To the Editor

Cyclic neutropenia is a rare hematologic disease that is characterized by regular oscillations in blood neutrophil counts from normal levels (absolute neutrophil count [ANC], >1.5×109 per liter) to severe neutropenia (ANC, <0.2×109 per liter), usually with a cycle length of about 21 days.1 When patients with this disorder have neutropenia, they often have fever and mouth ulcers and are at risk for severe infections. Cyclic neutropenia is usually an autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in the gene encoding neutrophil elastase (ELANE).2

We first reported the use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) in patients with cyclic neutropenia 28 years ago.3 Shortly thereafter, a randomized clinical trial showed that G-CSF prevented infections in such patients.4 Subsequently, we followed these patients and 350 others, including 191 affected patients in 37 families, through the Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry (SCNIR), which records treatments, serious infections, hospitalizations, cancers, and deaths.5 We defined severe infection as hospitalization for infection requiring antibiotics (e.g., febrile neutropenia, pneumonia, bacteremia, and peritonitis).

The six patients in our original study are now between the ages of 38 and 94 years. Five of the six have ELANE mutations. The eldest, who does not have an ELANE mutation, had spontaneous improvement and stopped G-CSF. The other five patients have maintained good health while receiving G-CSF injections at least three times per week for nearly 30 years. One patient has decreased bone density, and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura developed in another; otherwise there have been no clinically significant complications. In aggregate, the six patients have received more than 6.6 g of G-CSF over approximately 150 patient-years of observation.

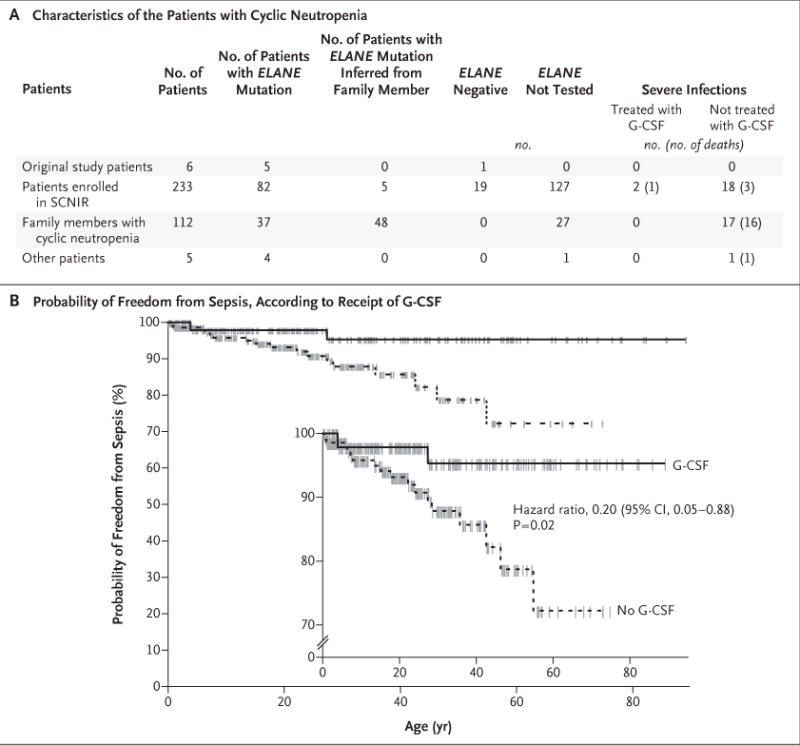

Figure 1A summarizes data for 356 patients with cyclic neutropenia. Among the 239 patients who have been prospectively followed through the SCNIR (including the 6 patients from our original study), there was a consistent history of recurrent fevers, mouth ulcers, and infections before the initiation of G-CSF.3 In this group, there have been 18 episodes of severe infection (3 of which were fatal in patients who did not have substantial coexisting illness) among the patients who were not receiving G-CSF and 2 episodes among those who were receiving G-CSF (including 1 patient who also had chronic renal failure). Kaplan–Meier analysis suggests that G-CSF prevents severe infections in patients with cyclic neutropenia (P = 0.02) (Fig. 1B). An analysis of the whole population of 356 patients, which included records from family histories, showed 36 episodes of sepsis in untreated patients, as compared with 2 in patients who were receiving G-CSF.

Figure 1. Characteristics of the Patients and Efficacy of G-CSF in the Prevention of Sepsis.

Panel A summarizes data for 356 patients with cyclic neutropenia, including 239 patients who have been followed through the Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry (SCNIR). Shown are data regarding the presence or absence of mutations in the gene encoding neutrophil elastase (ELANE) and the efficacy of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) in preventing severe infections. Patients’ family members who also had neutropenia were considered to have cyclic neutropenia. Panel B shows Kaplan–Meier plots comparing the probability of freedom from sepsis among the patients who received G-CSF and those who did not. The inset shows the same data on an expanded y axis. The hash marks indicate censoring of data owing to a loss of follow-up, including deaths unrelated to sepsis events. The hazard ratio for freedom from sepsis was calculated by means of a Cox proportional-hazards model with G-CSF as a time-varying covariate.

Adverse events have generally not limited G-CSF treatment of cyclic neutropenia. Bone pain, the most common adverse effect, usually abates with repeated injections. One patient who had never initiated treatment with G-CSF received a diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia that required hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. One G-CSF–treated patient who was receiving long-term chronic immunosuppressive therapy for Henoch–Schönlein purpura underwent hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Another patient underwent transplantation as a primary treatment for cyclic neutropenia. None of these patients survived.

Since our original report, we have recorded nearly 3000 patient-years of treatment with G-CSF without other hematologic complications or cases of AML in treated patients and no AML in any known family members. On the basis of these long-term observations, we believe that G-CSF is a remarkably safe and effective treatment to prevent infections and improve the quality of life in patients with cyclic neutropenia.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants (5R24AI049393 and UL1 TR002319) from the National Institutes of Health and a contract (AM 200811812) with the University of Washington from Amgen.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

Contributor Information

David C. Dale, University of Washington Seattle, WA

AudreyAnna Bolyard, University of Washington Seattle, WA

Tracy Marrero, University of Washington Seattle, WA.

Vahagn Makaryan, University of Washington Seattle, WA

MaryAnn Bonilla, St. Joseph’s Children’s Hospital, Paterson, NJ

Daniel C. Link, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO

Peter Newburger, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA

Akiko Shimamura, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA

Laurence A. Boxer, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Charles Spiekerman, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

References

- 1.Dale DC, Welte K. Neutropenia and neutrophilia. In: Kaushansky K, Lichtman MA, Prchal JT, et al., editors. Williams hematology. 9th. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2016. pp. 991–1004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horwitz M, Benson KF, Person RE, Aprikyan AG, Dale DC. Mutations in ELA2, encoding neutrophil elastase, define a 21-day biological clock in cyclic haematopoiesis. Nat Genet. 1999;23:433–6. doi: 10.1038/70544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammond WP, IV, Price TH, Souza LM, Dale DC. Treatment of cyclic neutropenia with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:1306–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198905183202003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dale DC, Bonilla MA, Davis MW, et al. A randomized controlled phase III trial of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (filgrastim) for treatment of severe chronic neutropenia. Blood. 1993;81:2496–502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dale DC, Cottle TE, Fier CJ, et al. Severe chronic neutropenia: treatment and follow-up of patients in the Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry. Am J Hematol. 2003;72:82–93. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]