Significance

Precision delivery of cancer drugs to tumor site is crucial for improving therapeutic efficacy and minimizing adverse effects. Despite tremendous efforts, current drug delivery systems remain an unmet clinical need for cancer therapy. Herein, we propose a unique concept of applying external light to control drug delivery in cancer tissues. In preclinical cancer models, we demonstrate that the near-infrared light-induced decomposition of black phosphorus hydrogel accurately releases drugs in tumor tissues to eradicate subcutaneous breast and melanoma cancers without causing any adverse effects. We believe that our therapeutic system can be used for effective treatment of most cancer types. Our findings may likely bring about a paradigm shift in clinical treatment of cancer and millions of cancer patients will benefit from our findings.

Keywords: black phosphorus, drug delivery, NIR-light responsive, hydrogel, cancer therapy

Abstract

A biodegradable drug delivery system (DDS) is one the most promising therapeutic strategies for cancer therapy. Here, we propose a unique concept of light activation of black phosphorus (BP) at hydrogel nanostructures for cancer therapy. A photosensitizer converts light into heat that softens and melts drug-loaded hydrogel-based nanostructures. Drug release rates can be accurately controlled by light intensity, exposure duration, BP concentration, and hydrogel composition. Owing to sufficiently deep penetration of near-infrared (NIR) light through tissues, our BP-based system shows high therapeutic efficacy for treatment of s.c. cancers. Importantly, our drug delivery system is completely harmless and degradable in vivo. Together, our work proposes a unique concept for precision cancer therapy by external light excitation to release cancer drugs. If these findings are successfully translated into the clinic, millions of patients with cancer will benefit from our work.

Cancer is a life-threatening disease worldwide and cancer-related deaths are higher than those caused by AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis combined. About one-fifth of human deaths are caused by cancer (1). Several standard approaches, such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, etc., are clinically approved for cancer therapy; however, these modalities suffer from low therapeutic efficacy, due to the incomplete excision of the solid tumor as well as the remaining circulation tumor cells. Therefore, therapeutic strategies that are convenient for application, with high specificity, high efficacy, and low adverse effects are urgently needed.

Localized therapeutic approaches would be very attractive for cancer treatment, due to the strong targeted features to change the redistribution of drug in vivo, compared with i.v. injection (2). However, this treatment requires frequent injections of chemotherapy drugs. This is a particular problem for cancer treatment as the invasive injection of drugs to the cancerous tissue and organ frequently brings pain to the patients and may lead to many postoperative complications. Consequently, it calls for a shift of researchers’ attentions toward a drug delivery platform that enables sustained and controlled drug release during the treatment cycle (3). Many polymer-based drug delivery systems (DDSs) have been investigated to allow direct targeting of the tumor and the delivering of drugs that can be released during the natural degradation process of the polymers (4, 5). However, the release rate can hardly be controlled, bringing up double consequences. That is, there is no therapy effect due to failing to reach the minimum therapeutic concentration and, even worse, increasing the risk of resistance in cancer cells.

Therefore, there is an urgent need for one-time injection and controlled release of drug for cancer treatment, as an effective therapeutic strategy to improve the treatment effect and reduce patient pain. A delivery nanoplatform that can simultaneously function as a drug depot, enabling sustained release or controlled burst release of therapeutic agents (6–19), would greatly benefit patients and increase the availability of clinical treatments.

A light-responsive hydrogel is an ideal controlled drug delivery platform, due to its minimal invasiveness and potential for controlled release (20). The light-controlled reversible phase transition of the hydrogel can be used to deliver drug repeatedly. Moreover, the release rate can be tuned remotely by several light parameters, such as wavelength, power density, and exposure time, etc. Generally, gold nanoparticles (21–23) and the emerging 2D nanomaterials, such as graphene (24–26) and MXenes (27), and transition-metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), such as molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) (28, 29) and tungsten disulfide (WS2) (30–32), are the frequently used photothermal transducing agents (PTAs), due to their near-infrared (NIR) light response characteristics, ease of fabrication, and tunability in optical properties. However, most of them are subject to serious limitations such as a weak photothermal conversion efficient, relatively low biosafety and biodegradability, difficulty in metabolizing out of the human body, undegradability, and cytotoxicity that remain a practice challenge for clinical applications (33, 34). Therefore, there is a strong motivation to explore novel PTAs with a required comprehensive performance which is of significant importance for clinical application.

Recently, black phosphorus (BP), a newly discovered 2D material, has shown many novel properties, such as a tunable and direct energy band gap (35–41), a high photothermal conversion efficient (42, 43), easy fabrication and relatively high chemical reactivity that may allow for high drug-loading ability and increased loading capacity (11), and excellent biocompatibility and biodegradation (42) that distinguished it from other materials for biomedical application. BP nanosheets (BPNSs) and BP quantum dots (BPQDs) have already been used for bioimaging (44–46), photothermal therapy (42, 43), photodynamic therapy (11, 47–49), and drug delivery platforms (10, 11). Due to the abovementioned unique advantages that graphene or TMDs cannot compete with, BP is considered as a kind of rising biomaterial with promising biomedical-related applications. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is as yet no example of a NIR-light–controlled hydrogel drug delivery platform reported.

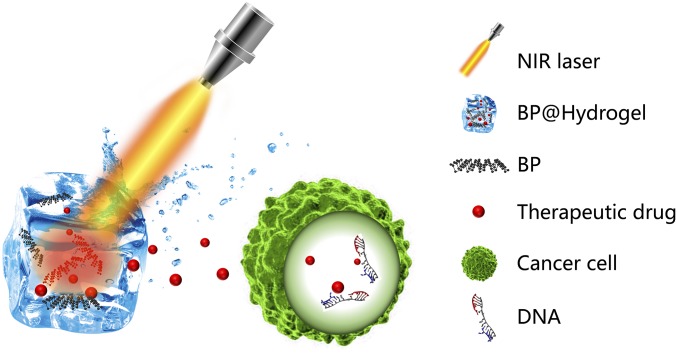

Herein, we report a more facile system, namely BP@Hydrogel which is the nanocomposite of BPNSs and hydrogel, that can be used to modulate the release of anticancer drugs under NIR light exposure, shown in Fig. 1. [Agarose is generally recognized as a safe material approved by American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) while BP has been justified as a harmless and degradable biomaterial.] A BP PTA can convert light to thermal energy and lead to the increasing temperature of the hydrogel matrix. Subsequently, the agarose hydrogel undergoes reversible hydrolysis and softening, leading to the accelerated diffusion of drug from the matrix to the environment. Controlled burst release may be advantageous to keep the released drugs within its therapeutic window, especially as therapeutic drugs often have nonlinear pharmacokinetics. More importantly, the hydrogel further hydrolyzes and melts under enhanced laser power and finally degrades into oligomers to be excreted through urine after the treatment. Therefore, this BP@Hydrogel drug delivery platform may not only enlarge the application fields of BP, but also exhibit potentials for clinical treatment of the cancer tumor.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the working principle of BP@Hydrogel. BP@Hydrogel released the encapsulated chemotherapeutics under NIR-light irradiation to broken the DNA chains, leading to the apoptosis induction.

Results

Morphology and Characterization.

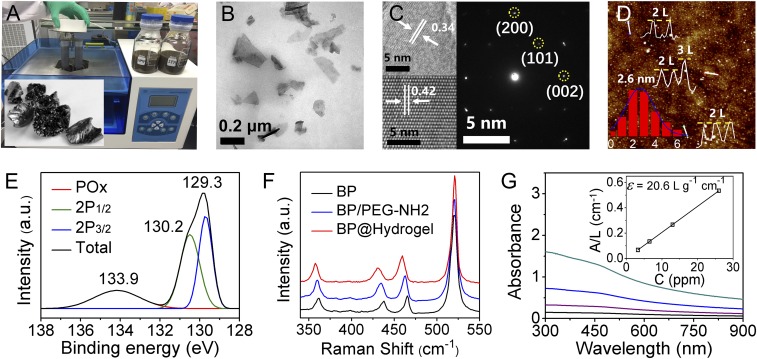

BPNSs were prepared by a modified liquid exfoliation method from bulk BP (Fig. 2A). Briefly, the cup ultrasound sonication with an ice bath of BP powder in isopropanol (IPA) was used to get ultrathin BPNSs with no sample contamination (Fig. 2B). As reported in a recent study, ultrasound probe sonication in NMP could easily achieve a large quantity of few-layered BP with high quality (42, 43). But the sample prepared from the above mentioned method was contaminated by the impurity from the tip during the probe sonication process, while our sample didn't direct contact with the tip during the cup sonication, to avoid the contamination of the sample, which is of benefit in biological applications. Finally, ultrathin BPNSs were obtained after centrifugation. BPNSs were functionalized with positively charged polyethylene glycol–amine (PEG-NH2) via electrostatic adsorption to improve their biocompatibility and physiological stability. After surface modification, the zeta potential of the BPQDs changed from −28.2 mV to −16.7 mV. The BPNSs exhibited enhanced stability in PBS solution after PEGylation. And the size distribution of BPNSs and PEGylated BPNSs measured from dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis, with average diameters of 155.6 nm and 160.3 nm, respectively, indicated a slight increase in size after PEGylation of BPNSs.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of BPNSs. (A) Biography of bulky BP and cup sonication device. (B) TEM of BP. (C) HR-TEM and electron diffraction of BP. (D) AFM, height profile, and thickness distributions of BPNSs. (E) XPS of BPNSs. (F) Raman spectra of BPNSs. (G) Absorbance spectra of BPNSs dispersed in IPA at different concentrations. G, Inset shows the normalized absorbance at concentrations of 3.25 ppm, 6.5 ppm, 13 ppm, and 26 ppm, respectively.

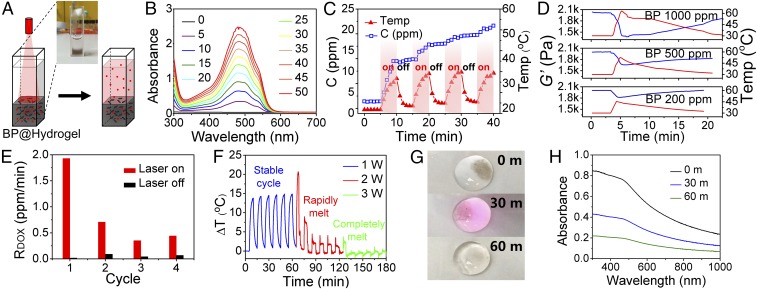

A BP-containing hydrogel depot named BP@Hydrogel was fabricated by using a low–melting-point agarose and PEGylated BPNSs. Here, BPNSs were mixed with an agarose aqueous solution at 60 °C, followed by the loading of different concentrations of doxorubicin (DOX) and rapid cooling down to room temperature to form the hydrogel matrix (Fig. 3A). It is worth noting that this BP@Hydrogel softens at 40∼45 °C and melts at 45∼50 °C. And the zeta potential of the BP@Hydrogel was −12.3 mV.

Fig. 3.

NIR-light–controlled BP@Hydrogel drug delivery platform. (A) Schematic representation of the BP@Hydrogel drug delivery platform and the physical map shown in Inset. (B) Absorbance spectra of released DOX. (C) Photocontrolled temperature increase and release of DOX from BP@Hydrogel depot. (D) Rheological curves (blue line) and corresponding temperature curves (red line) of BP@Hydrogel with different BP concentrations under 1 W⋅cm−2 NIR-light irradiation. (E) Release rate of DOX with and without laser exposure. (F) Temperature change vs. time under 808 nm laser with power of 1 W⋅cm−2 during 0∼60 min, 2 W⋅cm−2 during 60∼120 min, and 3 W⋅cm−2 during 120∼180 min. (G) BP@Hydrogel under different laser exposures. (H) Absorbance spectra of DOX under 808-nm laser exposure.

The morphology of BPNSs was characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM). The TEM images in Fig. 2B revealed that the lateral sizes of BPNSs were about 100∼200 nm. The diameter distribution of BPNSs measured from DLS analysis is shown in Fig. S1. The crystallinity of the few-layer BP (or phosphorene) was studied by high-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) (Fig. 2C) and selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) (Fig. 2C, Inset). Clear lattice fringes were observed from the BP atomic layer and those of 0.34 nm and 0.42 nm corresponding to the (021) and (014) planes of the BP crystal, respectively, which is consistent with well-known BP lattice parameters. The uniform lattices suggest that the phosphorene produced by IPA exfoliation retains the original crystalline state. According to the statistical AFM analysis of 200 BPNSs, shown in Fig. 2D, the average thickness was 2.6 ± 1.5 nm, corresponding to approximately one to eight layers of BPNSs.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed to determine the chemical composition of the BPNSs. The BPNSs show the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2doublets at 129.3 eV and 130.2 eV, respectively, which are characteristic of crystalline BP. Furthermore, the weak subband corresponding to oxidized phosphorus (i.e., POx) is apparent at 133.9 eV, indicating BPNSs could be well protected from being oxidized in IPA solvent.

A Raman spectrum was performed to characterize bare BP, PEGylated BP, and BP@Hydrogel, respectively (Fig. 2F). All of the samples showed nearly the same three characteristic Raman peaks attributed to one out-of-plane phonon mode, A1g at ∼361.0 cm−1, and two in-plane modes B2g and A2g at 438.0 cm−1 and 465.3 cm−1, respectively, suggesting that the prepared BP with organic modification did not lead to structural transformations compared with the corresponding bare BPNSs. Compared with bare BP, the A1g, B2g, and A2g modes of PEGylated BP and BP@Hydrogel were red shifted by about 2.2 cm−1, 4.5 cm−1, and 3.3 cm−1 and 4.5 cm−1, 9 cm−1, and 6.8 cm−1, respectively. A slight red shift was found after PEGylation and hydration with agarose, due to the adsorption after the addition of the PEG coating and hydration with agarose that hindered the oscillation of phosphorus atoms to some extent, thus decreasing the corresponding Raman scattering energy and leading to the red shift of the three Raman peaks of BPNSs.

The strong absorption in the NIR region is a prerequisite for the photothermal conversion. As is shown in Fig. 2G, the BPNSs from IPA exhibited broader and stronger absorption ranging from UV to NIR wavelengths. The extinction coefficient at 808 nm was estimated to be 20.6 L⋅g−1⋅cm−1 according to Beer–Lambert law (Fig. 2G, Inset), compared with 14.8 L⋅g−1⋅cm−1 in NMP, indicating its longer penetration depth and potential application for in-depth clinical treatment.

NIR-Light–Controlled Drug Releasing.

As shown above, the absorption spectra of BPNSs are stronger than those of BPQDs; therefore, an enhanced photothermal conversion efficiency is expected. The photothermal property of BPNSs was evaluated under an 808-nm NIR laser with a power density of 1.0 W⋅cm−2. According to the photothermal conversion efficiency calculation put forward by Roper et al. (49), the photothermal conversion efficiency (PTCE) of BPNSs is as high as 38.8%, which is stronger than that of the previous BPQDs at 28.4% (43), due to the larger extinction coefficient of BPNSs compared with BPQDs (details in SI Materials and Methods). Subsequently, NIR light with a wavelength of 808 nm was employed to investigate the photothermal effect of the embedded BPNSs on the release rate of the drug. The concentration of released drug in the PBS solution (pH 7.4) was monitored in real time, using a UV/Vis spectrometer. The light intensity was set to 1 W⋅cm−2 with an exposure time of 5 min (“ON”), followed by another 5 min under dark (“OFF”). The release rates, rON and rOFF, were calculated from the concentration–time slope with and without irradiation, respectively. A thermocouple was inserted into the BP@Hydrogel matrix (T1), while another one was affixed above the matrix (T2) and the temperature difference (ΔT) was measured over time. The experimental device is shown in Fig. 3A.

UV-Vis calibration curves were used to calculate the drug concentration from the UV-Vis absorbance. As can be seen in Fig. 3B, the absorbance spectra of DOX at 480 nm gradually increased, indicating the concentration of released DOX with the evolution of irradiation time. The photocontrolled temperature increase and release of DOX from the BP@Hydrogel depot is depicted in Fig. 3C, showing that the concentration of DOX increases dramatically under irradiation, compared with the unchanged concentration without irradiation. Rheology measurement of BP@Hydrogel with different BP concentrations indicated the reduction of the storage modulus at increasing BP concentration, shown in Fig. 3D. The release rates (rON and rOFF, in ppm⋅ml−1⋅min−1) during the presence or absence of visible light exposure were measured by the slope of the drug release profile. This calculated release rate is essentially the slope from the linear regression of the protein release profile at the start and the end of photomodulation. The drug release rates within the first four consecutive ON–OFF cycles are depicted in Fig. 3E. It can be seen that rON is much higher than rOFF, indicating that BP@Hydrogel could operate as an effective optical switch of drug release.

NIR-Light–Controlled BP@Hydrogel Degradation.

NIR-light–controlled degradability of BP@Hydrogel could improve its potential for clinical applications. To further assess the biodegradation of BP@Hydrogel, the temperature of the gel upon irradiation with a NIR laser was monitored over time. As can be seen from Fig. 3F, this BP@Hydrogel works well under low laser power with the temperature increased by more than 10 °C compared with an environmental temperature under 1 W⋅cm−2 irradiation. These cycles were repeated six times stably, with the hydrogel undergoing reversible softening. With the power of the laser increased to 1.5 W, the temperature increased dramatically, and the hydrogel became molten, leading to a gradually decreased temperature increase compared with the environmental temperature, as shown in Fig. 3F. In the meantime, both BP and DOX spread out and diffused all over the solution. And the BP@Hydrogel melted completely under 2 W⋅cm−2 irradiation. The NIR-light–controlled drug release and degradation process is illustrated in Fig. 1. When the BP@Hydrogel is exposed under NIR light, the hydrogel warms up and become softer under the photothermal effect of BPNSs due to the hydrolysis of cross-linking, leading to the release of drug. Further increasing the laser power results in the melting of the hydrogel and polymer degradation due to hydrolysis of the ester linkage into segments (reduced molecular weight), oligomers, and monomers and finally carbon dioxide and water. Degradation of the hydrogel disrupts the BPNSs and triggers release of the interior BPNSs which degrade rapidly if they are not protected by the hydrogel. The final degradation products from the BPNSs are nontoxic phosphate and phosphonate (47, 51), both of which are commonly found in the human body (52, 53). As shown in Fig. 3G, the dark colors of BP@Hydrogel gradually faded until nearly transparent under persistent irradiation, indicating that BP@Hydrogel almost degraded, which could be confirmed by the UV-Vis absorption spectra shown in Fig. 3H. Therefore, BP@Hydrogel could be degraded after the treatment, highlighting its large potential for clinical applications.

In Vitro Cell Experiments.

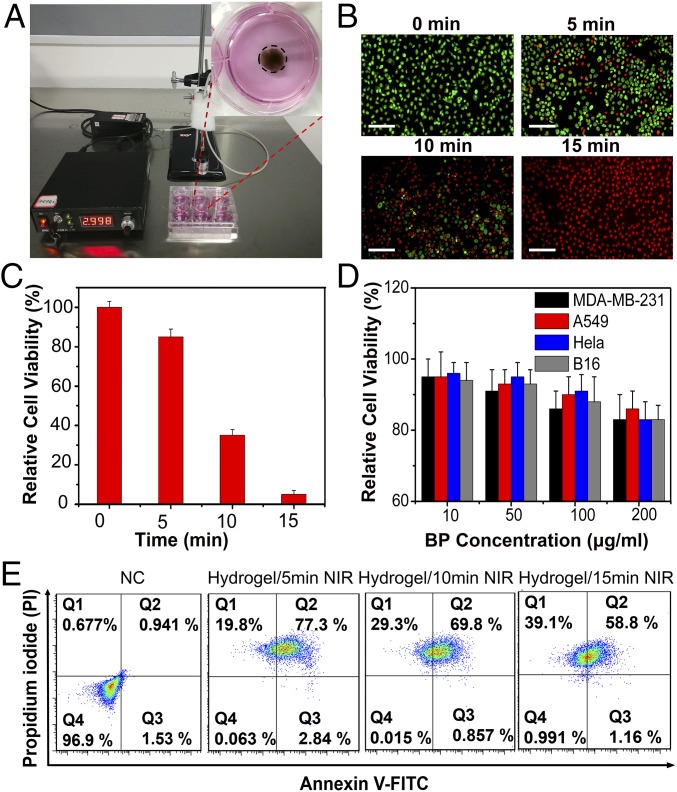

Biocompatibility is an important requisite for nanomaterials used in biomedicine. To verify the cytotoxicity of BPNSs, four types of human cells, including MDA-MB-231 (human breast cancer cells), A549 (A549 human lung carcinoma cells), HeLa (human cervical cancer cell), and B16 (mouse melanoma cells), were tested systematically. These cells were cultured with Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium containing different concentrations of BPNSs for 48 h, and the relative viabilities of cells were detected by Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) cell cytotoxicity assays. As shown in Fig. 4D, no obvious cytotoxicity could be observed for all cells selected even at a high concentration of 200 μg/mL, indicating a potential biosafety of this material.

Fig. 4.

In vitro cell viability experiment. (A) Photograph of MDA-MB-231 cell culture dish with BP@Hydrogel loaded with DOX. (B) Fluorescent images of acridine orange (green, live cells) and propidium iodide (red, dead cells) costained MDA-MB-231 cells after addition of BP@Hydrogel and exposure to laser irradiation for 0 min, 5 min, 10 min, and 20 min. (Scale bars: 100 μm.) (C) Relative cell viabilities of MDA-MB-231 cells treated with different laser irradiation times. (D) Relative cell viabilities of MDA-MB-231, A549, HeLa, and B16 cells with different BP concentrations (10 μg/mL, 50 μg/mL, 100 μg/mL, and 200 μg/mL). (E) Representative annexin V-FITC/PI scatter plots of 1 × 104 MDA-MB-231 cells after 24 h of treatment.

After confirming the biocompatibility of BPNSs, we next investigated their therapeutic effect in vitro. In the cell experiments, acridine orange/propidium iodide (live cells, green fluorescence; dead cells, red fluorescence) was used to differentiate the live/dead cells by costaining the cells. Under NIR-light laser for different times, the MDA-MB-231 cells were killed gradually by the released drugs as shown in Fig. 4B, and the relative cell viabilities were tested with the CCK-8 assay (Fig. 4C). Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide (PI) staining and FACS analysis demonstrated that the majority of the MDA-MB-231 cell death is due to apoptosis (Fig. 4E), and the difference between cell death and apoptosis may result from nonspecific cell death. These results demonstrated the potential applications for the NIR-light–controlled drug release to clinical cancer treatment. As shown in Fig. 4D, no obvious cytotoxicity could be observed for all cells selected, indicating a potential biosafety of this material.

In Vivo Tumor Eradication.

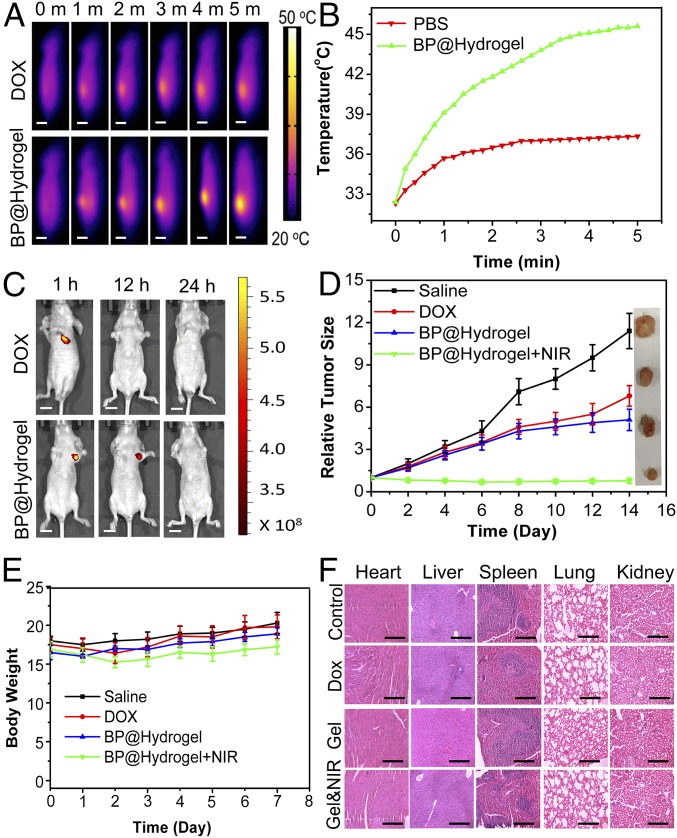

We carried out animal experiments to test the possibility of the BP@Hydrogel platform for in vivo application. We first studied the in vivo photothermal effects of our BP@Hydrogel platform. After intratumor injection of BP@Hydrogel and free DOX, respectively, animal NIR images and ΔT were monitored by a thermal camera during 5 min irradiation. ΔT of free DOX was only ∼5 °C while that of BP@Hydrogel was more than 13 °C, reaching more significant temperature rises throughout the irradiation period (Fig. 5 A and B). IVIS Spectrum was used to take the in vivo images and monitor the dynamic change of fluorescence at 1 h, 12 h, and 24 h postirradiation after the in vivo photothermal assay. As presented in Results, local intratumoral injection of BP@Hydrogel exhibited a localized drug distribution around the tumor site and more sustained release over 12 h than intratumoral injection of DOX only (Fig. 5C). Based on the in vivo therapeutic effects, we carried out an in vivo antitumor study to validate the enhanced therapy of cancer. The tumor-bearing nude mice were treated as follows: group 1, with saline (control); group 2, with DOX only; group 3, with BP@Hydrogel only; and group 4, with BP@Hydrogel with laser irradiation. The tumor volumes were calculated by the width and length every 2 d. At the end point of this experiment, all nude mice were killed and the tumors were collected. In line with the results of the tumor growth curve shown in Fig. 5D, the tumor sizes of the BP@Hydrogel depot with laser irradiation group were notably smaller than those of the other three groups. Consequently, these results demonstrated that the laser irradiation-controlled BP@Hydrogel-based drug delivery platform with DOX loaded possesses an excellent tumor ablation effect in vivo. Meanwhile, the body weights of nude mice were not significantly affected, demonstrating that there were no acute side effects in our combined therapy (Fig. 5E). To further evaluate the in vivo toxicity of BP@Hydrogel, major organs of the mice were sliced and stained by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histology analysis. As shown in Fig. 5F, the treated mice that were killed 2 wk after BP@Hydrogel injection with NIR irradiation exhibited no significant damage to the normal tissues, including the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney, indicating that BP@Hydrogel treatment had no observable side effect or toxicity to the normal tissues. Moreover, another s.c. tumor model of malignant melanoma in nude mice was also tested and validated the excellent in vivo therapeutic effect and biodegradability (Fig. S7 and SI Materials and Methods).

Fig. 5.

In vivo imaging and anticancer tumor effect of BP@Hydrogel drug delivery platform. (A) Thermal images of mice bearing tumors after injection of DOX or BP@Hydrogel, followed by exposure to 808-nm laser irradiation (1.0 W/cm2, 5 min). (Scale bars: 1 cm.) (B) Tumor temperature changes of mice bearing MDA-MB-231 tumors during laser irradiation as indicated in A. (C) Fluorescence images of mice at 1 h, 12 h, and 24 h postirradiation after the in vivo photothermal assay. The 485-nm wavelength light was used as the excitation source and 590 nm was detected as the emitted light. (Scale bars: 1 cm.) (D) Corresponding growth curves of tumors in different groups of mice treated with PBS solution, DOX, BP@Hydrogel depot only, and BP@Hydrogel depot with laser irradiation. The relative tumor volumes were normalized to their initial size. D, Inset shows representative photographs of tumors removed from the killed nude mice. (E) Body weight of nude mice recorded every other day after various treatments. (F) H&E-stained images of major organs from treated mice. (Scale bars: 50 μm.)

Discussion

A smart NIR-light–controlled drug-release BP@Hydrogel nanostructure is fabricated by using a low–melting-point agarose and PEGylated BPNSs. The solid state of BP@Hydrogel transforms to a gel state after injection into the cancerous tissue because of the lower body temperature, resulting in the phase transition. The BP@Hydrogel underwent controllable softening and molten states under NIR laser power, due to the high photothermal conversion efficiency of BPNSs, leading to a controllable light-triggered drug release and hydrogel degradation. More importantly, the drug release rate can be precisely tuned by internal (e.g., agarose, BP, and drug concentration) and external parameters as well (e.g., light intensity and exposure duration), which is beneficial for clinical application to maintain an effective blood drug concentration for anticancer therapy. Both in vitro and in vivo experiments show that BP@Hydrogel possesses an excellent cancer cell killing ability and tumor ablation effect. Notably, BP@Hydrogel has negligible toxicity for various classes of cells, and both the agarose hydrogel and BPNSs were degradable when the treatment was accomplished, which makes them promising for clinical translation. Consequently, we are able to conclude that the BP@Hydrogel-based drug delivery platform with low cytotoxicity and high biodegradability has a potential for on-demand and in-depth viscera therapeutics, such as breast and melanoma cancers. However, aiming at final clinical and translational applications of light-activated BP@Hydrogel and successful bench-to-bedside transition, future investigations concerning safety and facile inexpensive and controlled synthesis methods of high-quality BP nanomaterials with much higher efficiency and fewer side effects are crucially needed.

Materials and Methods

Reagents.

The BP crystals (Fig. 2A, Inset) were purchased from a commercial supplier (Smart-Elements) and stored in a dark Argon glovebox. NMP and IPA (99.5%, anhydrous) were purchased from Aladdin Reagents. PEG-NH2 and low–melting-point agarose were purchased from Yare Shanghai. Doxorubicin hydrochloride was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The AO/PI assay kit was obtained from Logos Biosystems. PBS (pH 7.4), FBS, RPMI-1640 medium, trypsin-EDTA, and penicillin/streptomycin were purchased from Gibco Life Technologies. All other chemicals used in this study were analytical reagent grade and used without further purification. Ultrapure water (18.25 MΩ/cm, 25 °C) was used to prepare all of the solutions.

In Vitro BP@Hydrogel Therapy Study.

Typically, MDA-MB-231cells were incubated in six-well plates at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h; afterward, the culture medium was replaced by new culture medium and the BP@Hydrogels (500 μg/mL BP, 200 μg/mL DOX, 1% LA) were put at the center of the wells. BP@Hydrogels were irradiated with an 808-nm laser at a power density of 1 W/cm2 for different times (0 min, 5 min, 10 min, 15 min). After incubation for another 6 h, both acridine orange and propidium iodide (live cells, green fluorescence; dead cells, red fluorescence) were used to costain the cells to determine the effect of BP@Hydrogel. To quantitatively analyze the therapy effect of BP@Hydrogel, cells were plated and incubated in 96-well plates at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air for 24 h. BP@Hydrogels were added and the cells continued incubating for another 6 h. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to an 808-nm NIR laser irradiation for 5 min. Finally, the viability of MDA-MB-231 cells was determined by a CCK-8 cell cytotoxicity assay. The cell viability was normalized by control group without any treatment.

In Vivo Photothermal Assay.

Tumor-bearing nude mice were injected with 100 μL of 200 μg/mL DOX (group 1) or 100 μL of BP@Hydrogel (500 μg/mL BP, 200 μg/mL DOX, 1% LA, group 2). After 1 h injection, the nude mice were irradiated with an 808-nm laser at 1 W/cm2 for 5 min. During the course of irradiation, an IR thermal camera (FLIR E50) was utilized to monitor the temperature changes of the tumor sites. All animal studies were conducted according to the experimental practices and standards approved by the Animal Welfare and Research Ethics Committee at Shenzhen University (Approval ID: 2017003).

In Vivo Biodistribution Analysis.

IVIS Spectrum (PerkinElmer) was used to take the in vivo images of mice at 1 h, 12 h, and 24 h postirradiation after the in vivo photothermal assay, respectively. A 485-nm wavelength light was used as the excitation source and 590 nm was detected as the emitted light.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research is partially supported by the National Natural Science Fund (Grants 61435010 and 61575089), the Science and Technology Innovation Commission of Shenzhen (Grants KQTD2015032416270385 and JCYJ20150625103619275), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant 2017M610540).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1714421115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kumar R, et al. Small conjugate-based theranostic agents: An encouraging approach for cancer therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:6670–6683. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00224a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Punglia RS, Morrow M, Winer EP, Harris JR. Local therapy and survival in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2399–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra065241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devadasu VR, Bhardwaj V, Kumar MN. Can controversial nanotechnology promise drug delivery? Chem Rev. 2013;113:1686–1735. doi: 10.1021/cr300047q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamaly N, Yameen B, Wu J, Farokhzad OC. Degradable controlled-release polymers and polymeric nanoparticles: Mechanisms of controlling drug release. Chem Rev. 2016;116:2602–2663. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Maciel D, Rodrigues J, Shi X, Tomás H. Biodegradable polymer nanogels for drug/nucleic acid delivery. Chem Rev. 2015;115:8564–8608. doi: 10.1021/cr500131f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Díaz B, et al. Tris DBA palladium is highly effective against growth and metastasis of pancreatic cancer in an orthotopic model. Oncotarget. 2016;7:51569–51580. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kay NE, et al. Tris (dibenzylideneacetone) dipalladium: A small-molecule palladium complex is effective in inducing apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B-cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57:2409–2416. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2016.1161186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la Puente P, et al. Tris DBA palladium overcomes hypoxia-mediated drug resistance in multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57:1677–1686. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2015.1099645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhandarkar SS, et al. Tris (dibenzylideneacetone) dipalladium, a N-myristoyltransferase-1 inhibitor, is effective against melanoma growth in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5743–5748. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tao W, et al. Black phosphorus nanosheets as a robust delivery platform for cancer theranostics. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1603276. doi: 10.1002/adma.201603276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen W, et al. Black phosphorus nanosheet-based drug delivery system for synergistic photodynamic/photothermal/chemotherapy of cancer. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1603864. doi: 10.1002/adma.201603864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin F, et al. Black phosphorus quantum dot based novel siRNA delivery systems in human pluripotent teratoma PA-1 cells. J Mater Chem B Mater Biol Med. 2017;5:5433–5440. doi: 10.1039/c7tb01068k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fojtů M, et al. Black phosphorus nanoparticles potentiate the anticancer effect of oxaliplatin in ovarian cancer cell line. Adv Funct Mater. 2017;27:1701955. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue Y, et al. Anti-VEGF agents confer survival advantages to tumor-bearing mice by improving cancer-associated systemic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18513–18518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807967105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu CF, et al. A zebrafish model discovers a novel mechanism of stromal fibroblast-mediated cancer metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:4769–4779. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svensson S, et al. CCL2 and CCL5 are novel therapeutic targets for estrogen-dependent breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3794–3805. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang X, et al. VEGF-B promotes cancer metastasis through a VEGF-A-independent mechanism and serves as a marker of poor prognosis for cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E2900–E2909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503500112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim S, Hosaka K, Nakamura M, Cao Y. Co-option of pre-existing vascular beds in adipose tissue controls tumor growth rates and angiogenesis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:38282–38291. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang D, et al. Antiangiogenic agents significantly improve survival in tumor-bearing mice by increasing tolerance to chemotherapy-induced toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4117–4122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016220108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vermonden T, Censi R, Hennink WE. Hydrogels for protein delivery. Chem Rev. 2012;112:2853–2888. doi: 10.1021/cr200157d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basuki JS, et al. Photo-modulated therapeutic protein release from a hydrogel depot using visible light. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;56:966–971. doi: 10.1002/anie.201610618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy LC, et al. A new era for cancer treatment: Gold-nanoparticle-mediated thermal therapies. Small. 2011;7:169–183. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirsch LR, et al. Nanoshell-mediated near-infrared thermal therapy of tumors under magnetic resonance guidance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13549–13554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232479100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang K, et al. Multimodal imaging guided photothermal therapy using functionalized graphene nanosheets anchored with magnetic nanoparticles. Adv Mater. 2012;24:1868–1872. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li M, Yang X, Ren J, Qu K, Qu X. Using graphene oxide high near-infrared absorbance for photothermal treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Adv Mater. 2012;24:1722–1728. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu SH, Chen YW, Hung WT, Chen IW, Chen SY. Quantum-dot-tagged reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites for bright fluorescence bioimaging and photothermal therapy monitored in situ. Adv Mater. 2012;24:1748–1754. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xuan J, et al. Organic-base-driven intercalation and delamination for the production of functionalized titanium carbide nanosheets with superior photothermal therapeutic performance. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:14569–14574. doi: 10.1002/anie.201606643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang S, et al. A facile one-pot synthesis of a two-dimensional MoS2/Bi2S3 composite theranostic nanosystem for multi-modality tumor imaging and therapy. Adv Mater. 2015;27:2775–2782. doi: 10.1002/adma.201500870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang S, et al. Injectable 2D MoS2-integrated drug delivering implant for highly efficient NIR-triggered synergistic tumor hyperthermia. Adv Mater. 2015;27:7117–7122. doi: 10.1002/adma.201503869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng L, et al. PEGylated WS(2) nanosheets as a multifunctional theranostic agent for in vivo dual-modal CT/photoacoustic imaging guided photothermal therapy. Adv Mater. 2014;26:1886–1893. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yong Y, et al. WS2 nanosheet as a new photosensitizer carrier for combined photodynamic and photothermal therapy of cancer cells. Nanoscale. 2014;6:10394–10403. doi: 10.1039/c4nr02453b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng W, et al. Flower-like PEGylated MoS2 nanoflakes for near-infrared photothermal cancer therapy. Sci Rep. 2015;5:17422. doi: 10.1038/srep17422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mao HY, et al. Graphene: Promises, facts, opportunities, and challenges in nanomedicine. Chem Rev. 2013;113:3407–3424. doi: 10.1021/cr300335p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khlebtsov N, Dykman L. Biodistribution and toxicity of engineered gold nanoparticles: A review of in vitro and in vivo studies. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:1647–1671. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00018c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li L, et al. Black phosphorus field-effect transistors. Nat Nanotechnol. 2014;9:372–377. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H, et al. Phosphorene: An unexplored 2D semiconductor with a high hole mobility. ACS Nano. 2014;8:4033–4041. doi: 10.1021/nn501226z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castellanos-Gomez A, et al. Isolation and characterization of few-layer black phosphorus. 2D Materials. 2014;1:025001. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia F, Wang H, Jia Y. Rediscovering black phosphorus as an anisotropic layered material for optoelectronics and electronics. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4458. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudenko AN, Katsnelson MI. Quasiparticle band structure and tight-binding model for single- and bilayer black phosphorus. Phys Rev B. 2014;89:201408. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qiao J, Kong X, Hu ZX, Yang F, Ji W. High-mobility transport anisotropy and linear dichroism in few-layer black phosphorus. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4475. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X, et al. Highly anisotropic and robust excitons in monolayer black phosphorus. Nat Nanotechnol. 2015;10:517–521. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shao J, et al. Biodegradable black phosphorus-based nanospheres for in vivo photothermal cancer therapy. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12967. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun Z, et al. Ultrasmall black phosphorus quantum dots: Synthesis and use as photothermal agents. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:11526–11530. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee HU, et al. Black phosphorus (BP) nanodots for potential biomedical applications. Small. 2016;12:214–219. doi: 10.1002/smll.201502756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun Z, et al. TiL4-coordinated black phosphorus quantum dots as an efficient contrast agent for in vivo photoacoustic imaging of cancer. Small. 2017;13:1602896. doi: 10.1002/smll.201602896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun C, et al. One-pot solventless preparation of PEGylated black phosphorus nanoparticles for photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy of cancer. Biomaterials. 2016;91:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang H, et al. Ultrathin black phosphorus nanosheets for efficient singlet oxygen generation. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:11376–11382. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang D, et al. Assembly of Au plasmonic photothermal agent and iron oxide nanoparticles on ultrathin black phosphorus for targeted photothermal and photodynamic cancer therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2017;27:1700371. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lv R, et al. Integration of upconversion nanoparticles and ultrathin black phosphorus for efficient photodynamic theranostics under 808 nm near-infrared light irradiation. Chem Mater. 2016;28:4724–4734. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roper DK, Ahn W, Hoepfner M. Microscale heat transfer transduced by surface plasmon resonant gold nanoparticles. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interface. 2007;111:3636–3641. doi: 10.1021/jp064341w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ling X, Wang H, Huang S, Xia F, Dresselhaus MS. The renaissance of black phosphorus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:4523–4530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416581112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Childers DL, Corman J, Edwards M, Elser JJ. Sustainability challenges of phosphorus and food: Solutions from closing the human phosphorus cycle. Bioscience. 2011;61:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pravst I. Risking public health by approving some health claims?–The case of phosphorus. Food Policy. 2011;36:726–728. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.