Abstract

Aim

We compared the effects of two types of basal insulin: long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin, on diabetes‐related complications in type 1 diabetes.

Methods

A total of 1188 patients with type 1 diabetes who had recently started on long‐acting insulin analogues or intermediate/long‐acting human insulin were identified in 2004–2008 and followed until death or the end of 2013. Clinical outcomes included acute (i.e. hyperglycaemia, hypoglycaemia) and chronic (i.e. nephropathy, retinopathy, neuropathy, cardiovascular diseases) complications. Diabetes‐related complications were measured as a composite outcome which included acute and chronic complications. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the time to event hazard ratio. Three propensity score (PS) methods were applied to adjust for baseline imbalances between basal insulin groups, including the PS‐matching approach (as the main analysis), standardized mortality ratio weighting (SMRW) and inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW).

Results

Long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin had a lower risk for a composite of diabetes‐related complications {adjusted hazards ratios [aHRs] [95% confidence interval (CI)] 0.782 [0.639, 0.956], 0.743 [0.598, 0.924] and 0.699 [0.577, 0.846] according to the PS‐matching approach, SMRW and IPTW, respectively}. Compared with intermediate/long‐acting human insulin, using long‐acting insulin analogues had a lower hypoglycaemia risk: aHRs (95% CI) 0.681 (0.498, 0.930), 0.662 (0.466, 0.943) and 0.639 (0.471, 0.867) from the PS‐matching approach, SMRW and IPTW, respectively. No statistical differences were found between two types of insulin on individual chronic complications.

Conclusion

A trend of lower diabetes‐related complications associated with long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin was observed. A reduced hypoglycaemia risk with long‐acting insulin analogues was confirmed in this ‘real‐world’ study.

Keywords: diabetes‐related complications, hypoglycaemia, intermediate/long‐acting human insulin, long‐acting insulin analogues, type 1 diabetes

What is Already Known about this Subject

Around one‐third of type 1 diabetes patients have microvascular diseases, and the risk of macrovascular diseases among type 1 diabetes patients is higher compared with the general population.

The use of basal insulins, including long‐acting insulin analogues and intermediate/long‐acting human insulin, is important for achieving optimal glycaemic targets in type 1 diabetes patients.

Evidence on the effects of different basal insulins for long‐term diabetes‐related complications in type 1 diabetes patients has been lacking.

What this Study Adds

This longitudinal cohort study showed that type 1 diabetes patients using long‐acting insulin analogues had a significantly lower composite of diabetes‐related complications [including acute complications (i.e. hypoglycaemia) and chronic complications (i.e. cardiovascular and microvascular diseases)] compared with those using intermediate/long‐acting human insulin.

A reduced risk of hypoglycaemia associated with the use of long‐acting insulin analogues was supported in this observational cohort study.

The differences between long‐acting insulin analogues and intermediate/long‐acting human insulin in chronic diabetes‐related complications appeared to be small in this ‘real‐world’ setting.

Introduction

The incidence of type 1 diabetes is increasing worldwide, with an annual increase of about 3–5% 1, 2. The annual incidence rate of childhood (<15 years of age) type 1 diabetes in Taiwan was 5.3 per 100 000 children in 2003–2008 3. Type 1 diabetes reduces life expectancy and results in significant lifetime medical costs 4. The development of long‐term microvascular complications such as nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy, and macrovascular complications such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) is responsible for major morbidity and mortality in patients with type 1 diabetes 5, and these are key drivers of the economic burden for such individuals 6. As estimated, approximately 37% of young adults diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in childhood had serious microvascular complications 7. The risk of macrovascular diseases in patients with type 1 diabetes is at least 10 times that of the nondiabetic population 8, 9; such diseases are responsible for two‐thirds of death among type 1 diabetes patients 10, 11.

The pharmacological target of insulin is type II receptor tyrosine kinases (formerly known as insulin receptor family) 12. Insulin binds to the insulin receptor and its primary activity is the regulation of glucose metabolism by promoting glucose and amino acid uptake into cells, particularly into muscle and adipose tissues. Intensive insulin therapy that achieves optimal glycaemic control could provide benefits in reducing the risk of either developing or worsening vascular complications in diabetes. Major trials in type 1 diabetes have confirmed the role of haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)/glycaemic control in microvascular diseases 13, 14, 15, 16, 17. In addition, intensive glycaemic control has been shown to reduce CVD risks in patients with type 1 diabetes 18. Therefore, tight glycaemic control is critical for preventing the natural history of developing diabetes‐related vascular complications.

For type 1 diabetes, basal insulin, including long‐acting insulin analogues and intermediate/long‐acting human insulin, is an important treatment for achieving optimal glycaemic targets, and thus the potential effect of basal insulin on long‐term diabetes‐related complications would be of interest 15, 19. Basal insulin should be combined with prandial (rapid‐ or short‐acting) insulin in basal‐bolus schemes with multiple daily injections. Although the difference in reduced HbA1c level between long‐acting insulin analogues and intermediate/long‐acting human insulin may be small 20, long‐acting insulin analogues (e.g. glargine) have several advantages over intermediate/long‐acting human insulin, including significantly improved fasting blood glucose, less glucose variability and fewer hypoglycaemic episodes 21, 22, 23, 24, which may produce favourable vascular profiles.

There has been a lack of longitudinal studies to assess the impact of long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin on long‐term diabetes‐related complications in patients with type 1 diabetes. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on type 1 diabetes reported no difference in CVD (i.e. transient ischaemic attack, mortality due to myocardial infarction, or cardiopulmonary arrest) 25, 26, 27 or microvascular events 28, 29 between long‐acting insulin analogues and intermediate/long‐acting human insulin treatments. However, one limitation inherent to these RCTs is the relatively short length of the observation period (i.e. 16–32 weeks), which makes it difficult to capture any long‐term diabetes‐related complications. Although two observational cohort studies were conducted, in the United States 30 and Italy 31, respectively, to evaluate the effects of basal insulin on the risks of diabetes‐related complications, neither specifically targeted patients with type 1 diabetes. The present study thus aimed to evaluate the comparative risks of acute and chronic diabetes‐related complications of basal insulins (i.e. long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin) for patients with type 1 diabetes.

Materials and methods

The Institutional Review Board of National Cheng Kung University Hospital approved the study before commencement (B‐EX‐103‐015).

We utilized the Longitudinal Cohort of Diabetes Patients (LHDB) 1999–2013 from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) as a data source. Taiwan's NHIRD is population based and derived from the claims data of the National Health Insurance (NHI) programme, a mandatory‐enrolment, single‐payer system that covers over 99% of Taiwan's population 32. The LHDB is a valid national dataset that consists of a random sample of 120 000 de‐identified diabetes incident cases from each calendar year, who were tracked back to 1996 and followed up to 2013 to establish a longitudinal cohort. The LHDB is the most representative of Taiwan's population with diabetes and provides a research opportunity to evaluate the long‐term health outcomes of the patients.

Study cohort

The procedures for identifying patients with type 1 diabetes from the LHDB were based on previous studies 3, 33 and expert opinions (three experts from the field of endocrinology, paediatrics and family medicine, respectively). We selected the patients who: (i) had received a catastrophic illness certificate (CIC) for type 1 diabetes; (ii) had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes [International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) = 250.X1 or 250.X3] from the outpatient file of the LHDB during 1999–2008; and (iii) had been prescribed long‐acting insulin analogues (i.e. glargine, detemir) or intermediate/long‐acting human insulin [i.e. neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH), lente, ultralente) during 2004–2008. This period was chosen because glargine had been reimbursed by the NHI since February 2004. Insulin exposure was ascertained according to insulin prescriptions from the LHDB. The type of insulin was confirmed based on the labels and the drug licensure codes of insulin products from the Taiwan Food and Drug Administration (TFDA). A list of insulins in the NHI formularies between 1999 and 2015, and corresponding drug licensure codes from the TFDA are provided in Table S1. To exclude potential type 2 diabetes cases, we removed those prescribed with any oral antidiabetic agents (OADs), including sulphonylureas, meglitinides, alpha‐glucosidase inhibitors (e.g. acarbose), dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors and glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor agonists, after the CIC for type 1 diabetes had been issued. However, those on metformin alone, thiazolidinediones (TZDs) alone, or a combination of metformin and TZDs were retained in the cohort, mainly due to the fact that both metformin and TZDs are insulin sensitizers that can be combined with insulin treatments for patients with insulin resistance 34, 35, and that we have seen these two drugs prescribed in a number of patients with type 1 diabetes in Taiwan's practice setting as well as in published studies 34, 36. In addition, we allowed the inclusion of study patients exposed to OADs before the CIC for type 1 diabetes was issued, for the following two reasons. First, the patients may have been misclassified as having type 2 diabetes before they were confirmed as having type 1 diabetes (i.e. before the CIC was issued). Secondly, during the ‘honeymoon phase’ – i.e. in the early stage of type 1 diabetes – it is believed that β cells still have some preserved mass/functions for insulin secretion 37. In this circumstance, sulphonylureas, which stimulate insulin secretion from pancreatic cells, may still be effective for type 1 diabetes. In fact, we found around 10% of study patients who had been prescribed sulphonylureas before being confirmed as having type 1 diabetes (Table 1), while they had not been prescribed any OADs, except for metformin or TZDs, after the CIC for type 1 diabetes had been issued.

Table 1.

Patients' characteristics according to type of insulin before and after propensity score (PS) matching

| Baseline characteristics | Before PS matching | After PS matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long‐acting IA, n = 401 | Intermediate/long‐acting HI, n = 787 | P‐value | Long‐acting IA, n = 270 | Intermediate/long‐ acting HI, n = 270 | P‐value | |

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 21.31 ± 10.37 | 14.07 ± 10.23 | <0.0001 | 18.14 ± 8.69 | 18.21 ± 12.41 | 0.9328 |

| Female (%) | 54.86 | 52.22 | 0.3887 | 52.96 | 54.81 | 0.6660 |

| Year of index date (%) a | <0.0001 | 0.8594 | ||||

| 2004 | 7.73 | 13.47 | 10.74 | 9.26 | ||

| 2005 | 21.20 | 13.34 | 18.15 | 20.37 | ||

| 2006 | 22.44 | 51.59 | 29.26 | 29.26 | ||

| 2007 | 26.43 | 12.07 | 20.74 | 22.59 | ||

| 2008 | 22.19 | 9.53 | 21.11 | 18.52 | ||

| Diabetes duration (years) (mean ± SD) | 1.33 ± 1.85 | 1.53 ± 2.00 | 0.0994 | 1.35 ± 1.91 | 1.27 ± 1.93 | 0.6523 |

| CCI (mean ± SD) | 2.22 ± 0.65 | 2.17 ± 0.61 | 0.2161 | 2.16 ± 0.51 | 2.15 ± 0.53 | 0.7431 |

| History of DKA hospitalization (%) | 40.65 | 44.98 | 0.1544 | 47.78 | 46.30 | 0.7302 |

| History of HHS hospitalization (%) | 0.50 | 1.02 | 0.5094 | 0.74 | 0.00 | 0.4991 |

| History of hypoglycaemia (%) | 4.99 | 5.84 | 0.5418 | 5.56 | 5.19 | 0.8486 |

| History of dyslipidaemia (%) | 14.21 | 10.93 | 0.0997 | 10.74 | 12.22 | 0.5892 |

| History of hypertension (%) | 1.75 | 1.14 | 0.3946 | 1.11 | 1.85 | 0.7245 |

| Other insulins (1 year before index date) (%) | ||||||

| Short‐acting HI | 35.41 | 49.81 | <0.0001 | 37.78 | 37.41 | 0.9292 |

| Rapid‐acting IA | 17.46 | 15.12 | 0.2980 | 14.81 | 15.93 | 0.7204 |

| Premixed HI | 35.91 | 49.81 | <0.0001 | 37.41 | 35.56 | 0.6549 |

| Premixed IA | 28.43 | 6.99 | <0.0001 | 17.41 | 14.44 | 0.3468 |

| OADs (1 year before index date) (%) | ||||||

| Metformin | 18.20 | 6.10 | <0.0001 | 11.11 | 10.37 | 0.7810 |

| Sulphonylureas | 14.21 | 4.96 | <0.0001 | 9.26 | 10.00 | 0.7705 |

| Alpha‐glucosidase inhibitors | 4.49 | 1.52 | 0.0031 | 4.07 | 3.33 | 0.6486 |

| Meglitinide | 2.49 | 0.64 | 0.0110 | 1.48 | 1.48 | 1.0000 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 1.75 | 1.27 | 0.5145 | 0.74 | 1.11 | 1.0000 |

| CVD‐related medications 1 year before index date) (%) | ||||||

| Lipid‐lowering agents | 6.48 | 3.56 | 0.0221 | 4.81 | 4.81 | 1.0000 |

| β‐blockers | 5.74 | 2.67 | 0.0081 | 4.44 | 4.81 | 0.8377 |

| ACEI/ARB | 2.49 | 1.27 | 0.1213 | 1.85 | 2.96 | 0.3996 |

| Diuretics | 2.49 | 3.18 | 0.5104 | 2.96 | 4.07 | 0.4835 |

| CCBs | 0.75 | 1.02 | 0.7590 | 0.74 | 1.48 | 0.6858 |

| Antiarrhythmic agents | 0.25 | 0.38 | 1.0000 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 1.0000 |

| Digoxin | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.5524 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Nitrates | 0.25 | 0.51 | 0.6681 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 1.0000 |

| Antithrombotic drugs | 5.24 | 9.28 | 0.0147 | 6.30 | 4.44 | 0.3399 |

ACEI/ARB, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CIC, catastrophic illness certificate; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; HHS, hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state; HI, human insulin; IA, insulin analogues; NA, not available, OAD, oral antidiabetic agent; SD, standard deviation

Index year refers to the calendar year when the first long‐acting insulin analogues or intermediate/long‐acting human insulin were prescribed during 2004–2008

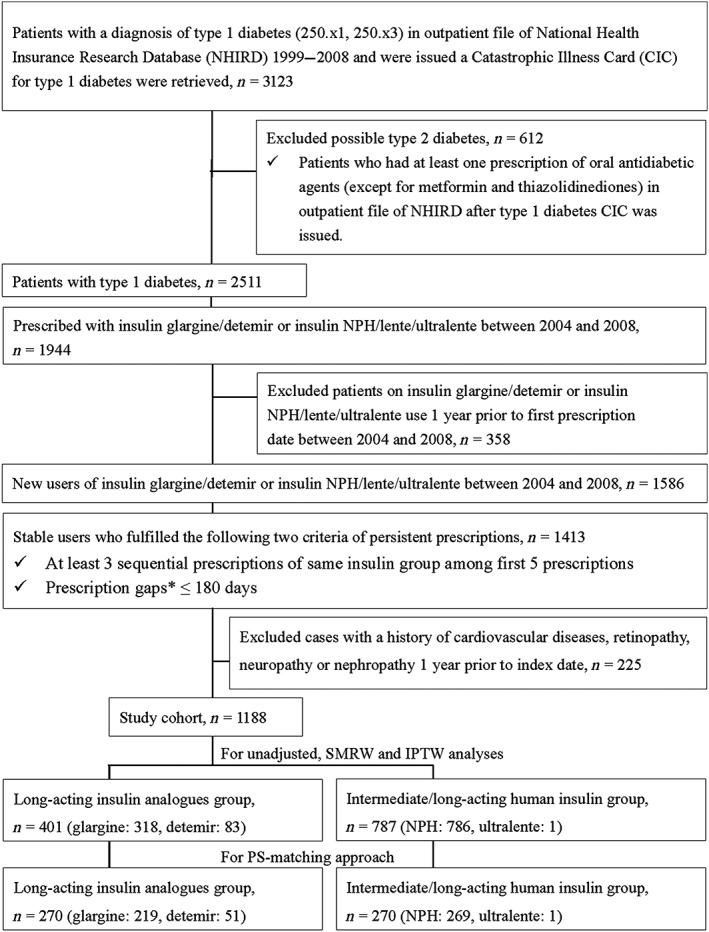

To select new users of basal insulin, we excluded those with a history of basal insulin use before the first claim date for basal insulin between 2004 and 2008. We then selected only stable basal insulin users, which were defined as having at least three consecutive insulin refills from the same insulin group among the first five prescriptions during 2004–2008, and any gaps between two consecutive refills of fewer than 180 days (‘grace period’). The definition of ‘stable’ users was based on our previous studies 4, 38 as well as our clinical observations of the prescription pattern of insulin use among patients with type 1 diabetes in Taiwan. The first claim date for stable prescriptions of basal insulin that met the criteria above was defined as the index date. Patients were classified into either long‐acting insulin analogue or intermediate/long‐acting human insulin users based on the type of basal insulin prescribed at the index date. Furthermore, we excluded those with a history of diagnosis of chronic diabetes‐related complications (i.e. CVD, nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy; listed in Table S2) within 1 year before the index date, in order to catch incident diabetes‐related complication events after the start of basal insulin. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we identified a total of 1188 type 1 diabetes patients who were newly treated with basal insulin (34% on long‐acting insulin analogues) and had no macrovascular or microvascular diseases before the index date (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study sample selection. IPTW, inverse probability treatment weighting; NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn; PS, propensity score; SMRW, standardized mortality ratio weighting. *Prescription gaps were defined using the following formula: a prescription gap = the next prescription date – (current prescription date + current number of prescription days)

Study outcomes

The outcomes of interest were any diabetes‐related complications as a composite outcome for diabetes‐related complications, including hospitalization for hyperglycaemia, outpatient or inpatient visits for hypoglycaemia, outpatient or inpatient visits for microvascular complications (i.e. nephropathy, retinopathy or neuropathy) or macrovascular complications (i.e. acute myocardial infarction, ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, stroke, cardiogenic shock, sudden cardiac arrest, atherosclerosis, CVD or arrhythmia), and all‐cause mortality. The study targeted defined hypoglycaemic events requiring medical assistance or intervention. Therefore, only outpatient visits and hospitalizations (including emergency room visits) for hypoglycaemia were counted. Death was ascertained based on the information on the CIC or in the inpatient files of the NHIRD, or discontinued enrolment from the NHI programme within 30 days of hospital discharge 39. The ICD‐9‐CM disease diagnosis and procedure codes for the identification of study outcomes of interest are summarized in Table S2.

Statistics

We used student's t‐test to examine the mean differences among continuous variables, and used the chi‐square test, Fisher test or Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test to examine the heterogeneity in the distributions of categorical variables.

Our primary analysis was performed as ‘intent‐to‐treat’ (ITT), whereby all patients were followed from the index date until a specific complication occurred, dropout from the NHI programme, death or the end of 2013. The crude incidence rate of complication events was calculated as the total number of events divided by the person‐years at risk accumulated over the follow‐up period. To adjust for baseline dissimilarities in potential confounders, we performed propensity score (PS) matching as the primary analysis, using the nearest neighbour approach with a ratio of 1:1 40 to yield two comparable treatment groups (i.e. long‐acting insulin analogues and intermediate/long‐acting human insulin groups). As recommended, the variable selection for estimating propensity scores is preferable to including either those variables that affect only study outcome(s) or those variables that affect both treatment section and the outcome(s) 41. The propensity scores were thus calculated by using a logistic regression model in which treatment status (i.e. receipt of long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin) was a dependent variable, and a list of independent variables which we considered to be associated with diabetes‐related complications and/or the selection of basal insulin: age and gender at index date, the year of index date, diabetes duration (i.e. the time from diabetes onset to index date), comorbidity history from 1 year before index date (i.e. hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, hospitalization for diabetic ketoacidosis, hospitalization for the hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state, hypoglycaemia, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and a composite comorbidity score measured by Charlson Comorbidity Index 42), and medication history from 1 year before the index date, including: other insulins (e.g. short‐acting insulin, rapid‐acting insulin), OADs (e.g. sulphonylureas) and CVD‐related medications (e.g. lipid‐lowering agents, β‐blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, diuretics, calcium channel blockers, antiarrhythmic agents, digoxin, nitrates or antithrombotic agents). Cox proportional hazards regression (using the PROC PHREG function in SAS) was applied to evaluate the time to diabetes‐related complication events between the matched insulin groups. We plotted the graph of the log[−log(survival)] vs. log of the survival time (using the PROC LIFETEST function in SAS), which resulted in parallel curves, implying that the variables in the Cox model satisfied the proportional hazards assumption 43. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for statistical analysis.

In addition to the aforementioned PS‐matching procedures, two other approaches [inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) and standardized mortality ratio weighting (SMRW)] were performed to make our results more generalizable. This is because, by using these approaches, all cohort patients would be retained for analyses. In contrast, only a certain proportion of cohort patients who were comparable between two insulin groups can be selected for analyses when using the PS‐matching approach. For IPTW, inverse probability treatment weights are defined as the inverse of the estimated PS for treated patients and the inverse of 1 minus the estimated PS for control patients. For SMRW, treated patients are given a weight of 1, while weights for control patients are defined as the ratio of the estimated PS to 1 minus the estimated PS. Furthermore, we stabilized weights to increase precision in the estimated treatment effects from the IPTW analysis 44. To adjust for unmeasured confounding (e.g. HbA1c) and decrease bias, patients at the 5th to 95th percentiles of distribution of PS strata were trimmed/eliminated 44. An IPTW‐ or SMRW‐based Cox proportional hazards model was then used to evaluate the risk of diabetes‐related complications, whereby the weights were derived from a PS that models the probability of treatment assignment (i.e. long‐acting insulin vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin). Hazard ratios (HRs), adjusted HRs (aHRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed from the Cox model. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A series of sensitivity analyses was conducted. Firstly, the aforementioned analyses were conducted based on the ‘on‐treatment’ scenario, whereby patients were censored when they switched to or added another type of basal insulin, or discontinued basal insulin treatment, in addition to the censored points in our primary analyses based on ITT (i.e. event occurred, death, dropout from the NHI programme, end of 2013). Secondly, we excluded those who had macrovascular or microvascular disease during the first three basal insulin prescriptions (the period used to identify stable users) and changed the index date to the third prescription date of stable use of basal insulin, in order to avoid immortal time bias. Thirdly, we used 60 days as a grace period, which was a stricter criterion for identifying stable insulin users. Fourthly, the effect of insulin on chronic complications may take some time, so we conducted a lag‐time analysis, whereby patients with chronic complication events that occurred 3 years after the initiation of insulin were excluded. Fifthly, basal insulin is typically accompanied by short/rapid‐acting insulin or even premixed insulin, which may influence the outcomes of study interest (i.e. hypoglycaemia, diabetes‐related complications). So, we adjusted for short/rapid‐acting insulin or premixed insulin, along with the use of basal insulin at the index date, as covariates in the Cox models. Finally, a stratification analysis was conducted; the aforementioned primary analyses were stratified by age at the first diagnosis of type 1 diabetes (i.e. early onset: 0–12 years; late onset: ≥13 years).

Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 45, and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 12.

Results

The number of patients included for unadjusted analyses, SMRW and IPTW were 401 and 787 for long‐acting insulin analogues and intermediate/long‐acting human insulin, respectively, while that for the PS‐matching analysis were 270 and 270 for long‐acting insulin analogues and intermediate/long‐acting human insulin, respectively (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the patients' characteristics stratified by the type of basal insulin. Before the PS matching, patients on long‐acting insulin analogues were older and used more premixed insulin, metformin, TZDs and CVD medications (i.e. lipid‐lowering agents, β‐blockers). However, these patients' characteristics were no longer different between the two insulin groups after PS matching, IPTW or SMRW. Additional information about patients' characteristics is provided in Table S3. The analyses were conducted for any diabetes‐related complications (as a composite outcome) and for each particular complication, separately. The follow‐up times for each specific complication are provided in Table S4.

Table 2 summarizes the incidence rates of diabetes‐related complications and adjusted HR data associated with the use of long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin. Comparing long‐acting insulin analogues with intermediate/long‐acting human insulin, the adjusted HRs (95% CI) estimated from the PS‐matching approach were 0.304 (0.084, 1.106), 1.027 (0.673, 1.568), 0.918 (0.689, 1.223), 1.169 (0.710, 1.925), 0.910 (0.670, 1.237), 0.681 (0.498, 0.930), 0.592 (0.424, 0.828), 1.622 (0.830, 3.170), 0.782 (0.639, 0.956) and 0.502 (0.092, 2.739), for CVD, nephropathy, retinopathy, neuropathy, hospitalization for hyperglycaemia, any hypoglycaemia, outpatient hypoglycaemia, hospitalization for hypoglycaemia, any complications, and all‐cause death, respectively. The incidence rates of any hypoglycaemia, outpatient hypoglycaemia and any diabetes‐related complications were lower for long‐acting insulin analogues users than for intermediate/long‐acting human insulin users. The use of long‐acting insulin analogues was associated with significantly lower risks of any diabetes‐related complications, any hypoglycaemia, and outpatient hypoglycaemia compared with those with the use of intermediate/long‐acting human insulin. The use of long‐acting insulin analogues was associated with significantly reduced risks of any diabetes‐related complications at aHRs of 0.782 (95% CI 0.639, 0.956), 0.743 (95% CI 0.598, 0.924) and 0.699 (95% CI 0.577, 0.846) estimated from the PS‐matching approach, SMRW and IPTW, respectively. Compared with patients on intermediate/long‐acting human insulin, those on long‐acting insulin analogues had aHRs of 0.681 (95% CI 0.498, 0.930), 0.662 (95% CI 0.466, 0.943) and 0.639 (95% CI 0.471, 0.867) for any hypoglycaemia according to the PS‐matching approach, SMRW and IPTW, respectively. The unadjusted HR data are provided in Table S5.

Table 2.

Incidence rates (per 1000 person‐years), and hazard ratios of acute complications (hyperglycaemia, hypoglycaemia), chronic complications (macrovascular and microvascular diseases) and death for type 1 diabetes patients on long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin using different propensity score approaches

| PS‐matching approacha | SMRW with PS trimming 5–95th percentiles | IPTW with PS trimming 5–95th percentiles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long‐acting IA, IR (events) | Intermediate/long‐acting HI, IR (events) | aHR (95% CI) | aHR (95% CI) | aHR (95% CI) | |

| CVD | 1.6 (3) | 5.2 (10) | 0.304 (0.084–1.106) | 0.255 (0.054–1.211) | 0.324 (0.085–1.227) |

| Nephropathy | 24.3 (43) | 23.7 (43) | 1.027 (0.673–1.568) | 1.049 (0.671–1.639) | 0.998 (0.671–1.482) |

| Retinopathy | 58.5 (89) | 64.1 (98) | 0.918 (0.689–1.223) | 0.928 (0.684–1.259) | 0.872 (0.668–1.139) |

| Neuropathy | 18.5 (33) | 15.6 (29) | 1.169 (0.710–1.925) | 1.030 (0.616–1.721) | 1.075 (0.675–1.711) |

| Hospitalization for hyperglycaemia | 49.4 (77) | 54.0 (87) | 0.910 (0.670–1.237) | 0.738 (0.525–1.039) | 0.725 (0.537–0.979)* |

| Any hypoglycaemia | 41.7 (68) | 61.8 (94) | 0.681 (0.498–0.930)* | 0.662 (0.466–0.943)* | 0.639 (0.471–0.867)* |

| Outpatient hypoglycaemia | 33.0 (56) | 56.6 (88) | 0.592 (0.424–0.828)* | 0.582 (0.400–0.847)* | 0.547 (0.392–0.765)* |

| Hospitalization for hypoglycaemia | 12.0 (22) | 7.4 (14) | 1.622 (0.830–3.170) | 1.012 (0.497–2.058) | 1.238 (0.705–2.173) |

| Any complications | 169.8 (173) | 224.7 (210) | 0.782 (0.639–0.956)* | 0.743 (0.598–0.924)* | 0.699 (0.577–0.846)* |

| All‐cause death | 1.0 (2) | 2.0 (4) | 0.502 (0.092–2.739) | 0.257 (0.028–2.351) | 0.210 (0.023–1.931) |

aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HI. human insulin; IA, insulin analogues; IPTW, inverse probability treatment weighting; IR, incidence rate per 1000 person‐years; PS, propensity score; SMRW, standardized mortality ratio weighting

Variables included in the PS model were age, gender, index year, diabetes duration, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and also comorbidity and co‐medications from 1 year before the index date (including hospitalization for diabetic ketoacidosis, hospitalization for the hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state, hypoglycaemia, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, other insulins, oral antidiabetic agents and cardiovascular disease‐related medications). After PS matching, SMRW and IPTW with PS trimming, all covariates were balanced and there was no need for additional adjustment in the Cox model

P < 0.05

The results of sensitivity analyses are presented in Table 3. The results from the scenarios (except for scenario 1, ‘on‐treatment’) are consistent with those from the primary analyses shown in Table 2. However, in scenario 1 ‘on‐treatment’, only the result for outpatient hypoglycaemia is significant. Moreover, the baseline characteristics of the study cohort indicated that a few patients had prior use of CVD‐related medications (i.e. antiarrhythmic agents, digoxin, nitrates and antithrombotic drugs; see Table 1). We further excluded these patients from the study cohort and re‐ran the analyses. The results (Table S6) were consistent with those from the primary analyses. Table 4 shows the results stratified by age at the onset of type 1 diabetes, and a significantly lower risk for outpatient hypoglycaemia associated with the use of long‐acting insulin analogues was observed in early‐onset type 1 diabetes.

Table 3.

Incidence rates (per 1000 person‐years) and hazard ratios of acute complications (hyperglycaemia, hypoglycaemia), chronic complications (macrovascular and microvascular diseases) and death in propensity‐score‐matched cohorts of type 1 diabetes patients on long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin (different scenarios of sensitivity analyses)

| Incidence rate per 1000 person‐years (events) | aHR (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1: On‐treatment analysis | Long‐acting IA | Intermediate/long‐acting HI | |

| CVD | 2.0 (3) | 3.9 (4) | 0.510 (0.113–2.301) |

| Nephropathy | 19.0 (27) | 20.6 (20) | 0.940 (0.524–1.684) |

| Retinopathy | 54.6 (67) | 63.9 (55) | 0.944 (0.658–1.353) |

| Neuropathy | 16.1 (23) | 12.0 (12) | 1.460 (0.724–2.947) |

| Hospitalization for hyperglycaemia | 48.4 (63) | 48.0 (44) | 1.126 (0.765–1.659) |

| Any hypoglycaemia | 41.1 (54) | 66.2 (55) | 0.700 (0.479–1.024) |

| Outpatient hypoglycaemia | 31.0 (42) | 62.0 (52) | 0.568 (0.377–0.857)* |

| Hospitalization for hypoglycaemia | 11.6 (17) | 6.9 (7) | 1.871 (0.773–4.531) |

| Any complications | 165.3 (147) | 220.5 (133) | 0.865 (0.682–1.097) |

| All‐cause death | 0.7 (1) | 1.9 (2) | 0.412 (0.037–4.585) |

| Scenario 2: Avoid potential immortal time bias | |||

| CVD | 2.0 (4) | 4.5 (9) | 0.479 (0.147–1.559) |

| Nephropathy | 23.5 (43) | 26.4 (48) | 0.888 (0.588–1.340) |

| Retinopathy | 54.2 (87) | 58.6 (93) | 0.936 (0.698–1.253) |

| Neuropathy | 16.5 (31) | 17.0 (32) | 0.968 (0.590–1.586) |

| Hospitalization for hyperglycaemia | 43.7 (72) | 50.3 (82) | 0.872 (0.635–1.197) |

| Any hypoglycaemia | 36.3 (62) | 55.4 (90) | 0.656 (0.475–0.907)* |

| Outpatient hypoglycaemia | 30.0 (53) | 52.1 (86) | 0.578 (0.410–0.813)* |

| Hospitalization for hypoglycaemia | 10.6 (20) | 10.4 (20) | 1.019 (0.548–1.895) |

| Any complications | 151.7 (171) | 211.2 (207) | 0.750 (0.612–0.919)* |

| All‐cause death | 1.0 (2) | 1.5 (3) | 0.715 (0.119–4.299) |

| Scenario 3: Using a prescription gap of ≤60 days to indicate stable users | |||

| CVD | 1.2 (2) | 4.7 (8) | 0.265 (0.056–1.249) |

| Nephropathy | 21.5 (33) | 21.8 (35) | 0.992 (0.616–1.596) |

| Retinopathy | 57.1 (76) | 61.8 (83) | 0.925 (0.678–1.263) |

| Neuropathy | 17.9 (28) | 18.1 (29) | 0.985 (0.586–1.656) |

| Hospitalization for hyperglycaemia | 43.4 (60) | 50.4 (70) | 0.853 (0.604–1.204) |

| Any hypoglycaemia | 39.6 (56) | 65.8 (86) | 0.606 (0.433–0.849)* |

| Outpatient hypoglycaemia | 30.5 (45) | 62.1 (82) | 0.497 (0.346–0.716)* |

| Hospitalization for hypoglycaemia | 12.0 (19) | 10.3 (17) | 1.165 (0.605–2.241) |

| Any complications | 162.2 (150) | 227.2 (183) | 0.736 (0.593–0.914)* |

| All‐cause death | 0.6 (1) | 0.6 (1) | 1.004 (0.063–16.057) |

| Scenario 4: Lag‐time analysis for chronic complications | |||

| CVD | 1.5 (2) | 4.4 (6) | 0.359 (0.072–1.782) |

| Nephropathy | 10.4 (14) | 13.3 (18) | 0.790 (0.393–1.588) |

| Retinopathy | 21.3 (28) | 26.0 (34) | 0.807 (0.489–1.331) |

| Neuropathy | 9.0 (12) | 8.8 (12) | 1.000 (0.449–2.226) |

| All‐cause death | 0.7 (1) | 1.4 (2) | 0.542 (0.049–5.991) |

| Scenario 5: Additional adjustment for the potential confounding effects of other insulins (i.e. short‐acting insulin, rapid‐acting insulin, premix HI, premix IA) at the index date in the Cox model | |||

| CVD | 1.6 (3) | 5.2 (10) | 0.392 (0.090–1.698) |

| Nephropathy | 24.3 (43) | 23.7 (43) | 0.992 (0.602–1.636) |

| Retinopathy | 58.5 (89) | 64.1 (98) | 0.792 (0.566–1.108) |

| Neuropathy | 18.5 (33) | 15.6 (29) | 1.234 (0.674–2.257) |

| Hospitalization for hyperglycaemia | 49.4 (77) | 54.0 (87) | 0.937 (0.651–1.348) |

| Any hypoglycaemia | 41.7 (68) | 61.8 (94) | 0.663 (0.462–0.952)* |

| Outpatient hypoglycaemia | 33.0 (56) | 56.6 (88) | 0.593 (0.403–0.873)* |

| Hospitalization for hypoglycaemia | 12.0 (22) | 7.4 (14) | 1.493 (0.673–3.313) |

| Any complications | 169.8 (173) | 224.7 (210) | 0.712 (0.558–0.908)* |

| All‐cause death | 1.0 (2) | 2.0 (4) | 0.902 (0.120–6.795) |

aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HI, human insulin; IA, insulin analogues

aHRs and 95% CIs were based on a PS‐matching approach

P < 0.05

Table 4.

Incidence rates (per 1000 person‐years) and adjusted hazard ratios of acute complications (hyperglycaemia, hypoglycaemia), chronic complications (macrovascular and microvascular diseases) and death in propensity score‐matched cohorts of type 1 diabetes patients on long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin (stratification by age at the first diabetes diagnosis)

| Age group, n (no. of long‐acting IA vs. no. of intermediate/long‐ acting HI) | Incidence rate per 1000 person‐years (events) | aHR (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long‐acting IA | Intermediate/long‐ acting HI | |||

| CVD | 0–12 (75/75) | 1.9 (1) | 0.0 (0) | NA |

| ≧13 (182/182) | 0.7 (1) | 5.9 (8) | 0.132 (0.016–1.056) | |

| Nephropathy | 0–12 (75/75) | 22.4 (11) | 15.8 (8) | 1.393 (0.560–3.465) |

| ≧13 (182/182) | 23.7 (29) | 30.5 (38) | 0.777 (0.479–1.259) | |

| Retinopathy | 0–12 (75/75) | 47.8 (21) | 64.0 (27) | 0.750 (0.424–1.327) |

| ≧13 (182/182) | 60.7 (64) | 56.4 (61) | 1.080 (0.760–1.533) | |

| Neuropathy | 0–12 (75/75) | 0.0 (0) | 3.7 (2) | NA |

| ≧13 (182/182) | 27.8 (34) | 25.5 (32) | 1.077 (0.665–1.746) | |

| Hospitalization for hyperglycaemia | 0–12 (75/75) | 51.7 (22) | 49.3 (22) | 1.022 (0.566–1.847) |

| ≧13 (182/182) | 41.9 (47) | 48.3 (54) | 0.866 (0.586–1.280) | |

| Any hypoglycaemia | 0–12 (75/75) | 39.1 (17) | 64.9 (27) | 0.606 (0.330–1.112) |

| ≧13 (182/182) | 41.3 (48) | 46.4 (53) | 0.883 (0.597–1.305) | |

| Outpatient hypoglycaemia | 0–12 (75/75) | 21.3 (10) | 69.6 (29) | 0.368 (0.176–0.766)* |

| ≧13 (182/182) | 36.1 (43) | 46.4 (53) | 0.772 (0.516–1.154) | |

| Hospitalization for hypoglycaemia | 0–12 (75/75) | 23.3 (11) | 7.5 (4) | 3.042 (0.968–9.562) |

| ≧13 (182/182) | 9.3 (12) | 5.9 (8) | 1.513 (0.618–3.700) | |

| Any complications | 0–12 (75/75) | 162.4 (47) | 193.8 (54) | 0.850 (0.575–1.257) |

| ≧13 (182/182) | 176.0 (124) | 205.1 (137) | 0.873 (0.685–1.114) | |

| All‐cause death | 0–12 (75/75) | 1.9 (1) | 1.9 (1) | 1.038 (0.065–16.609) |

| ≧13 (182/182) | 0.7 (1) | 2.9 (4) | 0.261 (0.029–2.340) | |

aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HI, human insulin; IA, insulin analogues; NA, not available

aHRs and 95% CIs were based on a PS‐matching approach

P < 0.05

Discussion

We believe that the present study is the first to utilize a large and longitudinal cohort of newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients to evaluate the comparative risks of acute complications (i.e. hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia), chronic complications (i.e. microvascular and macrovascular diseases) and all‐cause mortality associated with the use of long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin. The study extends previous knowledge of short‐term differences in glycaemic control, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety between long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin, to address the issue of whether the strengths of long‐acting insulin analogues over intermediate/long‐acting human insulin (i.e. lower fasting blood glucose, less fluctuation of blood glucose and lower risk of hypoglycaemia 20) produce the benefits in altering risks of long‐term diabetes‐related complications in type 1 diabetes.

Previous RCTs on type 1 diabetes with a relatively limited follow‐up period (e.g. 16 weeks 25) and sample size (e.g. 130 22) found no difference in macrovascular diseases 25, 26, 27 or microvascular events 28, 29 between long‐acting insulin analogue and intermediate/long‐acting human insulin users. Although the present ‘real‐world’ study included 1188 type 1 diabetes cases with a median follow‐up of 7.39 years for chronic diabetes‐related complications (i.e. CVD, microvascular diseases), the differences between these two types of basal insulin on individual macrovascular and microvascular complications still appeared small.

Consistent with previous RCTs 25, 26, 27, a significantly reduced hypoglycaemia risk with long‐acting insulin analogues was confirmed in the current study. As hypoglycaemia is a potential contributor to CVD 46, a significantly lower risk of this condition with the use of long‐acting insulin analogues may be associated with favourable vascular outcomes. In fact, a trend of a lower incidence rate of CVD in long‐acting insulin vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin observed in the present study of type 1 diabetes is consistent with that found in a previous study of type 2 diabetes 30.

Two observational cohort studies have assessed the effects of basal insulins on diabetes‐related complications. Based on an integrated claims database in the United States, Juhaeri et al. 30 reported a lower, but nonsignificant, risk of myocardial infarction associated with the use of long‐acting insulin analogues (i.e. glargine) compared with intermediate/long‐acting human insulin (HR 0.81; 95% CI 0.65, 1.02). Recently, Cammarota et al. 31 conducted a 3‐year longitudinal, retrospective cohort study in Italy and found that, compared with patients on intermediate/long‐acting human insulin, glargine users had significantly lower risks of a composite of diabetes‐related complications (including macrovascular, microvascular and metabolic complications) (HR 0.57; 95% CI 0.44, 0.74) and a composite of macrovascular complications (HR 0.61; 95% CI 0.44, 0.84), and a lower, but nonsignificant, risk of microvascular complications (HR 0.58; 95% CI 0.33, 1.04).

However, Juhaeri et al. 30 targeted only type 2 diabetes, and the study by Cammarota et al. 31 was not able to differentiate between type 1 and type 2 diabetes with confidence. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to target type 1 diabetes to provide longitudinal evidence for the risk of diabetes‐related complications associated with the use of basal insulin. Similar to the findings of Cammarota et al. 31, we found a significantly lower risk of a composite of diabetes‐related complications (including CVD, microvascular diseases, hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia) among long‐acting insulin analogue users compared with those on intermediate/long‐acting human insulin.

The study had several methodological strengths to be emphasized. First, the definition of type 1 diabetes in our study considered not only the approaches from previous studies 33, but also clinical expertise from clinicians. Previous studies had used only the CIC and diagnosis codes of 250.x1 or x3 to define type 1 diabetes 33, while the present study additionally excluded potential type 2 diabetes cases (i.e. those prescribed OADs after the CIC was issued). We found that about 20% of the patients receiving the CIC for type 1 diabetes (612 out of 3123 in Figure 1) had been prescribed at least one OAD, except for metformin or TZDs, after the CIC was issued. And, 10% of study patients were prescribed with sulphonylureas at baseline (as shown in Table 1), while they had not been prescribed any OADs, except for metformin or TZDs, after the CIC for type 1 diabetes had been issued. We extracted study patients based on criteria for the selection of type 1 diabetes cohort that were different from those of previous studies 33, 47. We found that the study subjects in whom potential type 2 diabetes was excluded after the CIC was issued had similar characteristics to possible type 1 diabetes cases. The characteristics of possible study cases of type 1 diabetes patients based on various identification approaches are summarized in Table S7. For example, the study subjects based on our approach (i.e. excluding potential type 2 diabetes cases) were younger, had had fewer CVD events and had a lower frequency of lipid‐lowering agent use compared with subjects selected based on the approaches of previous studies 33, 47. We suggest that further validation of type 1 diabetes cases is warranted to verify the validity of different identification approaches (i.e. 250.xx and CICs 47, 250.x1 or 250.x3 and CICs 33, 250.x1 or 250.x3, CICs, and excluding potential type 2 diabetes cases via OADs). Second, we developed tools for measuring insulin exposure from the NHIRD in Taiwan (Table S1), which is expected to promote future utilization studies and outcomes research into insulin use in Taiwan. Third, with regard to the potential problem of confounding bias due to the nature of observational studies, we applied different adjustment strategies (i.e. PS matching, IPTW, SMRW). The PS‐matching approach tends to find matched/similar patients to be compared, and, therefore, a certain proportion of the study sample may be excluded if no similar cases can be identified. This may reduce the generalizability of study results. By contrast, IPTW and SMRW retain the whole study sample and adjust patients' baseline differences using weights, which guarantees the generalizability of findings. The IPTW method creates a synthetic sample, whereby the weighted treatment and control groups are representative of the patient characteristics in the overall population 48, while SMRW reweights the control patients to be representative of the treated population 44. Another strength of SMRW is that it is not affected by further uncontrolled confounding attributable to the inability to find an exact match for each treated subject 49. Most importantly, the results from different methods were consistent, which supports the validity of our study results. In addition, a series of sensitivity analyses (e.g. on‐treatment scenario) was conducted to ensure the robustness of our findings.

Study limitations

Despite the aforementioned strengths of the study, several limitations should be addressed. First, the diagnoses of type 1 diabetes and diabetes‐related complications relied fully on ICD‐9‐CM codes, which may be subject to disease misclassification. However, the type 1 diabetes cohort was formed using the LHDB, and all research information was retrieved from the medical claims in the NHIRD, which have a low likelihood of recall bias, a low likelihood of nonresponse and a low loss to follow‐up of cohort members. Moreover, the diagnosis and procedure codes of diabetes‐related complications used in the study have been used in previous diabetes studies (as summarized in Table S2). Some validation studies for CVD (e.g. myocardial infarction 50, stroke 51) have shown high sensitivity and positive predictive values to identify CVD events by using the diagnosis codes in Taiwan's NHIRD. Additionally, for some diseases (e.g. ischaemic heart disease, stroke, retinopathy), we used disease and procedure codes alike to confirm disease status, which may have reduced the bias of disease misclassification. Second, the present study addressed only defined hypoglycaemic events requiring medical assistance (i.e. an outpatient visit or hospitalization for hypoglycaemia), but we did not measure the full extent of hypoglycaemic events. Therefore, we may have underestimated the number of hypoglycaemic events. Third, we did not include degludec as one of the long‐acting insulin analogues because this agent is not currently reimbursed by Taiwan's NHI programme. Fourth, we did not control for the type of insulin administration, which may have affected the complication of interest. For example, insulin pump therapy, known as continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, may facilitate glycaemic control and thus reduce the risk of diabetes‐related complications. However, insulin pumps are not commonly used in Taiwan because they are relatively expensive and not reimbursed by the NHI programme. Fifth, by using claims data alone, we were unable to differentiate between people with latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) (a form of type 1 diabetes developing later in adulthood – typically at 30–50 years of age) and those with type 1 diabetes in childhood. However, according to the mean ages (± their standard deviations) for long‐acting insulin analogues and intermediate/long‐acting human insulin (i.e. 18.14 ± 8.69 and 18.21 ± 12.41 years of age, respectively) in the present study, there may have been few cases with LADA in our cohort. Sixth, the nature of the observational design of the study may raise the concern of confounding by indication. However, we applied several adjustment strategies (i.e. PS matching, SMRW with PS trimming 5–95th percentiles, IPTW with PS trimming 5–95th percentiles) to minimize baseline imbalances between different basal insulin users, and the results from different adjustment strategies appear consistent, which implies that our findings were robust. In addition, various sensitivity and stratification analyses were performed, which corroborated the validity of our findings. Moreover, we adjusted only for the differences in patients' characteristics at baseline (i.e. the index date) and did not further conduct time‐varying analyses to control potential changes during the follow‐up (e.g. the change in the pattern of short‐acting insulin use). Seventh, potential residual confounding by incomplete adjustment for unmeasured factors (e.g. HbA1c, lifestyle risk factors, physicians' behaviours or preference) for study outcomes may be unavoidable. For example, in practice, physicians may pay more attention to patients treated with intermediate/long‐acting human insulin, in terms of their hypoglycaemic events (i.e. more likely to ask about their experiences of hypoglycaemia in daily life when they come to clinic visits), compared with those taking long‐acting insulin analogues. This is a potential detection bias, leading to more hypoglycaemic events being observed in the intermediate/long‐acting human insulin group. Without adjusting for such behaviour by physicians, the relative benefit of long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin for hypoglycaemia in the present study may have been overestimated. The median observational period for chronic diabetes‐related complications (i.e. 7.39 years) in the present study may be considered relatively short. Moreover, the mean age of the study cohort at the index date was young (i.e. the mean ages for long‐acting insulin analogues and intermediate/long‐acting human insulin were 18.14 years and 18.21 years, respectively; see Table 1). These factors may have resulted in the relatively low frequency of macrovascular diseases (i.e. CVD) observed in the study, reducing the power of the study to detect the long‐term effects of insulin. However, the incidence rate of microvascular diseases (e.g. retinopathy) was still significantly sufficient for study. The study involved a number of hypothesis tests without making adjustments for inflated type 1 error, making it subject to false‐positive findings. The significant findings observed should thus be interpreted with caution. Lastly, our results may not be generalizable to other ethnicities or other health insurance settings, mainly because the healthcare delivered to Taiwan's population may not be the same as that in other countries.

Conclusions

The present ‘real‐world’ study involved longitudinal observation of diabetes‐related complications associated with the use of basal insulin among patients with type 1 diabetes. We found a trend of a potential benefit of long‐acting insulin analogues over intermediate/long‐acting human insulin on diabetes‐related complications, which mainly consisted of a significantly reduced risk of hypoglycaemia and a low incidence rate of CVD associated with the use of long‐acting insulin analogues. However, the differences between these two types of basal insulin in individual chronic complications may be marginal in this real‐world setting. A prospective trial with a long‐term follow‐up is warranted to verify our findings, and this will have important clinical implications for the care of type 1 diabetes patients.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

The authors gratefully thank National Cheng Kung University and its affiliated hospital for all their support. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, grant [MOST 104–2320‐B‐006‐008‐MY3].

Contributors

H.T.O. contributed substantially to the study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. T.Y.L. contributed to data collection and the analysis. Y.F.D. and C.Y.L. provided clinical and statistical interpretation of the results. H.T.O. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and T.Y.L., Y.F.D. and C.Y.L. critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave approval for the publication of the final version.

Supporting information

Table S1 Measurement tool for defining insulin exposure in Taiwan

Table S2 International Classification of Disease, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD 9‐CM) codes used to define study outcomes

Table S3 Additional patient characteristics according to type of insulin before and after propensity score (PS) matching

Table S4 Follow‐up time to each specific complication (time to event occurring or censored) in propensity score‐matched cohorts of type 1 diabetes patients

Table S5 Crude rates (per 1000 person‐years) and unadjusted hazard ratios of acute complications (hyperglycaemia, hypoglycaemia), chronic complications (macrovascular and microvascular diseases) and death in type 1 diabetes patients on long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin

Table S6 Incidence rates (per 1000 person‐years) and hazard ratios of acute complications (hyperglycaemia, hypoglycaemia), chronic complications (macrovascular and microvascular diseases) and death in propensity‐score‐matched cohorts of type 1 diabetes patients on long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin (subgroup analysis: patients without CVD‐related medications, e.g. antiarrhythmic agents, digoxin, nitrates and antithrombotic drugs, 1 year before index date)

Table S7 Comparison of patient characteristics from different approaches to the identification of type 1 diabetes

Ou, H.‐T. , Lee, T.‐Y. , Du, Y.‐F. , and Li, C.‐Y. (2018) Comparative risks of diabetes‐related complications of basal insulins: a longitudinal population‐based cohort of type 1 diabetes 1999–2013 in Taiwan. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 84: 379–391. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13461.

References

- 1. Soltesz G, Patterson CC, Dahlquist G. Worldwide childhood type 1 diabetes incidence – what can we learn from epidemiology? Pediatr Diabetes 2007; 8 (Suppl. 6): 6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyurus E, Green A, Soltesz G. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989–2003 and predicted new cases 2005–20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet 2009; 373: 2027–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lu CL, Shen HN, Chen HF, Li CY. Epidemiology of childhood type 1 diabetes in Taiwan, 2003 to 2008. Diabet Med 2014; 31: 666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ou HT, Yang CY, Wang JD, Hwang JS, Wu JS. Life expectancy and lifetime health care expenditures for type 1 diabetes: a nationwide longitudinal cohort of incident cases followed for 14 years. Value Health 2016; 19: 976–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nathan DM, Genuth S, Lachin J, Cleary P, Crofford O, Davis M, et al The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long‐term complications in insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 977–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gray A, Fenn P, McGuire A. The cost of insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) in England and Wales. Diabet Med 1995; 12: 1068–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bryden KS, Dunger DB, Mayou RA, Peveler RC, Neil HA. Poor prognosis of young adults with type 1 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 1052–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Laing SP, Swerdlow AJ, Slater SD, Burden AC, Morris A, Waugh NR, et al Mortality from heart disease in a cohort of 23,000 patients with insulin‐treated diabetes. Diabetologia 2003; 46: 760–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dorman JS, Laporte RE, Kuller LH, Cruickshanks KJ, Orchard TJ, Wagener DK, et al The Pittsburgh insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) morbidity and mortality study Mortality results. Diabetes 1984; 33: 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borch‐Johnsen K, Nissen H, Henriksen E, Kreiner S, Salling N, Deckert T, et al The natural history of insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus in Denmark: 1. Long‐term survival with and without late diabetic complications. Diabet Med 1987; 4: 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krolewski AS, Warram JH, Christlieb AR, Busick EJ, Kahn CR. The changing natural history of nephropathy in type I diabetes. Am J Med 1985; 78: 785–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, et al The concise guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: catalytic receptors. Br J Pharmacol 2015; 172: 5979–6023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. The DCCT Research Group . Diabetes control and complications trial (DCCT): results of feasibility study. Diabetes Care 1987; 10: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. The relationship of glycemic exposure (HbA1c) to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes 1995; 44: 968–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sustained effect of intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus on development and progression of diabetic nephropathy: the epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications (EDIC) study. JAMA 2003; 290: 2159–2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Effect of intensive therapy on the microvascular complications of type 1 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2002; 287: 2563–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lachin JM, Genuth S, Cleary P, Davis MD, Nathan DM. Retinopathy and nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes four years after a trial of intensive therapy. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 381–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, Genuth SM, Lachin JM, Orchard TJ, et al Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2643–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nathan DM, Zinman B, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, Genuth S, Miller R, et al Modern‐day clinical course of type 1 diabetes mellitus after 30 years' duration: the diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications and Pittsburgh epidemiology of diabetes complications experience (1983‐2005). Arch Intern Med 2009; 169: 1307–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tricco AC, Ashoor HM, Antony J, Beyene J, Veroniki AA, Isaranuwatchai W, et al Safety, effectiveness, and cost effectiveness of long acting versus intermediate acting insulin for patients with type 1 diabetes: systematic review and network meta‐analysis. BMJ 2014; 349: g5459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bolli GB, Songini M, Trovati M, Del Prato S, Ghirlanda G, Cordera R, et al Lower fasting blood glucose, glucose variability and nocturnal hypoglycaemia with glargine vs NPH basal insulin in subjects with type 1 diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2009; 19: 571–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Monami M, Marchionni N, Mannucci E. Long‐acting insulin analogues vs. NPH human insulin in type 1 diabetes. A meta‐analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009; 11: 372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Valensi P, Cosson E. Is insulin detemir able to favor a lower variability in the action of injected insulin in diabetic subjects? Diabetes Metab 2005; 31 (4 Pt 2): 4s34–4s39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peterson GE. Intermediate and long‐acting insulins: a review of NPH insulin, insulin glargine and insulin detemir. Curr Med Res Opin 2006; 22: 2613–2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kolendorf K, Ross GP, Pavlic‐Renar I, Perriello G, Philotheou A, Jendle J, et al Insulin detemir lowers the risk of hypoglycaemia and provides more consistent plasma glucose levels compared with NPH insulin in type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2006; 23: 729–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pieber TR, Draeger E, Kristensen A, Grill V. Comparison of three multiple injection regimens for type 1 diabetes: morning plus dinner or bedtime administration of insulin detemir vs. morning plus bedtime NPH insulin. Diabet Med 2005; 22: 850–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ratner RE, Hirsch IB, Neifing JL, Garg SK, Mecca TE, Wilson CA. Less hypoglycemia with insulin glargine in intensive insulin therapy for type 1 diabetes. US Study Group of Insulin Glargine in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2000; 23: 639–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Raskin P, Klaff L, Bergenstal R, Halle JP, Donley D, Mecca T. A 16‐week comparison of the novel insulin analog insulin glargine (HOE 901) and NPH human insulin used with insulin lispro in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2000; 23: 1666–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Standl E, Lang H, Roberts A. The 12‐month efficacy and safety of insulin detemir and NPH insulin in basal‐bolus therapy for the treatment of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2004; 6: 579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Juhaeri J, Gao S, Dai WS. Incidence rates of heart failure, stroke, and acute myocardial infarction among type 2 diabetic patients using insulin glargine and other insulin. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009; 18: 497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cammarota S, Bruzzese D, Catapano AL, Citarella A, De Luca L, Manzoli L, et al Lower incidence of macrovascular complications in patients on insulin glargine versus those on basal human insulins: a population‐based cohort study in Italy. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2014; 24: 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheng TM. Taiwan's new national health insurance program: genesis and experience so far. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003; 22: 61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hsu PC, Lin WH, Kuo TH, Lee HM, Kuo C, Li CY. A population‐based cohort study of all‐cause and site‐specific cancer incidence among patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus in Taiwan. J Epidemiol 2015; 25: 567–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vella S, Buetow L, Royle P, Livingstone S, Colhoun HM, Petrie JR. The use of metformin in type 1 diabetes: a systematic review of efficacy. Diabetologia 2010; 53: 809–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Strowig SM, Raskin P. The effect of rosiglitazone on overweight subjects with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 1562–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Faichney JD, Tate PW. Metformin in type 1 diabetes: is this a good or bad idea? Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Belle TL, Coppieters KT, von Herrath MG. Type 1 diabetes: etiology, immunology, and therapeutic strategies. Physiol Rev 2011; 91: 79–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ou HT, Chang KC, Liu YM, Wu JS. Recent trends in the use of antidiabetic medications from 2008 to 2013: a nation‐wide population‐based study from Taiwan. J Diabetes 2017; 9: 256–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lien HM, Chou SY, Liu JT. Hospital ownership and performance: evidence from stroke and cardiac treatment in Taiwan. J Health Econ 2008; 27: 1208–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dehejia RH, Wahba S. Propensity score‐matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Rev Econ Stat 2002; 84: 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Austin PC, Grootendorst P, Normand SL, Anderson GM. Conditioning on the propensity score can result in biased estimation of common measures of treatment effect: a Monte Carlo study. Stat Med 2007; 26: 754–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994; 47: 1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time to Event Data, 2nd edn, Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brookhart MA, Wyss R, Layton JB, Sturmer T. Propensity score methods for confounding control in nonexperimental research. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013; 6: 604–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SPH, et al The IUPHAR/BPS guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucl Acids Res 2016; 44: D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Frier BM, Schernthaner G, Heller SR. Hypoglycemia and cardiovascular risks. Diabetes Care 2011; 34 (Suppl 2): S132–S137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lin WH, Wang MC, Wang WM, Yang DC, Lam CF, Roan JN, et al Incidence of and mortality from type I diabetes in Taiwan from 1999 through 2010: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS One 2014; 9: e86172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res 2011; 46: 399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kurth T, Walker AM, Glynn RJ, Chan KA, Gaziano JM, Berger K, et al Results of multivariable logistic regression, propensity matching, propensity adjustment, and propensity‐based weighting under conditions of nonuniform effect. Am J Epidemiol 2006; 163: 262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cheng CL, Lee CH, Chen PS, Li YH, Lin SJ, Yang YH. Validation of acute myocardial infarction cases in the national health insurance research database in Taiwan. J Epidemiol 2014; 24: 500–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hsieh CY, Chen CH, Li CY, Lai ML. Validating the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke in a National Health Insurance claims database. J Formos Med Assoc 2015; 114: 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Measurement tool for defining insulin exposure in Taiwan

Table S2 International Classification of Disease, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD 9‐CM) codes used to define study outcomes

Table S3 Additional patient characteristics according to type of insulin before and after propensity score (PS) matching

Table S4 Follow‐up time to each specific complication (time to event occurring or censored) in propensity score‐matched cohorts of type 1 diabetes patients

Table S5 Crude rates (per 1000 person‐years) and unadjusted hazard ratios of acute complications (hyperglycaemia, hypoglycaemia), chronic complications (macrovascular and microvascular diseases) and death in type 1 diabetes patients on long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin

Table S6 Incidence rates (per 1000 person‐years) and hazard ratios of acute complications (hyperglycaemia, hypoglycaemia), chronic complications (macrovascular and microvascular diseases) and death in propensity‐score‐matched cohorts of type 1 diabetes patients on long‐acting insulin analogues vs. intermediate/long‐acting human insulin (subgroup analysis: patients without CVD‐related medications, e.g. antiarrhythmic agents, digoxin, nitrates and antithrombotic drugs, 1 year before index date)

Table S7 Comparison of patient characteristics from different approaches to the identification of type 1 diabetes