Abstract

Objective

There is considerable evidence that college attainment is associated with family background and cognitive and non-cognitive skills. Behavioral genetic methods are used to determine whether the family background effect is mediated through cognitive and non-cognitive skill development.

Method

We analyze data from two longitudinal behavioral genetic studies, the Minnesota Twin Family Study, consisting of 1382 pairs of like-sex twins and their parents, and the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study, consisting of 409 adoptive and 208 non-adoptive families with two offspring and their rearing parents.

Results

Cognitive ability, non-cognitive skills, and family background are all associated with offspring college attainment. Biometric analysis show that the intergenerational transmission of college attainment owes to both genetic and shared environmental factors. The shared environmental influence was not due to highly educated parents fostering non-cognitive skill development in their children and there was limited evidence that they foster cognitive skill development.

Conclusions

The environmental transmission of educational attainment does not appear to be a consequence of highly-educated parents fostering cognitive and non-cognitive skill development. Alternative mechanisms are needed to explain the strong shared environmental influence on college attainment. Possibilities include academic expectations, social network effects, and the economic benefits of having wealthy parents.

Introduction

The Familial Aggregation of College Attainment

A four-year college degree has long been considered a ticket to economic and social success. Indeed, the Obama administration has identified increasing the rate of college education as a key factor in addressing growing levels of income inequality within the United States, and for good reason. As compared to individuals with only a high school education, those with a college degree are more likely to be employed and to earn a higher wage (Harmon & Walker, 1995). The benefits associated with a college education are, moreover, not limited to economic outcomes. Individuals with a college degree are more likely than those without a degree to report good health (Gross, Jobst, Jungbauer-Gans, & Schwarze, 2011), to be engaged citizens in their communities (Dee, 2004) and to live longer (Eide & Showalter, 2011); they are also less likely to smoke (de Walque, 2007) or be incarcerated (Lochner & Moretti, 2004). Although whether a college education is directly responsible for these benefits is open to question (Heckman & Vytlacil, 2001), the many factors associated with a college education have contributed to the perceived value of, and consequently the desire to achieve, a four-year college degree. Identifying and characterizing the factors that contribute to the attainment of a college degree will aid efforts aimed at increasing college graduation rates. Here we focus on two broad domains of influences: family background and individual-level skills.1

Perhaps the most widely studied predictor of completing a college degree is a family history of college attainment. Individuals who have one or more parents with a college degree are much more likely to complete college themselves than are individuals with parents who did not graduate from college. In their review of research on familial aggregation for educational attainment in 42 countries, Hertz et al. (Hertz et al., 2007) reported that the parent-offspring correlation for educational attainment has been stable for 50 years and ranged from approximately .30 to .50 in developed countries. The comparable sibling correlations were also stable over time and a bit higher than the parent-offspring correlations, generally ranging from about .40 to .60.

Biometric Studies of Educational Attainment

While there is no question that educational attainment aggregates in families, the meaning of this aggregation has been the subject of debate (Björklund & Salvanes, 2011). There are several issues, all informed by behavioral genetic research. First, the mere observation that parents with a college education are more likely than parents without a college degree to have children who also complete college cannot tell us whether familial transmission arises through genetic mechanisms, environmental mechanisms, or both. Biometrical methods seek to characterize the nature of genetic and environmental influences by distinguishing three major contributors to phenotypic variance: additive genetic (i.e., heritability), shared environmental (i.e., corresponding to the effects of environmental factors shared by reared-together relatives and thus a source of their behavioral similarity), and non-shared environmental (i.e., corresponding to the effects of environmental factors not shared by reared-together relatives and thus a source of their behavioral differences.) All three factors appear to make a substantial contribution to individual differences in educational attainment. In a recent meta-analysis of 21 different twin studies of educational attainment, Branigan et al.(2013) reported that the variance in educational attainment could be apportioned as 43% to additive genetic effects, 39% to shared environmental effects, and 18% to non-shared environmental effects. Adoption studies have constructively replicated the finding that additive genetic and shared environmental factors contribute roughly equally to the familial transmission of educational attainment. In a sample of 2125 Swedish adult adoptees, for example, Björklund et al.(2006) reported that the educational attainment of adopted adults was significantly and similarly related to the educational attainment of both their biological and adopted parents.

The finding of a strong shared environmental influence distinguishes educational attainment from most other behavioral phenotypes where shared environmental contributions have been consistently found to be either trivial or non-existent (Turkheimer, 2000). It has been suggested that the relative magnitudes of the genetic and shared environmental contributions to educational attainment can tell us something about equity in educational opportunity (Guo & Stearns, 2002). That is, heritability indexes the degree to which an individual's genetically influenced talents are phenotypically expressed, so it has been suggested that a high heritability indicates that individuals are able to fully realize their genetic potential. Alternatively, differences in educational outcomes that are a consequence of differences in family circumstances contribute to the shared environmental component of variance, a large value of which would consequently imply that family background contributes to unequal access to educational opportunities. The combination of a relatively (i.e., as compared to other behavioral traits) low value of heritability with an unexpectedly high value for the shared environmental contribution to educational attainment led Nielsen and Roos (2015, p. 1) to conclude that American society is characterized by “a high level of inequality of opportunity for educational attainment.”

The notion that biometric estimates could be used to evaluate public policy is certainly thought-provoking, although it did not originate with research on social inequality (e.g., Boardman, 2009). Indeed, in their bioecological model, Brofenbrenner and Ceci (1994) concluded that “heritability coefficients provide the best scientific tool presently available for assessing the extent to which particular environments and psychological processes foster or impede the actualization of individual differences in genetic potential for effective development (p. 570). Nonetheless, an educational policy that affords higher education only to those with blue eyes would result in high heritability estimates, although it is clearly not equitable. High heritability might be considered an indicator of equality of opportunity, but only if it is the result of genetically-influenced traits that foster academic success. Alternatively, although a high shared environmental contribution implies that families differ in their ability to create educational opportunities for their children, how we judge that contribution might depend on exactly what it is that families do to create those educational opportunities. A strong shared environmental contribution that was a consequence of only wealthy families being able to afford the high cost of higher education in the US would clearly indicate unfair access to opportunity (Kahlenberg, 2008). Alternatively, families differing in their ability to foster the development of the academic skills their children need to succeed in college might be seen as a more tolerable form of family influence than merely buying their way into college.

The Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Skills Underlying Educational Attainment

One major hypothesis about the nature of the parental influence on educational attainment centers on the activities college-educated parents engage in that might foster the development of academic skills in their children (Harding, Morris, & Hughes, 2015). College educated parents have been hypothesized to improve their children's cognitive skills by: exposing them to a broad and rich vocabulary (Hart & Risley, 1995); by providing an intellectually stimulating home environment (Suizzo & Stapleton, 2007); and by actively assisting them with their schoolwork (Kohl, Lengua, & McMahon, 2000). While the existing literature is consistent in showing that college-educated parents are more likely to engage their children intellectually than non-college-educated parents, much like research on the familial aggregation of educational attainment, this research fails to determine whether these associations are environmentally mediated or confounded by genetic factors.

Another limitation of research seeking to identify the mechanisms by which parents foster academic skill development in their children is that its focus has been overwhelmingly on cognitive skills. There is growing evidence that non-cognitive skills may be as important as, if not more important than, cognitive skills in attaining academic and occupational success (Heckman & Kautz, 2012). The non-cognitive domain most strongly and consistently associated with academic success is self-control and the related constructs of academic self-efficacy, persistence and effort (Richardson, Abraham, & Bond, 2012). Within the Five Factor Model of personality, academic performance has been most consistently associated with conscientiousness, and to a lesser degree agreeableness and openness to experience (Poropat, 2009). Conscientiousness is also highly correlated with grit (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009), the non-cognitive skill Duckworth (2007) has argued is key to academic success. Self-control is manifested not only in personality measures of grit and conscientiousness, but also in (the absence of) clinical symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity, perhaps helping to explain why externalizing psychopathology has been consistently associated with academic difficulties (Breslau, Michael, Nancy, & Kessler, 2008; Esch et al., 2014).

Emotional regulation is the second non-cognitive domain that has been linked to academic achievement (Ivcevic & Brackett, 2014). For example, the experience of negative emotion and emotional lability has been associated with poorer academic performance (Graziano, Reavis, Keane, & Calkins, 2007). Although much of the relevant research on emotional regulation is based on elementary-age children, the inability to control negative emotions such as aggression has also been associated with poor academic performance at the college level (Uludag, 2013). Unlike the extensive research literature documenting a positive association between parental socioeconomic status (SES) and offspring cognitive skills (e.g., Sirin, 2005; Strenze, 2007), only a few studies have investigated the relationship between family background and non-cognitive skills. Siles (2011) reported a modest negative association between parents' level of education and offspring aggression, while Cheng and Furnham (Cheng & Furnham, 2014) and Shanahan et al. (Shanahan, Bauldry, Roberts, Macmillan, & Russo, 2014) found generally weak correlations between parent education and offspring personality on the Big-five traits.

Summary and Current Study

The familial transmission of educational attainment contributes to current levels of social inequality. Both genetic and shared environmental factors influence individual differences in educational attainment, and as compared to other behavioral traits, the heritability of educational attainment is low while the shared environmental contribution is high. This pattern of biometric estimates has been interpreted as indicating that the US is characterized by high levels of inequality in educational opportunity. Nonetheless, the implications of biometric estimates for public policy depend on the mechanisms underlying heritable and shared environmental effects. Both cognitive and non-cognitive skills contribute to academic success, although how these contributions relate to genetic and environmental influences on educational attainment is poorly understood.

The present study used a behavioral genetic design to characterize the relationships among three major contributors to educational attainment: family background, cognitive skills, and non-cognitive skills. We used data from two large longitudinal family studies, one involving twins and their parents and the second involving adopted and non-adopted individuals and their parents, to address the following research questions:

Can we replicate the finding that both genetic and shared environmental factors contribute to the familial transmission of college attainment?

What is the contribution of cognitive and non-cognitive skills to college attainment?

Is the family background effect on college attainment mediated by highly educated parents fostering the development of cognitive and non-cognitive skills in their offspring?

Method

Participants: The Minnesota Center for Twin and Family Research

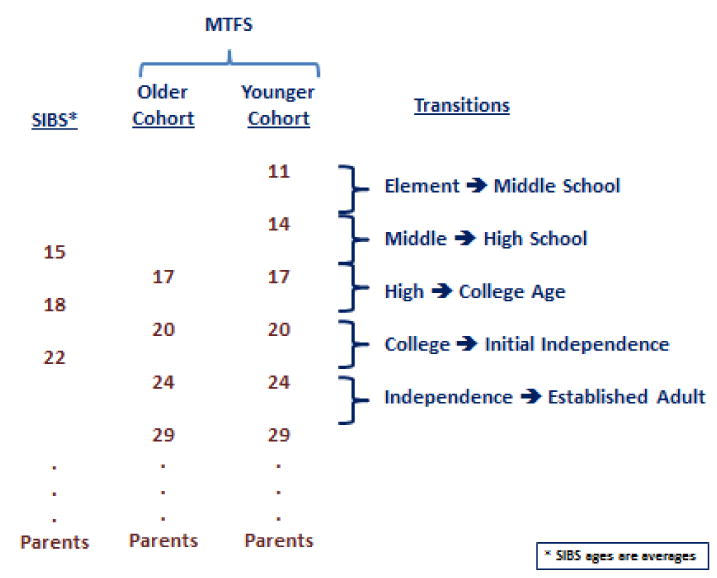

The Minnesota Center for Twin and Family Research (MCTFR) consists of a series of longitudinal studies that have followed individuals from adolescence through early adulthood. The basic sampling unit in all these studies is a four-member nuclear family consisting of a pair of adolescent offspring and their rearing parents. The offspring are distinguished by their relationship to each other, and include monozygotic (MZ) and like-sex dizygotic (DZ) twins, as well as adopted, non-adopted and mixed adopted/non-adopted sibling pairs. Across the various studies there are approximately 2500 families and 10,000 individuals who have participated in MCTFR research. Figure 1 provides an overview of the MCTFR longitudinal samples.

Figure 1.

Overview of the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS) and Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS) longitudinal designs. The ages given are the target assessment age (MTFS) or average assessment age (SIBS). Parents were typically assessed only one time.

The Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS)

The MTFS is a longitudinal study of 897 pairs of MZ and 485 pairs of like-sex DZ twins. Twins were ascertained from Minnesota state birth records and are broadly representative of that U.S. state. There are two cohorts in the MTFS and both cohorts have been re-assessed every 3-4 years through early adulthood. Twins in the younger cohort were initially assessed at a target age of 11, with subsequent assessments targeted at ages 14, 17, 20, 24 and 29. Twins in the older cohort were initially assessed at the target age of 17 and completed follow-up assessments at ages 20, 24 and 29. Rate of participation at follow-ups has ranged from 87% to 91%. Additional details concerning the MTFS sampling design and representativeness of the MTFS intake sample can be found in Iacono et al. (1999).

The Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS)

The SIBS is a longitudinal study of 409 adoptive and 208 non-adoptive families, each consisting of a pair of offspring and their rearing parents (we do not have information on the birth parents of the adopted offspring). Adoptive families were systematically ascertained through records of infant placements (average age at placement of 4.7 months, SD = 3.4 months) at three large adoption agencies in Minnesota. Non-adoptive families were ascertained through Minnesota birth records following the procedures used in the MTFS. In total, 1232 adolescents (692 adopted and 540 non-adopted) completed an intake SIBS assessment. Unlike the MTFS, it was not logistically possible to target specific ages for SIBS assessments. SIBS offspring were on average 14.9 (SD=1.9, range = 11-21) years old at intake; 18.3 (2.1, 14-25) at the first follow-up, and 22.4 (1.9, 19-28) at the second follow-up. Participation at both follow-ups exceeded 90%. Additional details concerning the SIBS sampling design can be found in McGue et al. (2007)

Assessments

At intake, four-member families completed an approximately five (SIBS) or eight (MTFS) hour assessment that covered multiple domains of functioning. Participants also completed several self-report questionnaires prior to their visit, which they returned completed at the time of their assessment. Except for the second SIBS follow-up, which was administered over the telephone, follow-up assessments were designed to be in-person although the small number of participants who had moved away from the state since their intake assessment completed the assessment over the telephone. Assessments overlapped extensively across the MTFS and SIBS and to the extent it was developmentally appropriate, across the different age assessments within each project. Here we highlight only those assessments of direct relevance to the research findings reported here. Of note, cognitive and non-cognitive skills were all assessed while participants were still in elementary or high school.

Cognitive Skill

The single cognitive skill measure was derived from the intake assessment in both the MTFS and SIBS studies and was based on an abbreviated version of either the WISC-R (for adolescents age 15 years and younger) or the WAIS-R (for adolescents age 16 and older). The abbreviated form consisted of four subtests, two verbal (Vocabulary and Information) and two performance (Block Design and Picture Arrangement), selected because performance on these subtests correlates .90 with overall IQ when all subtests are administered (Kaufman, 1990). Scores for the four subtests were prorated using standard procedures to obtain an IQ score.

Non-cognitive Skills

Personality was assessed with the Minnesota Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) (Tellegen & Waller, 2008). The MTFS age-17 assessment and the SIBS intake assessment for participants 16 years or older included all 11 primary-level MPQ scales; the SIBS intake assessment for participants age 15 years or younger, however, included only six MPQ scales (Well Being, Alienation, Aggression, Stress Reaction, Control, and Harm Avoidance). Although in Rustichini et al. (2015) we considered the predictive utility of the higher-order MPQ scales of Negative Emotionality, Positive Emotionality and Constraint in an analysis of academic achievement in the MTFS, those scales are not available at intake for all SIBS participants because they are a function of the scores on all 11 primary MPQ scales. Consequently, here we focus our analysis on three of the six common scales (Alienation, Aggression, and Control) selected because they relate to the constructs of self-control and emotional regulation hypothesized to be relevant to academic success. Each scale consisted of 18 items answered on a 4-point scale with an internal consistency, α, reliability that exceeds .80.

The final three non-cognitive skills were assessed identically at the MTFS age-17 and SIBS intake assessments. Two measures were based on maternal report of school-related behavior. The Academic Effort scale (α = .91) consists of eight items, each rated on a 4-point scale, covering effort (e.g., “Turns in homework on time”), and motivation (e.g., “Wants to earn good grades”) in school work. The Academic Problems scale (α = .77) consists of three items rated on a 4-point scale covering problems at school (e.g., “Easily distracted in class”). The final non-cognitive scale, Externalizing, consisted of the total number of symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorder (CD), and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) obtained through interview of the participating adolescent and his/her mother. Adolescents were interviewed with the revised version of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA-R) (Reich, 2000; Welner, Reich, Herjanic, Jung, & Amado, 1987), modified to ensure complete coverage of DSM-IV childhood disorders and covering the lifetime of the adolescent up through the time of the assessment. All questions asked of the adolescent were also asked of the mother, and the two reports for each symptom were combined using a “best-estimate” algorithm (Leckman, Scholomskas, Thompson, Belanger, & Weisman, 1982). Every interview was reviewed by at least two individuals with advanced clinical training, supervised by a Ph.D.-level clinical psychologist, who were blind to the diagnoses of other family members. This information was used to code, by consensus, every DSM-IV symptom and diagnosis. Analysis of interview data from 500 participants was used to determine the reliability (kappa coefficient) for our clinical assessments: .73 (ODD), .77 (ADHD), and .80 (CD). The Externalizing variable used in analyses reported here was computed as the sum of the symptoms of ADHD, ODD and CD.

A summary measure of non-cognitive skills was computed by summing the six individual non-cognitive measures after each measure had been standardized and those that were expected to be negatively associated with educational outcome reflected (i.e., Alienation, Aggression, Academic Problems, and Externalizing). The resulting composite was standardized, has an internal consistency reliability of .75, and correlated .997 with the first principal component of the non-cognitive measures.

Family Background

Following the recommendations of Braveman and colleagues (2005) we consider multiple aspects of family socioeconomic background. Three measures of family background, all based on parent self-report at the intake assessment, were used. First, mothers' and fathers' occupations were coded using the Hollingshead scale of occupational status, which ranges from 1 to 7 (Hollingshead, 1957). We reverse-scored the Hollingshead scale so that higher values represented higher status. Occupational status was coded as missing for those who did not work full-time, reported their occupation as “homemaker,” or reported that they were retired, disabled, or institutionalized. Parent Occupational Status was determined by taking the maximum of the mother's and father's status for each family. Mother and father' educational attainment was assessed on a five-point scale (1 = less than high school, 2 = high school, 3 = some post-secondary education, 4 = four-year college degree, 5 = graduate/professional degree) with Parent Education computed as the midparent average. Family Income was based on self-reported gross family income rated on a 1 (less than $10,000/year) to 13 (more than $80,000/year) scale. A summary family background measure was derived by summing the three individual measures after they had been standardized. The resulting composite was standardized to facilitate interpretation; it has an internal consistency reliability of .72 and correlated .999 with the first principal component of the three family background measures.

College Outcome

Educational attainment was determined at the age-24 and age-29 assessments in the MTFS and at the second follow-up assessment in SIBS. In the MTFS, we used as the primary outcome whether the participant had completed a four-year college degree. In SIBS, participants were between 19 and 28 years old at the second follow-up assessment, and although all SIBS participants would have had an opportunity to start college by that time not all of them would have had an opportunity to complete their college degree. That is, among the 587 SIBS participants age 19-22 at the second follow-up, 317 (54.0%) were currently attending college and only 37 (6.3%) had completed a four-year degree. In contrast, among the 538 SIBS participants age 23-28, 85 (15.8%) were attending college and 235 (43.7%) had completed a four-year degree. Consequently, our measure of educational attainment in SIBS is having completed or currently attending college at the second follow-up. In the U.S., a little more than 60% of those who start college complete a college degree within six years (Radford, Berkner, Wheeless, & Shepherd, 2010).

Analysis

Analysis included biometric analysis of the individual-level predictors and college outcome using Mx (Neale, Boker, Xie, & Maes, 2004). The goal in the biometric analyses was to determine the extent to which phenotypic variance on the various measures was associated with additive genetic influences (A), shared environmental influences (C, that is, the influence of those environmental factors that are shared by relatives who are reared together and thus a potential source of the phenotypic similarity), and non-shared environmental influences (E, that is, those environmental factors that are not shared by reared-together and thus are a source of their behavioral differences). We also investigated the relationship between the individual predictors and college attainment using logistic regression analysis. In all regression analyses, age at follow-up (i.e., when the college outcome was determined) and gender were included as covariates, and the clustering of observations by family taken into account using a mixed model approach. To facilitate interpretation of the regression results, individual-level and family background factors were standardized separately in the MTFS and the SIBS non-adopted and adopted samples.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics, reported separately by gender, for the MTFS and the non-adopted and adopted SIBS samples are given in Table 1. Although the methodology was not identical across the two studies, several general trends can be noted. First, males consistently score more poorly on the various non-cognitive indicators than females. That is, males showed higher levels of Alienation, Aggression, Academic Problems and Externalizing and lower levels of Control and Academic Effort as compared to females. On the Non-Cognitive composite, the standardized mean difference between males and females (95% confidence interval) was -.57 (-.73, -.41), -.70 (-1.06, -.34), and -.67 (-.98, -.35) in the MTFS, SIBS non-adopted, and SIBS adopted samples, respectively. There were no consistent gender differences on the Family Background measures, but males scored significantly albeit modestly higher than females in IQ. In any case, there is a consistent and moderate female advantage in college attainment. The odds ratio (OR) (95% confidence interval) was 1.7 (1.4, 2.1) for the association of gender with college completion in the MTFS and 1.6 (1.1, 2.3) and 1.8 (1.3, 2.5) with college attendance in the SIBS non-adopted and adopted samples, respectively.

Table 1. Comparison of men and women on predictor variables (mean (SD)) and college outcome (%) in the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS) and the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS).

| MTFS | SIBS – Non-Adopted | SIBS – Adopted | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Men | Women | d/OR (95% CI) |

Men | Women | d/OR (95% CI) |

Men | Women | d/OR (95% CI) |

| N | 1159 | 1304 | 221 | 266 | 276 | 362 | |||

| Intake Age | 17.8 (0.6) |

17.9 (0.7) |

-.15 (-.31, .01) |

14.9 (1.9) |

14.9 (1.9) |

.01 (-.35,.36) |

14.9 (1.7) |

15.1 (2.1) |

-.10 (-.42, .21) |

| Follow-up Age | 29.3 (1.1) |

29.2 (1.0) |

.10 (-0.6, .25) |

22.3 (1.8) |

22.2 (1.8) |

.06 (-.30, .41) |

22.4 (1.6) |

22.5 (2.0) |

-.05 (-.37, .26) |

| Cognitive: | |||||||||

| IQ | 104.3 (13.8) |

100.3 (14.2) |

.29 (.13, .44) |

112.5 (12.8) |

105.1 (12.6) |

.58 (.23, .94) |

108.7 (14.2) |

105.3 (13.6) |

.25 (-0.7, .56) |

| Non-Cognitive: | |||||||||

| Alienation | 35.9 (8.2) |

34.7 (8.9) |

.14 (-.02, .30) |

37.1 (9.8) |

34.1 (9.3) |

.31 (-.04, .67) |

36.6 (9.1) |

35.0 (9.6) |

.17 (-.14, .480 |

| Aggression | 41.7 (9.3) |

34.5 (8.9) |

.79 (.63, .95) |

43.3 10.80 |

34.8 (9.0) |

.86 (.51, 1.22) |

43.2 (10.0) |

35.6 (9.5) |

.78 (.47, 1.10) |

| Control | 46.7 (7.1) |

48.1 (7.7) |

-.19 (-.35, -.03) |

45.0 (8.6) |

48.0 (7.5) |

-.37 (-.73, -.02) |

44.6 (8.3) |

47.9 (8.9) |

-.38 (-.69, -.07) |

| Academic Effort | 25.6 (5.2) |

28.0 (4.2) |

-.52 (-.67, -.35) |

19.9 (3.7) |

21.4 (2.60 |

-.48 (-.83, -.12) |

19.4 (3.7) |

21.2 (3.1) |

-.53 (-.85, -.22) |

| Academic Problems | 5.6 (2.1) |

5.1 (2.0) |

.24 (.09, .40) |

10.7 (3.9) |

9.6 (3.5) |

.30 (-.06, .66) |

11.7 (4.3) |

9.9 (3.8) |

.45 (.13, .76) |

| Externalizing | 3.7 (3.7) |

2.1 (2.4) |

.52 (.36, .68) |

4.8 (5.6) |

2.6 (3.9) |

.46 (.11, .82) |

6.8 (6.4) |

3.9 (5.0) |

.51 (.20, .83) |

| Composite | -.30 (1.0) |

.27 (1.0) |

-.57 (-.73, -.41) |

-.24 (1.0) |

.40 (0.8) |

-.70 (-1.06,-.34) |

-.40 (.97) |

.24 (.95) |

-.67 (-.98, -.35) |

| Family Background: | |||||||||

| Family Income | 8.6 (3.2) |

9.0 (3.0) |

-.13 (-.29, .03) |

11.7 (1.9) |

11.3 (2.5) |

.18 (-.18,.53) |

11.7 (2.3) |

11.7 (2.2) |

-.03 (-.34, .29) |

| Parent Occupation Status | 4.7 (1.6) |

4.7 (1.6) |

-.03 (-.19, .13) |

5.3 (1.4) |

5.2 (1.5) |

0.07 (-.29, .43) |

5.8 (1.2) |

5.7 (1.3) |

.02 (-.29, .34) |

| Parent Education | 2.6 (0.9) |

2.7 (0.9) |

-.11 (-.27, .05) |

3.5 (0.8) |

3.5 (0.8) |

-.01 (-.37, .34) |

3.8 (0.7) |

3.8 (0.8) |

.01 (-.30,.33) |

| Composite | -.03 (1.0) |

.04 (1.0) |

-.07 (-.23, .09) |

-.17 (1.0) |

-.23 (1.0) |

.06 (-.30, .42) |

0.18 (0.9) |

0.20 (0.9) |

-.02 (-.34,.29) |

| Education Outcome: | |||||||||

| College | 38.9% | 52.3% | 1.73 (1.43,2.10) |

58.8% | 69.5% | 1.60 (1.10,2.32) |

47.8% | 62.7% | 1.83 (1.34,2.52) |

Note: d = standardized mean difference is reported for quantitative outcomes and was computed as the mean for men minus the mean for women divided by the pooled standard deviation; the odds ratio (OR) is reported for the college outcome variable and is scaled such that an OR > 1.0 reflects a higher frequency in women.

Familial Aggregation for College Attainment and Attendance

In the MTFS, the rate of completing a four-year college degree was greater among the twin offspring than their parents for both women (52% in twins versus 25% in mothers) and men (39% in twins versus 29% in fathers). The intergenerational increase in rate of college attainment and the higher rate of college completion in recent birth cohorts among women as compared to men is consistent with secular increases in educational attainment within the U.S. (United States Census Bureau, 2015). The overall high rate of college completion in the offspring generation reflects in part the higher rate of college completion in Minnesota than in most other U.S. states.

In Rustichini et al. (2015) we explored the intergenerational transmission of educational attainment in the MTFS; here we combine that analysis with an analysis of SIBS. Figure 2 summarizes the rate of completing a college degree by the age-29 assessment in the MTFS offspring as a function of the number of their parents with a college degree. There is strong familial aggregation for the attainment of a college degree. The OR (95% confidence interval) associated with one additional parent with a college degree in the logistic model was 4.2 (3.4, 5.1) (χ2 on 1 df= 181.7, p < .001).

Figure 2.

The association of college attainment with the number of rearing parents with a college degree. MTFS = Minnesota Twin Family Study, SIBS = Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study. College attainment is completion of a college degree by the age-29 assessment in the MTFS and either completion of a college degree or currently attending college by the second follow-up in SIBS. Error bars demarcate 95% confidence intervals.

To explore the factors contributing to individual differences in completing college, we estimated tetrachoric correlations for college completion among family members in the MTFS and then fit a biometric model to this data using Mx (Neale et al., 2004). The tetrachoric correlation (95% confidence interval) estimates were .83 (.78, .88) for MZ twins, .73 (.63, .81) for DZ twins, .46 (.40, .51) for mother-offspring, .50 (.46, .56) for father-offspring, and .69 (.63, .74) for mother-father. The large size of the tetrachoric correlations further document the strong familial aggregation that exists for college attainment; the greater MZ than DZ twin correlations implicates a contribution of genetic factors. Estimates from a biometric twin-family model that allowed for the effects of assortative mating were: 33% for additive genetic effects, 39% for shared environmental effects, 17% for non-shared environmental effects, and 12% for gene-environment covariance (estimable in this case because of information on the parents of the twins).

To further confirm the importance of shared environmental influences on educational attainment, we separately analyzed the adopted and non-adopted offspring samples from SIBS.2 Figure 2 gives the rate of college attainment, defined in SIBS as completing a college degree or currently attending college, in adopted and non-adopted offspring as a function of the number of their rearing parents who had a college degree. In the non-adopted sample, the association of parent college with offspring college attainment was moderate, OR = 2.6 (2.0, 3.3), and statistically significant (χ2 on 1 df= 14.5, p < .001). This association was also statistically significant in the adopted offspring sample (χ2 on 1 df= 14.5, p < .001), although in this case the parent effect was smaller in magnitude, OR=1.5 (1.2, 1.8). Nonetheless, because there is no genetic basis for parent-offspring resemblance in the adopted sample, this association provides evidence for a shared environmental effect. Further evidence that shared environmental influences are important for college attainment is provided by the adopted sibling tetrachoric correlation, which was .37 (.21, .51).

The Contribution of Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Skills and Family Background to College Attainment

College attainment was regressed separately onto each of the cognitive, non-cognitive and family background predictors in a logistic regression in which gender and age at follow-up were also included as covariates. To facilitate interpretation of the results, all predictors were standardized and ORs for predictors negatively associated with outcome (i.e., Alienation, Aggression, Academic Problems, and Externalizing) were reflected. The results of these analyses are reported separately in Table 2 for the MTFS, SIBS non-adopted, and SIBS adopted samples. The association between the individual predictors and college outcome varied significantly by gender in only one of 36 possible comparisons (i.e., 3 samples by 12 predictors). Alienation was somewhat more strongly associated with college completion in the female than in the male MTFS sample (χ2 on 1 df= 4.0, p =.04). Because one marginally significant result in 36 comparisons is about what is expected by chance and because the moderation effect on Alienation was not seen in the SIBS samples, we report ORs for the pooled male and female sample only in the table. In all three samples, IQ was significantly and moderately associated with educational outcome (ORs ranged from 1.9 to 2.1). The individual non-cognitive predictors were also all significantly associated with college attainment in all samples, with associations being strongest for Academic Effort and Academic Problems (ORs generally between 2.0 and 3.0) and weakest for the three MPQ personality scales (ORs between 1.3 and 1.9). Finally, each of the Family Background indicators was significantly associated with college attainment, although the magnitudes of these associations were notably weaker in the adopted as compared to non-adopted SIBS sample, a pattern we return to later.

Table 2. Association of college attainment with standardized cognitive, non-cognitive and family background predictors.

| Predictor | MTFS | SIBS – Non-Adopted | SIBS – Adopted | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||||

| Wald Statistic (1 df) |

OR (CI) |

Wald Statistic (1 df) |

OR (CI) |

Wald Statistic (1 df) |

OR (CI) |

Wald Statistic (1 df) |

OR (CI) |

Wald Statistic (1 df) |

OR (CI) |

Wald Statistic (1 df) |

OR (CI) |

|

| Cognitive: | ||||||||||||

| IQ | 183.3 p < .001 |

1.9 (1.7, 2.1) |

73.5 p < .001 |

1.6 (1.4, 1.8) |

32.7 p < .001 |

2.0 (1.6, 2.5) |

12.9 p < .001 |

1.6 (1.3, 2.1) |

60.9 p < .001 |

2.1 (1.8, 2.6) |

36.3 p < .001 |

1.9 (1.6, 2.4) |

| Non-Cognitive: | ||||||||||||

| Alienation* | 69.7 p < .001 |

1.4 (1.3,1.5) |

24.9 p < .001 |

1.7 (1.4, 2.1) |

20.3 p < .001 |

1.5 (1.2, 1.7) |

||||||

| Aggression* | 47.5 p < .001 |

1.3 (1.2,1.5) |

30.3 p < .001 |

1.8 (1.5, 2.2) |

17.5 p < .001 |

1.5 (1.2, 1.8) |

||||||

| Control | 70.8 p < .001 |

1.4 (1.3, .15) |

32.9 p < .001 |

1.9 (1.5, 2.4) |

33.9 p < .001 |

1.6 (1.4, 1.9) |

||||||

| Academic Effort | 165.9 p < .001 |

2.6 (2.2, 3.0) |

49.8 p < .001 |

2.4 (1.9, 3.0) |

70.9 p < .001 |

2.4 (2.0, 3.0) |

||||||

| Academic Problems* | 128.6 p < .001 |

1.9 (1.7, 2.1) |

62.7 p < .001 |

2.8 (2.2, 3.7) |

125.6 p < .001 |

3.1 (2.6, 3.8) |

||||||

| Externalizing* | 105.2 p < .001 |

1.6 (1.4, 1.7) |

38.1 p < .001 |

1.9 (1.6, 2.4) |

53.6 p < .001 |

2.0 (1.7, 2.4) |

||||||

| Composite | 208.8 p < .001 |

2.2 (2.0, 2.4) |

146.0 p < .001 |

2.1 (1.9, 2.4) |

68.3 p < .001 |

3.2 (2.5, 4.3) |

58.4 p < .001 |

3.1 (2.3, 4.2) |

119.1 p < .001 |

3.0 (2.4, 3.6) |

104.6 p < .001 |

2.9 (2.4, 3.5) |

| Background: | ||||||||||||

| Family Income | 105.1 p < .001 |

1.8 (1.6, 2.0) |

17.9 p < .001 |

1.6 (1.3, 2.1) |

13.5 p < .001 |

1.5 (1.2, 1.8) |

||||||

| Parent Occupation | 125.7 p < .001 |

1.9 (1.7, 2.1) |

25.6 p < .001 |

1.8 (1.4, 2.2) |

9.0 p = .03 |

1.4 (1.1, 1.7) |

||||||

| Parent Education | 212.6 p < .001 |

2.3 (2.1, 2.6) |

43.7 p < .001 |

2.1 (1.7, 2.7) |

6.0 p = .02 |

1.3 (1.1, 1.5) |

||||||

| Composite | 212.6 p < .001 |

2.3 (2.1, 2.6) |

146.5 p < .001 |

2.1 (1.9, 2.4) |

41.4 p < .001 |

2.0 (1.6, 2.5) |

24.7 p < .001 |

1.8 (1.4, 2.3) |

17.3 p < .001 |

1.5 (1.2, 1.8) |

17.2 p < .001 |

1.6 (1.3, 2.0) |

Note: All predictors were standardized in these analyses, which took into account gender and age at the relevant follow-up. College attainment was completion of a 4-year degree by the age-29 assessment in the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS) and completion of a 4-year degree or currently attending college at the time of the second follow-up in the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS).

Results for predictors negatively associated with college attainment have been reflected to facilitate comparisons

To facilitate comparison of findings across studies, we have plotted the ORs for IQ and the Non-Cognitive and Family Background composites from the three samples in Figure 3. Several patterns are evident. First, as previously noted, the association of IQ was quite consistent across the three samples even though college attainment was defined differently in the MTFS and SIBS samples. Second, the effect of the Non-Cognitive composite was greater in the two SIBS samples than in the MTFS sample, and in both SIBS samples the effect of the Non-Cognitive composite was greater than the effect of IQ. This pattern may be a consequence of how college attainment was defined differently in the two studies. Specifically, non-cognitive factors may be especially critical in gaining admission to college, with cognitive factors being relatively more important in completing college given admission. Finally, the association of the Family Background composite with college attainment was weakest in the adopted as compared to non-adopted SIBS sample (with the difference being marginally statistically significant; (χ2 on 1 df= 4.1, p =.04). In interpreting this difference, it is important to recognize that unlike in the MTFS and the non-adopted SIBS samples, where associations with family background factors potentially confound genetic with shared environmental effects, in the adopted SIBS sample there is no basis for genetic similarity so that these associations must be a consequence of environmental processes only.

Figure 3.

Univariate odds ratios for predicting college attainment from each composite measure. College attainment was completion of a 4-year degree by the age-29 assessment in the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS) and completion of a 4-year degree or currently attending college at the time of the second follow-up in the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS). Error bars demarcate 95% confidence intervals.

Also given in Table 2 are the results for regressing college attainment simultaneously on IQ and the two composites separately in the three samples. In these multivariate models, the effects of IQ and the two composites were all statistically significant in all three samples. Indeed, the ORs in the multivariate models were of a similar magnitude as the corresponding ORs in the univariate models, with the notable exception of IQ in the MTFS and non-adopted SIBS (but not the adopted SIBS) samples, for which the OR was slightly lower in the multivariate than in the corresponding univariate model. The multivariate analyses demonstrate that the three domains, cognitive and non-cognitive factors and family background, are independently associated with college attainment.

Biometric Analysis of the Individual-Level Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Factors

Twin and sibling correlations for the individual-level predictors are given in Table 3 (note that family background factors will be identical and so would be perfectly correlated for all twin and sibling pairs). For all eight individual-level factors, MZ twins were the most and adopted siblings the least similar, a pattern implicating genetic influences. Also given in the table are the standardized estimates (95% confidence intervals) for additive genetic, shared environmental, and non-shared environmental contributions to the phenotypic variance for each of the factors. As judged by the 95% confidence intervals, there is a statistically significant and moderate to large genetic influence on all of the eight factors; estimates of the non-shared environmental contribution are also all statistically significant and moderate and large in magnitude. In contrast, the shared environmental estimates are uniformly low and statistically significant for only two of the factors, IQ and Externalizing.

Table 3. Twin and non-adopted and adopted sibling correlations and biometric parameter estimates for cognitive and non-cognitive predictors and educational attainment.

| Variable | Correlation | Biometric Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MZ (N=813) |

DZ (N=446) |

Non-adopted Siblings (N=207) |

Adopted Siblings (N=404) |

Additive Genetic | Shared Environment | Non-Shared Environment |

||

| IQ | .78 | .54 | .33 | .17 | .61 (.54, .68) |

.17 (.10, .24) |

.22 (.20, .24) |

|

| Alienation | .45 | .29 | .17 | .09 | .36 (.25, .47) |

.08 (.00, .17) |

.56 (.51, .61) |

|

| Aggression | .49 | .16 | .34 | .12 | .40 (.29, .50) |

.08 (.00, .16) |

.52 (.47, .58) |

|

| Control | .38 | .11 | .16 | .02 | .37 (.28, .43) |

.00 (.00, .06) |

.63 (.57, .69) |

|

| Academic Effort | .82 | .37 | .15 | .12 | .83 (.77, .85) |

.00 (.00, .06) |

.17 (.15, .19) |

|

| Academic Problems | .81 | .37 | .16 | .00 | .82 (.78, .84) |

.00 (.00, .03) |

.18 (.16, .21) |

|

| Externalizing | .54 | .38 | .18 | .14 | .43 (.33, .52) |

.12 (.04, .19) |

.45 (.41, .50) |

|

| Non-Cognitive Composite | .67 | .34 | .27 | .10 | .62 (.53, .69) |

.05 (.00, .13) |

.33 (.30, .37) |

|

How Do Families Foster College Attainment in Their Offspring?

Our analyses thus far have shown that there is strong familial aggregation for educational attainment and that this aggregation is due to both genetic and shared environmental factors. We have also shown consistent associations between both cognitive and non-cognitive skills and college attainment. A natural question to ask is whether the shared environmental effect for college attainment arises because socially advantaged parents are more effective in fostering in their children the cognitive and non-cognitive skills needed for academic success than are parents who are less socially advantaged. As a first step towards answering this question, we report in Figure 4 a heat map rendition of the correlations among the cognitive, non-cognitive, and family background predictors separately in the SIBS adopted offspring sample (below the diagonal) and the combined MTFS and non-adopted SIBS samples (above the diagonal). Prior to estimating the correlations given in the figure, the effects of age at assessment and gender were regressed out separately in the two studies. Several patterns are evident in the figure. First, the non-cognitive and family background factors were similarly intercorrelated in the two groups, the figure is nearly symmetric for these variables. Second, the single cognitive measure, IQ, was generally weakly correlated with the non-cognitive measures, with the possible exception of Academic Problems. Finally, the correlations between the family background measures and the cognitive and non-cognitive measures differed in the two groups. That is, in the sample that included individuals who were reared by their genetic parents (above the diagonal) there were consistent albeit modest correlations. In contrast, in the sample that included individuals being reared by their adoptive parents, the correlations were uniformly small. For example, the largest correlation between a skill measure and a family background measure in the adopted sample was the correlation of .10 between IQ and the family background composite.

Figure 4.

Correlations among the cognitive, non-cognitive, and social background factors represented as a heat map. Correlations below the diagonal are for the adopted sample and above the diagonal are for the non-adopted sample. To facilitate comparison, correlations for negative qualities (designated with a *) have been reflected. Ordering of variables is the same as in Table 1, which can thus be used to translate the abbreviations.

To further explore the question of how parents might influence the college chances of their children, we report in Figure 5 the mean standardized IQ and Non-cognitive composite as a function of the number of parents completing college separately in the MTFS and non-adopted and adopted SIBS samples. The regression of IQ on number of parents with a college degree was statistically significant in both the MTFS (χ2 on 1 df= 155.9, p < .001) and non-adopted SIBS (χ2 on 1 df= 48.9, p <.001) samples. The regression coefficient (95% confidence interval) was comparable and large in the two samples: .42 (.36, .49) and .35 (.25, .45), respectively. Because IQ was standardized in these analyses, the regression coefficient gives the expected increase in IQ standard deviations for each additional parent with a college education. In contrast, although IQ was also significantly associated with number of college educated parents in the adopted SIBS sample (χ2 on 1 df= 6.6, p =.01), the magnitude of the association was markedly lower than in the other two samples (b=.13 (.03, .23)).

Figure 5.

Relationship of number of parents with a college degree with IQ and the Non-Cognitive Composite, both of which have been standardized. Error bars demarcate 95% confidence intervals.

The association between number of college educated parents and the Non-Cognitive composite also differed markedly across the samples. In the MTFS (χ2 on 1 df= 54.0, p < .001) and non-adopted SIBS samples (χ2 on 1 df= 24.6, p <.001), the association was statistically significant and moderate in magnitude, b = .20 (.15, .26) and .23 (.14, .33) respectively. In contrast, in the adopted SIBS sample, the regression was non-significant (χ2 on 1 df= .01, p =.96), with b = .00 (-.09, .09)

Discussion

Our analysis of college attainment in two large longitudinal samples spanning adolescence through early adulthood found that: 1) there is strong familial aggregation for college attainment, due to both genetic and shared environmental factors, 2) family background, cognitive skills and non-cognitive skills contribute independently to the prediction of college attainment, and 3) the family background effect on college attainment does not appear to be a consequence of environmentally-mediated effects on either cognitive or non-cognitive skills. Before discussing the significance of these findings it is helpful to acknowledge the limitations of our research design. First, our samples were ascertained through various Minnesota state records. Minnesota is not representative of the United States and it is certainly not representative of non-U.S. countries. Minnesota has higher rates of college graduation and lower rates of unemployment than most other U.S. states. It is also ethnically more homogeneous. This may limit the generalizability of our findings. Second, it is well known that there is restriction in the range of socioeconomic background in adoptive families, which could lead to an under-estimation of the importance of shared environmental influences (Stoolmiller, 1999). Nonetheless, we found consistent and strong evidence of a shared environmental influence on college attainment across our adoptive and twin samples and the intercorrelations of the individual-level and family background variables did not differ markedly across samples, suggesting that range restriction may not be a major limitation in this study. Third, our assessments of academic effort and problems were based on parent report. Finally, the offspring in SIBS were not all old enough at the time of their last follow-up to have had an opportunity to complete a four-year college degree. Consequently, in that sample the educational outcome measure was either completing a college degree or being currently enrolled in college. Despite the difference in outcome measure, findings from the MTFS and SIBS sample were very similar.

Our finding strong familial aggregation for college attainment is consistent with an extensive literature on familial resemblance for educational attainment (Hertz et al., 2007). Biometric analysis of the MTFS data indicated that both genetic and shared environmental factors contributed to the familial aggregation of college attainment, which is consistent with a recent meta-analysis of 21 different twin studies of educational attainment in which Branigan et al. (2013) reported meta-analyzed average estimates of 43% for additive genetic effects, 39% for shared environmental effects, and 18% for non-shared environmental effects. Although the college attainment phenotype was defined differently in the SIBS and MTFS samples, analysis of the former also provided evidence for shared environmental influences. Specifically, we found that adoptive parent college attainment was significantly associated with adopted offspring college attainment, and the adopted sibling correlation for college attainment of .37 is obviously consistent with the meta-analysis estimate of 39% for the shared environmental effect.

Our finding that genetic factors contribute to individual differences in college attainment is consistent with the long-standing recognition among social scientists that genetic factors contribute to, but do not totally account for, the intergenerational transmission of educational attainment (Bowles & Gintis, 2002). Alternatively, while our finding of a significant shared environmental influence on college attainment is consistent with earlier research, including previous adoption studies (Plug & Vijverberg, 2003), the finding of a strong shared environmental influence runs counter to the general finding in behavioral genetics that shared environmental factors have minimal influence on behavior (Plomin & Daniels, 1987). This raises the question as to what sets educational attainment apart from the many other behavioral and social phenotypes investigated by behavioral geneticists. One major explanation for the environmentally mediated intergenerational transmission of educational attainment is that highly-educated parents are more effective in fostering skill development in their children than are less well educated parents (Harding et al., 2015). This hypothesis is not, however, supported by the findings reported in this paper.

To determine whether highly-educated parents increase the likelihood their children graduate from college through skill development, we needed to first identify the skills relevant to academic achievement. One factor that is clearly associated with academic success is cognitive ability, for which there is an extensive literature and supportive meta-analyses (Sackett, Kuncel, Arneson, Cooper, & Waters, 2009). In addition to cognitive ability, there are a host of non-cognitive factors associated with post-secondary achievement (Richardson et al., 2012). Most prominent among these are self-control (Duckworth & Seligman, 2005), emotional control (Ivcevic & Brackett, 2014), and academic motivation and effort (Richardson et al., 2012). That is, individuals who are highly motivated, able to focus their attention, work hard and postpone immediate gratification for long-term gain do well in school. In both the MTFS and SIBS samples, we found that personality measures of emotional and behavioral self-control, academic effort and focus, and externalizing psychopathology were all moderately and significantly associated with college attainment. The strength of association for these non-cognitive factors was comparable to, and in the case of the academic specific measures of effort and problems, greater than the strength of the association for cognitive ability. Moreover, because the two domains of functioning are largely uncorrelated in our sample, non-cognitive and cognitive skills contributed independently to the prediction of college attainment.

Previous research has shown that family SES is positively associated with children's cognitive and, to a lesser degree, non-cognitive skills (Silles, 2011; Strenze, 2007). Consistent with this literature, we found significant correlations between indicators of family background and cognitive and non-cognitive skills in the MTFS and the non-adopted SIBS samples. The difficulty in interpreting these associations, however, is that they potentially confound genetic with shared environmental mechanisms of influence, which adoption studies can help to resolve. In the adopted SIBS sample, family background was uncorrelated with non-cognitive skills and only weakly but significantly correlated with cognitive skill. These findings suggest that highly educated parents may not be effective in fostering development of their children's non-cognitive skills and only modestly effective in developing their cognitive skills. Moreover, this pattern of findings is consistent with the observation that increases in compulsory education in Sweden in the parent generation was associated with a modest increase in offspring cognitive skills but not in offspring non-cognitive skills (Lundborg, Nilsson, & Rooth, 2014), as well as with the biometric analysis of the individual-level skill variables reported here in which we found little evidence for shared environmental influence other than a modest effect for IQ.

Social scientists have often emphasized the importance of fostering skill formation in accounting for the familial transmission of social inequality(Farkas, 2003). Yet our findings suggest that the association of family SES with offspring cognitive and non-cognitive skills is due largely to genetic factors. Nonetheless, we find consistent and strong evidence for a shared environmental effect on college attainment, so if not through skill development how do parents environmentally influence their children's educational opportunities? One possibility is through direct economic benefits (e.g., tuition payment), and although family income was the weakest SES predictor of college attainment in the MTFS and non-adopted SIBS samples it was the strongest SES predictor in the adopted SIBS sample. Alternatively, sociologists have argued that parents can create a culture that helps build their children's social capital (Portes, 1998). That is, high-SES parents may increase the chances their children succeed academically by setting high academic standards and expectations and by creating a social network where academic achievement is modeled and valued (Kim, 2014). We have not directly tested the social capital hypothesis here, although we note it finds support in other research. Increases in compulsory education in Germany, for example, have resulted in parents placing greater value on their children's academic success (Piopiunik, 2014). In any case, our finding of a strong shared environmental effect on college attainment supports the contention that in the U.S. inequities in educational opportunities that arise at the family level contribute to social inequities(Guo & Stearns, 2002; Nielsen & Roos, 2015).

Conclusion

Analysis of longitudinal twin-family and adoptive-family data led us to determine that both genetic and shared environmental factors contribute substantially to the intergenerational transmission of college attainment. College attainment is also consistently associated with cognitive ability and independently with a range of non-cognitive skills associated with self-control, academic motivation, and willingness to work hard. Nonetheless, the shared environmental mechanism by which highly-educated parents increase the likelihood their children are also highly educated does not appear to be mediated through skill development; other pathways need to be explored.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The research reported here and the preparation of this manuscript was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA09367, AA11886), National Institute of Mental Health (MH066140), and National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA05147, DA013240, DA036216)

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Our use of the term skill to refer to the cognitive and non-cognitive factors that underlie academic and social success may seem peculiar because it seems to imply these attributes are acquired through practice. Although we do not necessarily endorse the position that the factors we are exploring were acquired through practice, to be consistent with how the term has been used in the literature, we will use skill here in the general sense of a talent or aptitude.

Because the college attainment outcome was defined differently in the two samples, being completion of a four-year degree in MTFS and completion of a four-year degree or currently attending college in SIBS, we elected to not pool the two samples in analyses that looked at college attainment as an outcome.

References

- Björklund A, Lindahl M, Plug E. The origins of intergenerational associations: Lessons from Swedish adoption data. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2006;121(3):999–1028. doi: 10.1162/qjec.121.3.999. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Björklund A, Salvanes KG. Education and Family Background: Mechanisms and Policies. Handbook of the Economics of Education. 2011;3(3):201–247. doi: 10.1016/s0169-7218(11)03003-6. [Article; Book Chapter] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boardman JD. State-Level Moderation of Genetic Tendencies to Smoke. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(3):480–486. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2008.134932. [Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles S, Gintis H. The inheritance of inequality. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2002;16(3):3–30. doi: 10.1257/089533002760278686. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Branigan AR, McCallum KJ, Freese J. Variation in the Heritability of Educational Attainment: An International Meta-Analysis. Social Forces. 2013;92(1):109–140. doi: 10.1093/sf/sot076. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya S, Marchi KS, Metzler M, Posner S. Socioeconomic status in health research - One size does not fit all. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294(22):2879–2888. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879. [Review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Michael L, Nancy SB, Kessler RC. Mental disorders and subsequent educational attainment in a US national sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42(9):708–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.016. [Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Ceci SJ. Natre-nurture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychological Review. 1994;101(4):568–586. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.101.4.568. [Review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Furnham A. The Associations Between Parental Socio-Economic Conditions, Childhood Intelligence, Adult Personality Traits, Social Status and Mental Well-Being. Social Indicators Research. 2014;117(2):653–664. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0364-1. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Walque D. Does education affect smoking behaviors? Evidence using the Vietnam draft as an instrument for college education. Journal of Health Economics. 2007;26(5):877–895. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.12.005. [Article] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dee TS. Are there civic returns to education? Journal of Public Economics. 2004;88(9-10):1697–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.11.002. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth AL, Peterson C, Matthews MD, Kelly DR. Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92(6):1087–1101. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087. [Article] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth AL, Quinn PD. Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (Grit-S) Journal of Personality Assessment. 2009;91(2):166–174. doi: 10.1080/00223890802634290. [Article] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth AL, Seligman MEP. Self-discipline outdoes IQ in predicting academic performance of adolescents. Psychological Science. 2005;16(12):939–944. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01641.x. [Article] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eide ER, Showalter MH. Estimating the relation between health and education: What do we know and what do we need to know? Economics of Education Review. 2011;30(5):778–791. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.03.009. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esch P, Bocquet V, Pull C, Couffignal S, Lehnert T, Graas M, Ansseau M. The downward spiral of mental disorders and educational attainment: a systematic review on early school leaving. Bmc Psychiatry. 2014;14 doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0237-4. [Review] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas G. Cognitive skills and noncognitive traits and behaviors in stratification processes. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:541–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100023. [Review] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano PA, Reavis RD, Keane SP, Calkins SD. The role of emotion regulation in children's early academic success. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45(1):3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.09.002. [Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross C, Jobst A, Jungbauer-Gans M, Schwarze J. Educational returns over the life course. Zeitschrift Fur Erziehungswissenschaft. 2011;14:139–153. doi: 10.1007/s11618-011-0195-2. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Stearns E. The social influences on the realization of genetic potential for intellectual development. Social Forces. 2002;80(3):881–910. doi: 10.1353/sof.2002.0007. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harding JF, Morris PA, Hughes D. The relationship between maternal education and children's academic outcomes: A theoretical framework. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2015;77(1):60–76. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12156. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon C, Walker I. Estimates of the economic return to schooling for the United Kingdom. American Economic Review. 1995;85(5):1278–1286. [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, Risley TR. Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ, Kautz T. Hard evidence on soft skills. Labour Economics. 2012;19(4):451–464. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2012.05.014. [Article; Proceedings Paper] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ, Vytlacil E. Identifying the role of cognitive ability in explaining the level of and change in the return to schooling. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2001;83(1):1–12. doi: 10.1162/003465301750159993. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz T, Jayasundera T, Piraino P, Selcuk S, Smith N, Verashchagina A. The inheritance of educational inequality: International comparisons and fifty-year trends. B E Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy. 2007;7(2) [Article] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Two Factor Index of Social Position. New Haven, Connecticut: August B. Hollingshead; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance use disorders: Findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivcevic Z, Brackett M. Predicting school success: Comparing Conscientiousness, Grit, and Emotion Regulation Ability. Journal of Research in Personality. 2014;52:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2014.06.005. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlenberg RD. Left behind: Unequal opportunity in higher education. The Century Foundation; 2008. http://www.tcf.org: [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS. Assessing adolescents and adult intelligence. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kim KN. Formation of Educational Expectations of Lower Socioeconomic Status Children. Education and Urban Society. 2014;46(3):352–376. doi: 10.1177/0013124512446306. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl GO, Lengua LJ, McMahon RJ. Parent involvement in school conceptualizing multiple dimensions and their relations with family and demographic risk factors. Journal of School Psychology. 2000;38(6):501–523. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4405(00)00050-9. [Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Scholomskas D, Thompson WD, Belanger A, Weisman MM. Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: A methodlogical study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1982;39:879–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochner L, Moretti E. The effect of education on crime: Evidence from prison inmates, arrests, and self-reports. American Economic Review. 2004;94(1):155–189. doi: 10.1257/000282804322970751. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lundborg P, Nilsson A, Rooth DO. Parental Education and Offspring Outcomes: Evidence from the Swedish Compulsory School Reform. American Economic Journal-Applied Economics. 2014;6(1):253–278. doi: 10.1257/app.6.1.253. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Keyes M, Sharma A, Elkins I, Legrand L, Johnson W, Iacono WG. The environments of adopted and non-adopted youth: Evidence on range restriction from the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS) Behavior Genetics. 2007;37(3):449–462. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH. Mx: Statistical modeling. 6th. Box 126 MCV, Richmond VA 23298: Department of Psychiatry; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen F, Roos JM. Genetics of educational attainment and the persistence of privilege at the turn of the 21st century. Social Forces, Advanced access. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.02.006. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piopiunik M. Intergenerational transmission of education and mediating channels: Evidence from a compulsory schooling reform in Germany. Scandinavian Journal of Economics. 2014;116(3):878–907. doi: 10.1111/sjoe.12063. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, Daniels D. Why are children in the same family so different from one another? Behavior and Brain Sciences. 1987;10:1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Plug E, Vijverberg W. Schooling, family background, and adoption: Is it nature or is it nurture? Journal of Political Economy. 2003;111(3):611–641. doi: 10.1086/374185. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poropat AE. A meta-analysis of the Five-Factor Model of personality and academic performance. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(2):322–338. doi: 10.1037/a0014996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A. Social Capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology. 1998;24:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radford AW, Berkner L, Wheeless SC, Shepherd B. Persistence and Attainment of 2003–04 Beginning Postsecondary Students: After 6 Years (NCES 2011-151) Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reich W. Diagnostic interview for children and adolescents (DICA) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:14–15. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson M, Abraham C, Bond R. Psychological correlates of university students' academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2012;138(2):353–387. doi: 10.1037/a0026838. [Review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustichini A, Iacono WG, McGue M. The contribution of cognitive, non-cognitive skills and family background to educational mobility. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, submitted 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Sackett PR, Kuncel NR, Arneson JJ, Cooper SR, Waters SD. Does socioeconomic status explain the relationship between admissions tests and post-secondary academic performance? Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(1):1–22. doi: 10.1037/a0013978. [Review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan MJ, Bauldry S, Roberts BW, Macmillan R, Russo R. Personality and the Reproduction of Social Class. Social Forces. 2014;93(1):209–240. doi: 10.1093/sf/sou050. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silles MA. The intergenerational effects of parental schooling on the cognitive and non-cognitive development of children. Economics of Education Review. 2011;30(2):258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.09.002. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sirin SR. Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research. 2005;75(3):417–453. doi: 10.3102/00346543075003417. [Review] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoolmiller M. Implications of restricted range of family environments for estimates of heritability and nonshared environment in behavior-genetic adoption studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:392–409. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strenze T. Intelligence and socioeconomic success: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal research. Intelligence. 2007;35(5):401–426. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2006.09.004. [Review] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suizzo MA, Stapleton LM. Home-based parental involvement in young children's education: Examining the effects of maternal education across US ethnic groups. Educational Psychology. 2007;27(4):533–556. doi: 10.1080/01443410601159936. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, Waller NG. Exploring personality through test construction: Development of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. In: Boyle GJ, Matthews G, Saklofske DH, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment: Vol 2 Personality Measurement and Testing. London: Sage; 2008. pp. 261–292. [Google Scholar]

- Turkheimer E. Three laws of behavior genetics and what they mean. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2000;9(5):160–164. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00084. [Article] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uludag O. The influence of Aggression on Students' Achievement: Evidence from Higher Education. 2nd Cyprus International Conference on Educational Research (Cy-Icer 2013) 2013;89:954–958. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.963. [Proceedings Paper] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. 2015 Retrieved 03/01/2015, from http://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/education/data/cps/historical/

- Welner Z, Reich W, Herjanic B, Jung K, Amado H. Reliability, validity, and parent-child agreement studies of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA) Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1987;26:649–653. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198709000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]