Abstract

Whole-exome and targeted sequencing of 13 individuals from 10 unrelated families with overlapping clinical manifestations identified loss-of-function and missense variants in KIAA1109 allowing delineation of an autosomal-recessive multi-system syndrome, which we suggest to name Alkuraya-Kučinskas syndrome (MIM 617822). Shared phenotypic features representing the cardinal characteristics of this syndrome combine brain atrophy with clubfoot and arthrogryposis. Affected individuals present with cerebral parenchymal underdevelopment, ranging from major cerebral parenchymal thinning with lissencephalic aspect to moderate parenchymal rarefaction, severe to mild ventriculomegaly, cerebellar hypoplasia with brainstem dysgenesis, and cardiac and ophthalmologic anomalies, such as microphthalmia and cataract. Severe loss-of-function cases were incompatible with life, whereas those individuals with milder missense variants presented with severe global developmental delay, syndactyly of 2nd and 3rd toes, and severe muscle hypotonia resulting in incapacity to stand without support. Consistent with a causative role for KIAA1109 loss-of-function/hypomorphic variants in this syndrome, knockdowns of the zebrafish orthologous gene resulted in embryos with hydrocephaly and abnormally curved notochords and overall body shape, whereas published knockouts of the fruit fly and mouse orthologous genes resulted in lethality or severe neurological defects reminiscent of the probands’ features.

Keywords: brain malformations, clubfoot, arthrogryposis, whole-exome sequencing, hydrocephaly, cerebellar hypoplasia

Introduction

The advent of high-throughput sequencing led to the delineation of multiple syndromes. Neurological genetic diseases are the main class of these Mendelian disorders1 with, for example, approximately 700 different genes confidently associated with intellectual disability (ID) and developmental delay notwithstanding that about 50% of yet unexplained ID-affected case subjects are predicted to have a genetic basis in genes remaining to be discovered.2, 3 Neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by brain malformations represent an important group among these unexplained conditions and are likely associated with mutations in genes implicated in cortical or cerebellar development. They can be classified into four main categories depending on the origin of the defect.4 First are disorders due to abnormal proliferation of neuronal and glial cells including brain under-growth (microcephaly) or overgrowth (megalencephaly). Second are neuronal migration disorders that include: (1) lissencephaly, i.e., the absence or decrease of gyration responsible for a smooth brain; (2) cobblestone cortical malformations; and (3) neuronal heterotopia, i.e., the abnormal localization of a neuronal population. Third are pathologies characterized by malformations caused by postmigrational abnormal cortical organization, mainly polymicrogyria, i.e., the increase of small gyration. The last category regroups malformations of the mid-hindbrain with early anteroposterior and dorsoventral patterning defects. This phenotypic heterogeneity is paralleled by molecular heterogeneity as more than 100 genes have been implicated to date.4, 5, 6, 7 The causative genes can be arranged into specific biological pathways (for instance synapse structure, cellular growth regulation, apoptosis, cell-fate specification, actin cytoskeleton, and microtubule assembly) that do not necessarily correlate with the type of malformations described above, as emerging evidence suggests that brain disorders are far more heterogeneous than the classification suggests.4, 8

We report, through description of 19 affected individuals, an autosomal-recessive brain malformation disorder with arthrogryposis caused by variants within KIAA1109 (MIM: 611565).

Material and Methods

Enrollment

Families were recruited in Lithuania, the United Kingdom, France, Saudi Arabia, the USA, and Singapore. The institutional review boards of the Vilnius University Faculty of Medicine, NHS Foundation Trust, Hôpitaux Universitaires de Strasbourg, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, “Hospices Civils de Lyon,” and KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital approved this study. Participants were enrolled after written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians. The clinical evaluation included medical history interviews, a physical examination, medical imaging as appropriate, and review of medical records.

Exome Sequencing and Analysis

To uncover genetic variants associated with the phenotypes of the two affected members of the Lithuanian (LT) family, we sequenced their exomes and that of their parents, as described.9 DNA libraries were prepared from leukocytes by standard procedures. Exomes were captured and sequenced using different platforms as specified below to reach 50- to 120-fold coverage on average. Variants were filtered based on inheritance patterns including autosomal recessive, X-linked, and de novo/autosomal dominant. Variants with MAF < 0.05% in control cohorts (dbSNP, the 1000 Genome Project, NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project, the ExAC, and our in-house databases) and predicted to be deleterious by SIFT,10 PolyPhen-2,11 and/or UMD predictor12 were prioritized. This exome analysis singled out compound heterozygote variants in KIAA1109 as possibly causative in both affected siblings, prompting us to look for other individuals with overlapping phenotypes and variants in the same gene through GeneMatcher, the DDD portal, and clinical genetics meetings. These searches led to the identification of a total of 17 additional affected individuals.

In the Algerian (AL) family, exome sequencing was performed by the Centre National de Génotypage (CNG, Evry, France), Institut de Génomique, CEA. Exomes were captured with Human All Exon v5; 50 Mb (Agilent Technologies) and sequenced on a HiSeq2500 platform (Illumina) as paired-end 100 bp reads. For the Saudi Arabian (SA1–SA3) families, exome capture and sequencing was performed in conjunction with autozygome analysis as previously described.13 For the family from Singapore (SG), exome capture, sequencing, and variant calling and analysis were performed as described.14 For the two families from Tunisia (TU1 and TU2), exome sequencing was performed on a NextSeq500 (Illumina) after SeqCapEZ MedExome Library preparation and analyzed with BWA and GATK HaplotypeCaller. Variants with MAF < 0.1% in ExAC database and predicted to be deleterious by SIFT,10 PolyPhen-2,11 and Mutation Taster15 were prioritized. The UK family’s exome capture and sequencing was performed as previously described.16 For the US family, exome capture, sequencing, and variant calling and analysis were performed as described.16, 17 The breakpoints of the paternally inherited deletion were determined by whole-genome sequencing.

Breakpoint Mapping by Whole-Genome Sequencing

100 ng of genomic DNA were sheared using Covaris with a target fragment size of 500 bp. The sequencing library was prepared using Tru-Seq DNA PCR-free Sample Prep Kit (Illumina) and 100-bp paired-end reads sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 platform (Illumina). The PCR-free kit was used to prepare the library in order to avoid PCR duplicates. Sequence-control, software real-time analysis, and bcl2fastq conversion software v.1.8.4 (Illumina) were used for image analysis, base calling, and demultiplexing. Purity-filtered reads were adapters- and quality-trimmed with FastqMcf. v.1.1.2 and aligned to the human_g1k_v37_decoy genome using BWA-MEM (v.0.7.1018). PCR duplicates were marked using Picard tools (v.2.2.1). We obtained a sequence yield of 11.4 Gb of aligned bases with a 3.6× mean coverage. Aligned reads within the KIAA1109 locus were visualized and evaluated using Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) in search of chimeric inserts. We identified a single pair of paired-ends reads mapping unequivocally 8,971 bp apart within KIAA1109 allowing us to map the paternally inherited deletion of the US proband breakpoints within exon 68 and intron 72. The breakpoints were then finely mapped with Sanger sequencing to coordinates chr4:123254885 and chr4:123263438 (hg19) (Figure S1).

Zebrafish Manipulations, CRISPR/Cas9 Editing, and Design of Morpholinos

Zebrafish animal experimentation was approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation of the Geneva University Medical School and the Canton of Geneva Animal Experimentation Veterinary authority. Wild-type TU (Tübingen) zebrafish were maintained in standard conditions (26°C–28°C, water conductivity at 500 μS [pH 7.5]). Embryos obtained by natural matings were staged according to morphology/age.

Zebrafish kiaa1109 mutant lines were developed using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing. Using the ZiFiT online tool,19 we identified three suitable 20-nucleotide sites upstream of protospacer adjacent motifs (PAM) for S. pyogenes Cas9 and targeting kiaa1109 exons 1, 4, and 7 (numbering according to GenBank: NM_001145584.1). Annealed oligonucleotides carrying the 20-nucleotide target sequence were ligated into pDR274 (Addgene plasmid # 42250), and clones verified by Sanger sequencing, linearized, and used for in vitro transcription of single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) using the MEGAshortscript T7 Transcription Kit (ThermoFisher). sgRNAs were mixed with recombinant Cas9 nuclease (PNA Bio), Danieau buffer, and phenol red as a tracer, and approximately 1 nL injected into early zebrafish embryos. Each injection contained 0.25 ng of sgRNA and 0.5 ng of Cas9 per nL. Evidence for genome editing was assessed qualitatively by PCR amplification around the target sites in each exon in injected embryo lysates. Heterogeneous PCR products, consistent with mosaic editing, was seen as smeared bands by gel electrophoresis, compared to uninjected embryos (not shown). Injected fish embryos were raised to adulthood and screened for their ability to transmit mutant kiaa1109 alleles by out-crossing and PCR genotyping. PCR products were cloned with pCRII TOPO (ThermoFisher) to separate alleles, and colony PCRs were sequenced to detect germline transmission of potential kiaa1109 frameshift alleles. Out-crossed F1 embryos were raised to adulthood for mutations detected in exon 1, 4, and 7, as separate lines. F1 adult fish were tail-clipped, targeted exons were amplified by PCR, and PCR products were cloned to pCRII TOPO (ThermoFisher) to identify specific kiaa1109 mutant alleles in heterozygosity by colony PCR and DNA sequencing. Heterozygous F1 fishes carrying the same kiaa1109 mutation were then in-crossed to assess embryonic survival and phenotype in homozygosity. kiaa1109 genotyping for embryos from these crosses was made using PCR, amplifying the target exon regions. Products from wild-type, heterozygous, or homozygous mutant amplicons were distinguished by gel electrophoresis. Details of the sgRNA target sites, representative mutant allele sequencing chromatograms, and predicted frameshifts for the three kiaa1109 mutant lines described are given in Figures S2 and S3.

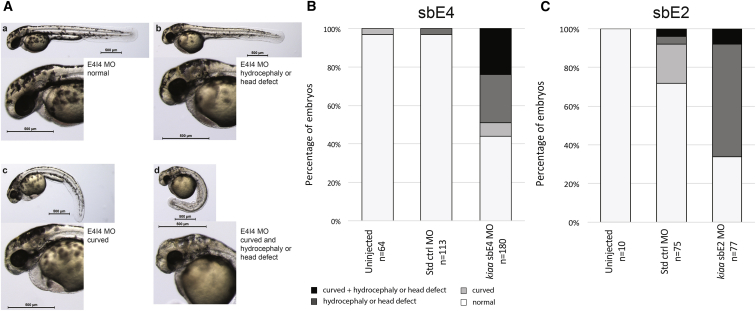

To knock down kiaa1109 (GenBank: NM_001145584.1) in zebrafish, we designed two non-overlapping splice-blocking MOs (morpholinos) targeting pre-mRNA: (1) sbE4MO- 5′-TGTTCTGTTTTTGCACTGACCATGT-3′ and (2) sbE2MO- 5′-CAACATTGAGACAGACTCACCGATG-3′ (Gene Tools) that target the exon 4/intron 4 and exon 2/intron 2 boundaries, respectively. The standard Ctrl-MO (5′-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3′) (Gene Tools) without any targets in the zebrafish genome was used for mock injections. MOs were dissolved in nuclease-free water and their concentrations determined by NanoDrop. The fish were injected at 1- to 2-cell stages (1–2 nL) using phenol red as a tracer in Danieau buffer. The following amounts of MO: 3.35 and 6.7 ng of sbE4MO; 5.6, 11.3, 16.9, and 22.3 ng of sbE2MO and the equivalent of Ctrl-MO for the higher doses were injected into wild-type zebrafish embryos, respectively. Uninjected, standard control MO, and kiaa1109 MO-injected embryos were collected at 2 dpf and total RNAs were isolated using standard Trizol protocol (Invitrogen). 1 μg of total RNA from each sample was used to synthesize cDNA with the Superscript III kit with Oligo d(T) primers (Invitrogen). Dilutions 1/20 of cDNA were used for standard PCR reactions (JumpStart RED Taq ReadyMix, Sigma-Aldrich). Basic quantifications of agarose gels were performed with ImageQuant TL software (GE Healthcare). We assessed embryos for morphological changes at 2 days post-fertilization. We grouped the embryos into four classes by morphology: normal embryos, embryos with clear midbrain and/or hindbrain ventricle swelling, curved embryos, and embryos with both phenotypes. The degree of hydrocephaly was not measured; hydrocephaly was assessed by clear deviation from the normal embryo morphology (see Results). Curved embryos showed caudal axis curvature. They were clearly distinguishable from the straight anterior-posterior axis of normal 2-day-old embryos (see Results). The most severely affected embryos had a combination of hydrocephaly and caudal axis curvature (see Results).

Results

We first identified compound heterozygous missense variants in KIAA1109 in a Lithuanian family with two affected siblings (LT.II.1 and LT.II.2) presenting with a constellation of severe global developmental delay, cerebral parenchymal rarefaction and ventriculomegaly (observed at 20 months of age), plagiocephaly, paretic position of hands and feet at birth, early-onset epilepsy, muscle hypotonia, stereotypical movements, hypermetropia, and lack of walking function (Table 1, Figure 1). As a homozygous stop-gain allele in this gene was suspected to cause a syndromic neurological disorder in a fetus (described in more details in this manuscript as fetus SA1.II.1) with cerebellar malformations, hydrocephalus, micrognathia, club feet, arthrogryposis with flexed deformity, pleural effusion, and death 1 hr after birth,13 we hypothesized that KIAA1109 variants cause an autosomal-recessive (AR) brain development disorder with arthrogryposis.

Table 1.

Overlapping Clinical Features of Individuals with KIAA1109 Variants

| Family # | Individual # | Gender, Age | Ethnicity | Gene Mutations | ID | Mutation Coordinates (GRCh37/hg19) | Cerebral Anomalies (Pre/Post-natal Images) and Pathological Findings | Head and Face | Eyes | Mouth | Joints | Limbs | Gastro-intestinal | Urogenital | Heart | Muscles | Behavior | Other Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LT | LT.II.1 (brother) | male, 13 yo | Lithuanian | compound heterozygote | severe, global developmental delay, no language, cannot stand or walk without support | Chr4:123160823; c.3986A>C, Chr4:123170727; c.5599G>A | post-natal brain MRI: small posterior fossa arachnoid cyst, discrete vermian atrophy, slight increase of the fluid-filled retro and infra-cerebellar space and mild enlargement of subarachnoid spaces of frontal regions. | plagiocephaly | hypermetropia, strabismus, astigmatism | delayed eruption of permanent teeth | mild contractures of large joints | syndactyly of 2nd and 3rd toes, hands and feet paresis at birth, talipes valgus | normal | scrotum hypoplasia | none | muscle hypotonia, atrophy | stereotypic movements, spontaneous paroxysms of laughter | early-onset epilepsy |

| LT | LT.II.2 (sister) | female, 7 yo | Lithuanian | compound heterozygote | severe, global developmental delay, no language, cannot sit or stand without support | Chr4:123160823; c.3986A>C, Chr4:123170727; c.5599G>A | post-natal brain MRI: discrete parenchymal rarefaction involving the frontal lobes | plagiocephaly | hypermetropia, strabismus, astigmatism | normal | mild contractures of large joints | paretic position of hands and feet in infancy, talipes valgus | chronic constipation | none | none | muscle hypotonia, atrophy | stereotypic movements | early onset epilepsy, dermatitis, psoriasis |

| UK | UK.II.1, DDD# 263241 | female, 11 yo | British | compound heterozygote with one de novo missense mutation | global developmental delay, mild to moderate learning disability | Chr4:123164200; c.4719G>A and Chr4:123171679; c.5873G>A | prenatal imaging (US and MRI): major microcephaly (HC -5 SD) with reduced white matter volume and mild ventriculomegaly | hypertelorism, slightly upslanting palpebral fissures | ocular motor apraxia, hypermetropia, strabismus | dental crowding, high palate | mild bilateral talipes managed by physiotherapy only; asymmetry of the thorax | syndactyly of 2nd and 3rd toes, 5th toe clinodacytly, hallux valgus | gastro-esophageal reflux | none | complex congenital heart disease (tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia) | none | poor concentration, immature behavior with minor self-harm (head-banging) when angry/frustrated | none |

| AL | AL.II.1 | male, termination of pregnancy at 21 weeks of amenorrhea | Algerian | homozygous missense mutation | not applicable | Chr4:123207807; c.9149C>A | prenatal US findings: triventricular ventriculomegaly and corpus callosum agenesis; neuropathological findings: absence of cortical lamination and diffuse migration anomalies within a thin parenchymal mantle, ventriculomegaly, and voluminous germinal matrix. Corpus callosum was not identified. Infra-tentorial space: hypoplasia of the pons with absence of the longitudinal and transversal fibers and dysplasia of the cerebellum characterized by lack of foliation and poorly identified vermis; narrowing of the aqueduct | hypertelorism, posteriorly rotated ears | bilateral cataract with crystalline fibers of variable size and orientation | retrognathism, big horizontalized mouth | arthrogryposis (flexed deformity of shoulders, elbow and hips, and bilateral adductus thumbs) | bilateral equinovarus foot | choanal atresia | scrotum hypoplasia | pericardial effusion | not available | not applicable | slight pleural effusion, peritoneal effusion, dilatation of lymph vessels in lung with lympho-hematopoietic elements |

| TU1 | TU1.II.1 | female, died at 3 days of age | Tunisian | homozygous missense mutation | not applicable | Chr4:123230520; c.10153G>C | prenatal imaging (US and MRI): cerebellar hypoplasia and brainstem dysgenesis (flat and elongated pons and slightly kinked brainstem with increased fluid filled retro-cerebellar spaces); severe parenchymal thinning with major lack of gyration (lissencephalic aspect) associated with voluminous germinal matrix protruding within moderate ventriculomegaly and absence of corpus callosum. Cephalic biometry was normal. | hypotelorism | none | deep palate | left club foot | long fingers | none | none | left heart hypoplasia | not available | not applicable | none |

| TU1 | TU1.II.4 | male, termination of pregnancy at 23 weeks | Tunisian | homozygous missense mutation | not applicable | Chr4:123230520; c.10153G>C | prenatal US findings: severe parenchymal thinning with lack of gyration associated with ventriculomegaly and corpus callosum agenesis. Neuropathological findings: complete corpus callosum agenesis, ventricular dilatation, severe cortical malformations with a reduced cortical plate, neuronal depletion, heterotopia within white matter, dysplasia of brainstem and cerebellum. | none | none | none | arthrogryposis (hip and shoulder contractures) | clenched hands, camptodactyly, club feet | none | none | none | not applicable | not applicable | none |

| TU2 | TU2.II.2 | female, died at 12 days of age | Tunisian | homozygous missense mutation | not applicable | Chr4:123230520; c.10153G>C | prenatal imaging (US and MRI): cerebellar hypoplasia and dysgenesis associated to severe brainstem dysgenesis characterized by flat and elongated pons and slightly kinked brainstem with increased fluid filled retro-cerebellar spaces. Corpus callosum was not identified. Supratentorial anomalies include severe parenchymal thinning associated with lissencephalic aspect as well as voluminous germinal matrix protruding within severe ventriculomegaly. | none | microphthalmia, blepharophimosis | none | club feet | club feet and hands | none | none | none | hypotonia | not applicable | narrow chest |

| SA1 | SA1.II.1, 13DG1900 | female, death at 1 hr after delivery | Saudi | homozygous nonsense mutation | not applicable | Chr4: 123128323; c.1557T>A | prenatal US findings: severe ventriculomegaly with supratentorial cerebral mantle thinning associated with cerebellar hypoplasia | small eyes, low-set ears | small eyes | micrognathia | severe arthrogryposis (fixed elbows, fixed bilateral talipes, bilateral overlapping fingers, bilateral clinodactyly) | bilateral club foot | not available | not available | not available | not available | not applicable | pleural effusion |

| SA2 | SA2.II.1, 15DG0595 | female, stillborn | Saudi | homozygous splice mutation | not applicable | Chr4:123252480; c.11250−1G>A | prenatal US findings: hydrocephalus, absent corpus callosum, hypoplastic cerebellum | not available | not available | not available | arthrogryposis multiplex | bilateral overlapping fingers, bilateral cleft feet, bilateral cleft toes, and bilateral sandal gaps | normal | bilaterally abnormal kidneys | not available | not available | not applicable | skeletal shortening, nuchal thickening |

| SA3 | SA3.II.1, 15DG1933 | female, stillborn | Saudi | homozygous nonsense mutation | not applicable | Chr4:123258092; c.12067G>T | prenatal US findings: hydrocephalus, hypoplastic cerebellum | not available | not available | not available | arthrogryposis | bilateral talipes | normal | normal | absent fetal heart | not available | not applicable | skin edema |

| US | US.II.3 | male, termination of pregnancy at 19 weeks | Caucasian | compound heterozygote | not applicable | Chr4:123113479; c.997dupA and Chr4: 123254885_123263438del; c.11567_12352delinsG | prenatal imaging (US and MRI): severe ventriculomegaly, thin cerebral parenchyma and cortical mantle associated with lissencephalic pattern, prominent germinal matrix, brain stem and vermian dysgenesis (kinked brain stem) and elongated pons; corpus callosum agenesis | low-set ears, webbed neck | normal | unremarkable | severe arthrogryposis with flexion contractures and pterygia, hyperflexed wrists, bilateral clinodactyly | bilateral talipes | normal | echogenic malrotated bowel without ascites, short penis with bulbous shaft | coarctation of the aorta | muscle atrophy | not applicable | low conus non-immune hydrops with scalp edema, cystic hygroma, anal atresia, bilateral pleural effusion |

| SG | SG.II.1 | male, died at 3 months of age | Chinese | compound heterozygote | not applicable | Chr4:123147970; c.2902C>T and Chr4:123159280; c.3611delA | post-natal MRI: supratentorial findings include both severe parenchymal (or cerebral mantle) thinning and smooth cortical surface, germinolytic cysts involving voluminous germinal matrix protruding within severe ventriculomegaly without any identification of corpus callosum. Infratentorial findings include severe cerebellar hypoplasia with severe brain-stem dysgenesis characterized by a kinking aspect. | macrocephaly; hypertelorism; posteriorly rotated ears; flattened nasal bridge | congenital cataract; microphthalmia | no structural anomalies | arthrogryposis (involving bilateral shoulders, elbows, wrists, hands, knees) | bilateral structural congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV) | ano-rectal malformation with recto-perianal fistula | no structural anomalies | small atrial septal defect/patent foramen ovale | hypotonia | not applicable | excess skin folds of neck |

| SG | SG.II.4 | male, died at 1 month of age | Chinese | compound heterozygote | not applicable | Chr4:123147970; c.2902C>T and Chr4:123159280; c.3611delA | post-natal MRI: supratentorial findings include both severe parenchymal (or cerebral mantle) thinning and smooth cortical surface, germinolytic cysts involving voluminous germinal matrix protruding within severe ventriculomegaly without any identification of corpus callosum. Infratentorial findings include severe cerebellar hypoplasia with severe brain-stem dysgenesis characterized by a kinking aspect | macrocephaly; hypertelorism; bilateral low-set ears, short nose; anteverted nares | congenital cataracts; microphthalmia | no structural anomalies | arthrogryposis (involving bilateral elbows, wrists, hands, knees, hips) | bilateral structural congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV) | normal | no structural anomalies | small to moderate fenestrated atrial septal defect | hypotonia | not applicable | webbed neck; inverted nipples |

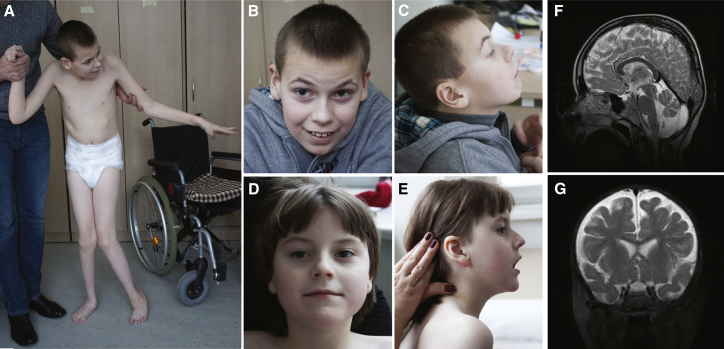

Figure 1.

Pictures and Brain MRI from Surviving Individuals

Front and side views of the LT affected brother LT.II.1 (A–C) and sister LT.II.2 (D, E) at the ages of 13 years and 7 years, respectively. Brain MRI images of affected individual LT.II.1 at age of 8 years showed small posterior fossa arachnoid cyst, discrete vermian atrophy, and slight increase of the fluid-filled retro and infra-cerebellar space (F). Brain MRI images of affected individual LT.II.2 at age of 1 year showed discrete parenchymal rarefaction involving mainly the frontal lobes (G).

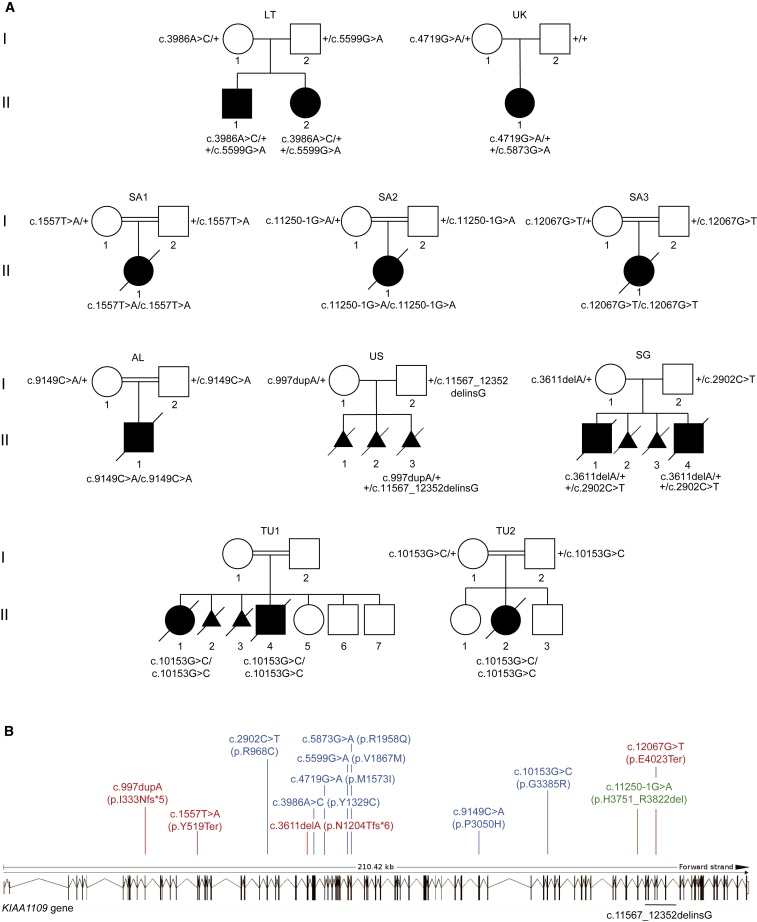

Our searches for more case subjects led to the identification of a total of 19 affected individuals from 10 families (including 6 undiagnosed miscarriages) recruited in Algeria (AL), Lithuania (LT), Saudi Arabia (SA1–SA3), Singapore (SG), Tunisia (TU1, TU2), the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States of America (US) (Figure 2A). Genetic variants associated with the complex phenotype of interest were uncovered through exome sequencing of the affected individuals and their healthy parents with the exception of SG.II.4. We found only one gene, KIAA1109, compliant with AR Mendelian expectations and bearing two putatively deleterious variants in all affected individuals. GENCODE20 catalogs in Ensembl 16 isoforms of KIAA1109; two encode the full-length 5,005-amino acids protein, six have no coding potentials, and the remaining eight isoforms encode protein of lengths varying from 164 to 1,674 amino acids. All the mutations reported in this manuscript affect the full-length GenBank: NP_056127 protein. Consistent with consanguineous unions, the affected members of families AL, TU1/TU2, SA1, SA2, and SA3 were homozygous for variants c.9149C>A (p.Pro3050His), for c.10153G>C (p.Gly3385Arg), for c.1557T>A (p.Tyr519Ter), for c.11250−1G>A (r.11250_11465del, p.His3751_Arg3822del), and for c.12067G>T (p.Glu4023Ter), respectively, whereas the affected individuals from LT, SG, UK, and US families were heterozygote for c.3986A>G (p.Tyr1329Cys) and c.5599G>A (p.Val1867Met), for c.2902C>T (p.Arg968Cys) and c.3611delA (p.Asn1204Thrfs∗6), for c.4719G>A (p.Met1573Ile) and the de novo c.5873G>A (p.Arg1958Gln), and for c.997dupA (p.Ile333Asnfs∗5) and the deletion g.123254885_123263438delinsG (c.11567_12352delinsG, p.Lys3856Argfs∗44), respectively (nomenclature according to GenBank: NM_015312.3, NP_056127.2; Figures 2A and 2B, Table S1). The fact that families TU1 and TU2 are not known to be related suggests a Tunisian founder effect of variant c.10153G>C (p.Gly3385Arg). Sanger sequencing in each family confirmed the anticipated segregation of the KIAA1109 variants, with the exception of family TU1 whose parents declined to be assessed. It also confirmed the genetic status of the SG.II.4 affected sibling (Figure 2A). All variants are either absent or encountered (as heterozygous variants) with a frequency lower than 1/10,000 in ExAC (v.0.3.1)21 (Table S1). The missense variants are predicted to be functionally damaging at least by two of the three PolyPhen-2,11 Provean,22 and SIFT10 predictors with the exception of the UK.II.1 variants predicted to be benign, neutral, and tolerated, respectively (Table S1). They might be under “compensated pathogenic deviation in human, a phenomenon that contributes to an unknown, but potentially large, number of false negatives to the evaluation of functional sites” as demonstrated in Jordan et al.23 Missense variants and CNVs are underrepresented compared to expectation in ExAC (missense Z score = 4.97; CNV Z score = 0.77) indicating that KIAA1109 is under constraint. The identification of 50 LoF variants compared to the 176.1 expected, while not significant with a pLI = 0.0, does not contradict this hypothesis. In agreement with a possible contributing role of bi-allelic KIAA1109 LoF variants to the phenotype of affected individuals SA1.II.1, SA2.II.1, SA3.II.1, and US.II.3, ExAC does not report homozygous LoF variants in KIAA1109. The splice variant c.11250−1G>A identified in fetus SA2.II.1 is predicted to abolish the consensus acceptor site of intron 66.24 A prediction validated by our RT-PCR experiments that showed a partial skipping of 216-nucleotides-long exon 67 in lymphoblastoid cell line of the affected SA2.II.1 fetus (Figure S4). The corresponding transcript would encode a protein lacking 72 amino acids. All missense variants identified in the AL, LT, SG, TU, and UK families affect highly conserved residues within evolutionary conserved region of the encoded protein (Figure S5).

Figure 2.

KIAA1109 Pedigrees and Variants

(A) Pedigrees of the ten families carrying KIAA1109 variants. The affected individuals of the Lithuanian (LT), Singaporean (SG), British (UK), and American (US) families are compound heterozygotes for rare variants, whereas the probands of the Algerian (AL), Saudi Arabian (SA1–SA3), and Tunisian (TU1, TU2) consanguineous families are homozygous for KIAA1109 variants.

(B) Distribution of variants along the schematically represented 86 exons of KIAA1109. Missense variants are depicted in blue, nonsense in red, and the splice site variant in green. The extent of the deletion identified in the proband of the US family is indicated in black below.

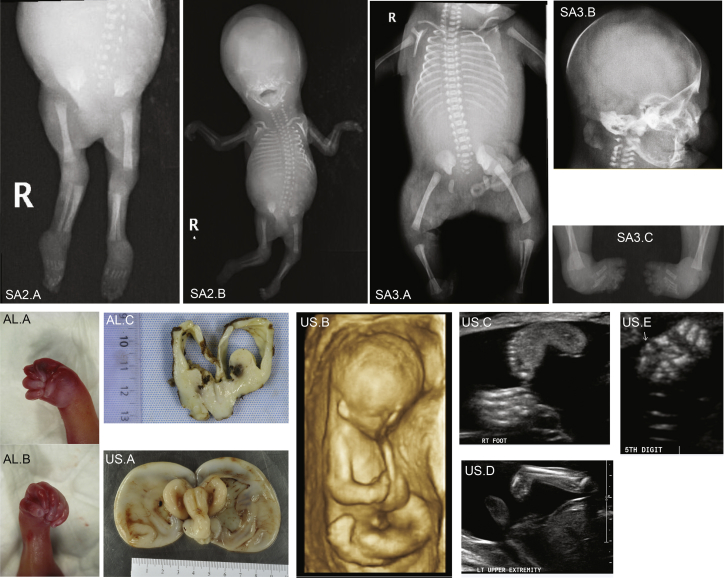

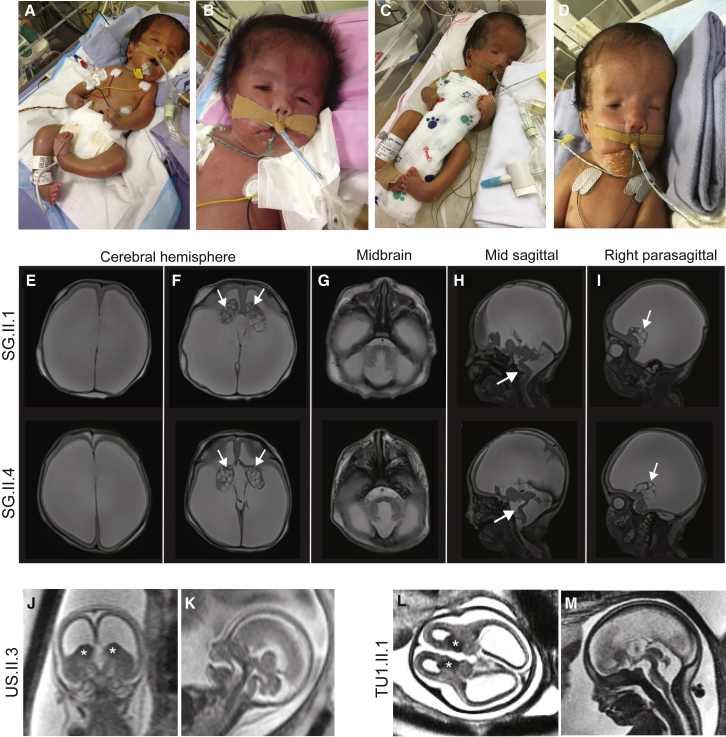

As exemplified by the LT.II.1 and LT.II.2 siblings and the SA1.II.1 proband, the phenotype of the 19 affected individuals ranges from global developmental delay with/without inability to stand to stillbirth. Many of the more severely affected case subjects harbor homozygous or compound heterozygote truncating alleles (families SA1–SA3 and US) (Table 1, Supplemental Note). While the phenotype of proband SA1.II.1 is summarized above, SA2.II.1 and SA3.II.1 stillborn fetuses shared hydrocephalus, cerebellar hypoplasia, arthrogryposis, and skeletal anomalies (Figures 3 and S6). Proband SA2.II.1 had bilateral overlapping fingers, apparent contractures of the hands and feet, and bilateral sandal gaps, along with shortened long bones and nuchal thickening. He also presented with absence of corpus callosum and abnormal kidneys. Proband SA3.II.1 showed skin edema, bilateral talipes, and arthrogryposis (Figure 3; Table 1; Supplemental Note). The US.II.3 stillborn fetus resulted from a 3rd pregnancy attempt of the couple (Figure 2A). The fetus demonstrated major central nervous anomalies including thin cerebral parenchyma with lissencephalic pattern, prominent germinal matrix, ventriculomegaly, brain stem vermian dysgenesis (kinked brain stem and elongated pons), and absence of corpus callosum, as well as closed spinal defect at L4-L5, associated with extra-central nervous anomalies including coarctation of the aorta, small omphalocele, echogenic bowel, hydrops, cystic hygroma, pleural effusion, possible anal atresia, low-set ears, short penis, clinodactyly, talipes, and abnormal posturing of the limbs (Figure 3). The SG family had four pregnancy attempts; two resulted in miscarriages (SG.II.2 and SG.II.3) and two in fetuses who did not pass the first semester (Figures 2A and 4). The SG.II.1 elder brother had minimal respiratory effort at birth and required immediate intubation and mechanical ventilation. He presented with macrocephaly, hypertelorism, posteriorly rotated ears, flattened nasal bridge, congenital cataract, and microphthalmia. He had generalized arthrogryposis and bilateral congenital talipes equinovarus. He also had hypotonia and an ano-rectal malformation with recto-perianal fistula (Figure 4). Brain MRI showed major cerebral parenchymal thinning with lissencephalic aspect, severe ventriculomegaly, absence of corpus callosum, and severe cerebellar and pontine hypoplasia (Figure 4). He passed away at 3 months of age from pneumonia and septic shock. The SG.II.4 younger sibling was remarkably similar to his elder with hypertelorism, bilateral low-set ears, short nose, anteverted nares, bilateral congenital cataract, microphthalmia, webbed neck, bilateral structural congenital talipes equinovarus, generalized arthrogryposis, and hypotonia. Brain MRI showed severe hydrocephalus with marked thinning of the cerebral parenchyma. The corpus callosum was absent, the cerebellum and brainstem were hypoplastic, and there was a pontomesencephalic kink. He remained ventilator dependent from birth and passed away at 1 month of age (Figure 4). The AL.II.1 fetus presented with an equally severe phenotype so the parents elected to terminate the pregnancy. He showed multiple brain malformations including hydrocephalus, vermis fusion, lamination defect of cerebellar cortex, and absence of the corpus callosum, combined with arthrogryposis with flexed deformity and bilateral adductus thumbs, diffuse effusion, and other clinical features (Figures 3 and S6; Table 1; Supplemental Note). Affected individuals and fetuses TU1.II.1, TU1.II.4, and TU2.II.2 had arthrogryposis and the same cerebral malformative pattern, associating cerebellar and brainstem dysgenesis, parenchymal thinning with major lack of gyration, corpus callosum agenesis, and hyperplastic germinal matrix protruding within ventriculomegaly. The severity of features of the AL.II.1 fetus, the SG.II.1 and SG.II.4 siblings, and the TU1.II.1, TU1.II.4, and TU2.II.2 Tunisian affected individuals and their resemblance with those observed in carriers of truncating variants suggest that the missense variants p.Pro3050His, p.Gly3385Arg, and p.Arg968Cys act as LoF or strong hypomorphs. Consistent with this hypothesis, the C>T transition in exon 24 of the latter variant is predicted to alter an exonic splicing enhancer site and thus proper splicing. More experiments are warranted to further demonstrate these assumptions.

Figure 3.

Ultrasound, X-Rays, and Autopsy Images of the SA2.II.1, SA3.II.1, AL.II.1, and US.II.3 Fetuses

X-ray images showing arthrogryposis of SA2.II.1 fetus (SA2.A and SA2.B).

X-ray images showing SA3.II.1 skeleton (SA3.A), head (SA3.B), and club feet (SA3.C).

Autopsy pictures from the AL.II.1 fetus showing right (AL.A) and left (AL.B) adductus thumbs of the fetus, and dilatation of cerebral ventricles with agenesis of corpus callosum (AL.C).

Autopsy image of the brain from US.II.3 fetus showing hydrocephalic brain with diaphanous pallium (US.A). The colliculi appear as single elongated ridges separated by a midline futter and the midline appears angulated on the brainstem, which is small as is the cerebellum. Antenatal ultrasound scan showed general arthrogryposis (US.B), one hyperflexed wrist (US.C), club feet (US.D), and bilateral clinodactyly of one hand (US.E).

Figure 4.

Pictures and Brain MRI Images of the SG.II.1 and SG.II.4 Babies and US.II.3 and TU1.II.1 Fetuses

(A–D) Photographs of SG.II.1 (A and B) and SG.II.4 (C and D) babies showing their whole bodies (A and C) and a close up of their faces (B and D).

(E–I) Brain MRI images of the elder brother SG.II.1 (top) and the younger brother SG.II.4 (bottom). Axial T2 weighted images showed severe ventriculomegaly, associated with severe thinning of the brain parenchyma (E, F). The brain parenchyma showed absence of normal gyral/sulcal pattern with smooth appearance in keeping with lissencephaly (E, F). Corpus callosum appeared to be absent (E, H). Note the prominent germinal matrix with germinolysis cysts (solid arrows) (F, I). The pons and cerebellum appeared hypoplastic with dilatation of the 4th ventricle (G, H) and Z shaped appearance of the brainstem (solid arrows) (H).

(J–M) Coronal (J), axial (L), and midsagittal (K, M) T2-weighed fetal prenatal MRI images of US.II.3 at 18.5 weeks of pregnancy (J and K) and TU1.II.1 at 28 weeks of pregnancy (L and M) demonstrating a similar imaging pattern including thin parenchyma (lissencephalic aspect), prominent germinal matrix marked by an asterisk, ventriculomegaly, and brain stem and vermian dysgenesis (kinked brain stem and elongated pons).

In summary, we observe a similar brain malformation pattern both prenatally—US.II.3 in (J) and (K), TU1.II.1 in (L) and (M), AL.II.1 (see text), TU1.II.4 (see text), and TU2.II.2 (see text)—and postnatally (SG.II.1 [E–I top] and SG.II.4 [E–I bottom]).

All case subjects compatible with life carry missense variants (Figure 2; Table S1; Supplemental Note). Whereas the two LT.II.1 and LT.II.2 Lithuanian siblings are briefly described above, the UK.II.1 British proband showed global developmental delay, microcephaly, absence of the pulmonary valve, tetralogy of Fallot and ventricular septal defect, ocular motor apraxia, hypermetropia, dental crowding, 5th toe clinodactyly, syndactyly of the 2nd and 3rd toe like the LT.II.1 elder sibling, hallux valgus, and pes planus (Supplemental Note).

In line with the clinical presentation of LoF affected individuals, ablation in fruit flies and mice of the KIAA1109 orthologs, tweek and Kiaa1109, respectively, resulted in lethality. Whereas Kiaa1109−/− mice engineered and phenotyped by the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium25, 26 exhibited complete penetrance of pre-weaning lethality, some rare homozygous tweek mutants survive to adulthood.27 These survivors presented with severe neurological defects such as seizures, inability to stand upright for long periods or walk, suggesting that tweek was involved in synaptic function.27 These results further support a causative role of LoF of KIAA1109 in the phenotypes observed in families AL, SA1–SA3, and US. Consistent with this hypothesis, KIAA1109 has higher expression in the pituitary, the cerebellum, and the cerebellar hemispheres according to GTex.28

To further assess the consequences of decreased KIAA1109 activity, we used both CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing and morpholinos (MO) technology in zebrafish. We generated three different stable lines with frameshift variants in exons 1, 4, and 7 of kiaa1109. Crosses of each heterozygote line with themselves suggest that these mutations are not lethal. To explain the discrepancy between these results and what was observed in mice and fruit flies, we profiled the transcriptome of homozygotes larvae. While we observed subtle differences between homozygous fish and their wild-type clutchmates, by and large we see no changes in expression of the different kiaa1109 exons (Table S2). Our results suggest that the expression of kiaa1109 isoforms containing only downstream exons encode proteins providing all the non-redundant functions of kiaa1109. More work is warranted to assess whether the engineered variants are inducing nonsense-mediated decay and whether there is any maternal contribution. In parallel, we knocked down kiaa1109 using two different non-overlapping morpholinos (MOs). While we are aware that unspecific effects have been reported when using MOs,29 we still favored this approach to mimic to a certain degree the situation observed in the LT.II.1 and LT.II.2 siblings and the UK.II.1 affected individual. Injection of early zebrafish embryos with 6.7 ng of sbE4MO resulted in a 50% reduction of the kiaa1109 transcripts through skipping of 65 nucleotides long exon 4 (Figure S7). 49% of morphants were hydrocephalic or presented with other head defects, whereas only 3% of the mock-injected fish showed such phenotypes (Figures 5A and 5B). The second MO, sbE2MO, acts through retention of 88-nucleotide-long intron 2 and decreases kiaa1109 levels by about 50% after injection of a large dose of 16.9 ng (Figure S7). Under such condition, about two-thirds (66%) of MO-sbE2 morphants were hydrocephalic or presented with other head defects compared to 8% of mock-injected fish affected at such dose (Figures 5A and 5C). Of note, rescue experiments of MO-injected zebrafish could not be performed due to the large size of the kiaa1109 transcript. In summary, knockdowns of the zebrafish KIAA1109 ortholog using two different MOs resulted in hydrocephalic animals reminiscent of probands’ features.

Figure 5.

kiaa1109 Knockdown in Zebrafish Results in Phenotypes Reminiscent of Probands’ Clinical Features

(A) Lateral views representing the four classes of observed phenotypes in 2 dpf TU zebrafish embryos injected with sbE4-MO (morpholino) targeting kiaa1109: from top left to bottom right, normal, hydrocephalic or other head defects, curved and curved with head defect.

(B) Results for uninjected embryos (left) and those injected with equivalent amounts of standard control MO (center) or kiaa1109 sbE4-MO (6.7 ng, right). Phenotyping and scoring were performed at 2 dpf in two independent experiments.

(C) Results for uninjected embryos (left) and those injected with equivalent amounts of standard control MO (center) or kiaa1109 sbE2-MO (16.9 ng, right). Phenotyping and scoring were performed at 2 dpf in two independent experiments.

Discussion

Data aggregation of exome sequencing from multiple laboratories allowed associating homozygous and compound heterozygote variants in KIAA1109 with a syndrome that we suggest naming Alkuraya-Kučinskas syndrome (AKS), as these clinicians first described affected individuals at the severe and mild ends of the phenotype, respectively. AKS combines severe brain malformations (13 affected individuals out of 13), in particular hydrocephaly/ventriculomegaly (11/13) and corpus callosum agenesis (8/13) with arthrogryposis/contractures (10/13) and/or talipes valgus/talipes equinovarus/club foot (12/13) and heart defects (6/13).

AKS presents multiple overlaps with Aase-Smith syndrome 1 (ASS1 [MIM: 147800]) characterized by arthrogryposis, hydrocephalus, Dandy-Walker malformation, talipes equinovarus, cardiac defects, and risks of stillbirth or premature death. However, the two described families with one father and two children affected30 and one mother and her affected daughter31 are suggestive of a dominant rather than a recessive mode of transmission. Consistent with the view that AKS and ASS1 have different etiologies, both ASS1-affected families presented individuals affected with cleft palate, a birth defect not present in the 13 KIAA1109 individuals described here, including those at the severe end of the phenotypic spectrum. Interestingly, we have identified by exome sequencing an individual with partially overlapping features carrying a single de novo variant in KIAA1109. Although we cannot exclude that a second variant is present outside of the open reading frame, we might, alternatively, be dealing (1) with a spurious association or (2) with another syndrome related to AKS and associated with single variants in KIAA1109, similar to the de novo and biallelic variation recently associated with mitochondrial dynamics pathologies.32 The high missense ExAC Z-score of KIAA1109 is compatible with such hypothesis. The identification of other similarly affected individuals will allow disentangling this conundrum.

The observed combination of intellectual disability, corpus callosum hypoplasia, hydrocephalus, and talipes equinovarus is also reminiscent of the constellation of features seen in the L1CAM-associated (neural cell adhesion molecule L1 [MIM: 308840]) HSAS (hydrocephalus due to congenital stenosis of aqueduct of sylvius [MIM: 307000]) and CRASH (corpus callosum hypoplasia, retardation, adducted thumbs, spastic paraplegia, and hydrocephalus [MIM: 303350]) syndromes. Whereas HSAS syndrome leads to neonatal or infant death, L1CAM variants survivors are described as affected by CRASH syndrome. Similarly, ten of the herein described AKS-affected case subjects did not survive past infancy (16 if accounting for undiagnosed miscarriages), whereas the living UK.II.1, LT.II.1, and LT.II.2 individuals presented other prominent features reported in CRASH syndrome, such as adducted thumbs, short stature, microcephaly, language impairment, and abnormalities of tone. L1CAM is a cell adhesion molecule that plays critical roles in neuronal migration and differentiation.33 Congenital joint contractures, limb deformities, hydrocephalus, corpus callosum agenesis, hypoplastic brainstem, cortical thinning, and high proportions of stillborn or neonatal death also are reminiscent of the PVHH (proliferative vasculopathy and hydranencephaly-hydrocephaly [MIM: 225790]) syndrome, a recessive disorder caused by variant in the transmembrane calcium transporter, FLVCR2 (feline leukemia virus subgroup C receptor 2 [MIM: 610865]).

The Drosophila ortholog of KIAA1109 named tweek is widely expressed but enriched in the brain lobes and in the ventral nerve cord.27 Neuronal phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P(2)] levels are critical in restricting synaptic growth via localization and activation of presynaptic Wiscott-Aldrich syndrome protein/WASP, a phenomenon dependent on tweek but not on bone morphogenetic protein signaling.34 The 5,005-amino-acid-long KIAA1109 protein is conserved from nematodes to vertebrates (Figure S8) in spite of a lack of recognizable domains, with the exception of a 22-residue amino-terminal transmembrane segment and a small central coiled-coil of 22 residues. It is described by specialists as an unconstrained peptide thought to adopt a definite conformation upon binding to its interactors.35 Consistent with this hypothesis, multiple high-throughput protein-protein interactions screens coupling near-endogenous expression levels with quantitative proteomics and mass spectrometry have identified human or mouse KIAA1109 interactors. For example, CTNNB1 (catenin beta-1), a protein associated with a dominant form of intellectual disability (MIM: 615075), interacts with two separate regions of KIAA1109.36 Another set of experiments showed high-confidence interactions with BUB3, DNAJB1, and PTPA, three proteins implicated in cell division.37 BUB3 participates to the spindle-assembly checkpoint signaling and the establishment of kinetochore-microtubule attachments. It inhibits the ubiquitin ligase activity of the anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C) by phosphorylating its activator CDC2. PTPA, one of four major Ser/Thr phosphatases, negatively controls cell growth and division. DNAJB1 (a.k.a. HSP40) interacts with HSP70 and stimulates its ATPase activity and its association with HIP. Interestingly, lower-confidence KIAA1109 protein interactors include BAG2 that competes with HIP for binding to the HSC70/HSP70 ATPase domain, as well as DRC1 and SMAD2. DRC1 (MIM: 615288) encodes a central component of the nexin-dynein complex that regulates the assembly of ciliary dynein and is associated with primary ciliary dyskinesia (MIM: 615294). SMAD2 (MIM: 601366) regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation through mediation of TGF-β signaling.

Conclusion

We propose that bi-allelic LoF and missense variants in KIAA1109 cause an autosomal-recessive brain malformation disorder with cerebral parenchymal underdevelopment ranging from major cerebral parenchymal thinning with lissencephalic aspect to moderate parenchymal rarefaction, severe to mild ventriculomegaly, and cerebellar hypoplasia with brainstem dysgenesis, associated with club foot and arthrogryposis. Severe cases are incompatible with life. Although further studies have to be engaged, our findings suggest that KIAA1109 is potentially involved in cell cycle control, particularly of the central nervous system.

Acknowledgments

We thank the affected individuals and their families for their contribution to this study. We are grateful to Keith Joung for reagents. This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (31003A_160203) to A.R., the Lithuanian-Swiss cooperation program to reduce economic and social disparities within the enlarged European Union (CH-3-ŠMM-0104, Unigene project) to V.K. and A.R., and King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology grant 13BIO-1113-20 to F.S.A. We also acknowledge the support of the Saudi Human Genome Program. The DDD Study presents independent research commissioned by the Health Innovation Challenge Fund (grant number HICF-1009-003), a parallel funding partnership between the Wellcome Trust and the Department of Health, and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (grant number WT098051). The study has UK Research Ethics Committee approval (10/H0305/83, granted by the Cambridge South REC, and GEN/284/12 granted by the Republic of Ireland REC). The research team acknowledges the support of the National Institute for Health Research, through the Comprehensive Clinical Research Network. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Published: December 28, 2017

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include Supplemental Note, eight figures, and two tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.12.002.

Contributor Information

Fowzan S. Alkuraya, Email: falkuraya@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Alexandre Reymond, Email: alexandre.reymond@unil.ch.

Accession Numbers

Alkuraya-Kucinskas syndrome as described in this paper has been assigned MIM: 617822.

Web Resources

1000 Genomes, http://browser.1000genomes.org/index.html

Burrows-Wheeler Aligner, http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/

Ensembl genome assembly GRCh37, http://grch37.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Info/Index

ExAC Browser, http://exac.broadinstitute.org/

ExomeDepth, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ExomeDepth/index.html

GTEx Portal, https://www.gtexportal.org/home/

NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) Exome Variant Server, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

OMIM, http://www.omim.org/

PolyPhen-2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/

SnpEff, http://snpeff.sourceforge.net/

Splicing Finder, http://www.umd.be/HSF3/HSF.html

Swiss PDB Viewer, https://spdbv.vital-it.ch/

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Yang Y., Muzny D.M., Reid J.G., Bainbridge M.N., Willis A., Ward P.A., Braxton A., Beuten J., Xia F., Niu Z. Clinical whole-exome sequencing for the diagnosis of mendelian disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:1502–1511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anazi S., Maddirevula S., Faqeih E., Alsedairy H., Alzahrani F., Shamseldin H.E., Patel N., Hashem M., Ibrahim N., Abdulwahab F. Clinical genomics expands the morbid genome of intellectual disability and offers a high diagnostic yield. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:615–624. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vissers L.E., Gilissen C., Veltman J.A. Genetic studies in intellectual disability and related disorders. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016;17:9–18. doi: 10.1038/nrg3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mirzaa G.M., Paciorkowski A.R. Introduction: Brain malformations. Am. J. Med. Genet. C. Semin. Med. Genet. 2014;166C:117–123. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato M. Genotype-phenotype correlation in neuronal migration disorders and cortical dysplasias. Front. Neurosci. 2015;9:181. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spalice A., Parisi P., Nicita F., Pizzardi G., Del Balzo F., Iannetti P. Neuronal migration disorders: clinical, neuroradiologic and genetics aspects. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:421–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verrotti A., Spalice A., Ursitti F., Papetti L., Mariani R., Castronovo A., Mastrangelo M., Iannetti P. New trends in neuronal migration disorders. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2010;14:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parrini E., Conti V., Dobyns W.B., Guerrini R. Genetic basis of brain malformations. Mol. Syndromol. 2016;7:220–233. doi: 10.1159/000448639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graziano C., Wischmeijer A., Pippucci T., Fusco C., Diquigiovanni C., Nõukas M., Sauk M., Kurg A., Rivieri F., Blau N. Syndromic intellectual disability: a new phenotype caused by an aromatic amino acid decarboxylase gene (DDC) variant. Gene. 2015;559:144–148. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng P.C., Henikoff S. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res. 2001;11:863–874. doi: 10.1101/gr.176601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adzhubei I.A., Schmidt S., Peshkin L., Ramensky V.E., Gerasimova A., Bork P., Kondrashov A.S., Sunyaev S.R. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salgado D., Desvignes J.P., Rai G., Blanchard A., Miltgen M., Pinard A., Lévy N., Collod-Béroud G., Béroud C. UMD-Predictor: a high-throughput sequencing compliant system for pathogenicity prediction of any human cDNA substitution. Hum. Mutat. 2016;37:439–446. doi: 10.1002/humu.22965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alazami A.M., Patel N., Shamseldin H.E., Anazi S., Al-Dosari M.S., Alzahrani F., Hijazi H., Alshammari M., Aldahmesh M.A., Salih M.A. Accelerating novel candidate gene discovery in neurogenetic disorders via whole-exome sequencing of prescreened multiplex consanguineous families. Cell Rep. 2015;10:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue S., Maluenda J., Marguet F., Shboul M., Quevarec L., Bonnard C., Ng A.Y., Tohari S., Tan T.T., Kong M.K. Loss-of-function mutations in LGI4, a secreted ligand involved in Schwann cell myelination, are responsible for arthrogryposis multiplex congenita. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;100:659–665. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarz J.M., Cooper D.N., Schuelke M., Seelow D. MutationTaster2: mutation prediction for the deep-sequencing age. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:361–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study Large-scale discovery of novel genetic causes of developmental disorders. Nature. 2015;519:223–228. doi: 10.1038/nature14135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue Y., Ankala A., Wilcox W.R., Hegde M.R. Solving the molecular diagnostic testing conundrum for Mendelian disorders in the era of next-generation sequencing: single-gene, gene panel, or exome/genome sequencing. Genet. Med. 2015;17:444–451. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sander J.D., Maeder M.L., Reyon D., Voytas D.F., Joung J.K., Dobbs D. ZiFiT (Zinc Finger Targeter): an updated zinc finger engineering tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W462–W468. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrow J., Frankish A., Gonzalez J.M., Tapanari E., Diekhans M., Kokocinski F., Aken B.L., Barrell D., Zadissa A., Searle S. GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for The ENCODE Project. Genome Res. 2012;22:1760–1774. doi: 10.1101/gr.135350.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lek M., Karczewski K.J., Minikel E.V., Samocha K.E., Banks E., Fennell T., O’Donnell-Luria A.H., Ware J.S., Hill A.J., Cummings B.B., Exome Aggregation Consortium Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi Y., Chan A.P. PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2745–2747. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jordan D.M., Frangakis S.G., Golzio C., Cassa C.A., Kurtzberg J., Davis E.E., Sunyaev S.R., Katsanis N., Task Force for Neonatal Genomics Identification of cis-suppression of human disease mutations by comparative genomics. Nature. 2015;524:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature14497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Desmet F.O., Hamroun D., Lalande M., Collod-Béroud G., Claustres M., Béroud C. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown S.D., Moore M.W. The International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium: past and future perspectives on mouse phenotyping. Mamm. Genome. 2012;23:632–640. doi: 10.1007/s00335-012-9427-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skarnes W.C., Rosen B., West A.P., Koutsourakis M., Bushell W., Iyer V., Mujica A.O., Thomas M., Harrow J., Cox T. A conditional knockout resource for the genome-wide study of mouse gene function. Nature. 2011;474:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verstreken P., Ohyama T., Haueter C., Habets R.L., Lin Y.Q., Swan L.E., Ly C.V., Venken K.J., De Camilli P., Bellen H.J. Tweek, an evolutionarily conserved protein, is required for synaptic vesicle recycling. Neuron. 2009;63:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melé M., Ferreira P.G., Reverter F., DeLuca D.S., Monlong J., Sammeth M., Young T.R., Goldmann J.M., Pervouchine D.D., Sullivan T.J., GTEx Consortium Human genomics. The human transcriptome across tissues and individuals. Science. 2015;348:660–665. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kok F.O., Shin M., Ni C.W., Gupta A., Grosse A.S., van Impel A., Kirchmaier B.C., Peterson-Maduro J., Kourkoulis G., Male I. Reverse genetic screening reveals poor correlation between morpholino-induced and mutant phenotypes in zebrafish. Dev. Cell. 2015;32:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aase J.M., Smith D.W. Dysmorphogenesis of joints, brain, and palate: a new dominantly inherited syndrome. J. Pediatr. 1968;73:606–609. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(68)80278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patton M.A., Sharma A., Winter R.M. The Aase-Smith syndrome. Clin. Genet. 1985;28:521–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harel T., Yoon W.H., Garone C., Gu S., Coban-Akdemir Z., Eldomery M.K., Posey J.E., Jhangiani S.N., Rosenfeld J.A., Cho M.T., Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics. University of Washington Center for Mendelian Genomics Recurrent de novo and biallelic variation of ATAD3A, encoding a mitochondrial membrane protein, results in distinct neurological syndromes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;99:831–845. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Itoh K., Fushiki S. The role of L1cam in murine corticogenesis, and the pathogenesis of hydrocephalus. Pathol. Int. 2015;65:58–66. doi: 10.1111/pin.12245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khuong T.M., Habets R.L., Slabbaert J.R., Verstreken P. WASP is activated by phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate to restrict synapse growth in a pathway parallel to bone morphogenetic protein signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:17379–17384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001794107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toth-Petroczy A., Palmedo P., Ingraham J., Hopf T.A., Berger B., Sander C., Marks D.S. Structured states of disordered proteins from genomic sequences. Cell. 2016;167:158–170.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyamoto-Sato E., Fujimori S., Ishizaka M., Hirai N., Masuoka K., Saito R., Ozawa Y., Hino K., Washio T., Tomita M. A comprehensive resource of interacting protein regions for refining human transcription factor networks. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hein M.Y., Hubner N.C., Poser I., Cox J., Nagaraj N., Toyoda Y., Gak I.A., Weisswange I., Mansfeld J., Buchholz F. A human interactome in three quantitative dimensions organized by stoichiometries and abundances. Cell. 2015;163:712–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.