The sperm-specific Ca2+ channel CatSper (cation channel of sperm) controls the intracellular Ca2+ concentration and, thereby, the swimming behavior of sperm. Human CatSper is activated by progesterone (1, 2), an oviductal hormone, which stimulates Ca2+ influx and motility responses. By patch-clamp recording from human sperm, Mannowetz et al. (3) studied the action of the steroids pregnenolone sulfate (pregS), testosterone, hydrocortisone, and 17-β-estradiol (estradiol) as well as that of the plant triterpenoids pristimerin and lupeol on CatSper currents. Here, we report data that contradict most of these results.

We agree with Mannowetz et al. (3) that pregS activates CatSper, and that pregS and progesterone use the same binding site. We also observe that pregS enhances CatSper currents (Fig. 1 E and G); moreover, we show that pregS evokes a rapid Ca2+ influx (Fig. 1 A, C, and D) and that human sperm (from a patient with deafness-infertility syndrome) that lack CatSper do not respond to pregS (Fig. 1B). Using Ca2+ fluorimetry, we and others showed by cross-desensitization experiments that progesterone and its derivatives (e.g., 17-OH-progesterone) employ the same binding site to activate CatSper (1, 4). Similarly, sequential application of progesterone and pregS (and vice versa) leads to cross-desensitization (Fig. 1 J and K), confirming that both steroids act via the same binding site.

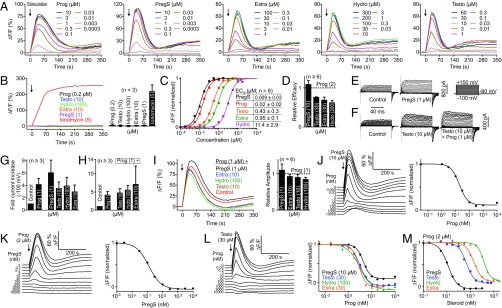

Fig. 1.

Steroid-evoked Ca2+ signals and membrane currents in noncapacitated human sperm. (A) Representative steroid-evoked Ca2+ signals. (B) Ca2+ signals in sperm from a patient with deafness-infertility syndrome lacking functional CatSper channels (5, 6). (C) Normalized dose–response relations and mean EC50 values. (D) Relative efficacy of steroids to evoke Ca2+ signals; maximal progesterone-evoked amplitude = 1. (E) Monovalent CatSper currents before (control) and after perfusion with pregS. (F) Currents before and after perfusion with testosterone followed by testosterone plus progesterone. (G) Mean fold steroid-induced increase of current amplitudes (control = 1). (H) Current increase evoked by the respective steroid plus progesterone in the presence of this steroid (current in the absence of any steroid = 1). (I) Ca2+ responses and mean relative signal amplitudes (progesterone = 1) evoked by progesterone alone and by progesterone plus steroid. (J) PregS-evoked Ca2+ responses in sperm preincubated in progesterone, and normalized signal amplitudes as a function of progesterone. (K) Progesterone-evoked Ca2+ responses in sperm preincubated in pregS, and normalized signal amplitudes plotted as a function of pregS. (L) Testosterone-evoked Ca2+ responses in sperm preincubated in progesterone, and normalized steroid-evoked signal amplitudes plotted as a function of the progesterone preincubation. (M) Normalized progesterone-evoked signal amplitude as a function of the steroid preincubation. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Methods are described elsewhere (1, 7). Estra, estradiol; Hydro, hydrocortisone; PregS, pregnenolone sulfate; Prog, progesterone; Testo, testosterone.

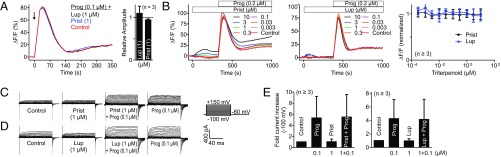

However, we disagree with the claim of Mannowetz et al. (3) that, by contrast to pregS, the steroids testosterone, hydrocortisone, and estradiol represent true antagonists that abolish CatSper activation by progesterone but themselves do not activate CatSper. Our data lead to entirely different conclusions. Testosterone, hydrocortisone, and estradiol all enhance CatSper currents (Fig. 1 F and G) and stimulate Ca2+ influx via CatSper (Fig. 1 A and B), although with different potency (Fig. 1C) and efficacy (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, these steroids do not antagonize progesterone-induced CatSper currents (Fig. 1 F and H), and simultaneous application of the steroids with progesterone does not antagonize progesterone-induced Ca2+ influx (Fig. 1I). Thus, testosterone, hydrocortisone, and estradiol, in fact, are agonists that activate CatSper rather than antagonists. Cross-desensitization experiments demonstrate that all these steroids use the same binding site to activate CatSper: Sequential application of progesterone and testosterone, hydrocortisone, or estradiol (and vice versa) leads to cross-desensitization (Fig. 1 L and M). Finally, Mannowetz et al. (3) claim that pristimerin and lupeol antagonize CatSper activation by progesterone. We fail to reproduce this result: Neither simultaneous application of these triterpenoids with progesterone nor preincubation affects progesterone-induced Ca2+ influx (Fig. 2 A and B), and progesterone-induced membrane currents were similar in the absence and presence of the triterpenoids (Fig. 2 C–E). Thus, pristimerin and lupeol do not antagonize CatSper activation by progesterone. Of note, at ≥3 μM, pristimerin alone, but not lupeol, evoked a sizeable Ca2+ increase (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Action of pristimerin and lupeol on progesterone-induced Ca2+ signals and membrane currents in noncapacitated human sperm. (A) Ca2+ signals evoked by progesterone (control) and by progesterone plus lupeol or pristimerin, and mean signal amplitudes evoked by progesterone plus triterpenoid (progesterone alone = 1). (B, Left and Middle) Ca2+ signals evoked by lupeol or pristimerin alone and by progesterone in the presence of the triterpenoids. (B, Right) Mean signal amplitudes evoked by progesterone in the presence of lupeol or pristimerin (progesterone alone = 1). (C) Monovalent CatSper currents before (control) and after perfusion with pristimerin and pristimerin plus progesterone, and by progesterone alone. (D) Currents before (control) and after perfusion with lupeol and lupeol plus progesterone, and by progesterone alone. (E) Mean fold increase of current amplitudes in the conditions described in C and D. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Methods are described elsewhere (1, 7). Lup, lupeol; Prist, pristimerin; Prog, progesterone.

These obvious discrepancies are likely not due to differences in buffer composition, voltage protocols, or drug concentrations. Considering that various steroids coexist in male and female reproductive fluids, it is required to distinguish between agonistic and antagonistic mechanisms of pharmacological action. Future studies need to address the physiological consequences and potential medical application of the promiscuous steroid-binding site controlling CatSper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by German Research Foundation Grants CRU326 (to T.S. and F.T.) and SFB1089 (to U.B.K.); Cells-in-Motion Cluster of Excellence (Münster) Grant CiM20027 (to T.S.); and a research fellowship from the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology (to I.V.W.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Strünker T, et al. The CatSper channel mediates progesterone-induced Ca2+ influx in human sperm. Nature. 2011;471:382–386. doi: 10.1038/nature09769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lishko PV, Botchkina IL, Kirichok Y. Progesterone activates the principal Ca2+ channel of human sperm. Nature. 2011;471:387–391. doi: 10.1038/nature09767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mannowetz N, Miller MR, Lishko PV. Regulation of the sperm calcium channel CatSper by endogenous steroids and plant triterpenoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:5743–5748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1700367114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schaefer M, Hofmann T, Schultz G, Gudermann T. A new prostaglandin E receptor mediates calcium influx and acrosome reaction in human spermatozoa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3008–3013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, et al. Sensorineural deafness and male infertility: A contiguous gene deletion syndrome. J Med Genet. 2007;44:233–240. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.045765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith JF, et al. Disruption of the principal, progesterone-activated sperm Ca2+ channel in a CatSper2-deficient infertile patient. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:6823–6828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216588110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiffer C, et al. Direct action of endocrine disrupting chemicals on human sperm. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:758–765. doi: 10.15252/embr.201438869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]