo spent at the intersection was higher in the experiment than in simulation (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). In both cases, we believe this discrepancy stemmed from modeling MTs as infinitely rigid rods. We analyze MT bending in SI Appendix, section 4 and highlight how model results could be changed by MT bending. To date, MT rigidity has been mostly studied separately from MT-based transport. Our work suggests that MT bending, and, more generally, biomechanics of the MT cytoskeleton, must be taken into account in future studies of intracellular motility, as they are a nonnegligible contributor to cargo routing.

A faithful and detailed in silico model of cargo motility and the ToW process enabled us to speculate about cargo navigation patterns beyond our specific conditions. We show that as viscosity increases, switching is more strongly favored for near-zero filament separations. These simulations predict that local microrheology can be a regulator of cargo routing.

Our work opens up a prospect of a comprehensive quantitative understanding of intracellular cargo fluxes from a single-molecule mechanistic perspective.

Materials and Methods

Our holographic optical trapping and bead assays were performed as described (29) with minor changes; see SI Appendix for more details of protocols and calibration. Much of our data are in the form of contingency tables, so Barnard’s exact tests were used to assess significance of differences between outcomes. Superresolution images were recorded with a Vutara commercial microscope (Bruker) based on single-molecule localization biplane FPALM technology (36, 37); see SI Appendix for more experimental details. Numerical simulations were based on a hybrid Euler–Maruyama–Gillespie scheme, written in C; see SI Appendix for a detailed discussion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Erik Jorgensen for helpful discussions and guidance on super-resolution imaging of MTs. This work was supported by NSF Grant ENG-1563280 (to M.D.V.) and NIH Grants T32 EB009418-07 (support for M.J.B.) and R01 GM123068 (to J.F.A. and S.P.G.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: M.V.G. is employed by Bruker Nano Surfaces. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1707936115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Schnorrenberg S, et al. In vivo super-resolution RESOLFT microscopy of Drosophila melanogaster. Elife. 2016;5:e15567. doi: 10.7554/eLife.15567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong B, Yang X, Zhu S, Bassham DC, Fang N. Stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy imaging of microtubule arrays in intact Arabidopsis thaliana seedling roots. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15694. doi: 10.1038/srep15694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang B, Wang W, Bates M, Zhuang X. Three-dimensional super-resolution imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy. Science. 2008;319:810–813. doi: 10.1126/science.1153529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller MJI, Klumpp S, Lipowsky R. Tug-of-war as a cooperative mechanism for bidirectional cargo transport by molecular motors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4609–4614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706825105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osunbayo O, et al. Cargo transport at microtubule crossings: Evidence for prolonged tug-of-war between kinesin motors. Biophys J. 2015;108:1480–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bálint Š, Verdeny Vilanova I, Sandoval Álvarez Á, Lakadamyali M. Correlative live-cell and superresolution microscopy reveals cargo transport dynamics at microtubule intersections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:3375–3380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219206110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross JL, Shuman H, Holzbaur ELF, Goldman YE. Kinesin and dynein-dynactin at intersecting microtubules: Motor density affects dynein function. Biophys J. 2008;94:3115–3125. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.120014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erickson RP, Gross SP, Yu CC. Filament-filament switching can be regulated by separation between filaments together with cargo motor number. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verdeny-Vilanova I, et al. 3D motion of vesicles along microtubules helps them to circumvent obstacles in cells. J Cell Sci. 2017;130:1904–1916. doi: 10.1242/jcs.201178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Battum EY, Brignani S, Pasterkamp RJ. Axon guidance proteins in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:532–546. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70257-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Polo A. Dendrite pathology and neurodegeneration: Focus on mTOR. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10:559–561. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.155421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker AL, Kavallaris M, McCarroll JA. Microtubules and their role in cellular stress in cancer. Front Oncol. 2014;4:153. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galmarini CM, et al. Drug resistance associated with loss of p53 involves extensive alterations in microtubule composition and dynamics. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:1793–1799. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu X, et al. Microtubules negatively regulate insulin secretion in pancreatic β cells. Dev Cell. 2015;34:656–668. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heaslip AT, et al. Cytoskeletal dependence of insulin granule movement dynamics in INS-1 beta-cells in response to glucose. PLoS One. 2014;9:e109082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fink G, et al. The mitotic kinesin-14 Ncd drives directional microtubule-microtubule sliding. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:717–723. doi: 10.1038/ncb1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subramanian R, et al. Insights into antiparallel microtubule crosslinking by PRC1, a conserved nonmotor microtubule binding protein. Cell. 2010;142:433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalil K, Dent EW. Branch management: Mechanisms of axon branching in the developing vertebrate CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:7–18. doi: 10.1038/nrn3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petry S, Groen AC, Ishihara K, Mitchison TJ, Vale RD. Branching microtubule nucleation in Xenopus egg extracts mediated by augmin and TPX2. Cell. 2013;152:768–777. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dumontet C, et al. Differential expression of tubulin isotypes during the cell cycle. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1996;35:49–58. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1996)35:1<49::AID-CM4>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai A, Mitchison TJ. Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:83–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirokawa N, Shiomura Y, Okabe S. Tau proteins: The molecular structure and mode of binding on microtubules. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1449–1459. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chesarone MA, DuPage AG, Goode BL. Unleashing formins to remodel the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:62–74. doi: 10.1038/nrm2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young KG, Thurston SF, Copeland S, Smallwood C, Copeland JW. INF1 is a novel microtubule-associated formin. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5168–5180. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomez JM, Chumakova L, Bulgakova NA, Brown NH. Microtubule organization is determined by the shape of epithelial cells. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13172. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamant O. Cell biology: Cytoskeleton network topology feeds back on its regulation. Curr Biol. 2013;23:R963–R965. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vershinin M, Carter BC, Razafsky DS, King SJ, Gross SP. Multiple-motor based transport and its regulation by Tau. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:87–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607919104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lombardo AT, et al. Myosin Va molecular motors manoeuvre liposome cargo through suspended actin filament intersections in vitro. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15692. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bergman J, Osunbayo O, Vershinin M. Constructing 3D microtubule networks using holographic optical trapping. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18085. doi: 10.1038/srep18085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashkin A, Schütze K, Dziedzic JM, Euteneuer U, Schliwa M. Force generation of organelle transport measured in vivo by an infrared laser trap. Nature. 1990;348:346–348. doi: 10.1038/348346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gross SP, Welte MA, Block SM, Wieschaus EF. Coordination of opposite-polarity microtubule motors. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:715–724. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKenney RJ, Vershinin M, Kunwar A, Vallee RB, Gross SP. LIS1 and NudE induce a persistent dynein force-producing state. Cell. 2010;141:304–314. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erickson RP, Jia Z, Gross SP, Yu CC. How molecular motors are arranged on a cargo is important for vesicular transport. PLOS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunwar A, Vershinin M, Xu J, Gross SP. Stepping, strain gating, and an unexpected force-velocity curve for multiple-motor-based transport. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jamison DK, Driver JW, Rogers AR, Constantinou PE, Diehl MR. Two kinesins transport cargo primarily via the action of one motor: Implications for intracellular transport. Biophys J. 2010;99:2967–2977. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Juette MF, et al. Three-dimensional sub-100 nm resolution fluorescence microscopy of thick samples. Nat Methods. 2008;5:527–529. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mlodzianoski MJ, Juette MF, Beane GL, Bewersdorf J. Experimental characterization of 3D localization techniques for particle-tracking and super-resolution microscopy. Opt Express. 2009;17:8264–8277. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.008264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.