Abstract

Purpose

We investigated the role of the human endogenous retrovirus type K (HERV-K) envelope (env) gene in pancreatic cancer (PC).

Experimental Design

shRNA was employed to knockdown (KD) the expression of HERV-K in PC cells.

Results

HERV-K env expression was detected in seven PC cell lines and in 80% of PC patient biopsies, but not in two normal pancreatic cell lines or uninvolved normal tissues. A new HERV-K splice variant was discovered in several PC cell lines. RT activity and virus-like particles were observed in culture media supernatant obtained from Panc-1 and Panc-2 cells. HERV-K viral RNA levels and anti-HERV-K antibody titers were significantly higher in PC patient sera (N=106) than in normal donor sera (N=40). Importantly, the in vitro and in vivo growth rates of three PC cell lines were significantly reduced after HERV-K KD by shRNA targeting HERV-K env, and there was reduced metastasis to lung after treatment. RNA-seq results revealed changes in gene expression after HERV-K env KD, including RAS and TP53. Furthermore, downregulation of HERV-K Env protein expression by shRNA also resulted in decreased expression of RAS, p-ERK, p-RSK, and p-AKT in several PC cells or tumors.

Conclusion

These results demonstrate that HERV-K influences signal transduction via the RAS-ERK-RSK pathway in PC. Our data highlight the potentially important role of HERV-K in tumorigenesis and progression of PC, and indicate that HERV-K viral proteins may be attractive biomarkers and/or tumor-associated antigens, as well as potentially useful targets for detection, diagnosis and immunotherapy of PC.

Keywords: HERV-K, pancreatic cancer, shRNA, RAS-ERK-RSK pathway

Introduction

Human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) and related gene sequences make up about 8% of the human genome, and some HERVs may retain retroviral functions, including tumor induction. Abundant studies have reported the relationship between HERV-K and human diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis (1), and the hotspot of these studies is the association between HERV-K and cancers (2–10). HERV-K is thought to be transcriptionally silent in normal cells, and becomes active after malignant transformation (8,11), except in the case of brain tumors (12). Increased expression of HERV-K has been detected in human cancers (8,13–21), and transcripts of HERVs have been detected by many independent investigators in various types of cancer that include breast cancer (8,22,23), ovarian cancer (24, 25), lymphoma (26,27), melanoma (11,28–32), germ line tumors (33–35), and prostate cancer (5, 36). Our laboratory showed that the HERV-K family is active and overexpressed in breast cancer (2,23,37–40): HERV-K expression was detected in 45% to 93% of primary breast tumors (N=479), and a higher rate of lymph node metastasis was associated with HERV-K-positive compared with HERV-K-negative tumors.(23,37,39–41). Although HERV-K is the most complete and biologically active family of HERVs, the precise mechanism leading to abnormal HERV gene expression has yet to be clearly understood. Our results below and recent publications [ours (42) (39,41) and others (43)] provide strong evidence that abnormal expression of HERV-K triggers pathological processes leading to cancer onset, and also contributes to the morphological and functional cellular modifications implicated in cancer progression (2–9). HERV-K can express two accessory viral proteins, Rec and NP9, which are believed to have oncogenic potential (44). In addition, HERV-K virus-like particles have been detected in teratocarcinoma (45), breast cancer (22), melanoma (46), and lymphoma (22).

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer death for both men and women in the U.S. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) accounts for >90% of the total pancreatic cancer burden. PDAC is a rapidly lethal disease and most patients die within a year after diagnosis (47). The disease usually is diagnosed at later stage and the tumor is highly aggressive. PDAC is highly resistant to current chemo-radiation therapies (48). Unfortunately, many of the emerging immune-oncology approaches that have shown dramatic effects in certain solid cancers, such as antibodies against immune checkpoint proteins, have been ineffective in PDAC (49,50). Novel strategies in early detection and effective treatment of PDAC are in urgent need.

There has been no direct evidence linking HERV-K and human PC. However, when seeking to identify novel cancer antigens in PC for immunotherapy applications, it was found that the peptide HERV-K-MEL is expressed in 23% of malignant, but not in non-malignant, pancreatic tissues (51). Hohn et al. reviewed studies showing that HERV-K-MEL is a pseudo-gene incorporated into the HERV-K env gene (52) and is thus not a HERV-K peptide. In addition, HERV-K-MEL is inserted in HERV-K(HML-6), whose sequence is different from the more commonly investigated HERV-K(HML-2) sequence we are evaluating in this study. Importantly, we found that the percentages of HERV-K–positive PCs were much higher than the 23% level of expression reported for HERV-K-MEL in PC tissues (see Results). Therefore, we investigated the expression of HERV-K in PC cells and tissues, and evaluated its potential for early detection and therapy of PC. Furthermore, we evaluated suppression of PC cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo by short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting HERV-K env RNA.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines, tissues, and sera

The human PC cell lines Panc-1, Panc-2, Colo-357, SU8686, AsPC-1, MIA PaCa-2 and BxPC-3 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA). The nonmalignant pancreatic cell line HPDE-E6E7 was a gift from Dr. Min Li (53) and the nonmalignant hTERT-HPNE human pancreatic duct cell line was obtained from ATCC. Cells were maintained in the culture media recommended by the provider for about 3 passages before the experiments were carried out. Cell line authentication and mycoplasma testing was not performed. PC tissues with matched adjacent uninvolved pancreatic tissues from the same patients were obtained from US Biomax Inc. Serum samples were obtained from cancer patients and normal donors at the MD Anderson Cancer Center according to an approved Institutional Review Board protocol (LAB05-0785) and written informed consent was provided by study participants and/or their legal guardians. PC patients with pathologically confirmed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma were consecutively recruited at the Gastrointestinal Cancer Clinic of MD Anderson Cancer center during June 2006 to November 2007. A blood sample was collected with patients’ written consent and 84% of the samples were collected within 2 months of the cancer diagnosis. Serum samples were stored at −80°C before testing. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are described in Supplementary Table 1 (sTable 1).

3D Culture

For 3D cell culture, Matrigel HC (BD Biosciences) was thawed on ice and diluted with precooled complete culture medium (1:1 v/v). Ten dots (15 μl of diluted Matrigel per dot) were pipetted onto a dry 60×15 mm Petri dish. A cell suspension of 1 μl (50 cells/μl) was pipetted onto each dot. Dots were allowed to gel for 5 minutes in a 37°C incubator. A second dot was pipetted on top of the first one. A cell suspension of 1 μl (50 cells/μl) was again pipetted onto each dot. After the dots began to wrinkle, cell culture medium was added to cover the dots. 3D cultured cells were allowed to grow for 2 or more days.

RT-PCR and DNA sequence analysis

RNA was isolated from cells or tumor biopsy specimens using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, OH), and multiple HERV-K gene fragments were amplified by RT-PCR as described previously (37,38).

Viral RNAs (vRNAs) (60 μl) were isolated from 140 μl of serum or cell culture media using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCT was carried out using the TaqMan® One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix Reagents Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA) or by RT-PCR, as described previously (38). The vRNA abundance was calculated in a ‘copy-per-ml’ format, based on a standard curve generated from serial dilution of cRNA of HERV-K genes (54,55). All the primers and probes used in RT-PCR or qRT-PCR are listed in sTable 2.

HERV recombinant fusion proteins and antibodies

The recombinant fusion protein K-GST, which consists of surface domain (SU) of HERV-K Env protein cloned into an expression vector encoding glutathione transferase (GST), was induced by IPTG and affinity purified using an ÄKTA FPLC (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) equipped with a GSTrap column (GE Healthcare) as described previously (24). NP9 recombinant fusion proteins (also fused with GST) were induced and affinity purified as for K-GST. Anti-HERV-K monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) 6H5 and 6E11 were produced and purified as described previously (24). Several assays were used to determine the specificity and sensitivity of anti-HERV-K monoclonal antibodies as described previously (39). The purified mAbs were used for ELISA, Western blotting, and other immunoassays, as described below.

Immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence staining, ELISA/cell ELISA, immunoblot and flow cytometry

Immunofluorescence staining, ELISA/cell ELISA, immunoblot and immunohistochemistry were performed to determine the expression of HERV-K Env protein in cells or tissues, as described previously (23,56) (24). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on 5 μm formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections using standard protocols and a Vectastain ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), as described previously (23). Antibodies including p-RSK (RPS6KA1/2/4) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), p-ERK1/2 (MAPK3/1), p-Rb (Rb1), p-AKT (AKT1) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); RAS (total RAS) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) were used for immunoblot at a 1:1000 dilution. Dilution of ACTB (University of Iowa) was 1:200.

mAb conjugation to gold nanoparticles

Dialyzed 6H5 (500 μg) was incubated with 50 ml of 5-nm or 30-nm colloidal gold, pH 7.4, with gentle agitation, and purified by size-exclusion chromatography using ÄKTA FPLC.

Viral fragment isolation, reverse transcriptase activity, and transmission electron microscopy

Virus-like particles were purified from cell culture media with a 50% iodixanol (OptiPrep Density Gradient Medium; Sigma-Aldrich) cushion as recommended by the manufacturer. The sample was then centrifuged as described previously (22). Fractions of about 100 μl each were serially collected and the reverse transcriptase (RT) activity in 5 μl of each fraction was measured using the EnzChek RT assay kit (Invitrogen), as described by the manufacturer. An RT standard curve was included using serial dilutions of MMLV RT (1:3,000, 1 to 9,000, and 1:27,000: Invitrogen). Virus-like particles from RT-positive iodixanol fractions with a density characteristic of retroviruses were absorbed to 300-mesh carbon-coated nickel grids and the samples were stained with 2% uranyl acetate and imaged with a Tecnai Spirit transmission electron microscope (TEM) (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) operating at 80 kV. For labeling with gold nanoparticles (GNPs), 500 μl of high RT enzyme activity–containing fractions of Panc-2 cell culture media supernatant was incubated with 10 μg of 6H5 conjugated with 30-nm GNPs overnight at 4°C with gentle agitation. The next day, samples were prepared as whole mounts on 300-mesh nickel grids and negatively stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate for 5 minutes. Grids were imaged by TEM as described above.

HERV-K Env shRNA lentiviral packaging

shRNAs targeting the HERV-K env gene (shRNAenv, the sequence is: CCTGAACATCCAGAATTAT) (GenBank No. M14123.1) (HML-2) and matched scrambled shRNA sequences serving as negative controls (shRNAc, the sequence is: GAATTCTTAACGACTACCA) were designed using the RNAi Designer program (Invitrogen) and cloned into the pGreenPuro™ vector (System Biosciences). The shRNA-expressing lentiviral particles were then packaged and titered according to the manufacture’s protocol.

Lentiviral vector transduction

Panc-1, Panc-2 or BxPC-3 cells (1×105) were seeded into individual wells of 6-well plates and infected with lentiviral particles carrying shRNAenv or matched shRNAc at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 40. RT-PCR, qRT-PCR and /or immunoblot were performed to detect HERV-K Env expression after two weeks.

Cell proliferation and anchorage-independent growth

1 × 105 cells per well were plated in complete medium in a 24-well plate and incubated for 72 h. Cells were then harvested, and cell proliferation rates were measured by counting viable cells using the trypan blue dye exclusion method. Anchorage-independent growth of shRNA-transduced cells was tested according to a published method (57).

Phosphorylation profiles of kinases in HERV-K knockdown cells

A Human Phospho-Kinase Array (ARY003B; R&D systems) was employed to simultaneously detect the relative site-specific phosphorylation of 43 kinases. Cellular extracts prepared from the Panc-1 or BxPC-3 cell line transduced with shRNAenv vs. shRNAc were compared and results obtained after 30 min exposure.

In vivo studies

Female immunodeficient nude, NOD/SCID (NCI, Frederick, MD) or NOD/SCID/gamma (NSG) (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) mice, 6- to 8-weeks of age (NCI, Frederick, MD), were inoculated subcutaneously in the flank with 1 × 106 Panc-1, Panc-2 or BxPC-3 cells transduced with shRNAenv or shRNAc to assess the phenotypes and potential for tumorigenesis of these cells in vivo. Tumors were harvested and weighed, and H&E staining was used to provide histologic evidence of malignancy. RNAs and proteins were isolated from both groups and the expression of HERV-K env RNA and HERV-K protein was determined by qRT-PCR/RT-PCR and immunoblot, respectively. Lung tissues were also collected and cultured, and metastatic Panc-1 or Panc-2 cells in the lung were compared between the two groups. All studies using mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of MD Anderson Cancer Center and SRI International.

RNA-Seq analysis

The libraries were sequenced using a 2×76 bases paired end protocol on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 instrument. Each library was sequenced in 1/6 lane, generating about 20–35 million pairs of reads per sample. The reads were mapped to human genome (hg19) by TopHat (V2.0.6). The number of fragments in each known gene from the RefSeq database (downloaded from UCSC Genome Browser on March 09, 2012) was enumerated using htseq-count from HTSeq package (V0.5.3p9). The differential expression was statistically accessed by R/Bioconductor package edgeR (V3.0.8). Genes with FDR≤0.05 were called significant.

Statistical analysis

We used unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test to analyze differences between groups (GrapPad Prism 6). All statistical tests were two-sided, and differences between variables with a P value of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of multiple HERV-K env transcripts in pancreatic cancer cell lines

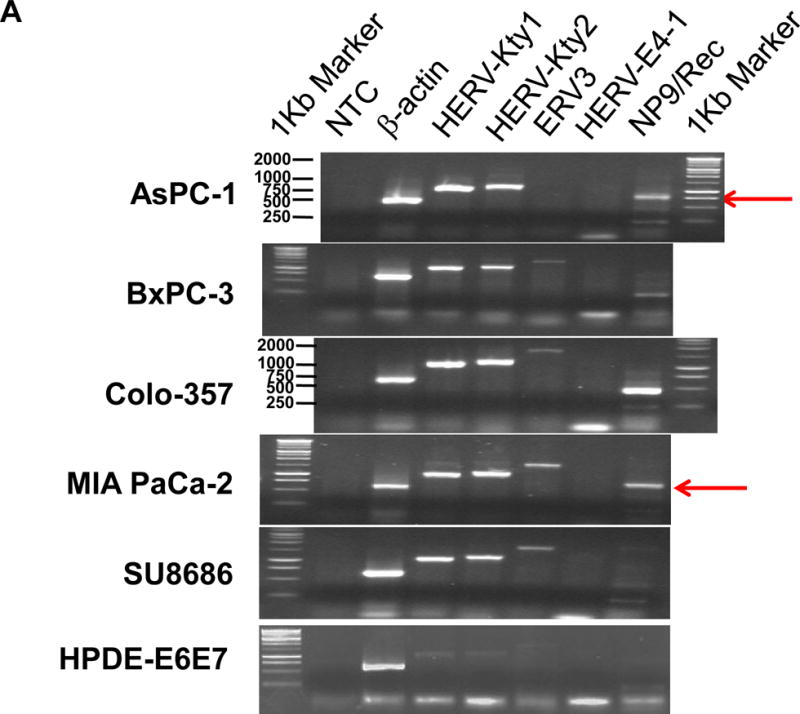

The expression of type 1 (1,104 bp) and type 2 (1,194 bp) transcripts of HERV-K env surface domain (SU) was detected in the PC cell lines AsPC-1, BxPC-3, Colo-357, MIA PaCa-2, SU8686, Panc-1 and Panc-2 to a greater extent than in the nonmalignant pancreatic ductal epithelium cell lines HPDE-E6E7 and hTERT-HPNE (Fig. 1A) using primers listed in Supplementary Table 1 (sTable 2). Fig. 1A also shows that HERV-K is overexpressed to a greater extent than some other HERVs, such as HERV-E4-1, in pancreatic cancer cells. Sequence analysis indicated that type 2 HERV-K env genes from PC cells share 99% identity with HERV-K102 (type 1) and HERV-K113/K115 (type 2), respectively. Importantly, the HERV-K env genes obtained from Panc-1, Panc-2, and Colo-357 lines have ORFs without any stop codon (sFig. 1A&1B), and proteins translated from these ORFs (sFig. 1B) are 93–99% identical to HERV-K115 Env protein sequences. In addition to HERV-K115, other subtypes that closely matched the consensus sequence included HERV-K (C19) envelope protein (Sequence ID: O71037.2; 98% identity), HERV-K113 (Sequence ID: YP_008603282.1; 96% identity), HERV-K_11q22.1 (Sequence ID: P61570.1; 96% identity), and HERV-K108 (Sequence ID: Q69384.1; 95% identity). These results revealed that HERV-K Env proteins, including both type 1 and type 2, are actively transcribed and potentially translated in PC cell lines (Panc-1, Panc-2, and Colo-357). Three stop codons were detected in HPDE-E6E7 cells (sFig. 1A and sFig. 1B).

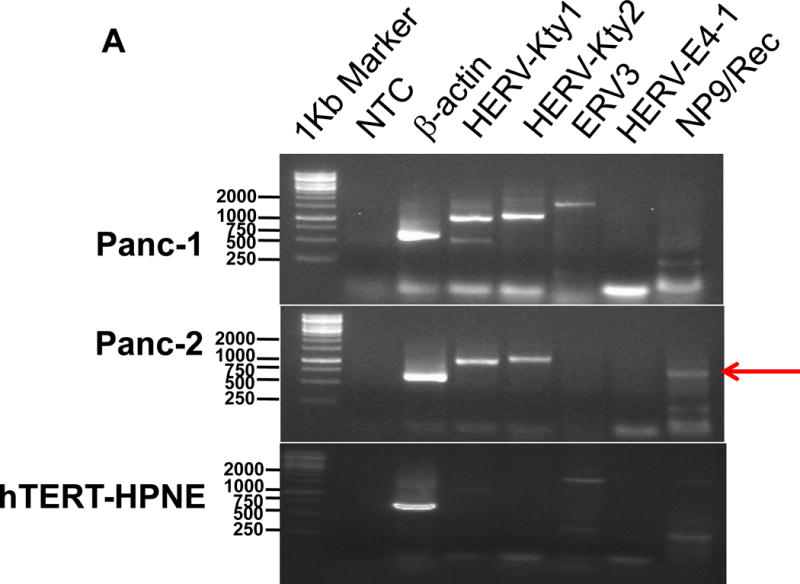

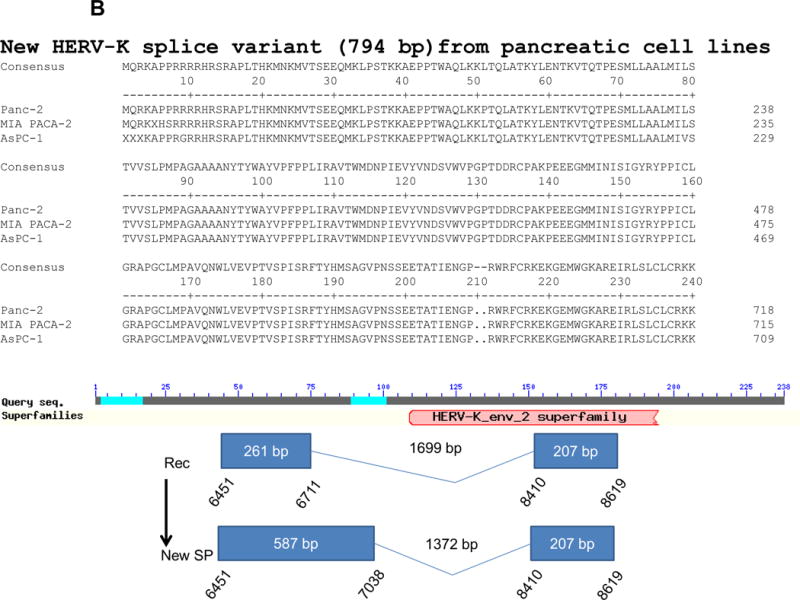

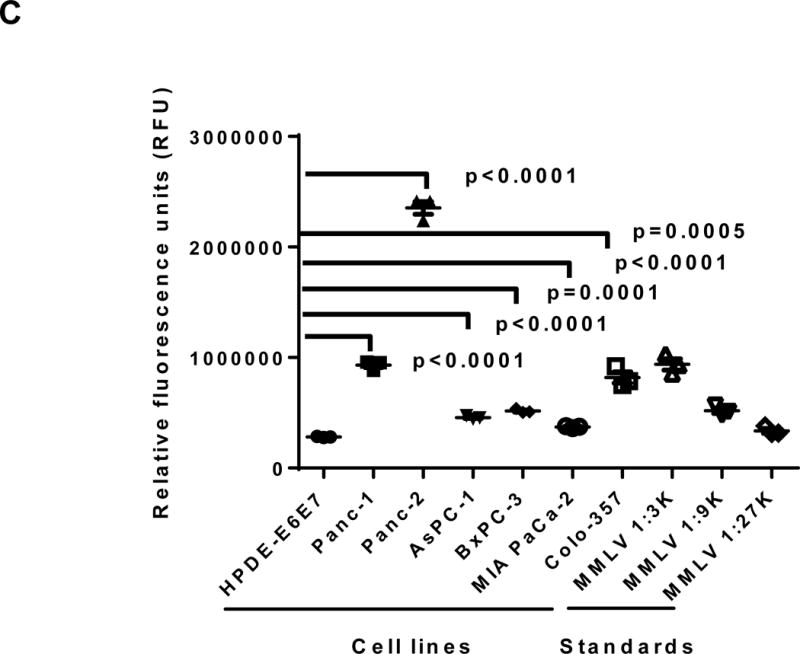

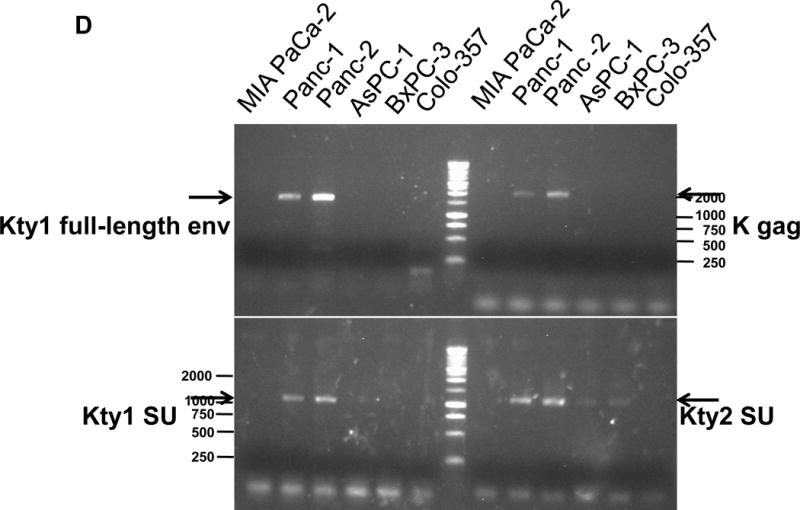

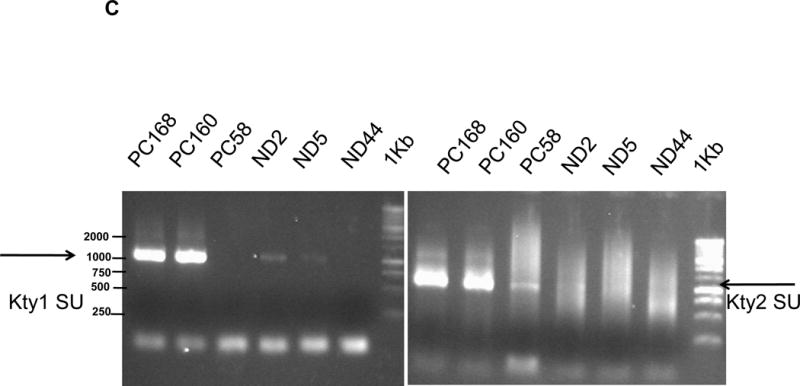

Figure 1.

Expression of human endogenous retroviruses and viral reverse transcriptase activity in pancreatic cancer cells and tissues. A, the expression of various HERV env mRNAs was evaluated in pancreatic cell lines by RT-PCR using corresponding primer pairs. NTC: no template control; β-actin: positive control. HERV-Kty1: type 1 HERV-K env SU (1,104 bp); HERV-Kty2: type 2 HERV-K env SU (1,194 bp); ERV3: ERV3 env, HERV-E4-1: HERV-E env; NP9/Rec: transcripts amplified using NP9 primers. A new HERV-K splice variant (794 bp) present in several PC cell lines is shown (red arrow). β-actin was used as housekeeping gene. B, the predicted amino acid composition of the HERV-K splice variant from several PC cell lines is shown. Furthermore, the splice donor and acceptor of the new HERV-K splice variant was compared with splice donors and acceptors of Rec (HERV-K113; AY037928.1). C, reverse transcriptase (RT) activity was compared in gradient fractions prepared with a 50% iodixanol cushion from cell culture media (200 ml) of various pancreatic cell lines. Relative florescence units (RFU) in various pancreatic cell lines were compared. Serial dilutions (1:3,000, 1:9,000, and 1:27,000) of MMLV RT (Stratagene) were used as calibrators (standards). Student’s t-test was used to find statistically significant differences in RT activity between each PC cell line compared with HPDE-E6E7 cell line. D, vRNAs were isolated from gradient fractions of PC cell culture media, and expression of HERV-K genes [HERV-K full-length env and gag, HERV-K type 1 SU RNA (Kty1SU), and HERV-K type 2 SU RNA (Kty2 SU)] was determined by RT-PCR using specific primers. The higher expression of vRNAs in Panc-1 and Panc-2 cells matched the RT activities in their culture media.

Expression of transcripts of the two HERV-K accessory viral proteins Rec (437 bp) or NP9 (256 bp) was observed in several PC cell lines using NP9-specific primer pairs (sTable 2). We also discovered a novel 794 bp env splice variant transcript of HERV-K in AsPC-1, MIA PaCa-2, and Panc-2 cells (Fig. 1A; red arrows). The new splice product (SP; 794 bp) seems unique to PC, since we have not observed its presence in other cancers we have evaluated for HERV-K expression (sFig. 1C). The novel splice donor (7,038) and acceptor site (8,410, K113 gb|AY037928.1|) was detected in these PC cell lines, and splice donor and acceptor sites from Rec and the new SP were compared (Fig. 1B; Bottom panel, sFig. 1D). Frame 1 in the new SP is longer than in Rec and they have the same size of frame 2.

Expression of ERV3 env transcript in pancreatic cancer cell lines

The expression of multiple HERV types was previously demonstrated in ovarian cancer by our group (24), and we evaluated expression of HERVs in addition to HERV-K in PC. The expression of transcripts of ERV3 env (1,700 bp) was detected in BxPC-3, Colo-357, MIA PaCa-2, SU8686, and Panc-1 cells, and at low levels in hTERT-HPNE cells. The HERV-E (1,348 bp) env region was not expressed in any of the cell lines (Fig. 1A).

The translated protein sequences of ERV3 Env protein are shown in sFig. 1E. One ERV3 env mRNA stop codon was identified in HPDE-E6E7, while ORFs without any stop codons were demonstrated in BxPC-3, Colo-357, MIA PaCa-2, Panc-1, and SU8686 cells, which share 99–100% identity with ERV3 Env protein sequences (GenBank AC# BAJ21154.1). Sequences of regions containing stop codons from various cell lines were compared, and a stop codon was found only in HPDE-E6E7 cells (sFig. 1F).

Reverse transcriptase activity and expression of viral RNA in cell lines

The activity of RT, an enzyme associated with retroviruses, was measured in culture media obtained from various PC cell lines. Higher RT activity was observed in PC cells than in HPDE-E6E7 pancreatic cells (Fig. 1C). Serial dilutions of Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) RT were used as standards. Media from cultured Panc-2 cells had the highest RT activity. There was significantly higher RT activity in all six PC cell samples compared with HPDE-E6E7 cells. The presence of HERV-K vRNA in fractions obtained from PC cell culture media (Panc-1 and Panc-2, Fig. 1D) was confirmed by RT-PCR analysis. The band intensity of RT-PCR products matched the RT activity from the same cell lines.

The presence of HERV-K–containing virus-like particles in Panc-2 culture media was demonstrated by TEM using 6H5 conjugated to GNPs (sFig. 2A; 6H5-GNP). vRNA presence was confirmed by sequence analysis of genes amplified from cell culture media obtained from PC cells. The protein sequences corresponding to RT-PCR–amplified HERV-K (type 1) full length env cDNA in Panc-2 culture media are shown in sFig. 2B. Two clones obtained from Panc-2 cell culture media had no stop codon and contained both the HERV-K env SU superfamily domain and transmembrane (TM) domain. The sequence with a stop codon at position 8,140 showed full-length translation of SU and TM domains (GP41).

The protein sequences corresponding to RT-PCR–amplified HERV-K type 1 env SU cDNA in the culture media of Panc-2 or Panc-1 cells are shown in sFig. 2C (Kty1 SU). In addition, HERV-K type 2 env SU cDNA (Kty2 SU) was detected in the culture media of several pancreatic cancer cell lines (AsPC-1, BxPC-3, Panc-1, and Panc-2) and their protein sequences are shown in sFig. 2D; HERV-K gag (Gag-p24) was detected in the culture media of Panc-2 and Panc-1 cells, and their protein sequences were shown in sFig. 2E. The presence of HERV-K–containing virus-like particles and complete viral gene sequences suggests that there might be active HERV-K viruses in some PC cells.

Expression of HERV-K Env protein in pancreatic cancer cell lines

The expression of HERV-K Env protein was detected in the PC cell lines AsPC-1, BxPC-3, Colo-357, MIA PaCa-2, Panc-1, Panc-2, and SU8686, but was nearly absent in the nonmalignant pancreatic cell line HPDE-E6E7 (Fig. 2A, left panel), as detected by immunofluorescence staining using mAb 6H5 that targets HERV-K Env SU (left panel). Comparable immunofluorescence staining with isotype mouse IgG2a is absent (sFig. 3A), demonstrating the specificity of anti-HERV-K mAb staining.

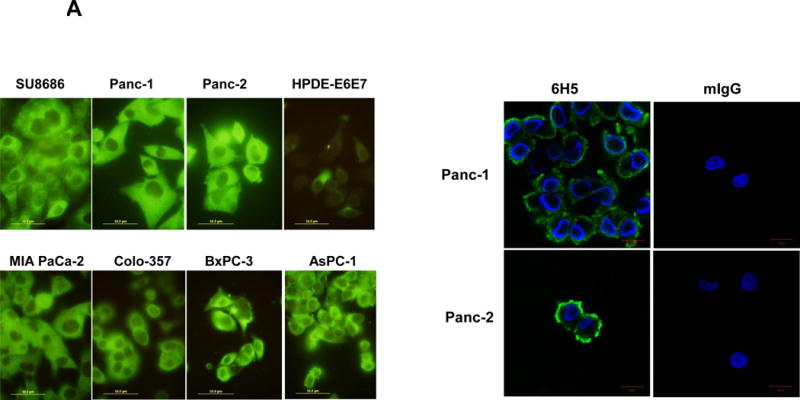

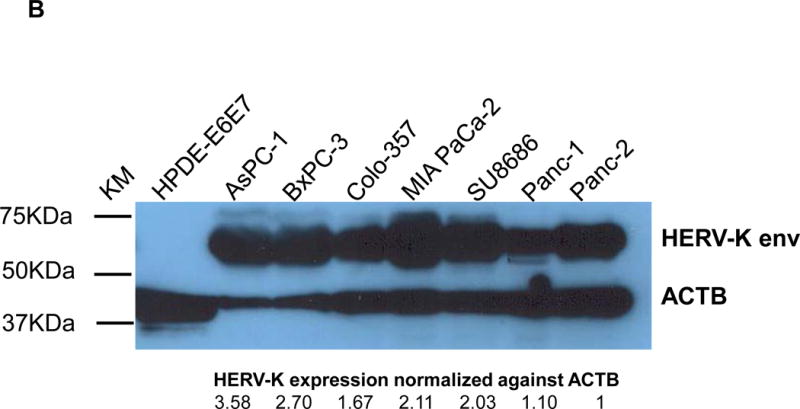

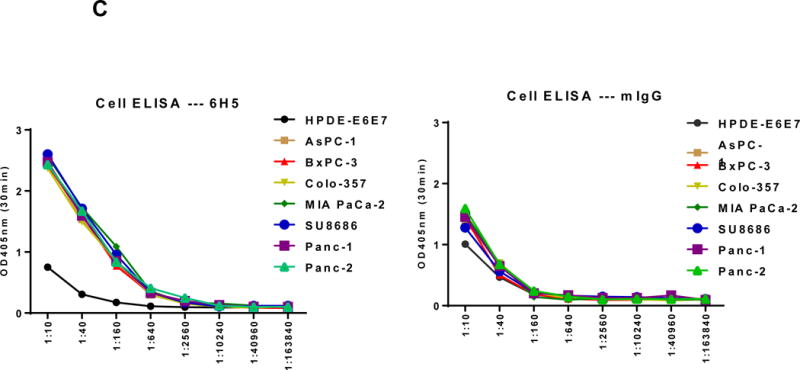

Figure 2.

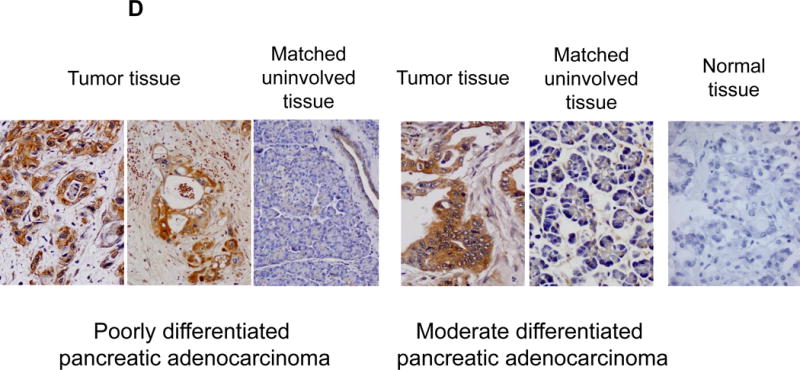

Detection of HERV-K Env protein expression in pancreatic cancer cells. A, expression of HERV-K Env protein was detected by immunofluorescence staining in seven PC cell lines as well as HPDE-E6E7 cells using 6H5 mAb (left panel). The expression of HERV-K Env SU protein on the cell membrane of Panc-1 or Panc-2 cells was demonstrated by confocal microscopy after immunofluorescence staining with 6H5 mAb; the control mIgG showed no staining (right panel). DAPI (blue color) was used for nuclear counterstain. B, expression of HERV-K Env protein was detected by immunoblot in seven PC cell lines but not in HPDE-E6E7 cells, using 6H5 mAb. ACTB was used as the control. The expression of HERV-K Env protein from high to low is AsPC-1 (3.58 fold), BxPC-3 (2.70 fold), MAI-PaCa-2 (2.11 fold), SU8686 (2.02 fold), Colo-357 (1.67 fold), Panc-1 (1.10 fold), and Panc-2 (1 fold). No expression of HERV-K was detected in HPDE-E6 E7 cells using Image J. C, expression of HERV-K Env protein on the various pancreatic cell lines was determined by cell ELISA using 6H5 mAb (left panel); mIgG was used as the control (right panel). The expression of HERV-K Env protein was detected to a greater extent in all seven PC cell lines tested than in HPDE-E6E7. D, strong expression of HERV-K was detected by immunohistochemistry in most PC tissues containing poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. HERV-K was not expressed in normal or matched uninvolved, non-neoplastic pancreatic tissues. The expression of HERV- K was compared in a patient with moderate differentiated adenocarcinoma including tumor biopsy and matched non-neoplastic pancreatic tissues.

The expression of HERV-K Env protein on the cell surface was demonstrated in Panc-1 and Panc-2 cells by confocal microscopy using mAb 6H5; no staining was observed using the mouse IgG (mIgG) control (Fig. 2A, Right panel). Z-stack images confirmed the cell membrane expression of HERV-K Env protein on a Panc-1 cell (sFig. 3B). The expression of HERV-K Env protein was further demonstrated in multiple PC cell lines, but not in HPDE-E6E7 cells by immunoblot (Fig. 2B) or by cell ELISA using serial dilutions of mAb 6H5, with mIgG as a control (Fig. 2C). HERV-K Env protein molecules were quantitated in various pancreatic cell lines by QIFI flow cytometry assays. The morphology of cells in 3D culture was compared with 2D cultures (sFig. 3C); PC cells grown in 3D culture formed spheres and proliferated more rapidly than HPDE E6E7 cells. Expression of HERV-K was enhanced in nearly every PC cell line in 3D cultures (sFig. 3D), and significantly higher expression of surface Env protein in BxPC-3 than in HPDE-E6E7 cells was demonstrated by cell ELISA (sFig. 3E).

Expression of HERV-K Env protein in human pancreatic tumor tissues

We examined HERV-K Env expression in 30 human stage II-IV PC biopsy specimens on a tissue array by IHC using mAb 6H5 as a detection antibody, as described previously (39). Selected examples of staining are shown in Fig. 2D. PC specimens, especially those from poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas, were positive for HERV-K staining, while specimens from normal pancreatic tissues (normal) or corresponding adjacent uninvolved non-neoplastic tissues were negative for HERV-K staining. The percentages of HERV-K–positive PCs were 63.6% for stage IIA (N = 7/11), 92.1% for stage IIB (N = 16/17), and 100% for stage III (N = 2) (overall positive percentage is 80%; N = 30).

Serum levels of anti-HERV-K antibodies or HERV-K viral RNA in pancreatic cancer patients

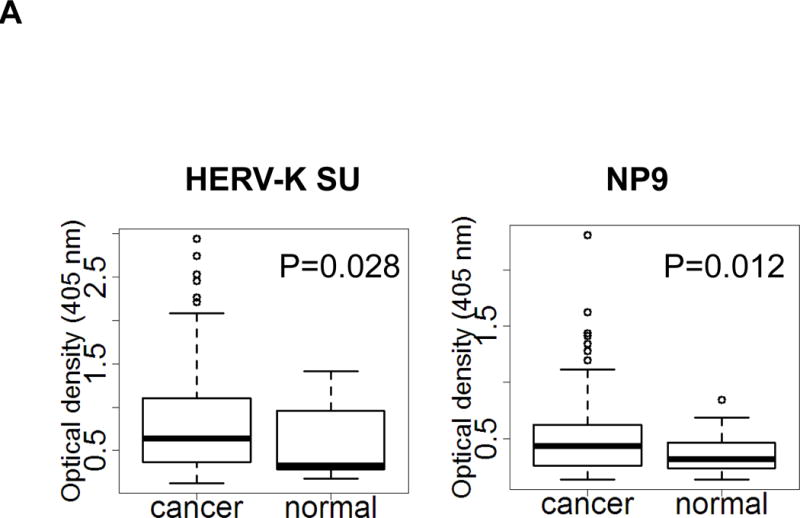

We next tested for the presence of anti-HERV-K antibodies or HERV-K vRNA in serum samples from PC patients (N =106) and normal donors (N = 20). The clinical characteristics of the 106 PC patients are described in sTable 1. Briefly, 54% of patients are older than 60, 66% are men and 90% are non-Hispanic Whites. At the time of recruitment, 33%, 31% and 34% patients had localized, locally advanced and metastatic disease, respectively. Tumor resection was achieved in 34% of patients. A significantly higher titer of antibody against HERV-K Env SU protein or NP9 protein was observed in sera from PC patients than in sera from normal donors (P = 0.028 or P = 0.012; Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

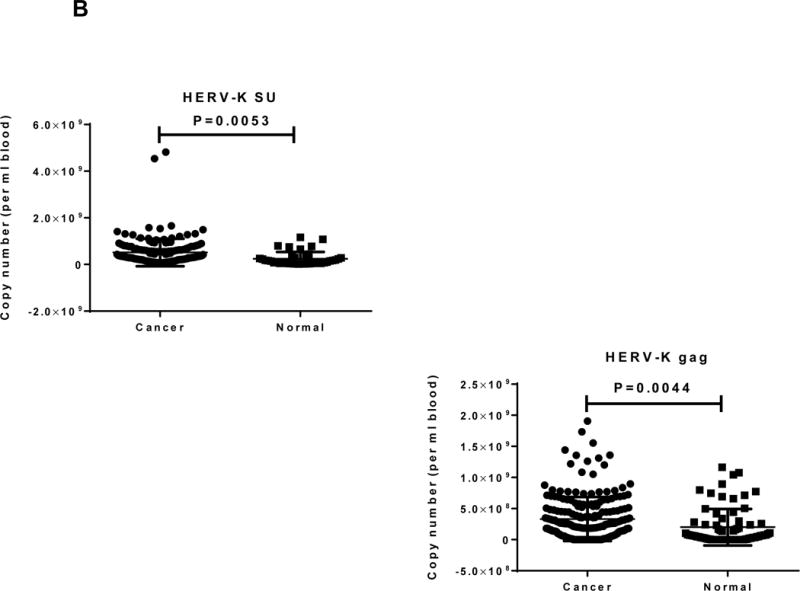

Determination of anti-HERV-K antibodies and vRNA levels of HERV-K in sera. A, anti-HERV-K (SU) (left panel) and anti-NP9 (right panel) serum antibody ELISA titers were compared between PC patients (N = 106) and normal donors (N = 20). A significantly higher titer of anti-HERV-K antibodies against SU (P = 0.028) and NP9 (P = 0.012) was observed in PC patients than in controls using the Mann-Whitney test. B, expression of HERV-K env (HERV-K env SU; left panel) or gag (HERV-K gag; right panel) vRNA was significantly higher in the sera obtained from PC patients than from normal donors (P = 0.0053 for env and P = 0.0044 for gag) by qRT-PCR. C, the levels of HERV-K vRNAs were further confirmed by RT-PCR using primers specific for both types (Kty1 and Kty2) of HERV-K env SU. The samples shown here include those with the highest (PC168 and PC160 from PC patients and ND2 and ND5 from normal donors) and lowest (PC58 from a PC patient and ND44 from a normal donor) copy number of env determined by qRT-PCR. The bands with the strongest intensity were detected for PC168 and PC160, and very weak bands were detected for ND2 and ND5 (type 1) or PC58 (type 2). No band was detected for ND44. For statistical analysis, an unpaired two-tailed t-test was used.

Age and gender for the subjects are included in sTable 1. We have tested the correlation of age and sex with marker levels using Pearson’s correlation test and Analysis of Variance. No significant association was found between age/sex and any markers.

Viral RNAs isolated from sera of PC patients were subjected to qRT-PCR using HERV-K env- and gag-specific primers and probes (sTable 2). The levels of vRNAs (copy number per ml blood), determined using HERV-K env SU (P = 0.0053) or gag (P = 0.0044) probes and primers, was significantly higher in sera from PC patients than in sera from normal donors (Fig. 3B). In addition, a significant association of vRNA levels with disease stage was observed. The percentage of patients with a higher level of viral env RNA (higher copy number than the mean copy number of controls) was 40%, 41.4%, and 75%, and viral gag RNA was 41.7%, 63.6%, and 84.4%, for patients with localized, locally advanced, and metastatic disease, respectively (P = 0.004 and P = 0.001, respectively). However, the HERK-V SU antibody titers were not associated with patient survival or vRNA level (sFigs. 4A and 4B) and no significant association was found between age/sex and any markers.

RT-PCR was employed to complement our qRT-PCR results. Representative results of RT-PCR are shown in Fig. 3C. The figure depicts results for 3 serum samples from the PC patients or from the normal donors, with the two highest and the one lowest qRT-PCR values Strong expression of type 1 and type 2 HERV-K env SU RNAs was detected in PC160 (Stage IV) and PC168 (Stage III), in comparison to very weak expression in ND2 and ND5. Meanwhile, weak or no HERV-K env SU bands were amplified from PC58 and ND44. Our RT-PCR data thus matched our qRT-PCR results. Sequencing results confirmed the expression of HERV-K type 1 (sFig 4C; top panel) and type 2 SU translated proteins (sFig.4C; bottom panel) in samples PC160 and PC168.

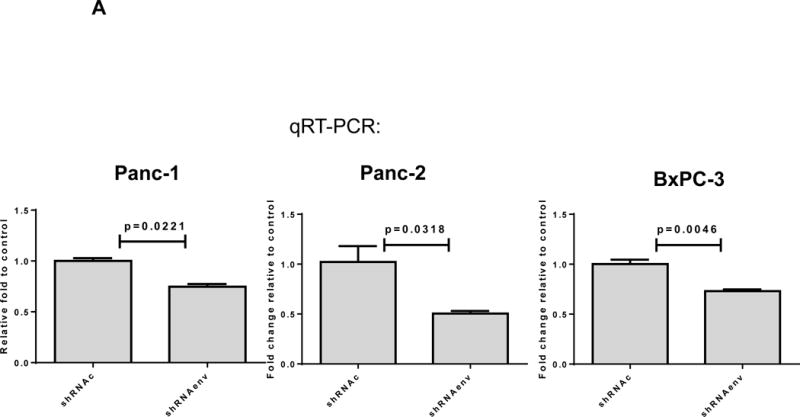

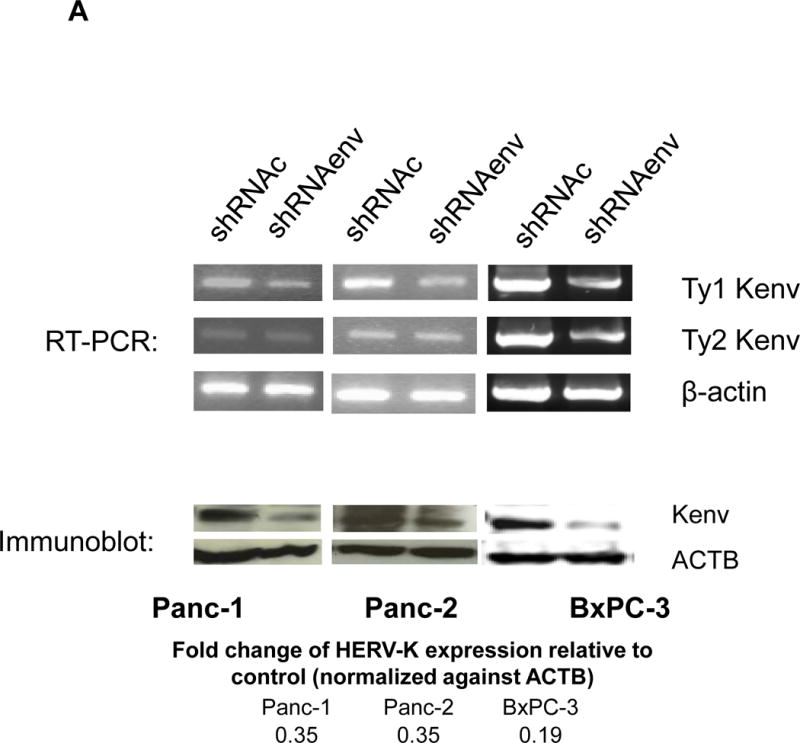

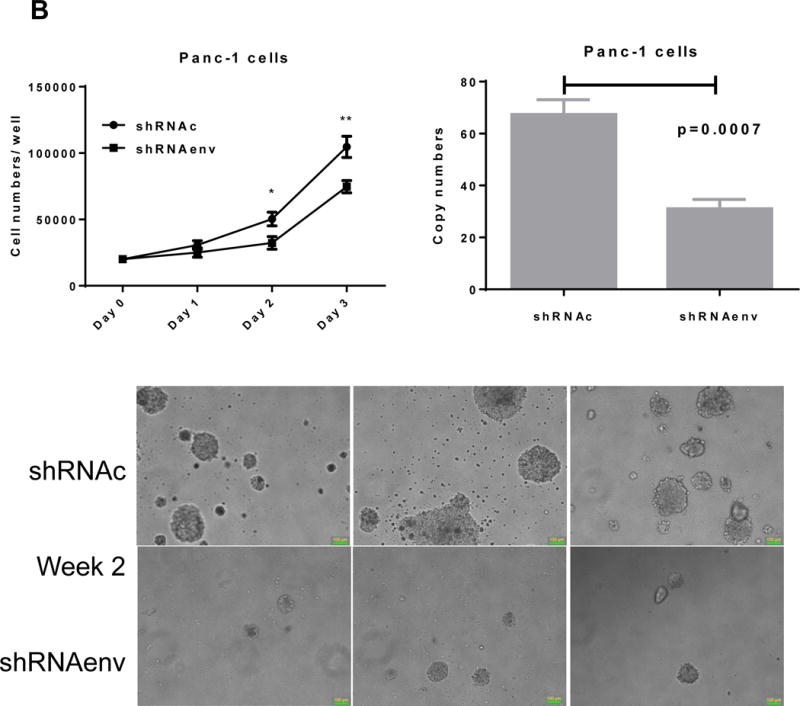

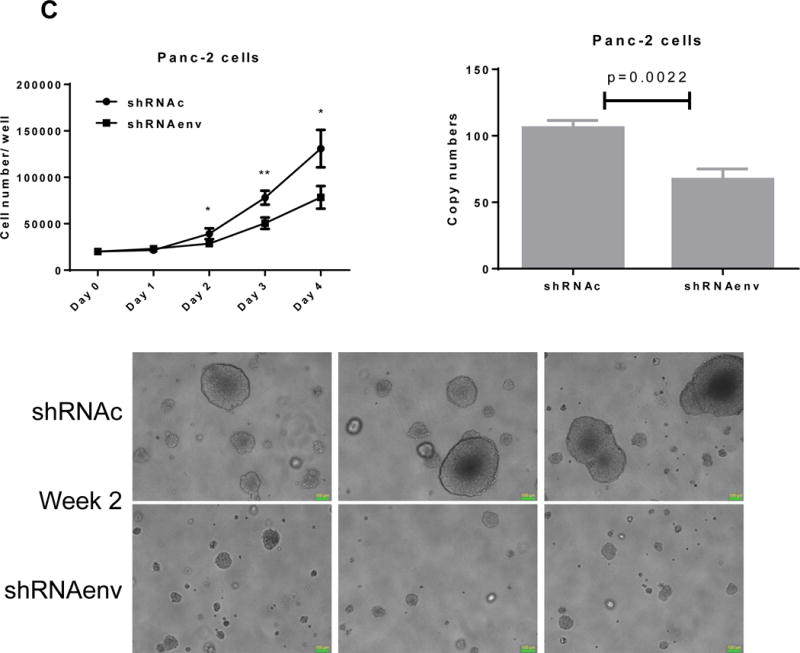

Down-regulation of expression of HERV-K env RNA or protein in PC cells by shRNA knockdown, and inhibition of pancreatic cell proliferation and transformation

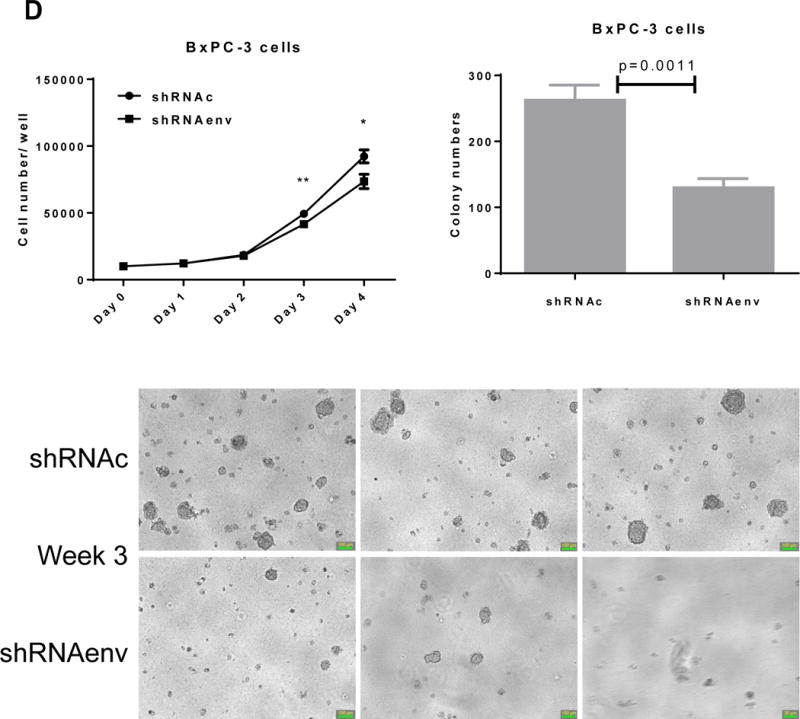

Since HERV-K expression is significantly increased in PC cell lines and patient tissue samples, we further investigated the role(s) of env RNA or protein in PC. Six small interfering RNA (siRNAs) against HERV-K env RNA and six matched scrambled controls were designed and tested. One of six siRNAs (shRNAenv) and its scrambled siRNA (shRNAc) were selected and cloned into the lentivector pGreenPuro (System Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA; sFig. 4D), which contains a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene, to generate shRNA vectors (shRNAenv) and control vector (shRNAc) as described previously (42). The pairs of shRNA targeting HERV-K that were used in breast cancer cells in this previous study were further tested in PC cells. The expression of HERV-K env RNA and protein in Panc-1, Panc-2 and BxPC-3 cells was partially down-regulated in cells transduced with shRNAenv, compared with expression in cells transduced with matched control shRNAc, as assessed by qRT-PCR, RT-PCR, or immunoblot assay (Fig. 4A). A significantly reduced expression of HERV-K env RNA was observed in Panc-1 (reduced by ~25%, P = 0.0221), Panc-2 (reduced by ~50%, P = 0.0318), and BxPC-3 (reduced by ~27%, P = 0.0046) cells transduced with shRNAenv compared with cells transduced with shRNAc. Down regulated expression of HERV-K were demonstrated in Panc-1, Panc-2, and BxPC-3 cell lines by immunoblot using anti-HERV-K monoclonal antibody (6H5). Cell proliferation and transformation were significantly decreased in the Panc-1 (Fig. 4B), Panc-2 (Fig. 4C), and BxPC-3 (Fig. 4D) cells transduced with shRNAenv compared with shRNAc. Reduced colony numbers of Panc-1 or Panc-2 cells transduced with shRNAenv were demonstrated in images of 6 well plates (sFig. 4E). The results indicate that HERV-K Env regulates PC cell proliferation and transformation. We also observed reduced pol gene expression in Panc-1 and BxPC-3 cells (sFig. 4F).

Figure 4.

Downregulation of HERV-K in PC cell lines in vitro by shRNAenv transduction. A, reduced expression of HERV-K env mRNA was demonstrated in Panc-1, Panc-2, or BxPC-3 cells transduced with HERV-K env shRNA (shRNAenv) compared with control shRNA (shRNAc). Expression was determined by qRT-PCR (P = 0.0221 for Panc-1, P = 0.0318 for Panc-2, and P = 0.0046 for BxPC-3, top panel) and confirmed by RT-PCR in both cell lines and in the BxPC-3 cell line (middle panel). Furthermore, the reduced expression of HERV-K Env at the protein level was demonstrated by immunoblot assay using 6H5 mAb (bottom panel). ACTB was used as the control. Reduced expression of HERV-K env protein was demonstrated in Panc-1 (65%), Panc-2 (65%), and BxPC-3 (81%) analysis by Image J. B–D, determination of cell proliferation and colony formation in Panc-1 (B), Panc-2 (C), and BxPC-3 cells (D) after treatment with shRNAenv or shRNAc. 10 fields were randomly chosen from each well under a microscope (10×), colonies in these fields were counted, and the sum was used as the colony number of that well. A significantly decreased proliferation rate (top left panels) and reduced transformation was observed in the three PC cell lines transduced with shRNAenv than in those transduced with shRNAc. In an anchorage-independent colony formation assay, the colony-formation potential of Panc-1, Panc-2, and BxPC-3 cells was significantly inhibited by shRNAenv (P = 0.0007, P = 0.0022 or P = 0.0011, respectively) (top right panels). Representative pictures of colonies formed from shRNAc- or shRNAenv-transduced Panc-1(week 2 post-transduction), Panc-2 (week 2 post-transduction) or BxPC-3 cells (week 3 post-transduction) are shown (bottom panels, magnification = 100×, the bar=100 μm). For statistical analysis, an unpaired two-tailed t-test was used.

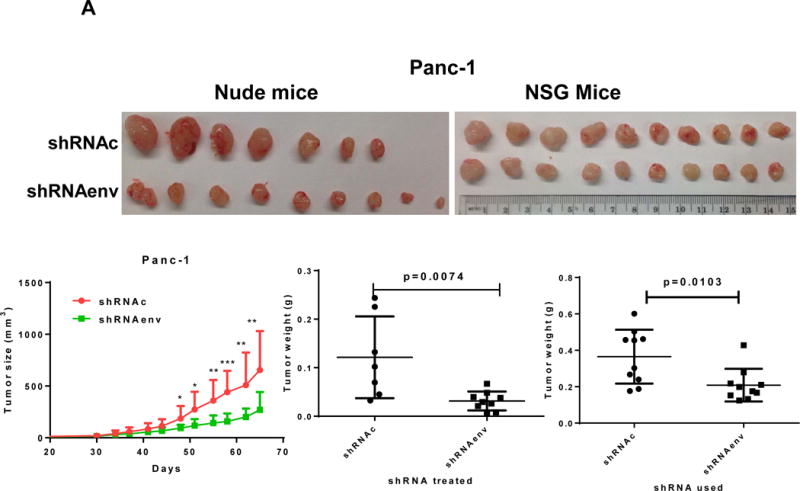

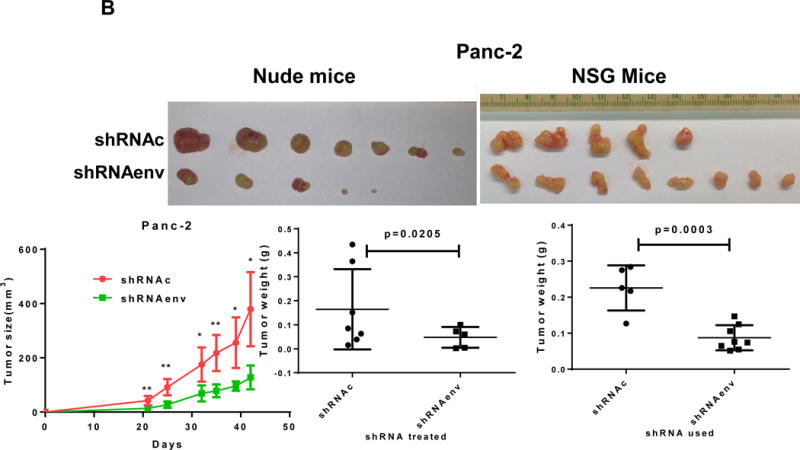

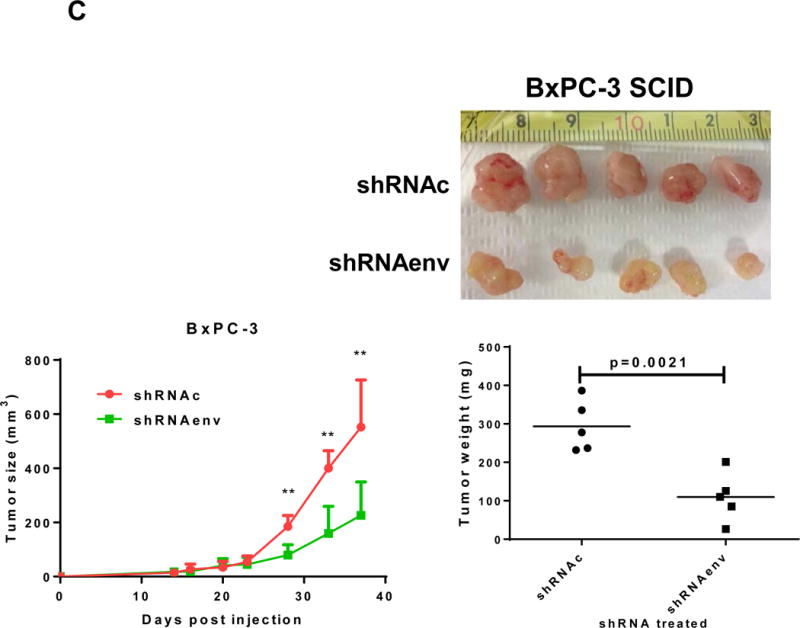

Knockdown of HERV-K Env reduced tumor growth in xenograft models

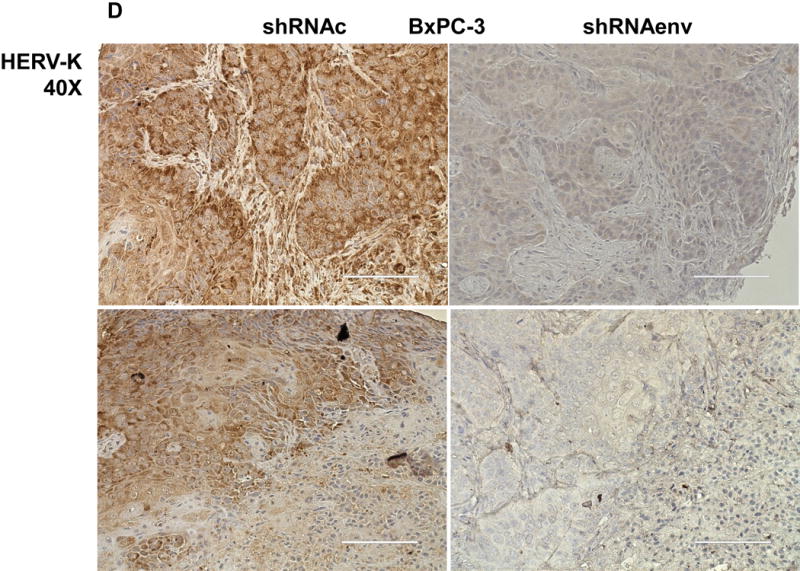

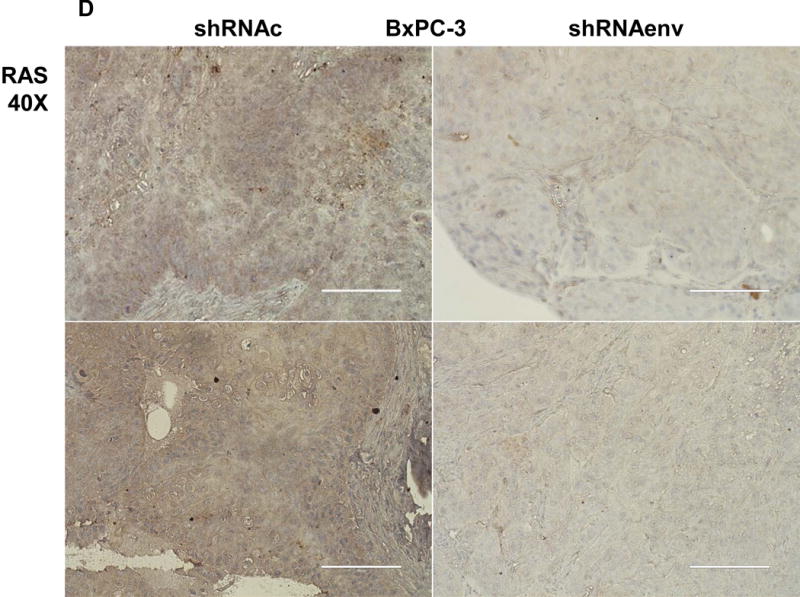

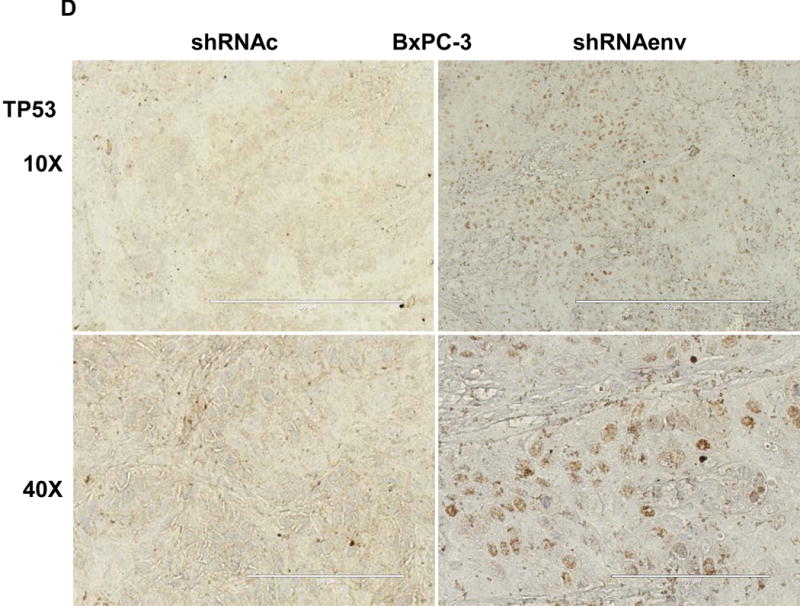

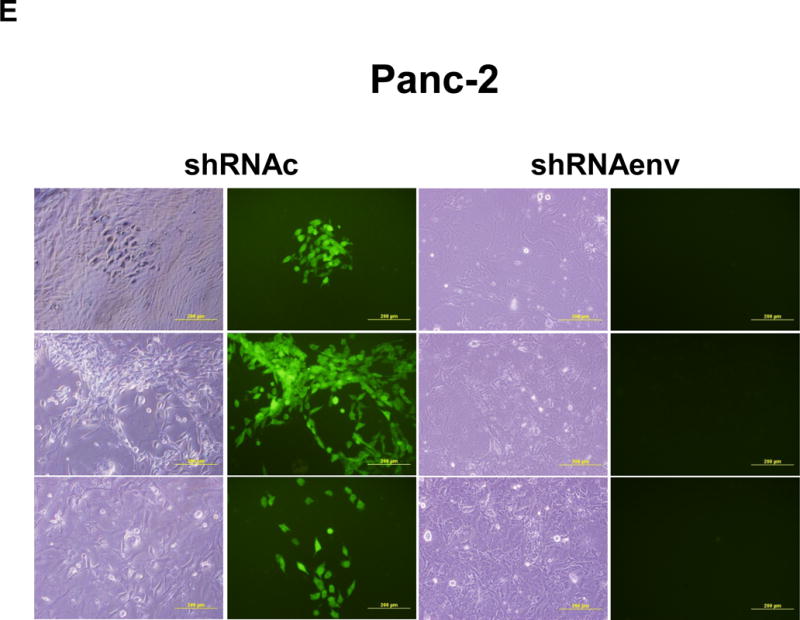

Human pancreatic tumor xenografts were generated in female immunocompromised mice by injection of Panc-1 (Fig. 5A), Panc-2 (Fig. 5B), or BxPC-3 cells (Fig. 5C) that had been transduced with shRNAenv or shRNAc expression vectors. Tumor growth was slower in PC cells transfected with shRNAenv, and tumor weights were significantly reduced in mouse xenografts inoculated with Panc-1 (Fig. 5A, p=0.0074 or p=0.0103), Panc-2 (Fig. 5B, p=0.0205 or p=0.0003), or BxPC-3 (Fig. 5C, p=0.0021) cells transduced with shRNAenv compared with shRNAc. Similar results were observed in mice inoculated with MIA PaCa-2 cells transfected with shRNAgag (sFig. 5A). Histological evaluation of biopsies of Panc-2 cell-derived tumors revealed increased necrosis in shRNAc tumor compare to in shRNAenv tumors (sFig. 5B, top panel), which may be due to the rapid growth of shRNAc tumors. Histology of BxPC-3 biopsies is shown in sFig. 5B, bottom panel. Down-regulated expression of HERV-K Env (Fig. 5D, top panel) or RAS protein (middle panel), but up-regulated TP53 (bottom panel) was observed in tumor biopsies obtained from BxPC-3 xenografts transduced with shRNAenv. In addition, down-regulation of HERV-K vRNA expression in Panc-2 (P=0.0011) (sFig. 5C) and in MIA PaCa-2 tumor biopsies (P=0.0328 for env and P=0.0038 for gag) was demonstrated by qRT-PCR, as was down-regulation of MDM2 expression in MIA PaCa-2 tumor biopsies (P=0.0227). This finding suggests a potentially important role for HERV-K Env in enabling the formation of tumors.

Figure 5.

Reduced tumor growths and metastasis in vivo after shRNAenv downregulation of HERV-K. A-C, significantly slower growth was demonstrated in three PC cell lines transfected with shRNAenv compared with shRNAc. Smaller tumor sizes (top panels), reduced grow curves (bottom left panel), and reduced tumor weights (bottom right panels) were observed when Panc-1 (A: P = 0.0074 for nude mice and P = 0.0103 for NSG mice), Panc-2 (B: P = 0.0205 for nude mice and P = 0.0003 for NSG mice), or BxPC-3 (C: P = 0.0021 for NOD/SCID mice) cells transduced with shRNAenv were compared with those transduced with shRNAc cells. D, IHC was used to determine the expression of HERV-K or RAS in BxPC-3 tumors. Reduced expression of HERV-K and RAS was demonstrated in tumors expressing shRNAenv. Increased expression of TP53 was detected in tumors expression shRNAenv. E. GFP-positive Panc-2 cells were observed in three lung biopsies of mice bearing xenografts of Panc-2 cells transduced with shRNAc) but not with shRNAenv. Pictures were taken from the bottom of the dishes where the lung biopsies had been cultured for 3 weeks. For statistical analysis, an unpaired two-tailed t-test was used.

PC cells transfected with pGreenPuro vector (sFig. 4D) exhibit GFP expression. Sections of lung tissues from these mice also shows that human GFP+ Panc-2 cells with shRNAc, but no cells with shRNAenv, had metastasized to the lung (sFig. 5D). Of interest, while there were no significant nodes of metastasis observed in the lungs of mouse xenografts, when the lungs were dissociated and cultured for 3 weeks, GFP+ Panc-2 cells were observed in the plates with lung tissues from control shRNAc mice but not shRNAenv mice (NSG mice) (Fig. 5E). No metastasis was observed in BxPC-3 xenograft models.

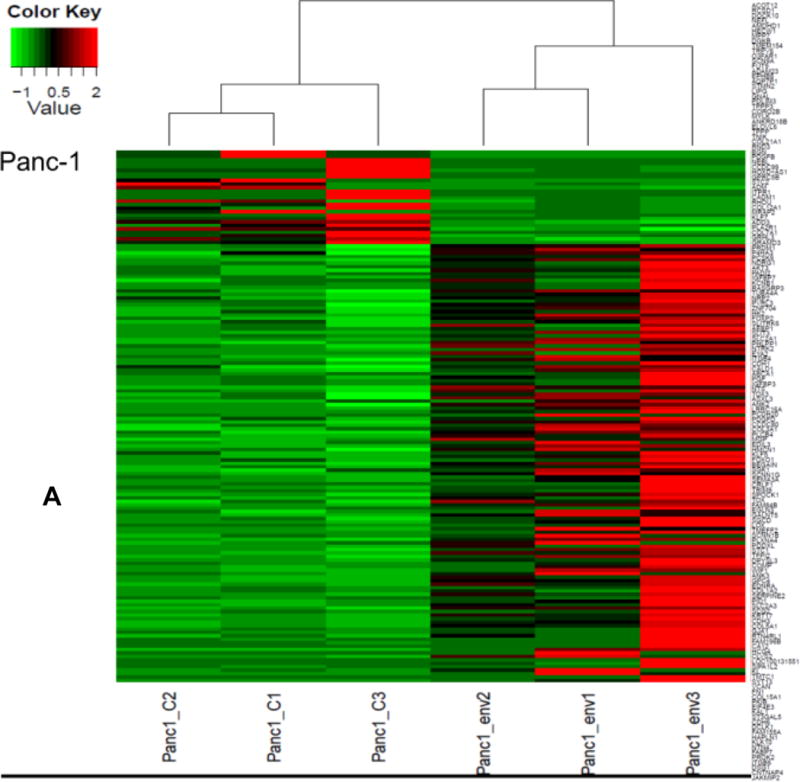

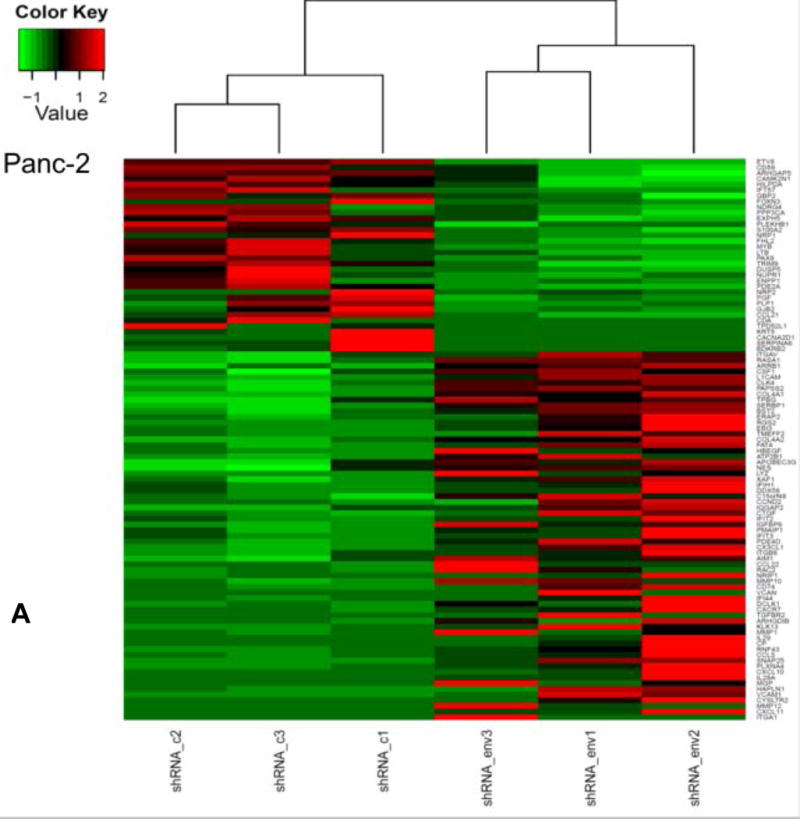

Differential gene expression profiling by RNA-Seq

We performed differential gene expression analysis of shRNAenv versus shRNAc xenografts by RNA-Seq. To account for variations among biological replicates, three tumor tissues each of shRNAenv and shRNAc xenografts were obtained from Panc-2 and Panc-1 tumors. The heatmap of gene expression changes is shown in Fig. 6A for Panc-1 (27 downregulated and 44 upregulated: top panel) and Panc-2 (78 down-regulated and 62 up-regulated: bottom panel). (up- and down-regulated genes are listed in sTable 3). Gene function and pathway analysis was performed on the differentially expressed genes in both Panc-1 (blue) and Panc-2 (red) KD cells using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software. The common Upstream Regulator genes between Panc-1 and Panc-2 were compared and analyzed using the IPA database. The “Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer” is the most enriched canonical pathway common to Panc-1 and Panc-2 cells following knockdown of HERV-K vRNA expression (sFig. 6A). Furthermore, the upstream regulators of Panc-1 and Panc-2 as well as breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231 (KRAS mutation) or MCF-7 (wild type KRAS) were comparable after knockdown of HERV-K (sTable 4), which indicates that HERV-K affects similar signaling pathways in pancreatic and breast cancers.

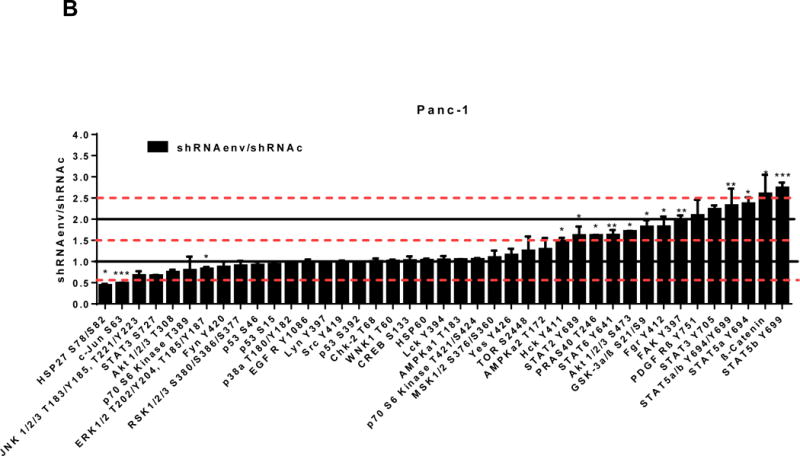

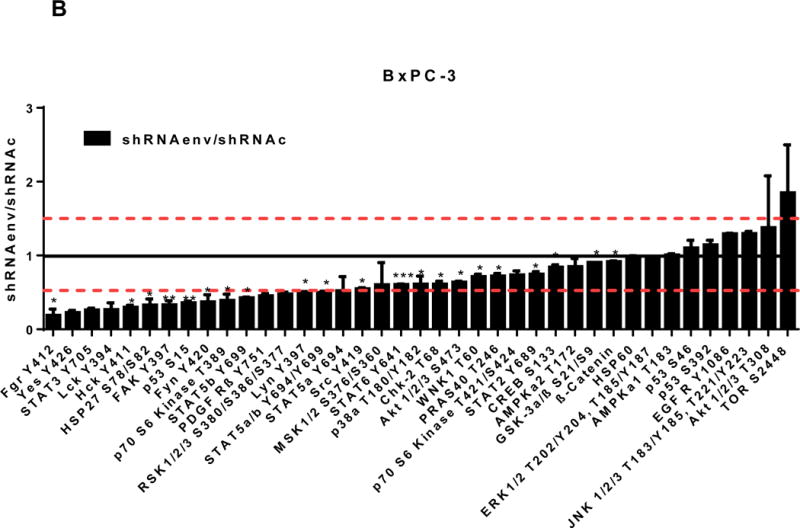

Figure 6.

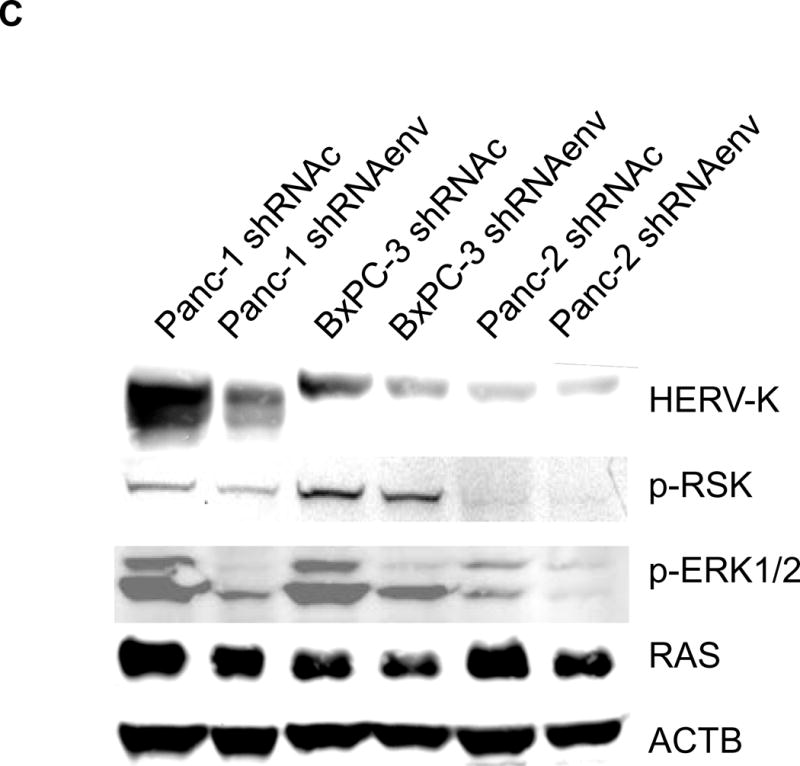

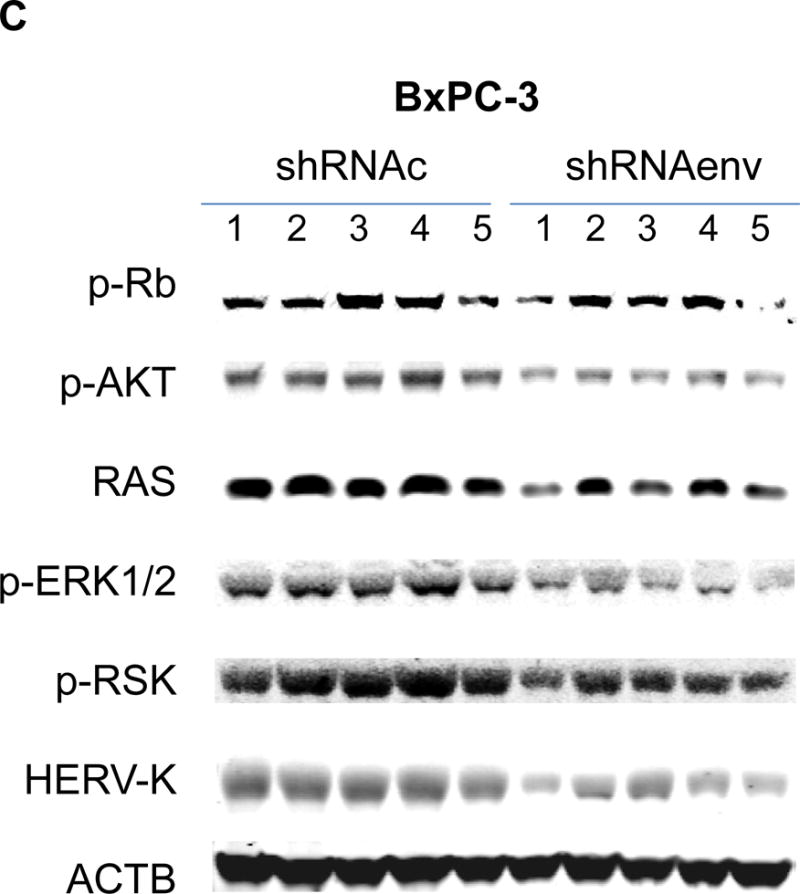

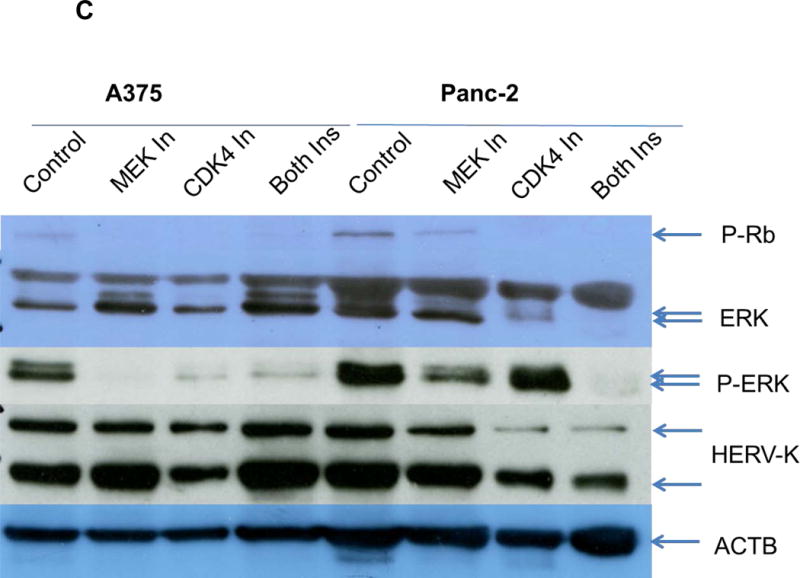

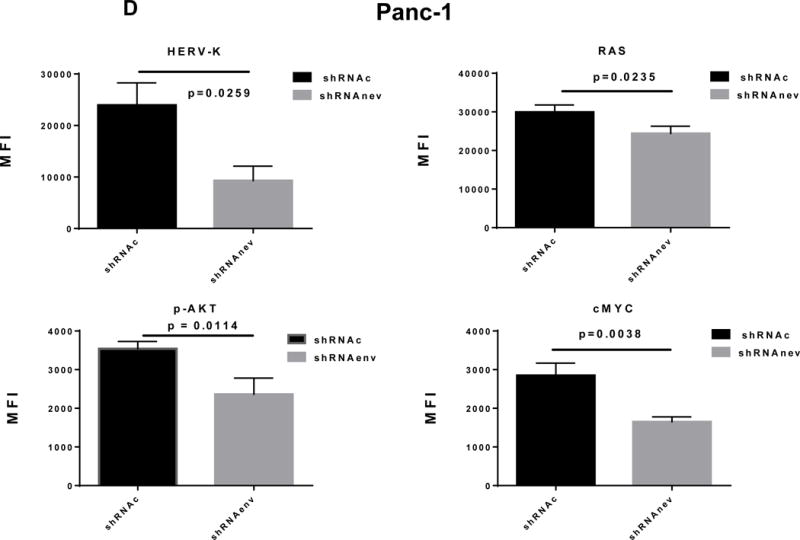

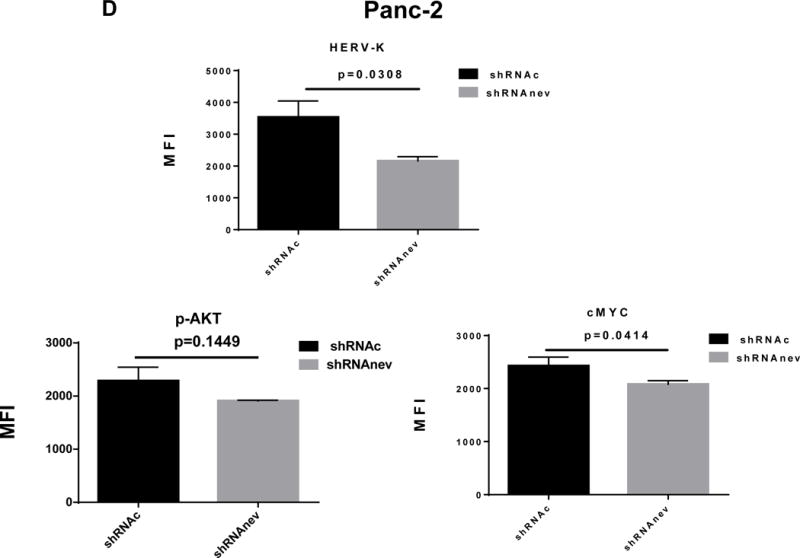

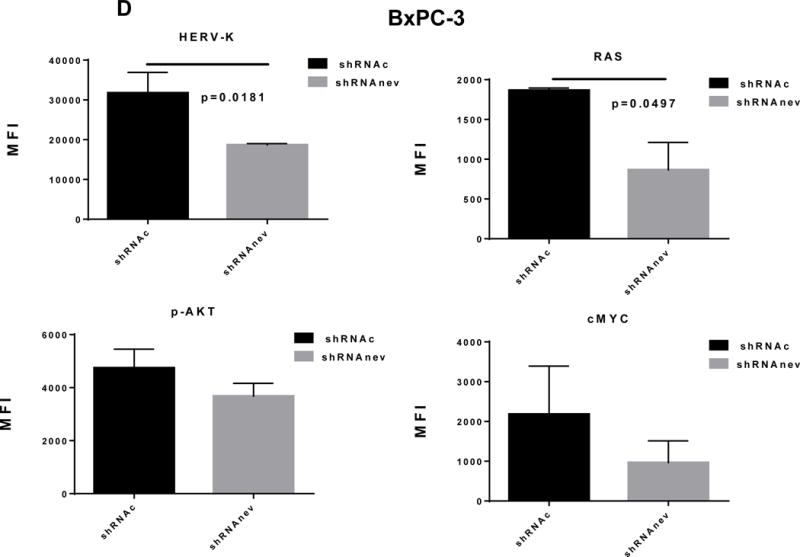

Pathway analyses of xenografts of pancreatic cancer cells transduced with shRNAenv compared with shRNAc. A, heatmap of gene expression changes of Panc-1 or Panc-2. Three individual xenograft tumors obtained from Panc-1 (top panel) or Panc-2 (bottom panel) cells transduced with shRNAenv were compared with those from cells transduced with shRNAenv. Differentially expressed genes were sorted based on the log2 ratio of expression in shRNAc to shRNAenv. B, phosphoprotein arrays were analyzed in Panc-1 (top panel) or BxPC-3 (bottom panel) cells transduced with shRNAenv or shRNAc. The fold changes of shRNAenv vs. shRNAc from both PC cell lines are shown. (***: p≤ 0.001; **: 0.001<p≤ 0.01; *:0.01<p≤ 0.05). C, immunoblot was employed to evaluate protein expression in two pairs (KD and control) of PC cells (top panel). Expression of HERV-K, p-RSK, p-ERK1/2, and RAS were compared in pairs of the three PC cell lines. Expression of p-Rb, p-AKT, RAS, p-ERK1/2, p-RSK and HERV-K Env protein is compared in tumor biopsies obtained from pairs of BxPC-3 cell xerographs by immunoblot (middle panel), and p-Rb, ERK, p-ERK and HERV-K expression was compared in melanoma cells (A375) and Panc-2 cells with and without small molecule inhibition of MEK, CDK4, or a combination of both inhibitors (bottom panel). D, expression of HERV-K (P = 0.0259), RAS (P = 0.0235), cMYC (P = 0.0038), and p-AKT (P = 0.0114) was significantly downregulated in Panc-1 cells stably-transduced with shRNAenv, as determined by flow cytometry. Similar results were detected in Panc-2 and BxPC-3 cells. For statistical analysis, an unpaired two-tailed t-test was used.

Nineteen genes were shared in both cells’ tumors when HERK-V was knocked down (sFig. 6B). These results indicate that shRNAenv treatment of Panc-1 and Panc-2 cells induced changes in gene expression and activation of pathways that are in some cases common to the two PC cell lines. Expression of genes important in pancreatic carcinogenesis would be expected to change with HERV-K downregulation. In addition, genes or regulatory factors known to be altered as a function of HERV-K expression in other cancers (see above), and that play a role in RAS signaling would also be expected to exhibit modified expression with HERV-K knockdown. For example, expression of the CCDC80 gene is decreased in PC, and its expression is downregulated by oncogenes that include KRAS and HRAS (58). Activated RAS is also known to signal through the PDK1/PI3K (PIK3CA) pathway in PC (59), and we found that HERV-K downregulation decreases RAS expression.

Networks that were activated when HERV-K was knocked down include cellular movement, cancer, cardiovascular system development and function, antimicrobial response, inflammatory response and cell to cell signaling, as well as antimicrobial response, cancer, and endocrine system disorders (sFig. 6C). The most enriched cancer pathways in Panc-1 or Panc-2 (sFig. 6D) shRNAenv tumors were analyzed using the IPA database. The major common upstream regulated molecules involved in the two PC cell lines after HERV-K KD and these regulated molecules will be investigated in greater detail in future studies, to improve our understanding of the mechanism by which HERV-K influences pancreatic tumorigenesis, and to develop new PC biomarkers.

Phosphorylation profiles of kinases in HERV-K knockdown cells

We further evaluated the association between HERV-K expression and the status of ERK pathways in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Cellular extracts prepared from Panc-1 (KRAS mutation) or BxPC-3 (wide type KRAS) cell lines transduced with shRNAenv or shRNAc were compared using phosphoprotein arrays, and results are shown in Fig. 6B. The top upregulated proteins in Panc-1 cells transduced with shRNAenv compared with shRNAc were STAT5b, β-Catenin (CTNNB1), STAT 5a, STAT 5a/b, and STAT 3 Y705; the top downregulated proteins were HSP27 (HSPB1), c-Jun (JUN), JNK 1/2/3 (MAPK8/9/10), STAT3 S727, AKT1/2/3 T308, p70 S6 Kinase, and ERK1/2. The effect of HERV-K KD on the phosphoprotein expression pattern in BxPC-3 cells differed somewhat from the pattern in Panc-1 cells. The differential expression may due to the status of KRAS mutation in the two cell lines, and this association requires further investigation.

The association between HERV-K expression and ERK pathway status in pancreatic cancer

IPA analysis mapped ERK 1/2 to the core of the cellular movement, cancer, and cardiovascular system development and function networks, acting as a hub connected to several neighboring genes that play important roles in cell migration and invasion (sFig. 6C). Thus, we evaluated the association between HERV-K expression and ERK signaling in pancreatic cancer or tumor cells, both to validate the importance of ERK 1/2 as a hub in this network and because earlier studies had associated these pathways with HERV-K expression in A375 melanoma cells (60).

In Panc-1, BxPC-3, and Panc-2 PC cells, when HERV-K Env was knocked down by shRNA, not only was the level of p-ERK1/2 [ERK1 (T202/Y204)/ERK2 (T185/Y187)] decreased, but also the levels of its upstream regulator protein RAS and its downstream target protein p-RSK (S380). Down-regulation of the above four proteins with shRNA KD is shown in immunoblots from each cell line (Fig. 6C top panel). The percentage of down-regulation of the above four proteins after shRNAenv compared to control shRNAc (set at 100%) is shown for each cell line (sFig. 6E top panel). Downregulated expression of p-Rb (S780), p-AKT (S473), RAS, p-ERK1/2 and p-RSK was demonstrated in tumor biopsies obtained from mice inoculated with BxPC-3 transfected with shRNAenv (Fig. 6C, middle panel). The relative expression changes of these proteins were compared and analyzed by Image J, which showed significantly down regulated expression of p-AKT, RAS, p_ERK1/2, p-RSK and HERV-K Env (sFig. 6E, middle panel). PC cells were treated with the MEK (MAP2K1/2) inhibitor PD98059, the CDK4 inhibitor 219476 (Calbiochem), or the solvent vehicle as described previously with some modifications (61). The addition of an MEK inhibitor downregulated p-ERK expression and mildly inhibited HERV-K expression in Panc-2 cells, while a CDK4 inhibitor more strongly inhibited HERV-K. The addition of combined MEK and CKD4 inhibitors strongly downregulated p-Rb, p-ERK and HERV-K expression (Fig. 6C, bottom panel), and the relative expression changes of these proteins were analyzed by Image J (sFig. 6E, bottom panel). This pattern of expression in response to inhibitor addition was different than in the melanoma cell line A375. Expression of HERV-K, p-AKT, cMYC, and RAS in Panc-1, Panc-2, and BxPC3 cells was downregulated after shRNAenv KD, as shown by flow cytometry (Fig. 6D). These observations indicate that HERV-K Env may function by downregulating the RAS-ERK-RSK and AKT pathways.

Discussion

Endogenous retroviruses in addition to the HERV-K(HML-2) group studied here have been reported to be upregulated in pancreatic cancer. HERV-E (17q11) was expressed in the pancreas, and although stop codons prevented the expression of intact viral particles, long open reading frames were found in the gag and pol regions (62). In another study, HERV-H was reported to be expressed in 2 of 12 PCs, with little expression in some normal tissues (63). However, HERV-H was expressed in normal pancreas tissue (64).

The current study provides strong evidence for a role of HERV-K in pancreatic carcinogenesis. This report is the first to address full-length HERV-K and ERV3 env activation at the transcriptional level, and full-length HERV-K env activation at the translational level, in PC cells. Interestingly, a new splice variant of the env gene was detected in several PC cells, and this variant seems unique to PC, since it was not expressed in other cancer cell lines. The variant may have an oncogenic function in PC similar to other HERV-K accessory proteins such as NP9 or Rec, which are putative oncogenes. Sequences of HERV-K env genes indicated the presence of stop codons in the early region of the HERV-K gene amplified from mRNA of HPDE-E6E7 pancreatic ductal epithelial cell, but not in most of the PC cell lines; the presence of stop codons may have contributed to the lack of HERV-K protein expression in this nonmalignant cell line.

Our study also found markedly higher HERV-K Env protein expression in 7 PC cell lines and PC tissues (80% positive staining by IHC with anti-HERV-K 6H5 mAb) than in 2 non-malignant pancreatic cell lines and adjacent uninvolved pancreatic tissues from the same patients. The percentage of tumor cells expressing HERV-K increased with stages of disease, and expression was increased on the plasma membrane of PC cells, indicating that HERV-K Env could be a potential target for immunotherapy, similar to what we found in breast cancer (23,39). RT activities were increased in the culture media of most of the PC cell lines we studied, compared with nonmalignant HPDE-E6E7 cells. Viral-like particles with elevated RT activities were also found to be released from Panc-2 or Panc-1 cell lines, a finding similar to that reported by another group in lymphoma and breast cancer (22), suggesting the potential for activation of the HERV-K virus in PC. Other tumor types, such as primary and metastatic melanoma cell lines have also been found to express HERV-K viral RT (46,65), and HERV-K RT was increased in tumor tissues of breast cancer patients or ovarian cancer patients, correlating with poor prognosis and decreased overall survival (19,66). Furthermore, the higher titers of antibodies against the viral proteins HERV-K Env and NP9 observed in PC patients than in controls, and higher vRNA levels including HERV-K env and gag in the sera of PC patients than in the sera of normal donors suggests that an ongoing adaptive immune response is generated against HERV-K in PC patients. The level of these viral markers increased with disease stages, suggesting a potential value of HERV-K antibodies and vRNA as tumor biomarkers for PC. The presence of autoantibodies against HERV-K in PC is also significant from the perspective of self-tolerance mechanisms in the immune system. In previous work, we have shown that HERV-K can elicit a cellular immune response, with elevated levels of HERV-K HLA class I-restricted CD8+ T cells found circulating in breast cancer and ovarian cancer patients (23). These and our results here suggest that HERV-K could be a target for novel CD8+ and antibody-based therapies for PC.

We also found that HERV-K plays a role in regulating PC cell proliferation and maintenance of anchorage-independent growth, as shown by shRNA-based knockdown of HERV-K expression in Panc-1, Panc-2, and BxPC-3 cells in vitro, as well as promotion of PC tumor growth in vivo using xenograft approaches. We did observe that shRNAenv appears to be more effective in Panc-1 nude mouse models than in Panc-1 NSG models, while the opposite was observed in Panc-2 nude and Panc-2 NSG. While we have not addressed this phenomenon yet, there is a high likelihood that these opposite effects represent impairments of immune response or differences in immune response in the two cell lines, especially since the expression of HERV-K differs between Panc-1 and Panc-2 cells.

Of great interest, metastasis of PC cells to lung tissues in Panc-2 xenografted mice was nearly eliminated in mice harboring cells transduced with shRNAenv. The finding that the HERV-K Env level is related to lung metastasis in PC can be supported by two studies: our previous report showed that the HERV-K Env level is positively associated with metastasis in human breast cancer (2,40), and a recent report that further demonstrated that HERV-K Env vaccination in mice decreased metastasis of cancer cells (67). This finding is highly relevant for PC, where symptoms are usually not evident at early stages, and locally advanced or metastatic disease may already be present at the time of diagnosis.

Our finding of a link between HERV-K expression and the activation of the RAS-ERK-RSK pathway suggests some form of regulation whereby HERV-K accentuates these driving forces on cell division and transformation, thus making these tumors more aggressive. Mutationally activated KRAS is present in >90% of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (68), indicating the importance of RAS in PC, and suggesting that our finding in Panc-1 cells may apply to a larger portion of PC cases, and could thus provide new therapeutic targets for PC.

Our gene expression analysis of control and HERV-K shRNA-treated PC cell lines supports the hypothesis that HERV-K contributes to or facilitates maintenance of the transformed phenotype and promotes metastasis, with genes involved in cellular movement, cancer, and cellular growth and proliferation being key pathways reduced in HERV-K knock-down cells. The 20 most enriched cancer pathways in Panc-1 or Panc-2 shRNAenv tumors were those related to cancer, epithelial neoplasia and metastasis, which are pathways expected to be altered in response to KD of a gene relevant to PC.

Gene ontology, pathway enrichment and protein-protein path length analysis were all carried out to validate the biological context of the predicted network of interacting cancer genes described above. Since the RNA-Seq results suggested that signaling pathways involving phosphorylation might play prominent roles in response to HERV-K KD, phosphoprotein arrays were employed to evaluate changes in concentrations of phosphorylated proteins in Panc-1 (KRAS mutation) and BxPC-3 (wide type KRAS) cells transduced with shRNAenv compared with shRNAc. However, the results in Panc-1 cells did not totally match those in BxPC-3 cells, which may due to the presence of wild type KRAS in BxPC-3 cells.

Downregulated HSP27 was observed in both PC cell lines when HERV-K was knocked down. HSP27 expression was found in 49% of tumor samples and a significant correlation was found between HSP27 expression and survival (69). Furthermore, HSP27 expression correlated inversely with nuclear TP53 accumulation in pancreatic cancer, and upregulated expression of TP53 (p-S46) or TP53 (p-S392) was observed in BxPC-3 after KD of HERV-K.

Downregulated expression of p70S6 kinase (RPS6KB1) (p-T389) was demonstrated in both PC cell lines after KD of HERV-K, which indicates that HERV-K may promote its activation and cause PC cell proliferation. TGFβ1 (TGFB1) is a strong upstream regulator involved in HERV-K mediated signal transduction (sTable 4), and TGFβ1 promoted the growth of K-RAS-driven PC cells lacking RB and additionally enhanced p70 S6 kinase T389 phosphorylation (70). Downregulated expression of ERK1/2 in Panc-2 cells, and of RSK1/2/3 in BxPC-3 PC cell lines was observed.

Downregulated expression of c-Jun and JNK1/2/3 in Panc-1 cells was demonstrated after KD of HERV-K. c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) is a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, and it is reportedly involved in the development of several cancers, especially PC (71). JNK was frequently activated in human and murine pancreatic cancer in vitro and in vivo. KRAS expression led to activation of JNK in pancreatic cancer cell lines (71). HERV-K control of RAS expression has been reported by us in breast cancer (41,42), and our results in the current study using KRAS mutant Panc-1 cells suggest that HERV-K may induce JNK activation in PCs with KRAS mutation.

Furthermore, immunoblot analysis revealed downregulation of expression of RAS, p-ERK1/2, and p-RSK in Panc-1 cell lines after KD of HERV-K expression. These observations from in vitro studies were verified in tumor biopsies, which showed downregulation of p-RB, p-AKT, RAS, p- ERK1/2, and p-RSK after HERV-K KD.

In summary, we report that the endogenous retrovirus HERV-K is overexpressed in PC and the effects of KD of the HERV-K vRNA suggest that HERV-K Env protein plays an integral role in PC proliferation and tumorigenesis, as well metastasis formation. HERV-K may not only regulate KRAS through hyperactivation of the RAS/MEK/ERK pathway in PC, but may also stimulate PC proliferation by upregulation of p70S6 Kinase/JNK/C-Jun signaling. Future studies based on our results reported here could pave the way for immunotherapy regimens in PC clinical trials, as well as a deeper molecular understanding of how endogenous retroviral gene reactivation drives oncogene activation and subsequent cellular transformation and tumor cell proliferation.

Supplementary Material

Statement of translational relevance.

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is frequently not detected in its early stages and it spreads rapidly. These factors are leading contributors to PC death. We report that an ancient endogenous retrovirus, HERV-K, which has integrated into the human genome, can be targeted to prevent PC cell proliferation, as well as tumor growth and metastasis in xenograft models. Reverse transcriptase (RT) activity and HERV-K mRNA in PC cells and patient sera, and the presence of endogenous retrovirus-like particles in PC cell supernatants suggest that an active retrovirus may contribute to the pathology of this cancer. We also report a new splice variant of HERV-K that seems unique to PC, since we have not observed its presence in other cancers. Knockdown of HERV-K Env protein expression by shRNA downregulated the RAS-ERK-RSK signaling pathway, which is important in PC progression. Our findings establish a novel endogenous retroviral biomarker and target for therapy of PC.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant W81XWH-15-1-0530 and W81XWH-12-1-0223 from the United States Department of Defense, grant BCTR0402892 from Susan G. Komen for the Cure, and grants 07-2007-070 01 (GLJ) and 02-2011-104 (FWJ) from the Avon Foundation for Women. We thank Albert Lee for immunohistochemistry data used in Fig. 5D and Nishan Gajjar for producing the data used in Fig. 6C. We thank Dr. Peisha Yan (Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston) for pathology reports. We thank Dr. James L Abbruzzese for providing his patient sample collection for the studies described here. We also thank the Cattlemen for Cancer Research for providing us with seed money for this work (F.W-J., G.L.J.). The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through core grant CA16672 and by CPRIT grant RP120348 (J.J.S.). The JLA-20 antibody was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA 52242. This research was performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ph.D. or M.S. degree from The University of Texas Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at Houston; The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas 77030.

Financial support: F. Wang-Johanning, United States Department of Defense, grant numbers W81XWH-15-1-0530 and W81XWH-12-1-0223; F. Wang-Johanning, Susan G. Komen for the Cure, grant number BCTR0402892; F. Wang-Johanning, Avon Breast Cancer Crusade, grant number 02-2011-104; G.L. Johanning, Avon Breast Cancer Crusade, grant number 07-2007-070 01; F. Wang-Johanning and G. L. Johanning, Cattlemen for Cancer Research, pilot project; JianJun Shen, National Institutes of Health, grant number CA16672; JianJun Shen, Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, grant number RP120348.

Footnotes

Suppression of Cancer Progression by HERV-K Knockdown

References

- 1.Antony JM, Deslauriers AM, Bhat RK, Ellestad KK, Power C. Human endogenous retroviruses and multiple sclerosis: innocent bystanders or disease determinants? Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2011;1812(2):162–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang-Johanning F, Li M, Esteva FJ, Hess KR, Yin B, Rycaj K, et al. Human endogenous retrovirus type K antibodies and mRNA as serum biomarkers of early-stage breast cancer. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2014;134(3):587–95. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassiotis G. Endogenous retroviruses and the development of cancer. J Immunol. 2014;192(4):1343–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhardwaj N, Coffin JM. Endogenous retroviruses and human cancer: is there anything to the rumors? Cell host & microbe. 2014;15(3):255–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reis BS, Jungbluth AA, Frosina D, Holz M, Ritter E, Nakayama E, et al. Prostate cancer progression correlates with increased humoral immune response to a human endogenous retrovirus GAG protein. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19(22):6112–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahyo T, Tao H, Shinmura K, Yamada H, Mori H, Funai K, et al. Identification and association study with lung cancer for novel insertion polymorphisms of human endogenous retrovirus. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(11):2531–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherkasova E, Weisman Q, Childs RW. Endogenous Retroviruses as Targets for Antitumor Immunity in Renal Cell Cancer and Other Tumors. Frontiers in oncology. 2013;3:243. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cegolon L, Salata C, Weiderpass E, Vineis P, Palu G, Mastrangelo G. Human endogenous retroviruses and cancer prevention: evidence and prospects. BMC cancer. 2013;13:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullins CS, Linnebacher M. Human endogenous retroviruses and cancer: causality and therapeutic possibilities. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2012;18(42):6027–35. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okuma Y, Yanagisawa N, Takagi Y, Hosomi Y, Suganuma A, Imamura A, et al. Clinical characteristics of Japanese lung cancer patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. International journal of clinical oncology. 2012;17(5):462–9. doi: 10.1007/s10147-011-0316-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stengel S, Fiebig U, Kurth R, Denner J. Regulation of human endogenous retrovirus-K expression in melanomas by CpG methylation. Genes, chromosomes & cancer. 2010;49(5):401–11. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flockerzi A, Ruggieri A, Frank O, Sauter M, Maldener E, Kopper B, et al. Expression patterns of transcribed human endogenous retrovirus HERV-K(HML-2) loci in human tissues and the need for a HERV Transcriptome Project. BMC genomics. 2008;9:354. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romanish MT, Cohen CJ, Mager DL. Potential mechanisms of endogenous retroviral-mediated genomic instability in human cancer. Seminars in cancer biology. 2010;20(4):246–53. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serafino A, Balestrieri E, Pierimarchi P, Matteucci C, Moroni G, Oricchio E, et al. The activation of human endogenous retrovirus K (HERV-K) is implicated in melanoma cell malignant transformation. Experimental cell research. 2009;315(5):849–62. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt KL, Vangsted AJ, Hansen B, Vogel UB, Hermansen NE, Jensen SB, et al. Synergy of two human endogenous retroviruses in multiple myeloma. Leukemia research. 2015;39(10):1125–8. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhyu DW, Kang YJ, Ock MS, Eo JW, Choi YH, Kim WJ, et al. Expression of human endogenous retrovirus env genes in the blood of breast cancer patients. International journal of molecular sciences. 2014;15(6):9173–83. doi: 10.3390/ijms15069173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oricchio E, Sciamanna I, Beraldi R, Tolstonog GV, Schumann GG, Spadafora C. Distinct roles for LINE-1 and HERV-K retroelements in cell proliferation, differentiation and tumor progression. Oncogene. 2007;26(29):4226–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma W, Hong Z, Liu H, Chen X, Ding L, Liu Z, et al. Human Endogenous Retroviruses-K (HML-2) Expression Is Correlated with Prognosis and Progress of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. BioMed research international. 2016;2016:8201642. doi: 10.1155/2016/8201642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golan M, Hizi A, Resau JH, Yaal-Hahoshen N, Reichman H, Keydar I, et al. Human endogenous retrovirus (HERV-K) reverse transcriptase as a breast cancer prognostic marker. Neoplasia. 2008;10(6):521–33. doi: 10.1593/neo.07986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goering W, Schmitt K, Dostert M, Schaal H, Deenen R, Mayer J, et al. Human endogenous retrovirus HERV-K(HML-2) activity in prostate cancer is dominated by a few loci. The Prostate. 2015;75(16):1958–71. doi: 10.1002/pros.23095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer S, Echeverria N, Moratorio G, Landoni AI, Dighiero G, Cristina J, et al. Human endogenous retrovirus np9 gene is over expressed in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Leukemia research reports. 2014;3(2):70–2. doi: 10.1016/j.lrr.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Contreras-Galindo R, Kaplan MH, Leissner P, Verjat T, Ferlenghi I, Bagnoli F, et al. Human endogenous retrovirus K (HML-2) elements in the plasma of people with lymphoma and breast cancer. Journal of virology. 2008;82(19):9329–36. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00646-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang-Johanning F, Radvanyi L, Rycaj K, Plummer JB, Yan P, Sastry KJ, et al. Human endogenous retrovirus K triggers an antigen-specific immune response in breast cancer patients. Cancer research. 2008;68(14):5869–77. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang-Johanning F, Liu J, Rycaj K, Huang M, Tsai K, Rosen DG, et al. Expression of multiple human endogenous retrovirus surface envelope proteins in ovarian cancer. International journal of cancer. 2007;120(1):81–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menendez L, Benigno BB, McDonald JF. L1 and HERV-W retrotransposons are hypomethylated in human ovarian carcinomas. Molecular cancer. 2004;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maliniemi P, Vincendeau M, Mayer J, Frank O, Hahtola S, Karenko L, et al. Expression of human endogenous retrovirus-w including syncytin-1 in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. PloS one. 2013;8(10):e76281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross H, Barth S, Pfuhl T, Willnecker V, Spurk A, Gurtsevitch V, et al. The NP9 protein encoded by the human endogenous retrovirus HERV-K(HML-2) negatively regulates gene activation of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2) International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2011;129(5):1105–15. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitt K, Reichrath J, Roesch A, Meese E, Mayer J. Transcriptional profiling of human endogenous retrovirus group HERV-K(HML-2) loci in melanoma. Genome biology and evolution. 2013;5(2):307–28. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh S, Kaye S, Francis N, Peston D, Gore M, McClure M, et al. Human endogenous retrovirus K (HERV-K) rec mRNA is expressed in primary melanoma but not in benign naevi or normal skin. Pigment cell & melanoma research. 2013;26(3):426–8. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katoh I, Mirova A, Kurata S, Murakami Y, Horikawa K, Nakakuki N, et al. Activation of the long terminal repeat of human endogenous retrovirus K by melanoma-specific transcription factor MITF-M. Neoplasia. 2011;13(11):1081–92. doi: 10.1593/neo.11794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schanab O, Humer J, Gleiss A, Mikula M, Sturlan S, Grunt S, et al. Expression of human endogenous retrovirus K is stimulated by ultraviolet radiation in melanoma. Pigment cell & melanoma research. 2011;24(4):656–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reiche J, Pauli G, Ellerbrok H. Differential expression of human endogenous retrovirus K transcripts in primary human melanocytes and melanoma cell lines after UV irradiation. Melanoma research. 2010;20(5):435–40. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32833c1b5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morozov VA, Dao Thi VL, Denner J. The transmembrane protein of the human endogenous retrovirus–K (HERV-K) modulates cytokine release and gene expression. PloS one. 2013;8(8):e70399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraus B, Monk B, Sliva K, Schnierle BS. Expression of human endogenous retrovirus-K coincides with that of micro-RNA-663 and -638 in germ-cell tumor cells. Anticancer research. 2012;32(11):4797–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heslin DJ, Murcia P, Arnaud F, Van Doorslaer K, Palmarini M, Lenz J. A single amino acid substitution in a segment of the CA protein within Gag that has similarity to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 blocks infectivity of a human endogenous retrovirus K provirus in the human genome. Journal of virology. 2009;83(2):1105–14. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01439-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agoni L, Lenz J, Guha C. Variant Splicing and Influence of Ionizing Radiation on Human Endogenous Retrovirus K (HERV-K) Transcripts in Cancer Cell Lines. PloS one. 2013;8(10):e76472. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang-Johanning F, Frost AR, Johanning GL, Khazaeli MB, LoBuglio AF, Shaw DR, et al. Expression of human endogenous retrovirus k envelope transcripts in human breast cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2001;7(6):1553–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang-Johanning F, Frost AR, Jian B, Epp L, Lu DW, Johanning GL. Quantitation of HERV-K env gene expression and splicing in human breast cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22(10):1528–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang-Johanning F, Rycaj K, Plummer JB, Li M, Yin B, Frerich K, et al. Immunotherapeutic potential of anti-human endogenous retrovirus-K envelope protein antibodies in targeting breast tumors. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012;104(3):189–210. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao J, Rycaj K, Geng S, Li M, Plummer JB, Yin B, et al. Expression of Human Endogenous Retrovirus Type K Envelope Protein is a Novel Candidate Prognostic Marker for Human Breast Cancer. Genes & cancer. 2011;2(9):914–22. doi: 10.1177/1947601911431841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou F, Krishnamurthy J, Wei Y, Li M, Hunt K, Johanning GL, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells targeting HERV-K inhibit breast cancer and its metastasis through downregulation of Ras. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4(11):e1047582. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1047582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou F, Li M, Wei Y, Lin K, Lu Y, Shen J, et al. Activation of HERV-K Env protein is essential for tumorigenesis and metastasis of breast cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Getz G, Hacohen N. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell. 2015;160(1–2):48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kurth R, Bannert N. Beneficial and detrimental effects of human endogenous retroviruses. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(2):306–14. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moyes D, Griffiths DJ, Venables PJ. Insertional polymorphisms: a new lease of life for endogenous retroviruses in human disease. Trends Genet. 2007;23(7):326–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.05.004. doi S0168-9525(07)00175-8 [pii] 10.1016/j.tig.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muster T, Waltenberger A, Grassauer A, Hirschl S, Caucig P, Romirer I, et al. An endogenous retrovirus derived from human melanoma cells. Cancer research. 2003;63(24):8735–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;371(11):1039–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Royal RE, Levy C, Turner K, Mathur A, Hughes M, Kammula US, et al. Phase 2 trial of single agent Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) for locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Immunother. 2010;33(8):828–33. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181eec14c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366(26):2455–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmitz-Winnenthal FH, Galindo-Escobedo LV, Rimoldi D, Geng W, Romero P, Koch M, et al. Potential target antigens for immunotherapy in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2007;252(2):290–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.01.003. S0304-3835(07)00014-6 [pii] 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hohn O, Hanke K, Bannert N. HERV-K(HML-2), the Best Preserved Family of HERVs: Endogenization, Expression, and Implications in Health and Disease. Frontiers in oncology. 2013;3:246. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y, Feurino LW, Zhai Q, Wang H, Fisher WE, Chen C, et al. Thymosin Beta 4 is overexpressed in human pancreatic cancer cells and stimulates proinflammatory cytokine secretion and JNK activation. Cancer biology & therapy. 2008;7(3):419–23. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.3.5415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Karamitros T, Paraskevis D, Hatzakis A, Psichogiou M, Elefsiniotis I, Hurst T, et al. A contaminant-free assessment of Endogenous Retroviral RNA in human plasma. Scientific reports. 2016;6:33598. doi: 10.1038/srep33598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andrews CD, Spreen WR, Mohri H, Moss L, Ford S, Gettie A, et al. Long-acting integrase inhibitor protects macaques from intrarectal simian/human immunodeficiency virus. Science. 2014;343(6175):1151–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1248707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang-Johanning F, Gillespie GY, Grim J, Rancourt C, Alvarez RD, Siegal GP, et al. Intracellular expression of a single-chain antibody directed against human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein achieves targeted antineoplastic effects. Cancer research. 1998;58(9):1893–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ben El Kadhi K, Roubinet C, Solinet S, Emery G, Carreno S. The inositol 5-phosphatase dOCRL controls PI(4,5)P2 homeostasis and is necessary for cytokinesis. Curr Biol. 2011;21(12):1074–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.030. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.030 S0960-9822(11)00557-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bommer GT, Jager C, Durr EM, Baehs S, Eichhorst ST, Brabletz T, et al. DRO1, a gene down-regulated by oncogenes, mediates growth inhibition in colon and pancreatic cancer cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280(9):7962–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412593200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eser S, Reiff N, Messer M, Seidler B, Gottschalk K, Dobler M, et al. Selective requirement of PI3K/PDK1 signaling for Kras oncogene-driven pancreatic cell plasticity and cancer. Cancer cell. 2013;23(3):406–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li Z, Sheng T, Wan X, Liu T, Wu H, Dong J. Expression of HERV-K correlates with status of MEK-ERK and p16INK4A-CDK4 pathways in melanoma cells. Cancer investigation. 2010;28(10):1031–7. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2010.512604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stengel S, Fiebig U, Kurth R, Denner J. Regulation of human endogenous retrovirus-K expression in melanomas by CpG methylation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 49(5):401–11. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shiroma T, Sugimoto J, Oda T, Jinno Y, Kanaya F. Search for active endogenous retroviruses: identification and characterization of a HERV-E gene that is expressed in the pancreas and thyroid. Journal of human genetics. 2001;46(11):619–25. doi: 10.1007/s100380170012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wentzensen N, Coy JF, Knaebel HP, Linnebacher M, Wilz B, Gebert J, et al. Expression of an endogenous retroviral sequence from the HERV-H group in gastrointestinal cancers. International journal of cancer. 2007;121(7):1417–23. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kudo-Saito C, Yura M, Yamamoto R, Kawakami Y. Induction of immunoregulatory CD271+ cells by metastatic tumor cells that express human endogenous retrovirus H. Cancer research. 2014;74(5):1361–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buscher K, Trefzer U, Hofmann M, Sterry W, Kurth R, Denner J. Expression of human endogenous retrovirus K in melanomas and melanoma cell lines. Cancer research. 2005;65(10):4172–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rycaj K, Plummer JB, Yin B, Li M, Garza J, Radvanyi L, et al. Cytotoxicity of human endogenous retrovirus K-specific T cells toward autologous ovarian cancer cells. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2015;21(2):471–83. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kraus B, Fischer K, Buchner SM, Wels WS, Lower R, Sliva K, et al. Vaccination directed against the human endogenous retrovirus-K envelope protein inhibits tumor growth in a murine model system. PloS one. 2013;8(8):e72756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eser S, Schnieke A, Schneider G, Saur D. Oncogenic KRAS signalling in pancreatic cancer. British journal of cancer. 2014;111(5):817–22. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schafer C, Seeliger H, Bader DC, Assmann G, Buchner D, Guo Y, et al. Heat shock protein 27 as a prognostic and predictive biomarker in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2012;16(8):1776–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gore AJ, Deitz SL, Palam LR, Craven KE, Korc M. Pancreatic cancer-associated retinoblastoma 1 dysfunction enables TGF-beta to promote proliferation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124(1):338–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI71526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takahashi R, Hirata Y, Sakitani K, Nakata W, Kinoshita H, Hayakawa Y, et al. Therapeutic effect of c-Jun N-terminal kinase inhibition on pancreatic cancer. Cancer science. 2013;104(3):337–44. doi: 10.1111/cas.12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.